The effect of pasture-based dam-rearing on attention bias after disbudding in dairy calves

Sandra Liliana Ospina Rios A * , Caroline Lee

A * , Caroline Lee  B , Sarah Jane Andrewartha

B , Sarah Jane Andrewartha  A and Megan Verdon

A and Megan Verdon  A

A

A

B

Abstract

Keeping cows and calves together promotes natural behaviours, improving calf growth and welfare. In other species, the dam’s presence reduces stress and improves offspring emotional affect when challenged. The impact of dam-rearing on calves’ ability to cope with painful procedures such as disbudding has not yet been investigated.

This study explored whether pasture-based dam-rearing influenced dairy calf behavioural responses indicative of affective state in an attention bias test (ABT) following disbudding.

Ten calves (Friesian, Friesian × Jersey) were separated from their dam at birth and group-reared indoors (commercial calves). Twelve calves remained with their dam at pasture (dam-reared calves). The calves underwent hot-iron disbudding at 6 weeks of age under sedation, local anaesthesia, and analgesic. The ABT was conducted 6 h post-disbudding, through exposing calves to a perceived threat for 10 s (i.e. a dog), and measuring their behavioural responses in the 3-min after threat removal. The effects of rearing treatment following disbudding were analysed using linear mixed models and Poisson regressions.

Commercial calves had more eating events in the 3-min following the dog’s removal (1.8 ± 1.99 vs 0.2 ± 0.60 eating events, P < 0.05), but there were no differences in attention or vigilance behaviour.

Under the conditions of this study, dam-rearing did not alter behavioural responses indicative of anxiety in an ABT. More research is recommended to fully elucidate whether affective experiences of calves are altered during painful husbandry procedures as a result of dam rearing versus commercial rearing systems.

The method of rearing did not affect negative affective states (i.e. anxiety) in a post-disbudding ABT. The stress from isolation, pain, or transportation may have influenced the results. Future methods should test calf affect without removing them from their treatment environment to better understand emotional experiences in dam-rearing systems.

Keywords: anxiety, cow–calf contact, dairy cattle behaviour, dam presence, emotional state, half-day contact, pastoral, pasture-based behavioural test, stressful events.

Introduction

Under typical Australian commercial conditions, dairy calves are removed from their dam within 24 h of birth and reared artificially in groups of similarly aged animals. The practice of separating dairy calves from their dams soon after birth aims to reduce cow–calf disease transmission, ensure that calves consume enough high-quality colostrum, gain control of calf health and avoid cow–calf bonding that leads to a future stressful separation (Flower and Weary 2003; Godden 2008; Beaver et al. 2019; Meagher et al. 2019). Keeping cows and calves together allows for more natural maternal behaviours, which can enhance calf growth, improve social development, and reduce stress in both cow and calf, ultimately contributing to better welfare outcomes and potentially improved long-term productivity (Meagher et al. 2019). Beyond the welfare benefits already highlighted in literature, increasing public interest in humane animal practices has driven interest in cow–calf contact systems, which may support not only calf welfare but also reinforce the maternal bond, benefiting both the cow and calf. However, few studies have explored how cow–calf contact (CCC) affects calf responses to routine procedures such as disbudding, leaving an important gap in understanding the potential role of CCC in reducing stress during such events.

Disbudding is painful as indicated through measures of behaviour (Faulkner and Weary 2000), physiology (Stafford and Mellor 2011) and affective states, with induction of negative emotional states and pessimism, even in sedated and locally anaesthetised calves (Neave et al. 2013; Daros et al. 2014). The administration of a local anaesthetic before the procedure delays the rise in cortisol following disbudding by approximately 2 h, but the stress hormone increases rapidly once the anaesthetic wears off (McMeekan et al. 1999). Behavioural evidence suggests calf aversion to hot-iron disbudding by using a place-conditioning paradigm, even with the use of a local anaesthetic (Ede et al. 2019), and wound sensitivity for up to 75 h following hot-iron cautery disbudding (Mintline et al. 2013). Painful dehorning procedures can also lead to negative emotional responses such as reduced play occurring for up to 44 h after the event (Huber et al. 2013; Mintline et al. 2013; Costa et al. 2019).

Social context can alter stress and pain perception in animals via social buffering. Social buffering refers to the reduction of an animal’s behavioural and physiological stress responses owing to the presence of affiliative social partners, such as a peer or dam (Kiyokawa and Hennessy 2018). This effect has been observed in several species, including rodents, canines, fish, primates and livestock (Hennessy et al. 2009). For example, pair-housed dairy calves resume eating more quickly after disbudding than do individually housed calves, suggesting faster recovery (Bučková et al. 2022). Similarly, mother-reared monkeys have shown increased social contact, reduced stereotypic behaviour and lower cortisol responses to a novel environment when a social companion is available, compared with nursery-reared monkeys (Winslow et al. 2003). The mother’s presence is particularly effective at reducing stress-induced cortisol concentrations in offspring. This has been reported in juvenile humans, monkeys, guinea pigs, rats, sheep, dogs and zebra finch (reviewed by Hennessy et al. (2009)). Cow–calf dairy systems may reduce the emotional impact of stressful or painful husbandry procedures such as disbudding on the calf, but this has not been studied.

Affective states, such as anxiety, can be assessed through an attention bias test (ABT). The ABT assesses the allocation of attention towards a potential threat (i.e. dog) and has been validated to assess anxious states in cattle (Lee et al. 2018). This provides insights into the emotional state of the subjects by measuring behaviours such as vigilance, the frequency and duration of gaze towards a stimulus (i.e. attention), and latency to eat. Increased vigilance and direction of attention towards a threat indicate heightened anxiety, whereas quicker resumption of eating and less attention towards a threat indicate lower anxiety levels (Lee et al. 2016). Animals experiencing threatening stimulus (i.e. predator threat) exhibit increased vigilance and altered attention patterns, validating the sensitivity of ABTs to detect these states (Monk et al. 2023).

The aim of this study was to explore the effect of pasture-based dam-rearing on the behavioural responses of dairy calves in an ABT after undergoing disbudding. It was hypothesised that dam rearing would reduce calves’ negative emotional response to disbudding during an ABT.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement and animal welfare

All animal procedures were conducted with prior institutional animal ethics approval (University of Tasmania Animal Ethics Committee A0024805) under the requirements of the Tasmanian Animal Welfare Act (1993) and following the National Health and Medical Research Council/Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation/Australian Animal Commission Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

Animals and experimental design

The research was performed at the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture Dairy Research Facility at Elliot (41°08′S, 145°77′E; 155.0 m amsl) in North-West Tasmania, Australia. Twenty-two dairy female calves (Friesian and Friesian × Jersey) were reared in groups with or without dam contact. In the dam-reared group (n = 12 cow–calf pairs), the calves were kept together with their dams at pasture during daylight hours and were separated from the dam but with fence-line contact and no suckling allowed during the night (half-day contact). Dam-reared calves spent the night in a paddock-based pen that included two shelters and were housed in groups of 16 with four cow–calf pairs that were not enrolled in this study. The commercial group (n = 10 calves) were separated from their dams soon after birth and reared in a single group of 14 calves with four calves not enrolled in this study within a semi-enclosed barn with natural ventilation and light, fed via a robotic feeder and offered 8 L of milk per day (DeLaval automatic calf feeder CF 150). All calves in both systems had ad libitum access to grain and water. Management of the pasture-based extended dam-rearing and the commercial group is presented in Ospina Rios et al. (2023).

Hot-iron disbudding was performed on the calves at 6 weeks of age (mean ± s.d., 6.53 ± 0.53 weeks) by a veterinary surgeon. Calves were disbudded over two-time replicates across 4 days. On Day 1, half of the commercial calves were disbudded, followed by half of the dam-reared calves on Day 2. On Day 3, the remaining half of the commercial calves underwent disbudding, and on Day 4, the remaining dam-reared calves were disbudded. The calves underwent a 12-h fasting period prior to disbudding to reduce the risk of perioperative complications. The morning of the disbudding (~8:00 AM), replicate calves were sedated with xylazine hydrochloride while in their home pen (0.05 mg/kg, intramuscular). Sedated calves had their horn buds clipped and a local anaesthesia (lignocaine hydrochloride 2%, 2 mL per each horn bud, subcutaneous) was applied at the bud base. Calves were then disbudded with a hot-iron (144G Express Pistol Grip Dehorner/debudder, Express Farming Croissy-Beaubourg, France) and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (meloxicam, 1.5 mg/kg, subcutaneous) was administered. After disbudding, dam-reared calves were monitored in the calf pen until they woke up (~1.5 h later), then walked to the paddock to re-join their dams, ensuring proper suckling. Commercial calves were monitored in their home pen until they woke up (~1.5 h later) and remained with their group peers. Once mobile, carers ensured they could suckle from the robotic feeders.

The attention bias test

Six hours post-disbudding (a time point when the effects of the drugs would likely have worn off (Neave et al. 2013), meaning that the calves would be experiencing pain during the ABT), calves dehorned on that day were separated from their dam or group peers and transported in a mesh-walled box trailer (1.5 m in width × 3 m in length × 1.7 m in height) in groups of five to six calves at a time exclusively with others from their experimental group, to an indoor arena. The arena was closer to the commercial calf pen, but they were transported a similar distance as the dam-reared calves. Calves remained with their treatment peers in the arenas pre-test holding pen for 30 min to allow calves to settle. The methodology of the ABT for calves was adapted from the procedures described by Lee et al. (2018) and Monk et al. (2018), and is described below.

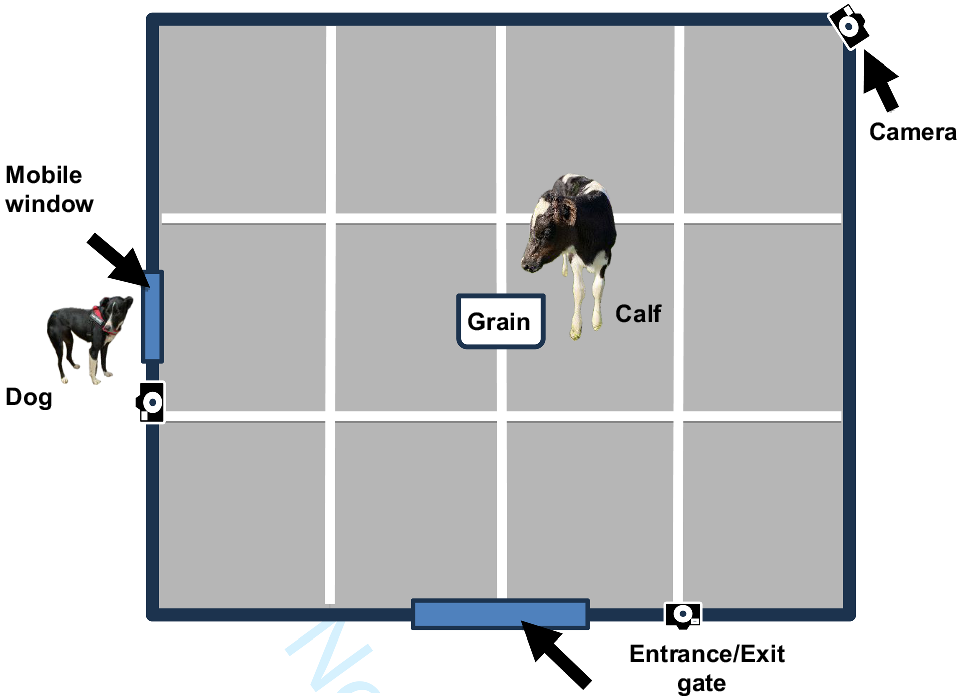

The ABT was conducted in an indoor arena purposely constructed for this project and contained within an enclosed shed. The test arena had a 4 × 5 m area with solid 1.5 m high wall to visually and physically isolate the calf, albeit enabling audio contact with the remaining calves in the group who were housed nearby. Grain concentrate (~2 kg), with which calves were already familiar because of its availability in the dam-reared and commercially reared calf pens from the beginning of the rearing period, was placed in a trough in the middle of the arena. The left side of the arena had a mobile window (80 × 60 cm) that opened to show a sitting dog. Three cameras (DJI Osmo Action) around the arena recorded the calves’ behavioural responses, and a 1.25 × 1.33 m grid was painted on the ground of the arena to divide the arena area into zones (see Fig. 1).

Schematic diagram of the attention bias test (ABT) arena adapted from Monk et al. (2018). A 4× 5 m arena, visually isolated from the environment by a 1.3 m wall, entrance/exit gate, a mobile window to provide dog exposition and three action cameras distributed around the arena. White lines represent a 1.25 × 1.33 m grid painted on the ground (not to scale).

Individual calves entered the arena and, once the arena door was closed, they were exposed to a quietly seated live dog (Border Collie) through the window for 10 s. The 10 s commenced once the calf had first sighted the dog. The window was then closed to visually remove the dog. The calf remained within the arena for a further 3 min, after which it was removed from the arena and returned to the holding pen with its peers. The test was terminated for any calf that showed high-severity fear behaviours (i.e. calf makes ≥4 attempts to escape the test arena or repeated and constant high-pitched calls). One calf from the dam-reared group attempted to escape the test arena more than four times, so was excluded from the analysis. On testing completion, the calves were collectively transported back to their treatment housing.

Behavioural response data for the calves was collected by a single trained observer using Behavioural Observation Research Interactive Software (BORIS, ver. 7.12.2, see https://github.com/olivierfriard/BORIS/releases/download/v7.12.2/boris-7.12.2-win64-setup.exe; Friard and Gamba 2016). An ethogram describing the behaviours observed from video recordings is presented in Table 1. Specific calf behaviours related to the dog (e.g. attention directed towards the dog, and approaches or withdrawals) that measured calf fear-related behavioural responses to the threat, were recorded during the 10 s when the dog was visible. The 3-min period when the dog was absent was intended to measure anxiety, reflecting the calf’s perception of the threat once it was no longer visible. However, the duration of time the calf was visually focused on the closed window was recorded for the first minute following the removal of the unfamiliar dog, following procedures previously used on Angus steers (Lee et al. 2018). All other behaviours were collected during the 3-min period immediately after the dog window was closed. Intra-observer reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa (κ), resulting in a coefficient of 0.90.

| Behaviour | Data recorded | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviours for the 10 s that dog is visible (fear-related behaviours) | |||

| Attention towards dog | Duration | The time the calf stands visually oriented towards the dog during the 10 s of exposure to the moment the calf moves her head in a different direction | |

| Calf approaches the dog | Frequency | The number of times that the calf takes one or more steps towards the dog while visually oriented to the dog | |

| Withdrawal from the dog | Frequency | The number of steps the calf takes away while visually oriented to the dog | |

| Behaviours for the 1 min following the window closing (anxiety-related behaviours) | |||

| Focus on dog window | Duration | The time the calf spends visually oriented towards the dog window once the window is closed | |

| Behaviours for the total 3 min following the window closing (anxiety-related behaviours) | |||

| Vigilance | Duration | The time the calf stands with her head positioned above the withers and ears erected, visually oriented to random places within the arena | |

| Locomotion | Frequency | The number of zones (grid painted) crossed by all four feet | |

| Exploration | Frequency | The number of times the calf is sniffing or touching the arena ground, walls or trough | |

| Latency to walk | Duration | The time for the calf to move at least a foot and place it a minimum of 20 cm away from the initial place | |

| Latency to eat | Duration | The time to the first collection or chewing of the food from the trough | |

| Standing | Duration | The time in which the calf stands with all four feet on the ground, with no movement reaction. The calf stand immobile, with no head movement | |

| Escape attempt | Frequency | The number of times the calf makes attempts to escape the test arena (i.e. jumping walls) | |

| Vocalisations | Frequency | The number of times the calf produces calls | |

| Elimination | Frequency | The number of times the calf urinates or defecates during the test | |

| Eating frequency | Frequency | The number of times the calf actively eats grain | |

Duration refers to time spent performing the behaviour and frequency to a count of the number of observed behavioural events. Adapted from Lee et al. (2018) and Monk et al. (2018).

Statistical analyses

In total, 21 calves were included in the analysis (dam-reared, n = 11; commercial, n = 10).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (ver. 29.0.0.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Standing frequency, standing duration, eliminations frequency and escape-attempt frequency were rarely observed, and, so, were excluded from the analysis. Their means are reported in the Results section. The normal distribution of all other behaviour variables was visually assessed using histograms, Q–Q plots and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic. The frequency and duration of attention towards dog, focus on the dog window and vigilance were correlated (r ≥ 0.61, P < 0.01), and, therefore, only durations were used in the analysis. Duration of focus on the dog window, latency to walk and duration in vigilance underwent logarithm + 1 transformation before analysis. Means and standard deviations are reported for descriptive data. Significant differences were established at P ≤ 0.05.

The effect of rearing treatment (dam-reared vs commercially reared) on the behaviour of calves in the ABT was analysed using linear mixed models (LMM). Rearing treatment was included in the model as a fixed factor, and day fitted as a random effect. Attention towards the dog (s), dog-window focus (s), exploration frequency, latency to walk (s) and vigilance (s) were analysed using LMM. Calf approaches the dog (number of events), steps withdrawn from the dog frequency, locomotion frequency, eating frequency, and vocalisations frequency were analysed using generalised linear mixed models (GLMM) with a Poisson distribution and log-link function, whereas calf approaches dog frequency GLMM used a Poisson distribution with identity link function.

Latency to eat grain was analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with rearing type (commercial or dam-reared) as a fixed effect. The analysis incorporated survival data, with calves that did not eat grain during the ABT being considered censored. In this model, commercially reared calves serve as the referent group. A hazard ratio greater than 1 indicates a higher likelihood of eating grain in the dam-reared group, and values between 0 and 1 indicate a lower likelihood, relative to the commercially reared calves.

Results

Dam-reared calves ate grain less frequently than did commercial calves in the 3 min after the window exposing the dog was closed (F1,19 = 8.10, P = 0.01). There were no significant differences for the attention-related behaviours vigilance (F1,19 = 0.101, P = 0.75) and attention towards dog (F1,2 = 0.002, P = 0.97). No other significant differences were found between the groups (see Table 2 and Supplementary material Table S1).

| Variable | Rearing treatment | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | Dam-reared | 95% CI | ||||

| Commercial | Dam-reared | |||||

| Fear-related behaviours (dog present) | ||||||

| Attention towards dog – duration | 7.1 ± 1.03 | 7.0 ± 1.00 | 2.7−11.5 | 2.3−11.8 | 0.97 | |

| Calf approaches the dog – frequency | 0.2 ± 0.22 | 0.1 ± 0.20 | −0.2 to 0.7 | −0.4 to 0.5 | 0.62 | |

| Withdraw from the dog – frequency | 0.4 ± 0.21 | 0.7 ± 0.25 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.49 | |

| Anxiety-related behaviours (dog absent) | ||||||

| Dog window focus – durationA | 1.0 ± 0.13 | 1.0 ± 0.12 | 0.7–1.3 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.86 | |

| Exploration – frequency | 10.6 ± 3.34 | 13.8 ± 3.27 | −3.8 to 25.0 | −1.4 to 29.0 | 0.57 | |

| Escape attempts – frequency | Not analysedB | |||||

| Elimination – frequency | Not analysedB | |||||

| Latency to walk – durationA | 1.1 ± 0.13 | 1.0 ± 0.13 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.60 | |

| Locomotion – frequency | 19.8 ± 6.94 | 15.3 ± 5.36 | 9.5–41.2 | 7.4–31.9 | 0.61 | |

| Eating – frequency | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 0.2 ± 0.13 | 0.9–3.7 | 0.0–0.9 | 0.01 | |

| Vigilance – durationA | 1.5 ± 0.14 | 1.6 ± 0.13 | 1.3–1.8 | 1.3–1.9 | 0.75 | |

| Vocalisations – frequency | 7.2 ± 3.22 | 5.5 ± 2.50 | 2.8–18.4 | 2.2–14.2 | 0.68 | |

Frequency variables represent the observed number of events and duration (s) of the observed total time. LSM ± s.e. with 95% confidence intervals are presented. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are presented in bold.

Overall, 76.2% (n = 16) of the calves did not eat grain, whereas 23.8% (n = 5) of the calves did and four of these were commercial calves. The mean latency to eat for the commercial calves that ate grain was 77.3 ± 58.05 s and for the dam-reared calf was 76.3 s. According to the Cox proportional hazard model, there were no significant differences in the likelihood of eating the grain during ABT between the groups (hazard ratio: 0.205 [95% CI: 0.023–1.836], P = 0.17).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of pasture-based dam-rearing on the behavioural responses of dairy calves in an ABT after undergoing disbudding. The key behavioural indicators associated with negative affect in an ABT are increased attention directed towards an area where a threat had been, increased vigilance and increased latency to consume feed after the threat is removed. We did not observe an effect of dam versus commercial rearing treatment on any of these measures in the calves. There was a rearing effect on the frequency of eating, with dam-reared calves eating less frequently. However, given the overall low proportion of calves eating and evidence that free-suckling calves consume almost no concentrate before weaning, even when compared with calves on high milk allowance (Fröberg et al. 2011; Ospina Rios et al. 2023), these results should be interpreted with caution. These results may suggest potential differences in the calves’ behavioural responses to ABT owing to their rearing treatment and painful disbudding, but this requires further investigation.

Except for eating grain, dam rearing did not affect the overall behavioural response of disbudded calves in the ABT, as assessed using the behaviours listed in the ethogram. This contrasts with findings in other species. For example, Winslow et al. (2003) found that 36-month-old mother-reared rhesus macaques were able to use a companion for social buffering in a novel environment test, but nursery-reared macaques were not. Similar results have been also reported in humans (Hostinar et al. 2015). It is possible that benefits of dam-rearing do not manifest in changes in calf behaviour during an ABT after disbudding, or the ABT may not have been sensitive enough to capture subtle differences in anxiety or pain perception between groups. However, there are differences in how the present research was designed, compared with previous studies, which warrant discussion. First, in the studies of Winslow et al. (2003) and Hostinar et al. (2015), testing occurred when subjects were out of the juvenile phase of the development. By contrast, the calves in this study were young at time of the testing. Conducting the ABT after a longer period of dam-rearing may yield different results. Second, previous studies demonstrated social buffering in animals that were in the presence of a companion, but the calves in this study were isolated during the ABT. Research on domestic hens (Edgar et al. 2015) and fish (Culbert et al. 2019) found evidence of social buffering when animals were faced with a stressor in the presence of their mother or social grouping, compared with in isolation. In guinea pigs, the presence of the dam during a novel environment test had a greater effect on reducing cortisol concentrations in the offspring than did the presence of an unfamiliar adult female (Graves and Hennessy 2000). We suggested that future studies observe calves in the presence of their dam or peers to fully elucidate the effect of social buffering on pain perception post-disbudding.

It is also possible that the design and conditions of the test arena used in this study affected calf behaviour. The behavioural responses of calves in the ABT presumably reflected their emotional states at the time of testing (6 h post-disbudding), when the calves were experiencing pain. The effects of sedation (Stafford et al. 2003), anaesthesia (Stafford and Mellor 2005) and pain relief (Heinrich et al. 2010) during disbudding are reported to gradually wear off over the next 6 h post-procedure. All calves were transported for the first time prior to the test, and this is known to be stressful. Indeed, cortisol concentrations peak within 30–60 min after loading calves for transport and decline over the next 2–6 h, and the highest cortisol response often occurs during shorter transport durations (reviewed by Eicher (2001)). In addition to pain and transportation, the dam-reared calves were experiencing separation from the dam and a fully enclosed indoor environment for the first time, complete with cement flooring. Thus, the results of this study may be reflecting the emotional state of calves to the additive effects of disbudding, separation from the dam, transportation, and a novel environment, rather than the effect of disbudding per se.

Willingness to eat is a validated indicator of anxiety in the ABT, but its validity requires all calves to consistently consume the food before testing. The trade-off between anxiety and willingness to feed has been seen in sheep (Lee et al. 2016), starlings (Brilot and Bateson 2012) and beef cattle (Lee et al. 2018). Whereas dam-reared calves were not consuming grain at 6 weeks, commercial calves consumed an average of 40 g/day, although 5 of 10 were not eating grain at all (Ospina Rios et al. 2023), and none had prior experience eating from a bucket. Notably, no differences were found in vigilance or attention towards the threat, key indicators in attentional-orienting assessments (Bethell et al. 2012; Brilot and Bateson 2012; Lee et al. 2016). Given that only a few animals ate the grain at all (4 of 10 commercial calves, 1 of 11 dam-reared calves), and the absence of vigilance differences, we recommend caution in interpreting grain consumption as an anxiety indicator in this study. To improve validity, the best approach would be to ensure that all animals have equal experience with the selected food before the ABT. One potential design could involve a ‘food familiarity phase’ where both groups are introduced to a highly palatable food item (e.g. hay, apples, carrots) outside their regular diet. This approach would ensure consistent exposure across groups and confirm that all calves are comfortable consuming the food before testing. A pilot study with non-experimental calves could further confirm intake levels under novel conditions. By prioritising equal experience with the food, these steps would enhance the reliability of feeding behaviour as an indicator of emotional state in future ABTs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the behaviour of young calves in an ABT. Lee et al. (2018) found that a dog visible for only 10 s was threatening to cattle. Animals treated with an anxiogenic drug showed increased attention towards where the dog had been, increased vigilance and had a greater core temperature than did cattle treated with an anxiolytic or saline. Future studies incorporating physiological measures, such as stress-induced hyperthermia, could further validate the distinction between neophobia and threat perception in this context. The cattle in Lee et al. (2018) also spent 6.7 of 10 s focused on the dog while visible, which is similar to the 7.2 s the calves from both treatments spent in this study. Thus, our results suggest that it is likely that calves in this study perceived the dog as a potential threat, as evidenced by their reduced exploration, increased vigilance, and alignment with previous findings on fear responses.

Behavioural variability in pasture-based systems may be underestimated when using power analyses based on indoor data. Variability in observed behaviours highlights the influence of individual factors, such as temperament and prior experiences in determining behavioural responses to challenging situations (Bushby et al. 2018). This variability could suggests that power analyses based on indoor systems may fail to account for the broader behavioural diversity influenced by the external environment in pasture-based systems. Research from indoor dairy systems reports positive effects of cow–calf rearing systems on calf growth, play behaviour, social behaviour and stress resilience when using 10–14 calves per treatment (Roth et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2015; Wagner et al. 2015; Santo et al. 2020; Waiblinger et al. 2020). Chen et al. (2015) found significant differences in serum cortisol concentrations and behaviour during a novel object behaviour test between mother-reared and artificially reared calves (n = 5 per treatment). The higher (P < 0.05) duration of staying near to a novel object (s) on mother-reared calves when than on artificially reared calves (682.5 ± 258.5 and 192.8 ± 112.9 respectively) could be detected with four animals in each group at 95% power. Therefore, we proceeded with a sample size of 10 and 11 calves per treatment in this analysis of calf behaviour in an ABT. Recognising the increased variability in pasture-based environments is essential for refining future sample-size calculations and ensuring robust behavioural assessments in outdoor systems.

Study limitations

This is the first study to assess emotional states in pasture-based dairy systems. Several factors are likely to have influenced the testing outcomes and should be considered when interpreting the results. We aimed to assess the ABT response of disbudded calved reared either with the dam or conventionally. Latency of calves to eat in the ABT may have been affected by treatment differences in familiarity with the grain, as commercial calves consumed more grain pre-test than did dam-reared calves. Additionally, conventionally reared calves were also more accustomed to cement flooring and indoor housing than were dam-reared calves. These limiting factors are directly associated with the rearing treatments imposed (dam-reared outdoors versus commercially reared indoors). The study sample size was determined using a power analysis and data derived from other species and indoor-housing systems; however, our results suggest increased variability potentially owing to pastoral rearing systems. Larger sample sizes are needed to determine the true effects of dam-rearing on calf affect post-disbudding specifically, and potentially for pasture-based behaviour studies generally.

Conclusions

Under the conditions of this study, dam-rearing did not alter behavioural responses indicative of anxiety in an ABT. The effect of the dam-rearing on pain perception may have been confounded by separation from the dam, a novel environment and transportation stress. This study has highlighted complexities in measuring affective states of dam-reared calves in an ABT. Development of a method to test calf affective states without removing them from their rearing environment will help elucidate the emotional experiences of calves in a pasture-based dam-rearing system.

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by the Australian Sustainable Agriculture Scholarship program and the RSPCA HughWirth Humane Animal Production Scholarship. The funders did not participate in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the paper, or the decision to publish the findings.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S. L. Ospina-Rios, C. Lee, S. J. Andrewartha and M. Verdon; methodology, S. L. Ospina-Rios, C. Lee, S. J. Andrewartha and M. Verdon; funding acquisition, M. Verdon; investigation, S. L. Ospina-Rios and M. Verdon; project administration, M. Verdon; resources, M. Verdon and S. L. Ospina-Rios; data curation, S. L. Ospina-Rios; formal analysis, S. L. Ospina-Rios and M. Verdon; visualisation, S. L. Ospina-Rios; writing – original draft, S. L. Ospina-Rios; writing – review and editing, S. L. Ospina-Rios, C. Lee, S. J. Andrewartha and M. Verdon; supervision, C. Lee, S. J. Andrewartha and M. Verdon. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude for the funding provided by the Australian Sustainable Agriculture Scholarship program (a joint UTAS-CSIRO) and for the valuable intellectual contributions of Thomas Snare in designing this system. We also extend our thanks to Carlton Gee, Steven Emmett, Desmond McLaren, Bradley Millhouse, Oliver Radford, Lesley Irvine, Nathan Bakker, Zelda the dog, Benjamin Noble, Steven Boon, Laura Field, Rowan Snare, and Peter Raedts from the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture (TIA), and Jim Lea from CSIRO for their assistance. We sincerely appreciate the reviewers’ valuable feedback, which has enhanced the clarity, analysis, and overall quality of our paper.

References

Beaver A, Meagher RK, von Keyserlingk MAG, Weary DM (2019) Invited review: a systematic review of the effects of early separation on dairy cow and calf health. Journal of Dairy Science 102, 5784-5810.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bethell EJ, Holmes A, MacLarnon A, Semple S (2012) Evidence that emotion mediates social attention in rhesus macaques. PLoS ONE 7, e44387.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brilot BO, Bateson M (2012) Water bathing alters threat perception in starlings. Biology Letters 8, 379-381.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bučková K, Moravcsíková Á, Šárová R, Rajmon R, Špinka M (2022) Indication of social buffering in disbudded calves. Scientific Reports 12, 13348.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bushby EV, Friel M, Goold C, Gray H, Smith L, Collins LM (2018) Factors influencing individual variation in farm animal cognition and how to account for these statistically. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 5 193.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chen S, Tanaka S, Ogura S-I, Roh S, Sato S (2015) Effect of suckling systems on serum oxytocin and cortisol concentrations and behavior to a novel object in beef calves. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 28, 1662-1668.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Costa JHC, Cantor MC, Adderley NA, Neave HW (2019) Key animal welfare issues in commercially raised dairy calves: social environment, nutrition, and painful procedures. Canadian Journal of Animal Science 99, 649-660.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Culbert BM, Gilmour KM, Balshine S (2019) Social buffering of stress in a group-living fish. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286, 20191626.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Daros RR, Costa JHC, von Keyserlingk MAG, Hötzel MJ, Weary DM (2014) Separation from the dam causes negative judgement bias in dairy calves. PLoS ONE 9, e98429.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ede T, Lecorps B, von Keyserlingk MAG, Weary DM (2019) Calf aversion to hot-iron disbudding. Scientific Reports 9, 5344.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Edgar J, Held S, Paul E, Pettersson I, I’Anson Price R, Nicol C (2015) Social buffering in a bird. Animal Behaviour 105, 11-19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Eicher SD (2001) Transportation of cattle in the dairy industry: current research and future directions. Journal of Dairy Science 84, E19-E23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Faulkner PM, Weary DM (2000) Reducing pain after dehorning in dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science 83, 2037-2041.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Flower FC, Weary DM (2003) The effects of early separation on the dairy cow and calf. Animal Welfare 12, 339-348.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Friard O, Gamba M (2016) BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7(11), 1325-1330.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fröberg S, Lidfors L, Svennersten-Sjaunja K, Olsson I (2011) Performance of free suckling dairy calves in an automatic milking system and their behaviour at weaning. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A – Animal Science 61, 145-156.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Godden S (2008) Colostrum management for dairy calves. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 24, 19-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Graves FC, Hennessy MB (2000) Comparison of the effects of the mother and an unfamiliar adult female on cortisol and behavioral responses of pre- and postweaning guinea pigs. Developmental Psychobiology 36, 91-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Heinrich A, Duffield TF, Lissemore KD, Millman ST (2010) The effect of meloxicam on behavior and pain sensitivity of dairy calves following cautery dehorning with a local anesthetic. Journal of Dairy Science 93, 2450-2457.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hennessy MB, Kaiser S, Sachser N (2009) Social buffering of the stress response: diversity, mechanisms, and functions. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 30, 470-482.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hostinar CE, Johnson AE, Gunnar MR (2015) Early social deprivation and the social buffering of cortisol stress responses in late childhood: an experimental study. Developmental Psychology 51, 1597-1608.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Huber J, Arnholdt T, Möstl E, Gelfert CC, Drillich M (2013) Pain management with flunixin meglumine at dehorning of calves. Journal of Dairy Science 96, 132-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kiyokawa Y, Hennessy MB (2018) Comparative studies of social buffering: a consideration of approaches, terminology, and pitfalls. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 86, 131-141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lee C, Verbeek E, Doyle R, Bateson M (2016) Attention bias to threat indicates anxiety differences in sheep. Biology Letters 12, 20150977.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lee C, Cafe LM, Robinson SL, Doyle RE, Lea JM, Small AH, Colditz IG (2018) Anxiety influences attention bias but not flight speed and crush score in beef cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 205, 210-215.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McMeekan C, Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ, Bruce RA, Ward RN, Gregory NG (1999) Effects of a local anaesthetic and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic on the behavioural responses of calves to dehorning. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 47, 92-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Meagher RK, Beaver A, Weary DM, von Keyserlingk MAG (2019) Invited review: a systematic review of the effects of prolonged cow–calf contact on behavior, welfare, and productivity. Journal of Dairy Science 102, 5765-5783.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mintline EM, Stewart M, Rogers AR, Cox NR, Verkerk GA, Stookey JM, Webster JR, Tucker CB (2013) Play behavior as an indicator of animal welfare: disbudding in dairy calves. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 144, 22-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Monk JE, Doyle RE, Colditz IG, Belson S, Cronin GM, Lee C (2018) Towards a more practical attention bias test to assess affective state in sheep. PLoS ONE 13, e0190404.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Monk JE, Campbell DLM, Lee C (2023) Future application of an attention bias test to assess affective states in sheep. Animal Production Science 63, 523-534.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Neave HW, Daros RR, Costa JHC, von Keyserlingk MA, Weary DM (2013) Pain and pessimism: dairy calves exhibit negative judgement bias following hot-iron disbudding. PLoS ONE 8, e80556.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ospina Rios SL, Lee C, Andrewartha SJ, Verdon M (2023) A pilot study on the feasibility of an extended suckling system for pasture-based dairies. Animals 13, 2571.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Roth BA, Barth K, Gygax L, Hillmann E (2009) Influence of artificial vs. mother-bonded rearing on sucking behaviour, health and weight gain in calves. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 119, 143-150.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Santo NK, König von Borstel U, Sirovnik J (2020) The influence of maternal contact on activity, emotionality and social competence in young dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Research 87, 138-143.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ (2005) Dehorning and disbudding distress and its alleviation in calves. The Veterinary Journal 169, 337-349.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ (2011) Addressing the pain associated with disbudding and dehorning in cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 135, 226-231.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ, Todd SE, Ward RN, McMeekan CM (2003) The effect of different combinations of lignocaine, ketoprofen, xylazine and tolazoline on the acute cortisol response to dehorning in calves. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 51, 219-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wagner K, Seitner D, Barth K, Palme R, Futschik A, Waiblinger S (2015) Effects of mother versus artificial rearing during the first 12 weeks of life on challenge responses of dairy cows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 164, 1-11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Waiblinger S, Wagner K, Hillmann E, Barth K (2020) Play and social behaviour of calves with or without access to their dam and other cows. Journal of Dairy Research 87, 144-147.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Winslow JT, Noble PL, Lyons CK, Sterk SM, Insel TR (2003) Rearing effects on cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin concentration and social buffering in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 910-918.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |