History and establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve

G. R. Chatfield A and Denis A. Saunders B *

B *

A

B

Abstract

This paper sets out the events leading to the establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

This paper is based on research into literature relating to the Albany region, government files and oral accounts relating to the area.

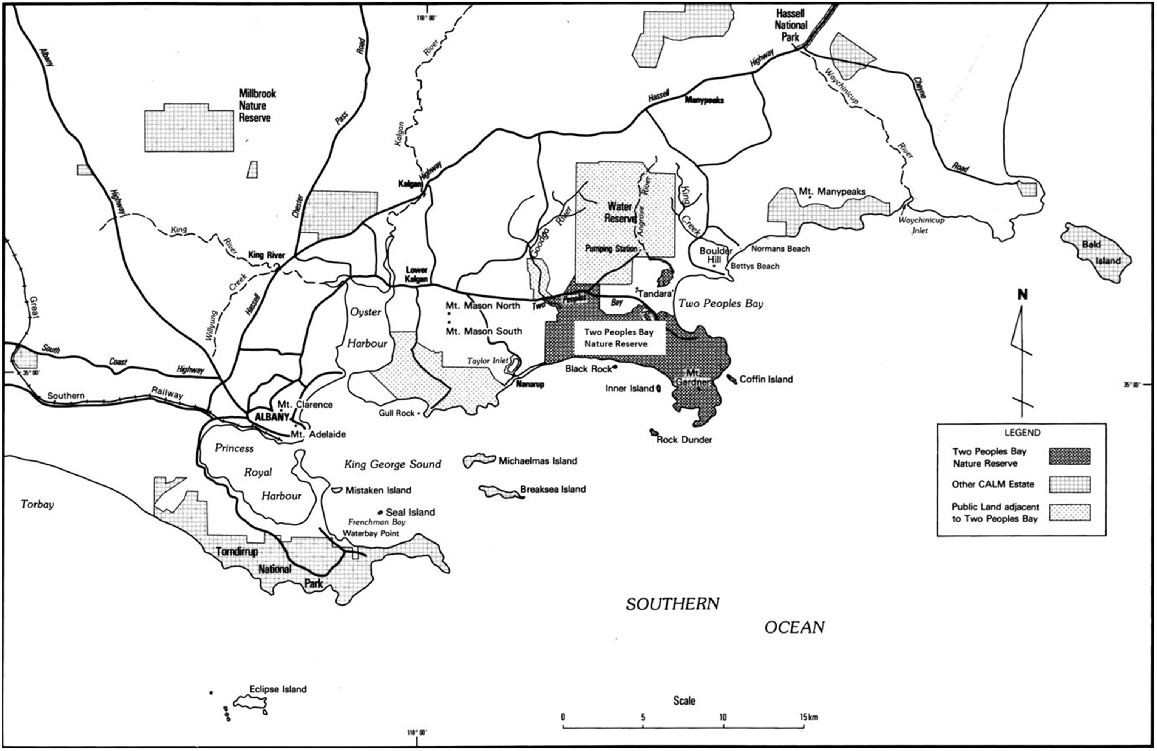

Long known to the Noongar peoples, Two Peoples Bay was first mapped by Europeans in 1791 by Captain George Vancouver. The area was rapidly established as a base for the over-exploitation of natural resources. As the region became more developed and human population increased, recreational pressure on the area was such that the Western Australian Government surveyed Two Peoples Bay to establish a townsite. Just before the final surveys for the townsite were completed, the supposedly-extinct noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus), was rediscovered there. National and international pressure on the WA Government from the conservation movement resulted in the reversal of the decision to develop a town in the area and led to the establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1967.

The establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in the face of pressure for the development of a town on the bay, provides an interesting example of the needs of nature conservation over-riding real estate development.

Although nature conservation values rarely stop real estate development, the Two Peoples Bay example demonstrates that nature conservation may prevail over real estate development, in this case involving the rediscovery of a species believed extinct.

Keywords: conflicts over townsite and nature conservation, noisy scrub-bird Atrichornis clamosus, Western Australian sealing, Western Australian whaling, Western bristlebird Dasyornis longirostris.

Introduction

Any person perusing a map of south-western Australia will become aware of the multi-national heritage of the area from the various names of coastal features. The first European explorers and merchants named the coastal features as they became known to them. First one nationality, then another, would name sections of the coast, so that today the different languages of the names are intermingled along the coast. However, the present names do not demonstrate the mixture of their national origins. Examples in the vicinity of King George Sound, on the south coast, include Kalgan River which was originally named Rivière des Francais and Two Peoples Bay, the subject of this history, was Anglicised from the French Baie de Deux-Peuples.

The subjects covered in this paper are varied. The early explorers and exploration, and the rivalry between and within various exploration parties, are covered first. The arrival of the sealers and whalers, from overseas and local settlements, influenced the course of Two Peoples Bay’s history, as did the establishment of the Albany settlement. More remote, but nonetheless significant in its influence on the history of the area, were foreign and defence policy decisions made at Westminster, in the United Kingdom. Debates on the rights of British subjects versus those of foreign nationals affected the bay’s development, as did local decisions on such things as the construction of railway lines in the Albany area. Matters of recreation and holiday leisure activities became a focal point later in the history of the bay, to be dominated after 1961 by the issue of conservation, particularly of the noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus), a near-extinct species.

The topics in this history are representative of issues and events that shaped Western Australia’s history and development, in particular the coastal areas and especially those of the south-west coast. A greater understanding of the history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve will help in the development of policies that will conserve the area for future generations, and provide effective management of those areas already committed to conservation.

Discovery and exploration by Europeans

Early European explorers

Descriptions of prominent coastal land forms as seen from seaward were essential to early maritime explorers. By recognising a described feature, a captain was able to establish his position on an uncharted coast. Knowing his position, a ship’s captain could determine other information, such as the relative proximity of safe anchorages, watering and timbering points, and reefs and shoals.

In September 1791, Captain George Vancouver named and described one such prominent feature at Two Peoples Bay; the high cone-shaped Mt Gardner to the east of King George Sound. When sailing eastward from there, Vancouver did not stay close in shore and failed to notice the small, sheltered bay immediately north of Mt Gardner (Vancouver 1967).

Matthew Flinders provided the first recorded sighting of the bay when, in the Investigator, he surveyed King George Sound in December 1801 and January 1802. In April 1801, he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks (Austin 1964): ‘My greatest ambition is to make such a minute examination of this extensive and very interesting country that no person shall have occasion to come after me to make further discoveries.’

Though not specifying any person, there is no doubt that Flinders had in mind the French expedition under the command of Nicolas Baudin, which also had the mission of charting and exploring the coast of north, south, and west Australia. Flinders had previously commented to Banks: ‘I fear a little longer delay will lose us a summer and lengthen our voyage at least six months; besides the French are gaining time upon us.’ On 5 January 1802, Flinders, in his haste to discover as much of the coast as possible before his French rivals, sailed from King George Sound toward the Recherche Archipelago and noted in his journal:

Mount Gardner is a high, conic-shaped hill, apparently of granite, very well delineated in Captain Vancouver’s atlas. It stands upon a projecting cape, which the shore falls back to the northward, forming a sandy bight where there appeared to be shelter from western winds; indeed, as the coastline was not distinctly seen round the south-west comer of the bight, it is possible there may be some small inlet in that part. (Flinders 1966)

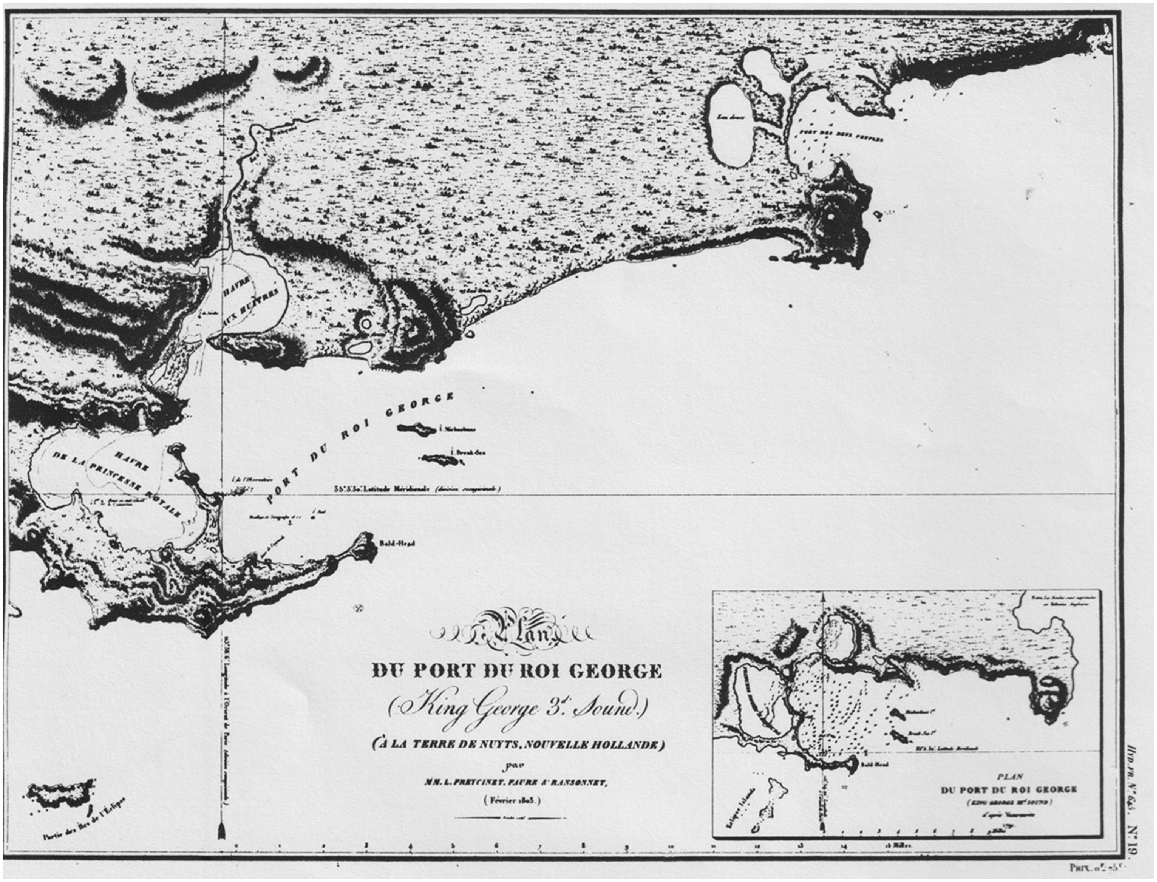

It is ironic, in view of Flinders’ comment to Banks, that the sandy bight sheltered from western winds he described should be minutely examined and named the following year by the French expedition (Fig. 1).

Chart of the King George Sound – Two Peoples Bay area prepared in 1803 during the Freycinet exploration of the coast.

On the morning of 17 February 1803, Captain Nicolas Baudin was sailing toward King George Sound in the corvette Geographe. He surveyed the channel between Bald Island and the mainland, then continued west. Baudin (1974) noted:

…we saw several inlets along the coast to Mt Gardner which seemed to indicate that there might be some good shelter there. I did not go investigating them with the ship, but resolved to have them examined in detail by one of my boats as soon as we were in a safe place. I also pointed out to the officer for whom I intended this work the parts that I considered of greater importance… (Baudin)

That evening Baudin anchored the Geographe between Seal Island and Frenchman Bay, just east of Waterbay Point, where Vancouver had noted a watering-place (Fig. 2). On 20 February, Baudin dispatched two boats to survey sections of the coast. The larger boat under the command of Midshipman J. J. Ransonnet was to:

explore the portion of the coast between Vancouver’s Mt Gardner and d‘Entrecastreauxs Bald Island. It seems to me that it is particularly useful to know it in detail, as it offers a view of various inlets which could hold resources or a haven in bad weather for the future navigators in these regions. Generals d’Entrecastreaux and Vancouver only saw the coast from a distance; you are going to examine it closely and with scrupulous attention. You will enter all the inlets along it and explore each one in detail. If, as I am inclined to believe, you find some ports there, you are to survey them, take soundings and determine as exactly as possible the points that form their entrances. (Baudin 1974)

The second boat, under the direction of the geographer P. Faure and commanded by Midshipman Charles Baudin, was to survey King George Sound, Princess Royal Harbour, and Oyster Harbour, as well as the coast as far as Mt Gardner.

Ransonnet (1803) completed his task by 27 February. In his report to Commander Baudin, he indicated that he was not the first to enter the bay north of Mt Gardner. On doubling Cape Vancouver and sailing past what is now called Coffin Island, he noted:

At one o’clock being at the opening of a bay, I found, when we moored, a building towards which we advanced. The Captain, P. Jane Pendleton commanding the Brick [sic], of the American Union, welcomed and informed me that he had been in the bay two days, four months after their departure from New York and that the object of his trip was to look for some pelts that he wished to sell to China. (Ransonnet)

Having informed the Americans of Baudin’s presence in King George Sound, Ransonnet continued his survey of the bay. In the meantime, Captain Pendleton weighed anchor and sailed to meet Baudin. He arrived to find Baudin away on his own survey. On 24 February, Baudin and Pendleton dined together, and, at Pendleton’s request, Baudin provided him with charts of the New Holland coast and information regarding sealing there (Baudin 1974).

Although there is no mention of a name for the bay in Ransonnet’s report, his meeting with the Americans was commemorated in the naming of the bay. It was Louis Freycinet, who was part of the expedition as commander of the Casuarina, who credited Ransonnet with proposing the name, Baie des Deux-Nations, in memory of the friendly encounter there with the Americans (Peron and Freycinet 1818). Relations between Baudin and Freycinet were, however, less than friendly, and their rivalry has led to conflicting accounts of the naming of the bay (Henn 1934; Charnley 1955; Webb 1963; Marchant 1982). On the chart drawn for Freycinet, Faure, and Ransonnet (Fig. 1) the name is given as Port des Deux-Peuples. The Anglicised form of the name became Two Peoples Bay.

The significance of the name, Two Peoples Bay, was soon lost to the international community as demonstrated by the comment of a young American whaler who came to the bay in 1849: ‘This bay is named Two Peoples, for what reason I know not, for not a soul lives here, nor is there any house to be seen’ (Haley 1951).

Further exploration of the south coast continued with Lieutenant Phillip Parker King in 1818 and Captain Dumond D’Urville, who was at King George Sound in 1826. On 12 October, D’Urville met two parties of sealers, six of whom had been marooned on Coffin Island, and on 17 October he noted two whalers in the vicinity. The sealers and whalers who were to dominate the history of Two Peoples Bay for the next 50 years were present in the area before any official settlement was established. With D’Urville’s departure on 25 October 1826 and the arrival of Major Edmund Lockyer two months later, the period of transient exploration ended. The New South Wales colony outpost at Albany was established and developed, and subsequently there occurred a corresponding growth of the sealing and whaling industries; part of these being focused on Two Peoples Bay.

The sealers

The two sealing gangs noted by D’Urville in October 1826 were still in the vicinity of King George Sound when Lockyer arrived in December; one group was based on Eclipse Island, the other to the eastward (Watson 1921). The presence of these sealers and their relationships with the local Aboriginal population were a concern for Lockyer in the early days of the establishment of Albany. Lockyer also noted that the continued, uncontrolled exploitation of the fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) population would cause the industry to become valueless, as the depletion of the fur seal population would effectively reduce profitability. In a dispatch to the Colonial Secretary of New South Wales he recommended that:

a prohibition should be immediately given against any Individual taking the seals or going at all to the Islands, the Government claiming them as part of the Territory and once in Three Years to Farm the Islands out for the season from November to the end of April following, or such other months as would be found not to interfere with their breeding or the time they shed their Fur. (Lockyer)

The Major’s recommendation was not acted on and sealing continued at a greater rate as settlers of the new colony, hoping to supplement their incomes, joined the ranks of sealers.

Lockyer’s prediction that over-exploitation would jeopardise the industry was confirmed in 1831 by surgeon and explorer Captain Alexander Collie. Upon accompanying a sealing gang of settlers from Albany to an island off Mt Gardner he identified as Coffin Island, on 4 June 1831, Alexander Collie wrote:

That seal have come up and been killed in considerable numbers at one time, is confirmed, in addition to oral information, by the skeletons which still remain; but none of the party saw any alive at this time. (Cross 1833)

Collie’s journey to Coffin Island provided further information on Two Peoples Bay. He crossed from Coffin Island to the mainland and climbed to the top of Mt Gardner. There he briefly described the soils and vegetation of the area, commenting that he planted almond, castor oil, and other seeds. One of the sealing gang had planted a variety of flower seeds on Coffin Island. From the summit of Mt Gardner, Collie described the surrounding area, noting several lakes, ‘the nearest and apparently largest communicating by a winding channel with the bay to the N and NE… it is said to be brackish’ (Collie in Cross 1833). This is Gardner Lake, which had been put on the chart by Ransonnet in 1803.

Sealing in Two Peoples Bay appears to have become less frequent from the mid-1830s, while the more capital-intensive whaling became the dominant activity in the bay for the next 50 years. Collie in Cross (1833) in fact mentioned that ‘several whales [black] were observed at a short distance off [Coffin Island]’.

Bay whaling

Two Peoples Bay began a long association with whaling during the 1837 season when Captain Francis Coffin of the Samuel Wright established the first whaling station there. How Coffin came to set up his station in Two Peoples Bay is important to understanding the later use made of the bay by other international whalers. On 24 March 1837, the Samuel Wright arrived in King George Sound, 120 days out of Massachusetts, USA. For a month Captain Coffin stayed in the harbour refitting, replenishing supplies, and seeking to employ more hands for the approaching season. He also contacted the settlement’s merchants with whom he hoped to trade in whale bone and whale oil.

The issue of British subjects’ rights to monopolise the whaling industry had been simmering for some time and was inadvertently brought to the boil by Captain Coffin. While attempting to increase his crew he signed on a young man, Andrew Newberry. It so happened that a group of settlers had previously signed up Newberry for their whaling enterprise situated at Doubtful Island Bay about 130 km north-east of Two Peoples Bay. The loss of an employee at a time when labour was scarce provoked Mr. T. B. Sherratt, one of the partners of the Doubtful Island Bay enterprise, to seek official assistance to stop Coffin from whaling at Doubtful Island Bay, as Coffin intended to do. Sherratt made two appeals; one to the Colonial Secretary, the other to the Commander of H. M. Sloop Friton, which was in harbour at the time. In both letters he sought to define the rights of a British subject regarding foreign interference to trade.

Sherratt was impatient to act to prevent competition at his whaling station. Using the information from Commander Crozier of the Friton he wrote to Coffin on 7 April 1837:

I acknowledge the receipt of your communication of yesterday to allow one to say that in this far country the attention evinced [sic] by you is highly gratifying, and I beg to return you my best acknowledgements for the same and to assure you that it is my most sincere wish that there be no need to put the Laws in force – but should unhappily our Fisheries be disturbed or my co-partners annoyed in the prosecution of an undertaking I shall be compelled to call for the protection due to a British subject. (Sherratt)

The threat was plain enough, and the force was immediately present to back it up. Whether it was the threat, or simply that Coffin required a non-hostile population at Albany with which to trade, the result was that Coffin did not go to Doubtful Island Bay. Instead, he established himself at Two Peoples Bay which was at that time unused by the European settlers (Wace and Lovett 1973). It was not long before the American was joined by other American and French whalers in the bay (McNab 1913), again giving the original meaning to its name.

There is a small and protected, gently-sloping, sandy beach between the main beach and South Point at Two Peoples Bay. Behind the beach there is a well-shaded gully where a small stream runs during the winter months. It was on this protected beach and gully that bay whaling at Two Peoples Bay was centred, the whales being flensed on the beach with the try-pots being set up in the gully area.

At this time, whaling was a major income-earner for those nations that were rapidly mechanising. To protect their interests the French sent a man-o-war to the south coast of Australia to safeguard French whalers (Glover 1953).

Although the British subjects of Albany were concerned with their rights, they were also preoccupied with making a living. The foreign whalers provided a focus for a whole range of small enterprises which supported them. Mutton-birders, kangaroo-hunters, vegetable-growers, and traders were all involved in some way in supplying the foreign whaling ships. Merchants and traders in particular developed close links with the whalers, trading in bone and oil as well as being ship chandlers.

Francis Coffin established contacts with Albany’s merchants at the outset. Coffin’s provocation of Sherratt, however, obliged him to carry out his trading with George Cheyne, one of Sherratt’s strongest competitors. This trade, between Cheyne and the Americans and French at Two Peoples Bay, began in 1837. Sometime later Cheyne became preoccupied with his own whaling interests at Cape Riche (Stephens 1961, 1963). This allowed Captain Thomas Symes to replace Cheyne as the principal trader and supplier to the whalers at the bay in the 1840s and 1850s.

In those days, the track to Albany and Two Peoples Bay was ill-defined and the following comments from Ms Mary Taylor, who lived in the district in the 1830s, tells of the arrival at Candyup of

…Mr Cheyne, Mr Morley, Mr Drake and the Doctor of a French whaler. They were all dreadfully tired and famished with hunger, having been lost in the bush since daylight, coming from Two Peoples Bay, a distance of fourteen miles. (Mary Taylor)

Whaling activities at the bay peaked in the early 1840s, after which they steadily declined. The foreign whalers were gradually replaced by small parties of settlers who used whaling as a means of supplementing their incomes, much the same as they had done with sealing (Hicks 1966). Similar to the sealing industry, bay whaling was gradually reduced to insignificance through the depletion of whale numbers.

During its heyday, Two Peoples Bay was an anchorage particularly preferred by foreign whalers, not only for whaling, but also for a number of other benefits. Firstly, the bay was a safe anchorage, particularly from westerly winds. However, a south-east wind was a different matter. On 28 August 1842, a south-east gale buffeted several whalers in the bay. One, the Avis, parted her cable chains and was blown ashore and wrecked, the hulk being two-thirds buried in sand (Henderson 1980). As was the normal practice, the hulk and all salvageable items including 800 barrels of oil on board were sold.

Secondly, there were no harbour dues or import duties to be paid for items landed at Two Peoples Bay. Albany merchants George Cheyne and Thomas Symes provided the facilities in Albany to allow distribution of such goods as were traded. Trade was particularly good in whale bone and whale oil, two commodities easily disposed of in the small colony. Government officials became concerned about this smuggling and trading, yet were helpless to counter it, as the distance and access from Two Peoples Bay to Albany was sufficiently difficult to make it impossible to police the situation (Heppingstone 1969).

Thirdly, by staying at Two Peoples Bay, away from King George Sound, the masters of whalers were able to control their crews. Drunkenness in port was a major concern to both the captains and local officials since the crews usually became a public nuisance. By anchoring out of port, the crew could be given leave to the settlement in small numbers, yet be close enough to be recalled easily. The bay had the added advantage of being within easy reach of supplies and medical assistance, should the captains need these.

Fourthly, the bay provided plentiful supplies of water and fresh meat. Water was easily obtained from a stream at the north end of the bay, and fresh meat could be obtained from a number of sources. Mutton-birders and out-of-work sealers hunted kangaroos (Macropus spp.) and mutton birds (Ardenna tenuirostris) to sell to the whalers (Heppingstone 1966). The whalers also hunted kangaroos with dogs as the Indigenous Australians had done before them. In November 1841, Archdeacon Wollaston noted in his Picton Journal that he purchased four kangaroo-dogs from the captain of an American whaler, Francis Coffin, master of the Samuel Wright (Wollaston 1948). Obtaining water was a crucial part of the lives of the whalers. N. C. Haley, a young harpooner who first came to Two Peoples Bay on board the Charles W. Morgan in 1849, described the procedure in detail as the ship took on 100 barrels of water (Haley 1951).

In addition to the avoidance of import duties, as described above, there were also other problems for local officials at Albany. Of particular concern was the ease with which felons and deserters could escape justice by gaining passage on whaling ships stationed in the bay. A documented example of such a case exists. George Dutton, who had been committed to the Albany prison on a charge of robbery, escaped from the cell ‘by cutting away a portion of the cell door’. Peter Belchers, the Acting Resident Magistrate, continued:

he had gone to Two Peoples Bay where I forwarded with a party of soldiers in the hope of being able to secure him, but I found that he had managed to get on board an American Whaler which sailed from the Bay a few hours before my arrival. (Peter Belchers)

Relations with the Indigenous Australians had improved since Lockyer’s account of contacts between sealers and Indigenous Australians in 1826. Haley (1951) reported that the Indigenous Australians continued to come to the bay despite the presence of the whalers:

The wandering bands of natives from inland used to come here in the whaling days and feast on the carcass of any whale that had drifted on shore and would gorge themselves on it even if it smelt a mile a minute. (Haley)

This opportunism of Indigenous Australians was common around the bays of the south coast where whaling occurred (Heppingstone 1969). Indigenous Australians were also employed on occasions as messengers by the whalers. The captain of the Charles W. Morgan had on a previous visit to Two Peoples Bay, ‘sent a message to one of the leading men in a town sixty miles away’ (it was only 20 miles not 60) by an indigenous messenger, with the promise of a bucket of ship’s biscuits as payment. Only thirty hours later a reply had been returned to Two Peoples Bay. The story continued that whereupon the messenger was paid, he sat down by a stream of fresh water, ate all the biscuits, took a long drink, and then hardly moved for two days.

Indigenous Australians were later employed as crew in the settlers’ bay-whaling enterprises and were considered to be equal to their fellow white crew members (Heppingstone 1969). If a report from the Inquirer in 1858 is correct, the employment of Indigenous Australians as whalers caused something of an upset in Aboriginal society: ‘The black ladies now declare they will accept no husbands except if they will go fishing (whaling).’

Local settlers continued bay whaling at Two Peoples Bay. The foreign whalers had turned their attention to hunting the sperm whale (Physeter microcephalus), which did not frequent the bays of the coast, as did the southern right (Eubalaena australis) and humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) whales they had hunted previously. Bay whaling progressively became the domain of small groups of local people, who were not able to make the enormous profits of the past, because the number of whales had been reduced.

Landward development

Beverley–Albany railway

By the mid-1880s, Albany’s development was essential to the surrounding countryside and therefore the construction of the Beverley–Albany section of the Great Southern Railway became crucial to the development of the entire district. In the colony at that time capital was limited and became the major problem delaying constructing the much sought-after railway.

A method in vogue at the time was to attract overseas capital by means of the Government offering large tracts of land in return for a company constructing a railway line. Land thus procured could then be leased or sold as the company saw fit. The land grant contract signed by the Western Australian Government and W. A. Land Company, committed the Government:

to grant 12,000 acres [4800 ha] of land per mile [1.6 km] of railway, which were selected in blocks not less than 12,000 acres in size, and within a belt 40 miles [64 km] either side of the line. (Garden 1977)

Another clause granted the company an extra ‘50 acres [20 ha], to be selected in blocks no smaller than 5000 acres [2000 ha]’ for each migrant brought to the Colony by the company (Garden 1977).

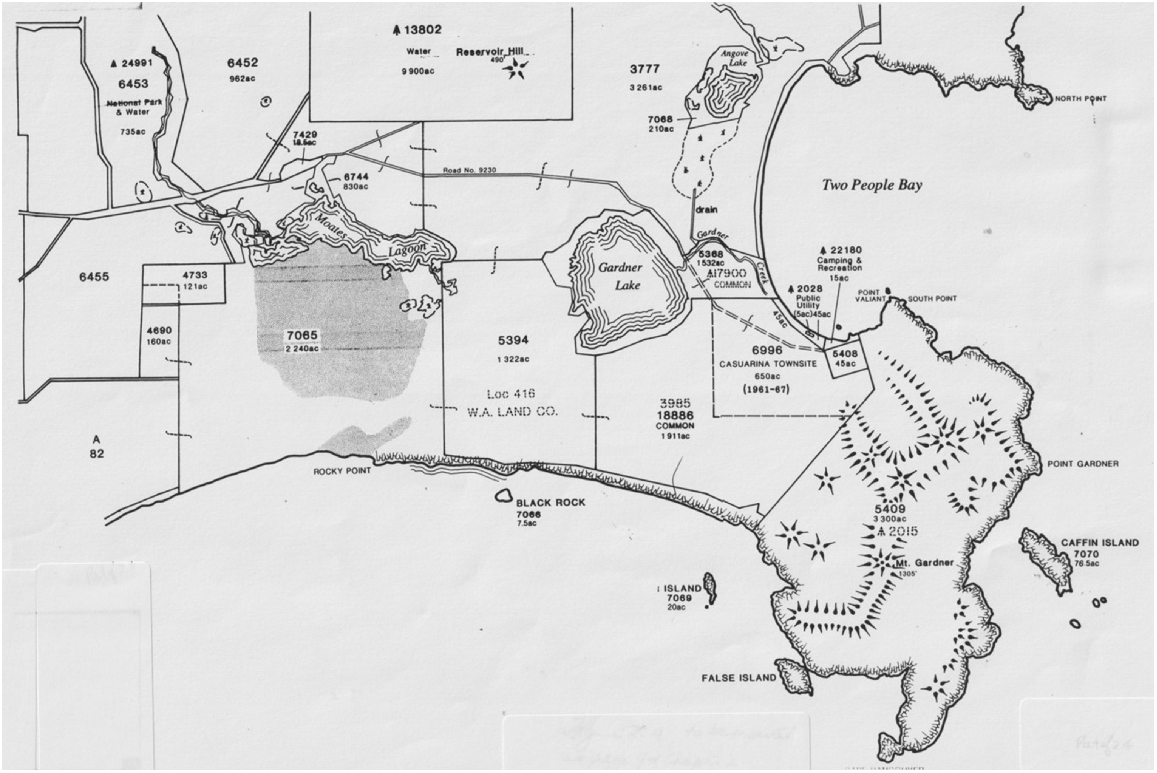

After many delays, the Beverley–Albany line was completed in 1889, and the W. A. Land Company then set about applying for land grants under the terms of the contract. Location 416, situated east of Kalgan River, which took in almost all of the present Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, was one of the selections made by the Land Company.

The reserves

When Two Peoples Bay location 416 was granted to the W. A. Land Company, on 12 May 1892, it did not include the whole area applied for. Two existing reserves, Nos 2015 and 2028, were excluded from the grant. The Company did not agree to the exclusion of these two reserves and carried on a lengthy and sometimes heated debate with the Government, in its attempts to obtain these areas.

Reserve No. 2015 (approximately 1320 ha) (Fig. 3) was set aside for defence purposes in March 1892, after the area was withdrawn from the sale lists in May 1890, on the instructions of the Secretary of State. The defence of Princess Royal Harbour had been discussed by the British and Western Australian Governments in early 1890. Through instructions cabled to the Department of Lands and Surveys in April and May 1890, the Secretary of State ordered that all land that provided vantage points to King George Sound and Princess Royal Harbour be withdrawn from the lists of Crown land available for sale. This action would allow the development of these vantage points as defence centres and maximise the defence of the Sound and its harbour. Mt Gardner was one of the areas withdrawn from the Crown land lists. However, the pressures that led to its withdrawal from land lists were not great enough to have the area designated a reserve.

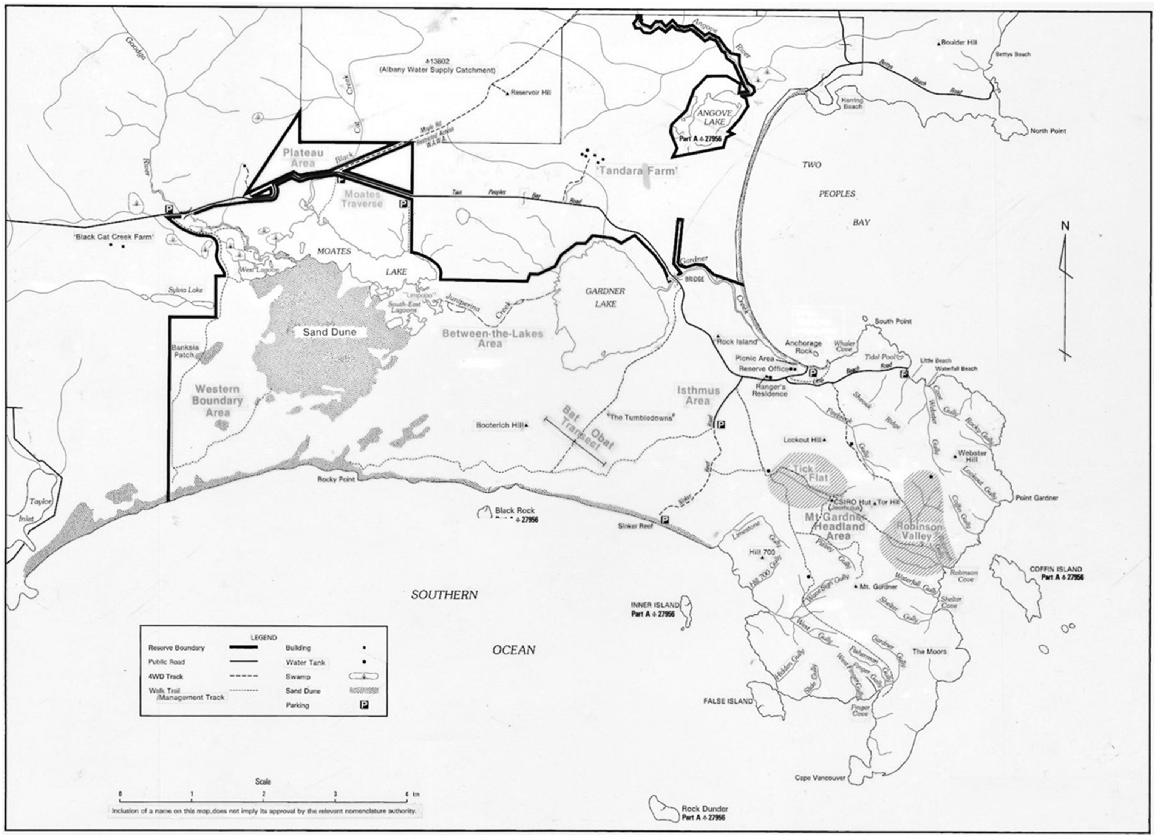

Map of Two Peoples Bay area showing the original land title boundaries and nomenclature and locations allocated to the W. A Land Company. Drafted from lithographs held by the Department of Land Administration.

By March 1892, the influence of the Great Southern Railway and the application for the Mt Gardner area by the W. A. Land Company provided the impetus for the WA Government to reassess the reserve status of the area. It was considered that the added strategic importance of the harbour and the railway line required the establishment of gun emplacements on Mt Gardner, for the harbour’s defence. Mt Gardner was therefore reserved and not made available for private use. To complement the defence reserve, the State Government set aside a 5 acre (2 ha) reserve, No. 2028, as a landing place, though it was officially gazetted Public Utility.

In its attempts to obtain the two reserves, the W. A. Land Company argued that Reserve 2015 was excessive in size and that, as there had been no further discussion on the establishment of defence works on the site, the reserve should be cancelled. The construction of Fort Scratchley on Mt Adelaide during 1891-2 resolved the question of defending Princess Royal Harbour and for a while discussions ceased on the issue. Upon cancellation of the reserve, the area should be added to Location 416 and the Government could have the right to ‘resume any portions of the land to set up reserves for defence purposes within 21 years’ of Location 416 being granted. It was also argued that by retaining Reserve No. 2028 the Government would ‘prevent the sale of land in small lots for settlement around the landing place.’ The W. A. Land Company continued that ‘there should be a settlement or village at that place’ and that having a government reserve there would inhibit the development of such a townsite. Just how prophetic these words proved to be, can be judged when the issue of Casuarina townsite is discussed later. The W. A. Land Company’s representations were not successful, and the two reserves remained excluded from Location 416.

Owning land and encouraging its development proved to be two distinct functions for the W. A. Land Company. Those areas of land controlled by the Company developed slowly. The infertile nature of much of the land and the heavy forest covering vast areas were factors retarding the sale of the land. On Location 416, the land around Two Peoples Bay suffered from soil problems and subsequently was not seen as a profitable investment. Other factors such as high prices for sale and lease of Company land retarded the growth of the Albany district. Eventually, the State Government bailed out the investors who had backed the W. A. Land Company, by purchasing all unsold lands and the Great Southern Railway for one million pounds. Land sale prices and leases were reduced to Government rates and an increase in the sale of land was noted. However, the land that now makes Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was not purchased, though several long-term leases were taken out for various parts of the area.

According to records, N. W. Mckail became the first person to lease land in the general area when he leased Location 3985 from the Company in 1893. Location 3985 is the area east of Gardner Lake and to the western boundary of Reserve 2015. A second lease in early 1900s, for an area of land between McKail’s block and the eastern end of Moates Lake, was granted to A. de Baun. Later, in 1925, A. and O. Thorne were given a lease for Location 5394; the land between Moates and Gardner Lakes, including part of de Baun’s earlier lease. The more northerly section of de Baun’s early lease was reserved as Common Reserve No. 17900 on 13 January 1922, but not vested in any authority. Location A82 was surveyed and released in 1898. It forms part of the western boundary of the current Nature Reserve. Location 3777 was released in 1911 and forms part of the northern boundary.

During these early years of tenure, the Reserve area was reputedly used for cattle grazing and a number of people believe the mobile dunes near Moates Lake were part of a sand blow-out caused by the overgrazing of livestock. However, descriptions relating to the coastal survey map of 1877 note ‘a bare sand drift one mile square’ (1.6 × 1.6 km). This suggests these dunes preceded grazing activities.

Albany water supply

In the first decade of the 20th century Albany suffered from a poor water supply and good freshwater was needed for shipping purposes. A solution was proposed by surveyor W. H. Angove while surveying Location 3777 (Tandara Fig. 4) in 1911, when he relocated a stream in the hills (now Angove River) he had first recorded in 1898. Mr Angove, who was also an Albany Town Councillor, succeeded in convincing his fellow councillors that this stream could provide the water so desperately needed in Albany. An area of 20,000 ha was set aside as a catchment reserve and following governmental approval in 1912 work commenced on the Angove weir and pumping station.

An upstream weir across a clear pool was constructed to supply water through a 25 cm wooden pipeline, 2.5 km to the pumping station, where a second weir was constructed across the stream. Two small Babcock and Wilcox water tube, wood-fired boilers were installed to generate steam for the pumps to convey water through another 25 cm wooden pipeline to the summit tank on Reservoir Hill. From there the water was gravity fed, via a 20 cm cast iron and wood pipeline, to a reservoir on top of Mt Clarence, near Albany.

The water supply scheme was upgraded from steam to electric power in 1953 with the conversion of the power supply and the installation of the present pumphouse and steel pipelines, which run alongside the main road leading to and through the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Also, in 1953, the Water Supply Catchment Reserve No. 13802 was reduced to 4006 ha. Angove River is still providing a major part of Albany’s water supply.

An interesting adjunct to the town water supply scheme was an unfilled proposal to establish a trout hatchery below the weir. Toward this end the Fisheries Department of the time had water temperatures monitored daily, and the information was relayed to Perth at regular intervals throughout 1916 and 1917. Temperature sheets were dutifully maintained by J. A. McCallum, engine driver at the pumping station, under the supervision of A. M. Hutchinson, engineer to the Albany Water Board.

Early recreational pursuits

The settling of areas in the immediate vicinity of the bay, in the early 1900s, led Albany people to use Two Peoples Bay for picnics and relaxation. Access, usually by horse and cart, was along a sandy track via the pumping station to the northern end of the bay, and then followed the shore south. This was a different route to the track from Taylor’s Inlet via Gardner Lake to the southern end of the bay, as shown on maps issued in 1890.

When World War I commenced, picnic parties to Two Peoples Bay ceased. Only the pumping station master and his assistant remained at the pumping station to ensure Albany’s water supply. However, there was renewed activity at the bay when the war ended in 1918. Location 3777, known today as Tandara, was settled permanently by H. C. Poole and work commenced to make the farm a viable proposition. His son John Poole and two young friends dug the first drains by hand, from Angove Lake to a stream course leading into Gardner Creek, completing the onerous task by 1930. This allowed the fertile swamp flats to be used for potato cropping (Mr and Mrs West, pers. comm.).

For a number of years, two fishers spent approximately 6 months of the year living on their boat, or on the shore in the general vicinity of Reserve No. 2028. The fish they caught were smoke-cured in a kiln of sorts, in the same gully area where the bay whalers had previously rendered the oil from whales they had taken in the bay (Mr and Mrs West, pers. comm.).

Development proposals

Following the end of World War II, Two Peoples Bay remained popular with Albany residents and was visited by increasing numbers of tourists who enjoyed the wide variety of recreational pursuits. The duration of the visits began to lengthen and the picnic shelters of the early 1930s developed into substantial buildings of a permanent nature. By 1953, there were about 17 buildings in the squatter settlement at Two Peoples Bay. The addresses of shack owners reflected the increase in the number of non-Albany visitors to the bay. Farmers from neighbouring districts came to spend their time relaxing over the summer break. Though Albany residents continued to visit the bay over weekend periods, the major influx of people came during the summer holidays. The area was seen as ideal. It was isolated from local authorities and there was plenty to do: fishing, swimming, horse riding, and even boating. Perhaps the greatest attribute was that it was free.

Even before World War II an application was received by the Department of Lands and Surveys for the purchase of 6 ha at South Point. The area north-east of the existing squatter settlement was proposed for development as a tourist resort. Activities such as horse riding, boating, swimming, and golf were to be available to the tourists. Although the application for the tourist resort was dropped, negotiations between the Department of Lands and Surveys and the Albany Road Board resulted in the establishment of a 15 acre (6 ha) reserve for Camping and Recreation (Reserve No. 22180). This area was set aside in April 1940 and vested in the Albany Road Board so the Board could control the increasing numbers of squatters using the bay area. It was also agreed that the Road Board would not have power to lease any of the area as camping sites. To strengthen the Board’s control of the area, Location 3985 was set aside as a Common Reserve (No. 18886), vested in the Road Board. A lease on this location was taken out in 1925, but was abandoned some time prior to April 1940.

Increased interest in the bay as a holiday resort was seen in the large number of applications received by the Department of Lands and Surveys and the Albany Road Board for leases of areas of land, ranging from half an acre to two acres (0.2–0.8 ha), as building sites. By 1953, public pressure for building sites at Two Peoples Bay strengthened the resolve of the Albany Road Board to provide for more effective control of the squatter settlement. Subsequently the Board applied to the Under Secretary of Lands to have Public Utility Reserve No. 2028, which had been increased to 45 acres (18 ha) in January 1922, added to its Camping and Recreation Reserve No. 22180. It was argued that, if this amalgamation of Reserves was permitted, the squatter settlement could be controlled under existing Government by-laws. Furthermore, the Albany Road Board argued, it was desirous to have power to lease parts of the area to people for periods of up to 21 years as camping and caravanning sites.

As a result of this Albany Road Board application and the increase in private applications for sites at Two Peoples Bay, the Department of Lands and Surveys began considering the declaration of a townsite at the bay. A survey carried out by a Government surveyor in 1954 reported an air of permanence about the squatters’ settlement. Vegetable gardens had been established in some of the swamp areas and the houses themselves were becoming more sophisticated. One house had a power plant valued at £600 in a separate shed.

The idea of building a tourist resort was also revived in 1954, and again in 1957, when separate applications were made to the Under Secretary for Lands to allow Public Utility Reserve No. 2028 to be opened for a camping area and a hostel, respectively. The 1957 application to build a hostel was detailed and supported by the Albany Tourist Bureau and Mr J. Hall, Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Albany. It was planned to develop golfing and tennis facilities, and to allow horse riding. Pasture was to be grown on the Common Reserve and the hostel was to be self-sufficient in vegetables as the swamps were to be cleared and used to grow vegetables. This was the most complete application, for the development of tourist facilities, received by the Under Secretary for Lands. By this time, the idea of establishing a townsite had matured sufficiently, and the reply to the developers made it clear that the development of such facilities would be considered, as part of an overall concept of a townsite designed for the area.

Casuarina townsite

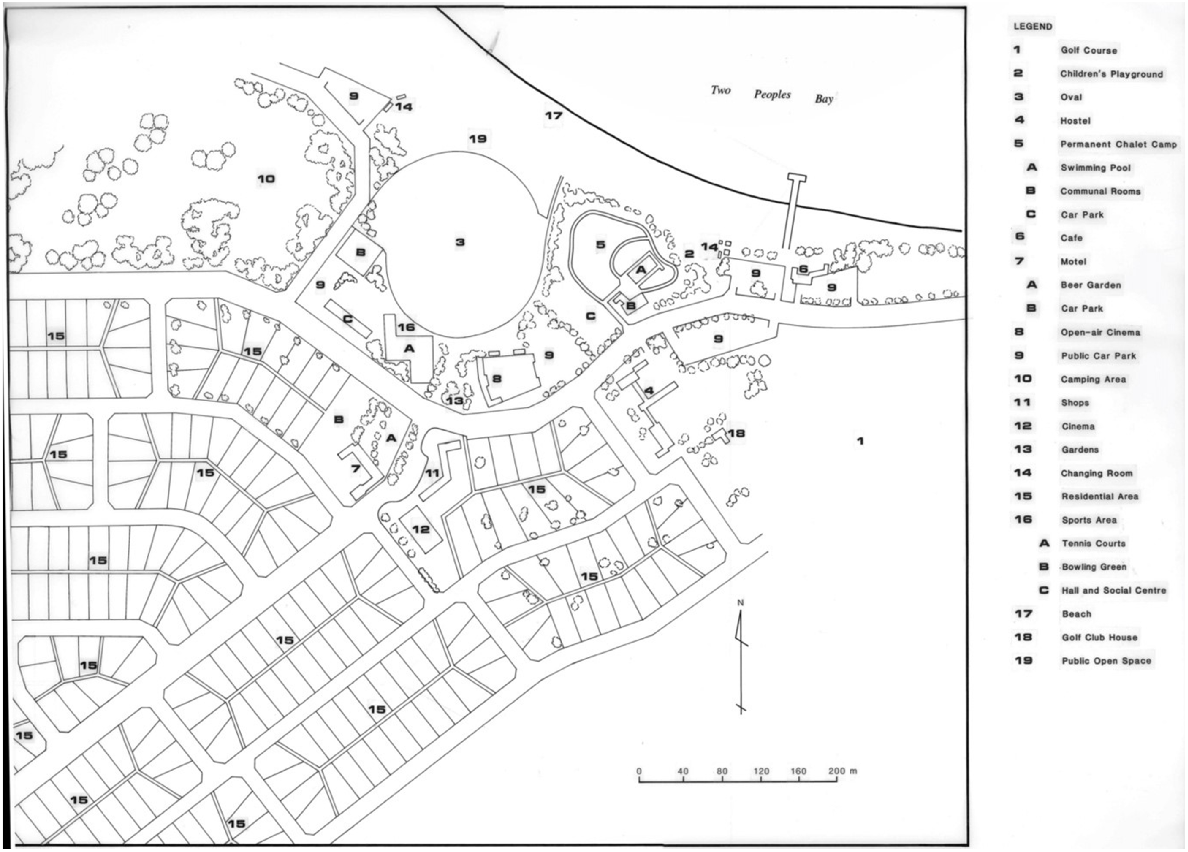

From the point of view of those desiring building lots, the story of the survey, declaration and opening for sale of what became known as Casuarina townsite, is one of frustration and bad timing. Following completion of the initial survey in December 1954, the townsite design of 50 half acre (0.2 ha) lots was rejected by the Town Planning Department. Having had its first townsite design rejected, the Department of Lands and Surveys sought the assistance of the Town Planning Department to redesign the townsite. A Town Planning representative was sent to the proposed townsite in November 1955, however, the completed design was not submitted to Lands and Surveys until February 1957 (Fig. 5).

Proposed layout of the Casuarina townsite at Two Peoples Bay, cancelled with the gazetting of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1966. Adapted from the original plan held by the Department of Land Administration.

By July 1957, the three authorities concerned with the declaration of the townsite had reached agreement. At this point, administrative procedures involved the checking of the surveyor’s calculations and drawings, and results of those checks delayed any further action until November 1959. The surveyor’s calculations were found to have errors that required the survey be redone. By May 1960, the resurvey was completed, the calculations checked, and found to be correct.

The procedure for declaring a townsite required that the townsite be named. The Nomenclature Advisory Committee was asked to propose a name for the townsite and to name the streets. The name chosen by the Committee was Casuarina (after Louis Freycinet’s ship) and the street names were those of members of the French 1800–1804 expedition and the American ship the Union. Casuarina townsite was formally gazetted on 30 March 1961, 8 years and 5 months after the initial proposal to establish a townsite at Two Peoples Bay (Fig. 5). In the intervening period, between the declared intention to establish a townsite and its gazettal, interest in the area as a holiday site continued to grow. Every inquiry about obtaining land at Two Peoples Bay was replied to in a like manner; progress was being made and as soon as the area was declared a townsite, the inquirer would be informed of the conditions of purchase, sale dates, and places.

Now the townsite was gazetted it would appear that the time of frustration was over. The Under Secretary for Lands directed that public notices, advertising an auction of 15 lots at Casuarina townsite, be prepared and displayed at all railway stations between Perth and Albany on the Great Southern Railway line. The auction was to be held at the Albany Court House on 22 June 1961 at 2.30 p.m. Minimum prices on the 15 lots to be auctioned were set. On the 18 April 1961, only 5 days after the instruction to prepare for the auction of the lots at Casuarina, the following note appeared on file from the Divisional Surveyor for Great Southern:

Following the altered policy of this and the Town Planning Department re sanitary provision (septic tanks) in the matter of necessary water supply, it has been decided to re-subdivide the ‘Casuarina” area to provide (about) quarter acre lots. This will necessitate the survey of the broken lines as shown. (Department of Land Administration 7932/54, Vol. 1, p. 149)

This note proved to be a crucial turning point in the destiny of the Casuarina townsite. Instructions were issued for the immediate resurvey of the blocks. However, for some reason the survey was not completed until March 1962, by which time another issue had arisen, which created a new focus in the debate on land use of the bay area.

The confirmation of the existence of the noisy scrub-bird at Two Peoples Bay, in December 1961, changed the course of development of the area. Had the policy on sanitary provisions of the Department of Lands and Surveys and the Town Planning Department not changed until after 22 June 1961, there could now be a town called Casuarina instead of one of Western Australia’s most important and valuable nature reserves.

Further recreational developments occurred during the period 1953–61, when fishing was still a dominant pastime. Several dedicated trout anglers introduced trout into the Goodga River (H. White, pers. comm.), to supplement the marron (Cherax spp.) that had been introduced in the late 1930s. Spear fishing had also become prominent at the bay.

Also, professional fishers, particular salmon fishers, again established themselves at the bay on a fairly permanent basis. From 1954 onwards, Mr C. Wilson lived at Two Peoples Bay and worked as a professional fisher. His persistence in seeking land as a base for his undertaking resulted in a small area being excised from the Nature Reserve after its establishment. The Wilson family set up a stall near the beach at weekends where fresh salmon and Devonshire Teas were sold to picnickers and other visitors to the bay (R. E. S. Sokolowski, pers. comm.).

Establishment of the nature reserve

The western bristlebird

As access to Two Peoples Bay became easier, the number of people using the area increased, with fishing remaining the dominant recreational activity. A growing number of the people who came to fish were also naturalists, who were able to pursue their hobby in the rich diversity of plant and animal species of the area. One such person, Mr C. Allen, had begun a long association with the bay area in the late 1920s. On his numerous visits he became acquainted with birds that were not readily identifiable and he suspected one bird with a particularly piercing call was the noisy scrub-bird (C. Allen, pers. comm.).

In February 1945, Mr. K. Buller, of the Western Australian Museum, went with Allen to Two Peoples Bay ‘with hopes of seeing or hearing something of interest’ (Buller 1945). Indeed, they did find something of interest, as it was during this excursion that the first sighting of a western bristlebird (Dasyornis longirostris) was made since the last specimen was collected in 1907 (by F. B. L. Whitlock, near Wilson’s Inlet). The two men moved from the area around Gardner Lake, where the western bristlebird had been sighted, to the southern end of the bay and heard calls of this bird ‘within a stones (sic) throw of an inhabited fisherman’s camp’ (Buller 1945). It is interesting to note that years later, in this same area only a short distance from the squatter’s settlement, the noisy scrub-bird was found. The two ornithologists were pleased with their discovery and in their discussion about the day’s events, some doubt was raised as to whether or not the bird originally seen by Allen was the noisy scrub-bird, or the now confirmed western bristlebird.

In many ways, 1961 was a pivotal year in the course of events at Two Peoples Bay. During that year, two parties of ornithologists independently undertook studies of the western bristlebird. A group comprising Messrs. J. R. Ford, K. G. Buller, and C. Allen began a taxonomic study while, unknown to them, Mr H. O. Webster began a study on its breeding and behaviour (H. O. Webster, pers. comm.). The group Ford, Buller, and Allen were working on the western bristlebird with the knowledge of the Western Australian Museum and wrote, in a report on the progress of their work:

For some time now, we have been hopeful of rediscovering the Noisy Scrub-bird in the Two Peoples Bay district… One of us (Allen) is positive that he saw and heard the species in 1944 but the fact remains that we have been unable to verify our contention by collecting a specimen. (Department of Conservation and Land Management File No. 015163F3807 – Rare and Endangered Fauna: Noisy Scrub Bird, Vol. 1, p. 32)

Noisy scrub-bird rediscovered

Among ornithologists, the hope of positively identifying the noisy scrub-bird never really faded. Occasional reports of sightings were given to the Department of Fisheries and Fauna, but mostly these were shown to be incorrect or unsubstantiated. The last of these reports was received from Nannup in August 1961.

Hopes of positively confirming Allen’s 1944 sighting were given an added boost when Mr P. Fuller returned from a trip to Albany and told Ford that, on 5 November 1961, he and Allen had been at Two Peoples Bay and had again sighted a bird that Allen was certain was the noisy scrub-bird (Ford 1963). Ford made plans to visit Albany in the company of Buller, the trip being carried out over the weekend 11–12 November 1961. However, Allen did not accompany them to the bay and in Ford’s words they ‘inadvertently worked the margins of Lake Gardner about one mile from the actual place where the scrub-bird had been watched by Allen and Fuller, and consequently missed confirming Allen’s record.’

Although Ford and Buller did not confirm Allen’s sighting, their trip to Two Peoples Bay was not fruitless. Four specimens of the western bristlebird were collected to continue their study. Also, it was enlightening because, when Ford and Buller visited Allen on the Sunday evening and showed him the western bristlebird skins, Allen categorically stated that these were different from the bird he had seen. Allen then pointed out the differences between the specimens and the bird he had seen (Ford, Buller, and Allen, pers. comm.). Ford and Buller returned to Perth anxious to coordinate their free time, for another trip to search the area near the squatter’s settlement, as it was in that area Allen and Fuller had made their observations on 5 November.

Two of the western bristlebirds collected on that trip were a breeding pair being studied by Webster. It was through this most regrettable situation that the two parties of researchers came in contact. Webster found evidence at the site, where he had been observing the western bristlebirds, indicating they had been collected by a person or persons associated with the Museum. Enquiries led him to believe that Ford had collected the birds, though he made no approach to Ford as he was unknown to Webster at that time (Webster, pers. comm.). As can be imagined, Webster was very annoyed at having his research so abruptly ended.

Dr W. D. L. Ride, then Director of the Museum, became aware of the situation and, through Dr D. L. Serventy, communicated to Ford early in the week 23–30 November, that he should contact Webster to explain the situation surrounding the taking of the two birds. Ford followed up the suggestion by telephoning Webster. During the conversation he passed on information about his group’s work on the western bristlebird and mentioned in passing their hope of finding the noisy scrub-bird in the Two Peoples Bay area. Ford followed up the telephone conversation by writing a brief note to Webster on 30 November 1961. In it he explained something of the group’s work on the western bristlebird and then wrote:

I also mentioned the Scrub-Bird in my phone call. As far as I’m concerned, this bird is not extinct but undoubtedly has disappeared from many of its haunts due to alteration of its habitat, The Two People [sic] Bay area appears to be the type of country in which Webb, Masters and Gilbert found the Scrub-Bird, but as yet I have heard no strange calls nor seen any bird that may have been this species. However I have been informed by a naturalist friend of mine that in 1944 he saw heard a Scrub-Bird, so this is a promising clue. Perhaps if you saw any strange bird you could let me know?’ (Ford in litt.)

Webster had not been to the bay since discovering that the pair of western bristlebirds he had been observing had been collected as specimens. On 17 December, he again went to the area, this time to fish for black bream (Acanthopagrus butcheri) in the stream that flows from Lake Gardner to the sea. He described in his field notebook how a series of fairly long and very loud, frequent calls distracted him from fishing and drew him away to a rush-covered swamp area to try and identify the mystery caller. He spent the remainder of the day following the bird through very thick swamp and scrub and: ‘came away in the evening with impressions of a brown bird with a call that really made my ears ring and with the knowledge that it was almost certainly the Noisy Scrub-bird’ (Webster 1962a).

A more positive identification was possible the following weekend after good sightings were made of the distinctive: ‘…yellow gape, the inverted white ‘V’ under the beak and the blackish triangular patch below it… the wings were rounded, did not reach to the base of the tail and had darker brown fine barring running across them’ (Webster 1962b).

Webster had his news published in the West Australian newspaper on 25 December 1961; a Christmas present to ornithologists of the world. A typical ornithological reaction to such news as the rediscovery of a species considered extinct is shown in the notes of Dr D. L. Serventy: ‘When the article appeared in the West Australian I was partly sceptical, though I respected Harley Webster as a seasoned observer.’

Serventy’s scepticism was overcome on 28 December when, in the company of Webster, and later Ford and Allen, he satisfied himself by gaining good views of the bird; that it was in fact the noisy scrub-bird. Allen also confirmed that it was the same species he had seen in 1944. As all had confirmed the identity of the species, it was not considered necessary to collect a specimen to verify its identity.

The existence of the noisy scrub-bird was now no longer in doubt. The identification of the species at the same place as Allen had seen the bird in 1944 had been verified; it only remained as to who should have the honour of rediscovering the lost species. That debate continued in much the same vein as the debate between Flinders and the French over place names on the south coast.

Support from world ornithologists

Webster forecast that the effect of the rediscovery would draw the attention of ornithologists from all over the world to Two Peoples Bay. He was proved correct, even more quickly than he imagined. In January 1962, a well-known American ornithologist, Mr D. Lamm, accompanied a group to Two Peoples Bay. It was Dr G. F. Mees, a member of this group, who discovered the second noisy scrub-bird in habitat quite distinct from that of the first bird. Instead of living among the rushes in swamps, it was found in thick scrub of a valley on the watershed of Mt Gardner. This discovery led the ornithologists to explore the Mt Gardner region and they were rewarded by finding a number of noisy scrub-birds.

Two Peoples Bay became the centre of attention for ornithologists, as two rare species were now known to be in the area. The problem was to retain enough of the habitat of species in its natural state, to ensure continuance of the species. From this view point, Casuarina Townsite was considered a threat. The area of conflict centred around the Public Utility Reserve No. 2028, where townsite and scrub-bird territory overlapped.

Numerous opinions existed among ornithologists, as can be seen by the variety of suggestions put forward in the many national and international representations made to the Government of the day, to establish a reserve in the area. There were those who wanted to have the whole area of Mt Gardner and the land in the vicinity of Moates and Gardner Lakes reserved; those who considered that the townsite should be removed to the Common Reserve No. 17900 to the west of the proposed townsite and a small reserve established in the immediate area of the scrub-bird habitat; and those who wanted the townsite to stay where it was and for the reserve to be established in whatever other area was considered necessary. Between 1961 and 1967, when Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was finally gazetted at its present size and classification, all of these above options were considered. In September 1962, the then Premier, Hon. D. Brand, wrote to Webster that it was ‘proposed to create a reserve of approximately 13,600 acres [5440 ha], of which only approximately 1000 acres [400 ha] would be required for township purposes.’ This proposal was to proceed as a matter of urgency, the Reserve to be classified ‘A’ Class and vested in the Fauna Protection Advisory Committee, for the purpose of conservation of flora and fauna. The townsite, however, was to stay.

The action to proceed along those lines came to an abrupt halt when, on 28 November 1962, Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, wrote to Premier Brand noting that ‘efforts to secure the abandonment of proposed and already surveyed townsite have not been successful’ and appealed for the matter to reconsidered. The appeal for reconsideration was successful and the proposal to establish the townsite was deferred until a comprehensive investigation into all aspects of the position has been carried out. From this time on, much was made of Prince Philip’s involvement in the matter, with newspaper articles often referring to his part in the whole affair to have the townsite abandoned.

Conflict of opinions

The debate centred on the threat the proposed townsite would be to the noisy scrub-bird. Conservationists argued that the threat from fire, feral cats, and dogs, as well as increased use of the area that would open up the undergrowth, would be increased if the townsite were allowed to be developed. Other reasons for establishing the reserve were raised by international conservation bodies: ‘the enormous value, as an example to the rest of the world, of a firm decision by the Western Australian Government that no town will be built in the Scrub birds territory’

Arguing for the retention of the townsite, Hall MLA suggested that the presence of people in the area would minimise vandalism, reduce the fire risk, and retain the presence of the noisy scrub-birds, as the birds would withdraw if people were evicted from the area. A member of the squatter community also argued that the presence of people would reduce the risk of fire and vandalism, yet interestingly, then cited the problem of increased use of the area affecting the noisy scrub-bird:

Since the rediscovery of the bird has been publicised, ornithologists and curious tourists have visited the area. As a result of the birds [sic] habitat being thus disturbed, it has moved away from the immediate area. (Miss J Reeve)

In an attempt to reduce the heat of the debate, the South Coast Townsite Committee was established, one of its functions being to make recommendations on the Two Peoples Bay area. After hearing evidence for and against the retention of the townsite, the committee made its recommendations. The crucial recommendation was to relocate the townsite to the west on the Common Reserve No. 17900, if the land proved suitable. Other recommendations hinged on this first proposal. However, when surveyors and town planners viewed the proposed site, it was rejected as unsuitable, and the arguments resumed. With the failure of the compromise put forward by the South Coast Townsite Committee and the appointment of a new Under Secretary for Lands, the Department of Lands and Surveys began to favour the representations made by Hall, the Albany Shire, and individuals desiring retention of Casuarina townsite.

Conservation groups became increasingly alarmed and the number of representations, in particular from international bodies, began to increase. One international body, the World Wildlife Fund, gained prominence in reporting of the debate, as it was known that the Duke of Edinburgh was involved with that group. By March 1965, the balance had swung in favour of the hard-line conservation groups, as shown in a file note on a Lands and Surveys file:

If the desire is to create a Reserve for the ‘Protection of Fauna’ and vest the area in the FPAC (Fauna Protection Advisory Committee) to exercise overall control, then no action should be taken to establish a townsite. In fact the existing ‘squatters’ should be removed and development to take place on freehold land some distance away. (Department of Land Administration 995/62, Vol. 1, p. 126)

Establishing the nature reserve

Meetings between the Departments of Fisheries and Fauna and Lands and Surveys were held during October 1965. In these, it was agreed that the Casuarina townsite should be cancelled and a reserve created for the conservation of flora and fauna, vested in the Fauna Protection Advisory Committee. The Committee alone should be responsible for resolving the squatter problem. By February 1966, the Shire of Albany had agreed to relinquish control of all its vested reserves in the bay area. The way was now clear to establish Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve formally. The formalities were completed when, on 22 April 1966, a notice in the Government Gazette proclaimed the establishment of Reserve No. 27956.

News of the event spread rapidly, and letters of congratulations came in, to the Premier and various Ministers, from many conservation groups around the world who had made representations for the establishment of the reserve. Unfortunately, the original gazettal notice had not been correct. Only two locations were included in the reserve; Location 5408 (Reserve No. 2028) and Location 6906 (Casuarina townsite). The area thus reserved was reduced compared with the area committed by various Ministers at earlier times. The error was discovered, the original gazettal notice cancelled, and a new notice published on 28 April 1967, along with the vesting of the reserve in the Fauna Protection Advisory Committee. On 2 June 1967, the reserve was classified as a class ‘A’ reserve. Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve had been established and could not be altered except by Act of Parliament. The problems of managing such an expanse of land with its numerous rare species of flora and fauna, as well as the fragile environment and the squatter problem, were now the responsibility of the Fauna Protection Advisory Committee.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was established by the Western Australian Government, by a deliberate decision to support conservation, as a result of much debate and discussion involving conservation groups, government departments, individuals, and parts of the international conservation community. However, the history of the area shows that such decisions were not solely responsible for the existence of this Reserve. Although matters of remoteness and poor agricultural soil were influential, a conservative approach to decisions and matters of policy is an essential part of the history of the area, ensuring that much of it remained in a natural state. It is hoped this history, up to the time Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was created, will not only provide interesting reading, but will also describe the setting for the future management of the area.

Acknowledgements

G. R. Chatfield was the original author of this paper, which was written for a special bulletin of CALMScience on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The paper was subject to peer review, revised, and accepted for publication in 1991. The special bulletin was never published. In resurrecting the papers collected for the special bulletin, in order to publish them over 30 years later in the special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology, no record of G. R. Chatfield’s status or whereabouts could be found. Accordingly, DAS updated Chatfield’s paper and edited it for publication. The paper is essentially that which Chatfield presented for publication, with minor changes in response to the reports from two reviewers, and to incorporate the extensive footnotes into the text and reference list, to conform to the format required by Pacific Conservation Biology. G. R. Chatfield’s acknowledgements: compiling this history required substantial amounts of time researching written documents and talking with long-term residents of the immediate area, local historians, and those involved in the rediscovery of the noisy scrub-bird. My deepest thanks to: Mr and Mrs D. A. P. West for their invaluable assistance in charting the course of developments from 1911; Mr G. L. Johnson, local journalist and history enthusiast of the area, who provided a number of useful leads into the maritime history of the area; Mr H. White, President of the Western Australian Historical Society, Albany Branch, who gave freely of his time and knowledge, as did the staff of the Albany Shire Library. Other long-term Albany residents, Messrs W. W. Green, P. Evans, and F. North, supplied interesting information and photographic records of activities at Two Peoples Bay. Ms K. Hendersen of Battye Library, Perth, patiently dealt with my numerous enquiries and requests in a most helpful and cheerful manner as did the staff of the Western Australian Maritime Museum and the Head Librarian, Reid Library, University of Western Australia. Professor L Marchant, University of Western Australia, provided helpful suggestions concerning the French expedition of 1800–1804. The former Surveyor General of the then Department of Land Administration permitted research of Departmental files and archival material, and provided facilities to work while in the archive and records section. The section on the rediscovery of the noisy scrub-bird is controversial. To come to my conclusions, detailed individual interviews were held with each of the persons involved. The information from these interviews was complemented by examining documentary evidence, both published and private correspondence, which the individuals supplied. I am grateful to the late Dr D. L. Serventy (1904–1988), the late J. R. Ford (1932–1987), and Messrs C. Allen. K. G. Buller, P. J. Fuller, and the late H. O. Webster (1909–1990), for without their assistance this section would be incomplete. Denis A Saunders’ acknowledgements: I am grateful to Emeritus Professor Don Bradshaw and Emeritus Professor Harry Recher AM, who provided critical reviews of the penultimate draft of this paper, and Emeritus Professor Mike Calver, editor-in-chief Pacific Conservation Biology for his encouragement and editorial support.

References

Buller KG (1945) A new record of the Western bristle-bird. Emu 45, 78-80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ford JR (1963) Western Australian Branch Secretary Notes. Emu 63, 185-200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Glover R (1953) Captain Symes at Albany. Journal and Proceedings of the Western Australian Historical Society 6, 74-93.

| Google Scholar |

Henn PU (1934) French Exploration on the Western Australian Coast. Journal and Proceedings of the Western Australian Historical Society 2, 1-22.

| Google Scholar |

Heppingstone ID (1966) Bay whaling in Western Australia. Journal and Proceedings of the Western Australian Historical Society 6, 29-41.

| Google Scholar |

Stephens R (1961) History of Two Peoples Bay. Albany Advertiser 27 June 1961.

| Google Scholar |

Stephens R (1963) Two Peoples Bay Once Had a Sealing Industry. The Countryman Perth 23 May 1963.

| Google Scholar |

Vancouver G (1967) ‘A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World’. Bibliotheca Australiana No. 30 Da Capo Press New York.

| Google Scholar |

Webster HO (1962a) Rediscovery of the Noisy Scrub-Bird, Atrichornis clamosus. Western Australian Naturalist 8, 57-59.

| Google Scholar |

Webster HO (1962b) Rediscovery of the Noisy Scrub-Bird, Atrichornis clamosus – Further Observations. Western Australian Naturalist 8, 81-84.

| Google Scholar |

Wollaston JR (1948) Wollaston’s Picton Journal 1841–1844: being Volume 1 of the Journals and Diaries (1841–1856) of Revd. John Ramsden Wollaston, M.A., Archdeacon of Western Australia, 1849–1856. Collected by Rev. Canon A. Burton - Perth: C.H. Pitman, 1948; reissued University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1975).