Exploring the associative relationship between general practice engagement and hospitalisation in older carers to potentially reduce hospital burden

Anthony Azer A * , Margo Barr A , George Azer B and Ben Harris-Roxas

A * , Margo Barr A , George Azer B and Ben Harris-Roxas  C

C

A

B

C

Abstract

Caregiving is an essential yet often overlooked component of health care. Although carers play a pivotal role in reducing healthcare costs and improving patient outcomes, they are also prone to psychological and physical burdens that can lead to their own hospitalisation. This study aimed to explore the relationship between the frequency of interactions with general practitioners and hospitalisation rates among caregivers aged ≥45 years in New South Wales, Australia.

This cohort study retrospectively identified participants from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study in New South Wales, linked with national datasets. The cohort comprised 26,004 individuals aged ≥45 years who were caregivers. The primary outcome was hospitalisation within a 7-year period, and the intervention was whether the patient was a high or low general practice (GP) user, ascertained by determining if the average number of annual GP visits was above or below 11, respectively. Data analysis included descriptive statistics and Poisson regression models.

The study found a statistically significant association between high GP use and reduced rates of hospitalisation among caregivers. Caregivers with frequent GP interactions had a relative risk of hospitalisation of 0.514 (95% CI: 0.479–0.550) compared with their counterparts who infrequently used GP services. This association remained significant, even after adjusting for various demographic and health-related factors with an adjusted relative risk of 0.619 (95% CI: 0.554–0.690).

The findings underscore the potential of primary care interventions in reducing hospitalisations among caregivers, in turn providing economic and societal benefits. They also highlight the need for future research to understand the specific aspects of GP interactions that contribute to this protective effect.

Keywords: aged, caregiver burden, caregivers, general practice, health burden, hospitalisation, middle aged, preventative medicine.

Introduction

Carers are individuals who provide long-term, unpaid care for individuals who have a chronic or disabling condition (Barbosa et al. 2011; Thomson et al. 2014–2019). In 2018, 2.65 million people in Australia provided informal care to someone with a disability or a chronic illness, translating to approximately one in 10 Australians, or one in five among Australians aged ≥45 years, with the majority being women (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018; Barr et al. 2020). Furthermore, this number has steadily increased over recent decades due to Australia’s aging population and a correlative rise in the prevalence of chronic health conditions (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018; Welberry et al. 2019; Steverson 2022).

In Australia, caregivers play a significant yet undervalued role in reducing the use of the tertiary healthcare system by providing care and support to individuals with chronic health conditions or age-related illnesses (Arno et al. 1999; Bastawrous 2013). Nationally, informal caregiving is estimated to contribute approximately $60 billion to the economy annually by reducing the need for formal healthcare services and institutional care (Productivity Commission 2011). It has also been demonstrated that carers reduce the risk of hospital readmission when engaged in care upon a patient’s discharge (Rodakowski et al. 2017). Therefore, carers represent a substantial societal economic benefit (Cohen et al. 2002; Sherman 2019; The Office of the Ryoal Commission 2019), sustained by the fact that home care with unpaid caregivers is more cost-effective than residential care or hospital care with paid carers (Langa 2009).

Despite the positive societal, economic and medical effects of caregiving, it has several psychological, physical and financial burdens for the caregiver individually. This cumulative burden can ultimately precipitate the need for medical intervention or hospitalisation (Hill et al. 2011; Adelman et al. 2014; Hussain et al. 2016; Pristavec 2019). Such burdens arise from the intense, unpredictable and constant nature of the care required, lack of time to seek support, financial hardship due to caregiving responsibilities and lack of assistance in their caregiver role. The ramifications of these burdens are twofold, both hindering the ability of caregivers to provide quality care (Raina et al. 2004; Etters et al. 2008) and disincentivising others from caregiving for their family members (Bevans and Sternberg 2012). These multifaceted difficulties collectively culminate in caregivers experiencing reduced overall well-being (Cummins et al. 2007; Cummins 2010). Furthermore, caregiving has consistently been associated with higher levels of psychological distress in Australia and similar nations when compared with non-carers (Sisk 2000; Schulz and Sherwood 2008; Bauer and Sousa-Poza 2015; Hussain et al. 2016; Corey et al. 2018; Pristavec 2019; George et al. 2020; Haley et al. 2020). Poorer mental and physical health in carers has been found in a New South Wales (NSW) study by George et al. (2020), as well as several other Australian studies (Edwards et al. 2008; Mohanty and Niyonsenga 2019). The literature also suggests that caregiving could be associated with a deterioration of the caregiver’s physical health (Schulz and Sherwood 2008; Bauer and Sousa-Poza 2015) and the incidence of chronic health conditions (Stacey et al. 2018). Although not all caregivers suffer negative physical health impacts, studies have shown that high levels of caregiving with ongoing paid employment, and increased emotional strain can increase the risk of adverse health effects and mortality, particularly in female caregivers (Schulz and Beach 1999; Kenny et al. 2014). Financially, carers have, on average, lower income levels due to reduced hours of work, and are more likely to exit the labour force on account of their caregiving responsibilities (Bittman et al. 2007; Hill et al. 2011; Hill and Broady 2019). The burdens of the carer role, paired with the high incidence and societal dependence on caregivers (Productivity Commission 2011; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018), highlight the need for institutions to better support caregivers and minimise negative implications of caregiving (Schulz and Eden 2016).

General practitioners (GPs) occupy a uniquely advantageous position to identify caregivers and address their problems. This is because they have pre-existing rapport with patients and, as the gatekeepers to the wider healthcare system, are the most frequently accessed healthcare provider, with a majority of patients visiting their GPs at least annually (Gordon et al. 2022). GPs could also interface with carers who do not self-identify and would otherwise be unaware of the option to receive specialised care, which is the case for a significant proportion of carers (Peters et al. 2020). Furthermore, being highly qualified healthcare professionals, GPs are well situated to monitor the mental and physical health of caregivers on an ongoing basis. Recognising that caregivers, particularly those not coping with their role, may not have the time or the initiative to seek out resources for self-care and support, GPs could potentially represent an avenue whereby carers can receive personalised care suitable to their needs. An online survey of 612 carers found that 72% of them consulted their GPs in care matters (Wangler and Jansky 2021). Nonetheless, despite the pivotal role of GPs in addressing caregiver health, less than one-third of carers were asked about their own needs in GP consultations with the person they care for (Carers NSW Research Team 2018).

Despite the critical role carers play within the healthcare system and the evidenced burden on them, in-depth investigation into the extent and intensity of the caregiver burden has been a historically neglected area of research (Hoffmann and Mitchell 1998). Additionally, within the sphere of caregiver outcomes, even fewer studies investigated carers in the context of GP intervention, with none investigating the impact of GP interaction to prevent adverse outcomes, such as hospitalisations.

This research aimed to investigate if frequent use of GPs is associated with a reduced likelihood of hospitalisation in carers aged ≥45 years.

Methodology

This study used the existing UNSW Primary and Community Health Linkage Resource, based on the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study.

Preparation of the dataset

The study design was a cohort study with participants retrospectively identified and prospectively compared. We used the UNSW Primary and Community Health Linkage Resource, which included the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study in NSW. The 45 and Up Study recruited a demographically representative population of NSW totalling 267,357 participants aged ≥45 years, who completed a baseline survey questionnaire on various sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics. These participants were recruited between 2005 and 2009, and all gave written consent for health data linkage and follow up prior to participation (Banks et al. 2008; CHeReL 2023). Further intricacies of this study have been described elsewhere (Banks et al. 2008; Bleicher et al. 2023).

Medicare claims data were provided by the Services Australia Medicare enrolment database, which encompassed almost the entire cohort, with people aged ≥80 years, and residents of rural and remote areas being oversampled. Linkage of the 45 and Up Study cohort data to these datasets was facilitated by the Sax Institute using a unique identifier and deterministic matching. The 45 and Up Study baseline data were also linked by the Centre for Health Record Linkage to hospital records from the Admitted Patient Data Collection, and death notifications from the NSW Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages. The Centre for Health Record Linkage uses a probabilistic procedure to link records, in which records with an uncertain probability of being true matches are checked by hand. Secure data access was provided through the Sax Institute’s Secure Unified Research Environment.

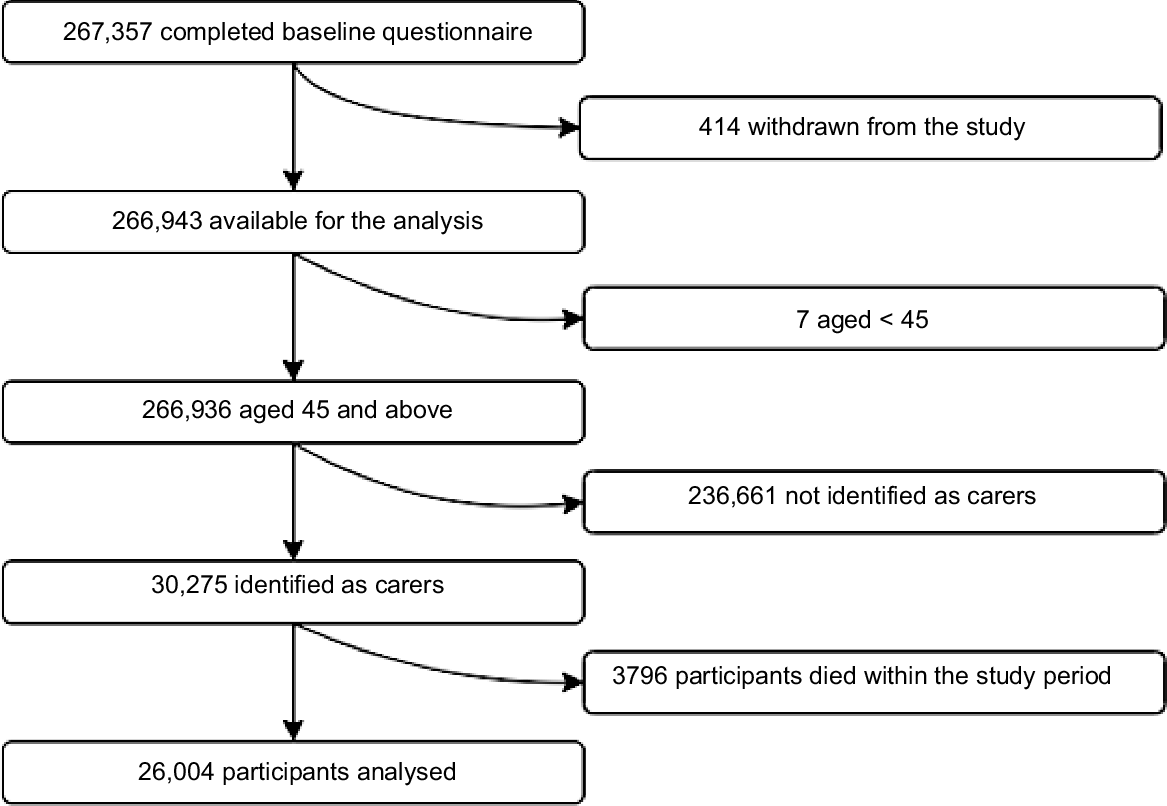

The analytic cohort was limited to carers using a 45 and Up Study’s baseline survey question: ‘Do you regularly care for a sick or disabled family member or friend?’. The inclusion criterion was defined as respondents who affirmed this query. Exclusion criteria included those who died during the exposure or follow-up periods, as ascertained via the Deaths Registry. All-cause mortality was delineated as any fatality that occurred within 10 years after the baseline survey (Fig. 1).

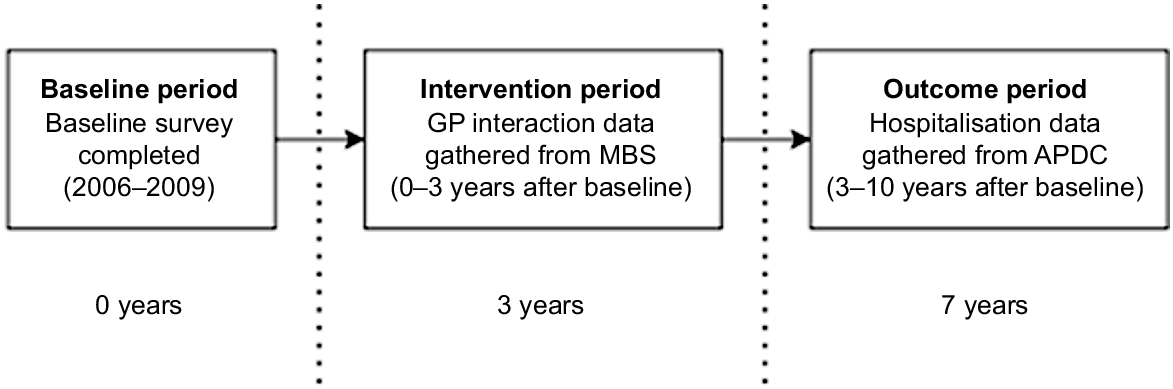

The follow-up time for GP interactions was set at 3 years from the baseline survey, given that the baseline data collection had been completed in December 2009. GP interactions that occurred within 3 years of recruitment were the primary focus of the study.

GP use and hospitalisation admission

GP interactions were ascertained from specific Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item numbers. These item numbers pertained to various GP encounters, including short and long GP encounters, non-referred presentations, health assessments, GP care plans, after-hours GP care and medication management reviews (see Appendix 1). If a participant had an entry bearing any of these specific MBS item numbers, they were considered to have had the respective GP interaction. Accordingly, participants were classified based on their frequency of GP interactions: high GP users were those who had engaged in ≥11 GP interactions per year, a criterion that accounts for a variety of factors, including average Australian GP visits (Harris-Roxas et al. 2023). Carers who engaged in an average of <11 GP visits per year, including those who had no GP visits at all, were classed as low GP users.

For hospitalisation status, Admitted Patient Data Collection hospitalisation records were selected to include entries that had occurred within the follow-up period; between 3 and 10 years after the baseline survey (Fig. 2). Participants with a hospitalisation entry in this period were categorised as ‘hospitalised’, with the time until hospitalisation calculated. Those without a hospitalisation in the period were categorised as ‘non-hospitalised’.

Study timeline

Because each participant completed the baseline survey at different times between 2006 and 2009, the baseline, intervention and outcome periods are all relative to this initial, participant-specific date. Thus, the period in which GP interaction data is gathered commences directly after baseline and lasts 3 years, whereas the period in which hospitalisation data is gathered commences directly after that (Fig. 2).

Data analysis

Analysis was undertaken using RStudio 2023.03.0 + 386 (Posit). Health status, risk factors and demographic characteristics were compared between high and low GP users using Chi-squared tests of Independence, and the P-values were reported.

To explore the relationship between GP use and hospitalisation, we used relative risk (RR) as the primary metric (Clark and Barr 2018). Initial analyses were conducted using a univariate Poisson regression model, which provided crude RRs and their respective 95% confidence intervals. A multivariable Poisson model was employed to adjust for key covariates, notably age and sex, and other significant variables, as identified using Chi-squares P-values <0.05. The adjusted RR, along with its 95% CI, were outputted from this model.

Results

The analytical cohort comprised of 26,004 carers aged ≥45 years (Fig. 1). The percentage of the cohort assessed to have high GP use was 23.9%, which amounts to 6207 participants. Additionally, 243 carers had zero GP visits over the 3-year measurement period, classing them as low GP users.

Demographics and characteristics of carers

The cohort of carers included in this analysis was diverse in terms of age, sex and other demographic characteristics. Table 1 summarises the demographics of the study cohort, as collected from baseline survey.

| Category | Total | Low GP use (%) | High GP use (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | |||||

| 45–59 | 13,385 | 11,257 (84.1) | 2128 (15.9) | <0.01 | |

| 60–74 | 9968 | 7116 (71.4) | 2852 (28.6) | ||

| 75–84 | 2431 | 1306 (53.7) | 1125 (46.3) | ||

| 85+ | 220 | 118 (53.6) | 102 (46.4) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 8431 | 6368 (75.5) | 2063 (24.5) | 0.12 | |

| Female | 17,573 | 13,429 (76.4) | 4144 (23.6) | ||

| Carer status | |||||

| Part-time | 16,741 | 13,496 (80.6) | 3245 (19.4) | <0.01 | |

| Full-time | 9211 | 6265 (68) | 2946 (32) | ||

| Missing | 52 | 36 (69.2) | 16 (30.7) | ||

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight | 2754 | 2039 (74) | 715 (26) | <0.01 | |

| Norm weight | 7583 | 6125 (80.8) | 1458 (19.2) | ||

| Overweight | 9013 | 6932 (76.9) | 2081 (23.1) | ||

| Obese | 6654 | 4701 (70.6) | 1953 (29.4) | ||

| Housing type | |||||

| House | 22,285 | 17,390 (78) | 4895 (22) | <0.01 | |

| Flat or unit | 2943 | 1909 (64.9) | 1034 (35.1) | ||

| Nrs home | 34 | 23 (67.6) | 11 (32.4) | ||

| Other | 502 | 294 (58.6) | 208 (41.4) | ||

| Working status | |||||

| Not working | 13,632 | 9096 (66.7) | 4536 (33.3) | <0.01 | |

| Part time | 5691 | 4860 (85.4) | 831 (14.6) | ||

| Full time | 5895 | 5247 (89) | 648 (11) | ||

| Conditions | |||||

| 0 | 10,858 | 9446 (87) | 1412 (13) | <0.01 | |

| 1 | 9402 | 7120 (75.7) | 2282 (24.3) | ||

| 2 | 4113 | 2503 (60.9) | 1610 (39.1) | ||

| 3+ | 1631 | 728 (44.6) | 903 (55.4) | ||

| Self-reported health | |||||

| Excellent | 3406 | 3082 (90.5) | 324 (9.5) | <0.01 | |

| Very good | 9137 | 7691 (84.2) | 1446 (15.8) | ||

| Good | 9355 | 6746 (72.1) | 2609 (27.9) | ||

| Fair | 3273 | 1857 (56.7) | 1416 (43.3) | ||

| Poor | 467 | 208 (44.5) | 259 (55.5) | ||

| Marital | |||||

| No partner | 5559 | 4077 (73.3) | 1482 (26.7) | <0.01 | |

| Partner | 20,309 | 15,619 (76.9) | 4690 (23.1) | ||

| Annual income (A$) | |||||

| <5000 | 544 | 360 (66.2) | 184 (33.8) | <0.01 | |

| 5000–9999 | 1445 | 849 (58.8) | 596 (41.2) | ||

| 10,000–19,999 | 4340 | 2753 (63.4) | 1587 (36.6) | ||

| 20,000–29,999 | 3009 | 2236 (74.3) | 773 (25.7) | ||

| 30,000–39,999 | 2178 | 1753 (80.5) | 425 (19.5) | ||

| 40,000–49,999 | 1873 | 1554 (83) | 319 (17) | ||

| 50,000–69,999 | 2535 | 2149 (84.8) | 386 (15.2) | ||

| >70,000 | 4699 | 4292 (91.3) | 407 (8.7) | ||

| I would rather not answer the question | 4432 | 3263 (73.6) | 1169 (26.4) | ||

| Missing | 62 | 46 (74.2) | 16 (25.8) | ||

| Highest qualification | |||||

| No school crt. or other qualification | 3373 | 2141 (63.5) | 1232 (36.5) | <0.01 | |

| School or int. crt. | 6168 | 4494 (72.9) | 1674 (27.1) | ||

| Higher school or leaving crt. | 2333 | 1760 (75.4) | 573 (24.6) | ||

| Trade or apprenticeship | 2481 | 1846 (74.4) | 635 (25.6) | ||

| Certificate or diploma | 5786 | 4634 (80.1) | 1152 (19.9) | ||

| University crt. | 5464 | 4650 (85.1) | 814 (14.9) | ||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never smoked | 15,051 | 11,625 (77.2) | 3426 (22.8) | 0.46 | |

| Ex-smoker | 8586 | 6354 (74) | 2232 (26) | ||

| Current smoker | 2365 | 1816 (76.8) | 549 (23.2) | ||

| Standard alcohol per week | |||||

| 0 | 10,224 | 7127 (69.7) | 3097 (30.3) | <0.01 | |

| 1–13 drinks | 11,480 | 9282 (80.9) | 2198 (19.1) | ||

| ≥14 drinks | 3823 | 3104 (81.2) | 719 (18.8) | ||

| Have you ever been told you have depression? | |||||

| No | 18,175 | 14,228 (78.3) | 3947 (21.7) | <0.01 | |

| Yes | 5103 | 3396 (66.5) | 1707 (33.5) | ||

| Self-reported quality of life | |||||

| Excellent | 4842 | 4291 (88.6) | 551 (11.4) | <0.01 | |

| Very good | 8630 | 7105 (82.3) | 1525 (17.7) | ||

| Good | 8118 | 5743 (70.7) | 2375 (29.3) | ||

| Fair | 3031 | 1818 (60) | 1213 (40) | ||

| Poor | 559 | 309 (55.3) | 250 (44.7) | ||

Note: P-values were obtained using the Chi-squared test. BMI, body mass index; crt., certificate; norm, normal; nrs, nursing.

The age distribution of the carers studied showed the majority were aged between 45 and 59 years (51.4%), with the proportion of high GP users increasing with each increasing age group. The proportion of high GP users also increased with the number of chronic conditions the carer had, with 55.4% of those with three or more chronic conditions being high GP users. In terms of sex, the ratio of male to female carers in the cohort was over 1:2, with 17,573 of the total 26,004 participants being female (67.6%). Similarly, the majority of the carers in the cohort were part-time carers (64.3%), with more full-time carers being high GP users (32%) compared with part-time carers (19.4%). Excluding those on an income less than $5000 per year, the proportion of high GP users decreased as income increased, with 41.2% of those earning between $5000 and $9999 being high GP users compared with only 8.7% of those earning above $70,000 per year. The same is largely true for the qualifications of the participants, with more educated subgroups having a lower proportion of high GP use carers (14.9% of university graduates as compared with 36.5% of those who have no school certificate). Self-reported quality of life and self-reported health showed similar trends, with groups who rated their quality of life and health as worse having a greater proportion of high GP users. The same is true for those who had been told they were depressed in the past, with 33.5% of them being high GP users compared with 21.7% of those who had not been told they were depressed.

GP use and hospitalisations among carers

As shown in Table 2, there was a statistically significant association between frequent GP users and hospitalisations among carers with a crude RR of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.48–0.55) and an adjusted RR of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.55–0.69). All of the variables (age, sex, care hours per week, whether the carer cares full time, marital status, body mass index, housing type, work status, highest qualification, income, number of conditions, self-rated quality of life, self-rated health, depression status and alcohol consumption) identified as being significantly different (P < 0.05) using the Chi-squared test (shown in Table 1) were included as covariates in the adjusted model. This indicated that, when adjusted for confounders, carers who are frequent GP users have a 38% lower risk of hospitalisation compared with carers who infrequently utilise their GP.

| No. of carers | Hospitalised (% of total) | Crude RR | Adjusted RR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High GP users | 6207 | 936 (15.1) | 0.51 (95% CI: 0.48–0.55) | 0.62 (95% CI: 0.55–0.69) | |

| Low GP users | 19797 | 5808 (29.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

Note: RR, relative risk; adjusted model included age, sex, care hours per week, whether the carer cares full time, marital status, body mass index, housing type, work status, highest qualification, income, number of conditions, self-rated quality of life, self-rated health, depression status and alcohol consumption as confounders (Barr et al. 2020).

Discussion

The study aimed to investigate an association between GP interaction and hospitalisations in carers, and to investigate if carers with more GP interactions were less likely to be hospitalised. We found that high GP users were less likely to be hospitalised compared with low GP users.

Interpretation of main findings

The main finding of increased GP interaction reducing the risk of hospitalisation aligns with studies undertaken across diverse patient groups and in other countries. For example, among people aged ≥45 years in China, those with primary care outpatient visits were less likely to be hospitalised (Yang et al. 2022), with a similar finding being found among German chronically ill patients (Sawicki et al. 2021). Studying a cohort of 1.5 million Australians, Bazemore et al. (2018) found that increased general practice continuity of care with primary care, a metric that takes into account frequency of visits, was associated with reduced hospitalisations. This association was also found in a 2013 British study that recommended increased continuity of GP care as a solution to reducing the burden on the wider hospital system (Hansen et al. 2013).

Possible explanations for the relationship between increased GP interaction and reduced risk of hospitalisation in the cohort could be explained by the fact that high GP users have consistent communication with their GPs, which facilitates early detection and management of potential health concerns before they escalate to the point where hospitalisation is required (Einarsdóttir et al. 2010). Comparatively, when individuals who do not see their GP as regularly experience escalating medical, emotional or social burdens, delayed intervention may culminate in a need for hospitalisation (Weissman et al. 1991; Sankey et al. 2016). Alternatively, it could be that individuals who are healthier or have greater health literacy are self-selecting to use GPs more (Shahid et al. 2022), hence confounding the association with decreased hospitalisation. Nevertheless, this limitation has been partially mitigated by including overall health and education level demographics in the adjusted model, although it is important to note that health literacy is not always correlative with education level (Shahid et al. 2022).

The characteristics of our study’s cohort also reveal much about the demographics of carers. The increase in the percentage of high GP users from 28.3% in 60–74-year-olds to 46.3% in carers aged >75 years can be explained by a higher percentage of older people visiting their GP generally (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). As shown in Table 1, the proportion of participants who were high GP users increased as self-rated health and quality of life decreased, possibly as a result of those who are more conscious of their needs seeking support more regularly. These findings suggest the potential need for tailored interventions for carers that highlight the potential advantages of engaging with GPs. Additionally, the fact that there were over twice the number of female than male carers aligns with the finding that women are more likely to take on carer responsibilities compared with men (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018; Barr et al. 2020).

Justification of study techniques, strengths and weaknesses

The study employed a retrospective approach to analyse the relationship between GP visits and hospitalisation rates among carers, leveraging a large dataset (26,004 participants) from the 45 and Up Study. This method provided a comprehensive view of long-term outcomes and aligned with established research methodologies. The use of a longitudinal linkage resource was beneficial, as it included both self-identified carers and those not specifically self-labelled as such, enhancing the study’s inclusivity. Additionally, the study cohort was recruited from the community while healthy, allowing it to be more representative of the wider population.

A significant strength of the study was its potential to suggest causation, not just association, between frequent GP visits and reduced hospitalisations, supported by compelling relative risk figures (crude RR 0.51 and adjusted RR 0.62). The research also paid careful attention to temporality, ensuring GP interactions preceded hospitalisations, which is crucial for suggesting a causal relationship. However, the binary categorisation of GP users might have oversimplified the nuanced relationship between GP visits and hospitalisation risks. Future research could benefit from randomised controlled trials to further validate these findings (Farmer et al. 2018; Hariton and Locascio 2018).

Despite its strengths, the study faced limitations. The reliance on pre-existing cohort data meant the research was constrained by the scope of the original data collection, potentially overlooking unknown confounders. The MBS data used lacked detailed information about the GP visits, limiting the depth of analysis regarding the nature of these interactions. Additionally, although the 45 and Up Study data generally represented the demographic well, issues, such as low response rates and oversampling of certain groups (e.g. rural participants (Banks et al. 2008)), could introduce biases. The potential for participants to transition in and out of the carer role also posed a risk for nondifferential misclassification bias (Mitchell et al. 2018), suggesting that the findings should be interpreted as a cautious approximation of the actual impact of GP use on hospitalisation rates among carers.

Implications for research and practice

This study highlighted critical aspects of carer support, particularly the link between carer–GP interactions and hospitalisations. However, it left open questions about what type of these interactions confers the most benefits. It is also unclear whether the frequency, regularity or specific characteristics of GP or carer interactions are crucial in reducing hospitalisations. Future research should explore these nuances and the dynamics of carers transitioning in and out of their roles, as these periods may require tailored GP support.

Despite these uncertainties, the study’s implications for carers, GPs and policymakers are significant. Reducing hospitalisations is crucial from medical, societal and economic perspectives (Langa 2009; Productivity Commission 2011; Bastawrous 2013; Pristavec 2019). The study suggests that promoting GP engagement among carers could be an effective preventive strategy to reduce hospital burden. GPs should recognise their patients who are carers and emphasise regular check-ins to mitigate the risk of hospitalisations. Policymakers, recognising the economic importance of minimising tertiary healthcare admissions (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023), should explore strategies to encourage GP use among carers. This confers a twofold benefit for healthcare burden, whereby carers have a reduced likelihood of being hospitalised, while being able to continue their vital roles, preventing the need for institutional or hospital care for their dependents (Jiwa et al. 2002).

Interventions to enhance GP interaction with carers vary in complexity. Identifying carers within a GP’s practice has shown promise in the UK (Carduff et al. 2016). GPs acknowledge the need for specialised training to better support carers, which could improve care continuity and health follow ups (Wangler and Jansky 2021; Cronin and McGilloway 2023). Enhancing communication tools to facilitate carer access to GPs is another area with potential (Chi and Demiris 2015), although research and clinical trials in this domain are ongoing.

Conclusion

The study revealed that carers aged ≥45 years, with more frequent GP interactions, were 38% less likely to be hospitalised compared with those with fewer GP visits. Although the research design was robust and benefited from a large participant pool, it acknowledged limitations, such as potential unknown confounders and the simplification of GP interactions.

The findings underscore the potential of primary care interventions in Australia to reduce hospitalisations among caregivers, in turn providing economic and societal benefits. They also highlight the need for future research to understand the specific aspects of GP interactions that contribute to this protective effect.

Data availability

The study is accessible to researchers for high-quality research that is in the public interest. Details of the data access policy and procedures are available at the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up website.

Acknowledgements

This research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (http://www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW, and partners the Heart Foundation and the NSW Ministry of Health. We thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study. We also express our sincere gratitude to Dr Alamgir Kabir for his invaluable contribution to the quantitative analysis portion of this research, which significantly enhanced the quality and depth of our work.

Reference

Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS (2014) Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA 311(10), 1052-1060.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM (1999) The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Affairs 18(2), 182-188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings. (ABS Website) Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Older Australians. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians [accessed 20 March 2023]

Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L, Armstrong B, Bauman A, Beard J, Beral V, Byles J, Corbett S, Cumming R, Harris M, Sitas F, Smith W, Taylor L, Wutzke S, Lujic S (2008) Cohort profile: the 45 and up study. International Journal of Epidemiology 37(5), 941-947.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Barbosa A, Figueiredo D, Sousa L, Demain S (2011) Coping with the caregiving role: differences between primary and secondary caregivers of dependent elderly people. Aging & Mental Health 15(4), 490-499.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bastawrous M (2013) Caregiver burden—a critical discussion. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50(3), 431-441.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bauer JM, Sousa-Poza A (2015) Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. Journal of Population Ageing 8, 113-145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Bruno R, Chung Y, Phillips RL, Jr (2018) Higher primary care physician continuity is associated with lower costs and hospitalizations. The Annals of Family Medicine 16(6), 492-497.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bevans M, Sternberg EM (2012) Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA 307(4), 398-403.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bittman M, Hill T, Thomson C (2007) The impact of caring on informal carers’ employment, income and earnings: a longitudinal approach. Australian Journal of Social Issues 42(2), 255-272.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bleicher K, Summerhayes R, Baynes S, Swarbrick M, Navin Cristina T, Luc H, Dawson G, Cowle A, Dolja-Gore X, McNamara M (2023) Cohort profile update: the 45 and up study. International Journal of Epidemiology 52(1), e92-e101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Carduff E, Jarvis A, Highet G, Finucane A, Kendall M, Harrison N, Greenacre J, Murray SA (2016) Piloting a new approach in primary care to identify, assess and support carers of people with terminal illnesses: a feasibility study. BMC Family Practice 17, 18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

CHeReL (2023) Centre for health record linkage (CHeReL). Available at https://www.cherel.org.au/

Chi N-C, Demiris G (2015) A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 21(1), 37-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Clark RG, Barr M (2018) A blended link approach to relative risk regression. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 27(11), 3325-3339.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L (2002) Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 17(2), 184-188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Corey K, McCurry M, Sethares K, Bourbonniere M, Hirschman K, Meghani S (2018) Predictors of psychological distress and sleep quality in former family caregivers of people with dementia. Innovation in Aging 2(1), 851-852.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cronin M, McGilloway S (2023) Supporting family carers in Ireland: the role of the general practitioner. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971-) 192(2), 951-961.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cummins RA (2010) Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: a synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies 11, 1-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Keeping australians out of hospital initiative. Australian Government. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/keeping-australians-out-of-hospital-initiative [accessed 20 March 2023]

Edwards B, Zmijewski N, Gray M, Kingston M (2008) The nature and impact of caring for family members with a disability in Australia. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/rr16_0.pdf

Einarsdóttir K, Preen DB, Emery JD, Kelman C, Holman CDJ (2010) Regular primary care lowers hospitalisation risk and mortality in seniors with chronic respiratory diseases. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25, 766-773.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE (2008) Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20(8), 423-428.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Farmer RE, Kounali D, Walker AS, Savović J, Richards A, May MT, Ford D (2018) Application of causal inference methods in the analyses of randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. Trials 19, 23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

George ES, Kecmanovic M, Meade T, Kolt GS (2020) Psychological distress among carers and the moderating effects of social support. BMC Psychiatry 20, 154.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gordon J, Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Scott A, Harrison C (2022) General practice statistics in Australia: pushing a round peg into a square hole. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(4), 1912.

| Google Scholar |

Haley WE, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Rhodes JD, Huang J, Blinka MD, Howard VJ (2020) Effects of transitions to family caregiving on well-being: a longitudinal population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68(12), 2839-2846.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hansen AH, Halvorsen PA, Aaraas IJ, Førde OH (2013) Continuity of GP care is related to reduced specialist healthcare use: a cross-sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice 63(612), e482-e489.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hariton E, Locascio JJ (2018) Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 125(13), 1716.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris-Roxas B, Kabir A, Kearns R, Webster G, Woodland L, Barr M (2023) Characteristics and Health Service Use of a Longitudinal Cohort of Carers Aged over 45 in Central and Eastern Sydney, Australia. Health & Social Care in the Community 2023, 5032583.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hill P, Thomson C, Cass B (2011) The costs of caring and the living standards of carers. Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Available at https://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/2608/1/The%20costs%20of%20caring%20and%20the%20living%20standards%20of%20carers.pdf [accessed 20 March 2023]

Hoffmann RL, Mitchell AM (1998) Caregiver burden: historical development. Nursing Forum 33(4), 5-11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hussain R, Wark S, Dillon G, Ryan P (2016) Self-reported physical and mental health of Australian carers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6(9), e011417.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jiwa M, Gerrish K, Gibson A, Scott H (2002) Preventing avoidable hospital admission of older people. British Journal of Community Nursing 7(8), 426-431.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kenny P, King MT, Hall J (2014) The physical functioning and mental health of informal carers: evidence of care-giving impacts from an Australian population-based cohort. Health & Social Care in the Community 22, 646-659.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Langa KM (2009) S3-01-05: Informal caregiving for older adults with dementia: economic and health implications. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 5, P119.

| Google Scholar |

Mitchell SE, Laurens V, Weigel GM, Hirschman KB, Scott AM, Nguyen HQ, Howard JM, Laird L, Levine C, Davis TC, Gass B, Shaid E, Li J, Williams MV, Jack BW (2018) Care transitions from patient and caregiver perspectives. The Annals of Family Medicine 16(3), 225-231.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mohanty I, Niyonsenga T (2019) A longitudinal analysis of mental and general health status of informal carers in Australia. BMC Public Health 19, 1436.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peters M, Rand S, Fitzpatrick R (2020) Enhancing primary care support for informal carers: A scoping study with professional stakeholders. Health and Social Care in the Community 28, 642-650.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pristavec T (2019) The burden and benefits of caregiving: a latent class analysis. The Gerontologist 59(6), 1078-1091.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Productivity Commission (2011) Caring for older Australians. Australian Government Productivity Commission, Canberra. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/aged-care/report/aged-care-volume1.pdf

Raina P, O’Donnell M, Schwellnus H, Rosenbaum P, King G, Brehaut J, Russell D, Swinton M, King S, Wong M, Walter SD, Wood E (2004) Caregiving process and caregiver burden: conceptual models to guide research and practice. BMC Pediatrics 4, 1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rodakowski J, Rocco PB, Ortiz M, Folb B, Schulz R, Morton SC, Leathers SC, Hu L, James AE (2017) Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: a metaanalysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65, 1748-1755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sankey CB, McAvay G, Siner JM, Barsky CL, Chaudhry SI (2016) “Deterioration to door time”: an exploratory analysis of delays in escalation of care for hospitalized patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31, 895-900.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sawicki OA, Mueller A, Klaaßen-Mielke R, Glushan A, Gerlach FM, Beyer M, Wensing M, Karimova K (2021) Strong and sustainable primary healthcare is associated with a lower risk of hospitalization in high risk patients. Scientific Reports 11, 4349.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schulz R, Beach SR (1999) Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 282(23), 2215-2219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schulz R, Sherwood PR (2008) Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Journal of Social Work Education 44(sup3), 105-113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shahid R, Shoker M, Chu LM, Frehlick R, Ward H, Pahwa P (2022) Impact of low health literacy on patients’ health outcomes: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Services Research 22, 1148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sherman DW (2019) A review of the complex role of family caregivers as health team members and second-order patients. Healthcare 7(2), 63.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sisk RJ (2000) Caregiver burden and health promotion. International Journal of Nursing Studies 37(1), 37-43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stacey AF, Gill TK, Price K, Taylor AW (2018) Differences in risk factors and chronic conditions between informal (family) carers and non-carers using a population-based cross-sectional survey in South Australia. BMJ Open 8(7), e020173.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Steverson M (2022) Ageing and Health. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health [accessed 20 March 2023]

The Office of the Ryoal Commission (2019) Carers of older australians (background paper 6). Available at https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-12/background-paper-6.pdf

Thomson C, Broady T, Hamilton M, Jops P, Katz I (2014–2019) Review of the NSW Carers Strategy. UNSW Social Policy Research Centre. Available at https://dcj.nsw.gov.au/documents/community-inclusion/carers/nsw-carers-strategy/sprc-report-of-the-review-of-the-nsw-carers-strategy-2014-2019.pdf

Wangler J, Jansky M (2021) Support, needs and expectations of family caregivers regarding general practitioners – results from an online survey. BMC Family Practice 22, 47.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, Epstein AM (1991) Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Annals of Internal Medicine 114(4), 325-331.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Welberry H, Barr ML, Comino EJ, Harris-Roxas BF, Harris E, Harris MF (2019) Increasing use of general practice management and team care arrangements over time in New South Wales, Australia. Australian Journal of Primary Health 25(2), 168-175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Yang S, Zhou M, Liao J, Ding X, Hu N, Kuang L (2022) Association between primary care utilization and emergency room or hospital inpatient services utilization among the middle-aged and elderly in a self-referral system: evidence from the china health and retirement longitudinal study 2011–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(19), 12979.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Appendix 1.MBS items.

MBS item numbers included in the study.

| MBS group | Name of group | Item numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP encounters | |||

| Group A1 | GP encounters to which no other item applies | 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 20, 23, 24, 25, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 43, 44, 47, 48, 50, 51 | |

| Group A2 | Other non-referred presentations to which no other item applies | 52, 53, 54, 57, 58, 59, 60, 65, 81, 83, 84, 86, 87, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 95, 96, 97, 98 (non-GP) | |

| Group A5 | Prolonged presentations to which no other item applies | 160, 161, 162, 163, 164 | |

| Group A7 | Acupuncture and non-specialist practitioner items | 173, 193, 195, 197, 199 | |

| Group A11 | Emergency after-hours attendances | 602, 603, 696, 697, 698 | |

| Group A14 | Health assessments | 700, 701, 702, 703, 704, 705, 706, 707, 708, 709, 7010, 711–14, 715, 716–19 | |

| Group A15 | GP care plans | Preparation of a General Practice Management Plan (GPMP) (721), Team Care arrangement (TCA) (723), Review of a GPMP or TCA (725, 727, 729, 731, 732) | |

| Group A17 | Medication management review | 900, 903 | |

| Group A18 | GP attendance associated with Practice Incentive Program (PIP) | 2497, 2501, 2503, 2504, 2506, 2507, 2509, 2517, 2518, 2521, 2522, 2525, 2526, 2546, 2547, 2552, 2553, 2558, 2559 | |

| Group A19 | Other non-referred attendances associated with PIP payments To which no other item applies | 2598, 2600, 2603, 2606, 2610, 2613, 2616, 2620, 2622, 2624, 2631, 2633, 2635, 2664, 2666, 2668, 2673, 2675, 2677 | |

| Group A20 | GP mental health care | 2700, 2701, 2702, 2710, 2712, 2713, 2715, 2717, 2721, 2723, 2725, 2727, 2729, 2731 | |

| Group A22 | GP after-hours attendances to which no other item applies | 5000, 5003, 5007, 5010, 5020, 5023, 5026, 5028, 5040, 5043, 5046, 5049, 5060, 5063, 5064, 5067 | |

| Group A23 | Other non-referred after-hours attendances to which no other item applies | 5200, 5203, 5207, 5208, 5220, 5222, 5223, 5227, 5228, 5240, 5243, 5247, 5248, 5260, 5263, 5265, 5267 | |