Co-creation and community engagement in implementation research with vulnerable populations: a co-creation process in China

Liyuan Zhang A , Katherine T. Li B , Tong Wang A , Danyang Luo C , Rayner K. J. Tan D , Gifty Marley A , Weiming Tang A E , Rohit Ramaswamy F , Joseph D. Tucker

A E , Rohit Ramaswamy F , Joseph D. Tucker  E # and Dan Wu

E # and Dan Wu  G # *

G # *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

Top-down implementation strategies led by researchers often generate limited or tokenistic community engagement. Co-creation, a community engagement methodology, aims to create a shared leadership role of program beneficiaries in the development and implementation of programs, and encourages early and deep involvement of community members. We describe our experience using a four-stage co-creation approach to adapt and implement a sexually transmitted diseases (STD) testing intervention among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China.

We adapted a four-stage approach to co-creation. First, we conducted a needs assessment based on our prior work and discussions with community members. Second, we planned for co-creation by establishing co-creator roles and recruiting co-creators using both stratified convenience and opportunistic sampling. Third, we conducted co-creation via hybrid online/in-person focus groups (four multistakeholder groups and four MSM-only groups). Finally, we evaluated validity of the co-creation process through qualitative observations by research staff, analyzed using rapid qualitative analysis, and evaluated co-creator experience through post-discussion survey Likert scales and open-ended feedback.

Needs assessment identified the needs to adapt our STD intervention to be independently run at community-based and public clinics, and to develop explanations and principles of co-creation for our potential co-creators. In total, there were 17 co-creation members: one co-creation lead (researcher), two co-chairs (one gay influencer and one research assistant), eight MSM community members, four health workers (two health professionals and two lay health workers) and two research implementers and observers. Co-created contents for the trial included strategies to decrease stigma and tailor interventions to MSM at public STD clinics, strategies to integrate STD testing services into existing community-led clinics, and intervention components to enhance acceptability and community engagement. Our evaluation of validity identified three main themes: challenges with representation, inclusivity versus power dynamics and importance of leadership. Surveys and free responses suggested that the majority of co-creators had a positive experience and desired more ownership.

We successfully adapted a structured co-creation approach to adapt and implement an STD testing intervention for a vulnerable population. This approach may be useful for implementation, and further research is needed in other contexts and populations.

Keywords: co-creation, community engagement, empowerment, equity, implementation research, men who have sex with men, sexually transmissible diseases, vulnerable populations.

Background

Effective community engagement is linked to improved health outcomes across a variety of settings.1,2 Community engagement is defined by the World Health Organization as a process of developing relationships that enable stakeholders to work together to address health-related issues and promote well-being to achieve positive health impact and outcomes.3 Researchers have an ethical responsibility to engage a diverse range of stakeholders, especially those who are most affected by a program or intervention.4 Research funding agencies increasingly require that public health researchers and implementation scientists partner with community members or program beneficiaries.5

There are various approaches to include community members in research, each with a different balance of role, power and influence among key stakeholders. McCloskey et al. argue that community engagement can be regarded as a continuum of community involvement,1 ranging from an outreach level to a shared leadership with a strong bidirectional relationship.1 Researchers in public health have used a variety of community-engaged methods to engage diverse stakeholders. For instance, community advisory boards consist of community representatives that provide community feedback to the research project or initiative. Community advisory boards engage the community in a less active way, where community advisors mainly offer feedback to the project at researchers’ discretion.6 In contrast, co-creation aims to create a shared leadership role that involves the community in the development and design of programs from the beginning. Co-creators are empowered in the decision-making process for key implementation contexts, intervention components and implementation strategies, and/or fleshing out detailed steps to better meet their needs.

Despite an increasing use of co-creation and other community-engaged methods, there is a lack of clarity in defining, implementing and evaluating them.7 Researchers use terms, such as co-creation, co-design and co-production, interchangeably without distinctions or consensus definitions. Some examples of purported co-creation may not meet the shared leadership goal of co-creation and, in reality, result in only tokenistic engagement.7,8 In this paper, we adapt the definition and conceptual framework proposed by Vargas et al.9 on how to use these terms in public health research. We defined co-creation as ‘the collaborative approach of creative problem solving between diverse stakeholders at all stages of an initiative, from the problem identification and solution generation through to implementation and evaluation’.9 Further, program beneficiaries are regarded as experts through their lived experience, and serve with researchers as equal members of the design team.10,11

Co-creation has been extensively used in sexual health research, particularly in STD prevention.12 Designing contextually appropriate interventions in diverse cultural and geographical settings is key to addressing sexual health challenges. However, very few studies have used co-creation among key populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM). Moreover, there is no consensus on how co-creation should be carried out.13 Co-creation evaluations are also sparse, and it is unclear whether co-creation processes actually result in effective, high-level community engagement,7 especially for sensitive or stigmatized topics when stakeholders may be less willing to participate.14

The goal of this paper was to describe and evaluate a co-creation process to design and implement a sexual health intervention for MSM in China. Our earlier trials showed the preliminary effectiveness of this intervention for increasing gonorrhea and chlamydia test uptake.15,16 We adopted the co-creation approach to adapt and implement our gonorrhea and chlamydia testing service across multiple public STD clinics and MSM community-based organizations (CBOs) in Guangdong Province.

Methods

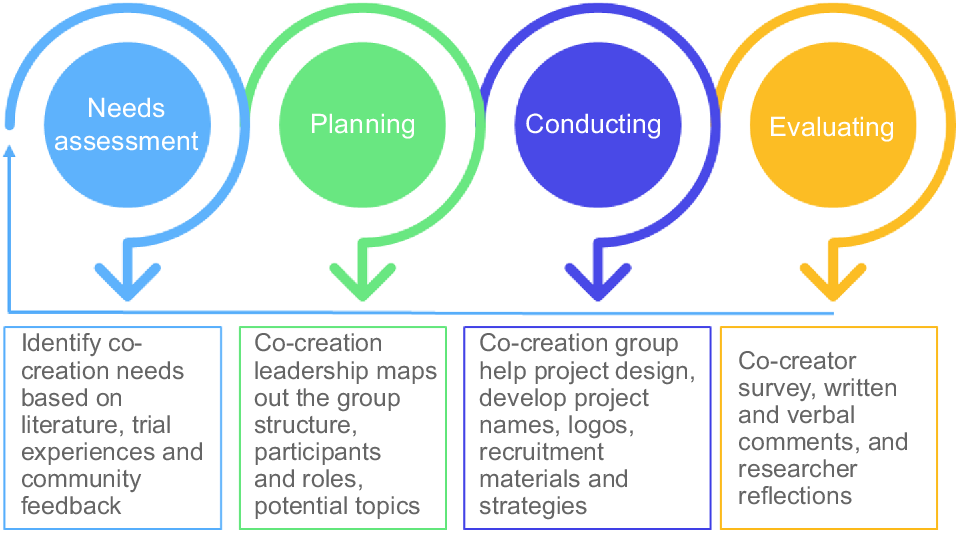

Our co-creation model was guided by the principles and recommendations for co-creation of public health interventions derived by Leask et al.17 The adapted four stages included: (1) needs assessment (literature review, trial experiences and community feedback), (2) planning (co-creation leadership, group structure, roles and participants, and potential topics for group discussion), (3) conducting (co-creation group help with project design, develop project names, logos, recruitment materials and strategies), and (4) evaluating (co-creator surveys, comments and researcher reflections). Stages (2–4) can iteratively feed back towards stage (1) and dynamically inform problems/tasks to be solved through co-creation. Fig. 1 illustrates how we used the four steps of the co-creation process for our study. Ethical approval was obtained through The University of Carolina at Chapel Hill. All participants gave written informed consent and agreed to participate in the study. We analyzed our co-creation process though a Likert scale post-discussion survey and a rapid qualitative analysis methods based on observation notes and open-ended feedback.

Needs assessment

Needs assessment involves identifying the problem, stating the objective of co-creation and understanding the end-users of the process, as proposed in the framework proposed by Leask et al. (Fig. 1).17 In the beginning, we based our needs assessment on our prior experience with our gonorrhea and chlamydia intervention, and on discussions with MSM around the intervention and around co-creation. However, our needs assessment also included assessing the needs of potential co-creators. Needs assessment was an iterative process: prior to each session, a review of the prior co-creation feedback and needs assessment was conducted by the co-creation leaders.

Planning

Planning for co-creation involved establishing leadership, recruiting co-creators, sampling decisions and deciding on co-creation group structure.

We began by identifying roles for the co-creation process. Co-creation is coordinated by facilitators, who orient team members to the co-creation process, balance roles, address potential conflicts and clarify how participants’ input will be used.7 To develop an atmosphere that enables the equal contribution of all stakeholders, facilitators must ensure that sessions are relaxed, informal and free of jargon.8 Facilitators often utilize design tools – such as games, visualizations and probes tailored for use in the target context – to engage participants and spur creativity.18,19

We then mapped out key stakeholders to invite as co-creators, and the co-creation group structure, roles and responsibilities (Table 1). Key stakeholders included provider-side representatives (health professionals and leaders from community clinics) and community members. Additionally, two researchers from the project team would attend co-creation meetings and observe the group dynamics, reflect on the whole process, and iteratively used group feedback to optimize the co-created interventions and strategies.

| Roles | Backgrounds | Responsibilities in the co-creation process | |

|---|---|---|---|

Lead (n = 1) Lead (n = 1) | Project co-investigator with prior experiences of implementing the public health intervention | To oversee the process of the co-creation activities and ensure that activities meet the overall project need/purpose. Be observative, reflective, but less engaged during the activities. Jointly decide with co-chairs on key issues to be discussed in the process. | |

Facilitators (n = 2) Facilitators (n = 2) | One project research assistant with research training; one gay community influencer who has prior experiences of providing STD testing services to local gay communities | The project assistant coordinated the whole process, came up with draft lists of topics relevant to the project, discussed with the Lead and the other co-chair issues to be solved in the upcoming co-creation activity. The gay influencer reviewed all relevant materials and topics to be discussed, provided constructive feedback, and jointly decided with the Lead and research assistant co-chair on issues to be discussed with the group. Both served as moderators of the co-creation activities throughout the process. | |

Researcher implementers and observers (n = 2) Researcher implementers and observers (n = 2) | Two research fellows who have been intensively engaged in implementing the project | To observe the group dynamics, reflect on the whole process and iteratively use group feedback to optimize the intervention delivery during a pilot study. Presented and observed the discussions. Communicate with other project staff on co-creation activities and contribute to the interactively developed discussion topics. | |

Provider side representatives (n = 4) Provider side representatives (n = 4) | Two health professionals from public clinics; two lay health workers (gay men) from community-led clinics | To provide inputs on contextual information about clinical settings in both public and community-led clinics; advise on optimal user pathways for gay men, especially closeted ones, to learn about and navigate our intervention. | |

Community members (n = 8) Community members (n = 8) | Eight men who have sex with men including closeted gay men | To provide user perceptions on demand and needs, STD testing services provision in public and community-led clinics, co-produce intervention components (e.g. messages, postcards, videos) and engagement strategies. |

We invited potential co-creators through social network recruitment and online open recruitment. Health workers were recruited through our professional networks. Open recruitment for MSM community members was advertised on the WeChat public official account (a Chinese multifunctional social networking app similar to Facebook) of Social Entrepreneurship to Spur Health. Interested men filled in the recruitment survey and were assessed for eligibility (i.e. biologically assigned as male at birth, age >18 years and ever had sex with another man).

We followed the principles discussed by Leask et al. with respect to sampling, which are based on prior recommendations to recruit 6–12 participants for focus group studies.17 We aimed to recruit ~10–12 total co-creators to also allow for division into smaller groups. Initially, we used convenience sampling to recruit co-creators who seemed likely to remain engaged. We used stratified sampling across age, geographic location and occupation to ensure some diversity in our co-creators. However, we also later used opportunistic sampling to recruit additional MSM as our ongoing needs assessment suggested that more input from a wider range of MSM would be valuable.

Conducting

Ownership has been an important aspect of co-creation. To manifest ownership for this co-creation project, the research team planned to state ownership by affirming that all co-creators are equal contributors; enable the right of ownership through delivering clear and jargon-free information about the aims of co-creation and the related science of the project (including information about gonorrhea and chlamydia testing); and empower co-creators to act on ownership by giving autonomous tasks with deadlines and expectations from co-creators with agreement from the group.

Given changing local COVID-19 policies, we adopted a hybrid in-person and online approach to organizing the focus group discussions. The discussions were spaced out to accommodate participants’ different availability and minimize risks of exposure to COVID-19. Agendas were discussed between the Lead (DW) and the two co-chairs (DL and TW), and topics were agreed on before the group discussion occurred. Co-chairs coordinated, sent the agenda and discussion materials to co-creators in advance. Small tasks related to each discussion were sent a few days before to allow co-creators time to prepare.

During the discussions, two facilitators jointly moderated the discussions. Common focus group discussions techniques were used to create a comfortable environment for sharing, such as preparing refreshments and ice-breaking activities. After each group discussion, the leader and two facilitators immediately organized a de-briefing session to make shared decisions on gaps and solutions identified, milestones achieved, next steps and plans, and these steps iteratively occurred to inform the next group discussion throughout the process. After the last discussion, the co-creation leader reminded the group that their feedback will be integrated into the intervention to be pilot tested at various clinical settings, and they will be looped back for member checking and iterative improvements. We audio recorded all discussions along with field notes, observations, and reflections during and after each co-creation discussion. No personal details or identifiable information were recorded.

Three of these discussions were conducted in person, and the last discussion was shifted online because of COVID-19 interruptions. We created a presentation for each discussion to help up-skill co-creators regarding understanding gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and our evidence-based intervention. Each discussion lasted ~1.5–2 h and focused on different topics. Topics of these discussions were iteratively developed and refined based on previous ones. Specifically, the first discussion focused on service needs assessment and gaps, target population characteristics and stakeholder mapping, clinical settings and contexts, recruitment procedures at clinics, challenges and risks, and risk mitigation solutions; the second discussion focused on community engagement components during implementation and the potential of using digital technology to facilitate engagement; the third discussion focused on data collection tools and recruitment; and the final discussion focused on an update about the research design and refinement progress, and discussed the webpage design for digital engagement environments workflow.

All four MSM group discussions were conducted online considering participant preferences for privacy protection purpose and COVID-19 restrictions. These four group discussions were focused on addressing the following topics: (1) community engagement strategies, (2) content and format of trial communications and messaging (including text and video), (3) project recruitment and educational materials refinement, and (4) tailoring and localization of implementation strategies.

Evaluating

Based on Leask et al.’s framework,17 evaluation consists of two parts: (1) evaluating the effectiveness of the co-created intervention; and (2) evaluating the co-creation process. For part (1), the outputs of this co-creation process were tested in a randomized controlled trial that will be reported separately.20 For part (2), outcomes included both validity of the outcome and co-creator satisfaction and ownership.

For validity of the outcome, two observers made observation notes on co-creation group dynamics and content. The domains of observations included: (1) needs assessment and problems or topics based on group discussion, (2) co-created contents and suggestions from the group, (3) group dynamics, including overall engagement from the group, distribution of which co-creators did most of the talking and which did the least, any conflicts or disagreements that occurred, and any patterns in dynamics between individuals with different social identities and co-creator roles. Observation notes on the co-creation process were analyzed using rapid qualitative analysis by two researchers by identifying key themes within each domain. Results were used for iterative needs assessment and to plan for future co-creation meetings.

For co-creator satisfaction and ownership, we collected survey data on co-creator satisfaction with the process by asking the following 5-point Likert scale questions: satisfaction with co-creation discussions organization efficiency, formats, contents and flow (in-person discussions), or overall satisfaction with participation and factors influencing participation. We also collected open-ended questions to solicit generic feedback; suggestions and personal feelings were asked for both at the end of the post-discussion survey and the final group discussion.

Results

Needs assessment

Based on our research team’s experience with implementing this program at community-based organizations in Guangzhou and Beijing, we anticipated that implementing the program at community-based organizations and public clinics across different cities in Guangdong province would require adaptation of intervention components, and creation of implementation strategies and workflows. The end-users included men at both public STD and community-based clinics in China.

We initially discussed the idea of co-creation with several well-known MSM community influencers. However, they had not participated in any similar co-creative processes in the past. Based on this needs assessment, we identified the need to create some introductory explanations of co-creation, its purpose and its intended goals. As co-creation was a largely new endeavor for this application in this community, we also identified a need to define the scope of co-creation for the purposes of this project and refine this as the project evolved. Other needs were identified throughout the project, and included a need to adapt recruitment, develop workflows and create culturally appropriate promotional materials. After our initial multistakeholder groups, we also identified the need to hear more from MSM community members.

Planning

The co-creation leader was a project co-investigator (DW) who oversaw the process and ensured that activities met the overall project needs/purpose, but had fewer direct interactions with other co-creators to maximize decentralization of power. We identified two facilitators – an MSM influencer (DL) who helped with our previous pay-it-forward trials, and a research assistant who was new to our intervention (TW) – to co-chair the whole process. The two facilitators also served as moderators of all group discussions. The two facilitators and co-creation leader jointly made decisions around key aspects of the co-creation effort. During discussions, the researcher facilitator with a sociology background would mainly ask open questions, but did not bring in pre-assumptions during discussions, whereas the community facilitator would play a more active role in building rapport, moderating sessions and balancing power within the group (e.g. by inviting less active participants to share ideas).

We recruited a total of 17 co-creators over the course of the project. For the first round of multistakeholder co-creation discussions, we recruited six co-creators: two health professionals working in public clinics, two lay health workers working in community organizations and two MSM community members. Co-creators’ ages ranged from 24 to 53 years. Then, as our project appeared to require more input of MSM, we recruited additional MSM for a round of MSM community co-creation discussions, which consisted of six new MSM community members. Both groups included the two facilitators and two researcher observers. Of note, all co-creators were recognized as contracted consultants to be a part of the project team and to take up the allocated roles. Characteristics of the co-creators are shown in Table 2.

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 4 (23.5) | |

| 26–30 | 5 (29.4) | |

| 31–40 | 7 (41.2) | |

| ≥41 | 1 (5.9) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 (70.6) | |

| Female | 5 (29.4) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Homosexual | 6 (35.3) | |

| Heterosexual | 7 (41.2) | |

| Bisexual | 4 (23.5) | |

| Education | ||

| Undergraduate or below | 6 (35.3) | |

| Master’s degree | 8 (47.1) | |

| Doctoral degree | 3 (17.6) | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | ||

| <1500 | 1 (5.9) | |

| 1500–5000 | 1 (5.9) | |

| 5001–8000 | 4 (23.5) | |

| >8000 | 11 (64.7) | |

| Professional background | ||

| Advertising/media/design | 3 (17.6) | |

| Health care/public health | 3 (17.6) | |

| Student | 2 (11.8) | |

| Nonprofit organizations | 3 (17.6) | |

| Research | 5 (29.4) | |

| Other (unspecified) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Experience working or volunteering in CBO | ||

| Yes | 12 (70.6) | |

| No | 5 (29.4) | |

Conducting

Between 31 August 2021 and 22 November 2022, we conducted a total of eight focus group discussions with a total of 17 participants. The main outputs of the co-creation sessions were as follows:

The co-creation group noted that there was still substantial stigma associated with STDs, and that many MSM patients were afraid of disclosing their sexual orientation to other people, including healthcare providers. As our intervention involves public clinic sites, this could cause challenges in identifying and recruiting MSM. Our co-creators generated icons, symbols, images or slogans that were subtle, but still indicated affinity with the gay community, to help signpost potential participants to MSM-friendly clinics in the public sector. Co-creators also suggested increasing the presence of MSM staff at project sites to help gain trust, reduce stigma and improve acceptability in public clinics.

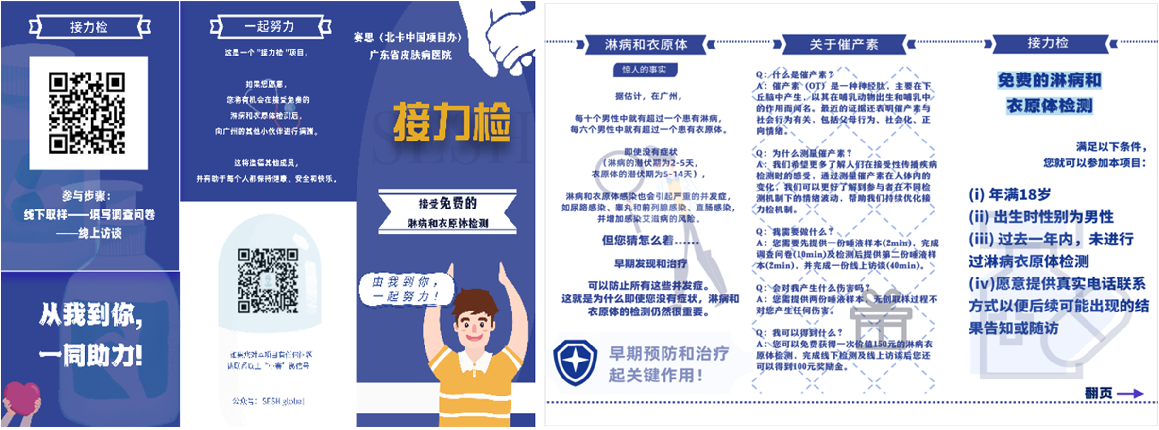

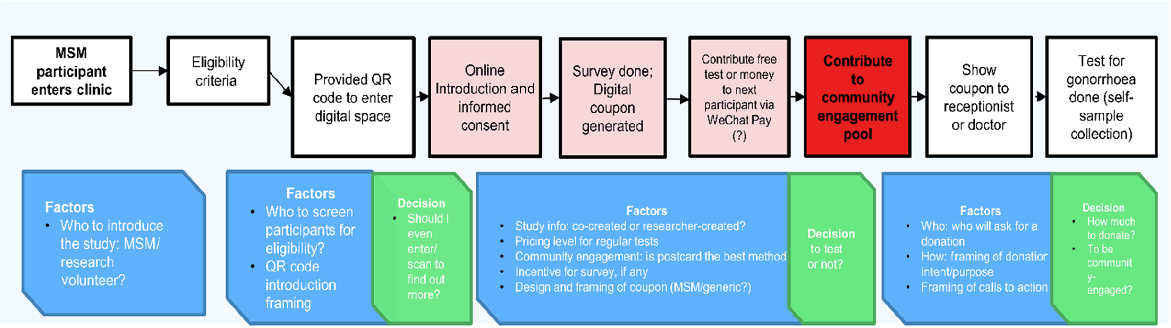

The community-led human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing clinics are trusted by the MSM community, but typically only provide rapid HIV, syphilis and hepatitis C blood testing, and lack infrastructure to provide gonorrhea or chlamydia polymerase chain reaction swabs. Furthermore, MSM co-creators suggested that they had a good understanding of HIV, but not on other STDs, such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. Thus, co-creators developed easy-to-understand educational pamphlet about gonorrhea and chlamydia to be disseminated among MSM to encourage testing (Fig. 2). Co-creators also helped with generating new workflows (Fig. 3) to integrate gonorrhea and chlamydia testing into existing workflows at clinics and CBOs.

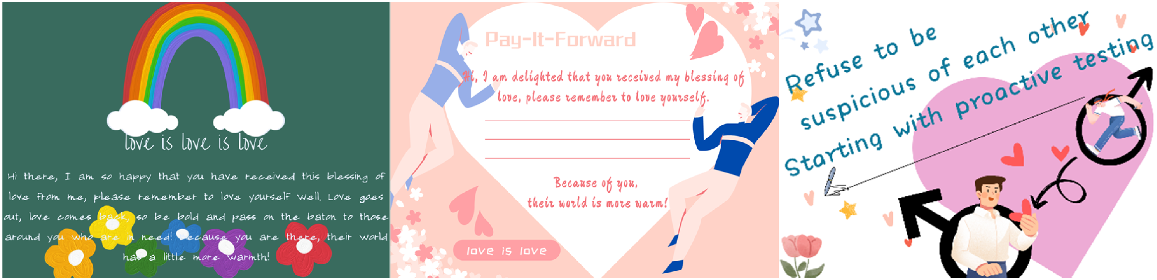

To make the intervention more acceptable and engaging, co-creators brainstormed additional online and offline components. Co-creators suggested an online engagement platform (Fig. 4: WeChat Mini-app main page) to engage participants and streamline their testing experience. The online platform is being developed as a WeChat mini-app that digitalizes key decision-making steps in participating pay-it-forward gonorrhea testing and donation behaviors. Co-creators also suggested more onsite activities involving the MSM community, including souvenirs or small gifts, to socially recognize participants’ inputs and engagement. Co-creators also helped design many of the intervention’s key promotional materials, including postcards to be used during the intervention (Fig. 5), re-conceptualized Chinese names for pay-it-forward, a project introductory video and project recruitment flyers (Fig. 6).

Evaluation

Observations from the facilitators and observers of the co-creation process, and open-ended feedback from co-creators throughout the co-creation process highlighted a few main themes about process validity:

Although the in-person part of the group discussions allowed greater opportunities for rapport building, and more dynamic interactions and information sharing, online participation made it more inclusive and accessible. Furthermore, all MSM community members agreed that the hybrid format helped alleviate men’s concerns about privacy, and would permit the participation of MSM who had not disclosed their sexual orientation. However, co-creators noted the exclusion of certain sociodemographic sub-groups of MSM, including older, less educated or married MSM. This may result in our intervention being less accessible to these groups, and hence cause them to be excluded from our testing intervention.

Despite our statement that all co-creators were equal participants, we still observed a power imbalance, especially in the multistakeholder group between healthcare professionals and MSM members. In these discussions, the physicians were more vocal, whereas the two MSM participants were relatively silent. We also observed relative reticence from MSM community members in conversations that involved MSM CBO leaders, who often held a higher position and had more experience in MSM-related sexual health service delivery. This led to our decision to organize another four focus groups including only MSM community members and researchers to further amplify MSM voices and mitigate potential distress.

Key to maintaining equity and ownership throughout the co-creation groups was the leadership of the facilitator, who was also a well-respected, well-known member of the MSM community. His shared identity as an MSM helped empower the MSM community to speak up. In addition, he was an experienced moderator, and was able to keep discussions on track and balance group dynamics, including politely cutting off those who dominated the conversation and gently encouraging reticent co-creators. His leadership also allowed the researcher facilitator to mainly asked open-ended questions without providing too many of their own views. This created an equitable, safe and comfortable environment where participants felt free to express themselves.

Sixteen out of 17 co-creators filled in our post-discussion surveys. Fifteen co-creators were very satisfied or satisfied with the discussion organization efficiency, formats, contents and flow. Comments solicited via the open-ended questions and at the end of the last focus group were generally positive. One MSM participant commented, ‘this is one of the rare examples that actually showed care about community members’ thoughts and interests in learning MSM needs in a research study’. All co-creators showed enthusiasm and interest in participating in future similar engagement activities. They commented that ‘the process generated a great level of interaction and engagement, and a strong sense of community connection’.

The MSM focus group commented that four group discussions were too few, and more discussions should be arranged to facilitate formation of a better rapport within the group and in-depth information sharing. MSM co-creators appreciated time given before each discussion to allow them to prepare for each task. MSM co-creators requested regular feedback from the project team about how their ideas would be incorporated into and influence the subsequent intervention, suggesting a need for greater accountability.

Discussion

We present our experience using co-creation to adapt and implement a gonorrhea and chlamydia testing service for Chinese men. Our paper extends the literature by describing our four-stage, iterative, structured approach to co-creation and evaluating the co-creation experience. Our results highlight three principal findings: (1) the importance of community leadership in strengthening ownership and inclusivity, (2) community members’ enthusiasm and motivation for co-creative tasks, and (3) strategies to improve co-creation with marginalized communities in low- and middle-income settings.

First, designating appropriate community leadership can help create ownership and promote inclusivity during the co-creation process. Selecting a well-respected MSM as one of our facilitators greatly contributed to creating a safe, welcoming atmosphere, and seemed to indicate to many co-creators that we were sincere about their ownership, so community members were willing to openly share their sexual health issues and needs. This suggests the importance of the needs assessment and preparation phases of co-creation in understanding the community’s preferences and selecting an appropriate leader before even beginning to hold meetings. Although co-creation has long been recognized as a collaboration with researchers and community, previous literature showed concern that this process can sometimes be dominated by academics, which may weaken the community’s role and participation, and fail to generate community-led outcomes.21,22 We successfully involved community leadership from the beginning to mitigate these issues and strengthen community ownership.

Second, our co-creators demonstrated their enthusiasm, diligence and engagement throughout the process, often demanding increased accountability. Increasingly, experts in public health call for the voice of community in participating in public health decision-making.3,23,24 Our co-creators requested the project team to regularly report to the co-creation group about how their inputs influence the intervention and implementation, and many reported interest in future co-creation and even implementing this intervention. Our evaluation data also show co-creators’ high satisfaction and their willingness to adapt the intervention. Most co-creators’ participations were active, and their performance in taking initiative and demanding a stronger role showed a positive response to the shared leadership described in the community engagement continuum.1 Such partnerships have potential for long-term, sustainable, public health interventions led by communities.

Finally, this paper presents our strategies for working with vulnerable and marginalized populations in resource-limited settings. Previous co-creation and community research has shown the challenges of working with vulnerable groups as many are structurally invisible25 and fear exposing themselves to researchers, making it difficult for researchers to build rapport with vulnerable groups.26,27 Our co-creation therefore developed effective approaches to mitigate some of the above issues. In terms of recruitment strategy, we started with an open recruitment process, inviting co-creators to participate, as well as a convenience sampling in our immediate MSM community, targeting those who we knew were highly engaged in their communities to ensure adequate participation in co-creation. Moreover, our hybrid format of co-creation process allowed both MSM who were more comfortable about being out to others, and men who preferred to stay closeted. This is primarily because closeted MSM may have concerns or feel anxious about outing to strangers, and such distress can be eliminated via anonymous online participation.28 Recruiting MSM who had not widely disclosed their sexual orientation was a priority, because they are often underserved, and may be at higher risk for HIV and other STDs.29

This study had several limitations. First, we reported data from one co-creation project convened in a single location focusing on one community, and may not necessarily be applicable to co-creation processes in other locations on other topics, with other communities. However, we collected rich data regarding the Chinese MSM community’s sexual health needs through eight co-creation meetings. We also conducted co-creation evaluation through surveys and open-ended questions to increase our data’s richness, which provides significant detail and summary on our co-creation process. Second, as previously discussed, there was selection bias in choosing our co-creators; in general, our co-creators tended to be well-educated and young, which may have biased our co-creation process. Despite an open recruitment for MSM end users, our participant recruitment strategies still risked insufficient representation of the community.

Third, we observed some power imbalance among co-creators during the co-creation process. Despite our efforts to maintain that all co-creators were equal, this resulted in dominance of the conversation by physicians and MSM community leaders over others. We later mitigated this by holding co-creation meetings with only MSM community, and emphasized this issue during the later sessions. Fourth, we admit that not all co-created ideas and contents were included in the intervention, and some needed to compromise due to the limited availability of resources in the public clinic and CBO settings. However, we documented these ideas, so that they may be incorporated in the future.

Overall, this report of our experience can help inform future co-creation processes for public health interventions and implementation strategies. A previous review30 suggested that many so called ‘co-creation’ activities generated limited community engagement at a tokenistic level and there is a lack of practical consensus to organize co-creation in a structured way. Our description detailed the organization process and provided an empirical example of co-creating with a vulnerable population on a sensitive topic in low- and middle-income settings. Our co-creation experiences may also have practical implications for public health practitioners and campaign designers interested in deepening community ownership and engagement.

Conclusion

We successfully adapted a four-stage co-creation process to adapt and implement a sexual health testing service among MSM in China for community-led and public clinics. This approach effectively enhanced community leadership and fostered a sense of ownership, and resulted in practical, useful adaptations and implementation strategies. Our co-creation experience may prove beneficial for engaging other underserved and marginalized populations in low- and middle-income settings.

Data availability

All relevant data have been published in the manuscript. Further details can be obtained by writing to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

JDT is the co-Editor-in-Chief of Sexual Health, DW and WT are Associate Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest, they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This project is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (grant number NIH NIAID R01AI158826), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 82473742, 82304257), and Career Development Fund at Nanjing Medical University (NMUR20230008). The funders played no role in the study design, implementation, data collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author contributions

DW, JDT and RR conceived the idea. DW, WT and DL organized the co-creation events. RKJT and GM observed and reflected on the co-creation process. WT, RR and JDT provided constructive guidance and feedback to the process and manuscript writing. DW wrote the initial draft, LZ and KTL extensively revised the paper based on reviewer comments, and other authors commented and edited the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all co-creation members and stakeholders who have contributed to the process.

References

1 US Department of Health and Human Services. Principles of community engagement. 2nd edn. 2015. Available at https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf [accessed 20 August 2018]

2 O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 129.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Thomas JC, Sage M, Dillenberg J, Guillory VJ. A code of ethics for public health. Am J Public Health 2002; 92(7): 1057-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Salsberg J, Parry D, Pluye P, Macridis S, Herbert CP, Macaulay AC. Successful strategies to engage research partners for translating evidence into action in community health: a critical review. J Environ Public Health 2015; 2015: 191856.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Zhao Y, Fitzpatrick T, Wan B, Day S, Mathews A, Tucker JD. Forming and implementing community advisory boards in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20(1): 73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst 2020; 18(1): 17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Ní Shé É, Harrison R. Mitigating unintended consequences of co-design in health care. Health Expect 2021; 24(5): 1551-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Allender S. Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health – a perspective on definitions and distinctions. Public Health Res Pract 2022; 32(2): e3222211.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Sanders EB-N, Stappers PJ. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008; 4(1): 5-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Li C, Zhao P, Tan RKJ, Wu D. Community engagement tools in HIV/STI prevention research. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2024; 37(1): 53-62.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Louise L, Annette B. Drawing straight lines along blurred boundaries: qualitative research, patient and public involvement in medical research, co-production and co-design. Evid Policy 2019; 15(3): 409-21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Dietrich T, Trischler J, Schuster L, Rundle-Thiele S. Co-designing services with vulnerable consumers. J Serv Theory Pract 2017; 27(3): 663-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Li KT, Tang W, Wu D, et al. Pay-it-forward strategy to enhance uptake of dual gonorrhea and chlamydia testing among men who have sex with men in China: a pragmatic, quasi-experimental study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 76-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Yang F, Zhang TP, Tang W, et al. Pay-it-forward gonorrhoea and chlamydia testing among men who have sex with men in China: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20(8): 976-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Leask CF, Sandlund M, Skelton DA, et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res Involv Engagem 2019; 5(1): 2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Trischler J, Dietrich T, Rundle-Thiele S. Co-design: from expert- to user-driven ideas in public service design. Public Manag Rev 2019; 21(11): 1595-619.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Galabo R, Cruickshank L. Making it better together: a framework for improving creative engagement tools. CoDesign 2022; 18(4): 503-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Marley G, Tan RKJ, Wu D, et al. Pay-it-forward gonorrhea and chlamydia testing among men who have sex with men and male STD patients in China: the PIONEER pragmatic, cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1): 1182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Darroch F, Giles A. Decolonizing health research: community-based participatory research and postcolonial feminist theory. Can J Action Res 2014; 15(3): 22-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Wallerstein N, Muhammad M, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Power dynamics in community-based participatory research: a multiple-case study analysis of partnering contexts, histories, and practices. Health Educ Behav 2019; 46(1_suppl): 19S-32S.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010; 100(S1): S40-S6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Mulvale G, Robert G. Special issue- engaging vulnerable populations in the co-production of public services. Int J Public Adm 2021; 44(9): 711-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Lesser J, Oscós-Sánchez MA. Community-academic research partnerships with vulnerable populations. Annu Rev Nurs Res 2007; 25(1): 317-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Bernays S, Lanyon C, Tumwesige E, et al. ‘This is what is going to help me’: developing a co-designed and theoretically informed harm reduction intervention for mobile youth in South Africa and Uganda. Glob Public Health 2023; 18(1): 1953105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Tan RKJ, Wu D, Day S, et al. Digital approaches to enhancing community engagement in clinical trials. npj Digit Med 2022; 5(1): 37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Visscher BR, Fahey JL. Accelerated course of human immunodeficiency virus infection in gay men who conceal their homosexual identity. Psychosom Med 1996; 58(3): 219-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |