Attitudes towards models of abortion care in sexual and reproductive health: perspectives of Australian health professionals

Nicola Sheeran A * , Liz Jones B , Bonney Corbin C and Catriona Melville DA

B

C

D

Abstract

Abortion care is typically undertaken by doctors; however, alternate models, including nurse-led care, are increasingly seen as viable alternatives. However, attitudes towards the leadership of alternate models can be a barrier to change. We explored the acceptability of different models of abortion care, and whether attitudes differed by health profession for those working in sexual and reproductive health.

Our mixed method survey explored how doctors, nurses/midwives and those working in administrative roles in primary care in Australia felt about three models of abortion care: doctor-led, nurse-led and self-administered. ANOVAs compared favourability ratings and attitude strength across groups, and qualitative data exploring how they felt about each model was thematically analysed using Leximancer.

Attitudes towards doctor-led and nurse-led models of care were overwhelmingly positive. However, doctors perceived doctor-led care more favourably than other professionals, and felt it provides a more holistic, safer experience, that opportunistically facilitated discussions about other sexual and reproductive health matters. Self-administered care was perceived unfavourably by ~60% of participants, and was associated with significant safety concerns.

Most health professionals working in sexual and reproductive health care perceive that nurse-led models of care are viable and acceptable, although doctors feel there are additional benefits to the current model. Self-administered abortion is overwhelmingly perceived as unsafe. Nurse-led care models could increase access to safe abortion in Australia, and are perceived favourably by those working in sexual and reproductive health care.

Keywords: abortion care, attitudes, doctors, health professionals, nurse-led care, nurses, reproductive health, self-administered abortion, sexual health.

Introduction

Changes to service delivery in the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) sector have been proposed many times by academics and those working in SRH globally to address barriers to early abortion access, such as the lack of appropriately trained abortion providers (Sharma and Guthrie 2006; Culwell and Hurwitz 2013; Mainey et al. 2020). Abortion care is typically led by a doctor: usually an obstetrician and gynaecologist or general practitioner (GP); however, several models of nurse-led care have been proposed both in Australia (de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019) and in the UK (Sheldon and Fletcher 2017) to increase access to abortion services, while maintaining high levels of safety and efficacy. Limitations to implementing nurse-led models of care include a lack of training, lack of funding, and current regulations and legislation (Moulton et al. 2021). Additionally, the rate of self-managed abortions is increasing, with medications obtained online (Aiken et al. 2018), although little is known about this practice in Australia (de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019). Our research aimed to explore Australian health professionals’ perceptions of models of service delivery. Specifically, we were interested in health professionals working in SRH care’s attitudes towards nurse-led care and self-administered abortion care. We were also interested in whether different groups of health professionals (i.e. doctors and nurses) held differing attitudes towards the various models.

Abortions performed earlier in pregnancy are safer than those performed at later gestations, as complications increase with increasing gestational age of the pregnancy (RCOG 2004). A globally recognised strategy to improve access and address the shortage of abortion providers is to enlist nurses and or midwives. Research supports safe, effective provision of early medical abortion by these other clinicians (Barnard et al. 2015; WHO 2015). Currently in Australia, medication abortion can be accessed via telemedicine and in-person/in-clinic care, and is delivered by a range of services, such as non-government organisations and primary care (GP’s, family planning, etc.). Additionally, some practices offer nurse-facilitated provision with GP oversight until 63 days’ gestation (de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019). Surgical abortion is also available, with some arguing that nurses could also provide manual vacuum aspiration abortions safely (Sheldon and Fletcher 2017). Although barriers to completely nurse-led care are regularly under review, such as the 2023 regulatory changes that enabled nurses to access medical abortion training and become prescribers, or jurisdictional legislative changes (i.e. Queensland) that reduce risk of nurse prescribers being criminalised (Queensland Government 2023), many other legislative and regulatory requirements continue to render nurse-led models unfeasible.

One factor influencing public and organisational policy decisions regarding models of care, and hence the services available, is the attitudes of key stakeholders, such as health professionals. Attitudes towards nurse-led abortion care tend to be mixed. For example, de Moel-Mandel et al. (2019) found that a panel of physicians, nurses and experts provided overall support for a nurse-led model of medical abortion in Australia (75%), but only 58% of respondents felt that nurses should be allowed to solely manage the entire abortion process. Desai et al. (2022) found that 62.3% of nurses and midwives who responded to their Queensland-based survey believed that specialist doctors and GPs should provide abortion care, compared with 35.5% believing that abortion provision should be within the scope of nurses. However, in the US, across states, 31–65% of nurse-midwives supported nurse-led models. Less is known about attitudes toward self-administered abortion, with qualitative studies suggesting ~50% of abortion providers perceive self-administered abortions as unsafe (Kerestes et al. 2019a). These mixed attitudes and the lack of consensus from the key providers of abortion create barriers to change at a legislative, educational and practical level (Mainey et al. 2020). Similarly, attitudes about abortion generally tend to be quite strongly held, making changes to legislation often difficult and untimely (Arisi 2003).

One factor influencing whether an attitude will change is the strength with which it is held. Stronger attitudes tend to be more stable over time, resistant to change, crystallised, and impact information processing and behaviour, compared with weak attitudes (Krosnick and Abelson 1992; Krosnick et al. 1994; Haddock and Maio 2009). Although there are many components of attitude strength, the current study measured attitude ambivalence. Attitude ambivalence is defined as the ‘simultaneous endorsement of both favourable and unfavourable positions’ (Haddock and Maio 2009, p. 77), and research suggests that highly ambivalent attitudes are more susceptible to change (Armitage and Conner 2000).

The current study

A small number of studies (de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019; Kerestes et al. 2019a; Desai et al. 2022) have explored attitudes towards different models of abortion care. However, no studies have considered whether different groups of professionals hold different attitudes towards the models of care, nor whether they differ in terms of attitude strength. We aimed to ascertain the acceptability of different models of abortion care and whether attitudes differed by profession.

Method

Participants

A total of 69 of approximately 250 eligible health professional’s working at MSI Australia commenced the study (27.6% response rate). Of the 69 participants, 15 provided only demographic data, resulting in a final sample of 54 participants. Analyses showed there were no significant demographic differences between completers and non-completers. Three groups of participants were created: doctors (e.g. GPs and obstetricians and gynaecologists; n = 12); nurses and midwives (n = 26); and staff in administrative roles (e.g. medical receptionist, health economist, national call centre, coordinator; n = 15). The mean age was 39.09 years (s.d. 10.85 years; range 19–58 years). Most identified as women (n = 47; 87%), followed by men (n = 5) and trans/non-binary (n = 1). Most identified as white (n = 49; 90.7%) and had worked in the profession for 11.09 years on average (s.d. 10.45 years; range 0.5–39 years). Most were employed full-time (n = 26; 48.1%), with others employed part-time (n = 17; 31.5%) or casual contract (n = 11; 20.4%).

Materials

Participants rated their favourability towards doctor-led abortion care, nurse-led abortion care and self-administered abortion care on a single item created for this study. Single-item measures of attitudes are commonly used, and have been found to be as reliable and valid as longer attitudinal measures (Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007). Participants rated how they felt about each model on a scale from 1 (extremely unfavourable) to 100 (extremely favourable), with 50 indicating neutral attitudes.

Attitude strength was measured with two questions assessing attitude ambivalence (Visser and Mirabile 2004). The items asked how conflicted participants felt about the issue and to what extent they had mixed feelings about each of the models of care, and were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from: 1= ‘Not at all’ to 5= ‘Completely’.

Procedure and setting

MSI Australia is the largest provider of SRH in Australia. Health professionals employed by MSI Australia were invited to participate in an online survey (hosted on Redcap) between May 2020 and October 2021. To increase participation of those without access to a computer in the workplace, hard copy versions of the survey were provided to clinics in 2021. Ethical approval for the study was granted by Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (ref no: 2020/333). All participants provided informed consent by completing the consent form (either electronically or returning a hard copy).

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were entered into SPSS version 28. The three favourability ratings had missing data (doctor-led 11%, n = 6; nurse-led 13%, n = 7; self-administered 22%, n = 11). Little’s MCAR test indicated that data were missing completely at random; therefore, to maintain sample size and reduce the risk of bias, missing data were replaced by the expectation–maximisation technique, which is the recommended method of managing missing data in these circumstances (Dong and Peng 2013). Due to our sample size, we were not able to conduct factorial ANOVAs to test the interaction between attitudes by professional group and the three models of care. Instead, two separate sets of analyses were conducted. The first set of three repeated measures ANOVAs assessed whether attitudes and attitude strength differed towards the three models of care. In the second set of analyses, three one-way ANOVAs were conducted for each of the measures of attitudes to test whether the three professions held differing attitudes towards each of the three models of care.

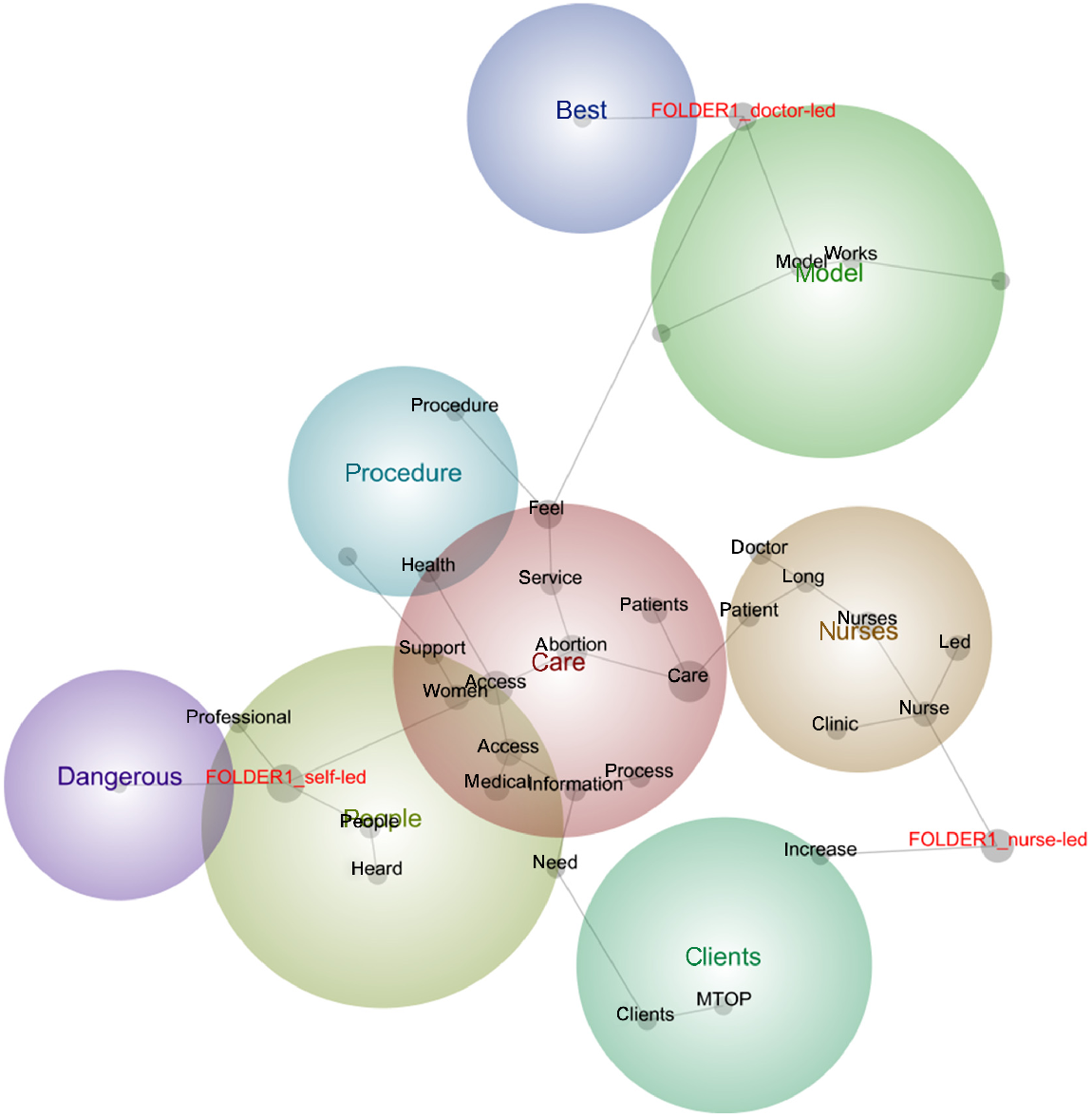

Responses to the open-ended questions were analysed using Leximancer version 4.5, a text-mining software package that performs an automated lexical analysis that maps the presence, frequency and co-occurrence of the key concepts for each of the models of care (Smith and Humphreys 2006). Meaningful relationships among concepts are extracted using artificial intelligence that considers concept frequency and co-occurrence data, to compile a co-occurrence matrix, and a statistical algorithm to create a two-dimensional map. As Leximancer derives concepts solely based on co-occurrence in text, it is less interpretive than researcher-driven coding (Smith and Humphreys 2006). The Leximancer concept map presents the main concepts derived from the text and their relative importance, as well as the strength of links or co-occurrence (Smith and Humphreys 2006). Concepts are automatically grouped into themes by Leximancer, and those mentioned together tend to lie near one another (Smith and Humphreys 2006). The size of each concept’s point indicates its centrality to the theme, and the relative position to the folder label indicates its relationship to that model.

Results

Percentages of those reporting favourable, unfavourable, and neutral attitudes were calculated and are shown in Table 1. Both nurse-led and doctor-led models of care were perceived favourably, whereas self-administered care was generally perceived unfavourably.

| Nurse/midwife (%) | Doctor (%) | Administrative staff (%) | Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor-led | |||||

| Favourable | 61.6 | 100 | 86.7 | 75.9 | |

| Neutral | 19.2 | – | – | 11.1 | |

| Unfavourable | 19.2 | – | 13.3 | 13 | |

| Nurse-led | |||||

| Favourable | 73.1 | 75 | 100 | 77.7 | |

| Neutral | 7.7 | 8.3 | – | 7.5 | |

| Unfavourable | 19.2 | 16.7 | – | 14.8 | |

| Self-administered | |||||

| Favourable | 61.5 | 16.7 | 40 | 31.5 | |

| Neutral | 3.8 | 8.3 | – | 3.7 | |

| Unfavourable | 34.7 | 75 | 60 | 64.8 | |

Rating: >50, favourable attitudes; 50, neutral; <50, unfavourable attitudes.

Three repeated measures ANOVAs assessed whether attitudes differed towards doctor-led, nurse-led and self-administered care. There were significant differences in how favourably the three models of care were viewed (F(1, 53) = 38.32, p < 0.001, ). Post hoc analyses showed that doctor-led care was viewed significantly more favourably than self-administered care (p < 0.001), but not nurse-led care (p = 0.276). Nurse-led care was viewed significantly more favourably than self-administered care (p < 0.001). Means are shown in Table 2.

| Nurse/ midwife M (SD) | Doctor M (SD) | Administrative staff M (SD) | Total M (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor-led care | |||||

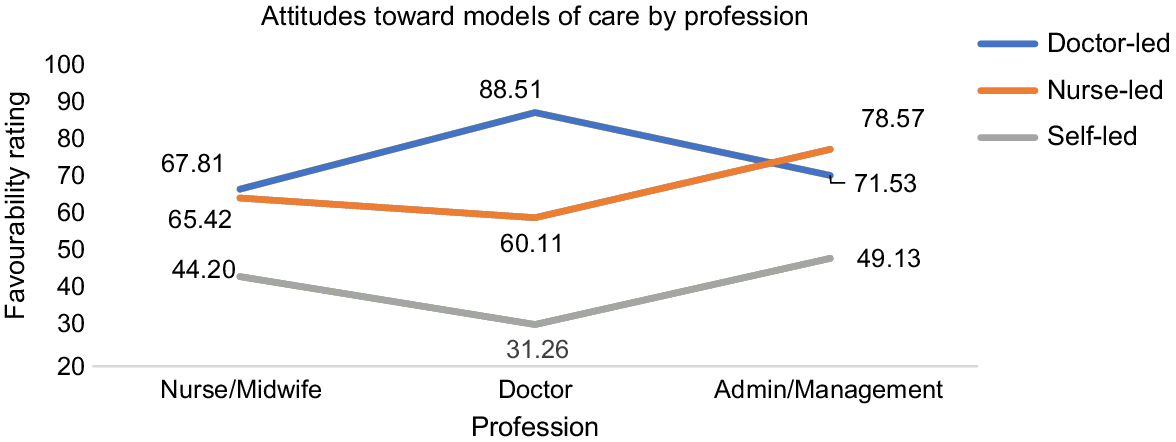

| FavourabilityA | 67.81 (22.08)b | 88.51 (12.06)a | 71.53 (16.49)ab | 73.51* (20.31) | |

| ConflictedB | 1.50 (0.95)ab | 1.00 (0.00)a | 1.88 (0.96)b | 1.50* (0.89) | |

| Mixed feelingsC | 1.62 (1.02) | 1.08 (0.29) | 1.75 (0.68) | 1.54* (0.84) | |

| Nurse-led care | |||||

| Favourability | 65.42 (27.92) | 60.11 (24.11) | 78.57 (16.31) | 68.14* (24.79) | |

| Conflicted | 2.15 (1.19) | 2.25 (1.29) | 1.60 (0.63) | 2.02# (1.09) | |

| Mixed feelings | 2.04 (1.28) | 2.33 (1.15) | 1.67 (0.72) | 2.02# (1.12) | |

| Self-administered | |||||

| Favourability | 44.20 (30.18) | 31.26 (24.65) | 49.13 (27.46) | 42.78# (28.50) | |

| Conflicted | 3.13 (1.33)ab | 3.67 (1.30)a | 2.47 (1.36)b | 3.06^ (1.36) | |

| Mixed feelings | 2.96 (1.29)ab | 3.33 (1.43)a | 2.07 (1.10)b | 2.78^ (1.33) | |

Means with the same lowercase letter are not significantly different to each other at p < 0.05. Total means with the same symbol are not significantly different to each other at the p < 0.05.

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

There were significant differences between how conflicted participants felt about the three models of care (F(1, 50) = 38.55, p < 0.001, ). Post hoc analyses showed that participants were significantly less conflicted about doctor-led care than nurse-led care (p = 0.019) and self-administered care (p < 0.001). Participants also felt significantly less conflicted about nurse-led care than self-administered care (p < 0.001).

Finally, there were significant differences in whether participants held mixed feelings about the three models of care (F(1, 50) = 28.850, p < 0.001, ). Post hoc analyses showed that participants had significantly less mixed feelings about doctor-led care than nurse-led care (p = 0.031) and self-administered care (p < 0.001). Participants also had significantly less mixed feelings about nurse-led care than self-administered care (p = 0.001).

The professions significantly differed on how favourably they viewed doctor-led models of care (F(1, 2) = 5.146, p = 0.009). Post hoc analyses showed that doctors held more favourable views of doctor-led models of care than nurses (p = 0.005). The comparison between doctors and administrative staff was approaching significance (p = 0.064), suggesting doctors hold marginally more favourable views of doctor-led care than administrative staff. Nurses and administrative staff were not significantly different in how favourably they viewed doctor-led care (p = 1.00). Means are shown in Table 2 and presented in Fig. 1.

There were no significant differences between the three professions in how favourably they viewed nurse-led models of care (F(1, 2) = 2.310, p = 0.110), and self-administered models of care (F(1, 2) = 1.432, p = 0.248).

Three one-way ANOVAs were conducted to test whether the three professions differed in how conflicted they felt about each of the three models of care. The professions significantly differed on how conflicted they felt about doctor-led care (F(1, 2) = 3.693, p = 0.032). Post hoc analyses showed that doctors held less conflicted views of doctor-led models of care than administrative staff (p = 0.027), but not nurses (p = 0.286). Nurses and administrative staff were also not significantly different in how conflicted they were about doctor-led care (p = 0.503).

The three professions did not differ on how conflicted they felt about nurse-led care and self-administered care (F(1, 2) = 1.545, p = 0.223 and F(1, 2) = 2.752, p = 0.074, respectively), although the latter was approaching significance. Post hoc comparisons suggest that doctors held marginally more conflicted views of self-administered care than administrative staff (p = 0.074), but not nursing staff (p = 0.776). Nurses and administrative staff were also not significantly different in how conflicted they were about self-administered care (p = 0.444).

Three one-way ANOVAs were conducted to test for differences between the three professions in whether they had mixed feelings about the three models of care. There were no significant differences between the professions on the degree to which they had mixed feelings about doctor-led care (F(1, 2) = 2.511, p = 0.091) and nurse-led care (F(1, 2) = 0.929, p = 0.0402).

The one-way ANOVA for the self-administered model of care was significant (F(1, 2) = 3.491, p = 0.038). Post hoc analyses showed that doctors had significantly more mixed feelings about self-administered abortion care than administrative staff (p = 0.049), but not nurses (p = 1.00). Nurses and administrative staff were also not significantly different (p = 0.150).

Qualitative findings

We discuss below the concepts identified by the Leximancer analysis for each of the models of care (see Fig. 2). Key concepts are displayed as coloured circles, and relationships between the concepts/co-occurring words are connected by lines. Exemplar quotes that relate to each of the concepts are presented.

The predominant concept pertaining to doctor-led care was that it was the best model of care (see Fig. 2). Participants stated doctor-led care was the ‘gold standard’ (P41, nurse) and ‘best practice’ (P51, doctor) model of care for patients, with most stating it was fine or good and worked well, ‘Good model, but there is capacity for follow up by nurses … Provision of TOPs should be performed by Drs’ (P25, doctor). Participants provided several reasons why it was best, but, essentially, they felt it worked. Doctor-led care was considered comprehensive care, where patients not only received care pertaining to their abortion, but also contraception and their health in general. This viewpoint was particularly endorsed by doctors. For example, P83 (doctor) stated, ‘I feel [doctor-led care is] a vital service and gave [sic] women a face-to-face opportunity to discuss her options and consider contraception at the same visit’, while P62 (doctor) noted, ‘I am able to discuss in depth every aspect of abortion and sexual health/contraception … I have an in-depth knowledge of all aspects of women’s health care.’

Several participants also claimed this model was the safest model for patients, ‘This is safest model’ (P64, nurse). For some, there was a sense this was the way things were done; that the ‘status quo’ was being maintained for the doctors (P27, nurse). Others associated medical procedures with doctors, ‘Abortion is a medical procedure; therefore, it should be doctor led’ (P23, doctor).

Several participants described doctor-led care as a holistic model or ‘community-based approach’ (P86, admin), where health professionals, such as nurses and social workers, had significant roles, and the doctor’s role was clearly delineated within the team (i.e. prescribing). They disagreed that the predominant model was doctor led; ‘I don’t really agree that this was the case for many abortions … The Drs may prescribe and complete a procedure, but I don’t consider this to be ‘led’ by Dr’ (P66, nurse), although definitions of what constitutes care may differ, ‘… I believe it has always been an integrated model, as doctors have very little input into bookings or client calls until the situation has been presented to the doctors’ (P16, doctor).

Several comments were made about the resources/staffing required to offer doctor-led care, ‘I feel it certainly has its place, but can become limited due to unavailability’ (P49, nurse). There was also a concern expressed by some participants that this model of care was not the best use of a doctor’s time and expertise, ‘This has always been acceptable, but problematic with skilled GPs or proceduralist availability. Limited precare/consultation and phone when follow-up appointments were required’ (P65, nurse). Others directly called the model into question, ‘… The [doctor-] led model showed little respect for the role of the registered nurses and midwives. There has been little encouragement and value placed on those showing initiative and developing/maintaining skills within their scope of practice’ (P27, nurse).

Central to the nurse-led care model were concepts of clients, care and access, with medical abortions most commonly mentioned. Most participants felt nurse-led models of care were appropriate and acceptable, with nurse-led clinics seen as the ‘future’ of abortion care (P26, nurse), ‘… I would like to see a nurse practitioner lead in the clinic, driving medical terminations. This would expand on service delivery and allow clients to have better access to care’ (P49, nurse). Provision of abortion was considered well within the scope of practice for nurses. Many participants specified that for this model to be acceptable, nurses needed appropriate training, education and experience. Others specified this model was acceptable for low-risk, uncomplicated care and MTOPS, but not for procedures such as vacuum aspiration, ‘Nurse-led care is appropriate where there is adequate and specialised training in abortion is provided in low-risk cases’ (P62, doctor). For others, nurse-led models were only appropriate when doctor-led care was not feasible, ‘suitable for medical abortion in remote areas where no doctor is readily available’ (P81, doctor).

Advantages of this model were increased accessibility and decreased wait times, while also diversifying the workload for nurses, ‘… helps to give our nurses a more diverse work routine, which in turn improves their satisfaction with the role’ (P12, nurse). One doctor also noted ‘Anything that make abortion care more accessible is a good thing’ (P82). Others felt that nurse-led models provided a better patient experience, ‘patient feedback is usually centred around the nurses, who generally receive rave reviews! … Patients may report feeling rushed and unsure of doctor-led information, but do not seem to feel this from the nurses. Patients report feeling supported by the nurses, so again, nurse-led care seems like a positive change when looked at from a patient’s perspective’ (P20, admin).

However, some concerns were raised regarding increased responsibility, workload and pressure on nurses, ‘A step forward to nurses and nurse practitioner opportunities, however, did increase duties/responsibilities, which can be difficult to resource’ (P65, nurse).

The self-administered model of care received mixed feedback, and was associated strongly with the concept of danger, ‘Doesn’t sound good. Dangerous. There’s a reason we have nurses and doctors. It’s HEALTH CARE’ (P74, admin), and not to be encouraged, ‘Where there is ready access to abortion care supported by trained healthcare practitioners, I don’t feel it is best practice or to be encouraged’ (P82, doctor). Others noted feeling ‘scared’ (P58, nurse), with concerns raised about patient health literacy, access to appropriate aftercare and the person not having support, ‘Self-administered abortion care is dangerous due to low health literacy with regard to reproductive health and high stigma regarding abortion, leading to misinterpretation, misuse and delays in seeking emergency care’ (P12, nurse).

Some felt it might be appropriate for some women, whereas others felt it was never appropriate, ‘It is not appropriate, as many women have no realistic concept of their gestation or risks’ (P16, doctor). ‘I believe there should be medical input for abortion care always given the risk of ectopic, incorrect administration, what to do with excessive bleeding/pain etc.’ (P31, doctor). Approximately half of the doctors who participated felt this model resulted in missed opportunities to provide comprehensive care, ‘I worry women may not have an appropriate health check, and also contact with a health professional is often a good time to perform some health screening and contraceptive counselling’ (P25, doctor). Others noted this model might be possible, with appropriate checks and balances, ‘I wouldn’t be opposed. Most important is that people self-administering have access to clear, easy to understand information about the process, ideally in a language of their choice; as well as a clear path to seeking assistance for any questions or complications’ (P82, doctor), and in circumstances where other models of care were not available, ‘women should definitely have the choice to self-administration in circumstance where doctor-led or nurse-led care is not possible’ (P41, nurse).

Those in favour of self-administered abortion highlighted the importance of this model in facilitating timely access to an abortion, ‘This needs to be the reality for all clients accessing early and timely intervention in unplanned pregnancy. Most women and pregnant people are able to manage this process with adequate support and education. It is an essential service and needs to be more accessible’ (P27, nurse). Others saw self-abortion as part of a woman’s choice, enabling autonomy, and empowering women. ‘Totally for it with appropriate support and education. Creates a space which is empowering women and pregnant people to access choice and autonomy of care’ (P45, admin).

Discussion

Our study aimed to examine the acceptability of different models of abortion care, and whether attitudes towards the different models of care differed by profession. We found that both doctor-led and nurse-led models of care were both perceived favourably, with >80% of participants perceiving a nurse-led model favourably. However, self-administered care was perceived unfavourably by ~60% of participants, and associated with significant safety concerns. Participants were most conflicted and had more mixed feelings about self-administered care, followed by nurse-led models, and least ambivalence around doctor-led care.

Regarding differences in attitudes by the three professions, we found that doctors perceived doctor-led care more favourably than nurses, and doctors had less ambivalence around their preference for doctor-led care than administrative staff. Qualitative findings suggested doctors believed doctor-led care provided those seeking abortion care with a more holistic experience, that opportunistically facilitated discussions about other sexual and reproductive health matters. Consistent with de Moel-Mandel’s study (de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019), we found that ~75% of doctors and nurses reported favourable attitudes towards nurse-led care, and the model was perceived as key to providing timely and accessible abortion care. It was also seen as an opportunity to diversify the workload for nursing staff, although several concerns were raised regarding the need for training, support and whether the workforce would manage the additional pressure/responsibility. The proportion of those with favourable attitudes is significantly higher than the levels of acceptability found by Desai et al. (2022) in their Queensland study, perhaps suggesting that attitudes held nationally are more favourable than those in Queensland. Conversely, it may be that those working in sexual and reproductive health, where nurse-facilitated care is common, hold more favourable attitudes than Desai’s broader sample.

Approximately 60% of our nurses reported somewhat favourable attitudes towards self-administered abortion compared with only 16% of doctors. Interestingly, attitudes for administrative staff were split roughly 60:40 and mostly unfavourable. To our knowledge, no other research has compared attitudes towards self-administered abortion across health professionals. However, qualitative studies from the US suggest that 50% of health professionals perceive self-administered abortion as unsafe (Kerestes et al. 2019b), with a tension between safety and promoting patient autonomy (Baldwin et al. 2022). This is consistent with our qualitative findings, but not emerging evidence on the efficacy of self-administered medical abortions, which ranges from 75 to 99.5% efficacy (Moseson et al. 2020). Although our findings suggest low overall rates of favourability, we also found high levels of ambivalence around self-administered abortion. Research suggests ambivalent attitudes are more susceptible to change, and thus, as more research emerges on the efficacy of self-administered abortion, attitudes may become more positive.

Implications for policy, practice and future research

Our findings suggest nurse-led care is perceived positively by those working in sexual and reproductive health; particularly as an adjunct to current doctor-led models of care. Several nurse-led models of care for medical abortions have been proposed (Sheldon and Fletcher 2017; de Moel-Mandel et al. 2019). Although previous research suggests that nurse provision of vacuum aspiration for induced abortion is also safe (Sheldon and Fletcher 2017), our qualitative findings suggested medical abortions came to mind in association with nurse-led care. However, legislative and regulatory reform is needed to remove the existing barriers to enable nurse, midwifery or self-administered abortion care. In terms of legislative reform, although we have had advancements in some states, health law referencing abortion must change in every state and territory in Australia to either remove reference to which health professionals can provide care, or to include nurses and midwives in their list of options. Barriers also remain in criminal law, with nuances that criminalise nurses, midwives and other ‘unqualified persons’ from assisting in abortion access (MSI Australia 2022). Finally, drug and poisons legislation and regulations across states and territories need to be amended to enable nurse and midwifery prescribing. Until these changes are made, anyone other than doctors will continue to ‘assist’ with access to abortion, and full nurse- or midwifery-led care will not be realised.

Our findings identified concerns about nurses and midwives having sufficient training. For nurse-led care models to be practical, abortion care must be embedded in pre-service training throughout nursing and midwifery degrees. Provisions exist for conscientious objection to providing abortion, and embedding training universally ensures front-line health professionals are aware of the process, requirements for care and the referral process. In addition, professional education needs to be supported with clinical guidelines and health literacy frameworks that need to be developed.

Limitations

A key limitation of our study was the small sample size, which precluded using statistics to simultaneously compare effects of professional group and model of care. Several of our findings approached significance, and greater numbers of participants would provide greater confidence in those findings. Unfortunately, our study was undertaken when there was significant strain on the target workforce (COVID-19), which likely reduced participation rates. COVID-19 may also have impacted participants’ perceptions of abortion care. Our sample was also drawn from an organisation where nurse-facilitated care is common, with nurses/midwives undertaking most of the counselling and information sharing, and abortion aftercare.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest attitudes towards nurse-led models of abortion care are highly favourable and perceived as providing a range of positives for patients seeking an abortion. Doctors prefer doctor-led care, both because they see it as their role and because it provides opportunities for contraceptive and other sexual and reproductive health care. Self-administered care was perceived less favourably, with attitudes more ambivalent, whereby concerns about safety are weighed against patient autonomy and access. More research is needed to establish efficacy and demonstrate safety of self-administered abortion before attitude change is likely to occur.

Data availability

Data used to generate the results is not publicly available. Interested parties should contact the corresponding author.

References

Aiken ARA, Broussard K, Johnson DM, Padron E (2018) Motivations and experiences of people seeking medication abortion online in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 50, 157-163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Arisi E (2003) Changing attitudes towards abortion in Europe. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 8, 109-121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Armitage CJ, Conner M (2000) Attitudinal ambivalence: a test of three key hypotheses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26, 1421-1432.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baldwin A, Johnson DM, Broussard K, et al. (2022) U.S. Abortion care providers’ perspectives on self-managed abortion. Qualitative Health Research 32, 788-799.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Barnard S, Kim C, Park MH, Ngo TD (2015) Doctors or mid-level providers for abortion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 27, CD011242.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bergkvist L, Rossiter JR (2007) The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 44, 175-184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Culwell KR, Hurwitz M (2013) Addressing barriers to safe abortion. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 121(S1), S16-S19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

de Moel-Mandel C, Graham M, Taket A (2019) Expert consensus on a nurse-led model of medication abortion provision in regional and rural Victoria, Australia: a Delphi study. Contraception 100, 380-385.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Desai A, Maier B, James-McAlpine J, Prentice D, de Costa C (2022) Views and practice of abortion among Queensland midwives and sexual health nurses. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 62, 219-225.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dong Y, Peng C-YJ (2013) Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus 2, 222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kerestes CA, Stockdale CK, Zimmerman MB, Hardy-Fairbanks AJ (2019a) Abortion providers’ experiences and views on self-managed medication abortion: an exploratory study. Contraception 100, 160-164.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kerestes C, Sheets K, Stockdale CK, Hardy-Fairbanks AJ (2019b) Prevalence, attitudes and knowledge of misoprostol for self-induction of abortion in women presenting for abortion at Midwestern reproductive health clinics. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27, 118-125.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mainey L, O’Mullan C, Reid-Searl K, Taylor A, Baird K (2020) The role of nurses and midwives in the provision of abortion care: a scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29, 1513-1526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, Barr-Walker J, Baum SE, Gerdts C (2020) Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 63, 87-110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moulton JE, Subasinghe AK, Mazza D (2021) Practice nurse provision of early medical abortion in general practice: opportunities and limitations. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27, 427-430.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

MSI Australia (2022) Abortion law in Australia. Available at https://www.msiaustralia.org.au/abortion-law-in-australia/ [verified 03 July 2024]

Queensland Government (2023) Health and Other Legislation Amendment Bill (No. 2) 2023. Available at https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/bill.first/bill-2023-052

Sharma S, Guthrie K (2006) Nurse-led telephone consultation and outpatient local anaesthetic abortion: a pilot project. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 32(1), 19-22.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sheldon S, Fletcher J (2017) Vacuum aspiration for induced abortion could be safely and legally performed by nurses and midwives. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 43, 260-264.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Smith AE, Humphreys MS (2006) Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods 38, 262-279.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Visser PS, Mirabile RR (2004) Attitudes in the social context: the impact of social network composition on individual-level attitude strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87, 779-795.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |