Time of seed harvest and sowing determines successful establishment of kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) on Dja Dja Wurrung Country

Dylan Male A * , James Hunt

A * , James Hunt  A , Corinne Celestina

A , Corinne Celestina  A , Dorin Gupta

A , Dorin Gupta  B , Gary Clark

B , Gary Clark  C , Rodney Carter D and Dan Duggan D

C , Rodney Carter D and Dan Duggan D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra Forssk.) is a native perennial C4 species significant to Dja Dja Wurrung people who seek to restore its presence across Country (Djandak) through broadacre seed crop production. To achieve this, agronomic challenges to establishment must be overcome.

To understand the effects of harvest time on seed viability and sowing time on crop establishment.

In Experiment 1, seed viability was assessed in a remnant Djandak stand in three seasons and seed colour assessed and cumulative seed shed measured in two of these seasons. In Experiment 2, seed from two Djandak ecotypes was sown at two sites at eight sowing dates over two seasons and plant emergence, culm number and canopy cover were recorded.

In Experiment 1, seed was shed from mid-December to late-January and seed viability varied intra- and inter-seasonally. Viability of early shed seed was low (0–24%) but increased with time to a peak of 68–69% in the first two seasons and 28–37% in the final season. Most seed had shed when peak viability was reached. Dark-coloured seeds with a caryopsis exhibited both high viability and high dormancy. In Experiment 2, sowing in September–October resulted in the optimal combination of highest mean establishment, lowest variability and no establishment failures.

To maximise crop establishment, seed should be sown in September–October on Djandak and be harvested when 30–50% of seed has shed.

These guidelines inform T. triandra establishment supportive of its development as a broadacre seed crop.

Keywords: crop agronomy, crop domestication, crop establishment, crop management, Indigenous plants, native grains, native grasses, perennial grains, seed production.

Introduction

Australian grasslands and grassy woodlands have been sustainably managed and used by First Nations people for millennia (Allen 1974; Tindale 1978; Balme et al. 2001; Pascoe 2014; Drake et al. 2021; Birch et al. 2023). Today, these biomes have been supplanted by exotic species largely associated with Western agriculture (Prober and Thiele 1995; Balme et al. 2001; Khoddami et al. 2020; Birch et al. 2023). Restoration of grasslands and grassy woodlands is critical for healthy Country (the lands, waterways, skies and seas to which First Nations Australians are deeply connected), yet remains a complex challenge. The development of native grasses into contemporary seed crops is one pathway being explored to support this restoration and could lead to the greater inclusion of locally adapted species in contemporary farming systems and the creation of socioeconomic opportunities for First Nations people supportive of self-determination (Shapter et al. 2008; Chivers et al. 2015; Henry 2019; Khoddami et al. 2020; Canning 2022; Abedi et al. 2023; Birch et al. 2023). A significant challenge in the development of native seed crops is the lack of knowledge surrounding their agronomic management in contemporary systems (Male et al. 2022).

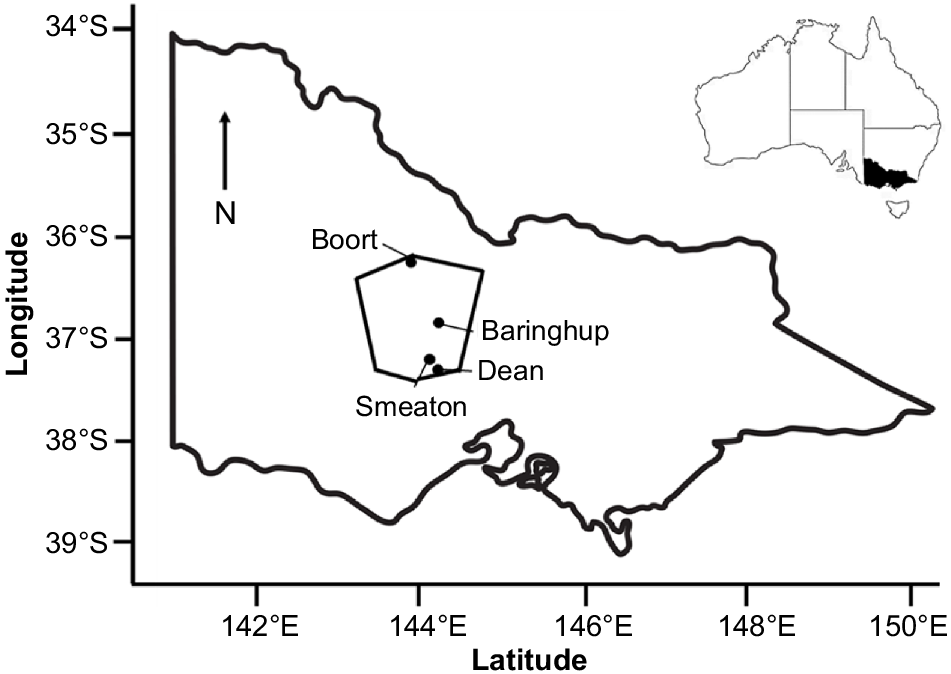

Themeda triandra, commonly known as kangaroo grass in Australia, is a widely distributed C4 perennial tussock grass naturally occurring in Australia, Africa, Asia and New Guinea (Hovenden and Morris 2002; Snyman et al. 2013). In Australia, the species is of cultural significance to the Dja Dja Wurrung people of Djandak (Dja Dja Wurrung Country in central Victoria) (Fig. 1). DJAARA, the Traditional Owner group representing Dja Dja Wurrung people, seek to increase agronomic knowledge of the species to support its development as a broadacre seed crop across Djandak. It is hoped that this will increase the presence of T. triandra across Djandak, with the potential for findings to be extended across Australia and globally where similar climatic conditions are experienced.

Location of Djandak (outlined), showing the location of the Experiment 1 remnant population (Smeaton), Experiment 2 study sites (Baringhup and Dean) and Experiment 2 ecotype locations (Boort and Smeaton).

Establishment of T. triandra in Australia for restoration purposes has been achieved through surface spreading of seed-bearing material, planting seedling tube stock and transplanting sods (McDougall 1989; Sindel et al. 1993; Cole et al. 2003; Cole and Lunt 2005; New South Wales Department of Primary Industries 2021a). However, these methods are costly, laborious, and impractical for large areas. Direct seeding using conventional or customised machinery is more efficient at a broadacre scale, but challenges of sowing seed with conventional seeding machines need to be managed (Merritt and Dixon 2011; Sampaio et al. 2019; Baskin and Baskin 2020; Berto et al. 2020; Male et al. 2022). Two factors that determine the success of T. triandra establishment when sown from seed are (i) the viability of the seed being sown, influenced by the time of seed harvest, and (ii) the time of sowing with respect to environmental conditions conducive to establishment.

The time of seed harvest is important for many agricultural crops because it influences resultant seed quality and yield. Like many native grasses, T. triandra experiences poor seed retention and asynchronous seed ripening (McDougall 1989; Baskin and Baskin 1998). This makes timing harvest challenging, unlike for many domesticated grasses that have good seed retention and uniform seed ripening supportive of a single harvest (Woodland 1964; McDougall 1989; Cole and Johnston 2006; Purugganan and Fuller 2009; Maity et al. 2021; Male et al. 2022). Themeda triandra’s asynchronous seed development is attributed to plant genetic and environmental factors. Within a plant, seeds ripen at differing times depending on their location on the inflorescence (Woodland 1964). Second, flowering and seed development rate is dependent on environmental conditions, predominantly soil moisture and temperature (Groves 1975; McDougall 1989; Snyman et al. 2013). This causes variation in ripening and seed shed between populations and seasons (McDougall 1989). At warmer and drier sites, T. triandra will shed seed earlier than at cooler and wetter sites. Between seasons, hotter and drier years will promote earlier seed shed, whereas cooler seasons will delay and prolong seed shed (McDougall 1989; Cole and Johnston 2006). Asynchrony of seed shed may be further influenced by plant genetics and vary between ecotypes, defined here as distinct genetic populations adapted to specific environmental conditions (Hill 1985; Stevens et al. 2020). Another barrier to establishment is that seed viability in natural T. triandra populations tends to be low, and the percentage of viable seed on a plant will change throughout seed shed (McDougall 1989; Snyman et al. 2013). Because of these factors, there is no single time when all seed will be ready for harvest within and among populations. Thus, harvest will be a compromise between harvesting as many ripe seeds as possible, and not harvesting too early (McDougall 1989). If seed is collected too early, the risk is that a large proportion of seed is likely to be immature and unviable, whereas if seed is collected too late, the risk is that a large proportion of seed risks being lost through seed shed (McDougall 1989). This presents the following two possible strategies for the harvest of T. triandra: (i) harvest multiple times over a season, or (ii) harvest once when collection of viable seed can be maximised. For the former, a non-destructive method of harvest that collects only ripe seeds is needed, along with a knowledge of how seed viability changes across the seed shed period. For the latter, knowledge of optimal harvest time to maximise the collection of viable seed is critical. On the basis of field experiments conducted on four remnant grasslands near Melbourne during 1986–1988, McDougall (1989) suggested that harvesting when 35–40% of seed in the crop has shed maximises the collection of viable seed. However, the author was uncertain whether this is consistent across locations, seasons and ecotypes. McDougall (1989) also indicated that dark-coloured seeds with a caryopsis are most likely to be viable, whereas white seeds lacking a caryopsis are likely to be unviable.

To maximise successful establishment from direct seeding, it is also necessary to identify the optimal time of sowing for T. triandra (Cole and Lunt 2005). As temperature and soil moisture are the key environmental factors influencing germination, growth and development of T. triandra, sowing should occur when these conditions are favourable in the targeted growing environment. The germination temperature range for T. triandra is approximated to be 15–45°C (Male et al. 2022). Germination rate and subsequent growth improve as soil moisture increases towards field capacity, with poor germination under water stress (Hagon and Chan 1977; Opperman and Roberts 1978; Groves et al. 1982; Nolan 1994; Stevens et al. 2020). The germination requirement of temperatures >15°C and good soil moisture is typical of C4 grasses (Clifton-Brown et al. 2011; Fan et al. 2012). Across Djandak, and much of temperate southern Australia, there is a seasonal mismatch between simultaneous occurrence of temperatures and soil moisture conducive to T. triandra germination. Favourable temperatures occur from spring to early autumn (September–April), whereas adequate soil moisture most reliably occurs from late autumn to early spring (May–October). Growth is further supported by the increased solar radiation experienced outside of winter (Hagon and Groves 1977; Sindel et al. 1993). These environmental requirements lead to natural T. triandra stands in southern Australia initiating renewed annual growth and development in spring, with rapid growth in late spring and summer (Evans and Knox 1969; Groves 1975; Danckwerts 1987; McDougall 1989; Snyman et al. 2013).

Here, we present the results of two experiments designed to quantify the effect of time of harvest and time of sowing on the establishment of T. triandra, with a geographic focus on Djandak. In Experiment 1, we examine the impact of harvest time on T. triandra seed viability to improve understanding of how T. triandra seed viability varies over the seed-shed period and to what extent readily observable characteristics can indicate optimal time of harvest. This is important because viable seed is scarce and required in large quantities to support broadacre establishment. In Experiment 2, we then quantify how time of sowing affects establishment, and whether effects vary among site, ecotype and year. Similarly, this is important to maximise the number of scarce viable seed contributing to establishment.

Materials and methods

Nomenclature

The true seed of T. triandra is the caryopsis (the fruit or grain), contained within the seed diaspore. The seed diaspore is the dispersal structure that contains the caryopsis, and consists of the awn, callus and the palea and lemma. Not all seed diaspores contain a caryopsis (Durnin et al. 2024). For this paper, the term ‘seed’ refers to the seed diaspore and the term ‘caryopsis’ refers to the fruit/grain. Seed colour refers to the colour of the palea and lemma, the husky structures that tightly enclose the space that a caryopsis can occupy. The term ‘culm’ refers to the tall reproductive seed-bearing structures of grasses and includes the stem and panicles.

Experiment 1 site description

Experiment 1 was conducted in a remnant T. triandra stand in southern Djandak near Smeaton, Victoria (37°30′S, 144°00′E) (Fig. 1). Throughout the experimental period (2020–2023), precipitation at the nearest Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) meteorological station (Smeaton (Blampied/Bardia), 37°34′S, 143°99′E, 1968–2024) was 138 mm (October–December 2020), 725 mm (2021), 989 mm (2022) and 6 mm (January, 2023) (Bureau of Meteorology 2024). Because this BoM station did not record temperature, we used the mean daily air temperatures at the nearby (13 km to the south-east) Dean site weather station used for Experiment 2, which was 14.0°C (October–December 2020), 11.5°C (2021), 12.0°C (2022) and 17.0°C (January 2023) (Supplementary Fig. S1). There was no soil description for this site because it was located on a roadside.

Experiment 2 site descriptions

Experiment 2 was conducted at two dryland sites on Djandak, namely, Baringhup and Dean (Fig. 1). Daily air temperature (°C), precipitation (mm) and solar radiation (W/m2) were logged at 30-min intervals at both sites throughout the experimental period by an onsite HoboLink HOBO RX2100 CELL-4G weather station.

The Baringhup site was in central Djandak (37°00′S, 144°00′E). The soil was a red Sodosol (Isbell 2021) located on a flat riverine plain overlain with younger alluvial sediments sourced from the adjacent Loddon River. The soil-profile horizon A1 0–18 cm was as follows: dark brown (7.5YR 3/2) very fine sandy loam; massive structure; weak consistency when dry; pH 7; abrupt and wavy change to next horizon. The nearby meteorological station (Bendigo Airport, ~40 km to the north-east, 36°74′S, 144°33′E, 1991–2024) experiences a mean annual maximum temperature of 21.2°C and mean annual precipitation of 510 mm (Bureau of Meteorology 2023a). Baringhup received 507 mm annual precipitation in 2021 and an above-average total of 849 mm in 2022. The mean air temperature was 14.0°C in 2021 and 14.8°C in 2022 (Fig. S2).

The Dean site was in southern Djandak (37°50′S, 144°00′E). The soil was a red Dermosol (Isbell 2021) located on a weathered-basalt (newer volcanics) gentle to moderate slope. The soil-profile horizon A1 0–20 cm was as follows: dark brown (7.5YR 3/2) clay loam; polyhedral to granular structure; weak to firm consistency when dry; fewer than 5% coarse fragments of weathered basalt (<5 mm); pH 4.5; clear and wavy change to next horizon. The nearby meteorological station (Ballarat Aerodrome, ~20 km to the south-west, 37°51′S, 143°79′E, 1908–2024) experiences a mean annual maximum temperature of 17.4°C and a mean annual precipitation of 688 mm (Bureau of Meteorology 2023b). Dean received above average annual precipitation in both 2021 (1013 mm) and in 2022 (941 mm). The mean air temperature was 11.5°C in 2021 and 12.0°C in 2022 (Fig. S2).

Experiment 1: optimal time of harvest

Themeda triandra seeds were collected across three seasons (December–January 2020–2021, 2021–2022 and 2022–2023) at approximately 1-week intervals across either seven (2022–2023) or eight (2020–2021 and 2021–2022) harvest dates beginning prior to seed shed and lasting until it finished. For each harvest date, 50–100 culms were collected across the population, with more culms collected at later harvest dates to account for losses from seed shed. Culms were removed by breaking from the parent plant below the panicle and placing in paper bags. Samples were placed in dry storage at ambient room temperature until being tested for viability 5 months after harvest in the first season (2020–2021), within 1 month of harvest in the second season (2021–2022) and 5 months after harvest in the third season (2022–2023). Seed colour was recorded as either white or dark (brown or black) for each of the seeds selected for use in the standard germination test.

There were 250 seeds sampled for each harvest date regardless of colour, size and presence of a caryopsis, and then de-awned and split into five replicates of 50 seeds. There were <250 seeds (<5 replicates, some with <50 seed) for the final two harvest dates in Season 2 (2021–2022) and the final harvest date in Season 3 (2022–2023) because of lack of seed. The first of two seed viability tests comprised a germination test. For each replicate, seeds were placed between two sheets of 70 mm diameter Whatman No. 1 filter paper inside a 90 mm diameter pre-sterilised Petri dish. Filter paper was saturated with 5 mL of distilled water. The replicates were placed in randomised positions on a rack in a controlled environment room for seed collections from the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 seasons (constant 28°C; 65% relative humidity; indirect light) and a growth chamber (Conviron Adaptis A-1000) for the seed collection from 2022–2023 (constant 28°C, no light). The presence of indirect light versus no light is not expected to affect germination (Hagon 1976; Baxter 1996). Distilled water was sprayed onto the filter paper when required to ensure it remained moist. Filter paper was replaced if fungal growth was observed. Seeds were scored for germination every 2–5 days for 21 days. Seeds were considered germinated if the radicle had emerged from the seed. At the conclusion of the experiment, all germinated seeds were considered to have a caryopsis and seeds without a caryopsis were discarded and considered unviable. The number of remaining ungerminated seeds with a caryopsis were recorded and the caryopses were removed from the husks with forceps. Caryopses were then tested for viability to determine the proportion of ungerminated seeds that were viable but dormant, by using a method derived from Hall et al. (2007) and Patil and Dadlani (2009). Caryopses were placed into 90 mm pre-sterilised Petri dishes and pre-conditioned by imbibing in distilled water and placing in a controlled environment room (constant 28°C; indirect light) for 24 h. A 100 mL 1% tetrazolium solution was prepared according to Patil and Dadlani (2009) and poured into the Petri dishes to partially submerge the caryopses before placement in an incubator at 40°C for 24 h. Following this, caryopses were dissected and inspected for patterns of red staining. Caryopses were deemed viable (dormant) if red staining was observed and caryopses with no (or very weak) staining were deemed unviable. In the results, germinated seeds are reported as ‘viable seed (non-dormant)’, or ‘viable seed (dormant)’ and ‘viable seed’ refers to total seed viability, inclusive of dormant and non-dormant seeds.

In the second and third seed-shed seasons (2021–2022 and 2022–2023), percentage seed shed at each harvest time was estimated by randomly placing five plastic trays (0.28 m width × 0.35 m length × 0.05 height, equating to a total area of 0.49 m2) throughout the T. triandra remnant population, as per McDougall (1989). At each harvest time, the number of seeds fallen into the trays was counted and seeds were collected. Cumulative seed shed was calculated as the sum of seed shed at each harvest time.

Experiment 2: optimal time of sowing

To test the importance of soil moisture for germination, soil water potential was measured by sampling seed bed soil (top 2 cm of the soil profile) on average every 9 days from October to February in the 2022–2023 season from three different areas within the experimental area at each site. Samples were placed into plastic snap lock bags and stored at 4°C until soil water analysis within 3 days of collection. Soil water potential was measured on three subsamples using a WP4 Dewpoint PotentiaMeter (Decagon Devices Inc., Washington, USA).

Themeda triandra seed was collected using a trailing brush harvester (Kimseed Australia, Wangarra, Western Australia) towed by a ute over the 2020–2021 seed-shed season from two geographically distant remnant stands on Djandak; one near Smeaton in southern Djandak (37°50′S, 144°00′E) and one near Boort in northern Djandak (36°10′S, 143°70′E) (Fig. 1). Although we cannot assert that these stands are genetically distinct, we refer to these as ‘ecotypes’ and have labelled according to their approximate locality of origin (Smeaton and Boort). Seed was air dried and placed into dry storage at ambient room temperature after field collection until sowing. Seeds that appeared dark (brown or black) in colour and felt hard when pressed between fingers (indicative of a caryopsis being present) were selected for sowing because these have the highest likelihood of being viable.

At each site, two experiments were conducted, consisting of eight time of sowing (TOS) treatments; one experiment used seed from the Smeaton ecotype and the other experiment used seed from the Boort ecotype (Table 1). There were no March or April TOS treatments for the Boort ecotype in 2021. Four replicates for each TOS were arranged in a randomised complete-block design and each replicate had 50 seeds buried at approximately 1 cm depth and 2 cm apart along a 1 m furrow opened with a stainless-steel table knife. The distance between each row was 0.5 m. Attempts were made to keep the area weed-free by hand-removal or herbicide application, but removal of emerged weeds within the sown rows was avoided to reduce seed displacement. The experiments were repeated over two field seasons (2021 and 2022) to give a total of four site years.

| TOS 2021 | TOS 2022 | Season | Phenology of natural stand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 MarchA | 14 March | Autumn | End of growth season | |

| 15 AprilA | 7 April | Autumn | Entering dormancy | |

| 19 May | 18 May | Autumn | Dormant | |

| 14 July | 13 July | Winter | Dormant | |

| 17 September | 27 September | Spring | Early growth season | |

| 14 October | 11 October | Spring | Early growth season | |

| 17 November | 17 November | Spring | Early growth season | |

| 14 December | 15 December | Summer | Mid growth season |

To compare establishment success among TOS, site, ecotype and year, the following three measurements were taken: (i) seedling emergence and survival, (ii) culm number, and (iii) percentage canopy coverage.

Seedling emergence and survival within each 1 m row were counted at regular intervals (at least once per month during the growth season and only once in winter) from the time of sowing onward. Seedlings were regarded as dead if they appeared brown and desiccated or were missing altogether having been previously noted. Counts ceased at the end of the growth season (March), henceforth referred to as ‘end of summer’. The percentage of sown seeds that emerged by the end of summer was calculated to give the total percentage plant emergence.

Culm number within each 1 m row was counted at the end of summer. Culm number at the end of the second summer was additionally recorded for experiments established in 2021.

The percentage canopy cover was recorded at the end of summer through visually assessing the percentage of each 1 m row that was covered by leaves, tillers or culms and scoring in 5–10% intervals from 0% (no canopy cover) to 100% (full canopy cover) (Fig. 2). Canopy cover at the end of the second summer was recorded for experiments established in 2021.

A restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) exploratory analysis was conducted using mixed linear models in Genstat (ver. 22; VSN International, Hempstead, UK) to test for the main effects of, and interactions among, TOS, site, ecotype and year. The percentage plant emergence at the end of summer was the response variate, block was the random effect and site, ecotype, year and TOS comprised the fixed model. The Wald statistic from the REML output was used to infer the percentage of variation explained by each main effect and their interactions.

A subsequent one-way ANOVA assuming randomised blocks was performed in Genstat to test for significant effects (P < 0.05) of TOS for each ecotype at each site in each year for percentage plant emergence, culm number and percentage canopy cover. If a significant difference was found, Fisher’s protected least significance difference was used to determine differences between predicted means at 5% significance level.

Results

Experiment 1: optimal time of harvest

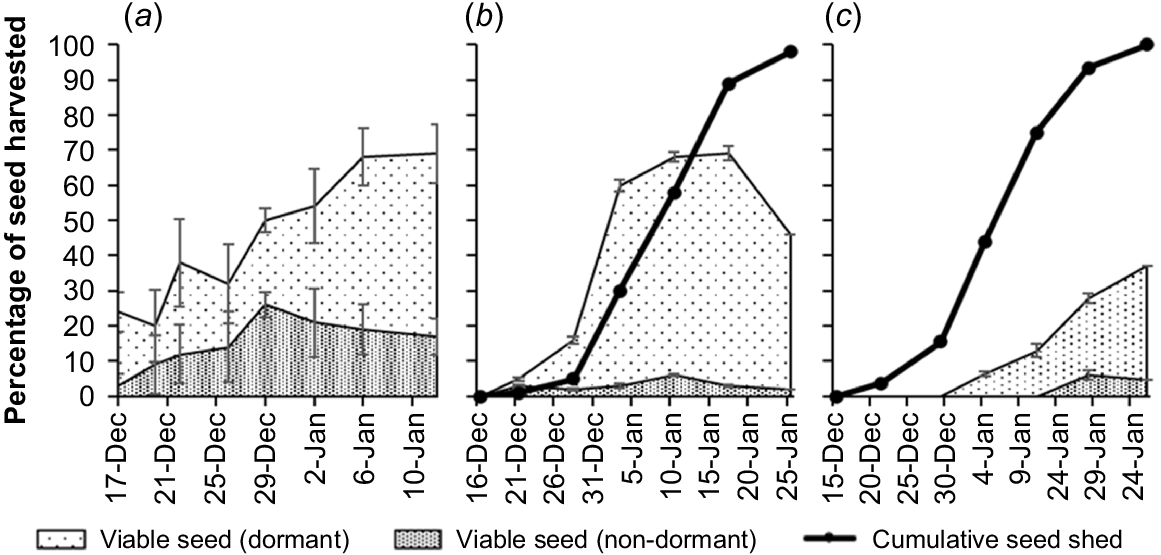

Across seed-shed seasons (i) seed shed began mid-December and was finished by late-January, (ii) seed viability was low early seed shed (0–24%) and peaked late seed shed (up to 69%), (iii) seed viability peaked at similar levels in the first two seasons (68–69%) but was much lower in the last season (28–37%) and, (iv) most seeds with a caryopsis were viable and dormant at the time of germination testing. A descriptive summary of each season follows.

In 2020–2021, seed viability was low at early seed shed (24%, 17 December) and peaked during late seed shed (68–69%, 6 January−12 January) (Fig. 3a). Most seeds with a caryopsis were viable (93 ± 2%, mean ± s.e.) but most viable seeds were dormant (66 ± 5%). No data were collected on cumulative seed shed or seed colour in the 2020–2021 season.

Mean percentage viable seed (dormant), viable seed (non-dormant) and cumulative seed shed in (a) 2020–2021, (b) 2021–2022 and (c) 2022–2023 seed-shed seasons. Dates on X axis vary among figures. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean.

In 2021–2022, 84% of seed shed occurred over a 3-week period (28 December−17 January) and was complete by 25 January (Fig. 3b). Seed viability was low at early seed shed (5% seed viability at 5% seed shed, 21 December) and peaked during mid–late seed shed (68–69% seed viability at 58–89% seed shed, 10 January−17 January). Most seeds with a caryopsis were viable (89 ± 4%) but most viable seeds were dormant (93 ± 1%).

In 2022–2023, 78% of seed shed occurred over a 3-week period (29 December−18 January) and was complete by 26 January (Fig. 3c). Seed viability was low at early seed shed (0% seed viability at <5% seed shed, 22 December) and peaked at late seed shed (28–37% seed viability at ~90–100% seed shed, 18 January−26 January). About half of the seeds with a caryopsis were viable (54 ± 9%), which was less than in the previous seasons. Viable seeds were again mostly dormant (88 ± 5%).

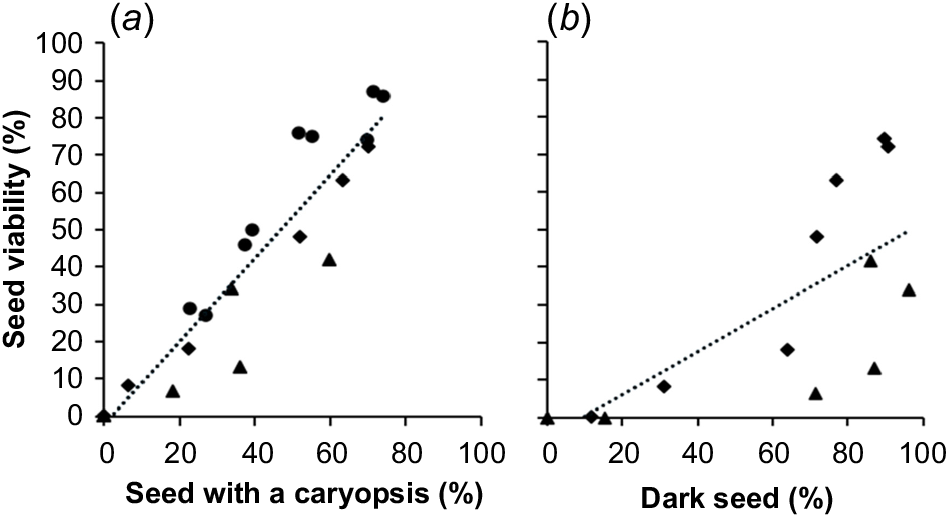

There was a significant strong positive relationship (P-value < 0.001, R2 = 0.88) between seed with a caryopsis and seed viability across all three seasons (Fig. 4a). Similarly, there was a significant strong positive relationship (P-value < 0.002, R2 = 0.56) between dark seed and seed viability across all three seasons (Fig. 4b).

The relationship between seed viability and (a) seed with a caryopsis (%) across three seed-shed seasons, and (b) dark seed (%) across two seed-shed seasons. 2020–2021 (●), 2021–2022 (♦), 2022–2023 (▲) seasons. Each point represents the mean across different harvest dates. The linear function fitted by least-squares regression is of the form: (a) y = 1.11x + 2.21 (R2 = 0.88), with lower and upper 95% confidence intervals being 0.92 and 1.3 for the slope and −10.8 and 6.4 for the constant, (b) y = 0.57 + 5.46 (R2 = 0.56), with lower and upper 95% confidence intervals being 0.252 and 0.894 for the slope and −26.85 and 15.94 for the constant.

Experiment 2: optimal time of sowing

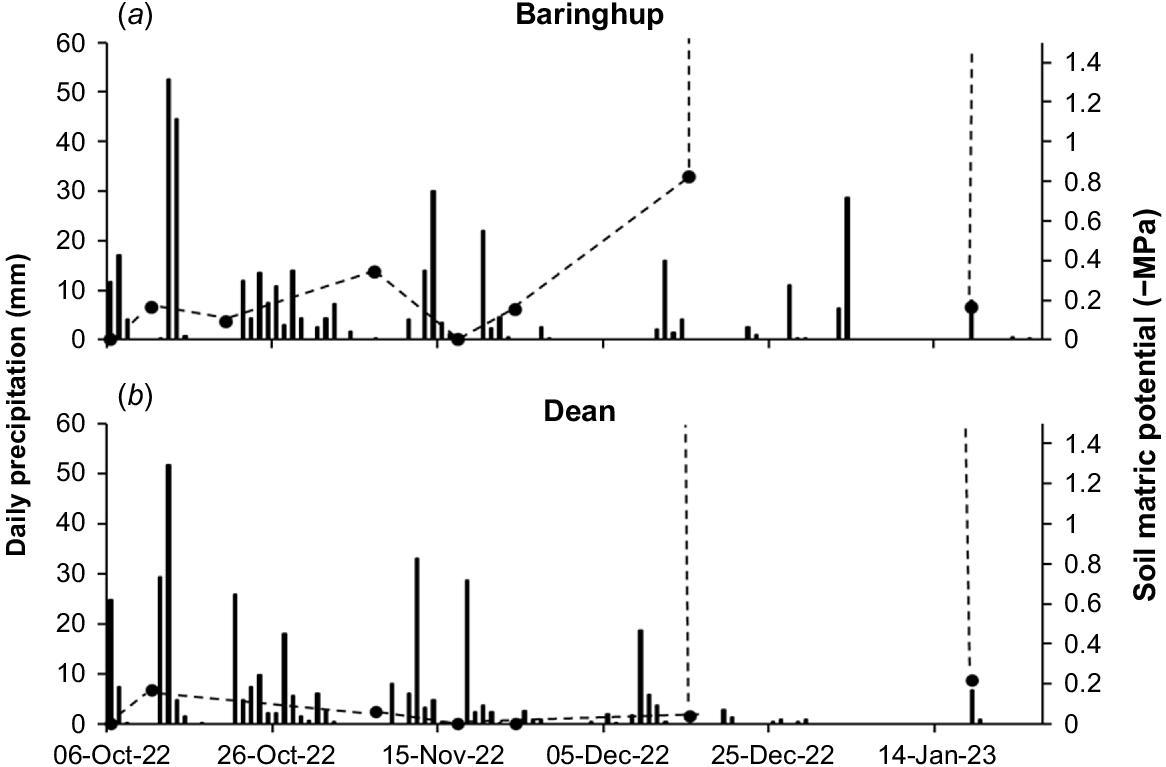

The germination rate of T. triandra seed significantly slows at a soil water potential of −1.0 MPa (Stevens et al. 2020). In other grasses, such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) and corn (Zea Mays), soil water potential greater than −1.2 to −1.5 MPa is necessary for germination (Wuest and Lutcher 2013; Walne et al. 2020). Here, we assume that a soil water potential of >−1.5 MPa is required for T. triandra germination. However, this is not known and the response of T. triandra seed to water stress may vary among ecotypes (Stevens et al. 2020). In the 2022 germination period, soil water potential was deemed sufficient for germination until mid-December (2022) where it then became too dry (<−1.5 MPa) for germination (except briefly following sporadic rain events) (Fig. 5a, b).

Daily precipitation (columns) and soil matric potential (dashed line with markers) over the germination period at (a) Baringhup and (b) Dean during October–January (2022–2023). Absence of line indicates that soil matric potential was not suitable for germination (>−1.5 MPa).

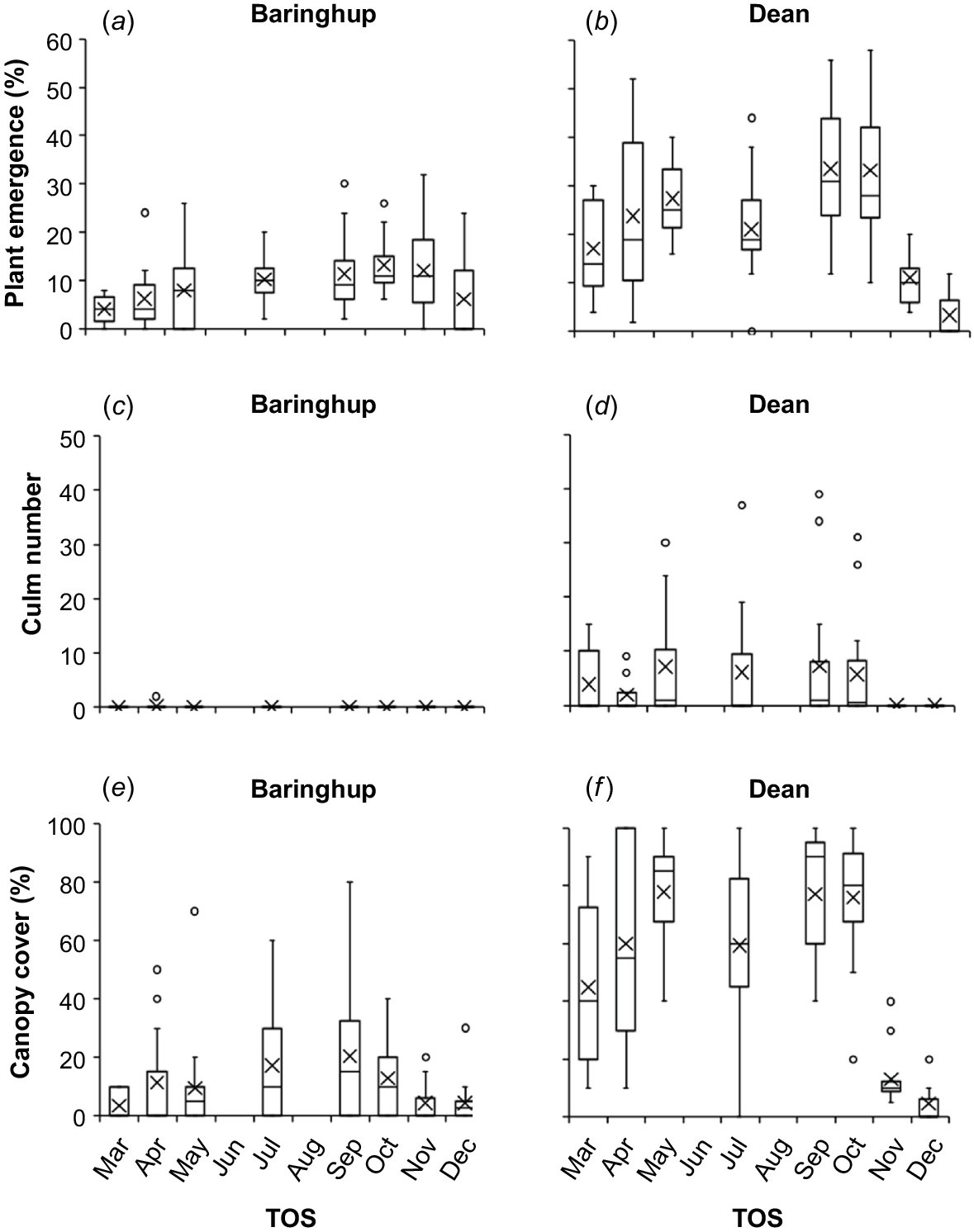

Site and TOS had a significant (P < 0.001) effect on plant emergence, which ranged between 0 and 54%, and explained the most single-factor variation (28% and 25% respectively). Site × TOS also had the strongest two-factor interaction, explaining 15% of the variation. Year × site × TOS had the strongest three-factor interaction, explaining 9% of the variation. Ecotype and year explained the least variation in plant emergence (2% and 1% respectively) (Supplementary Table S1). September and October TOS consistently had the highest mean and median plant emergence, being higher at Dean (Fig. 6). Generally, TOS outside September and October had lower and more variable plant emergence.

Box plots showing the plant emergence (%), culm number and canopy cover (%) at the end of summer dependent on time of sowing (TOS) and inclusive of both ecotypes (Smeaton and Boort) and sowing years (2021 and 2022) at (a, c, e) Baringhup and (b, d, f) Dean. × represents the mean, lines in the box represent the 25%, 50% (median) and 75% quartiles, whiskers represent the range and circles represent outliers. Categorical labels are used on X-axis because sowing dates varied slightly between years.

Culm number and canopy cover followed a pattern similar to that of plant emergence, with September–October TOS and the Dean site performing best. However, culms were produced at the end of the first summer only at one site in one year, being Dean in 2021.

September and October TOS similarly had consistently high and less varied plant emergence, culm number and canopy cover when analysed within site, year and ecotype in the ANOVA analysis (Table S2).

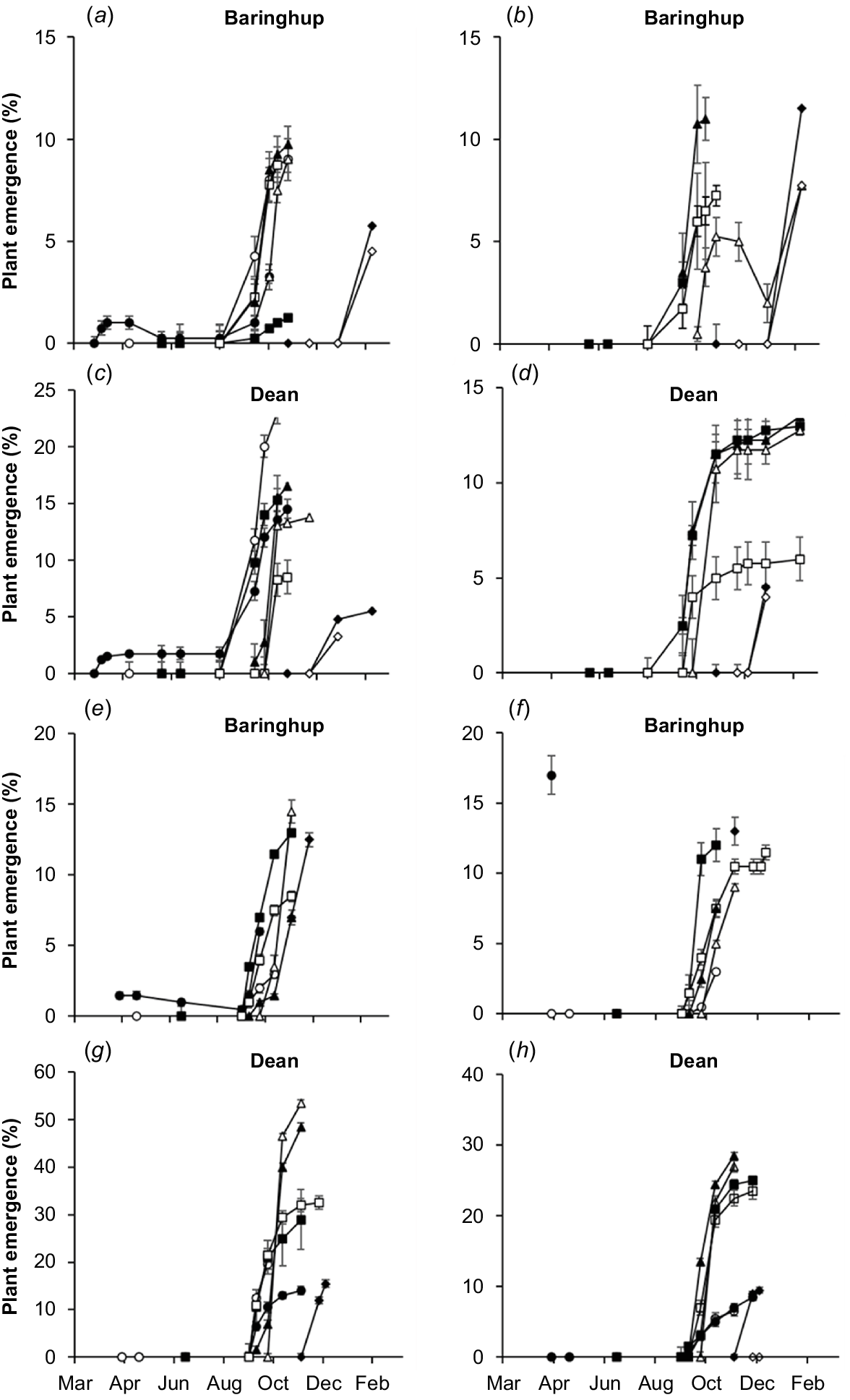

Most seed sown from autumn to early spring (March–October) emerged rapidly in early spring (September–October) (Fig. 7). There were cases where plants emerged from autumn TOS in the same autumn, but these seldom established, for example, the March TOS at Baringhup for the Smeaton ecotype in 2021 had 1% plant emergence in April, but this decreased to 0% in May (Fig. 7a).

Change in mean plant emergence (%) dependent on time of sowing (TOS), site, ecotype and year for (a) Smeaton ecotype, Baringhup, 2021, (b) Boort ecotype, Baringhup, 2021, (c) Smeaton ecotype, Dean, 2021, (d) Boort ecotype, Dean, 2021, (e) Smeaton ecotype, Baringhup, 2022, (f) Boort ecotype, Baringhup, 2022, (g) Smeaton ecotype, Dean, 2022, and (h) Boort ecotype, Dean, 2022. March (●), April (○), May (■), July (□), September (▲), October (Δ), November (♦), December (◊) represent times of sowing (TOS). The line ends at maximum plant emergence. Any decreases in plant emergence indicate the death of emerged plants. Absence of lines indicates no plant emergence. Y-axis varies among figures. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean.

TOS treatments with poor establishment at the end of the first summer had poor canopy cover at the end of the second summer. For example, the December TOS at Dean for the Smeaton ecotype in 2021 only had 6% plant emergence at the end of the first summer and, subsequently, only 4% canopy cover at the end of the second summer (Table S2).

Discussion

This study aimed to increase knowledge of the optimal time of T. triandra seed harvest and sowing, with a focus on the Djandak region of southern Australia.

Optimal harvest time

We found that T. triandra seed viability varied within a seed-shed season, being low at the beginning and improving as the season progressed. Because of the low seed viability early in seed shed and harvest being costly and labour-intensive, we argue that a one-time harvest (rather than multiple harvests) is the preferred harvest strategy and should be delayed to when 30–50% of seed has shed. This compromise of harvesting less seed, but with higher viability, is a further refinement to the recommendation made by McDougall (1989) to use 35–40% seed shed as a guide to optimum harvest time. Furthermore, our results are supportive of McDougall (1989) who found that seed viability in T. triandra populations outside Djandak and near Melbourne peak late in seed shed. Therefore, harvest will differ from that of domesticated cereal crops, such as wheat, which occurs when most seed is retained. Future research aimed at improved T. triandra seed retention should be a priority to maximise the collection of viable seed from a one-time harvest, such as the use of tacking agents (e.g. polyvinyl acetate) or plant breeding aimed at promoting uniform seed ripening and greater seed retention, as seen in forage perennial grasses and domesticated cereals (McDougall 1989; Oram et al. 2009; Maity et al. 2021).

To inform the optimal time of a single harvest, our findings highlighted the importance of closely monitoring T. triandra from the onset of seed shed. Readily observable characteristics to monitor include percentage of seed shed, seed colour and the presence of a caryopsis. Across Djandak, these indicators should be monitored from mid-December, and possibly earlier in more northerly sites that experience warmer temperatures as well as in warmer seasons. An easy and practical monitoring method for a one-time harvest is to conduct regular assessment of culms representative of crop development and check for 30–50% of spikelets being empty of seed, seed being dark in colour (with an attached black awn) and a feeling of the seed being hard or full when pressed between fingers. An additional method to assess seed shed could be to place several containers on the soil surface beneath a crop, and harvest soon after the observance of dark and filled seed in the containers. This should typically correspond to >30% seed shed because much of the early seed shed will be white and/or unfilled.

Although we found that seed viability peaked at similar times across seasons, and consistently at 69% in the first two seasons, this peak was considerably lower in the third season. We speculate that this is a result of seasonal weather variation, with the third season being notably wetter than the prior two seasons during flowering; for example, the nearest BoM meteorological station recorded 382 mm (October–December 2022–2023) compared with 148 mm (October–December 2021–2022) and 138 mm (October–December 2020–2021). As temperatures across the three seasons were similar, this suggests that higher-rainfall years may have a negative effect on seed viability. This could be due to reduced solar radiation associated with increased cloud cover and a subsequent reduction in net photosynthetic rate and possible chilling damage that can affect seed development and reduce seed yield, as has been observed in cereals (Demotes-Mainard et al. 1995; Shi et al. 2022; Slafer et al. 2023).

Our results indicated that, although most seeds with a caryopsis were viable, the majority did not germinate during germination tests conducted in the 1–5 month period following harvest. This is similar to the findings of Everson et al. (2009) and Baxter (1996), namely that T. triandra seed can have high viability but low germinability owing to dormancy, and further confirmed that freshly harvested T. triandra seed is mostly dormant and requires dormancy to be broken ahead of sowing (Everson et al. 2009; Saleem et al. 2009). There are several known techniques with varied effectiveness in breaking T. triandra seed dormancy, including after-ripening, the use of fire and smoke, addition of gibberellic acid and temperature stratification (Groves et al. 1982; Baxter et al. 1994; Ghebrehiwot et al. 2012; Male et al. 2022). However, the effectiveness of these techniques is inconsistent (Durnin et al. 2024). After-ripening is likely to have the lowest cost and is a logistically easy technique, being reliant solely on the storage of seed over a period of time (Baskin and Baskin 1977, 1983, 1985; Baxter 1996; Saleem et al. 2009; Male et al. 2022). However, caution is needed as T. triandra seed has been found to lose viability during prolonged storage, beginning as early as 10 months (Baxter 1996; Mason 2005; Everson et al. 2009). Storage at cool temperatures can maintain seed viability for longer, but this comes at the cost of reducing after-ripening and thus slower relief of dormancy (Baxter 1996). In addition, low seed moisture can improve further the longevity of viable seed in storage (Baxter 1996). Seed dormancy is known to vary among ecotypes; therefore, identification of ecotypes with a lower seed dormancy is another pathway to overcome germinability challenges (Baxter 1996; Stevens et al. 2020).

If seeds with a caryopsis are to be used as a food product, then an earlier one-time harvest may be suitable because viability is less of a concern and a greater quantity of seed is desired. However, much of the early seed shed still lacks a caryopsis. An important aspect here that will need to be addressed through future research is how harvest time may affect the food properties of the seed, for example, its taste, nutrition and ability to be processed.

Optimal sowing time

Seed sown ahead of, or during, early spring resulted in the highest and most reliable establishment. In particular, September and October TOS had the highest mean and median and lowest-risk establishment across ecotype, site and year. This was expected as seeds require adequate topsoil moisture (>−1.5 MPa) and consistent warm temperatures >15°C to germinate. At Baringhup and Dean, these conditions rarely coincided in autumn and winter but did consistently in early spring (September–October).

Autumn–winter TOS (March–July) were more variable but achieved mean establishment similar to T. triandra sown in September and October following delayed germination, with most seed remaining ungerminated until favourable germination conditions in the subsequent spring. In some cases, plants emerged from autumn-sown seed during the same autumn, supportive of previous reports that T. triandra seed can germinate in autumn (New South Wales Department of Primary Industries 2021b). However, autumn-emerged plants had low survival over the winter months, demonstrative of their susceptibility to unfavourable winter conditions, such as frost, whereas spring-emerged plants had higher survival in response to consistent environmental conditions conducive not only to germination, but also to early growth and development (Hagon and Groves 1977; Sindel et al. 1993; Male et al. 2022).

Shallow sowing depth is typically required to maximise establishment of C4 perennial pastures grasses, such as switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) (Wolf and Fiske 2009; Fan et al. 2012). This is similar for T. triandra, which requires a sowing depth of <2 cm (Sindel et al. 1993; Cole and Lunt 2005). Late spring–early summer TOS (November and December) had the lowest establishment, because higher temperatures experienced in these months (mean daily maximum temperatures >20°C), albeit supportive for germination and growth, resulted in rapid topsoil drying (<−1.5 MPa water potential) unsupportive of germination and emergence. It is plausible that sporadic rain events could lead to germination of seed planted in November and December. However, Stevens et al. (2020) demonstrated that at 25–30°C/15–20°C, 12 h/12 h day/night cycle, T. triandra requires 6 days with soil water potential near field capacity (0 MPa) to reach 50% germination, and this slows rapidly to 20 days at −1.0 MPa. Given the very rapid evaporation from the top 10 mm of soil experienced at this time of year, the chances of conditions suitable for germination occurring in the field are low. Irrigation could overcome water stress, but there is limited opportunity for this across Djandak and dryland cropping regions generally. Mulching or the application of biochar (Razzaghi et al. 2020) are other options that can promote the retention of soil moisture and improve establishment, but care is needed with mulching to prevent shading out of emerging plants (Hagon and Groves 1977; Winkel et al. 1991; Cole and Lunt 2005). Furthermore, predation of T. triandra caryopses, particularly by ants, has been found to be more severe in warmer months, such as in late spring (November) (Everson et al. 2009).

Our results found that establishment was greater at Dean in both years. This was likely to be due to higher surface soil moisture from cooler air temperatures and higher rainfall experienced in that environment, along with its higher soil clay content supportive of soil moisture retention. This again highlights the influence of environmental factors on T. triandra establishment, and perhaps explains its greater occurrence in higher rainfall areas in Australia (>450 mm annual rainfall).

We note that future climate change has the potential to shift the seasonal time of harvest and sowing across Djandak. For example, optimal time of harvest and sowing may creep earlier in the season with projected increased temperatures. Hence, it is of greater importance to understand the fundamental biology of T. triandra to inform seasonal optimal time of harvest and sowing, rather than any focus on a specific date. As such, a useful area of future research could be to model the optimal time of harvest and sowing for any target environment, by using climate predications for that environment.

Conclusions

We conclude that time of seed harvest and sowing determines the success of T. triandra establishment on Dja Dja Wurrung Country (Djandak). On the basis of our findings, T. triandra crop should be regularly monitored from the onset of seed shed to target a one-time harvest, when the highest number of viable seeds can be collected. Such harvest should be strategically guided by monitoring readily observable characteristics, such as percentage seed shed, seed colour and the presence of a caryopsis. Our results confirmed that viable seed is mostly dormant following fresh harvest and will require breakage of dormancy prior to sowing, and that seasonal weather variation can affect peak percentage seed viability. Our results emphasise the importance of sowing at a time when seasonal conditions in the target environment are conducive to germination and growth. Importantly, this is when sustained good surface soil moisture (soil water potential >−1.5 MPa) and warm temperatures (>15°C) are most likely to coincide. On Djandak, this was in early spring (September–October) when sowing at this time resulted in the highest and most reliable plant establishment. We hope these findings will not only support Dja Dja Wurrung in their vision to return T. triandra to Country but also stimulate further agronomic research and development supportive of the greater inclusion of native grasses into contemporary Australian farming systems.

Data availability

The data that support this study has an attached Local Contexts BC Label that governs its availability, as below.

BC label

The BC (Bio-Cultural) notice is a visible notification that there are accompanying cultural rights and responsibilities that need further attention for any future sharing and use of this material. The BC Notice may indicate that BC Labels are in development and their implementation is being negotiated. The BC Notice recognises the rights of Indigenous peoples to permission the use of information, collections, data and digital sequence information (DSI) generated from the biodiversity or genetic resources associated with traditional lands, waters, and territories.

Local Contexts ID: 01c1715f-6388-41a6-a020-a8694bad80a0.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of funding

This study was a part of the DJAARA-led ‘Djandak Dja Kunditja/Country healing its home’ project. We are grateful for financial support from the Australian Government’s Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment (DAWE), who awarded funding to DJANDAK, a commercial arm of DJAARA, through their ‘Smart Farms’ program. The research was further supported through an Australian Government Rural Training Program Scholarship and support from La Trobe University and the University of Melbourne. The authors express their gratitude and thanks to The Dr Albert Shimmins Fund for supporting the write-up of this paper.

Acknowledgements

Field experiments were conducted on Djandak, the traditional lands of Dja Dja Wurrung people. The authors recognise the enduring knowledge authority of Dja Dja Wurrung people. The authors acknowledge and gratefully thank Associate Professor John Morgan from La Trobe University, whose edits and comments helped improve an early version of this paper.

References

Abedi F, Keitel C, Khoddami A, Marttila S, Pattison AL, Roberts TH (2023) Indigenous Australian grass seeds as grains: macrostructure, microstructure and histochemistry. AoB Plants 15(6), plad071.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Allen H (1974) The Bagundji of the Darling Basin: cereal gatherers in an uncertain environment. World Archaeology 5(3), 309-322.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Balme J, Garbin G, Gould R (2001) Residue analysis and palaeodiet in arid Australia. Australian Archaeology 53(1), 1-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baskin JM, Baskin CC (1977) Germination ecology of Sedum pulchellum Michx. (Crassulaceae). American Journal of Botany 64(10), 1242-1247.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baskin JM, Baskin CC (1983) Germination ecology of Veronica arvensis. The Journal of Ecology 71, 57-68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baskin JM, Baskin CC (1985) The annual dormancy cycle in buried weed seeds: a continuum. BioScience 35(8), 492-498.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baskin CC, Baskin JM (2020) Breaking seed dormancy during dry storage: a useful tool or major problem for successful restoration via direct seeding? Plants 9(5), 636.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baxter BJM, Van Staden J, Granger JE, Brown NAC (1994) Plant-derived smoke and smoke extracts stimulate seed germination of the fire-climax grass Themeda triandra. Environmental and Experimental Botany 34(2), 217-223.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Berto B, Erickson TE, Ritchie AL (2020) Flash flaming improves flow properties of Mediterranean grasses used for direct seeding. Plants 9(12), 1699.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Birch J, Benkendorff K, Liu L, Luke H (2023) The nutritional composition of Australian native grains used by First Nations people and their re-emergence for human health and sustainable food systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 7, 1237862.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bureau of Meteorology (2023a) Climate statistics for Australian locations, summary statistics for Bendigo Airport. Available at http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_081123.shtml

Bureau of Meteorology (2023b) Climate statistics for Australian locations, summary statistics for Ballarat Aerodrome. Available at http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_089002.shtml

Bureau of Meteorology (2024) Weather station directory. Available at http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/data/stations/

Canning AD (2022) Rediscovering wild food to diversify production across Australia’s agricultural landscapes. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6, 865580.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clifton-Brown J, Robson P, Sanderson R, Hastings A, Valentine J, Donnison I (2011) Thermal requirements for seed germination in Miscanthus compared with Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinaceae), Maize (Zea mays) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). GCB Bioenergy 3(5), 375-386.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cole IA, Johnston WH (2006) Seed production of Australian native grass cultivars: an overview of current information and future research needs. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 46(3), 361-373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cole I, Lunt ID (2005) Restoring kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) to grassland and woodland understoreys: a review of establishment requirements and restoration exercises in south-east Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 6(1), 28-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cole I, Koen T, Metcalfe J, Johnston W, Mitchell M (2003) Tolerance of Austrodanthonia fulva, Microlaena stipoides and Elymus scaber seedlings to nine herbicides. Plant Protection Quarterly 18(1), 18-22.

| Google Scholar |

Danckwerts JE (1987) The influence of tiller age and time of year on the growth of Themeda triandra and Sporobolus fimbriatus in semi-arid grassveld. Journal of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa 4(3), 89-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Demotes-Mainard S, Doussinault G, Meynard JM (1995) Effects of low radiation and low temperature at meiosis on pollen viability and grain set in wheat. Agronomie 15(6), 357-365.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Drake A, Keitel C, Pattison A (2021) The use of Australian native grains as a food: a review of research in a global grains context. The Rangeland Journal 43(4), 223-233.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Durnin M, Dalziell E, Prober SM, Marschner P (2024) Variable seed quality hampers the use of Themeda triandra (Poaceae) for seed production, agriculture, research and restoration: a review. Australian Journal of Botany 72, BT24011.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Evans LT, Knox RB (1969) Environmental control of reproduction in Themeda australis. Australian Journal of Botany 17(3), 375-389.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Everson TM, Yeaton RI, Everson CS (2009) Seed dynamics of Themeda triandra in the montane grasslands of South Africa. African Journal of Range & Forage Science 26(1), 19-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fan J-W, Du Y-L, Turner NC, Li F-M, He J (2012) Germination characteristics and seedling emergence of switchgrass with different agricultural practices under arid conditions in China. Crop Science 52(5), 2341-2350.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ghebrehiwot HM, Kulkarni MG, Kirkman KP, Van Staden J (2012) Smoke and heat: influence on seedling emergence from the germinable soil seed bank of mesic grassland in South Africa. Plant Growth Regulation 66(2), 119-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Groves RH (1975) Growth and development of five populations of Themeda australis in response to temperature. Australian Journal of Botany 23(6), 951-963.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Groves RH, Hagon MW, Ramakrishnan PS (1982) Dormancy and germination of seed of eight populations of Themeda australis. Australian Journal of Botany 30(4), 373-386.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hagon MW (1976) Germination and dormancy of Themeda australis, Danthonia spp., Stipa bigeniculata and Bothriochloa macra. Australian Journal of Botany 24(3), 319-327.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hagon MW, Chan CW (1977) The effects of moisture stress on the germination of some Australian native grass seeds. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 17(84), 86-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hagon MW, Groves RH (1977) Some factors affecting the establishment of four native grasses. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 17(84), 90-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hall M, Delpratt J, Gibson-Roy P (2007) Viability testing of Victorian western plains grasses. Australasian Plant Conservation: Journal of the Australian Network for Plant Conservation 15(3), 23-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Henry RJ (2019) Australian wild rice populations: a key resource for global food security. Frontiers in Plant Science 10, 1354.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hill BD (1985) Persistence of temperate perennial grasses in cutting trials on the central slopes of New South Wales. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 25(4), 832-839.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hovenden MJ, Morris DI (2002) Occurrence and distribution of native and introduced C4 grasses in Tasmania. Australian Journal of Botany 50(6), 667-675.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Isbell R (2021) ‘The Australian soil classification.’ 3rd edn. (CSIRO Publishing, National Committee on Soils and Terrain) 10.1071/9781486314782

Maity A, Lamichaney A, Joshi DC, Bajwa A, Subramanian N, Walsh M, Bagavathiannan M (2021) Seed shattering: a trait of evolutionary importance in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 12, 657773.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Male D, Hunt J, Celestina C, Morgan J, Gupta D (2022) Themeda triandra as a perennial seed crop in south-eastern Australia: what are the agronomic possibilities and constraints, and future research needs? Cogent Food & Agriculture 8(1), 2153964.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Merritt DJ, Dixon KW (2011) Restoration seed banks – a matter of scale. Science 332(6028), 424-425.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (2021a) Grassed up – general guidelines for seed production. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/pastures-and-rangelands/rangelands/publications-and-information/grassedup/seed-production

New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (2021b) Grassed up – guidelines for revegetating with Australian native grasses. Themeda triandra (Kangaroo grass) species information. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/pastures-and-rangelands/rangelands/publications-and-information/grassedup/species/kangaroo-grass

Opperman DPJ, Roberts BR (1978) Die fenologiese ontwikkeling van Themeda triandra, Elyonurus argenteus en Heteropogon contortus onder veldtoestande in die sentrale oranje-vrystaat. Proceedings of the Annual Congresses of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa 13(1), 135-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Oram RN, Ferreira V, Culvenor RA, Hopkins AA, Stewart A (2009) The first century of Phalaris aquatica L. cultivation and genetic improvement: a review. Crop & Pasture Science 60(1), 1-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Prober SM, Thiele KR (1995) Conservation of the grassy white box woodlands: relative contributions of size and disturbance to floristic composition and diversity of remnants. Australian Journal of Botany 43(4), 349-366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Purugganan MD, Fuller DQ (2009) The nature of selection during plant domestication. Nature 457(7231), 843-848.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Razzaghi F, Obour PB, Arthur E (2020) Does biochar improve soil water retention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geoderma 361, 114055.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saleem A, Hassan F, Manaf A, Ahmedani M (2009) Germination of Themeda triandra (Kangaroo grass) as affected by different environmental conditions and storage periods. African Journal of Biotechnology 8(17), 4094-4099.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sampaio AB, Vieira DLM, Holl KD, Pellizzaro KF, Alves M, Coutinho AG, Cordeiro A, Ribeiro JF, Schmidt IB (2019) Lessons on direct seeding to restore Neotropical savanna. Ecological Engineering 138, 148-154.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shi Y, Guo E, Cheng X, Wang L, Jiang S, Yang X, Ma H, Zhang T, Li T, Yang X (2022) Effects of chilling at different growth stages on rice photosynthesis, plant growth, and yield. Environmental and Experimental Botany 203, 105045.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sindel BM, Davidson SJ, Kilby MJ, Groves RH (1993) Germination and establishment of Themeda triandra (kangaroo grass) as affected by soil and seed characteristics. Australian Journal of Botany 41(1), 105-117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Slafer GA, Savin R, Sadras VO (2023) Wheat yield is not causally related to the duration of the growing season. European Journal of Agronomy 148, 126885.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Snyman HA, Ingram LJ, Kirkman KP (2013) Themeda triandra: a keystone grass species. African Journal of Range & Forage Science 30(3), 99-125.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stevens AV, Nicotra AB, Godfree RC, Guja LK (2020) Polyploidy affects the seed, dormancy and seedling characteristics of a perennial grass, conferring an advantage in stressful climates. Plant Biology 22(3), 500-513.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Walne CH, Gaudin A, Henry WB, Reddy KR (2020) In vitro seed germination response of corn hybrids to osmotic stress conditions. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 3(1), e20087.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Winkel VK, Roundy BA, Cox JR (1991) Influence of seedbed microsite characteristics on grass seedling emergence. Journal of Range Management 44(3), 210-214.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wolf DD, Fiske DA (2009) Planting and managing switchgrass for forage, wildlife, and conservation. Virginia Cooperative Extension. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10919/50258

Woodland PS (1964) The floral morphology and embryology of Themeda australis (R.Br.) Stapf. Australian Journal of Botany 12(2), 157-172.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wuest SB, Lutcher LK (2013) Soil water potential requirement for germination of winter wheat. Soil Science Society of America Journal 77(1), 279-283.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |