Using quick response codes to access digital health resources in the general practice waiting room

Elizabeth P. Hu A B * , Cassie E. McDonald C D , Yida Zhou C , Philip Jakanovski E and Phyllis Lau

C D , Yida Zhou C , Philip Jakanovski E and Phyllis Lau  A F

A F

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

Quick response (QR) codes are an established method of communication in today’s society. However, the role of QR codes for linking to health information in general practice waiting areas has not yet been explored.

This mixed-methods study used both quantitative data measuring QR scans and qualitative data from follow-up semi-structured interviews with visitors to two general practice waiting areas to determine access to an online health information site and their experience of using the QR code. The technology acceptance model was used to guide the interview questions. Quantitative data were analysed descriptively, and qualitative data were analysed thematically using an inductive approach.

A total of 263 QR scans were recorded across the two sites between October 2022 and October 2023. Twelve participants were interviewed. Eleven themes were identified; six were categorised as facilitators and five were barriers to QR code engagement. Motivation for engagement included boredom and curiosity. Facilitators for engaging with the QR code included familiarity secondary to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, benefits of accessing potentially sensitive information with anonymity, convenience of revisiting later and reduced paper waste. Barriers included size and location of the QR code as a limiting factor to engagement, waiting room wait time, privacy and security concerns, and the potential to exclude those without access to technology or those with low technological literacy.

Using QR codes in the general practice waiting area is a convenient method of presenting health information to visitors and patients. Our findings indicate that this may be an appropriate method to share health information in waiting areas. Facilitators and barriers identified in this study may assist with optimising engagement with health information via QR codes while waiting for appointments.

Keywords: general practice, health literacy, health promotion, health services, information disseminatione, primary care, quick response codes, waiting rooms.

Introduction

Health education and promotion in the waiting room of a health service is a common strategy to contribute to healthy literacy and wellbeing in the community (Berkhout et al. 2018). Waiting areas of health services can be effectively used for enhancing patient education and knowledge by sharing targeted health information via audio-visual displays, such as brochures, posters, television and smartphones (Berkhout et al. 2018). Digital resources (e.g. applications and web-based information) are increasingly being used to provide health information in waiting areas (Berkhout et al. 2018).

Despite the potential of education and health promotion in waiting areas to contribute effectively to patient knowledge, behaviours and outcomes, the optimal modes of displaying and providing access to such resources are unclear. A study set in primary care waiting areas in Australia that investigated video health promotion found that although it was the most engaging medium with almost half of respondents remembering watching the television health program, very few participants reported receiving a take home message (Penry Williams et al. 2019). Similarly, a study in primary care waiting areas in the Netherlands found that patients engaged minimally with pamphlets and brochures in the setting of health service waiting areas, with only 2.9% of the brochures taken in the observational period (Jansen et al. 2021). A recent scoping review of the literature found that mixed interventions or digital interventions in health service waiting areas demonstrated potential for improving health literacy and patient outcomes; however, the benefits are short-lived (3–6 months of behavioural change before benefits declined; McDonald et al. 2023).

Quick response (QR) codes are an easy-to-use and efficient method of accessing digital or web-based sites and information. QR codes are a type of two-dimensional barcode that can be interpreted by smartphone cameras as a scanner (Rodrigue 2021). Each QR code consists of squares and dots that represent information, and translates into readable data when scanned (Rodrigue 2021). Invented in 1994, QR codes did not become popularised until smartphones proliferated (Rodrigue 2021). Since then, QR code use has increased exponentially (Rodrigue 2021). QR codes are already in use for training and education of healthcare personnel, as well as the provision of information during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (Karia et al. 2019; Sharara and Radia 2022).

Although QR codes are used in some health contexts, there remains a gap in the literature as to consumers’ perceptions of QR codes as a method of receiving and engaging with educational content within healthcare settings, including in general practice waiting areas. Potentially, QR codes may be a convenient and low-cost method of enabling access to web-based health information in waiting areas. However, previous studies have shown that available health information and resources are not always used by waiting patients (Jansen et al. 2021). Therefore, it cannot be assumed that by making web-based health information available via QR codes, that this will be engaged with by waiting patients.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the number of QR code scans in health service waiting rooms to access web-based health information, as well as the experiences of health service visitors with using QR codes for that purpose.

Research questions

What is the engagement of QR codes by patients and visitors to access digital health resources in general practice waiting rooms?

What are patients and visitors’ experiences and views on using QR codes to access digital health resources in general practice waiting rooms?

Methods

Study design

This mixed-methods study involved both quantitative data from QR code analytics and qualitative data from follow-up semi-structured interviews with visitors to a general practice waiting room. Data collection was conducted in two concurrent parts, between October 2022 and October 2023. Part 1 involved quantitative measurement of the number of QR code scans; and in Part 2, semi-structured interviews underpinned by a positivist paradigm were conducted with participants who chose to sign up after engaging with the QR code. We used COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative (COREQ) research guidelines to guide our reporting (Supplementary File S1).

Setting

Data collection occurred in two general practices located in Melbourne, Victoria.

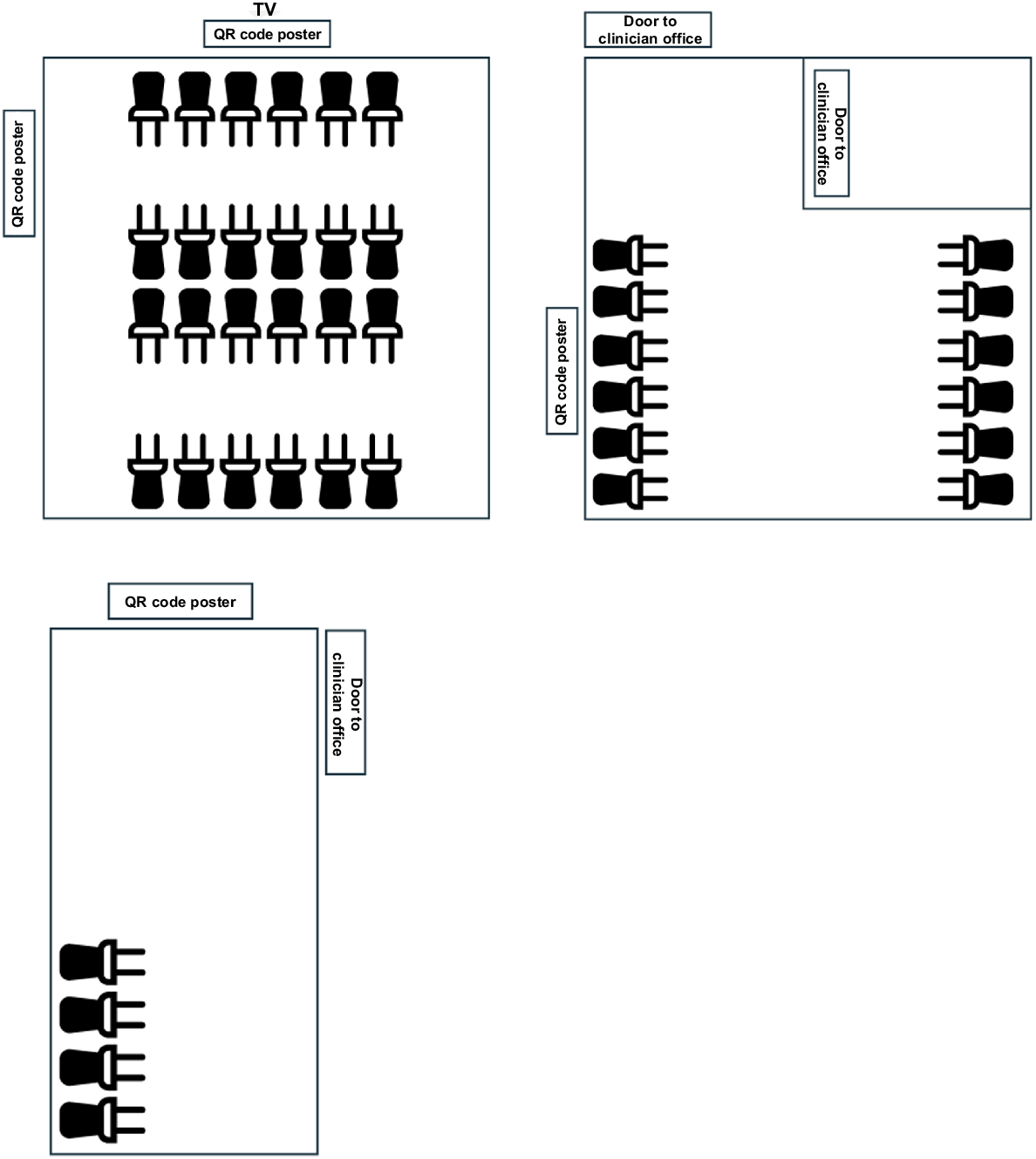

The first study site was a general practice situated within a university, located in an inner north metropolitan suburb of Melbourne, Australia, which primarily serves students and staff attending the university. There is a total of 40 seats in the general practice waiting area split across three zones, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Waiting area of the university general practice and the location of recruitment poster displays.

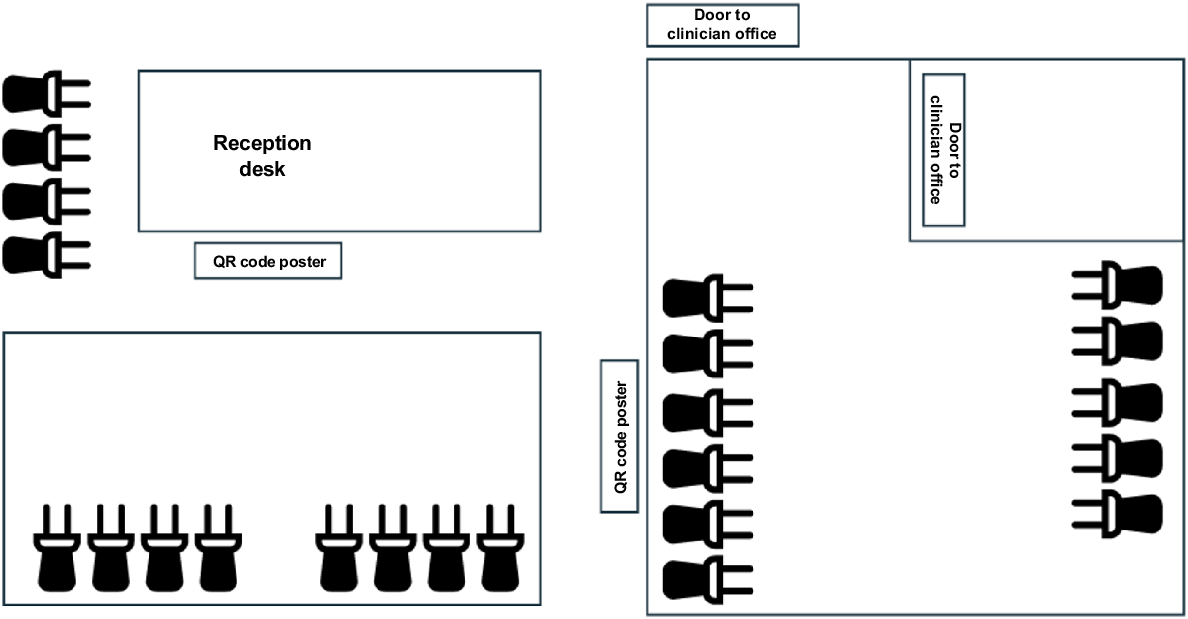

The second study site was a private general practice clinic, located in a south-east metropolitan suburb of Melbourne, Australia, servicing patients across the lifespan (infants to older adults). There is a total of 23 seats in the waiting room area split across two zones, as depicted in Fig. 2.

Participants and recruitment

All individuals, including patients and visitors to the two general practice waiting rooms during the study period, were eligible to scan the QR code displayed on posters and to be added to the cumulative count. Ten colour posters containing the QR code of various sizes (A2 and A3) were placed on the walls of the waiting rooms with a short description of the project and content of the QR code (Fig. 3). Contents of the QR code included resources for healthy diet and lifestyle, including recipe suggestions and informative videos. Full content of the QR code can be found at: https://linktr.ee/healthypeoplehealthyplanet1.

Participants who completed Part 1 (scanned the QR code) were offered a follow up semi-structured interview, which was approximately 20–25 min in duration. Participation in an interview was restricted to individuals aged >18 years who were able to undertake an interview in the English language. Staff at the health services were ineligible to participate.

All interviews were conducted via Zoom, after written informed consent was obtained. Participants were reimbursed a A$20 gift card for their time.

Variables

The primary outcome was the number of scans. There were no secondary outcomes. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, with frequencies reported as numerical counts or percentages. The estimated number of patients exposed to the QR codes in the waiting area was 40 people per day based on the average number of in-person clinic appointments per day during the study period.

Bias

To avoid inducing financially motivated use of the QR code (which may have biased QR code use), financial reimbursement for participating in the study was not advertised on the poster displayed in the waiting area. To minimise potential privacy concerns that may have affected waiting patients’ willingness to scan the QR code and introduced self-selection bias, demographic information was not collected from participants who scanned the QR code.

Study size

There was no set study size for the QR code scans, all scans were recorded during the study period of 1 year. For the semi-structured interviews, the sample size was determined using the concept of information power (Malterud et al. 2016). The concept of information power can be used to guide sample size in qualitative research. In this study, as data analysis progressed and the information power of the dataset was assessed by co-analysts, with oversight from experienced qualitative researchers, the data collected from interviews with a sample of 10–12 participants were deemed to hold sufficient information power to answer the research question.

Data collection

The count of the QR code was facilitated by Linktree, a third-party link management program supporting the health information site. Daily scan counts, unique scans and click-throughs were measured, as well as a lifetime sum of the QR code scans.

Development of the open-ended interview questions (Box 1) was informed by the technology acceptance model (TAM) to assess user experience of accessing digital health resources by scanning a QR code displayed on a poster in a general practice waiting room.

| Box 1.Interview guide and correlation to TAM constructs (in italics) |

| Tell me about your experience in GP waiting rooms – how do you usually spend your time in GP waiting rooms? |

| Why did you decide to scan the QR code in the waiting room? |

| Behavioural Intention to Use (Acceptance) |

| What was your experience of scanning the QR code in the waiting room? |

| Actual Use |

| After you scanned the QR code and the online web page opened, what was your experience of interacting with the health information on your device? |

| Actual Use |

| What are your thoughts on scanning QR codes to access health information in GP waiting rooms? |

| Attitude |

| What are your preferred ways to get health information in a GP waiting room? |

| Prompts: posters, pamphlets, videos |

| Actual Use |

| Did you find it easy or hard to use the QR code? Tell me what made it (easy or hard) for you? |

| Perceived Ease of Use |

| Did you find using a QR code to access health resources useful? Please explain. |

| Perceived Usefulness |

| If you were to see a QR code for health resources in another GP waiting room, would you be willing to scan it? Tell me why. |

| Behavioural Intention to Use (Acceptance) |

| What suggestions do you have for making QR codes more accessible or attractive to scan? |

| That was the last question! Thank you so much for taking time to talk to me. Is there anything else you would like to share that I have not asked? |

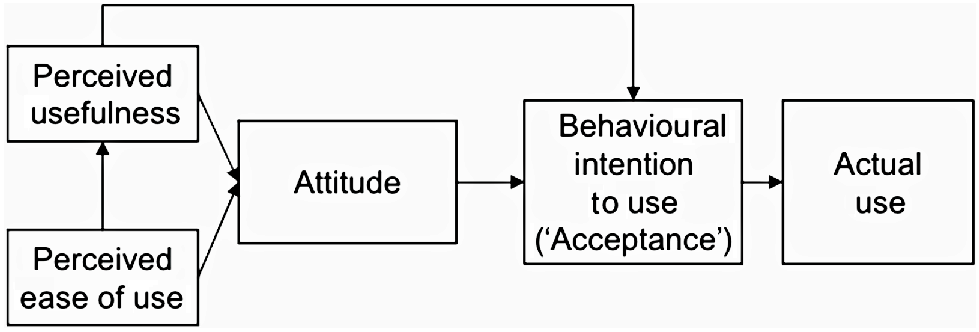

Theoretical framework underpinning interview topic guide

The TAM was used to inform the development of the interview topic guide in this study. The TAM describes the process of adoption of new technology and was first described by Davis in 1989 (Holden and Karsh 2010). The key constructs of the TAM are perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, social influence/subjective norms and perceived behavioural control (Holden and Karsh 2010). The TAM is commonly used in health research to understand user acceptance of new technology (Rahimi et al. 2018; Lau et al. 2023). Using the TAM to inform the interview topic guide helped to facilitate a thorough exploration of factors that may affect the perceptions of users presented with new technology, and influence whether they accept and use that technology. In this study, the ‘new technology’ available for users was a QR code available for scanning in the waiting area that enabled access to web-based health information.

Fig. 4 provides a visual summary of the TAM.

Demographics data were also collected for age range (e.g. 25–27 years) and gender (male/female/other) at the end of each interview. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team (EH, PJ, YZ).

Statistical methods for data analysis

The QR code scans were collated automatically using an online data analytics platform called Linktree, which generated a sum of all unique scans that occurred between the set dates of October 2022 to September 2023.

Analysis of the interview data was performed at the same time as data collection by the same researchers (EH, PJ, YZ), with input into coding and theme development by an experienced qualitative researcher (CM) through research team meetings. Interview transcripts were imported into NVivo 14 Windows software for analysis (Lumivero, https://lumivero.com/resources/free-trial/nvivo). Interview data analysis was informed by Lochmiller’s thematic analysis approach (Lochmiller 2021). An exploratory, inductive approach using thematic analysis was taken, followed by deductive analysis using the TAM theory and coding data as ‘barriers’ or ‘enablers’.

Results

Part 1: QR code scan

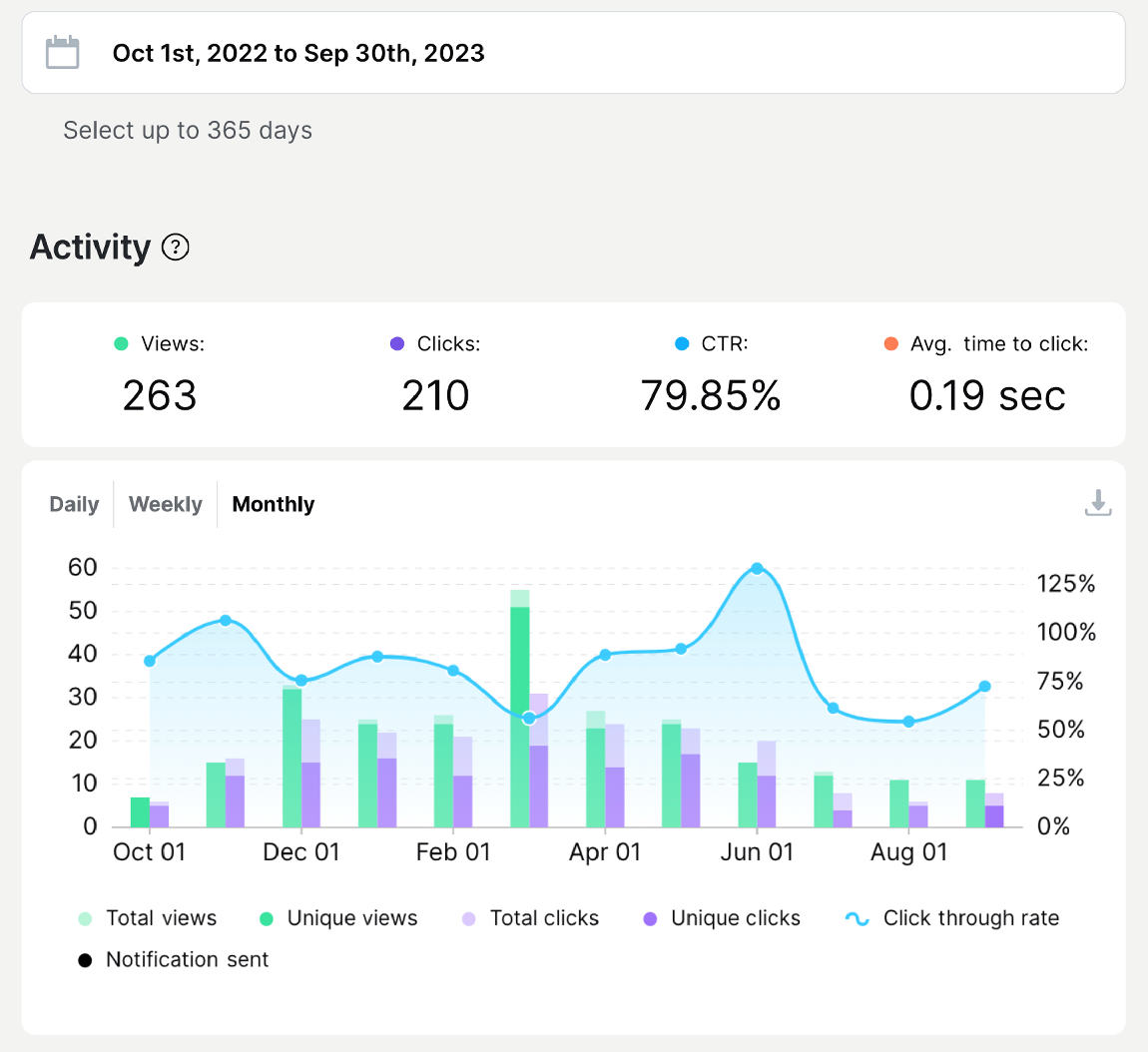

A total of 263 scans were recorded during the study period. Monthly breakdown of the QR code is provided in Fig. 5. A total of 210 click-throughs were recorded, meaning 210 participants engaged with the subsequent health information material included in the QR code. April 2023 was the month corresponding to the most scans. We found that our QR code received regular engagement during the recruitment period, and the periods of time when no QR codes were scanned correlated to the periods when the GP clinic was closed for holidays (25 December 2022–3 January 2023; and 15−19 April 2023).

Part 2: follow-up semi-structured interviews

Twenty participants expressed interest to participate in a follow-up interview. All interview participants were recruited from the university clinic. However, eight participants were lost to follow-up, as they did not respond to contact attempts. Participants (n = 12) were mostly women (n = 10). The age range of participants was 18–50 years, the majority were aged <30 years (n = 9). Interviews were facilitated by EH (MD), PJ (MD) and YZ (MD) (Table 1).

| Participant | Age range (years) | Occupation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30–35 | PhD student | |

| 2 | 25–27 | PhD student | |

| 3 | 21–24 | PhD student | |

| 4 | 25–27 | PhD student | |

| 5 | 50+ | University staff | |

| 6 | 35–40 | PhD student | |

| 7 | 21–24 | Masters student | |

| 8 | 21–24 | Masters student | |

| 9 | 27–30 | PhD student | |

| 10 | 18–21 | Undergraduate student | |

| 11 | 40–45 | PhD student | |

| 12 | 25–27 | PhD student |

Thematic findings

From the first round of coding, 39 unique codes were identified. After iterative discussion and recoding, we refined the codes to 29 categories. From this, 11 themes were identified, summarised below with salient quotes. These 11 themes could grossly be classified into two broad categories – ‘Facilitator’ or ‘Barrier’ – which resulted in six ‘Facilitator’ themes and five ‘Barrier’ themes.

Many participants reported being curious in the leadup to scanning the QR code in the waiting area. They expressed curiosity in the code design, the content within, the technology itself, as well as in the study.

Yeah absolutely, I’m very curious by nature, so I will have a look because I want to see people’s research and what the information is. (Participant 11)

That’s when I saw the QR code, I was curious to know what is there inside. (Participant 10)

Many participants reported feeling bored in the waiting area before an appointment due to the waiting time. One participant also noted that QR codes were a welcome distraction from the anxiety they were experiencing.

Because I was bored. I was looking around and couldn’t see anything to read. Do feel bored when waiting. (Participant 5)

When you go and see a GP, you are kind of anxious and restless as well, not relaxed. (Participant 9)

Participants felt that QR codes were an effective way of communicating sensitive health information; for example, on the topic of sexual health.

Having a QR code affords you some anonymity. (Participant 12)

I think, sometimes with brochures, if you’re like interested in sensitive or stigmatised stuff like STIs, for example, you don’t want to hold a brochure of that in the waiting room, you don’t want that associated with you. (Participant 12)

Many participants attributed the challenge of scanning to the small size of the QR code and the location was far away from where they were seated.

[I couldn’t reach it] So I had to stand up and approach the poster. (Participant 2)

If [the size of the QR code is] too small for the users, the moment it’s not super convenient they’ll just give up and not bother accessing it, unless it’s something that’s really important for their visit that day. (Participant 8)

Many participants did not complete all the content within the QR code before they were called in for their appointment.

By that time, I was already called in by the GP, so I didn’t end up downloading the content. (Participant 12)

Almost all participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed them to using QR codes.

I feel like everyone’s pretty used to scanning it at this point, because we all did it during the pandemic for a variety of reasons. (Participant 12)

Most participants suggested that only using QR codes will exclude members of the community who are technologically illiterate. Several participants suggested that not owning a ‘smart’ mobile phone equipped with a camera is a significant barrier to engaging with QR codes.

I think there’s a potential to exclude certain populations who you know have barriers to digital health, or digital access anyway. (Participant 10)

My mother-in-law has no mobile phone and doesn’t want to get one. (Participant 3)

Many participants felt that the older population may prefer physical forms of health information, such as brochures or pamphlets. However, one participant from a younger age group commented that the ability to take away physical paper pamphlets to view later was also convenient. Contrastingly, another participant believed that physical leaflets will only be misplaced. When asked what their preferred method of health information attainment in the waiting area were, participants still elected to retain physical formats.

A lot of older people like my parents prefer taking physical hard copies of things, rather than digital copies. (Participant 12)

Preference wise, personally I would prefer pamphlets. (Participant 9)

Participants felt that QR codes could potentially be untrustworthy. The majority of concerns were around privacy and the potential for data breach. Contrastingly, one participant felt reassured, because the location of the code was inside a GP waiting room.

If its inside the GP clinic, I’d say it’s a bit more trustworthy. I think it’s a good idea. (Participant 2)

Many participants wished to save the page associated with the QR code to revisit the content later. Some participants even suggested incorporating a feature to open the content link in a permanent tab in the Internet browser to retain the content.

To be fair, the QR code was really good for me. Because I don’t have to read it there and then, I can go later and read it later, if you have a load of leaflets, it gets thrown away or misplaced. (Participant 5)

Or if there’s a way to scan the code and a way to copy the link somehow, so that it will kind of save onto the device temporarily, so that you can paste it to the browser, so you don’t lose it later on. (Participant 8)

Many participants who were younger said that the use of QR codes is an environmentally friendly option to promote health information, and is less wasteful than paper brochures and pamphlets.

I feel like this is obvious, but also the fact that it is just less paper, it’s brilliant. Much less waste, obviously you need to print out the QR code, but way less than having loads of leaflets lying around. (Participant 5)

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the uptake of QR codes in health service waiting rooms to access web-based health information, as well as to explore the user experience of using QR codes for that purpose.

Our data are congruent with both criteria of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in the TAM (Holden and Karsh 2010). However, in the context of providing health information in clinic waiting rooms, our qualitative evidence demonstrates that although patients appreciate the availability of information via QR codes, there remain concerns and barriers.

Overall engagement with QR codes was low. This is demonstrated by the 263 scans and 201 click-throughs to engage with the content of the code despite a recruitment period of a year. Based on 40 appointments per day for each clinic, this means that there is only approximately 21 click-throughs for every 1000 in-person appointments, and less than one click-through per day across the two clinics. This low engagement may be multifactorial and is further explored in each of the sections below.

Intention to scan

Curiosity about the QR code, and boredom or anxiety while waiting for an appointment were motivators for patients to scan the QR code. At the same time, time before appointment was also identified to limit engagement with the content. Given that there is generally an average wait time of 30 min in Australian general practices (Motio 2022), such novelty presentation of health promotion in the waiting area setting of health services could be an opportunity. Conversely, it is also possible that the time waiting before an appointment was low, limiting exposure time, which may be a contributing factor to the low engagement of QR codes in this study.

Increased familiarity with QR codes from the recent COVID-19 pandemic

Our results found that the pandemic has increased familiarity with using QR codes. Given governmental mandates of check-ins, where individuals were required to scan QR codes to record visits in public in Melbourne, Australia, it is expected that members of the community are likely to have had increased exposure to QR codes in everyday life since 2020. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the exponential increase in use of QR codes during the pandemic and in the post-pandemic era (Nove 2023).

Perceived ease of use of the QR code

All interview participants reported that the process was easy. Barriers identified with scanning included the suboptimal size and location of the poster. This is postulated to be one of the contributing causes to the low engagement with the QR codes in this study. Posters that were too far away or required the participant to stand up and walk towards the display were a barrier to engagement. This suggests that the location of the QR code may be crucial for uptake and engagement. Our finding is in line with existing literature where the location of the health information or advert directly impacts reach (Han 1992). To address this, health services wishing to display and disseminate information using QR codes could observe visitors in their waiting room to identify locations of high visibility and convenience to facilitate maximum reach. A future study could collect observational data to clarify implementational issues.

Perceived benefits of the QR code

The environmental sustainability benefit of utilising QR codes to disseminate information seemed to be important to participants, particularly those who were younger. This reflects the general views of young people of the environment and climate change in the published literature (Ballew et al. 2019; Poortinga et al. 2019). It is also possible that participants found the contents of the QR code to be not interesting and chose not to engage with the QR code in the first place. Similarly, those who found the content interesting may have saved the QR code and have revisited the code after the initial scan.

Anonymity of viewing the health information content, especially sensitive topics, was another advantage of the QR code. Confidentiality in sexual health is identified as a significant priority for individuals, and anonymous assessments in sexual health are associated with improved data quality in surveys and questionnaires (Durant et al. 2002; Garside et al. 2002). Given the benefits of anonymity of QR codes, sexual health promotion and engagement could be delivered through this mode in waiting areas.

Perceived barriers to using the QR code

In our study, all participants for the semi-structured interviews were recruited from the university clinic. This may mean that the university population may be a more tech-responsive group than the community clinic.

Although it is estimated that 85% of the global population owns a smartphone with the capacity of scanning a QR code, this does still exclude members of the community who do not own a smartphone (Howarth 2023). To ensure that these individuals do not miss out on health information dissemination, clinics and health services must continue to retain multimodal resources, such as physical posters and displays, alongside digital options.

Some participants suggested that older adults would prefer physical forms of health information, given their relative inexperience with technology. Considering our increasingly aging Australian population, with 16.2% of individuals over the age of 65 years, understanding preferences and patterns for health information and resources will be crucial to ensure equitable access (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023).

Although all participants had a positive experience with the QR codes in the waiting room, some participants still voiced their preferences of retaining physical forms of health information. A few participants also stated that they preferred multiple formats, including digital and physical. This is reflected in the literature, where individuals preferred a variety of methods for health information engagement (McDonald et al. 2021). Health services and clinicians should consider disseminating multiple forms of the same information to ensure greater reach to all audiences.

QR code safety

Privacy and security concerns are other major barriers to QR code engagement. Participants voiced their worries regarding insidious data collection from their device from scanning the QR code. Malware, ransomware or Trojan horses could be linked to QR codes, where users may accidentally download and compromise their privacy and data security. With the increased incidence of Internet scams in Australia, with two-thirds of all Australians being exposed to a scam in a 1-year period, measures should be taken to prevent vulnerable members of the community from being exploited for malicious intent (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023). Other risks that clinics must consider include click-jacking, which is when another QR code is pasted on top of the original QR code (Thompson and Lee 2013). Endorsement and thorough exploration of the information linked to the QR code should be performed on a regular basis to safeguard patients and visitors to the waiting area.

Although our study did not investigate the efficacy of health behavioural changes with the involvement of clinicians, it is reasonable to assume that clinician-led discussions may be beneficial for health promotion, and behavioural and outcomes changes. An English study found that patients wanted and expected to receive information from their GPs about behavioural changes, and were more likely to implement recommendations when received directly from their GP (Keyworth et al. 2020).

Suggestions to improve the QR code

Many participants suggested the addition of a feature to save the link to revisit in the future to improve the QR code experience. Some participants in our study had used a downloaded third-party QR code scanner rather than their default camera application on the smartphone. Although some QR code scanner applications will open the QR code link in a new tab on their default Internet browser, some applications will open a temporary page that is lost once the user exits the camera application (Zhan 2020). This issue can be overcome if participants use their default camera application to scan the QR code. However, individuals using an older version of an operating system, such as older generations of iOS, the operating system for Apple devices, the default camera will not be able to read the QR code and will require a third-party QR scanner. Older Apple devices that are unable to be upgraded to iOS 11 are, therefore, unable to open the linked QR code webpage in a new tab. Although it would be inappropriate to encourage users to purchase or upgrade their devices for this desired process to automatically occur, the QR code design could include an option to copy the webpage link for individuals to save and read later.

Another suggestion to improve QR code engagement was its location and size. It will be pertinent to design the QR code to maximise visibility for visitors. In marketing, advertisements that are larger in size are given greater attention when compared with smaller sized advertisements (Han 1992). Likewise, in healthcare marketing and promotion, the location of the promotion material will directly influence the scan engagement. Those seeking to engage visitors in healthcare waiting spaces must consider the location of the QR code to maximise coverage.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. The timing of the study period included major public holidays and school holiday periods, therefore hampering recruitment. Given our participants were mostly from the 21–35 years age range, with only one participant above the age of 50 years, the findings cannot be extrapolated to the general community. However, this is expected, given that one of the research sites was at a university health service, which predominantly serves students and staff of the university. Precise numbers of patients and visitors to the waiting areas of the two clinic sites were not counted during the study period, so scan rates are estimates based only on patients attending. We also acknowledge that participants who view QR codes with more favourable opinions are more likely to engage with our study than those who mistrust or have negative views towards the QR codes, as they would not engage with the QR code in the first place. We did not interview informed observers, such as clinic reception staff, who may have provided insight into reasons why individuals did not engage with the QR code. Our study also missed recruiting individuals from deprived backgrounds, as demographics data suggested all participants had a higher level of education, and therefore assuming a higher level of literacy.

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence and popularity of QR codes within the community, harnessing this technology to communicate health information is a novel and engaging way of delivering health content. We found several facilitators and barriers to using QR codes to engage patients and visitors with health information material in health service waiting area.

Future research is needed to explore the use of QR codes in settings other than general practice and in the broader community. Interviewing clinic staff members or those who did not engage with the QR code would be a useful next step for research, to further understand perceptions of and barriers to engaging with QR codes in GP clinic waiting areas. Gathering observational data would also allow clarification of implementational issues. Recruiting participants from diverse social and educational backgrounds in future studies would be beneficial. Similarly, studies investigating age group preferences may be useful to tailor information giving to desired demographics. Strategies to effectively utilise QR codes as a mean to deliver health information swiftly and sustainably should be investigated.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

Funding was received from the Wattle Fellowship Scholarship from the University of Melbourne to support participant reimbursement for the semi-structured interviews.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding received from the Wattle Fellowship Scholarship from the University of Melbourne. Special thank you to Raymond Wu, Bethanie Chong, Purab Patel, Evangeline Ginnivan, Amin Abedini, Toni Zhang, Bernice Wang, Michael Barrese, Hugo Klempfner, Akshan Pathmaraj, Zhouai, Dawoud Al-Mekhled, Angelo Kim and Allen Xiao for their assistance and support in creating the content of the QR code. Thank you to managers Anne McGlashan and Dr Joan San for your support.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023) 13.2 million Australians exposed to scams. ABS, Canberra. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/132-million-australians-exposed-scams [accessed October 2023]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Older Australians. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians [accessed October 2023]

Ballew M, Marlon J, Rosenthal S, et al. (2019) Do younger generations care more about global warming. Available at https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/do-younger-generations-care-more-about-global-warming/

Berkhout C, Zgorska-Meynard-Moussa S, Willefert-Bouche A, Favre J, Peremans L, Van Royen P (2018) Audiovisual aids in primary healthcare settings’ waiting rooms. A systematic review. European Journal of General Practice 24(1), 202-210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Durant LE, Carey MP, Schroder KEE (2002) Effects of anonymity, gender, and erotophilia on the quality of data obtained from self-reports of socially sensitive behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 25(5), 439-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Garside R, Ayres R, Owen M, et al. (2002) Anonymity and confidentiality: rural teenagers’ concerns when accessing sexual health services. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 28, 23-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Han JK (1992) Involvement and Advertisement Size Effects on Information Processing. Advances in Consumer Research 19, 762-769.

| Google Scholar |

Holden RJ, Karsh BT (2010) The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 43(1), 159-172.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Howarth J (2023) How many people own smartphones? (2023–2028). Available at https://explodingtopics.com/blog/smartphone-stats [accessed October 2023]

Jansen CJM, Koops van ‘t Jagt R, Reijneveld SA, van Leeuwen E, de Winter AF, Hoeks JCJ (2021) Improving health literacy responsiveness: a randomized study on the uptake of brochures on doctor-patient communication in primary health care waiting rooms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(9), 5025.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Karia CT, Hughes A, Carr S (2019) Uses of quick response codes in healthcare education: a scoping review. BMC Medical Education 19(1), 456.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Keyworth C, Epton T, Goldthorpe J, Calam R, Armitage CJ (2020) Perceptions of receiving behaviour change interventions from GPs during routine consultations: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 15(5), e0233399.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lau P, Tran MT, Kim RY, Alrefae AH, Ryu S, Teh JC (2023) E-prescription: views and acceptance of general practitioners and pharmacists in Greater Sydney. Australian Journal of Primary Health 30,.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lochmiller CR (2021) Conducting thematic analysis with qualitative data. The Qualitative Report 26(6), 2029-2044.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD (2016) Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26(13), 1753-1760.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McDonald CE, Remedios LJ, Said CM, Granger CL (2021) Health literacy in hospital outpatient waiting areas: an observational study of what is available to and accessed by consumers. HERD 14(3), 124-139.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McDonald CE, Voutier C, Govil D, D’Souza AN, Truong D, Abo S, Remedios LJ, Granger CL (2023) Do health service waiting areas contribute to the health literacy of consumers? A scoping review. Health Promotion International 38(4), daad046.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Motio (2022) Motio revolutionizes the medical practice waiting room experience. Available at https://www.motio.com.au/motio-revolutionizes-the-medical-practice-waiting-room-experience/ [accessed December 2023]

Nove (2023) Detailed statistics report: QR code usage worldwide before and after Covid-19. Available at https://www.qrcode-tiger.com/qr-code-statistics-before-and-after-covid-19#QR_code_Covid-19_statistics_report_Usage_after_Covid [accessed October 2023]

Penry Williams C, Elliott K, Gall J, Woodward-Kron R (2019) Patient and clinician engagement with health information in the primary care waiting room: a mixed methods case study. Journal of Public Health Research 8(1), 1476.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Poortinga W, Whitmarsh L, Steg L, Böhm G, Fisher S (2019) Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: a cross-European analysis. Global Environmental Change 55, 25-35.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rahimi B, Nadri H, Lotfnezhad Afshar H, Timpka T (2018) A systematic review of the technology acceptance model in health informatics. Applied Clinical Informatics 9(3), 604-634.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rodrigue E (2021) What is a QR code + how does it work? Everything marketers should know. HubSpot. Available at https://blog.hubspot.com/blog/tabid/6307/bid/16088/everything-a-marketer-should-know-about-qr-codes.aspx#:~:text=A%20QR%20code%20works%20similarly,This%20transaction%20happens%20in%20seconds [accessed October 2023]

Sharara S, Radia S (2022) Quick response (QR) codes for patient information delivery: a digital innovation during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Orthodontics 49(1), 89-97.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thompson N, Lee K (2013) Information security challenge of QR codes. Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law 8(2), 2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zhan Z (2020) iOS Closes web page opened by camera QR scan when quit. Stack Overflow. Available at https://stackoverflow.com/questions/61096209/ios-closes-web-page-opened-by-camera-qr-scan-when-quit [accessed November 2023]