Oral health status and oral health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of clients in an Australian opioid treatment program

Grace Wong A B C D * , Venkatesha Venkatesha E , Mark Enea Montebello F G H , Angela Masoe I , Kyle Cheng A B , Hannah Cook F , Bonny Puszka F and Anna Cheng A

A B C D * , Venkatesha Venkatesha E , Mark Enea Montebello F G H , Angela Masoe I , Kyle Cheng A B , Hannah Cook F , Bonny Puszka F and Anna Cheng A

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

Abstract

Individuals with opioid dependence often experience poor oral health, including dental decay, periodontal disease and mucosal infection, frequently exacerbated by factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, inadequate oral hygiene and low utilisation of oral health services. This study aimed to assess oral health status and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among opioid-dependent individuals and explore their potential associations.

Participants enrolled in an opioid treatment program (OTP) at three Australian urban clinics were assessed using the validated Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) and Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14).

The average age of the 75 participants was 44.7 years, with 45% receiving opioid treatment for over 5 years. Dental decay and inadequate oral hygiene were prevalent. Mean OHAT and OHIP-14 scores were 6.93 and 20.95 respectively, indicating moderate oral health severity and poor OHRQoL. Physical pain and psychological discomfort significantly impacted participants’ quality of life, with the effects being particularly pronounced for those aged 30 and above. An exploratory analysis revealed a strong correlation between OHAT and OHIP-14 severity scores, with a one-point increase in OHAT associated with 1.85 times higher odds of a lower OHRQoL (odds ratio = 1.85, 95% confidence interval: 1.38–2.49, P = <0.001).

These findings underscore the multifaceted impact of oral health on the well-being of OTP clients. Routine dental check-ups, education on oral hygiene practices and timely treatment for oral health problems are crucial recommendations based on this study. Such measures hold the potential to enhance the quality of life for individuals attending OTPs.

Keywords: dental caries, opioid dependence, opioid treatment program, opioid-related disorder, oral health, oral health assessment tool, oral health impact profile, oral health-related quality of life, periodontal disease.

Introduction

The escalating negative impact of opioid addiction has emerged as a significant global issue (Degenhardt et al. 2019). This heightened concern stems primarily from the widespread and far-reaching consequences it brings, including physical dependence and a myriad of adverse health-related outcomes. Notably, individuals grappling with opioid addiction often face a higher prevalence of comorbid mental and physical health problems (Kingston et al. 2017), as well as socio-economic challenges such as unstable housing and homelessness (McLaughlin et al. 2021). In addition, they frequently experience depression (Abdelsalam et al. 2021), thus further complicating their health issues. Research has indicated that these individuals also endure societal stigma and discrimination, compounding the challenges they encounter in seeking care and support (Cama et al. 2016). These multifaceted factors collectively contribute to the profound and intricate impact of opioid addiction on their overall well-being.

In addition to the challenges mentioned above, individuals with opioid addiction also frequently experience a higher incidence of dental caries, periodontal disease and mucosal infection in comparison to the broader general population (Yazdanian et al. 2020). These oral health challenges can be attributable to the direct effect of opioids, including bruxism, xerostomia and suppression of pain sensation as well as lifestyle-related risk factors such as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, suboptimal oral hygiene practices and limited utilisation of oral health services (Baghaie et al. 2017). Moreover, the growing use of pharmaceutical opioid prescriptions for chronic pain (Rosenblum et al. 2008) has resulted in an escalation of dependence on these medications. Such dependence, along with its detrimental oral health outcomes, further contributes to a substantial reduction in overall quality of life.

The recognition of assessing individuals’ quality of life in oral health research has surged, providing a deeper understanding of how diseases and healthcare interventions have impacts beyond physical health. Emphasising its significance, the World Health Organization (WHO) has incorporated this concept into the Global Oral Health Program (WHO 2003), known as Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL). This holistic approach extends beyond mere biological health, encompassing the patient-centred biopsychosocial aspects of daily life that can be affected by oral health outcomes (Baiju et al. 2017). For individuals with opioid dependence, understanding the impact of oral health is crucial, due to their chronic daily challenges. Studies by McIntosh and McKeganey (2000) and Robinson et al. (2005) emphasise that opioid treatment program (OTP) clients have a unique opportunity to address oral health issues during the rehabilitation phase, a period marked by a heightened focus on overall well-being. This phase offers a critical opportunity to integrate oral health into the broader spectrum of care within OTPs. While research shows people who inject drugs (PWID) (Truong et al. 2015) and methamphetamine users (Abdelsalam et al. 2023) experience lower OHRQoL compared to the Australian general population, evidence specific to OTP clients is lacking.

Despite the complexity of this population, integrating oral health into the OTP has been limited, restricting comprehensive access to health care (Poudel et al. 2023). To address this gap, we conducted a cross-sectional study, utilising an interprofessional collaborative approach by partnering Oral Health Services with Drug and Alcohol Services. This study aims to assess the oral health status and OHRQoL among individuals with opioid dependence within the OTP setting. The secondary objective is to explore the potential association between these variables in this population. The findings will inform targeted interventions and policies in developing evidence-based strategies and advocating for routine oral health assessments. The overarching goal is to enhance the overall well-being of individuals undergoing opioid treatment through a holistic healthcare approach.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study adopted an exploratory approach to investigate the oral health status and OHRQoL among clients enrolled in an OTP. Non-random convenience sampling was utilised, involving clients from the OTP operating at three Australian clinics, one private and two public clinics. The public clinics, operated by a local health district of Northern Sydney, offered cost-free opioid treatment services during normal office hours. In contrast, the private clinic had extended operational hours to cater to those with work commitments. Data collection took place during four half-day sessions at each clinic, spanning different days of the week from March to April 2023. Approval for this study was obtained from the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/PID02987).

Participant recruitment

A collaboration was established with Drug and Alcohol Services and Oral Health Services which aimed to broaden the research’s reach and facilitate access to the OTP clients. OTP clients were informed by clinic nurses about the opportunity for a free oral health assessment conducted by the oral health team with the incentive of receiving complimentary oral hygiene products. Upon obtaining verbal consent, clients were directed to the assigned oral health professionals for oral health assessment and questionnaire administration. This collaborative approach not only sought to engage study participants effectively but also provided them with tangible benefits to promote their oral health.

Data collection

Oral health professionals conducted face-to-face interviews to collect socio-demographic information including variables such as age, gender, educational level, employment status, age at the start of substance use, duration of substance use, duration of opioid treatment, alcohol consumption and smoking/vaping history.

The Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) (Chalmers et al. 2005) was preferred over the Decay, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) index (Broadbent and Thomson 2005) for evaluating oral health status due to its broader scope, encompassing comprehensive aspects of oral health beyond just the condition of teeth. Two oral health professionals conducted the assessments after a rigorous standardisation process to ensure consistent and accurate evaluations. The calibration involved training sessions where both assessors independently evaluated sample cases and then compared their assessments, discussing and resolving any discrepancies through consensus. This process helped minimise discrepancies and ensured reliable and comparable assessments.

Oral health assessments were carried out under a portable artificial light, using disposable mouth mirrors and CPI2 (clinical probe) probes. The assessment tool consisted of eight categories, including lips, tongue, gum and tissues, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, oral cleanliness and dental pain. Each category was rated on a scale from 0 to 2 points, where a score of 0 indicated a healthy condition, 1 point showed oral changes and 2 points denoted an unhealthy condition. The total score could range from 0 to 16, with lower scores indicating better oral health. The criteria used for scoring were previously tested for reliability and validity, demonstrating high levels of consistency and accuracy in assessing oral health parameters.

The OHIP-14, developed by Slade and Spencer in 1997, was used to measure the OHRQoL. It assesses individuals’ perceptions of oral health impacts of oral health conditions. Unlike OHAT, it does not directly measure clinical aspects of oral health. The questionnaire comprises 14 questions distributed across seven domains: each domain includes two items, addressing functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability and handicap (John et al. 2014). Participants were asked how often they had experienced a particular impact on their oral health in the past 3 months. Participants rated their responses on a five-point Likert scale: never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3 and always = 4. Total scores range between 0 and 56, with lower scores indicating better OHRQoL. The OHIP-14 provides three distinct measures: ‘prevalence’, ‘extent’ and ‘severity’ (Bhat et al. 2021). Prevalence reflects the percentage of individuals reporting one or more of the 14 items as ‘often’ (3) and ‘always’ (4). The results were dichotomised into two groups, considering only responses coded as 3 or 4 as part of the prevalence calculation. Extent represents the number of items reported at least ‘often’ (3 and 4). Severity is the sum of participant responses, ranging from 0 to 56. Higher extent and severity scores indicate poorer OHRQoL.

The sample size was determined based on the parameter estimation of the mean oral health assessment score and its correlation with OHIP-14 using the Kupper and Hafner (1989) method incorporating an unknown standard deviation. The analysis indicated a requirement of 64 participants for a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) (or 90% power) for the mean oral health score, with a margin of error of 1.0. Assuming an estimated standard deviation of 2 and accounting for a non-participation rate of 10%, a total of 75 participants were included in the study which was sufficient to detect a weak to moderate correlation (r = 0.35) between oral health score measured by OHAT and OHRQoL measured by OHIP-14.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics summarised data, presenting means and standard deviations for normal data and median and ranges for skewed or ordinal data. Proportions were presented with a 95% CI. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and linear regression were used to assess the association between OHAT and OHIP-14. T-tests and ANOVA were used to compare oral health status across demographics.

Exploratory analysis utilised binary logistic regression and Poisson regression to analyse the likelihood and extent of impact. Adjustments for confounding variables were considered in the study. All statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of 0.05, and the analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 75 OTP clients participated in the study, with the sample drawn from a private clinic (n = 20, 26.7%), public clinic 1 (n = 36, 48.0%) and public clinic 2 (n = 19, 25.3%). Table 1 provides an overview of the demographic characteristics of the study participants. Most participants were male (n = 56, 74.7%) and unemployed (n = 56, 74.7%). The mean age of participants was 44.7 years (s.d. = 12.34), with ages ranging from 18 to 72 years.

| Variable | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Private clinic | 20 (26.67) | |

| Public clinic 1 | 36 (48.00) | ||

| Public clinic 2 | 19 (25.33) | ||

| Gender | Female | 19 (25.33) | |

| Male | 56 (74.67) | ||

| Age (years), mean (s.d.) | 44.71 (12.34) | ||

| Education level | Primary school | 3 (4.00) | |

| High school | 42 (56.00) | ||

| TAFE | 21 (28.00) | ||

| University | 9 (12.00) | ||

| Employment status | Work full-time | 6 (8.00) | |

| Work part-time | 5 (6.67) | ||

| Unemployed | 56 (74.67) | ||

| Student | 3 (4.00) | ||

| Retired | 5 (6.67) |

s.d., standard deviation; TAFE, technical and further education.

Substance use and opioid treatment history

Table 2 presents an overview of the substance use and opioid treatment history of the study participants. The analysis revealed that the mean age at the start of substance use was 19.9 years (s.d. = 7.80), with approximately 90% of the participants reporting duration of substance use exceeding 10 years. Approximately 45% of the participants were engaged in opioid treatment for more than 5 years.

| Variable | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the start of substance use (years), mean (s.d.) | 19.97 (7.80) | ||

| Duration of substance use | <12 months | 2 (2.67) | |

| 1–2 years | 1 (1.33) | ||

| 3–5 years | 2 (2.67) | ||

| 5–10 years | 4 (5.33) | ||

| >10 years | 66 (88.00) | ||

| Duration of opioid treatment | Just started | 2 (2.67) | |

| <3 months | 1 (1.33) | ||

| <6 months | 5 (6.67) | ||

| <12 months | 13 (17.33) | ||

| 1–2 years | 10 (13.33) | ||

| 3–5 years | 11 (14.67) | ||

| More than 5 years | 33 (44.00) | ||

| Alcohol use | Never | 49 (65.33) | |

| Daily | 8 (10.67) | ||

| Two to three times a week | 11 (14.67) | ||

| Two to three times a month | 7 (9.33) | ||

| Smoking/vaping history | Yes | 61 (81.33) | |

| Ex-smoker | 6 (8.00) | ||

| Non-smoker | 8 (10.67) |

s.d., standard deviation.

Smoking and alcohol consumption

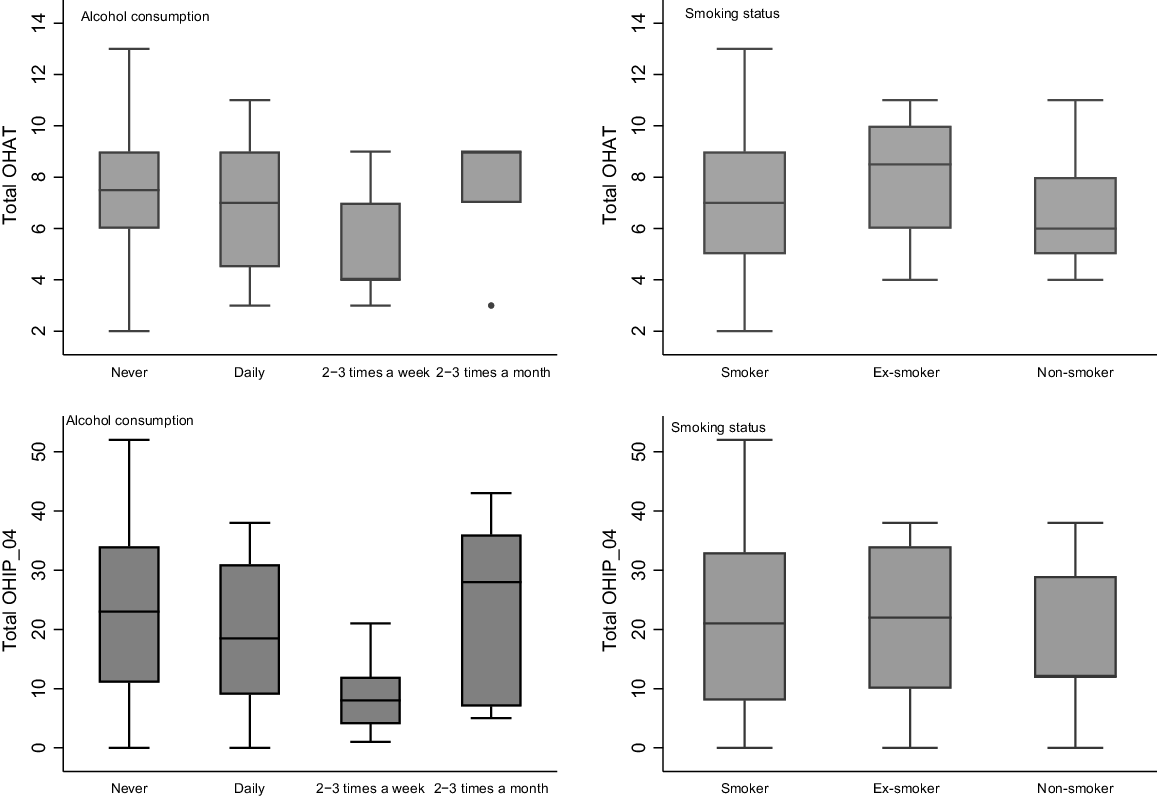

More than 80% of participants reported a history of smoking. In addition, 10.67% of the participants reported daily alcohol consumption. Analysis revealed no significant difference in oral health severity scores across levels of alcohol consumption (P = 0.070) or smoking history (P = 0.530) as shown in Fig. 1.

Box plot of total OHAT and total score across gender, education, employment status, alcohol consumption and smoking history.

In terms of quality of life, no significant differences were observed based on smoking status (P = 0.756). However, a statistically significant difference in OHIP-14 severity scores was noted among different categories of alcohol consumption (P = 0.012), indicating variations in the quality of life based on alcohol intake. Specifically, individuals consuming alcohol two to three times a week exhibited a significantly lower mean OHRQoL score (mean OHIP-14 = 23.18, 95% CI: 14.96–31.40), indicating better OHRQoL compared to those who consumed alcohol daily (mean OHIP-14 = 33.38, 95% CI: 23.73–43.02), two to three times a month (mean OHIP-14 = 39.43, 95% CI: 29.12–49.74), or those who never consume alcohol (mean OHIP-14 = 38.14, 95% CI: 34.25–42.04).

Oral health assessment results (OHAT)

Table 3 summarises the OHAT scores. The total score ranged from 0 to 16, with a mean score of 6.93 (s.d. = 2.46). Notably, lip changes were observed in 97% of participants, while 70% exhibited changes in saliva. Approximately half of all participants had four or more decayed or broken-down teeth and reported dental pain. Furthermore, one-third of the participants exhibited the presence of food debris tartar or plaque in most areas of their mouth, and gum and tissue changes were detected in two-thirds of the participants.

| Category | Healthy (0) | Changes (1) | Unhealthy (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Lips | 2 (2.67) | 72 (96.00) | 1 (1.33) | |

| Tongue | 15 (20.00) | 58 (77.33) | 1 (1.33) | |

| Gums and oral tissues | 24 (32.00) | 38 (50.67) | 12 (16.00) | |

| Saliva | 20 (26.67) | 46 (61.33) | 8 (10.67) | |

| Natural teeth | 12 (16.00) | 14 (18.67) | 48 (64.00) | |

| Denture(s) | 61 (81.33) | 14 (18.67) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Oral cleanliness | 13 (17.33) | 29 (38.67) | 32 (42.67) | |

| Dental pain | 39 (52.00) | 33 (44.00) | 3 (4.00) |

Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14)

Table 4 summarises the prevalence, extent and severity of the OHIP-14. Table 5 presents prevalence rates and their associations with sociodemographic and drug use variables. In the sample, 69.33% (95% CI: 58.17–78.61) scored positive for prevalence. Logistic regression results indicated a statistically significant association with age. Those aged 30–49 years or 50 or older years showed significantly higher odds of experiencing a negative impact compared to those under 30 years (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 20.36, 95% CI: 2.25–184.60 for 30–49 years, adjusted OR 26.60, 95% CI: 2.63–269.41 for 50 or older years). Additionally, the odds of experiencing a negative impact increased by 1.85 times with one-unit increase in the OHAT score, indicating poorer oral health (adjusted OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.38–2.49, P < 0.001). This association suggests that poorer oral health, as assessed by OHAT, correlates with a higher likelihood of adverse impacts on quality of life, as measured by OHIP-14. However, caution should be exercised in interpreting this association, as OHAT and OHIP-14 measure different domains of oral health. While the comparison enhances our understanding of the broader impact of oral health on overall well-being, further validation and contextualisation of these findings may be warranted.

| N = 75 | Prevalence | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||||

| Gender | Female | 12/19 (63.16) | Ref. | ||

| Male | 40/56 (71.43) | 1.46 (0.49–4.37) | 0.501 | ||

| Age (years) | <30 | 1/8 (12.50) | Ref. | ||

| 30–49 | 32/43 (74.42) | 20.36 (2.25–184.60) | 0.007 | ||

| 50 or more | 19/24 (79.17) | 26.60 (2.63–269.41) | 0.005 | ||

| Education | Primary or high school | 31/45 (68.89) | Ref. | ||

| TAFE | 18/21 (85.71) | 2.71 (0.68–10.72) | 0.156 | ||

| University | 3/9 (33.33) | 0.23 (0.05–1.04) | 0.055 | ||

| Employment | Not unemployed | 10/19 (52.63) | Ref. | ||

| Unemployed | 42/56 (75.00) | 2.7 (0.91–7.99) | 0.073 | ||

| Language at home | English | 8/12 (66.67) | Ref. | ||

| Non-English | 44/63 (69.84) | 1.16 (0.60–6.64) | 0.827 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | Never | 37/49 (75.51) | Ref. | ||

| Daily | 6/8 (75.00) | 0.97 (0.17–5.48) | 0.975 | ||

| Two to three times a week | 3/11 (27.27) | 0.12 (0.03–0.53) | 0.010 | ||

| Two to three times a month | 6/7 (85.71) | 1.95 (0.21–17.83) | 0.556 | ||

| Smoking | Current smoker | 41/61 (67.21) | Ref. | ||

| Ex-smoker | 5/6 (83.33) | 2.44 (0.27–22.29) | 0.430 | ||

| Non-smoker | 6/8 (75.00) | 1.46 (0.27–7.91) | 0.658 | ||

| Duration of substance use | <10 years | 4/9 (44.44) | Ref. | ||

| 10 years or more | 48/66 (72.73) | 3.33 (0.80–13.82) | 0.097 | ||

| Duration of opioid treatment | <1 year | 7/8 (87.50) | Ref. | ||

| 1–2 years | 5/13 (38.46) | 0.09 (0.01–0.96) | 0.046 | ||

| 3–5 years | 6/10 (60.00) | 0.21 (0.02–2.48) | 0.217 | ||

| 5–10 years | 5/11 (45.45) | 0.12 (0.01–1.32) | 0.083 | ||

| 10 years or more | 29/33 (87.88) | 1.04 (0.10–10.77) | 0.977 | ||

| Total OHAT score | – | 1.85 (1.38–2.49) | <0.001 |

The perceived extent of the impact, calculated by the total number of items reported at least ‘often’ (codes 3 and 4), showed a mean of 3.78 (s.d. = 3.98). The likelihood ratio test revealed significant overdispersion (P < 0.05) in the Poisson regression model, indicating the need to apply a negative binomial regression model. The summarised findings are presented in Table 6, illustrating the association between socio-demographic and drug use variables and extent scores. Specifically, the 30–49 years and 50 years or more age groups exhibited a significantly higher extent of negative impact than the younger age group (less than 30 years) (incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 33.76, 95% CI: 4.09–78.43 for 30–49 years and IRR = 34.00, 95% CI: 4.04–286.02 for 50 years or more). Additionally, poor oral health, as measured by OHAT, was significantly associated with a higher extent of negative impact on quality of life (IRR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.14–1.42, P < 0.001).

| N = 75 | IRR+ (95% CI) | Mean (s.e.) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Ref. | 4.29 (1.33) | ||

| Male | 0.84 (0.42–1.69) | 3.63 (0.63) | 0.632 | ||

| Age (years) | <30 | Ref. | 0.13 (0.13) | ||

| 30–49 | 33.76 (4.09–78.43) | 4.22 (0.74) | 0.001 | ||

| 50 or more | 34.00 (4.04–286.02) | 4.25 (0.97) | 0.001 | ||

| Education | Primary or high school | Ref. | 4.09 (0.77) | ||

| TAFE | 0.98 (0.50–1.90) | 4.00 (1.12) | 0.947 | ||

| University | 0.44 (0.17–1.15) | 1.78 (0.81) | 0.092 | ||

| Employment | Not unemployed | Ref. | 2.32 (0.70) | ||

| Unemployed | 1.86 (0.94–3.66) | 4.30 (0.73) | |||

| Language at home | English | Ref. | 3.27 (1.29) | ||

| Non-English | 1.18 (0.51–2.72) | 3.87 (0.63) | 0.693 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | Never | Ref. | 4.42 (0.74) | ||

| Daily | 0.88 (0.37–2.08) | 3.88 (1.58) | 0.763 | ||

| Two to three times a week | 0.14 (0.05–0.40) | 0.064 (0.31) | <0.001 | ||

| Two to three times a month | 0.97 (0.39–2.40) | 4.29 (1.85) | 0.945 | ||

| Smoking | Current smoker | Ref. | 3.86 (0.65) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 0.91 (0.31–2.69) | 3.50 (1.85) | 0.858 | ||

| Non-smoker | 0.87 (0.34–2.28) | 3.38 (1.55) | 0.782 | ||

| Duration of substance use | <10 years | Ref. | 2.00 (0.90) | ||

| 10 years or more | 2.02 (0.79–5.15) | 4.03 (0.64) | 0.143 | ||

| Duration of opioid treatment | <1 year | Ref. | 6.43 (2.64) | ||

| 1–2 years | 0.31 (0.11–0.90) | 2.00 (0.71) | 0.032 | ||

| 3–5 years | 0.36 (0.12–1.07) | 2.30 (0.88) | 0.119 | ||

| 5–10 years | 0.21 (0.07–0.65) | 1.36 (0.54) | 0.010 | ||

| 10 years or more | 0.80 (0.33–1.94) | 5.12 (0.98) | 0.616 | ||

| Total OHAT score | 1.27 (1.14–1.42) | – | <0.001 |

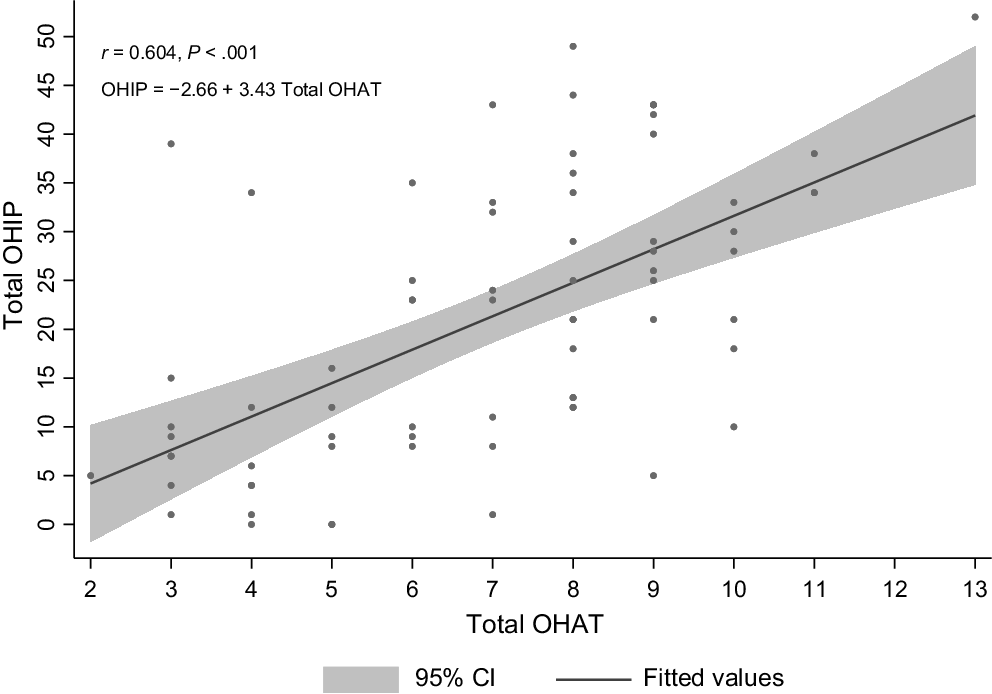

The mean severity score was 20.95 (s.d. = 14.44). A positive and statistically significant correlation was found between oral health (OHAT score) and OHRQoL, as measured by the OHIP-14 scale (n = 75, r = 0.584, P < 0.001), as depicted in Fig. 2. The quantified effect indicated that a one-point increase in the OHAT score was associated with an average increase of 3.43 points (95% CI: 2.43–4.42) in the OHRQoL score (P < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding factors such as age at commencement of substance use, gender and education level, the relationship remained statistically significant with a one-point increase in the OHAT score (representing poorer oral health) associated with a 3.11-point increase (95% CI: 1.91–4.29) in the OHRQoL score (P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study sought to assess the oral health status and oral health-related quality of life among clients attending an OTP, highlighting an often-neglected aspect of their well-being. Findings reveal several key insights into the intersection of opioid dependence, oral health and overall quality of life.

The early onset of opioid use, averaging 19.9 years, aligns with the initiation of substance use typically occurring between 18 and 25 years of age, as reported in the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (2018). Initiating substance use at a young age has significant lifelong health implications.

Oral health assessment insights

The assessment of oral health status using the OHAT revealed several concerning findings. The mean OHAT score of 6.93, out of a possible score of 16, reflects observed changes and highlights areas of weakness that necessitate careful monitoring for potential oral health issues. A higher OHAT score reflects a greater number of oral health issues or more severe problems. Approximately 70% of the participants displayed signs of reduced saliva production which can lead to increased plaque accumulation and acidification of the oral environment, contributing to the development of dental caries (González-Aragón Pineda et al. 2020). Furthermore, the presence of decayed or broken-down teeth and reported dental pain in approximately half of the participants highlights significant oral health challenges faced by this population group. It is noteworthy that in terms of medications, methadone hydrochloride comes in different formulations, including sugar-free Biodone Forte and sugar-based Methadone Syrup. Buprenorphine is offered in tablet and film forms for sublingual administration, with the film version using glucose syrup and citric acid to mask the bitterness of the active agent. There are also long-acting subcutaneous injectable buprenorphine options administered by either weekly or monthly injections. These medications aim to reduce illicit opioid use and enhance overall health. While it is crucial to be aware of the sugar content in these medications (excluding injectable buprenorphine), it is also important to note that oral health issues are influenced by various factors, including oral hygiene practice and regular checks, not solely the medication itself.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing these widely reported oral health problems affected by opioid use (Cossa et al. 2020). Effectively addressing these issues necessitates the implementation of targeted interventions focused on alleviating dental pain, promoting preventive measures, and providing restorative treatment.

Prevalence, extent and severity of oral health impact (OHIP-14)

This investigation revealed a notable prevalence of oral health impact, with 69.33% of individuals reporting items as ‘often’ (3) and ‘always’ (4), highlighting issues related to physical pain and psychological discomfort. Notably, our study found a higher prevalence of oral health impact compared to previous studies on PWID (48%) (Truong et al. 2015) and methamphetamine users (35%) (Abdelsalam et al. 2023) in Australia. The mean extent of the impact, representing the number of items reported at less ‘often’ (3) and ‘always’ (4) was 3.78, significantly higher than in previous studies (PWID study: 2.5, methamphetamine cohort study: 1.58) (Truong et al. 2015; Abdelsalam et al. 2023). This underscores the urgent need for comprehensive oral health interventions to address the broad-reaching effects of poor oral health. Additionally, the mean severity, representing the total sum of participant responses, was 20.95, substantially higher than previous studies (PWID study: 13.5, methamphetamine cohort study: 9.63), indicating significant disparities. These differences may stem from various factors, including differences in study population (sample size and demographics), variations in oral health behaviours, drug use patterns, substance compositions, access to oral health care and measurement methods. Future research is needed to comprehensively understand the specific factors contributing to these disparities and to assess the nuanced impact of opioid treatment on oral health outcomes.

Association with age

The analysis demonstrated a statistically significant association between age and prevalence and the extent of negative impact among OTP clients. Specifically, clients aged 30–49 years and those aged 50 years or older had significantly higher odds of experiencing a negative impact on their quality of life due to oral health issues. This suggests that older clients may be more susceptible to the consequences of poor oral health. A previous study (Roe et al. 2010) has similarly found that the impact of drug use on health status and quality of life escalates with age, highlighting the importance of providing supportive services for treatment and care within this population group.

Influence of smoking and alcohol consumption

In examining the OTP clients, the study explored the influence of alcohol consumption and smoking history on the participants. Over 80% disclosed a history of smoking while approximately 50% reported regular alcohol consumption, consistent with previous findings (Sordo et al. 2017) showing higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption among individuals receiving opioid treatment compared to the general population.

Although no significant association was found between smoking history and oral health status or quality of life, intriguingly, participants who consumed alcohol two to three times a week exhibited notably higher quality of life scores. This suggests that the frequency of alcohol consumption may influence the oral health-related quality of life, possibly due to factors such as social engagement and support (Hajek et al. 2017). However, further research is needed to fully understand this relationship.

Correlation between OHAT and OHIP and its implications for policy

An exploratory analysis revealed a robust positive correlation between participants’ OHAT and OHIP-14 scores. Specifically, a one-unit increase in OHAT score corresponded to 1.85 times higher odds of experiencing a negative impact on quality of life (OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.38–2.49, P < 0.001). This correlation suggests that OHIP-14, which measures self-reported oral health-related quality of life, could potentially serve as a useful proxy for the OHAT, indicating that OHIP-14 alone might be sufficient for identifying oral health needs within an OTP setting.

Using OHIP-14 as a screening tool could be particularly advantageous in settings where clinical oral health assessments are not feasible. It enables OTP clinicians to identify clients with significant oral health issues, facilitating timely referrals and interventions without requiring specialised dental training. This underscores the potential of OHIP-14 for routine screening within OTP settings, ensuring early detection and management of oral health concerns. This approach could inform the development of targeted interventions and policies that prioritise oral health care as a component of holistic treatment strategies within OTPs. Integrating OHIP-14 into standard OTP procedures ensures that oral health is recognised as a critical aspect of overall well-being. Ultimately, this could lead to improved care and health outcomes for OTP clients.

Limitations

This study has notable limitations. Firstly, recruiting participants exclusively from three OTP clinics may limit the generalisability of the findings. Secondly, relying on self-reported quality of life measures, while common, introduces potential subjective bias, as individuals’ perceptions can be influenced by personal feelings, attitudes and experiences. This may result in data that does not accurately reflect objective reality. Additionally, the relatively small sample size limits result precision. Despite these considerations, the study contributes valuable insights into oral health and OHRQoL among individuals in an OTP, offering a foundation for future research in this critical area.

Conclusion

This study highlights the urgent need to integrate oral health into OTPs to address poor oral health and quality of life among OTP clients. Future initiatives should prioritise the development of tailored oral health programs for this vulnerable population. By incorporating comprehensive oral health care, we can significantly enhance their overall well-being and perceived quality of life. Ultimately, this research fills a critical gap in knowledge and provides a vital foundation for informing and driving targeted policy interventions that can lead to more effective and holistic care for OTP clients.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This project was awarded by the Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW Health Special Project Funding FY22/23. The funding source was not involved in preparation of the data or manuscript, only for supporting purchase of oral hygiene products for the participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their heartfelt appreciation to Velda Sturt and Dr Megan Ghaffari from the Oral Health Executive Unit for their invaluable support and express sincere gratitude to Andrea Taylor, Debra Graham, Junhan Liu, Lynda Howlett and the staff at the Opioid Treatment Program Clinics for their cooperation and support, which played a crucial role in the successful execution of this research. Special recognition is extended to Jamal Pakdel, Liuxuan Zhong, Abellyn Criado and Tuyet Llorens from Oral Health Services for their assistance in conducting the study. Their support and collaboration greatly contributed to the successful completion of this study.

References

Abdelsalam S, Van Den Boom W, Higgs P, Dietze P, Erbas B (2021) The association between depression and oral health related quality of life in people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 229, 109121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Abdelsalam S, Livingston M, Quinn B, Agius PA, Ward B, Jamieson L, Dietze P (2023) Correlates of poor oral health related quality of life in a cohort of people who use methamphetamine in Australia. BMC Oral Health 23(1), 479.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Baghaie H, Kisely S, Forbes M, Sawyer E, Siskind DJ (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction 112(5), 765-779.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Baiju RM, Peter E, Varghese NO, Sivaram R (2017) Oral health and quality of life: current concepts. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 11(6), Ze21-Ze26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bhat M, Bhat S, Brondani M, Mejia GC, Pradhan A, Roberts-Thomson K, Do LG (2021) Prevalence, extent, and severity of oral health impacts among adults in rural Karnataka, India. JDR Clinical & Translational Research 6(2), 242-250.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Broadbent JM, Thomson WM (2005) For debate: problems with the DMF index pertinent to dental caries data analysis. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 33(6), 400-409.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cama E, Brener L, Wilson H, von Hippel C (2016) Internalized stigma among people who inject drugs. Substance Use & Misuse 51(12), 1664-1668.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chalmers JM, King PL, Spencer AJ, Wright FAC, Carter KD (2005) The oral health assessment tool — validity and reliability. Australian Dental Journal 50(3), 191-199.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cossa F, Piastra A, Sarrion-Pérez MG, Bagán L (2020) Oral manifestations in drug users: a review. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry 12(2), e193-e200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, Bruneau J, Altice FL, Henderson G, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Larney S (2019) Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. The Lancet 394(10208), 1560-1579.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

González-Aragón Pineda AE, García Pérez A, García-Godoy F (2020) Salivary parameters and oral health status amongst adolescents in Mexico. BMC Oral Health 20(1), 190.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Mallon T, Ernst A, Mamone S, Wiese B, Weyerer S, Werle J, Pentzek M, Fuchs A, Stein J, Luck T, Bickel H, Weeg D, Wagner M, Heser K, Maier W, Scherer M, Riedel-Heller SG, König HH (2017) The impact of social engagement on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in old age – evidence from a multicenter prospective cohort study in Germany. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 15(1), 140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

John MT, Reißmann DR, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, Čelebić A, Szabo G, Rener-Sitar K (2014) Factor analyses of the Oral Health Impact Profile – overview and studied population. Journal of Prosthodontic Research 58(1), 26-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kingston REF, Marel C, Mills KL (2017) A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review 36(4), 527-539.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kupper LL, Hafner KB (1989) How appropriate are popular sample size formulas? The American Statistician 43(2), 101-105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McIntosh J, McKeganey N (2000) Addicts’ narratives of recovery from drug use: constructing a non-addict identity. Social Science & Medicine 50(10), 1501-1510.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McLaughlin MF, Li R, Carrero ND, Bain PA, Chatterjee A (2021) Opioid use disorder treatment for people experiencing homelessness: a scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 224, 108717.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Poudel P, Kong A, Hocking S, Whitton G, Srinivas R, Borgnakke WS, George A (2023) Oral health-care needs among clients receiving alcohol and other drugs treatment – a scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Review 42(2), 346-366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Robinson PG, Acquah S, Gibson B (2005) Drug users: oral health-related attitudes and behaviours. British Dental Journal 198(4), 219-224 discussion 214.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Roe B, Beynon C, Pickering L, Duffy P (2010) Experiences of drug use and ageing: health, quality of life, relationship and service implications. Journal of Advanced Nursing 66(9), 1968-1979.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rosenblum A, Marsch LA, Joseph H, Portenoy RK (2008) Opioids and the treatment of chronic pain: controversies, current status, and future directions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 16(5), 405-416.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, Pastor-Barriuso R (2017) Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. The BMJ 357, j1550.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Truong A, Higgs P, Cogger S, Jamieson L, Burns L, Dietze P (2015) Oral health-related quality of life among an Australian sample of people who inject drugs. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 75(3), 218-224.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Yazdanian M, Armoon B, Noroozi A, Mohammadi R, Bayat A-H, Ahounbar E, Higgs P, Nasab HS, Bayani A, Hemmat M (2020) Dental caries and periodontal disease among people who use drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 20(1), 44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |