Implementation of a data-driven quality improvement program in primary care for patients with coronary heart disease: a mixed methods evaluation of acceptability, satisfaction, barriers and enablers

Nashid Hafiz A * , Karice Hyun A B , Qiang Tu A , Andrew Knight C D , Clara K. Chow F G , Charlotte Hespe E , Tom Briffa H , Robyn Gallagher I , Christopher M. Reid J K , David L. Hare L , Nicholas Zwar M , Mark Woodward N O , Stephen Jan N , Emily R. Atkins N , Tracey-Lea Laba P , Elizabeth Halcomb

E , Tom Briffa H , Robyn Gallagher I , Christopher M. Reid J K , David L. Hare L , Nicholas Zwar M , Mark Woodward N O , Stephen Jan N , Emily R. Atkins N , Tracey-Lea Laba P , Elizabeth Halcomb  Q , Tracey Johnson R , Deborah Manandi

Q , Tracey Johnson R , Deborah Manandi  A , Tim Usherwood N and Julie Redfern A N

A , Tim Usherwood N and Julie Redfern A N

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

Abstract

The study aimed to understand the acceptability, satisfaction, uptake, utility and feasibility of a quality improvement (QI) intervention to improve care for coronary heart disease (CHD) patients in Australian primary care practices and identify barriers and enablers, including the impact of COVID-19.

Within the QUality improvement for Effectiveness of care for people Living with heart disease (QUEL) study, 26 Australian primary care practices, supported by five Primary Health Networks (PHN) participated in a 1-year QI intervention (November 2019 – November 2020). Data were collected from practices and PHNs staff via surveys and semi-structured interviews. Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed with descriptive statistics and thematic analysis, respectively.

Feedback was received from 64 participants, including practice team members and PHN staff. Surveys were completed after each of six workshops and at the end of the study. Interviews were conducted with a subgroup of participants (n = 9). Participants reported positive satisfaction with individual QI features such as learning workshops and monthly feedback reports. Overall, the intervention was well-received, with most participants expressing interest in participating in similar programs in the future. COVID-19 and lack of time were identified as common barriers, whereas team collaboration and effective leadership enabled practices’ participation in the QI program. Additionally, 90% of the practices reported COVID-19 effected their participation due to vaccination rollout, telehealth set-up, and continuous operational review shifting their focus from QI.

Data-driven QI programs in primary care can boost practice staff confidence and foster increased implementation. Barriers and enablers identified can also support other practices in prioritising effective strategies for future implementation.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, COVID-19, data, mixed methods research, primary care, process evaluation, qualitative research, quality improvement.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains a significant global health concern, causing 17,300 deaths in Australia alone in 2021 (Australian Institute of Health Welfare 2023). Primary care plays a pivotal role in both primary and secondary prevention of CHD by identifying and managing risk factors and promoting medication prescription and adherence according to international and national guidelines (Einarsdóttir et al. 2011). Hence, enhancing the quality of CHD care has become increasingly important. One approach is the increasing use of electronic health records (EHRs) in data-driven quality improvement (QI) programs within healthcare settings due to its potential to improve processes and quality of care (Wikström et al. 2019). QI is a continuous, systematic approach that implements small-scale changes to improve performance, achieve better health outcomes and increase knowledge of health professionals (Batalden and Davidoff 2007). QI programs are multifaceted and typically include QI tools such as plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles and data to identify areas for improvement and achieve established targets (Knight et al. 2019). Education is essential in QI programs, equipping healthcare teams with skills and knowledge to implement and sustain improvements. Through structured workshops, webinars and ongoing professional development, it provides practical experience with QI tools, strengthening the reach and sustainability of QI efforts in primary care (Batalden and Davidoff 2007).

Primary care practices have implemented QI programs to improve care for several health conditions including diabetes, CHD and Aboriginal health (Chalasani et al. 2017; Patel et al. 2017; Sibthorpe et al. 2018). However, the effectiveness of these programs varies across healthcare settings and conditions, suggesting challenges in implementation such as resource intensity, difficulty integrating into existing workflows and the need for provider engagement (Patel et al. 2017; Sibthorpe et al. 2018). Understanding these challenges, the ‘QUality improvement in primary care to prevent hospitalisations and improve Effectiveness and efficiency of care for people Living with heart disease (QUEL)’ study was conducted in 52 primary care practices across four Australian states. The 2-year cluster randomised controlled trial (November 2019 – November 2021) included a multifaceted 12-month intervention program designed to enhance the management of CHD in primary care practices through the implementation of data-driven QI strategies (Redfern et al. 2020). By leveraging automated data extraction tools, QUEL aimed to reduce the resource burden on practices and streamline implementation, offering a more sustainable and efficient solution compared to traditional QI approaches.

Although QI programs have demonstrated effectiveness in improving quality of care in health services (Schierhout et al. 2013), limited research explored their acceptabiltiy among health professionals. Only one study, conducted by the US Veterans Health Administration, investigated the acceptability of a QI program for CHD (Damush et al. 2021). This study found the Protocol-guided Rapid Evaluation of Veterans Experiencing New Transient Neurologic Symptoms (PREVENT) QI program to be well-accepted, with satisfaction increasing over the 12-month implementation period. However, the study was conducted within a specific national healthcare system characterised by unique organisational structures and patient populations, limiting the generalisability of its findings to other settings, such as primary care or universal healthcare systems, like those in Australia (Damush et al. 2021). This highlights a gap in understanding the acceptability of QI programs across diverse healthcare contexts.

Along with gaps in understanding acceptability, studies have also identified several barriers and enablers to program implementation. One study highlighted substantial challenges in embedding QI programs into routine practice in Australian primary care settings, including insufficient IT systems, lack of incentives, unclear leadership, and reliance on non-medical staff (Hespe et al. 2022). Similarly, another study examined hospital-based QI initiatives and emphasised the importance of leadership, adequate resources, and structured frameworks (Zhou et al. 2022). Although these studies provide valuable insights into the barriers and enablers of QI programs, significant gaps remain. Hespe et al. (2022) identified challenges in achieving normalisation of QI activities but did not explore data-driven approaches to overcoming these barriers. Zhou et al. (2022) called for further research on tailoring QI strategies to specific healthcare settings, yet primary care remains underexplored compared to hospital settings. Furthermore, neither study examined the impact of external disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on the implementation and sustainability of QI programs (Dale et al. 2023).

This study aims to address these gaps through a mixed methods process evaluation of a data-driven QI program implemented through the QUality improvement in primary care to prevent hospitalisations and improve Effectiveness and efficiency of care for people Living with coronary heart disease (QUEL) study. Specifically, it seeks to: (1) understand acceptability, satisfaction, uptake, utility and feasibility; (2) identify and describe barriers and enablers; and (3) evaluate the effect of COVID−19 on program implementation (Hafiz et al. 2022). By focusing on these aspects within the context of Australian primary care, this research intends to inform scalability, future development, and effective integration of QI programs into routine practice with broader applicability across healthcare systems (Hafiz et al. 2022).

Methods

Study design

A mixed methods process evaluation was conducted to evaluate the 1-year data-driven QI intervention program nested within the QUEL study (Hafiz et al. 2022). Twenty-six Australian primary care practices randomised into the intervention arm of the study participated in the evaluation (Redfern et al. 2020). Intervention practices were within the jurisdictions of 10 Primary Health Networks (PHNs). Five PHNs participated in the intervention program by providing support to practices within their jurisdiction and were also included in the evaluation.

Participants

Participants were included if they were: (1) team members from intervention practices; (2) PHN staff providing external support to the intervention practices in their region; and (3) provided written informed consent.

Data-driven QI intervention

The 12-month multifaceted QI program, delivered between November 2019 and November 2020, aimed to improve CHD management by helping practices achieve risk factor targets outlined in the QUEL study (Supplementary Table S1). The program included six learning workshops during which participants shared and learned effective QI strategies and best practices. The first and sixth learning workshops were half-day events, and the remaining were 1-h webinars. Practices received monthly feedback reports and carried out QI activities, including PDSA cycles, supported by the study team or their PHNs in between the learning workshops. Each practice had an individual SharePoint account for accessing feedback reports, submitting PDSAs, and sharing study resources. An automated data extraction tool integrated into the practice software tracked each practice’s progress towards achieving the risk factor targets (Supplementary Table S1).

Data sources

Data were sought from team members involved in leading the QI activities from the 26 intervention practices via the following data sources:

Learning workshop surveys: Adapted from the Australian Primary Care Collaborative Programs, six surveys, one for each workshop, were sent to team members who attended the workshops. The first learning workshop was delivered face-to-face, whereas the remaining five were delivered online, with paper-based and online surveys used by the participants, respectively (Supplementary file 3).

End-of-program evaluation survey: At the end of the program, team members who led QI changes within their practices were invited to complete a comprehensive survey, adapted from the Evaluation of the Health Care Homes program, to assess the overall intervention program. The survey was sent via online link, email and by post, with a return envelope (Supplementary file 4).

Semi-structured interviews: Individual interviews with a sub-group of practice team members and PHN staff were conducted at the completion of the 12-month program. Participants were invited from both rural and urban practices and from practices representing high, medium and low attendance in the learning workshops. Workshop attendance was classified as low (less than three workshops attended), moderate (three to four workshops attended), and high (five or more workshops attended); based on which practice team members from five practices in each category were invited for the interviews. Staff from the five participating PHNs were also invited to participate in the interviews. The interview guide, developed based on program aims and QI literature, explored key aspects of the program’s implementation, including satisfaction, uptake, barriers, and enablers. Topics included learning workshop participation, support between workshops, use of SharePoint, PDSA cycles, and data for QI in CHD care. The impact of COVID-19 and adaptive strategies used by practices to overcome these impacts were also examined. These interviews provided further depth to the survey findings, offering additional insights into the program’s evaluation and areas for improvement. Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min, were conducted either face-to-face, or via telephone/video conference, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Measures

Practice satisfaction was assessed via individual learning workshop surveys, where team members rated each workshop using a 5- and 10-point Likert scale. Ten-point Likert scales were used in the first and sixth learning workshop surveys, as these were half-day events, allowing for more nuanced feedback given their greater depth of content and longer duration. A 5-point Likert scale was used in the surveys for the second to fifth learning workshops. These sessions were 1 h and focused on specific topics, making a simpler scale more appropriate for capturing feedback. The end-of-program evaluation survey included questions such as ‘I will be able to use what I learned in this workshop’ and ‘The workshops were a good way to learn’, and both were assessed using a 6-point Likert scale. However, the 6-point Likert scale included ‘NA’ as a response; therefore, the question was also analysed as a 5-point Likert scale. Practice-level ratings were derived by averaging the individual responses, as team members reported on their respective practices’ experiences.

Overall satisfaction with workshop content, design and facilitators were assessed via the end-of-program evaluation survey. Participants used a 6-point Likert scale to rate individual domains, with three questions on content, seven on design, and two on facilitators. Practice-level scores were obtained by averaging the responses.

Acceptability of the program was assessed via the end-of-program evaluation survey, where team members indicated their interest in participating in a similar program in future with a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response, which was further explored in the semi-structured interviews.

Barriers and enablers were assessed through the synthesis of all three data sources. Learning workshop surveys prompted participants to provide free-text responses about challenges and successes in achieving targets for improving CHD care. The end-of-program evaluation survey included free-text responses regarding the least and most useful aspects of the program. Semi-structured interviews again further explored these barriers and enablers.

The effect of COVID-19 was measured via the end-of-program evaluation survey, where practice team members indicated if COVID-19 impacted their participation in the QI program with a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response. If multiple team members from one practice responded, the most frequent response was averaged to reflect practice-level responses. However, there were no discrepancies in the answers between the team members from the same practice. Participants also provided examples via free-text responses in the surveys to elaborate on their responses. Semi-structured interviews further explored and identified themes to understand the effect of COVID-19 on the program implementation.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistical analysis was used to analyse quantitative data from the surveys. Responses and measurements were presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Median and interquartile ranges were used for continuous variables, specifically to summarise the number of general practitioners (GPs) in the participating practices, as there data were not normally distributed. For Likert-scale responses, a score of ≥8/10 or ≥4/5 indicated positive satisfaction, acceptability, and utility of the intervention program.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and free-text survey responses. The survey data were analysed in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation), whereas interviews were transcribed verbatim via Zoom transcription services and analysed using NVivo (Lumivero). Transcripts were cross-checked for accuracy against the recording and independently analysed in duplicate by two researchers (NH and DM). Each researcher selected quotes, identified codes and themes (Naeem et al. 2023). Both researchers then compared their codes and themes manually, and any disagreement in coding and defining the themes was resolved through discussion with a third researcher (KH). The thematic analysis followed an inductive approach, allowing themes to be identified during the analysis (Dawadi 2020). If data regarding satisfaction and acceptability were captured from various sources, they were triangulated for cross-validation and reported together.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval has been obtained from the New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (HREC, HREC/18/CIPHS/44). No individual patient data were used for the process evaluation. Written consent was obtained from the practice team members and PHN staff before conducting semi-structured interviews. Each participating practice signed a Health service agreement, and if a practice wished to withdraw from the study, they were free to do so at any time.

Results

Participating practices and PHN staff

Twenty-six primary care practices from the QUEL study participated in the process evaluation, representing both urban (n = 22) and rural (n = 4) areas across four Australian states. Of these practices, 69% (18/26) were from New South Wales, 15% (4/26) from Victoria, 12% (3/26) from South Australia and 4% (1/26) from Queensland. The median (interquartile range) number of GPs in participating practices was 7 (3, 9), ranging between 1 and 18 (Table 1). Eleven practices (42%) attended five or more learning workshops, another 11 (42%) attended three or four learning workshops and four (16%) practices attended two or fewer workshops.

| Primary care practices | ||

| Number of participating primary care practices (n) | 26 | |

| Urban vs rural practices, n (%) | 22 (85%) vs 4 (15%) | |

| No. of GPs, median (IQR) | 7 (3, 9) | |

| Range of GPs (Min–Max) | 1–18 | |

| States, n (%) | ||

| NSW | 18 (69) | |

| Victoria | 4 (15) | |

| South Australia | 3 (12) | |

| Queensland | 1 (4) | |

| Primary Health Networks | ||

| Number of participating PHNs (n) | 5 | |

| Range of PHN staff | 1–4 | |

| States | ||

| NSW | 2 | |

| Victoria | 1 | |

| South Australia | 1 | |

| Queensland | 1 | |

GP, general practitioner; PHN, primary health network; IQR, interquartile range.

Fifty-four individual practice team members, including GPs, practice managers, nurses, administration, and research staff and 10 PHN staff provided feedback via learning workshop surveys, end-of-program evaluation surveys and semi-structured interviews (Tables 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Six team members from five practices with high workshop attendance and two team members from two practices with moderate workshop attendance accepted the invitation and participated in the interviews. However, none of the practices with low attendance participated despite being invited. All 10 PHN staff provided feedback via learning workshop surveys, with one participating in a semi-structured interview.

| Feedback sources | Practice team members | PHN staff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data sources | • Learning workshop surveys, • End-of-program evaluation surveys, • Semi-structured interviews | • Learning workshop surveys, • Semi-structured interviews | |

| Total participants, n | 54 | 10 | |

| Learning workshop survey, n | 53 | 10 | |

| End-of-program evaluation survey, n | 35 | Nil | |

| Both the learning workshop survey and end-of-program evaluation survey, n | 32 | Nil | |

| Semi-structured interview, n | 8 | 1 |

n = No. of practice team members and PHN staff who provided feedback via the data sources.

PHN, Primary Health Network.

Participants’ satisfaction with different features of the QI intervention program

Between one and three team members from each practice completed the surveys.

Across the six learning workshops, participants expressed positive feedback, both in surveys and interviews. Overall, 94% (17/18) of practices in learning workshop one and 76% (13/17) in learning workshop six rated them with high satisfaction (Table 3). The qualitative data further elucidated participants’ perceptions of the workshops.

| Learning workshop No | No. of practices that provided feedback, N | No. of practice team members that provided feedback | ProportionA of practices scoring 8, 9, 10B ; n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning workshop rating | ||||

| Learning workshop 1 | 18 | 26 | 17/18 (94%) | |

| Learning workshop 2 | 16 | 20 | 14/16 (88%) | |

| Learning workshop 3 | 14 | 16 | 10/14 (71%) | |

| Learning workshop 4 | 11 | 14 | 11/11 (100%) | |

| Learning workshop 5 | 10 | 11 | 9/10 (90%) | |

| Learning workshop 6 | 17 | 25 | 13/17 (76%) | |

Workshop number: Participants reported in the interviews that they felt the number of workshops delivered during the 12 months was satisfactory, as one participant explained:

We would not have wanted them every month and every 6 months would not have been enough either. It was keeping us connected with what was happening. I think one or two you would not have been satisfactory. (Female, Nurse)

Mode of delivery: The first and sixth learning workshops were initially planned as face-to-face; however, due to COVID-19 restrictions, only the first learning workshop was delivered face-to-face, and the remaining five were delivered via Zoom (Zoom Communications Inc.). Participants expressed satisfaction with the online workshops in the learning workshop survey:

I think this Zoom meeting was an overall success, and the team did a great job in facilitating it. It is always great to listen and learn from others. (Female, Nurse)

Workshop duration: Learning workshops one and six were half-day events, whereas the remaining four were 1-h webinars. Participants found the 1-h webinars appropriate, with 75% (15/20) of practices agreeing that the duration was suitable (Table 4). One participant expressed satisfaction with the workshop duration in the interview:

I think an hour is max because, sitting on Zoom you don’t want to sit more than that. When we’re all busy, I think it needs to be precise, and to the point. (Female, Nurse)

| Workshop aspect and statements rated by the practices | ProportionA of practices scoring 4 or 5B , n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall content | ||

| I was well informed about the objectives of the workshops | 18/20 (90%) | |

| Workshops lived up to my expectations | 15/20 (75%) | |

| The content was relevant to my job | 15/20 (75%) | |

| Overall design | ||

| The objectives were clear to me | 17/20 (85%) | |

| The activities stimulated my learning | 16/20 (80%) | |

| The activities gave me sufficient practice and feedback | 14/20 (70%) | |

| The difficulty level was appropriate | 12/20 (60%) | |

| The pace of the workshops was appropriate | 14/20 (70%) | |

| The duration of the workshops was appropriate | 15/20 (75%) | |

| The quantity of the information presented at the workshops was appropriate | 15/20 (75%) | |

| Instructor | ||

| The instructors were well prepared | 17/20 (85%) | |

| The instructors were helpful | 14/20 (70%) | |

| Overall satisfaction | ||

| I will be able to use what I learned in this workshop | 17/20 (85%) | |

| The workshops were a good way for me to learn this content | 14/20 (70%) | |

Workshop timing: The webinars were delivered during lunchtime and repeated the next day in the evening to maximise practice engagement. Participants appreciated the flexibility, enabling them to attend these workshops outside regular working hours. One participant emphasised the practicality of this flexible schedule in the interview, stating:

Definitely the way to go, because working in general practice it, so it’s go go go from the time they open the front door till they close at night. So doing things outside of working hours or at lunchtime is often the only way that you’re going to get them there. (Male, Practice Support Officer, PHN)

Workshop design and delivery: Participants expressed overall satisfaction with the workshop design and delivery. Team members from 75% (15/20) of practices found the content relevant, 85% (17/20) felt the objectives were clear and 85% (17/20) reported that the instructors were well-prepared (Table 4). The interactive small-group breakout sessions in the workshops were also well-received, as reported in the learning workshop survey:

I think the breakout groups are a great way of giving everyone a chance to contribute when you have a large group. (Female, Program Coordinator, PHN)

Additionally, team members from different practices shared various effective QI strategies during the workshops to improve patient care. Participants found these sessions helpful in gaining insights from real-time experiences, as reported in the learning workshop survey.

This was a great workshop. The sharing of ideas, barriers and lessons learnt is invaluable in informing effective QI strategies. Loved the opportunities for open discussion. (Female, Program Coordinator, PHN)

However, some participants reported that few strategies shared by others were not relevant to all practices in the end-of-program evaluation survey.

Some individual practice ideas that were shared were not necessarily relevant to our practice. (Female, GP)

Throughout the intervention, practices received monthly feedback reports via individual SharePoint accounts to identify gaps in care and stay on track with their improvement targets. Participants expressed satisfaction with these reports, as emphasised by one of the participants in the interview:

You send those reports, they were really useful because I always looked at them and go okay this one look good but that does not and try to focus on improving those things. (Female, Nurse)

As part of the intervention, practices submitted PDSAs via a template provided in their SharePoint account. Participants expressed mixed feedback on PDSAs in the interviews. One participant appreciated the convenience of online submission:

Submitting PDSAs online is better. Then you don’t have all these bits of paper everywhere. It’s all nice and tidy and you can’t lose it. (Male, Practice Support Officer, PHN)

Participants also valued learning about PDSAs from other practices, which helped them to implement new strategies in their practices.

I really liked looking at people’s PDSAs. I like to see small and accomplishable things in a short time and the methodology of how people went about it. (Female, PM)

However, some were reluctant to work with PDSAs in future QI projects.

In fact, our practice is currently working on a QI program with the PHN, and I said to the practice manager I’m happy to be involved, but I don’t want to be doing PDSAs. (Female, Nurse)

Qualitative data from learning workshop surveys also reflected satisfaction with learning from other PDSAs:

I like hearing other PDSA and ideas that have worked. (Female, PM)

Practices received external support from the study team or their PHNs for implementing PDSAs, ensuring attendance in learning workshops and engaging with other intervention features. Participants expressed satisfaction with this support provided in the interviews:

We really appreciate what he [PHN Practice Support Officer] has done for us. Every time he visits, he would be mainly spending time with the practice staff to do with either data cleansing, quality improvement. (Female, GP)

However, in the interview, another participant identified challenges with communication, highlighting opportunities for improvement:

I think that the person of contact changed over time, so that was probably a bit confusing and maybe there was a bit of lack of communication until another person of contact introduced himself. (Female, PM)

Overall program acceptability, feasibility, and utilisation of the program

Qualitative data from interviews revealed that the intervention was well received by the practice team members:

I really enjoyed it. Just the different parameters we were looking at are all important in keeping people out of hospital for cardiovascular disease. There were just so many learning opportunities and so many ways we can make improvements, so it was quite practical. (Female, PM)

Participants were also keen to participate in similar programs in future:

A program like this gives you a little bit of structure, gives you some guidelines, graphs and data to work with. No matter what topic you want to use, it is really helpful. So I’d be happy to engage in that. (Female, PM)

Qualitative data from the end-of-program evaluation and learning workshop surveys revealed similar feedback respectively:

They are very beneficial and keep me and my practice colleagues motivated to find new areas where we can improve the health of our patients, the care we provide. (Female, GP)

Our team of GP’s appeared receptive and interested. (Female, Nurse manager)

These findings were further reinforced by the quantitative data from the end-of-program evaluation survey demonstrating team members from 69% (18/26) of the practices expressed interest in participating in a similar program in the future. However, it is important to note that not all feedback was positive. Eight practices (31%) indicated they were not interested in participating in a similar program in the future, indicating various challenges. Some participants expressed concerns about their current workload in the learning workshop survey, stating, ‘currently too many issues to manage’ (Male, GP). This highlights the need for programs to consider the existing burdens on practice teams when planning future programs. Among the eight practices, six were from urban and two were from rural areas. Of these, two practices had limited participation, and one withdrew from the program. The remaining five practices had medium-to-low attendance in the workshops, which aligns with the concerns raised about the workload and engagement.

Barriers and enablers to implementation

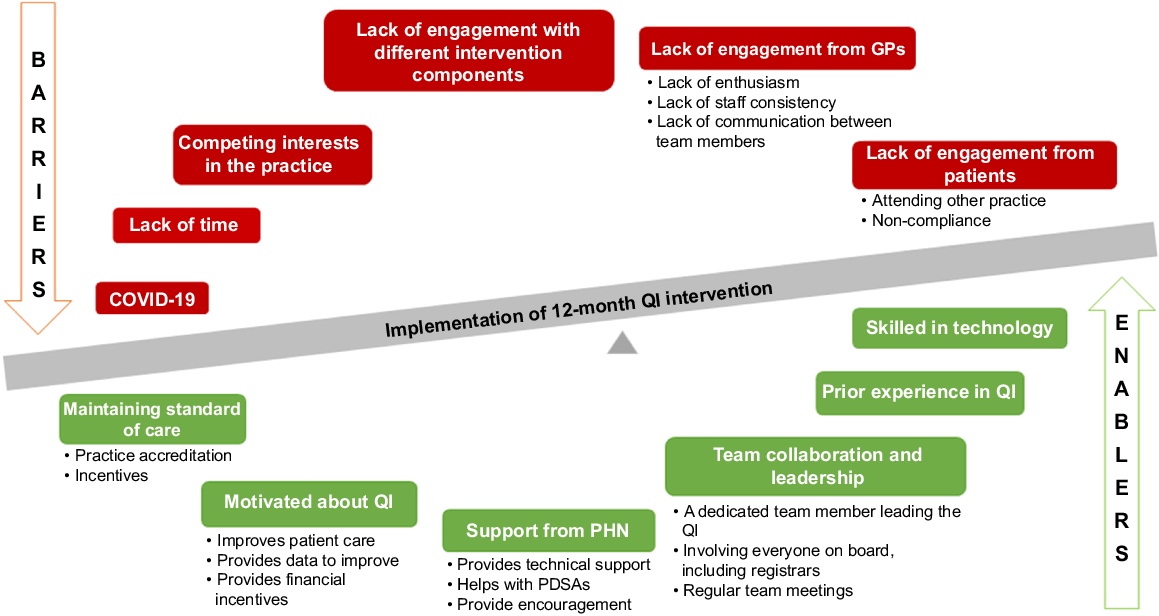

Qualitative data from end-of-program evaluation surveys, learning workshop surveys and interviews identified several themes as barriers and enablers to practices’ engagement with the program (Fig. 1). COVID-19 and time constraints were key barriers, alongside lack of engagement from GPs and patients, and competing interests in practices such as clinical or administrative tasks sidelining QI efforts. Qualitative data further explored practices’ lack of engagement with individual QI features due to workshop fatigue and difficulties attending QUEL online workshops amid other webinars. Some participants perceived PDSAs as tedious, complex to formulate and intimidating, resulting in limited use. There were technical challenges with SharePoint, including forgotten login details and having no prior user experience. Box 1 presents themes and quotes illustrating these barriers.

Barriers and enablers to practices’ participation in the QUEL QI intervention. GP, general practitioner; PDSA, plan-do-study-act; PHN, primary health network; PIP-QI, practice incentive program-quality improvement; QI, quality improvement.

Six themes were identified enabling practices to participate in the intervention (Fig. 1): (1) practice team collaboration and effective leadership; (2) participating in continuous QI programs and accreditation, which involves external assessment to ensure the practices meet required safety and quality standards; (3) previous QI experience; (4) technical skills of the practice team members to use data to generate reports, perform data cleansings; (5) practices motivated about QI as participating in QI helps to improve patient outcomes, improve care and provides financial incentives; and (6) support from PHNs. Themes and quotes associated with enablers are presented in Box 2.

| Box 2.Enablers to program implementation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GP, general practitioner; PDSA, plan-do-study-act cycle; PHN, Primary Health Network; PIP-QI, practice incentive program-quality improvement; PM, practice manager; QI, quality improvement. |

Effect of COVID−19

COVID-19 affected all aspects of primary care services, with 65% (17/26) of the practices reporting its impact on their participation in the QI program. Qualitative data from the end-of-program evaluation survey provided insight into how the pandemic affected the program implementation and overall care provided by the practices (Box 3).

| Box 3.Effect of COVID-19 on QI program participation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BP, blood pressure; GP, general practitioner; PM, practice manager; QI, quality improvement. |

Recommendations for future improvements

Several recommendations were made by the participants for better implementation of future QI programs, including involving the entire practice team to boost engagement, collaborating with good PHNs, and providing training on using data reporting tools and cleansing to maximise efficiency (Box 4). Participants also made several recommendations to increase practice engagement with the different intervention features (Box 4).

| Box 4.Participants’ recommendations for QI program improvement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GP, general practitioner; PDSA, plan-do-study-act cycle; PHN, Primary Health network; PM, practice manager. |

Discussion

The data-driven QI intervention aimed at improving care for people with CHD received mixed satisfaction from practice team members and PHN staff. The findings indicated positive feedback regarding the learning workshops and monthly feedback reports. However, feedback on the use of PDSAs and overall support was mixed, indicating areas for improvement in future implementation. Despite these nuances, the intervention program was well accepted and perceived as useful for identifying gaps, with potential implications for improving patient care. Participants expressed enthusiasm to participate in similar QI programs, reflecting positive uptake and feasibility. Key barriers included the COVID-19 pandemic and time constraints, whereas team collaboration and effective leadership were significant enablers. Furthermore, a majority of the practices’ participation was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic because of vaccination rollout, increased workloads, and ongoing review of practice operations.

QI programs are complex and have multiple features (Batalden and Davidoff 2007), and process evaluation provides detailed insights into the practice team members’ real-time experience with these features (Moore et al. 2015). Our results identified varying acceptance of the different features of the QI program. Although PDSAs are the most commonly used QI tools, participants in this study indicated that they were not a favoured feature of the QI program. Earlier studies also reported PDSAs as time-consuming and difficult to implement in clinical practice (McNicholas et al. 2019; Hespe et al. 2022). Nevertheless, it remains an important part of QI in goal-setting and change management. Another important feature of the QI program was the provision of support or practice facilitation, which previous studies have also emphasised as significant for implementing effective QI (Harvey and Lynch 2017; Hespe et al. 2022). Our study support these findings, revealing that the support received during the program helped practices build relationships and stay motivated.

Several barriers were identified influencing practice team members’ efforts to implement data-driven QI into their routine practices, including time constraints and the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our findings, previous studies have found frequent staff turnover and lack of full-time staff can hinder QI implementation and their participation (Hunter et al. 2017). Additionally, lack of team communication also contributed to non-engagement from the GPs. Furthermore, competing clinical and administrative tasks often take precedence, reducing their QI efforts. Our findings align with previous research, which also identified lack of time, insufficient technical support, and overwhelming workloads as significant challenges in implementing QI (Hespe et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2022). These barriers indicate the need for additional support, such as training in technology and additional personnel to reduce practice workload to improve QI engagement. Although these strategies could not be applied in the current program, they offer valuable insights for future data-driven QI programs.

This study identified several enablers for implementing QI in practice, including team collaboration, leadership, maintaining standards of care, prior QI experience, technological skills, motivation, and PHN support. Previous research highlights practice facilitation, skilled staff, and multidisciplinary collaboration as key enablers (Schierhout et al. 2013; Harvey and Lynch 2017). Another study reinforced the importance of good communication to build effective relationships between PHNs and practices (Damush et al. 2021). Similarly, our study found effective communication motivated practices to undertake QI activities. Furthermore, participation in accreditation programs and regular QI has been associated with improved clinical outcomes and processes of care for patients with various health conditions including CVD and diabetes, encouraging further QI activities (Alkhenizan and Shaw 2011). These findings highlight the need for tailored strategies to enhance communication, support, and collaboration among healthcare teams to effectively implement QI programs.

Recent technological advancements, particularly the use of EHRs, have facilitated automated data collection, patient filtering, reporting, and GP reminders for healthcare providers, significantly increasing their participation in QI. Previous studies have shown that using EHRs and data to monitor patient care improves patient outcomes (Bravata et al. 2019). In this study, EHRs played an important role in filtering and collecting data to identify gaps in care and providing reminders to GPs to address those gaps. Data on CHD risk factors targets (Supplementary Table S1) were collected, enabling GPs to track progress and assess improvements in patient care. Although the effectiveness of EHRs in improving patient care is well-documented, it is important to acknowledge the challenges associated with their use. They include lack of data quality and concerns about patient privacy and confidentiality among many (Bailie et al. 2015; Hodgkins et al. 2020), suggesting the complexity of implementing and maintaining EHRs in healthcare. This study highlights how the use of EHRs in the QUEL QI program facilitates improving CHD management, underscoring their important role in supporting effective QI programs.

This study has several strengths. It is a large national study involving primary care practices of various sizes in both urban and rural areas across diverse geographical regions, providing a wide representative sample of Australian practices. The use of a mixed method approach, combining qualitative and quantitative data, provided a comprehensive understanding of the program’s satisfaction, acceptability, utility, barriers and enablers to implementation. The study also has limitations; the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased the workloads of the GP practices, affecting their capacity to attend learning workshops, perform QI activities and provide feedback, which limited their participation in both the QI program and process evaluation. Moreover, none of the practices with low attendance participated in the interviews, despite being invited. This absence of interviewees from low-attendance practices represents a significant limitation, as it may introduce bias into the interview data, limiting the generalisability of the findings. The non-randomised selection of participants for the interviews may have led to selection bias. Averaging participants’ responses to reflect practice-level understanding may introduce systematic bias and the retrospective nature of the evaluation may lead to recall bias and subject to confounding.

Conclusion

The mixed methods process evaluation revealed positive satisfaction with the data-driven QI program for improving CHD care. Key barriers included time constraints, limited GP engagement, the COVID-19 pandemic and competing priorities. Conversely, a collaborative team, effective leadership, and participation in accreditation programs and continuous QI enabled successful implementation. These findings offer valuable guidance for informing future QI programs. Further research is needed to build on these findings to enhance their acceptability and sustainability in practices, ultimately improving the quality of care for chronic conditions, including CHD.

Data availability

Data (interview transcripts and survey) data will not be available. Although de-identified by name and place, it may contain contextual information that would enable identification of individual participants.

Conflicts of interest

The funding body and industry partners were not involved in the design of the study; and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results. Amgen and Sanofi Australia have provided cash support to the main study. MW is a consultant to Amgen, Freeline and Kyowa Kirin. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Project Grant (Award Grant Number: GNT1140807). Additional in-kind and cash support was received from the following partner organisations: Amgen (cash support), Austin Health, Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association, Brisbane South PHN, Fairfield General Practice Unit, Heart Support Australia, Improvement Foundation, Inala Primary Care, National Heart Foundation of Australia, Nepean Blue Mountains PHN (cash support), The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Sanofi (provided cash support via the Externally Sponsored Collaboration pathway), South Western Sydney PHN, The George Institute for Global Health (cash support) and The University of Melbourne. JR is funded by a NHMRC Investigator Grant (GNT1143538). KH is supported by the NHMRC Investigator Grant (Emerging leadership 1) (APP1196724). MW is supported by the NHMRC grants (1080206 and 1149987). CR is supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship (APP1136372). TL is funded by a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (APP110230). EA is supported by a National Heart Foundation Australia postdoctoral fellowship (101884). CC’s salary is funded by a Career Development Fellowship level 2 co-funded by the NHMRC and National Heart Foundation Future Leader Award (APP1105447), which supports 0.05 FTE for trial meetings.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is based on part of the corresponding author’s PhD thesis: Hafiz NS. (2024). Process evaluation of a data-driven quality improvement program at Australian primary care practices for improved management of coronary heart disease - a mixed-methods study. (PhD Thesis, The University of Sydney). The authors acknowledge the support of all the PHNs and primary care practices who continue to support the QUEL project, as well as PenCS for providing the services and eHealth data platform for the study; and the Improvement Foundation for their continuous support in the delivery of the QI program and other study partners including: Inala Primary Care, Fairfield Hospital General Practice Unit, Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Heart Support Australia Ltd, Austin Health, Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association, National Heart Foundation, Sanofi, and Amgen. The authors would also like to acknowledge the ongoing contribution of Kane Williams in the legal arrangement and Caroline Wu in the research management of the trial.

References

Alkhenizan A, Shaw C (2011) Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Annals of Saudi Medicine 31, 407-416.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Institute of Health Welfare (2023) Heart, stroke and vascular disease: Australian facts. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-disease/hsvd-facts.

Bailie R, Bailie J, Chakraborty A, Swift K (2015) Consistency of denominator data in electronic health records in Australian primary healthcare services: enhancing data quality. Australian Journal of Primary Health 21(4), 450-459.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Batalden PB, Davidoff F (2007) What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Quality and Safety in Health Care 16(1), 2-3.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bravata D, Myers LJ, Homoya B, Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Perkins AJ, Zhang Y, Ferguson J, Myers J, Cheatham AJ, Murphy L, Giacherio B, Kumar M, Cheng E, Levine DA, Sico JJ, Ward MJ, Damush TM (2019) The protocol-guided rapid evaluation of veterans experiencing new transient neurological symptoms (PREVENT) quality improvement program: rationale and methods. BMC Neurology 19, 294.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chalasani S, Peiris DP, Usherwood T, Redfern J, Neal BC, Sullivan DR, Colagiuri S, Zwar NA, Li Q, Patel A (2017) Reducing cardiovascular disease risk in diabetes: a randomised controlled trial of a quality improvement initiative. Medical Journal of Australia 206(10), 436-441.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dale CE, Takhar R, Carragher R, Katsoulis M, Torabi F, Duffield S, Kent S, Mueller T, Kurdi A, Le Anh TN, McTaggart S, Abbasizanjani H, Hollings S, Scourfield A, Lyons RA, Griffiths R, Lyons J, Davies G, Harris D, Handy A, Mizani MA, Tomlinson C, Thygesen JH, Ashworth M, Denaxas S, Banerjee A, Sterne JAC, Brown P, Bullard I, Priedon R, Mamas MA, Slee A, Lorgelly P, Pirmohamed M, Khunti K, Morris AD, Sudlow C, Akbari A, Bennie M, Sattar N, Sofat R, CVD-COVID-UK Consortium (2023) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular disease prevention and management. Nature Medicine 29, 219-225.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Damush TM, Penney LS, Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Baird SA, Cheatham AJ, Austin C, Sexson A, Myers LJ, Bravata DM (2021) Acceptability of a complex team-based quality improvement intervention for transient ischemic attack: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Services Research 21, 453.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dawadi S (2020) Thematic analysis approach: a step by step guide for ELT research practitioners. Journal of NELTA 25(1–2), 62-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Einarsdóttir K, Preen DB, Emery JD, Holman CDAJ (2011) Regular primary care plays a significant role in secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease in a Western Australian cohort. Journal of General Internal Medicine 26, 1092-1097.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hafiz N, Hyun K, Tu Q, Knight A, Hespe C, Chow CK, Briffa T, Gallagher R, Reid CM, Hare DL, Zwar N, Woodward M, Jan S, Atkins ER, Laba T-L, Halcomb E, Johnson T, Usherwood T, Redfern J (2022) Data-driven quality improvement program to prevent hospitalisation and improve care of people living with coronary heart disease: Protocol for a process evaluation. Contemporary Clinical Trials 118, 106794.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harvey G, Lynch E (2017) Enabling continuous quality improvement in practice: the role and contribution of facilitation. Frontiers in Public Health 5, 27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hespe CM, Giskes K, Harris MF, Peiris D (2022) Findings and lessons learnt implementing a cardiovascular disease quality improvement program in Australian primary care: a mixed method evaluation. BMC Health Services Research 22, 108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hodgkins A, Mullan J, Mayne D, Boyages C, Bonney A (2020) Australian general practitioners’ attitudes to the extraction of research data from electronic health records. Australian Journal of General Practice 49(3), 145-150.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hunter SB, Rutter CM, Ober AJ, Booth MS (2017) Building capacity for continuous quality improvement (CQI): A pilot study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 81, 44-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Knight AW, Dhillon M, Smith C, Johnson J (2019) A quality improvement collaborative to build improvement capacity in regional primary care support organisations. BMJ Open Quality 8(3), e000684.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McNicholas C, Lennox L, Woodcock T, Bell D, Reed JE (2019) Evolving quality improvement support strategies to improve Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle fidelity: a retrospective mixed-methods study. BMJ Quality & Safety 28(5), 356-365.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D, Baird J (2015) Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 350, h1258.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S (2023) A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22, 16094069231205789.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Patel B, Peiris D, Usherwood T, Li Q, Harris M, Panaretto K, Zwar N, Patel A (2017) Impact of sustained use of a multifaceted computerized quality improvement intervention for cardiovascular disease management in Australian primary health care. Journal of the American Heart Association 6(10), e007093.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Redfern J, Hafiz N, Hyun K, Knight A, Hespe C, Chow CK, Briffa T, Gallagher R, Reid C, Hare DL, Zwar N, Woodward M, Jan S, Atkins ER, Laba T-L, Halcomb E, Billot L, Johnson T, Usherwood T (2020) QUality improvement in primary care to prevent hospitalisations and improve Effectiveness and efficiency of care for people living with coronary heart disease (QUEL): protocol for a 24-month cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Family Practice 21, 36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schierhout G, Hains J, Si D, Kennedy C, Cox R, Kwedza R, O’Donoghue L, Fittock M, Brands J, Lonergan K, Dowden M, Bailie R (2013) Evaluating the effectiveness of a multifaceted, multilevel continuous quality improvement program in primary health care: developing a realist theory of change. Implementation Science 8, 119.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sibthorpe B, Gardner K, Chan M, Dowden M, Sargent G, McAullay D (2018) Impacts of continuous quality improvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care in Australia. Journal of Health Organization and Management 32(4), 545-571.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wikström K, Toivakka M, Rautiainen P, Tirkkonen H, Repo T, Laatikainen T (2019) Electronic health records as valuable data sources in the health care quality improvement process. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology 6, 2333392819852879.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zhou S, Ma J, Dong X, Li N, Duan Y, Wang Z, Gao L, Han L, Tu S, Liang Z, Liu F, LaBresh KA, Smith SC, Jr, Jin Y, Zheng Z-J (2022) Barriers and enablers in the implementation of a quality improvement program for acute coronary syndromes in hospitals: a qualitative analysis using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science 17, 36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |