Early sexual experiences of adolescent men who have sex with men

Chen Wang A B * , Christopher K. Fairley

A B * , Christopher K. Fairley  A B C , Rebecca Wigan A B , Suzanne M. Garland D E F , Catriona S. Bradshaw A B C , Marcus Y. Chen A B § and Eric P. F. Chow

A B C , Rebecca Wigan A B , Suzanne M. Garland D E F , Catriona S. Bradshaw A B C , Marcus Y. Chen A B § and Eric P. F. Chow  A B C §

A B C §

A

B

C

D

E

F

Handling Editor: Megan Lim

Abstract

There are limited studies examining the early experiences of adolescent men who have sex with men (MSM), and the magnitude of changes in sexual practice among adolescent MSM is unclear. Therefore, we compared the sexual practice and trajectory among adolescent men who are MSM aged 16–20 years in two cohorts, 5 years apart in Melbourne, Australia.

A total of 200 self-identified same-sex attracted men aged 16–20 years were recruited in each of HYPER1 (2010–2012) and HYPER2 (2017–2018) using similar methodology. Men completed a questionnaire about their sexual practices. Men were also asked to report the age of first sex with different sexual activities with men and women.

Compared to HYPER1, the median age at first sex with men was slightly increased in HYPER2: receiving oral sex (17.2 years in HYPER2 vs 16.5 years in HYPER1), performing oral sex (17.3 years vs 16.4 years), receptive anal sex (18 years vs 17.0 years) and insertive anal sex (18 years vs 17.3 years). Similar patterns were also observed in sexual practice with women: performing oral sex (17.0 years in HYPER2 vs 16.8 years in HYPER1), receiving oral sex (17.0 years vs 16.3 years) and vaginal sex (17.0 years vs 16.7 years).

In general, there was a small delay in first-sex activity among adolescent MSM between two cohorts 5 years apart. Most adolescent MSM started their sexual practices before the age of 18 years and have engaged in activities that are at risk of HIV and STI. Health education and promotion, including regular sexual health check-ups, are important for HIV and STI prevention and intervention in this population.

Keywords: adolescent, men who have sex with men, sexual behaviours, sexual debut, sexual practices, STI, youth.

Introduction

Young Australians are disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1–4 The Australian annual surveillance data have shown that young people aged 15–19 years accounted for 16.3% of all chlamydia notifications, 8.2% for all gonorrhoea notifications and 3.5% for all syphilis notifications in 2022.4 More importantly, the proportion of cases of syphilis notifications among youth aged 15–19 years has increased from 1.4% in 2012 to 4.5% in 2021.5 Untreated STIs can cause substantial morbidity.

Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) are also disproportionately affected by HIV and STIs.6 In 2022, the Australia Annual Surveillance Report estimated the incidence of chlamydia was 29.2 per 100 person-year, gonorrhoea was 23.9 per 100 person-year and infectious syphilis was 4.8 per 100 person-year among HIV-negative MSM.4 Adolescent MSM have become an emerging population that is at risk of HIV and other STIs due to early sexual debut. Sexual initiation at a younger age is associated with increased STI risk and subsequent risk behaviours later in life, including more sexual partners, higher risk-taking behaviours, a more negative attitude toward condom use, as well as unintended adolescent pregnancy.7–14 A longitudinal study among 808 fifth graders (usually aged 10–11 years) in the United States with follow-up at ages 18 years, 21 years, and 24 years found that the STI rate was 32.5% for early initiators of sex (debut at <15 years) compared to 16.6% for later initiators (debut at >15 years).15 It has been found that early sexual initiation is one of the most robust predictors of STI among adolescents and young adults in general, not just adolescent MSM.16–18

Repeated cross-sectional surveys have demonstrated changes in sexual practices over time. For example, the National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health found the proportion of Year 12 students (usually aged 17–18 years) who had experienced vaginal or anal sex has increased from 50.5% in 2013 to 68.9% in 2021.19 Furthermore, the Australian Study of Health and Relationships Surveys have revealed that there was an increase in same-sex experience in both men and women between 2001–02 and 2012–1320 and this may be due to the increasing trend in sexual fluidity, where there are shifts in one’s personal comprehension of their sexual orientation identity, irrespective of whether they have shared this with others or not.21 This was also evidenced by a US study, which showed that 17% changed their sexual orientation or identity from one to another, and 33% changed their attraction to one or more genders with the largest change observed among youth aged 14–17 years.22 Alongside other LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual and other sexually or gender diverse) teenagers, sexual fluidity is more common in adolescent MSM.23

There have been very limited studies that specifically sampled adolescent MSM and therefore, the magnitude of changes in sexual practice among adolescent MSM is unclear. There has been one Australian study examining the sexual practice and trajectory among MSM aged 16–20 years in 2010–2012.24 We employed the same methodology and repeated the previous study in 2017–2018 aiming to examine the sexual practice and trajectory among adolescent MSM, to examine whether there have been any changes after 5 years.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This study was a secondary analysis of Human Papillomavirus in Young People Epidemiological Research 2 (HYPER2), which was a cross-sectional study aimed to examine the HPV prevalence among young MSM who were eligible for the national gender-neutral school-based HPV vaccination program in Australia (NCT03000933). The main findings on HPV prevalence from this study have been published elsewhere.25 We conducted secondary analyses aimed to examine the sexual trajectory of this cohort, which was not included in the previous manuscript. Aspects of this study had been used to compare with secondary analysis of Human Papillomavirus in Young People Epidemiological Research 1 (HYPER1). HYPER1 and HYPER2 employed similar study designs and recruitment strategies to recruit MSM aged 16–20 years in Melbourne, Australia. Participants in both HYPER1 and HYPER2 studies were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their sexual activities.24

Data collection

The HYPER2 study recruited men aged 16–20 years, self-identified as same-sex attracted and had resided in Australia since 2013. Participants were recruited from the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre and the community including gay community events, universities, smartphone dating applications, and social networking services (e.g. Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) in Melbourne, Australia, in 2017–2018. A clinician-collected anal swab and self-collected penile swab and oral rinse were tested for HPV genotypes for the primary study outcomes. Additionally, participants were asked to complete a self-administered paper-based questionnaire as part of the study. Similarly, the HYPER1 study recruited men aged 16–20 years, self-identified as same sex attracted men between 2010 and 2012 using similar recruitment strategies.24

The questionnaire collected data on demographic characteristics (e.g. age, highest level of education), sexual practices with men and women (e.g. the number of sexual partners in a lifetime and the past 12 months, condom use, usual sex role during anal sex (top, bottom or versatile) and the age of first sex (year and month). This analysis focused on the age of first sex. For participants who had had sex with another man, we asked the age of first sex for the following activities: performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, insertive anal sex and receptive anal sex. For participants who had had sexual experience with women, we asked the age of first sex for the following activities: performing oral sex, receiving oral sex and vaginal sex.

To examine sexual mixing by age and country of birth, we also asked the participants to report the number of sexual partners they had had sex with of the same age, were younger, were older, and did not grow up in Australia. Participants each received an AUD30 voucher to compensate for their time.

Statistical analysis

Median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported for continuous variables such as the age at first individual sexual activities, and the number of sexual partners. Frequencies and proportions were reported for all categorical variables such as condom use. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed to present the cumulative probability by age of men having had first sex, stratified by the gender of partners and type of sexual activities. We also included the median age at first sex from the HYPER1 as a comparison. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata ver. 17 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

There were 200 men recruited in the HYPER2 study with a median age of 18.8 years (IQR: 18.6–20.2). Most men completed secondary school (71.5%, 143/200; Table 1). The majority of participants were recruited from sexual health clinics (79.5%, 159/200), followed by community organisations and events (20.5%, 41/200). All participants in this study had ever had sex with another man (100%, 200/200), and a substantial proportion (26.0%, 52/200) of men had ever had sex with a woman.

| n | Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 200 | 18.8 (IQR: 18.6–20.2) | |

| Education, n (%) | 199 | 99.5% | |

| Year 10 or less | 7 | 3.5% | |

| Year 11 | 17 | 8.5% | |

| Year 12 | 143 | 71.9% | |

| TAFE | 12 | 6.0% | |

| University | 19 | 9.5% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Usual anal sex role, n (%) | 192 | 96.0% | |

| Top | 45 | 23.4% | |

| Bottom | 90 | 46.9% | |

| Versatile | 47 | 24.5% | |

| Unsure | 3 | 1.6% |

Sex with men

The median age for any type of sexual contact with a man was 17.6 years (IQR: 16.3–18.3). The most common sexual practice with male partners was performing oral sex (97.5%), followed by receiving oral sex (97.0%), receptive anal sex (82.5%) and insertive anal sex (69.0%) (Table 2). With a male partner, the median age at the first time performing oral sex was 17.2 years (IQR: 16.0–18.2) and 17.3 (IQR: 16.1–18.3) for receiving oral sex. The median age at the first time having insertive anal sex was 18.0 years (IQR: 17.0–18.5) and having receptive anal sex was 18.0 years (IQR: 16.3–18.4). The median age at first sex in HYPER2 was slightly older compared to HYPER1: receiving oral sex (16.5 years), performing oral sex (16.4 years), receptive anal sex (17.0 years) and insertive anal sex (17.3 years).

| Sexual practices | Statistics, median (IQR range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex with men | ||

| Had male sexual partners in lifetime, n (%) | 200 (100%) | |

| Number of male sexual partners in lifetime | 10 (2–25) | |

| Had male sexual partners who did not grow up in Australia in lifetime, n (%) | 92 (46%) | |

| Number of male partners who did not grow up in Australia in lifetime | 3 (1.5–6) | |

| Tongue kissing | ||

| Number of tongue-kissed male sexual partners in lifetime | 12 (5–30) | |

| Performing oral sex A | ||

| Had performed oral sex with men in lifetime, n (%) | 195 (97.5%) | |

| Age at first performing oral sex | 17.2 (16.0–18.2) | |

| Number of performing oral sex partners in past 12 months | 5 (2–10) | |

| Number of performing oral sex partners in lifetime | 8 (3–20) | |

| Receiving oral sex B | ||

| Had received oral sex with men in lifetime, n (%) | 194 (97%) | |

| Age at first receiving oral sex | 17.3 (16.1–18.3) | |

| Number of receiving oral sex partners in past 12 months | 5 (2–10) | |

| Number of receiving oral sex partners in lifetime | 8 (3–20) | |

| Insertive anal sex C | ||

| Had insertive anal sex (defined as sex with a man where the participant’s penis is in the partner’s anus, the participant was on top) with men in lifetime, n (%) | 138 (69%) | |

| Age at first insertive anal sex | 18 (17–18.5) | |

| Number of insertive anal sex partners in past 12 months | 2 (1– 5) | |

| Number of insertive anal sex partners in lifetime | 4 (2–10) | |

| Used a condom during last insertive anal sex, n (%) | 80 (58%, 80/138) | |

| Number of insertive anal sex partners in past 12 months using a condom all the time (100%) | 1 (1– 4) | |

| Number of insertive anal sex partners in lifetime using a condom all the time (100%) | 2 (1–7) | |

| Receptive anal sex D | ||

| Had receptive anal sex with men in lifetime, n (%) | 164 (82.5%) | |

| Age at first receptive anal sex | 18 (16.3–18.4) | |

| Number of receptive anal sex partners in past 12 months | 3 (1– 6.5) | |

| Number of receptive anal sex partners in lifetime | 4 (2–10) | |

| Used a condom during last receptive anal sex, n (%) | 94 (57.3%, 94/164) | |

| Number of receptive anal sex partners in past 12 months using a condom all the time (100%) | 2 (1–5) | |

| Number of receptive anal sex partners in lifetime using a condom all the time (100%) | 2 (1– 8) | |

| Age mixing | ||

| Had male partners who were older than the participant in lifetime, n (%) | 187 (93.5%) | |

| Number of male partners who were older than the participant in lifetime | 6 (3–20) | |

| Age (years) difference with the oldest man | 14 (8–27) | |

| Had male partners who were younger than the participant in lifetime, n (%) | 87 (43.5%) | |

| Number of male partners who were younger than the participant in lifetime | 2 (1–5) | |

| Age (years) difference with the youngest man | 3 (1.5–6) | |

| Had male partners who were the same age as the participant, n (%) | 138 (69.0%) |

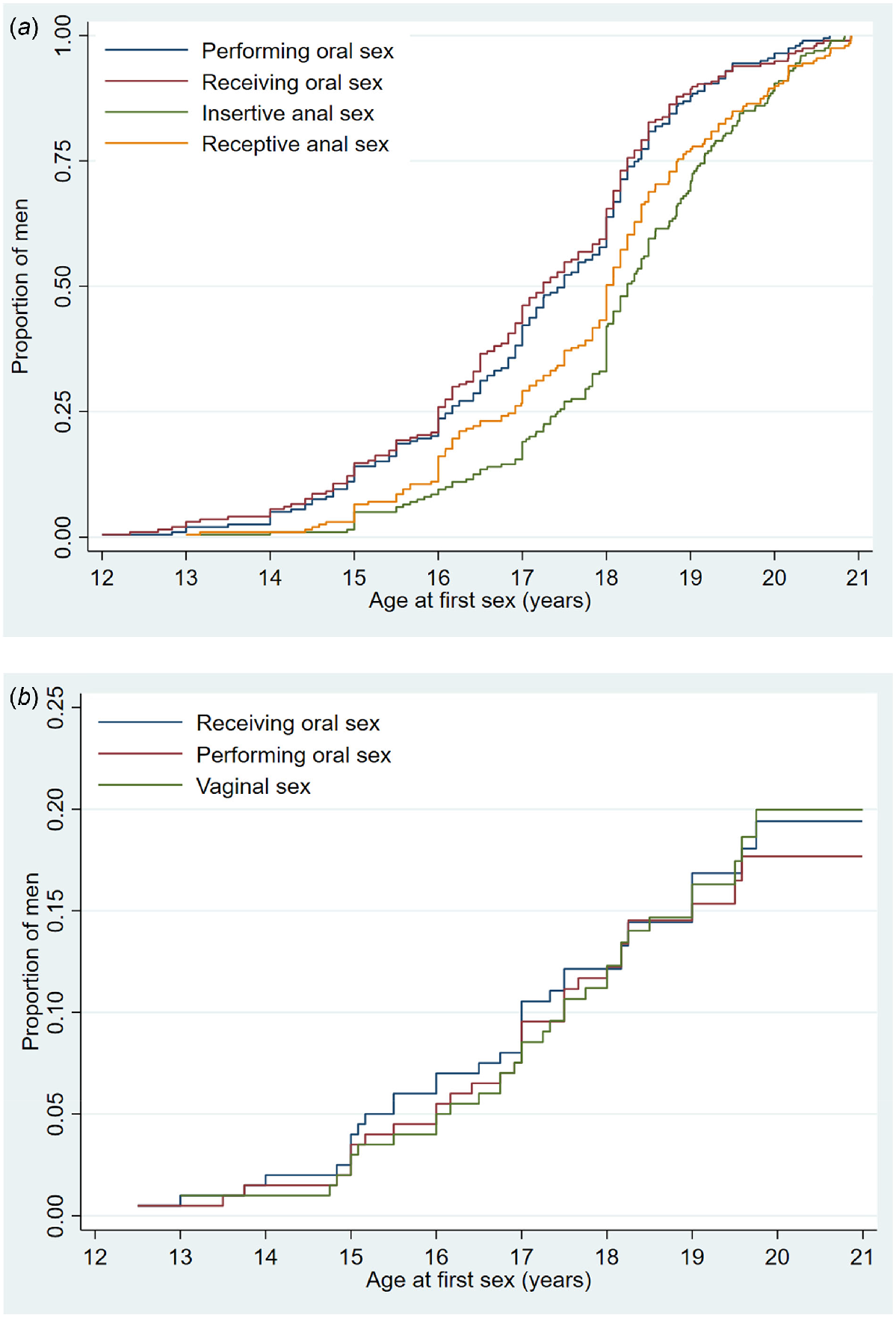

By the age of 19, 89.5%, 81.7%, 74.9% and 62.0% of men had receptive oral sex, insertive oral sex, receptive anal intercourse and insertive anal sex with men, respectively (Fig. 1a).

(a) Age at which teenage MSM first engaged in specific sexual behaviours with men. (b) Age at which teenage MSM first engaged in specific sexual behaviours with women.

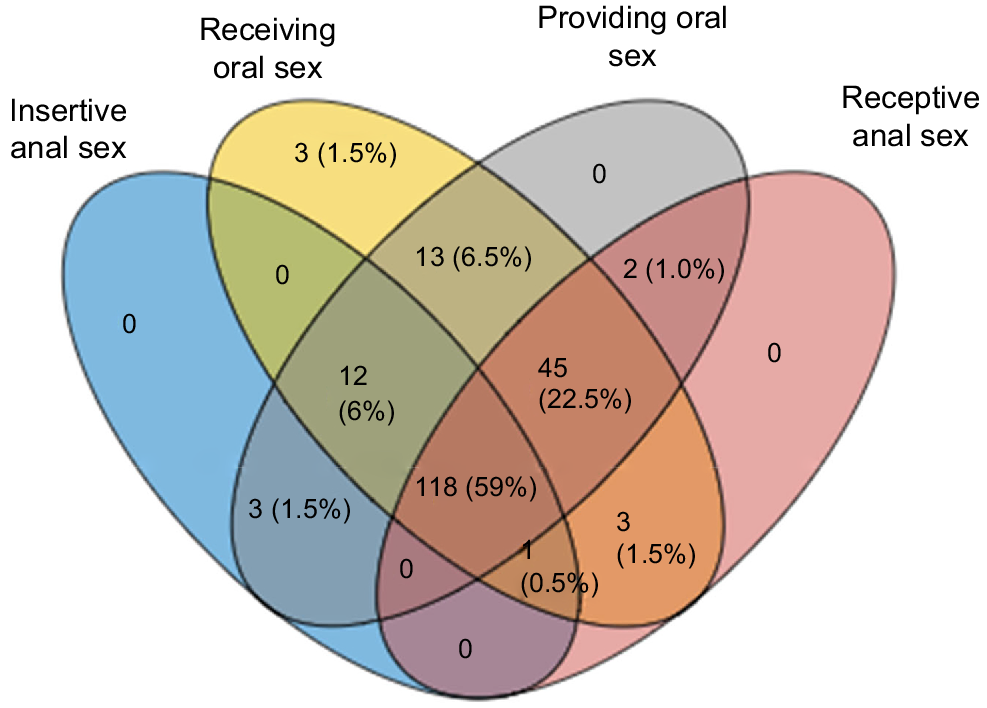

More than half (59.0%, 118/200) had ever engaged in all four types of sexual activities with another man. Only a small proportion of men (1.5%, 3/200) had ever engaged in only one activity (i.e. receiving oral sex). All men who had had anal sex also had oral sex (Fig. 2).

A four-set Venn diagram illustrating the combination of different sexual practices with men among 200 adolescent men who have sex with men in the HYPER2 study.

Study participants were more likely to have older male partners than younger male partners. Among those who reported having older male partners (93.5%, 187/200), a median of six partners (IQR: 3–20) were older and partners were a median of 14 (IQR: 8–27) years older than the study participants. Among those who reported having younger male partners (43.5%, 87/200), a median of two partners (IQR: 1–5) were younger and partners were a median of 1 (IQR: 1–2) years younger than men in the study. In addition, 138 study participants (69.0%, 138/200) reported having male partners of a similar age. Moreover, almost half (46.0%, 92/200) reported having male partners who did not grow up in Australia, with a median number of 3 (IQR: 1.5–6) male partners who did not grow up in Australia.

Sex with women

The median age for any type of sexual contact with a woman was 16.5 years (IQR: 15–17.5). The most common sexual practice with female partners was receiving oral sex (17%), followed by vaginal sex (16.5%) and performing oral sex (15.5%). With a female partner, the median age at first receiving oral sex was 17.0 years (15.1–18.0) and performing oral sex was 17.0 years (IQR: 15.2–18.0) and vaginal sex was 17.0 years (IQR: 16.0–18.2). The median age at first sex in HYPER2 was slightly older compared to HYPER1: performing oral sex (16.8 years), receiving oral sex (16.3 years) and vaginal sex (16.7 years).

By the age of 19, 16.9%, 16.3% and 15.1% of men had insertive oral sex, vaginal intercourse and receptive oral sex respectively with women.

Fig. 1b shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the cumulative proportion that reported each type of sex with a woman by a particular age and there were some differences around the age of 18 years. Most men reported receiving oral sex as their first sexual activity with women between the ages of 15 and 17 years. However, there was no clear trend on the temporal nature of each of the three sexual practices since the age of 18 years.

The number of participants who had sex with women was 52 (26.0%, 52/200; Table 3). Among those who reported having older female partners (40.4%, 21/52), a median of three partners (2–12) were older and partners were a median of 8 years (IQR: 2–14) older than men in the study. Among those who reported having younger female partners (30.8%, 16/52), a median of 1.5 partners (IQR: 1–2.5) were younger and partners were a median of 1 year (1–2) younger than men in the study. In addition, 51 study participants (82.7%, 43/52) reported having female partners of a similar age. Furthermore, 16 study participants (23.1%, 12/52) reported having had female partners who did not grow up in Australia, with a median number of 1 (IQR: 1–4) partners who did not grow up in Australia.

| Sexual practices | Statistics, median (IQR range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex with women | ||

| Had female sexual partners in lifetime, n (%) | 52 (26%, 52/200) | |

| Number of female sexual partners in lifetime | 2 (1–7.5) | |

| Had female partners who did not grow up in Australia, n (%) | 16 (23.1%, 12/52) | |

| Number of female partners who did not grow up in Australia | 1 (1– 4) | |

| Number of tongue-kissed female sexual partners in lifetime | 3 (1– 7) | |

| Receiving oral sex A | ||

| Had received oral sex with women in lifetime, n (%) | 34 (17%) | |

| Age at first receiving oral sex | 17 (15.1–18.2) | |

| Number of receiving oral sex partners in past 12 months | 1 (1–5) | |

| Number of receiving oral sex partners in lifetime | 3 (1–9) | |

| Performing oral sex B | ||

| Had performed oral sex with women in lifetime, n (%) | 31 (15.5%) | |

| Age at first performing oral sex | 17 (15.2–18) | |

| Number of performing oral sex partners in past 12 months | 2 (1–5) | |

| Number of performing oral sex partners in lifetime | 2.5 (1–8) | |

| Vaginal sex C | ||

| Had vaginal sex with women in lifetime, n (%) | 33 (16.5%) | |

| Age at first vaginal sex | 17 (16–8.2) | |

| Number of vaginal sex partners in past 12 months | 1 (1–5) | |

| Number of vaginal sex partners in lifetime | 3 (1–9) | |

| Used a condom during last vaginal sex, n (%) | 21 (63.6%) | |

| Number of vaginal sex partners in past 12 months using a condom all the time (100%) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Number of vaginal sex partners in lifetime using a condom all the time (100%) | 1 (1–6) | |

| Age mixing | ||

| Had female partners who were older than the participant in lifetime, n (%) | 21 (40.4%, 21/52) | |

| Number of female partners who were older than the participant in lifetime | 3 (2–12) | |

| Age (years) difference with the oldest woman | 8 (2–14) | |

| Had female partners who were younger than the participant in lifetime, n (%) | 16 (30.8%, 16/52) | |

| Number of female partners who were younger than the participant in lifetime | 1.5 (1–2.5) | |

| Age (years) difference with the youngest woman | 1 (1–2) | |

| Had female partners who were the same age as the participant | 1 (1–4) |

Discussion

In this study, we found that most adolescent MSM, who had a median age of 18.8 years, had engaged in oral sex first, followed by anal sex with their male partners. Most men performed and received oral sex around the same age: however, men experienced receptive anal sex before engaging in insertive anal sex (Fig. 1a). This contrasts with the experience with female partners where performing oral sex, receiving oral sex and vaginal sex occurred around the same age.

Most adolescent MSM had engaged in both oral and anal sex, with only three men only having oral sex but not anal sex, suggesting anal sex is common among adolescent MSM. We also found that there is a temporal sequence of different sexual practices among adolescent MSM with their male sexual partners. MSM tends to engage first in receiving oral sex, followed by performing oral sex, receptive anal sex (bottom) and insertive anal sex (top), this temporal sequence is consistent with the HYPER1 study, a cohort with similar demographics and recruitment strategy recruited in Melbourne, 2010–2012.24

Adolescents view oral sex as a way to improve their romantic relationships.26 Oral sex may aid in an individual’s sexual exploration and facilitate orgasm as their sexual experience progresses, especially in those who perform oral sex.27 However, we found that there was, in general, a small delay in first-sex activity in the HYPER2 cohort compared to HYPER1 although the number of partners in the past 12 months was the same between the two cohort studies.24 Additionally, we also saw an increase in condom use between the two studies, the proportion of MSM who used condoms during the last insertive anal sex increased from 35% to 58%, and receptive anal sex from 38.2% to 57% in HYPER1 and HYPER2, respectively. This is important to note that almost half of adolescent MSM did not use condoms for anal sex. Sexual health education on condom use, regular HIV/STI check-ups and other prevention strategies (e.g. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis) should be tailored and targeted adolescent MSM specifically.

Approximately one in four (26%, 52/200) adolescent MSM has also had sex with a female and this proportion was lower than in HYPER1 (42.5%, 85/200).24 Similar patterns on delayed sexual debut were also observed among men who had sex with women in HYPER2 compared to HYPER1.24 The findings from HYPER1 are also similar to the IMPRESS study, a cohort of 191 heterosexual men aged 17–19 years in Melbourne in 2014–2015, showing the median age of first oral sex was 16.4 years and vaginal sex was 16.9 years.28 The delayed sexual debut is also supported by a national population survey of 20,094 Australian men and women 16–59 years old from 2001–2002 and 2012–2013, where the proportion of men reporting first vaginal intercourse before age 16 years fell from 22% to 19%, and the median age at first vaginal intercourse among men rose from 17.6 years to 17.9 years.29 However, our Kaplan–Meier curve shows that there were some changes before and after the age of 18. It appears that men at the age of 15–17 years received oral sex first, followed by performing oral sex and vaginal sex with their female partners. However, this pattern disappeared after the age of 18 years. Oral sex is perceived to be less risky than vaginal sex in terms of health, social, and emotional consequences and current literature suggest that a far greater number of adolescents engage in oral sex than vaginal sex at young ages.30 It has been suggested that adolescents engage in oral sex to achieve sexual pleasure and intimacy, while avoiding pregnancy and STIs26 and they perceive oral sex as more acceptable than vaginal sex for those who are under 18 years and are less of a threat to their values and beliefs.30 Previous studies have found that teenagers see oral sex as a way of preserving their virginity while allowing intimacy and sexual pleasure.30

Past studies have shown that increased sexual education is associated with delayed sexual initiation, reducing the risk of teenage pregnancies, the frequency of sexual intercourse, and increasing the use of condoms and other contraceptive methods.24,26,27 In 2014, the national curriculum was developed by the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority for sex and respectful relationships in Australian schools, which included key points including ‘reproduction and sexual health practices that support reproductive and sexual health (contraception, negotiating consent, and prevention of STIs and blood-borne viruses)’.31 The addition of this curriculum may have led to some behavioural changes among the Australian population; however, we were unable to conclude this causality as this study was not designed to answer this research question. Although there were no outcome measures of the curriculum change, one international study in Mexico examined the impact of having a comprehensive sexual education program and they found that students at control schools (i.e. schools that did not have a comprehensive sexual education program) had high odds (OR = 4.77, 95% CI: 2.41–9.43) of early sex debut compared with those intervention schools (schools that received a comprehensive sexual education program).32 Therefore, further implementing comprehensive sexual education programs may be a key strategy. These programs should cover topics such as sexual and reproductive health, contraception, negotiation of consent, and prevention of STIs. These programs could empower young people to make informed decisions before sex. Future research can determine the impact of these programs over time, providing valuable insights into their effectiveness and informing future policy decisions.

Sexual mixing refers to whom individuals choose as sexual partners and is described as assortative on a characteristic, if individuals tend to choose partners similar to themselves for that characteristic.33 We found that our study participants tend to have partners with different ages and countries of birth, which is similar to other previous studies.34–36 This should be a consideration for the benefits of a universal gender-neutral vaccination scheme/one that includes men. A Canadian study has found a higher than expected number of heterosexual partnerships where partners have similar characteristics for age, country of birth, ethnicity, financial situation growing up, smoking behaviour and lifetime number of sex partners.33 This may be reflected in the data collected or may reflect the multicultural and diverse nature of the Australian population, since 29.3% of Australia’s population, excluding those with a birthplace not stated) were born overseas in the 2021 Census.37

It is important to note that this study has several limitations. First, most of the men recruited were from sexual health clinics in Australia, which may have been biased towards sexually active men, and therefore, our data may not be generalisable to all teenage MSM in Australia. Second, one of the inclusion criteria for HYPER2 was the participants had to be residents of Australia since 2013 to ensure they were eligible for the national HPV vaccination program. However, Australian residency was not part of the eligible criteria in HYPER1, and therefore, the comparison between the two cohorts is also possibly due to more restricted inclusion criteria in HYPER2, although there was no difference in the number of male sex partners in the past 12 months between the two studies. Additionally, our data may not be generalisable to other groups, including individuals from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds and in other countries and settings. Finally, self-reporting and recall bias may have occurred in this study since participants were required to recall their first sexual experience.

Conclusion

We found that there is a delay observed in first-sex activity across all sexual practices (performing and receiving oral sex, performing and receiving anal sex with men, performing and receiving oral sex and performing vaginal sex with women) reported in the HYPER2 (performed in 2017–2018) cohort compared to HYPER1 (2010–2012). Additionally, we also saw an increase in condom use between the two studies. This may be due to increased education in sexual health: therefore, future government initiatives on sexual practice and sexual health education could be implemented to increase condom usage even further. Although a higher proportion of HYPER1 participants reported sexual contact with females, those who reported sexual contact with females in HYPER2 had engaged in more sexual practices with more female partners. This may reflect sexual fluidity and reflect a change in attitudes between the two study cohorts. This provides further evidence that sexual education programs should include discussions of all potential sex practices between people of any sexual or gender identity to be more effective.

STIs continue to rise in Australia, particularly among MSM: understanding their sexual practices is important for STI prevention and the development of future interventions. Although delayed sexual initiation and increased condom use were seen in the HYPER2 cohort, this population still sees high levels of STI rates in the wider Australian context.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of interest

EPFC is an Associate Editor of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they were blinded from the review process. All other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Declaration of funding

EPFC is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172873). CKF and CSB are supported by an Australian NHMRC Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172900 and GNT1173361, respectively). EPFC has received educational grants from Seqirus Australia and bioCSL to assist with education, training, and academic purposes in the area of HPV, outside the submitted work. EPFC has received occasional speaker’s honoraria from Merck outside the submitted work. CKF has received research funding from CSL Biotherapies and owns shares in CSL Biotherapies. SMG has received advisory board fees and lecture fees from Merck for work in private time and through their institution (Royal Women’s Hospital) funding for an investigator-initiated grant from Merck for a young women’s study on HPV, and is a member of the Merck Global Advisory Board for HPV vaccination. EPFC, MYC, CKF and SMG received the investigator-initiated grant to conduct the HYPER2 study from Merck.

Author contributions

The HYPER study investigators include EFPC, MYC, CKF and SMG. EFPC and MYC convinced and designed the study with the input from CKF. RB collected data and designed recruitment strategy. CW performed data analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EPFC provided statistical advice and supervised the project. All authors helped to interpret results and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

1 Coleman A, Tran A, Hort A, Burke M, Nguyen L, Boateng C, et al. Young Australians’ experiences of sexual healthcare provision by general practitioners. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48(6): 411-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Delany-Moretlwe S, Cowan FM, Busza J, Bolton-Moore C, Kelley K, Fairlie L. Providing comprehensive health services for young key populations: needs, barriers and gaps. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18(2 Suppl 1): 19833.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, Jun 2012 2012 [updated 25/092012]. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/4102.0main+features10jun+2012

4 King J, McManus H, Kwon JA, Gray R, McGregor S. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia - Annual surveillance report 2023. Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney; 2023. Available at https://www.kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/Annual-Surveillance-Report-2023_STI.pdf

5 Institute UK. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia Annual surveillance report 2022. 2022. Available at https://www.kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/Annual-Surveillance-Report-2022_STI.pdf.

6 Chow EPF, Grulich AE, Fairley CK. Epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men at risk of HIV. Lancet HIV 2019; 6(6): e396-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Li J, Li S, Yan H, Xu D, Xiao H, Cao Y, et al. Early sex initiation and subsequent unsafe sexual behaviors and sex-related risks among female undergraduates in Wuhan, China. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015; 27(2): 21S-9S.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Magnusson BM, Masho SW, Lapane KL. Early age at first intercourse and subsequent gaps in contraceptive use. J Womens Health 2012; 21(1): 73-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Baumgartner JN, Waszak Geary C, Tucker H, Wedderburn M. The influence of early sexual debut and sexual violence on adolescent pregnancy: a matched case-control study in Jamaica. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009; 35(1): 21-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Ma Q, Ono-Kihara M, Cong L, Xu G, Pan X, Zamani S, et al. Early initiation of sexual activity: a risk factor for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV infection, and unwanted pregnancy among university students in China. BMC Public Health 2009; 9: 111.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Stryhn JG, Graugaard C. [The age at first intercourse has been stable since the 1960s, and early coital debut is linked to sexual risk situations]. Ugeskr Laeger 2014; 176(37): V01140063.

| Google Scholar |

12 Olesen TB, Jensen KE, Nygård M, Tryggvadottir L, Sparén P, Hansen BT, et al. Young age at first intercourse and risk-taking behaviours--a study of nearly 65 000 women in four Nordic countries. Eur J Public Health 2012; 22(2): 220-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Yode M, LeGrand T. Association between age at first sexual relation and some indicators of sexual behaviour among adolescents. Afr J Reprod Health 2012; 16(2): 173-88.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Sandfort TGM, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Santelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: results from a national US study. Am J Public Health 2008; 98(1): 155-61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Epstein M, Bailey JA, Manhart LE, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, et al. Understanding the link between early sexual initiation and later sexually transmitted infection: test and replication in two longitudinal studies. J Adolesc Health 2014; 54(4): 435-41.e2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Upchurch DM, Mason WM, Kusunoki Y, Kriechbaum MJ. Social and behavioral determinants of self-reported STD among adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004; 36(6): 276-87.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Fam Plann Perspect 1998; 30(6): 271-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Greenberg J, Magder L, Aral S. Age at first coitus. A marker for risky sexual behavior in women. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19(6): 331-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Power J, Kauer S, Fisher C, Bellamy R, Bourne A. 7th National survey of secondary students and sexual health 2022. La Trobe University; 2022. Available at https://www.latrobe.edu.au/arcshs/work/national-survey-of-secondary-students-and-sexual-health-2022.

20 Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Badcock PB, Smith AM, Heywood W, Richters J, et al. Homosexual experience and recent homosexual encounters: the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex Health 2014; 11(5): 439-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Diamond L. Sexual fluidity in male and females. Curr Sex Health Rep 2016; 8: 249-56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Katz-Wise SL, Ranker LR, Gordon AR, Xuan Z, Nelson K. Sociodemographic patterns in retrospective sexual orientation identity and attraction change in the sexual orientation fluidity in youth study. J Adolesc Health 2023; 72(3): 437-43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Srivastava A, Hall WJ, Krueger EA, Goldbach JT. Sexual identity fluidity, identity management stress, and depression among sexual minority adolescents. Front Psychol 2022; 13: 1075815.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Zou H, Prestage G, Fairley CK, Grulich AE, Garland SM, Hocking JS, et al. Sexual behaviors and risk for sexually transmitted infections among teenage men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health 2014; 55(2): 247-53.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Chow EPF, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Wigan R, Machalek DA, Garland SM, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in young men who have sex with men after the implementation of gender-neutral HPV vaccination: a repeated cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21(10): 1448-57.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Cornell JL, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents tell us why teens have oral sex. J Adolesc Health 2006; 38(3): 299-301.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Pakpahan C, Darmadi D, Agustinus A, Rezano A. Framing and understanding the whole aspect of oral sex from social and health perspectives: a narrative review. F1000Res 2022; 11: 177.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Chow EPF, Wigan R, McNulty A, Bell C, Johnson M, Marshall L, et al. Early sexual experiences of teenage heterosexual males in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2017; 7(10): e016779.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 de Visser RO, Richters J, Rissel C, Badcock PB, Simpson JM, Smith AM, et al. Change and stasis in sexual health and relationships: comparisons between the first and second Australian studies of health and relationships. Sex Health 2014; 11(5): 505-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Tanne JH. US teenagers think oral sex isn’t real sex. BMJ Open 2005; 330(7496): 865.

| Google Scholar |

31 Young Pregnant and Parenting Network. National curriculum on sex and respectful relationships. Available at https://youngpregnantandparenting.org.au/sex-and-relationships-ed/national-curriculum-on-sex-and-respectful-relationships/

32 Ramírez-Villalobos D, Monterubio-Flores EA, Gonzalez-Vazquez TT, Molina-Rodriguez JF, Ruelas-Gonzalez MG, Alcalde-Rabanal JE. Delaying sexual onset: outcome of a comprehensive sexuality education initiative for adolescents in public schools. BMC Public Health 2021; 21(1): 1439.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Malagón T, Burchell A, El-Zein M, Tellier PP, Coutlée F, Franco EL, et al. Assortativity and mixing by sexual behaviors and sociodemographic characteristics in young adult heterosexual dating partnerships. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(6): 329-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Greaves KE, Fairley CK, Engel JL, Ong JJ, Rodriguez E, Phillips TR, et al. Sexual mixing patterns among male–female partnerships in Melbourne, Australia. Sex Health 2022; 19(1): 33-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Greaves KE, Fairley CK, Engel JL, Ong JJ, Aung ET, Phillips TR, et al. Assortative sexual mixing by age, region of birth, and time of arrival in male-female partnerships in Melbourne, Australia. Sex Transm Dis 2023; 50(5): 288-91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Chow EPF, Read TRH, Law MG, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK. Assortative sexual mixing patterns in male-female and male-male partnerships in Melbourne, Australia: implications for HIV and sexually transmissible infection transmission. Sex Health 2016; 13(5): 451-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

37 Australia PTU. People born (overseas) in predominantly English-speaking countries, 2021. 2021. Available at https://phidu.torrens.edu.au/notes-on-the-data/demographic-social/es-countries#:~:text=The%202021%20Census%20of%20Population,2016%20%5B1%5D%5B2%5D