A technology-enabled collaborative learning model (Project ECHO) to upskill primary care providers in best practice pain care

Simone De Morgan A * , Pippy Walker

A * , Pippy Walker  A , Fiona M. Blyth B , Anne Daly C D , Anne L. J. Burke E F G and Michael K. Nicholas H

A , Fiona M. Blyth B , Anne Daly C D , Anne L. J. Burke E F G and Michael K. Nicholas H

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Abstract

The South Australian (SA) Chronic Pain Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) Network was established to upskill primary care providers in best practice pain care aligned to a patient-centred, biopsychosocial approach using didactic and case-based virtual mentoring sessions. The aims of this study were to assess: (a) participation, satisfaction (relevance, satisfaction with format and content, perceptions of the mentorship environment), learning (perceived knowledge gain, change in attitudes), competence (self-confidence) and performance (intention to change practice, perceived practice change) of the ECHO Network clinician participants; and (b) self-perceived barriers at the clinical, service and system level to applying the learnings.

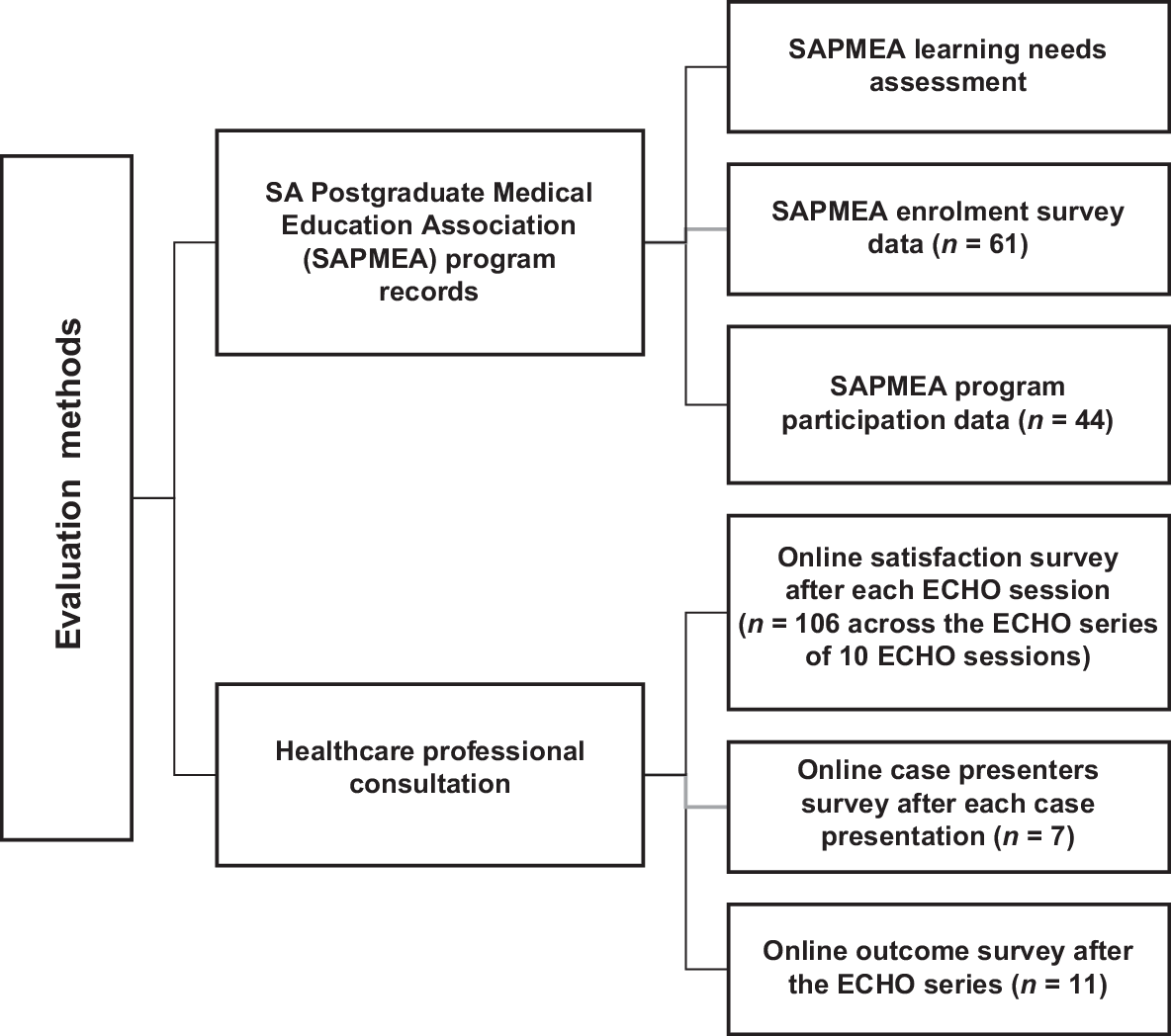

A mixed methods, participatory evaluation approach was undertaken. Data sources included analysis of program records (learning needs assessment, enrolment survey data, program participation data and online surveys of healthcare professionals including a satisfaction survey after each ECHO session (n = 106 across the ECHO series of 10 sessions; average response rate = 46%), a case presenters survey (n = 7, response rate = 78%) and an outcome survey after all 10 ECHO sessions (n = 11, response rate = 25%).

Forty-four healthcare professionals participated in the ECHO Network from a range of career stages and professional disciplines (half were general practitioners). One-third of participants practised in regional SA. Participants reported that the ECHO sessions met their learning needs (average = 99% across the series), were relevant to practice (average = 99% across the series), enabled them to learn about the multidisciplinary and biopsychosocial approach to pain care (average = 97% across the series) and provided positive mentorship (average = 96% across the series). Key learnings for participants were the importance of validating the patient experience and incorporating psychological and social approaches into pain care. More than one-third of participants (average = 42% across the series) identified barriers to applying the learnings such as limited time during a consultation and difficulty in forming a multidisciplinary team.

The ECHO Network model was found to be an acceptable and effective interdisciplinary education model for upskilling primary care providers in best practice pain care aligned to a patient-centred, biopsychosocial approach to pain managment. However, participants perceived barriers to translating this knowledge into practice at the clinical, service and system levels.

Keywords: biopsychosocial, chronic pain, education, pain management, patient-centred, primary care, Project ECHO, workforce.

Introduction

Chronic pain affects one in five people in Australia (AIHW 2020) and has a high economic burden, estimated as A$139 billion in 2018, through reduced quality of life, productivity losses and direct health system costs (Deloitte 2019).

Multidisciplinary team-based care underpinned by the biopsychosocial model of pain is considered best practice pain care (Nicholas 2022). Given the long waitlists for multidisciplinary tertiary pain services and their limited reach into regional Australia (Hogg et al. 2021), it is critical that we upskill primary care providers in best practice approaches (Australian Government Department of Health 2019; ANZCA 2023). Ensuring equity of access to pain management education is an important consideration, as many primary care providers are unable to access face-to-face training, particularly those living in regional areas (Slater et al. 2014).

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) is an evidence-based collaborative tele-education model that has been implemented in Australia and internationally to upskill healthcare professionals in a range of conditions and reduce healthcare disparities (Zhou et al. 2016; McBain et al. 2019; Moss et al. 2021). ECHO networks for chronic pain have been successfully implemented internationally (Furlan et al. 2019; Hassan et al. 2021); however, evidence in the Australian context is limited (De Morgan et al. 2021; Moss et al. 2023).

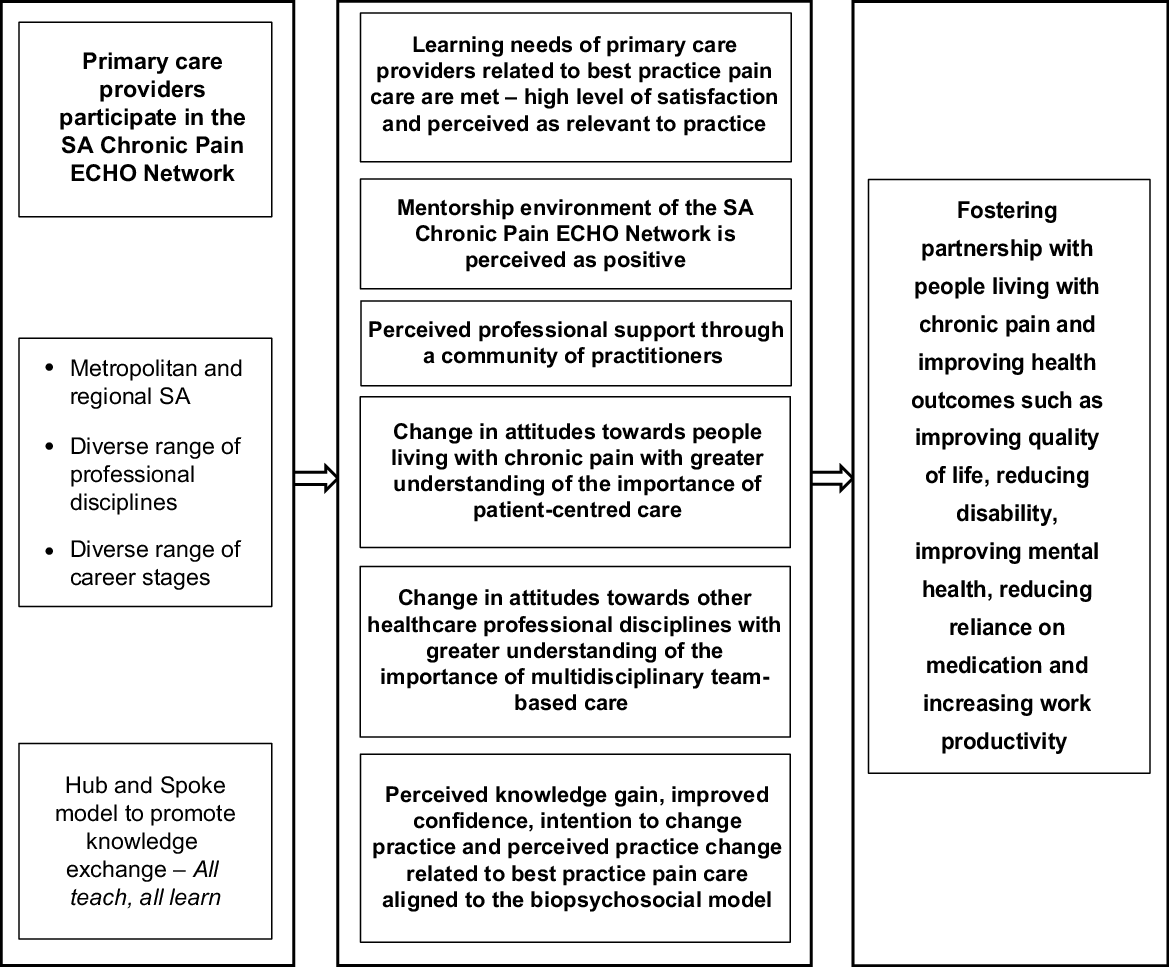

Project ECHO’s five guiding principles are: (A) Amplification: use videoconference technology to leverage scarce resources; (B) Share Best Practices: to reduce disparities; (C) Case-based learning: to master complexity and increase self-efficacy; (D) Web-based database: to monitor outcomes and showcase impact; and (E) Everyone participates: ‘all teach, all learn’ (Moss et al. 2020). Project ECHO uses a Hub and Spoke model to promote knowledge exchange between a multidisciplinary Hub team (often associated with a tertiary hospital setting) and healthcare professional spokes (often associated with the primary care setting). ECHO sessions are virtual and have two components: (1) a didactic presentation by a hub panel member; and (2) a case presentation by a spoke healthcare professional followed by group discussion and feedback by hub panel members. See Fig. 1 for the program logic of the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network.

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was established as part of the National Pain Management Education Project led by the University of Sydney and funded by the Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care (Grant GO2810; 2020–2024) to build health workforce capacity and capability in pain management and as a response to supporting implementation of the National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management. The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was implemented as part of an ECHO Hub established by the South Australian Postgraduate Medical Association (SAPMEA). The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was implemented between July and November 2022 and was not intended as an ongoing program, consistent with other ECHO programs implemented by SAPMEA, with funding provided for 10 ECHO sessions only (75 min duration) over a 20-week period (fortnightly ECHO sessions).

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was accredited with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM) for continuing professional education (CPD) points. All other healthcare professionals were able to self-claim CPD points with their respective professional associations.

Although the standard didactic and case presentation format was used for most ECHO sessions, for the last ECHO session, a case presenter was not available, and this component was replaced by a question and answer discussion. The recordings and slides from the didactic presentations and links to relevant healthcare professional and consumer resources discussed in the ECHO sessions were provided on SAPMEA’s webpage after each session.

ECHO hub panel members represented a range of professional disciplines including two specialist pain medicine physicians (shared position), a general practitioner (GP) with expertise in pain management, an Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA)-titled pain physiotherapist, and two clinical psychologists with expertise in pain management (shared position). The facilitator was a GP recruited by SAPMEA.

Refer to Table 1 for an outline of the curriculum topics. Each didactic presentation was developed by one to three hub panel members and shared with other hub panel members, the GP facilitator and the evaluation team for review and feedback to ensure that the content was based on current best practice pain care aligned to a biopsychosocial approach (NICE Guideline [NG193] 2021; Nicholas 2022). Hub panel members were also provided with the empirically-derived consumer pain care priorities framework (Listen to me, learn from me) developed by Curtin University as part of the National Pain Management Education Project to support Hub panel members to develop didactics aligned to high quality person-centred pain care.

| ECHO session 1 | Chronic pain management fundamentals – the biopsychosocial model of pain | |

| ECHO session 2 | Explaining pain to patients – language, messaging and helping reduce pain catastrophising | |

| ECHO session 3 | Psychological strategies and self-management approaches to pain management | |

| ECHO session 4 | Physical therapies and activity pacing | |

| ECHO session 5 | Types of chronic pain with a focus on neuropathic pain and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) | |

| ECHO session 6 | Low back pain | |

| ECHO session 7 | Safe and effective use of medicines for chronic pain | |

| ECHO session 8 | Strategies to support opioid tapering in people with chronic pain | |

| ECHO session 9 | Secondary prevention of chronic pain in the pre/post-surgery and post-injury phase | |

| ECHO session 10 | Sleep management | |

| Topics were selected based on a learning needs assessment of participants (via an online survey of potential participants during the expression of interest phase and via the enrolment form) and advice from the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network Advisory Group related to essential knowledge in best practice pain care. | ||

Aims of this study

Aim 1: To assess participation, satisfaction (relevance, satisfaction with format and content, perceptions of the mentorship environment), learning (perceived knowledge gain, change in attitudes), competence (self-confidence), and performance (intention to change practice, perceived practice change) of the ECHO Network clinician participants.

Aim 2: To assess the self-perceived barriers of healthcare professionals to applying the learnings at the clinical level (micro), service level (meso) and system level (macro).

Methods

Partnership approach

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network Advisory Group provided input into the planning, implementation and evaluation of the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network using participatory methods to ensure that the ECHO Network and the evaluation responded to the needs of practitioners and decision-makers and was feasible (within limited time and resources) (Chouinard and Milley 2018). The Advisory Group included representatives from The University of Sydney, SAPMEA, the SA Chronic Pain Statewide Clinical Network (Commission on Excellence and Innovation in Health) and commissioners – ReturnToWorkSA and Country SA Primary Health Network. The Advisory Group members had expertise in planning and implementing ECHO programs, evaluating ECHO programs, clinical pain management and primary health care. Regular online meetings and workshops were conducted to discuss the purpose and program logic of the ECHO program; implementation considerations; healthcare professional and key stakeholder engagement; selection of ECHO hub panel members; curriculum priorities and didactic presentations; evaluation aims, design and questions; and survey tools.

The Advisory Group recommended capping the number of enrolled participants to approximately 60 participants, assuming approximately half of participants would attend each ECHO session, to foster interactivity and a sense of belonging to a community of practice.

Theoretical frameworks

Aim 1: An Outcome Framework for Planning and Assessing Continuing Medical Education (CME), a commonly used evaluation framework for Project ECHO programs developed by Moore et al. (Moore et al. 2009; Moore et al. 2018) was used in this study. The framework includes seven outcome levels: Level 1 – participation; Level 2 – satisfaction; Level 3 – learning; Level 4 – competence; Level 5 – performance; Level 6 – patient health; and Level 7 – community health.

Aim 2: A multilevel framework developed by Ng et al. as part of a qualitative evidence synthesis of the barriers and enablers to adopting a biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal pain was used to categorise self-perceived barriers to applying the learnings from the ECHO Network at the clinical level (micro), service level (meso) and system level (macro) (Ng et al. 2021).

Data sources

Data sources included analysis of program records (learning needs assessment, enrolment survey data, program participation data) and online surveys of healthcare professionals including a satisfaction survey after each ECHO session (n = 106 across the ECHO series of 10 sessions), a case presenters survey (n = 7) and an outcome survey after all 10 ECHO sessions in the series (n = 11). Refer to Fig. 2.

Evaluation questions and survey development

The evaluation aims, evaluation questions and survey questions were developed by the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network Advisory Group. Refer to Supplementary Appendix S1 for the evaluation questions. To ensure face validity of the surveys, a clinical psychologist and an APA-titled pain physiotherapist from the Advisory Group reviewed the surveys for appropriateness, and the surveys were also piloted with two GPs. The surveys included Likert scales and open questions to allow qualitative feedback. Refer to Supplementary Appendix S2 for the online surveys.

Recruitment

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was promoted on SAPMEA’s ECHO webpage. The ECHO Network was also promoted via SAPMEA’s social media platforms (Facebook and LinkedIn), e-newsletter and a promotional flyer sent to SAPMEA’s networks and the networks of ReturnToWorkSA, Country SA Primary Health Network, Adelaide Primary Health Network, the SA Chronic Pain Statewide Clinical Network, Rural Doctors Workforce Agency, SA Pharmacy Network and SA GP Integration Units. Only South Australian healthcare professionals were eligible to participate in the ECHO Network.

Data collection

SAPMEA collected information from potential participants at enrolment including demographic data, learning needs related to the topic and interest in presenting a case. The data was de-identified by SAPMEA prior to sharing with the research team.

Qualtrics XM was used to administer the online participant satisfaction and outcome surveys. Participants received a link to the satisfaction survey embedded into each ECHO session (via the videoconferencing application) as they exited each of the 10 ECHO sessions. They were informed that the survey was voluntary and that they could ‘exit’ without completing the survey. SAPMEA emailed a survey link to healthcare professionals who had presented a case in each ECHO session (i.e. case presenters survey). After the ECHO series of 10 sessions, SAPMEA emailed a link to the outcome survey to all participants.

Data analysis

Aim 1: Survey items responding to each evaluation question were analysed quantitatively by the second author (PW) in IBM SPSS Statistics Software (Version 28) for the enrolment data and Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Software 9.4 for the online satisfaction and outcome survey data. Data from the satisfaction survey were analysed for each ECHO session and across the ECHO series to report average percentages of positive responses across the 10 sessions. A deductive thematic analysis (Miles et al. 2014) of the qualitative data (i.e. open questions in the online surveys) was undertaken with themes derived from the evaluation questions and subthemes identified by the primary author (SDM) and reviewed by the second author (PW) for validation, resolving any disagreements by discussion and consensus. Refer to Supplementary Appendix S1 for the evaluation questions and outcomes of the ECHO Network.

Aim 2: An inductive thematic analysis (Miles et al. 2014) of the qualitative data (i.e. open questions in the online surveys) related to self-perceived barriers to applying the learning was undertaken. Themes included clinical-level (micro) barriers, service-level (meso) barriers and system-level (macro) barriers (Ng et al. 2021). An inductive process with careful reading and rereading of the qualitative data by the primary author (SDM) was undertaken to identify subthemes and these were reviewed by the second author (PW) for validation, resolving any disagreements by discussion and consensus.

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network Advisory Group also provided feedback on the reporting of the evaluation to ensure accuracy and clarity. However, the commissioners (ReturnToWork SA and Country SA Primary Health Network) and the implementer organisation (SAPMEA) did not provide input into the data analysis and recommendations to ensure independence and credibility of the findings.

Results

Participation

Forty-four healthcare professionals participated in at least one ECHO session (72% of enrollees, n = 61). On average, each healthcare professional participated in 5.3 sessions. Overall, 15–33 healthcare professionals participated in each ECHO session, with participation as follows: ECHO session 1 (n = 33); ECHO sessions 2–8 (n = 22–29) and ECHO sessions 9–10 (n = 15–17).

Approximately half of participants were GPs (48%, n = 21) and half represented a range of other professional disciplines. A range of career stages were represented and one-third of healthcare professionals practised in regional SA. Case presenters (n = 9) included seven GPs, one social worker and one paramedic. Refer to Table 2 for the profile of participants in the ECHO Network.

| Number (n) | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| i. Professional disciplines | |||

| General practitioners | 21 | 48 | |

| Nurses or nurse practitioners | 7 | 16 | |

| Physiotherapists | 5 | 11 | |

| Paramedics | 3 | 7 | |

| Pharmacists | 2 | 5 | |

| Social workers | 1 | 2 | |

| Podiatrists | 1 | 2 | |

| Psychiatry registered medical officers | 1 | 2 | |

| Psychologists (general) | 1 | 2 | |

| Educational role only | 1 | 2 | |

| Chronic pain community-based program co-ordinators | 1 | 2 | |

| ii. Years in practice | |||

| >10 | 26 | 59 | |

| 6–10 | 6 | 14 | |

| 2–5 | 9 | 20 | |

| <2 | 3 | 7 | |

| iii. Number of patients with chronic pain in the past 12 months | |||

| >30 | 15 | 34 | |

| 11–30 | 14 | 32 | |

| 6–10 | 8 | 18 | |

| 1–5 | 4 | 9 | |

| None | 3 | 7 | |

| iv. Number of patients with workplace injuries managed under the worker’s compensation scheme in the past 12 months | |||

| None | 15 | 34 | |

| 1–5 | 15 | 34 | |

| 6–30 | 10 | 23 | |

| >30 | 4 | 9 | |

| v. Primary work location | |||

| Metropolitan SA | 31 | 70 | |

| Regional SA | 13 | 30 | |

| vi. Type of workplace setting | |||

| Team of practitioners from the same clinical discipline | 21 | 48 | |

| Team of practitioners from different clinical disciplines | 18 | 41 | |

| Solo practices | 5 | 11 | |

Satisfaction, learning, self-confidence and performance

Satisfaction surveys after each ECHO session: Across the ECHO series of 10 sessions, 106 satisfaction surveys were completed, with an average response rate of 46% per ECHO session (range 34–60%). Refer to Supplementary Appendix S3 for survey response rates.

A mix of professional disciplines were represented in the overall responses: GP (70%, n = 74 survey responses/106); nurse or nurse practitioner (11%, n = 12/106); pharmacist (1%, n = 1/106); physiotherapist (5%, n = 5/106); psychologist (1%, n = 1/106); paramedic (8%, n = 8/106); podiatrist (4%, n = 4/106); educational role only (1%, n = 1/106).

Final outcome survey: Eleven healthcare professionals completed the outcome survey (response rate = 25%, n = 11/44): GP (55%, n = 6); nurse or nurse practitioner (27%, n = 3); physiotherapist (9%, n = 1); psychologist (general) (9%, n = 1).

Case presenter survey: Response rate for the case presenters survey was 78% (n = 7) and included six GPs and one social worker.

The ECHO Network met the learning needs of healthcare professionals (average = 99% across the series reported ‘strongly agreeing’ or ‘agreeing’ to this item in the satisfaction survey). Similarly, the vast majority of participants reported that the ECHO Network model added value compared to other didactic education formats (average = 91% across the series), was relevant to practice (average = 99% across the series), enabled them to learn about the multidisciplinary and biopsychosocial approach to pain management (average = 97% across the series), enabled them to learn about self-management and non-pharmacological strategies to use with patients with chronic pain (average = 90% across the series), provided positive mentorship (average = 96% across the series) and professional support (average = 93% across the series).

It was incredibly validating. Huge amount of information. Very grateful to the support I have been given. (Case presenter survey)

The ECHO Network improved self-perceived knowledge and confidence to manage patients with chronic pain (outcome survey: n = 11; 100%).

The chronic pain ECHO has updated my knowledge, and it was one of the best of the ECHO series. (Healthcare professional, outcome survey)

Key learnings for healthcare professionals were the importance of incorporating psychological and social approaches into pain care, including addressing mental health issues; teaching patients psychological self-management strategies; referring to clinical psychologists if required; and promoting social connection and participation in community groups.

[Key learnings for me are] overwhelming importance of mental health in chronic pain management. (Healthcare professional, satisfaction survey)

I feel confident to ‘prescribe’ connecting with others as one of the non-pharmacological treatments for chronic pain. (Healthcare professional, outcome survey)

Participants also reported a better understanding of the importance of patient-centred care and validating the patient experience.

[Key learnings for me are] asking the patient to contribute more (i.e. listen more than talk). Make sure the patient understands clearly and reduce fear. (Healthcare professional, satisfaction survey)

Pain is invisible symptoms, so it is best to trust my patient when they are in severe pain and do my ultimate treatment. Patient care and satisfaction should be the first priority. (Healthcare professional, outcome survey)

Participants in the ECHO Network also reported improved awareness of the role of non-medical disciplines, with most GPs indicating an intention to increase referrals to allied health practitioners (outcome survey: n = 5 from 6 GPs).

[I have a] better understanding of the way in which different practitioners can contribute and work together. (Healthcare professional, outcome survey)

[I learnt the importance of the] use of physiotherapist and pain psychologist. (Healthcare professional, outcome survey)

Refer to Supplementary Appendix S1 for the evaluation questions and outcomes of the ECHO Network. Refer to Supplementary Appendix S4 for the complete data results (including number and percentages for each ECHO session) from the satisfaction survey.

Self-perceived barriers to applying the learnings

More than one-third of healthcare professionals (average = 42% across the series, satisfaction surveys) reported that there were barriers to applying the learnings from the ECHO Network. Key barriers for healthcare professionals were perceived lack of time and perceived lack of remuneration under a fee-for-service model to deliver best practice pain care aligned to a biopsychosocial approach.

Funding is a problem. Having enough time to apply biopsychosocial methods - current funding structure encourages rapid through put and discourages well-considered tailored therapies that result in less medications and less medication accidents. (Healthcare professional, satisfaction survey)

Another key barrier was the difficulty in forming a co-located multidisciplinary team within general practice. Refer to Table 3 for the self-perceived barriers to applying the learnings from the ECHO Network at the clinical level (micro), service level (meso) and system level (macro).

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotes from participants about barriers to changing practice (from the satisfaction survey after each ECHO session, n = 106 across the ECHO series; and the outcome survey after the ECHO series, n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clinical-level barriers (micro level) | i. Perceived lack of time during standard consultations to deliver best practice pain care aligned to the biopsychosocial approach | ‘Time, always short appointments, unable to allow the patient to feel comfortable to express everything.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Having enough time to apply biopsychosocial methods.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | |

| ii. Perceived patient attitudes and lack of motivation | ‘Overcoming expectations of magic bullet.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Not sure all patients are as motivated. Most want quick fixes and will not want to make any effort to help themselves.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| iii. Perceived cost barriers for patients to access multidisciplinary care | ‘Access to multidisciplinary public sector teams for low-income patients.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Lack of access to affordable physio and pain psychology.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| iv. Perceived travel barriers for patients to access multidisciplinary care, especially for regional patients | ‘It is very difficult for my patients to access a chronic pain team due to distance from team and cost of private providers.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Not all are able to travel for the MDT (multidisciplinary team) services: telehealth (is an alternative).’ (HCP, outcome survey) | ||

| v. Perceived barriers for patients with low English literacy and low health literacy to access multidisciplinary care | ‘[Lack of] access to resources especially for low literacy and low health literacy.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Interpreting services are not covered for these sessions so they rely on family which is very tenuous – lots of loss of confidentiality and redirected instructions when family is used for language provision.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| 2. Service-level barriers (meso level) | i. Lack of appropriate healthcare professional education | ‘[Lack of] funded educational programs to practitioners especially early career and recently arrived O/S (overseas) trained.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘[Lack of appropriate] further education.’ (HCP, outcome survey) | |

| ii. Difficulty forming a co-located multidisciplinary team within general practice | ‘The difficulty in creating a team in general practice; I’m not working in the same place as the team, and this creates a barrier for development of a team approach.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Access to affordable rehab options is very limited. Even with TCAs [Team Care Arrangement] it’s difficult to create a treating team in general practice.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| iii. Workforce shortages of allied health and other primary care providers | ‘Education regarding pacing and ongoing psychological support require access to disciplines that are unavailable in the public system. An ongoing multidisciplinary team is very hard to initiate and maintain outside of hospital.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| iv. Long waiting lists for specialist tertiary multidisciplinary services | ‘Medicare [hospital] waiting lists.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Access to specialist multidisciplinary teams.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| v. Lack of resources especially for people with low English literacy and low health literacy | ‘Funding access for services for CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) community.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘[Lack of] access to resources especially for low literacy and low health literacy.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| 3. System-level barriers (macro level) | i. Perceived inadequate reimbursement under Medicare (Australia’s national public health insurance scheme) for GPs to have longer consultations to deliver best practice pain care aligned to the biopsychosocial approach | ‘Chronic pain is complex issue. Needs to be individualised and especially important to allow the patient to be heard. Time based MBS (Medicare Benefits Schedule) criteria do not allow this to occur in private practice especially for the vulnerable and poorer people in our communities. In private practice this means unable to maintain business to care for these people appropriately.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Funding is a problem. Having enough time to apply biopsychosocial methods - current funding structure encourages rapid through put and discourages well-considered tailored therapies that result in less medications and less medication accidents.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | |

| ii. Perceived inadequate reimbursement under Medicare for allied health services and group-based programs | ‘Lack of availability of specialised allied health services and if these are available then financial restrictions for easy access.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Sadly, funding grants favour NGOs (non-government organisations) and consider private GPs ineligible which ended our group education sessions. There seems to be discrimination against GPs in these areas. I am too cynical to seek solutions when the seeking takes precious resources that could be spent on patient care.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) | ||

| iii. Perceived misinformation in the mass media with communication not aligned to the biopsychosocial approach to pain care | ‘TV and media depiction of pain killers.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) ‘Current media comments about low value care may be misunderstood when needing to build treatment alliance with these patients.’ (HCP, satisfaction survey) |

Discussion

Healthcare professionals often lack the knowledge, confidence and skills to provide best-practice pain care underpinned by a biopsychosocial approach (Ng et al. 2021). Our study demonstrated that the ECHO Network model was an acceptable and effective interdisciplinary education model for upskilling primary care providers, including GPs and healthcare providers from diverse professional disciplines, in best practice pain care. Our study also highlighted that the ECHO Network model could help overcome the education barriers imposed by distance, with one-third of healthcare professionals participating in the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network working in regional SA.

Participants in the ECHO Network also reported a better understanding of the importance of patient-centred care such as validating the patient experience and learning about the whole person, reflected in the consumer pain care priorities framework (Listen to me, learn from me), empirically derived from Australian people with lived experience of pain, carers and healthcare professionals (Slater et al. 2022). Although the ECHO Network model provided the opportunity for discussion about how to apply patient-centred communication in consultations with patients living with chronic pain, further educational opportunities are needed to practise these skills (Ng et al. 2023).

Participants in the ECHO Network also reported improved awareness of the importance of multidisciplinary team-based care, with most GPs indicating an intention to increase referrals to allied health practitioners. Multidisciplinary team-based care is a key recommendation of the Australian Government, Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report (2022) (Australian Government 2023), building on the direction outlined in the Australian Government Australia’s Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan 2022–2032 (Australian Government 2022). However, a reported barrier to applying the learnings from the ECHO Network was difficulty forming a co-located multidisciplinary team within general practice. Workforce capacity building in teamwork, collaboration and care co-coordination for co-located and non-co-located multidisciplinary teams is critical and further education could be provided by Australian Primary Health Networks given their remit of supporting the primary care workforce (Australian Government 2018).

Two-thirds of primary care providers who participated in the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network managed patients with compensable workplace injuries. Improving healthcare professionals’ knowledge and confidence in applying the biopsychosocial approach to pain care to support injured workers to stay at work or return to work is critical (Beales et al. 2016), and has shown to reduce disability and the psychosocial consequences of chronic pain and prolonged work absence (Furlan et al. 2022). Although the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network improved the self-perceived knowledge and confidence of primary care providers in best practice pain care, the ECHO Network model also has the potential to be implemented in compensable settings, with insurance case managers and medical assessment panels, to improve claims management and outcomes for injured workers.

A key learning of the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network for healthcare professionals was the importance of promoting social connection and participation in community groups as a management strategy for chronic pain. Social prescribing is ‘a means of enabling GPs, nurses and other primary care professionals to refer people to a range of local, non-clinical services’ (RACGP 2020). Implementing social prescribing initiatives is one of the highlighted actions in the Australian Government Australia’s Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan 2022–2032 (Australian Government 2022) for people at risk of developing poor health outcomes. Most social prescribing models involve a link worker or care navigator such as a general practice or community nurse who assist people to access suitable activities and support (Oster et al. 2023). Greater investment is needed in social prescribing, with Australian Primary Health Networks well-placed to implement these initiatives (Thompson et al. 2022).

Although the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was associated with improved self-perceived knowledge and confidence to manage patients with chronic pain, a significant proportion of healthcare professionals (42% across the ECHO series) identified barriers at the clinical, service and system level to applying the learnings. Similar to findings from other studies (Ng et al. 2021; Ng et al. 2023), lack of time during consultations to deliver biopsychosocially informed care (such as listening to patients, teaching patients about self-management, helping patients to set goals and referring them to appropriate community activities) is a major challenge within the current Australian primary care system. The proposed Australian Government MyMedicare primary care reform (2024–25) aims to offer greater support for general practice in the management of complex chronic disease through blended funding models that support longer consultations for people who need it most (Australian Government 2023). Another potential primary care reform strategy that could take pressure off GPs and improve health outcomes is enabling practice nurses to work to their full scope of practice in chronic disease prevention and management, including best practice pain care (Halcomb and Ashley 2019).

Greater Australian and state government investment in multidisciplinary community-based pain self-management programs co-commissioned by Primary Health Networks (De Morgan et al. 2022) and state governments could also reduce pressure on GPs and tertiary specialist clinics. These programs have been shown to be effective in improving patients’ confidence in undertaking daily activities and work, improving patients’ functional capacity and quality of life, reducing opioid usage and reducing hospitalisations (Joypaul et al. 2019). Access to these programs could be increased by adaptation to a virtual or hybrid format, demonstrating similar outcomes to face-to-face formats, although drop-out rates may be higher (Buhrman et al. 2016).

Limitations

Although the average response rate for the satisfaction surveys over the series was 46% (range 34–60%) and a range of professional disciplines was represented, the response rate for the outcome survey was only 25%. The key findings of this study are sourced largely from the satisfaction surveys. Linking CPD points to completion of evaluation surveys may be considered in future evaluations of Project ECHO networks to increase the response rates of the surveys. Other limitations relate to recall and social desirability bias potential leading to inaccurate self-reports.

In our study, effectiveness was measured in terms of learning (perceived knowledge gain, change in attitudes), competence (self-confidence) and performance (intention to change practice, perceived practice change). It was beyond the scope of the study to measure effectiveness in terms of learning (actual knowledge gain); competence (demonstrated competence); performance (actual practice change); patient health; population health or cost impacts/cost-effectiveness. Systematic reviews of ECHO networks have included a limited number of studies that measure these outcomes using robust methodological designs (McBain et al. 2019; Osei-Twum et al. 2022).

Data collection related to the self-perceived barriers for healthcare professionals to apply the learnings was undertaken through surveys only. Further research including in-depth qualitative interview would be useful to comprehensively explore the barriers at the clinical, service and system level.

Conclusions

The ECHO Network model was found to be an acceptable and effective interdisciplinary education model for upskilling primary care providers in best practice pain care aligned to a patient-centred, biopsychosocial approach to pain management. However, primary care providers perceived barriers to translating this knowledge into practice at the clinical, service and system level. The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was funded for 10 sessions over 20 weeks, with further investment from Primary Health Networks, Local Hospital Networks and key stakeholders required to sustain the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of funding

The SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network was implemented and evaluated as part of the National Pain Management Education Project led by Professor Michael Nicholas at the University of Sydney and funded by the Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care (Grant GO2810; 2020–2024) to build health workforce capacity and capability in pain management and as a response to supporting implementation of the National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management. Leveraged funding was provided by ReturnToWorkSA and Country SA Primary Health Network to the South Australian Postgraduate Medical Education Association (SAPMEA) to implement the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the SA Chronic Pain ECHO Network Advisory Group, Helen Ho from the South Australian Postgraduate Medical Association (SAPMEA), the Hub panel members, GP facilitator, and healthcare professionals who participated in the evaluation. Thank you also to Professor Helen Slater for her guidance during the National Pain Management Education Project (2020–2024).

References

AIHW (2020) Chronic pain in Australia. vol. cat. no. PHE 267. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra). Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/10434b6f-2147-46ab-b654-a90f05592d35/aihw-phe-267.pdf.aspx

ANZCA (2023) National strategy for health practitioner pain management education. Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/national-strategy-for-health-practitioner-pain-management-education.pdf

Australian Government (2022) Australia’s primary health care 10 year plan 2022–2032. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australias-primary-health-care-10-year-plan-2022-2032

Australian Government (2023) Strengthening Medicare Taskforce report. (Australian Government) Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/strengthening-medicare-taskforce-report_0.pdf

Australian Government Department of Health (2019) The national strategic action plan for pain management. (Australian Government Department of Health Canberra, Australia). Available at https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/the-national-strategic-action-plan-for-pain-management

Beales D, Fried K, Nicholas M, Blyth F, Finniss D, Moseley GL (2016) Management of musculoskeletal pain in a compensable environment: implementation of helpful and unhelpful Models of Care in supporting recovery and return to work. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 30(3), 445-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Buhrman M, Gordh T, Andersson G (2016) Internet interventions for chronic pain including headache: a systematic review. Internet Interventions 4, 17-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chouinard JA, Milley P (2018) Uncovering the mysteries of inclusion: Empirical and methodological possibilities in participatory evaluation in an international context. Evaluation and Program Planning 67, 70-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

De Morgan S, Walker P, Blyth FM, Nicholas M, Wilson A (2022) Community-based pain programs commissioned by primary health networks: key findings from an online survey and consultation with program managers. Australian Journal of Primary Health 28(4), 303-314.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Deloitte (2019) The cost of pain in Australia. Deloitte Access Economics. Available at https://www.deloitte.com/au/en/services/economics/analysis/cost-pain-australia.html

Furlan AD, Zhao J, Voth J, Hassan S, Dubin R, Stinson JN, Jaglal S, Fabico R, Smith AJ, Taenzer P, Flannery JF (2019) Evaluation of an innovative tele-education intervention in chronic pain management for primary care clinicians practicing in underserved areas. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 25(8), 484-492.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Furlan AD, Harbin S, Vieira FF, Irvin E, Severin CN, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Tiong M, Adisesh A (2022) Primary care physicians’ learning needs in returning ill or injured workers to work. a scoping review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 32(4), 591-619.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Halcomb E, Ashley C (2019) Are Australian general practice nurses underutilised?: An examination of current roles and task satisfaction. Collegian 26(5), 522-527.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hassan S, Carlin L, Zhao J, Taenzer P, Furlan AD (2021) Promoting an interprofessional approach to chronic pain management in primary care using Project ECHO. Journal of Interprofessional Care 35(3), 464-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hogg MN, Kavanagh A, Farrell MJ, Burke ALJ (2021) Waiting in pain II: an updated review of the provision of persistent pain services in Australia. Pain Medicine 22(6), 1367-1375.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Joypaul S, Kelly FS, King MA (2019) Turning pain into gain: evaluation of a multidisciplinary chronic pain management program in primary care. Pain Medicine 20(5), 925-933.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McBain RK, Sousa JL, Rose AJ, Baxi SM, Faherty LJ, Taplin C, Chappel A, Fischer SH (2019) Impact of Project ECHO models of medical tele-education: a systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(12), 2842-2857.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moore DE, Jr, Green JS, Gallis HA (2009) Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 29(1), 1-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moore DE, Jr, Chappell K, Sherman L, Vinayaga-Pavan M (2018) A conceptual framework for planning and assessing learning in continuing education activities designed for clinicians in one profession and/or clinical teams. Medical Teacher 40(9), 904-913.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moss P, Hartley N, Ziviani J, Newcomb D, Russell T (2020) Executive decision-making: piloting Project ECHO® to integrate care in Queensland. International Journal of Integrated Care 20(4), 23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moss P, Nixon P, Newcomb D (2021) Implementation of the first Project ECHO Superhub in Australia. International Journal of Integrated Care 20(3), 15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moss P, Nixon P, Baggio S, Newcomb D (2023) Turning strategy into action – using the ECHO model to empower the Australian workforce to integrate care. International Journal of Integrated Care 23(2), 16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ng W, Slater H, Starcevich C, Wright A, Mitchell T, Beales D (2021) Barriers and enablers influencing healthcare professionals’ adoption of a biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Pain 162(8), 2154-2185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ng W, Beales D, Gucciardi DF, Slater H (2023) Applying the behavioural change wheel to guide the implementation of a biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal pain care. Frontiers in Pain Research 4, 1169178.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Nicholas MK (2022) The biopsychosocial model of pain 40 years on: time for a reappraisal? Pain 163(Suppl 1), S3-S14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Osei-Twum J-A, Wiles B, Killackey T, Mahood Q, Lalloo C, Stinson JN (2022) Impact of Project ECHO on patient and community health outcomes: a scoping review. Academic Medicine 97(9), 1393-1402.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Oster C, Skelton C, Leibbrandt R, Hines S, Bonevski B (2023) Models of social prescribing to address non-medical needs in adults: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 23(1), 642.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Slater H, Briggs AM, Smith AJ, Bunzli S, Davies SJ, Quintner JL (2014) Implementing evidence-informed policy into practice for health care professionals managing people with low back pain in Australian rural settings: a preliminary prospective single-cohort study. Pain Medicine 15(10), 1657-1668.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Slater H, Jordan JE, O’Sullivan PB, Schütze R, Goucke R, Chua J, Browne A, Horgan B, De Morgan S, Briggs AM (2022) “Listen to me, learn from me”: a priority setting partnership for shaping interdisciplinary pain training to strengthen chronic pain care. Pain 163(11), e1145-e1163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zhou C, Crawford A, Serhal E, Kurdyak P, Sockalingam S (2016) The impact of project ECHO on participant and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Academic Medicine 91(10), 1439-1461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |