A Merningar Bardok family’s Noongar oral history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and surrounds

Lynette Knapp A , Dion Cummings A , Shandell Cummings A , Peggy L. Fiedler B and Stephen D. Hopper C *

C *

A

B

C

Abstract

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this document may contain sensitive information, images or names of people who have since passed away.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on Western Australia’s south coast is world renowned for its biodiversity, particularly its threatened fauna. Future co-management of the Reserve with Aboriginal peoples is likely, although very little information on the Noongar cultural heritage of the Reserve has been published and thus available for stewardship guidance.

This study used oral history interviews on Country based on open-ended questioning and respect for intellectual property. Comprehensive surveys for Noongar cultural heritage were conducted on foot on the Reserve.

A rich trove of women’s and men’s stories from the Knapp family about Two Peoples Bay is recalled and recorded. The Reserve features prominently in Wiernyert/Dreaming stories with classical human moral dilemmas, and transformations for wrong-doing are featured. Threatened animals and important plants are named as borongur/totems. Trading of gidj/spears of Taxandria juniperina is prominent. Use of fire traditionally was circumspect, and is confined to small areas and pathways in lowlands. Granite rocks are replete with lizard traps, standing stones, and stone arrangements.

The Reserve has a long and layered oral history for Merningar Bardok Noongars, exemplified here by the Knapp family, members of which have enjoyed continuous oral history for countless generations. Granite rocks, wetlands, flora, and fauna are vitally important vessels of such knowledge.

Cultural suppression has inhibited free cross-cultural exchange of kaatidjin/knowledge until recently. As respect for culture and Elders becomes paramount, positive co-stewardship of the Reserve will become a reality. Vibrant cultural interpretation and active management by Noongar guides and rangers is recommended.

Keywords: borongur, continuous oral history, dreaming, elders, family-based cross-cultural research, granite rocks, lizard traps, OCBIL, spears, stone arrangements, totems.

Our paper begins this Special Issue on The Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve to provide context for the information presented herein, and so doing, we honour and respect Noongars, the Aboriginal peoples of southwest Australia. Of particular importance is that the Knapp Family, ancestors and custodians of Country – past, present, and future, have contributed generously both as authors and informants. Stewardship of Country was focused at the family level in Noongar culture, not by higher political units such as ‘tribes’ or nation-states. Noongar vocabulary is written along with the English translation as ‘Noongar/English’ to assist in cross-cultural understanding.

We begin with a précis of the ethnography of the Two Peoples Bay landscape (Fig. 1), and then progress to a discussion of significant cultural features, such as landscapes associated with the Wiernyert/Dreamtime, lizard traps, and granite rock stone arrangements. This examination concludes with a 16-part conversation illustrating the remarkable legacy of Merningar Bardok oral history. The conversation is the verbatim transcription about Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve between Steve Hopper, one of the authors and extant members of the Knapp Family: Lynette Knapp, Dion Cummings, and Shandell Cummings. This respectful and engaging exchange reveals the rich knowledge and landscape stewardship practices of the Merningar Bardok, and bears testimony to the cultural richness of Noongar lifeways across the south coast of Western Australia.

Google Earth image of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (red boundary) and adjacent lands giving Merningar place names and spellings developed at an Elder-led workshop in January 2024. Inset map shows context of Two Peoples Bay and some places mentioned in the text in the Southwest Australian Floristic Region, Provinces and Districts (base map from Gioia and Hopper 2017). Camelot farm near the southwest boundary of the Reserve is where the Knapp/Cummings family lived and worked from 1982 to 1986, within a few kilometres of the traditional Knapp family camp below the Tyuirtyallup sand dunes.

Introduction

Scant attention has been paid to Aboriginal peoples and their care of Country in previous papers or anthologies of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (TPBNR), even as recently as the 30+ year old draft of this special issue. The original ethnographic narrative – the discussion of cultural history and land stewardship – began in 1791, with Vancouver’s charting of the southwestern coast and naming of Mt Gardner. It represents an oversight of Aboriginal land tenure not uncommon even a few decades ago.

The Two Peoples Bay area was under active management for tens of thousands of years by Noongar people. Management was by family groups who operated under a set of lores that evolved over tens of thousands of years. These lores were handed down through generations by way of narratives passed down by Elders to those initiated to receive the knowledge and put it into practice. By the time Vancouver arrived, TPBNR was a cultural and social landscape cared for by a small group of families to provide an environment in which people could live in perpetuity and be able to pass on the same options for future generations that the current inhabitants enjoyed. Passing knowledge down through narratives/stories, the physical elements of the landscape were critical as they stood over time as landmarks to the consequences of not following lore; e.g. the story below of the star-crossed lovers and reminders in the landscape of departing from lore governing relationships.

A proper ethnographic chapter originates in the Wiernyert/Dreaming – a time far earlier than the European occupation of TPBNR. Yet a comprehensive treatment of the lives, beliefs, and ways of Noongar land stewardship at Two Peoples Bay is beyond the scope of our paper. What we offer in the remaining text is an ethnographic précis, an illustration of cultural features of the Two Peoples Bay landscape, and an engaging cross-cultural conversation among trusted friends about caring for Country.

The ethnographic record for traditional Noongar life in southwest Australia is rich for some places and Aboriginal groups, but it is strongly biased towards male interpretations and perspectives. Regardless, there are rewards in reading accounts of traditional Noongar life, e.g. in Perth by Moore (1884), and Hallam (1975), and, in Albany by Barker (1830), Nind (1831), and Collie (1832), among others. Dictionaries and collated vocabularies also deliver insights for specific places, including those written by Rooney (2011) for New Norcia and by Bussell (n.d.) and Webb (n.d.) for the Margaret River. Other examples can be found from across the southwest (von Brandenstein 1988), and across Australia (Pascoe 2014). Among the most familiar is the extensive, largely unpublished archive of Daisy Bates, who explored genealogies and broader stories across campsites from the early 1900s (Thieberger 2017). We recall several of her insights about Noongar ethnography in the following text.

An important consideration in pursuing enquiries about traditional life, however, is the recognition that so much is specific and place-based, with interpretations hinging on the extended family unit and its domain (e.g. Mokare’s domain; Ferguson 1987) rather than ‘tribes’ or nation-states. Often, early ethnographers did not attribute information obtained to specific individuals or families and tended to generalise for the Perth and Albany regions, as well as for other communities. This tendency ultimately disengaged the central importance and agency of individuals from their families, causing significant personal harm and loss of continuous oral history (Haebich 1992).

Herein, we draw attention to the need to attribute information to specific families and specific places. As we will demonstrate, there is a tremendous depth and breadth of intimate, place-based knowledge still held by some living Noongar families that is largely unrevealed to the wider public, for cogent reasons. Generations enduring the consequences of white cultural suppression keenly feel the need to hold their family information close as the single unbroken link to traditional culture central to their sense of identity and well-being. Moreover, those relatively few Noongar families that escaped the stolen generations1 (Haebich 1992) have a remarkably rich archive of continuous oral history upon which to draw.

Ethnography of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (the Reserve) and the surrounding landscape have a lean body of published ethnographical information, despite a rich trove of Noongar cultural practices overall. A comprehensive literature mostly begins around 1840, according to Daisy Bates, the Irish-born ethnographer and journalist renowned for her meticulous anthropological field work in western and southern Australia. Although Bates left an extensive set of notes and manuscripts (Thieberger 2017), we relate those most relevant to the history of the Reserve.

Bates interviewed a man, Nebinyan born near Albany at Oyster Harbour’s Katta burnup/Mt Martin around 1840 (Gibbs 2003). His genealogy and vocabulary recorded by Bates highlight a life spent associated with the whaling industry (Fig. 2). Hired in 1862 as a boat hand with the nydiyang/white settlers, he told his powerful stories of 15 years of whaling in song, which attracted the attention of workers including Gibbs (2003), as well as contemporary Noongar scholars and musicians such as Clint Bracknell (2017). Indeed, Noongars like Nebinyan were recruited by the whaling companies onto their crews and were rewarded equally to Europeans for their efforts (Gibbs 2003). Regrettably, Bates did not record the words of Nebinyan’s repertoire, but instead, gave a brief, melancholic account of his campfire renditions at Katanning in 1907 (Bates 1985; Gibbs 2003).

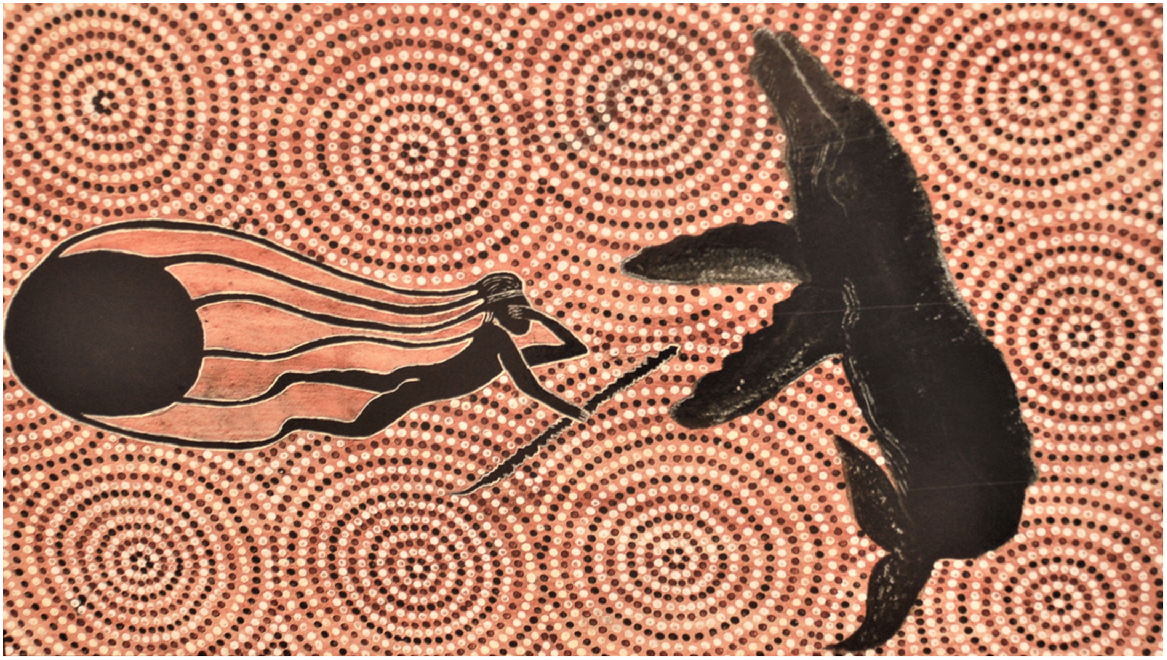

Nebinyan artwork by Shandell Cummings commissioned for the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve Visitor Centre. Nebinyan’s Wiernyert/Dreaming streams from his head and it is much to do with whales and whaling. Photo S. D. Hopper.

In 1837, a seasonal whaling station was established at Two Peoples Bay (Chatfield and Saunders 2024), lasting for a few years but resurrected briefly in 1873. Whaling is believed to be the European industry least disruptive to Noongar lives, compared with pastoralism and farming (Gibbs 2003). Indeed, it may have been celebrated by the Noongars, given that whale strandings provided occasional gathering points for ceremonies and week-long meat consumption from time immemorial. Because European whalers sought only baleen and oil, whale carcasses were left to the Noongars and thus used in a traditional manner. Nebinyan’s prowess afforded an opportunity to command respect as a relatively young Noongar man. This development inevitably came at a time of dramatic change to traditional lifeways, as the transition to the dominance of European settler society must have been a cause of great concern to traditional Elders. Unfortunately, the written record of the Noongar custodians of Two Peoples Bay is silent on this matter.

Bates recorded that Nebinyan’s father was Burduwan/‘maker of the burdon’ from Yilbering/Two Peoples Bay (Thieberger 2017), and his borongur/totems were wordung/raven (Corvus coronoides) and merderung/sea mullet (Mugil cephalus). His father was married to Nungilan, a woman from Yiilangarup/Yulingarup near Two Peoples Bay (Fig. 1). Her borongur/totems were manitch/white-tailed black cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) and ngwar/Western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis). Both parents were recorded as ‘Minang speakers’ by Bates, which is somewhat confusing, although ‘Minang’ may be an abbreviation of Merningar, meaning ‘whale people.’ Alternatively, ‘those who eat mean’ (Haemodorum spicatum) was suggested by Nind (1831). Bates’ genealogy for Nebinyan mentions that Nebinyan’s father(s) were skilled in spear construction, particularly burdon/‘heavy war spears’ (Thieberger 2017). This is an important early reference to spears and spear-making as being a special cultural focus of the Noongars of Two Peoples Bay.

Nebinyan had two consorts, only one of whom is well documented: Nguranit from Takilarap/Lake Andrew north of the Stirling Range, and Ngurakoyt, whose brothers Talarit and Tutinwer had identical places of birth and totems to Nebinyan. Two children were born from Ngurakoyt and Nebinyan’s marriage, a boy, Karalit, who inherited his father’s totems; and a girl, Kaneran, whose borongur/totems were manitch/white-tailed black cockatoo and ngamalar/chestnut-breasted shelduck (Tadorna tadornoides).

Thus, the small amount of information on Two Peoples Bay lifeways that can be gleaned from Nebinyan’s genealogy relate to spear-making, a few culturally important animals, and the sheoak tree (Allocasuarina huegeliana). Even Bates, in her two most prominent publications, cited Two Peoples Bay only in passing mention of Nebinyan’s death in 1907 (Bates 1992 but given as 1910 in Thieberger 2017) and in quoting a brief description of his whaling song (Bates 1985).

Bates wrote more about another Elder, Wandinyilmirnong, also known as Tommy King, whom she stated was born in Kinjilyilling/Albany, but who may actually have come from Two Peoples Bay (Knapp unpublished family history). Wandinyilmirnong was Lynette Knapp’s great uncle. His genealogy as recorded by Bates gives his borongur/totems as ‘Gidj (didar)’ and ‘Ngilgaitch (like a bandicoot)’. The latter most likely is Gilbert’s Potoroo (Potorous gilbertii).

An introduction to the Merningar Bardok Knapp family

Lynette Knapp (LK, b. 19 July 1954), her daughter Shandell Cummings (SC, b. 8 March 1971), and son Dion Cummings (DC, b. 30 September 1978) belong to the Knapp Family (Appendix 2 in Arnold 2015). All three were instructed by Alf Knapp (Fig. 3), Lynette’s father, who was born in Albany in 1914. Alf was a full Noongar language speaker who enjoyed continuous oral history from his father Johnny, mother Lilian Bevan/Annie Williams, and other Noongars. LK escaped long-term placement in Gnowangerup Mission because when taken there as a child, she immediately contracted meningitis. LK was given back to her father within 2 weeks of falling ill; she remained in hospital for several months and then was nursed back to health by Alf. When she could not sleep, LK was entertained by her father around the campfire with songs and stories from her family’s long history on the south coast.

Alf Knapp with one of his sisters Bonnie Knapp, whose words and stories primarily are reflected herein as memorised by LK, DC and SC over countless yarns on Merningar Bardok Country. Many other Elders from the Knapp family and others also contributed to this remarkable body of orally transmitted katidjin (knowledge). Photographers unknown.

As Merningar Bardok people, the Knapps ranged over 800 km from Israelite Bay to Denmark, 50 km west of Albany, and as far inland as extended the northern geographic limit of the blue mallee (Eucalyptus pleurocarpa), an important botanical marker of territory for Noongars (Oldfield 1865). The family travelled regularly along their maart/paths over this extensive region, applying fire where and when appropriate, i.e. principally on lowlands and travel paths in autumn (Lullfitz et al. 2021). They kept largely to themselves and at LK’s grandfather Johnny Knapp’s insistence, only drew water from nightwells, not from open pools. Nightwells are dry in daylight but fill with water after sunset. The family had well-remembered travel routes to take advantage of such watering points.

The group of people with whom they identify are Merningar/‘whale people’ Bardoks/‘people of rough stony Country who will spear you to death.’ Merningar regard themselves also as people of the white sand, and shell people. The Bardok Noongars were mentioned in a few historical accounts as rarely encountering nydiang/white people (Dempster 1865; Helms 1896; Hassell 1975). Their geographical range broadly correlated with the distribution of the Taalyeraak (blue mallee and E. extrica) eucalypts, whose combined geographic range extends from the edge of the Nullarbor cliffs northeast of Israelite Bay, west to the Stirling Range, and extending as far inland (north) as The Lake King–Norseman Road. However, we know from their family history that Johnny Knapp travelled as far north as Hyden Rock (360 km), and as far east as Knapp Rock, west of Lake Johnston (400 km). A railway siding 50 km north of Kalgoorlie was also named Bardoc, indicating some family communication well north into the Goldfields (Fig. 1). The Merningar Bardoks had a special affinity with white sand Country on the south coast, particularly associated with dunal blowouts known as Tyiurrt yaalap or Tyirnduyalaba.2

Apart from their fearsome reputation, the Bardoks were famous for some individuals being polydactylous, with six fingers and six toes on their limbs (Helms 1896; Hassell 1975). This genetic attribute is still evident today in the extended family. Such an unusual physical trait added to the Knapp family’s reputation as being enspirited people with six-toed footprints.

Because of their elusive and sometimes secretive nature, the Merningar Bardoks were not mapped by Tindale (1974) as a distinct dialect group of Noongars. Yet contemporary linguistic studies highlight several words and phrases that are uniquely Bardok (Knapp and Yorkshire 2022). Some have been incorporated into placenames, such as the Bardok word ‘yeel’ for hill rather than ‘kaat’ used by Menang people. Yilberup is the traditional name for Mt Manypeaks (Fig. 1), which means ‘the rough and rocky hill’ (Table 1). The word Noongar itself is a Bardok word for a warrior who has gone through two sets of law – desert and coastal (von Brandenstein 1988). Hence strictly speaking, women cannot be Noongar warriors. It seems ironic that ‘Noongar’ has been widely adopted in recent times as the name for the Nation that extends from Yued Country in the northwest to Bardok Country beyond Israelite Bay. LK says she is not a Noongar but a Bibbulmun, another Bardok word for the Nation also advocated for by Bates (1992). The Knapp’s Bardok language was written down by Bates when she interviewed Lynette’s great grandmother, Jakbam, with one of her husbands, Wobinyet, in the early 1900s (Thieberger 2017).

| Place name | Existing name | Derivation | Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyanbelokup | Rock Dunder | Boyan = orphan; belok = ankle | Boyankaatup’s ankle, where he tripped forward and turned into a shark after being hit in the back by the No. 7 boomerangA | |

| Boyankaatup | Hilltop south-west above Little Beach | Boyan = orphan; kaat = hill, head | Stone head of the orphan of the first of the Seven Sisters turned to stone | |

| Boyanup | Tidal pool | Boyan = orphan | Place of the orphans | |

| Djilliyiranup | North Point | Djilli = wing tip, yir = upturned, an = kept; | White-breasted Sea Eagle (Icthyophaga leucogaster) place, signifying men’s law ground | |

| Kaiupgidjukgidj | Moates Lagoon | Kaiup = water, gidj = spear, uk = for, on, to, gidj = spear | Lake with an abundance of gidj (Taxandria juniperina) for making spears | |

| Koortyill | Unnamed red hill adjacent Herring Bay at the north end of Two Peoples Bay | Koort = heart, yill = hill | Hill where Tandara placed her broken heart after seeing her baby die at the hand of Yilberup | |

| Maardjitup Gurlin | Mount Gardner | Maardjit = white-pointer shark; gurlin = movement, no. 7 kylie/boomerang | Place of Boyankaatup in the form of a white-pointer shark, moving, with the dorsal fin the No. 7 boomerang thrown by Yilberup | |

| Miialyiin | Angove lake | Miial = eyes; yinn = tears | Tears of Tandara grieving for her baby | |

| Naarup | Waterfall Bay | Naar = edge of cupped hand, edge of bay | Place for drinking freshwater with cupped hands by the ocean | |

| Nornarup | Nanarup | Norn = black snake; arup = become | Place where black snakes thrive | |

| Tyiurrtmiirity | Gardner Lake - Angove Lake wetlands | Tyiurrt = spirit man, ancestral being of the southern coast, sandy blondy; miirity = water snake | Giant spirit snake place | |

| Tyiurrtyaalup | Moates dunes | Tyiurrt = sandy spirit man, ancestral being of the southern coast, sandy, blondy; yaal = sand | Enspirited dunes where people camped to trade for spears, and where Boyankaatup stood throwing rocks north at Yilberup across Two Peoples Bay | |

| Yaalup | South Point | Yaal = sand, grave | Place of graves dug in sand | |

| Yiilangarup | Boulder Hill, Bettys Bay | Yiil = hill, an = kept, gar = people of | Place of the people of the hills | |

| Yilberup | Mount Manypeaks | Yiil = hill, bar = rough, stony | Rough hill of stones. Also place where the stars fell to the ground when the dark emu was flung up into the sky. Place of ancestral bordier/boss Djimaalap’s son. | |

| Waychinicup, Waichinicap | Waychinicup estuary, inlet | Waitch = emu; tyianaq = little foot, ghost, spirit; up = place of | Place where the Wiernyert/Dreamtime emu stepped when being chased by the black magic snake from Alice Springs to Albany, or river that puts Emus into being (von Brandenstein 1988 pg 150) |

The use of Tyiurrt is not without precedent, e.g. Tyiurrtgellong for Lake Seppings at Albany; Mt Chudalup = tyiurrtilup south of Northcliff. Similarly, Boyanup has been used for orphan place on the southern Swan Coastal Plain. Derivation and translations from Knapp family oral history, Jakbam’s vocabulary and Nebinyan’s geneology (von Brandenstein 1988; Thieberger 2017).

Merningar Bardok Tales of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve

Two short tales from the published Knapp family stories (Knapp 2011) illustrate that TPBNR is clearly part of traditional Merningar Bardok Country. First, Djimaalap is the ‘sad story of two young people from the same tribe who were madly in love with each other, and what happened to them when they disobeyed the Elders. Djimaalap and Yirdiyan were two young lovers who could never marry because it was forbidden’ (Knapp 2011, p. 3). When trying to elope with the help from Djimaalap’s friend, Boykaatap3 as a lookout, the young lovers were discovered by the Elders. Boyankaatup was turned into stone forever looking across the bay to Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks (Fig. 1). Yirdiyan was turned into a little bird, the Western gerygone (Gerygone fusca), which is the Knapp family’s animal borongur/totem. Djimaalup became the noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) (Fig. 4) forever calling out to his beloved Yirdiyan. This story is told in depth in the oral transcriptions later in the paper.

Country speaks at Little Beach, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. A prohibited elopement of Djimaalap and Yirdiyan sealed their fate as humans transformed into birds, with the orphan lookout Boyankaatup forever turned to stone looking north at Yilbarup/Mt Manypeaks. Landscape photos S. D. Hopper. Birds Graeme Chapman, Alan Danks. Other images from Knapp (2011).

A second story, Margit wer Barmba/shark and stingray, is a men’s tale about two brothers who fought over a young woman. One brother was good at throwing gidj/spears and the other, a kylie/boomerang. The Elders, tired of the brothers squabbling, sent them to The Gap in today’s Torndirrup National Park south of Albany. Each stood on one side of The Gap and together they threw their weapons at the other brother; each hit their mark. Falling into the water, the brother hit by the kylie/boomerang turned into a shark, and the other, a stingray. As will become evident below, this story is foundational to an understanding of the origins of TPBNR. Again, this tale is featured in the oral transcriptions.

Most activities of traditional everyday life, including the use of small-scale cool burning of camps and tracks, were conducted low in the landscape near beeliar/fresh water sources and good hunting and gathering grounds. For example, we feature for the first time in the transcripts below a form of aquaculture practised to foster the growth of edible freshwater mussels (Westralunio inbisi) in TPBNR.

Uplands, particularly granite rocks, were only for day use and usually special ceremonial occasions, with various access restrictions depending upon age and gender (Lullfitz et al. 2021; Cramp et al. 2022; Rodrigues et al. 2022). In many ways this perspective on differential land use developed by Noongars over thousands of generations is reflected in the independently derived theory of old, climatically buffered infertile landscapes (OCBILs; Hopper 2009, 2018, 2023). Once this overlap in world views was realised, strong collaboration developed between the Knapp family and conservation biologists based at The University of Western Australia’s (UWA) Albany campus and elsewhere, as recognised by Hopper and colleagues (2016, 2021; Hopper 2023), Lullfitz et al. (2017), Silveira et al. (2021), and exemplified in the present paper.

LK and the extended Knapp family have increasingly shared and celebrated their culture through various activities, including publications (Lullfitz et al. 2020, 2021, 2023a; Knapp and Yorkshire 2022) and modern electronic newsletters such as The Conversation (Lullfitz et al. 2023b). LK is now an Adjunct Elder/Research Associate with the University of Western Australia’s Albany campus and plays an active role in teaching and co-supervising advanced degree students working in conservation biology and ethnobiology (e.g. Cramp et al. 2022; Rodrigues et al. 2022).

Merningar Cultural Legacy at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve: lizard traps and stone arrangements on granites of the reserve

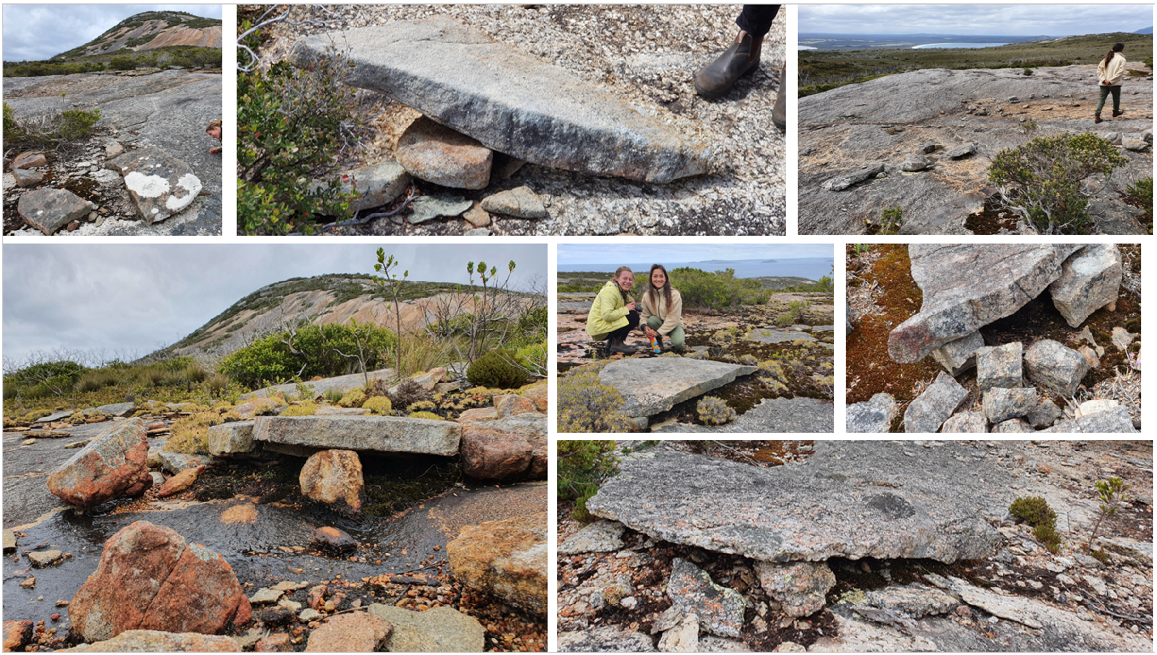

Not surprisingly, the oldest signs of ancestral practice on TPBNR and elsewhere are in the oldest parts of the landscape that persist for the longest time; the granite outcrops. Lizard traps, for example, are to be found everywhere vehicular access is difficult and is distant from nydiyang/white people’s trails (Cramp et al. 2022; Fig. 5). These simple rock constructions of a rock slab propped up (‘coverstones’) provided shelter and habitat for lizards and snakes, but also served to create lizard hunting sites for Noongars. Mining of these coverstones was widely practised using stone axes and fire to crack thin slabs orthogonally (Fig. 6). Other common stone structures erected by ancestors include standing stones, and stone arrangements (Fig. 7). Certain configurations of standing stones are known to be markers warning women and uninitiated children not to go further. The significance of other stone arrangements is sacred knowledge and not to be widely shared. Moreover, large stone structures such as the summit of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner often relate to Wiernyert/Dreaming or astral connections. In short, the entire eastern inselberg of the Reserve is replete with special cultural sites on granite.

Lizard traps are common on the upper slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. They consist of a flatrock averaging approximately 1 m square, held above the bed rock at one end by one or more propstones. This creates a dark space opposite the propstone which lizards and snakes retreat to when threatened. Susie Cramp and Larice Guislain in centre photo for scale. Photos S. D. Hopper.

Mine for lizard trap top slabs. A thin sheet of exfoliating granite is chosen to chip away orthogonal squares to which fire is applied along the joins (the orange colour of the rock indicates it has been burnt). This weakens the granite and enables slabs to be prised off the bedrock. Note the finer texture of the mined apalite, as distinct from the rougher-surfaced granite rock with bigger crystals adjacent. Cape Vancouver looking south-southwest, with Boyanbelokup/Rock Dunder in the midground and Breaksea Island on the horizon. Photo S. D. Hopper.

Various stone arrangements not due to natural causes that have been created by Noongars west and south of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner including: (a) Lizard trap adjacent a standing stone pointing to the summit; (b) another standing stone propped up atop a tor and pointing east past the summit; (c) standing stone; (d) complex quartz mine with lizard traps, standing stones and arranged small boulders; (e) lizard trap and circular stone arrangement; and (f) standing stone with face engraved at one end on seal-shape pointing to Boyanbelokup/Rock Dunder. Photos S. D. Hopper.

The bare dunes near Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon similarly is an entire landform of significance as it served as a major trading centre connected to the Wiernyert/Dreaming where Boyankaatup threw rocks at Yilberup (see transcripts below). Within the dunes are countless archaeological sites that are exposed then reburied as the sand shifts with the wind. A much more generous concept of Aboriginal ‘special site’ is needed if the full gamut of Noongar spirituality and daily life are to be respected.

Discussion

The remarkable body of Merningar Bardok oral history, as retold in the following text and published here for the first time, bears testimony to the cultural richness of Noongar lifeways across the south coast of Western Australia. Specifically, regarding TPBNR and environs, there is now a perceptive and insightful account of landscapes managed by Noongars for tens of thousands of years.

There is an elegance and rhythm to the stories revealed herein. They are and were spoken in plain language, and they are easily remembered; although some of their richness is lost in the written word. There is something moving and powerful witnessing their telling on Country that the associated video archive held by UWA highlights. Of course, much has been lost or cannot be told in this format; the songs, specific dances, secret rock art, and the special knowledge of people, plants, animals, and places. The stories were filtered by Alf Knapp and other Elders as recited to LK, DC, and SC, and they have been filtered again by the authors of this paper. Aspects of secret men’s and women’s business, and age-related controls over conveyed knowledge were and are managed carefully. Yet sufficient cultural heritage has been transmitted into the public domain here to enliven understanding of the cultural importance of the Reserve to all who live today and for the descendants of the Knapp family and others. Agency and respect have been restored to the Noongar intellectual property holders of the Knapp family as best as possible in this process.

Some of the layering of Noongar stories emerges from a reading of the Knapp family oral history. There are countless perspectives on each tale, depending upon who the storyteller is, who the receivers of the story are, and where in the landscape the storytellers and receivers are positioned. Yet central themes concerning the Wiernyert/Dreaming and creation of landscapes and lifeways emerge repeatedly.

Most stories of landscape and ancestral characters have a clear moral to them. Djimaalap and Yirdiyan disobeyed the Elders in trying to elope, so as punishment they were turned into birds (Fig. 4). Boyankaatup tried to help the planned elopement as a lookout and is forever now looking across at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks as punishment for the transgression of traditional law. Boyankaatup and Yilberup committed the cardinal sin of brothers fighting over their sister as a marriage partner and were turned into marine animals before being locked into stone after their great fight.

A legacy of the Knapp’s oral history is the potential to adopt Noongar place names within and adjacent to the Reserve. Fig. 1 was derived in a family workshop with suggestions that make sense in terms of many of the stories told herein (Table 1). Something would be lost in translation if these were adopted under the belief that there is only a single placename for each feature in Noongar culture. Every family has its own stories and they differ within and among families depending upon context and historical interpretation. It is important to remember this and appreciate the diversity as collective truths. We should not be worried by the lack of agreement on specific details nor language used. That is part of the richness of the culture, as are the general themes that emerge and provide the overarching superstructure to the layers of tales beneath.

Faunal persistence and the megafauna

The great biological success of TPBNR and surrounds has been the assisted persistence of endangered animals rendered extinct elsewhere across their original ranges. Noongars would argue that the persistence of animals such as the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and Nilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo is because they have continued to be celebrated through oral history right up to the present day. Their stories and key roles in Wiernyert/Dreaming events, as well as use as borongur/totems have been fundamental to keeping them alive and healthy. Nydiyang/white people’s efforts have also contributed materially to the care of these endangered species in recent decades (e.g. Danks 1997). The Reserve sits on the south-eastern edge of the high rainfall heavily forested Country of the south-west. Yet it has been managed thoughtfully in a different way with regards to the use of fire than today’s approach to prescribed burning based on aerial ignition (Bradshaw et al. 2018).

The deliberate exclusion of prescribed burning from Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner is replaced by the use of a wide slashed firebreak across the isthmus of the peninsula on the Reserve. We also know through the Knapp family oral history interviews below that Two Peoples Bay Noongars as well as their northern neighbours from Yillangarup/Boulder Hill performed ceremonies to call up the giant snakes of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, Gardner Creek, and Miialyiin/Angove Lake. That the Tyiurrtmiirity were revered and respected culturally cannot be denied. They had their own Wiernyert/Dreaming stories, considered so important that Alf Knapp taught his grandson (DC) their essential content in modern times. The Knapp family also recounts very large snakes associated with Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, Gardner Creek, and Angove Lake. DC’s description of the dimensions of the snake 5 m long with a big head he once observed with his father four decades ago intriguingly may match those of the fossil species of snake, Wonambi naracoortensis (Palci et al. 2018). Careful study of these fossil snakes suggests that they may have been semiaquatic as well as subfossorial, and they persisted right up to the late Pleistocene in habitats that were cooler and drier than those favoured by a sister genus that went extinct much earlier (Palci et al. 2018). Wonambi fossils have been recovered from Mammoth Cave and Koala Cave on the Leeuwin Naturaliste Ridge south of Margaret River (Scanlon 1995).

Intriguingly, as recorded in a 19th century whaling journal, a harpoonist wrote:

… After breakfast (in December 1849) one boat was lowered in which some shovels and buckets were put, and manned by six men with an officer in charge… and went onshore to clear out a spring of water, and get it ready for taking onboard some 100 or more barrels.

By noon the boat returned reporting the spring clear of mud and weeds but the water would not be fit to put into the casks until next day. The officer reported that on their arrival at the spring, and commencing to cut away the vegetation that had grown around it, a terrible crashing of brush and shrubs was heard, accompanied by loud hissing sounding like escaping steam from a small engine. They all beat a hasty advance backwards, dropping shovels and hatchets…. After getting out on the beach, they saw an immense snake crawling slowly up a slight hill, now and then rearing his head four or five feet above the ground, turning his head from side to side with his large mouth wide open. He said no doubt the snake was not more than twenty or thirty feet long, but it did look like it was a hundred, and seemed in no great hurry to move on. They went back on tiptoes, and worked for a while without touching their heels to the ground, so he said. This bay is named Two Peoples … (Haley 1849–1853, 2013)

Place naming using Merningar Bardok language

There are place names in and around TPBNR that are so clearly powerful that they have persisted to the present day, either through the ethnographic record, oral history or both; Boyankaatup and Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks are two examples (Fig. 1). Here, we aim to enlarge the available Noongar place names in Merningar Bardok based on the rich oral history given below, and the equally rich language resources that persist through oral transmission and the vocabulary of Knapp’s great grandmother, Jakbam, and great uncle, Wandinyilmirnong (Tommy King), as recorded by Bates in the early 1900s (Thieberger 2017). Also, von Brandenstein’s (1988)Nyungar Anew records useful information on the Merningar Bardok language. Using these resources the language will continue, establishing an ongoing respectful connection to the ancestors who were one with the Reserve over countless generations.

Our investigations as to apposite Merningar place names are given in Fig. 1, and in Table 1. We hope that these will be taken up by others.

OCBIL theory hypotheses concerning cross-cultural issues

This study has obtained evidence that supports cross-cultural hypotheses of OCBIL theory. The latest formulation of the theory (Hopper 2023) has three specific hypotheses on cross-cultural matters: (1) First Nations revere sacred uplands; (2) minimise human disturbance of OCBILs; and (3) conserve biodiversity through cross-cultural stewardship. Rational reverence (Laudine 1991) of OCBILs is evident for Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. This is seen in the fundamental Wiernyert/Dreaming story involving the fight between Boyankaatup and Yilberup told below. Moreover, other layers of stories for women or initiated men pertain to specific places on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, and revealed in the Djimaalup/Yiridiyan elopement story, and the floating rock near Naarup/Waterfall Beach for men’s business associated with calling up sharks and whales.

Minimising disturbance is also evident for the OCBIL granites of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, notably the predominant absence of the use of fire for countless generations but for mining activities associated with lizard trap construction (Cramp et al. 2022). Conserving cross-culturally may be achieved in many ways in future management of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

Future management to celebrate and actively involve Merningar Bardok cultural custodians

A way to ensure healthy Country and cultural connections is to involve Noongar Elders and multigenerational family participation in the ongoing management of the land in partnership with contemporary land owners. The fundamental importance of TPBNR as a source of gidj/Taxandria juniperina for spears, for example, encourages us to recommend that places are selected on or near the Reserve where gidj/Taxandria juniperina swamps are managed to retain a succession of slender, straight, regrowth suitable for spear construction. Such sites could be interpreted liberally through appropriate information signs, but most importantly, by the engagement of Noongar guides and rangers, coupled with regular demonstrations of spear making on site. To establish such a program, an Elder-led approach would be essential and could be achieved through agreed cross-cultural collaboration with land managers under the auspices of a Healthy Country Plan developed by Noongars.

The importance of Noongar guides telling their own stories on Country cannot be over-emphasised. This is a powerful demonstration of respect for culture and intellectual property holders, as well as shared commitment to cross-cultural collaboration. Cross-cultural conservation with active participation and leadership from First Nations is a key hypothesis developed to care for old, climatically buffered, infertile landscapes (OCBILs) such as seen on TPBNR’s Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Hopper 2023; Hopper et al. 2024). We see a bright future for the Reserve and its surrounds if this path is followed.

Conversations about caring for Country

We conclude this chapter on the cultural context of TPBNR with rare narrative by the Knapp family. In conversation with SDH, LK, DC, and SC provide a deep, intimate perspective across the time and space of the Reserve. Sixteen oral vignettes shared among friends, in a spirit of friendship and deep respect, illustrate the rich, rewarding collaboration, and crucially important cross-cultural caring for Country.

The oral history accounts that follow are based on transcribed video recordings on Country that were undertaken under the University of Western Australia’s (UWA) Human Ethics Approval RA/4/1/6836. Such approval is based on the principles of prior informed consent, respecting Noongar participants as intellectual property holders, and ensuring open-ended questions with no pressure to answer any particular way. Thus, all video recordings, photographs, and transcriptions belong exclusively to the Knapp family. The family holds the copyright and gives ultimate approval (or not) to publish or otherwise share the information recorded upon request.

As to the veracity of the Knapp family’s oral history, a number of checks rendered them highly credible. Firstly, coming from an oral history cultural tradition, LK and her two children, DC and SC, display remarkably consistent recall. Their memories are formidable. Moreover, ensuring that the sequence and detail is accurate, every telling is vital in First Nations’ oral traditions, as survival often depended upon it. Stories told two decades ago to other recorders such as Goode et al. (2005) were delivered verbatim or nearly so when recorded for this and other projects. Such internal consistency was also reflected in shared consistency among family members.

The recollections of places never visited by the story-teller, but conveyed to her by Elders of the family in the past were another check for consistency among participants. Several times on Country LK would say, ‘I recognise this place’, and before arrival accurately describe what we were about to see. Thirdly, stories told by other Noongar families would contain elements of what the Knapps had conveyed orally, details that not always, but sufficiently often, were recounted to deliver a sense of a shared oral history tradition across Noongar families (e.g. Lullfitz et al. 2021; Rodrigues et al. 2022).

Lastly, some have suggested that LK couldn’t know about a site that was for men’s business only (Goode et al. 2005). Although LK was fastidious in referring such matters to her sons or other males in the family, her father shared many things privately with her around countless campfires that were not for public ears. She has knowledge broader than most women because of her close connection to her father, stemming in large part from when he was nursing her recovery from meningitis contracted when she was taken from her family as a child.

First contact between LK, DC and SC and SDH occurred in February 2013 on a survey of the cultural heritage of Quaranup Peninsula south of Albany (Mitchell 2013). After several years of gradually getting to know each other and building trust, it was agreed that LK’s oral history would be recorded for the family records by SDH and his team at UWA. SC and DC subsequently agreed to participate.

Visits to TPBNR occurred in the context of far-ranging trips between Israelite Bay and Denmark on the south coast on traditional Merningar Bardok lands and waters. On the Reserve, LK and DC chose where to stop and conduct interviews at places at which they felt comfortable sharing and recording stories. This method often prompted memories that otherwise would not have come to mind.

SDH visited the Reserve many times between 1973 and 2024 as a research biologist working mainly on plant life and pollination biology, as well as the ecology of granite outcrops (Hopper et al. 2024). Extensive surveys of the Reserve occurred on foot, by vehicle, and in canoes. Particularly since the November 2015 wildfire on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, evidence of Noongar cultural heritage, including the presence of lizard traps (Cramp et al. 2022), standing stones and stone arrangements, were recorded photographically (Figs 5, 6 and 7) and in notebooks.

Following are verbatim transcripts of oral history discussions among LK, DC, SC, and SDH that elucidate aspects of the Reserve and traditional lifeways practised thereon. They are given verbatim to ensure the words of LK and DC and their sequencing are authentically reported. Essentially their form and structure follow Alf Knapp’s and other Elders’ rendition of the family’s oral history going back countless generations.

Merningar place names (Fig. 1, Table 1) were decided at a workshop on 16 January 2024 involving LK, DC, SC and SDH, and videotaped subsequently (5 March 2024) on the Reserve. The objective was to ensure reconnection with ancestors through the use of Merningar language as conveyed to the authors by family members, and thus to associate names with the oral history stories reported below. This process brought forward memories of past discussions with Alf Knapp and other family members. For example, when the name, Kaiupgidjukgidj, emerged for Moates Lagoon after LK had read von Brandenstein’s (1988) account of disputed waterholes near Israelite Bay, she then recalled her father using Kaiupgidjukgidj to refer to Moates Lagoon. It is perfectly apposite, translated as ‘water spear on spear’, as the Lagoon is surrounded by gidj/Taxandria lanceolata forests, the prime source of wood for spears. Here we use Merningar place names first to respect cultural and temporal priority and continue to include the English place name following a forward slash or in parentheses whenever known.

Part 1. Traditional Knapp camp on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and Nornarup/Nanarup – Lynette Knapp and Stephen Hopper. 16 January 2024

| SH: | Lynette we’ve just finished identifying place names in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and you have a very important family campsite to mention. Could you tell us a bit about where it was and who told you about it? |

| LK: | I used to live at Nanarup on a farm (Camelot), the closest farm to the water, and I often had Aunty Bonnie down (Fig. 3). She used to come and stay with us. She and I walked all the way through the bush (to the east). She knew it very well. She used to say how they used to burn through there and it was like parkland. She also used to say they had a camp over between the sand, the white sand (Tyiurrtyaalup) and the ocean. That’s the camp that you’ve got marked (on the screen, Google Earth). It’s funny to me because we used to also walk along the beach and come out opposite that and sit on a cliff front and watch the dolphins. She was a very fit old lady. I used to crawl under the fences and Aunty Bonnie jumped the fences! She jumped the fences with a 22-rifle on her back, after rabbits. We used to go over there and she used to talk nonstop. I guess coming back at different times helped to reconnect her with the Country that she was used to. The Country that they had those Noongar names for. |

| SH: | So when are we talking? How old were you when they were camped there? |

| LK: | Oh Dion was about four. |

| SH: | Dion you’re 45 now right? So 40 years ago. Early 1980s. |

| LK: | 1984 I believe, because I lost my sister in ’84. |

| SH: | And how long would they camp there at that spot? |

| LK: | Oh they’d possibly camp to rest up. Find some muringe or tucker or food. And rest up for a while. Do some hunting. Just go along fishing. My grandfather was a great fisherman. He used to be able to time the salmon (Arripis trutta) fishing season at most of these spots and this was one of them. When he saw the salmon he used to call the dolphins in. He was a dolphin man. Dolphins used to look after him when he was swimming. And he called the dolphins in by standing waist-deep in water slapping the water and the dolphins used to push all the salmon up on to the beach. So he more or less would have fed that full camp if he was around. And he was a young bloke when all the traditional black fellas was camped out there. |

| SH: | What sort of murring/food ‘tucker’ can you recall eating there apart from fish? |

| LK: | Oh well marron was called murring. They twisted that around and called, from our food word marron (Cherax tenuimanus). The old murring (became) marron. Imagine living on marron! Fish. Just over from that camping area there’s a beautiful bit of salt water full of bream (Acanthopagrus spp.), so in them days you’d catch them on anything. |

| SH: | That was the estuary at Nanarup you’re talking about? |

| LK: | At Nanarup or Nornarup (Fig. 1). Nanarup is today’s word for it but it’s Nornarup – place of black snakes. And there’s lots of pythons there. My family lived off them. We used to eat ‘em. And of course the paandee (Acanthopagrus australis), what we call bream, that’s really paandee, that was prolific. |

| SH: | And plant life, can you recall what you would eat at that particular camp. |

| LK: | Oh there was kooding (Haemodorum discolor), Cummuck (Billardiera heterophylla). Lots of stuff. |

| SH: | Wattle seed I suppose – Acacia cyclops? |

| LK: | Wattle seed yes. Everywhere out there. That was one of the main staple diets of bashing it in with fish to make little fish cakes. |

| SH: | Great. Anything else you can remember about the place of significance? |

| LK: | Oh it’s highly significant. It was especially nice walking through the bush with Aunty Bonnie listening to all her yarns. Amazing. |

Part 2. Gidj – Lynette Knapp and Stephen Hopper yarning about spears on Two Peoples Bay Road. 10 April 2017

| SH: | We’re in Two People’s Bay still, just near the crossing of Two Peoples Bay Road over Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek. And Lynette has a very special plant to talk about here. |

| LK: | I would like to take this opportunity to tell you that around, in the Two People’s Bay area, or particularly over near a lake to the west of here (Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon), which isn’t far off, there’s a special sand dune area that we’ll pull up and have a look at when we go past there. And it was a place where people from other countries, their countries, would come into here, be allowed to stay here, and do trade. And the trade in this area was because the Gidj, this is the Noongar name for spear down here, or Mirningar name for spear down here. And they were farmed from this tree. I don’t know the botanical name for it, but we call it Gidj. |

| SH: | Gidj. So this is Taxandria juniperina. |

| LK: | Lovely. And if they, when they grow like this, but in a thicker denser area, you’ll get a lot of spear sticks out of here. And that, spear sticks weren’t really big either. They were small, almost you know… |

| SH: | What sort of size Lynette? Can you tell or show us? |

| LK: | See this one? See this one? (Fig. 8) This would be the size, but it would… they’d look for things that would be longer than this. |

| SH: | That’s quite thin eh? |

| LK: | Yeah it’s very thin. And that would be the proper stick, spear stick. You see spears made out of stuff like this, but it’s not the right way of doing it. These are the sizes of all these, the spear sticks that were collected from down here. And it was a big trade. It was a huge trade in traditional times. |

| SH: | Did you ever see your grandfather or father make a spear out of this? |

| LK: | Yeah! |

| SH: | Can you describe what they did? |

| LK: | Especially when we were around the fresh swamp areas that were where we travelled and lived around, and out this way. They’d come and collect, but the spear sticks would be a lot taller than this, they’d be like seven foot something. But that’s what they’d look for. The size of that. |

| SH: | And to make a spear what was the process? |

| LK: | Oh they’d cut it down and take it back to their camp fires. Skin ‘em, I mean put them in the fire and skin them at the same time. And the fire, the heat would take out all the little bends, such as this. They’d bang them into place. But most times these ones grew up tall and tall and healthy and long. |

| SH: | So not much time really to convert that into a spear by the looks? It’s pretty straight. |

| LK: | This one’s pretty straight, I’ll let it go. See it’s gonna grow pretty straight. |

| SH: | Yes. |

| LK: | But then we come into the times now, where you can only find these growing by the roadside. They would have put a road right through a great big growth of these trees. And when it’s thicker, it grows, these tend to grow higher. Reaching for the light, especially if they’re thick and dark inside then they grow higher for the light. And they’d be farmed (Pascoe 2014) and used in the trades. Black fellas had big trades in this area. And this is pretty famous for all those trades. |

| SH: | Can you describe the farming? What do you mean by that? |

| LK: | Oh people coming looking for the spears and taking them out. They’d probably look through this little grove here and leave it because I can’t see very many that would of any use unless the ones that I just picked up then grow a bit taller. |

| SH: | Would they use fire to keep them at the right growth stage? |

| LK: | With this, with this stuff the fires, the farm, fire farming that they did way back when, they’d probably all be burnt through but if they could avoid, because they needed that dark area to grow up, they… More often than not fires went through and cleaned them all out. But it probably, with the spindly one, it’d do more damage than anything else to burn them. |

| SH: | Yeah. So they’d actually protect these from fire? |

| LK: | Yes. And because this only grows in fresh water. A lot of our trees that we use are all freshwater trees. They grow only in freshwater and don’t like salt. The paperbark, the paperbark tree is, I think it’s a family of the paper bark tree, or very similar, paperbark tree |

| SH: | That’s a Melaleuca, this is a Taxandria, but they both are in the same family. |

| LK: | Is it? Oh! |

| SH: | The Eucalypt family. |

| LK: | Oh OK! |

| SH: | With Eucalypt-like oils. |

| LK: | But the paperbark grows in briny salty water to clean it, but this stuff likes only freshwater. |

| SH: | Well let’s go further up on the hill and take a look at the Country you’re describing. |

Part 3. View over Lake Gardner and big snake wetlands (Tyiurrtmiirity, Miialyiin) from Tandara Hill – Lynette Knapp and Stephen Hopper yarn. 10 April 2017

| SH: | Can you tell us about this place Lynette? |

| LK: | Well we’re looking back over what they call Lake Gardner. They call that there Mount Gardner. It’s a huge thing in traditional history in Albany and in Western Australia. The part of the old campgrounds and the trade grounds up to the right of me are going back that way but this lake here was a spear collecting area, where people came down for the trade and especially for spears. They were good down here. But we’re looking back over here, over my head, to Boyankaatup (profile) from this view (Fig. 9). And you can still see his head and his face sitting up there in that thing, looking back over towards Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks. And just down here there’s a part of this water system that goes over here as well. And there are snakes. They were so big. I remember, I do know this place because we are friends with the people that own that farm. |

| SH: | That’s Tandara? |

| LK: | Tandara. The farm Tandara. |

| SH: | Yes. |

| LK: | Owned by old man Milgrum who’s just passed away, bless his soul. But there are snakes, water snakes or whatever snakes that are so big they used to swallow sheep or small calves. And this place was renowned for snakes. So it’s very, well quite dangerous. Never walk by yourself round this bush area. Or in this water area. |

| SH: | And the name of the Taxandria juniperina that they made spears out of was? |

| LK: | The Gidj, the Gidj. You can see them growing. They’re actually starting to flower now, and you just see a white tint in all that growth. |

| SH: | So it’s the same name for the spear and for that tree? |

| LK: | Yes. Gidj. That’s where they got the Gidgie word from. |

| SH: | Like Gidgegannup? |

| LK: | Oh Gidgegannup could be, but the name, the Gidj, when you go, when people go spear fishing or whatever and they take Gidgies with them, that’s where it got its name from. The Gidgie sticks. The spear sticks of this area. That’s Noongar, that’s Mirningar language. |

| SH: | Gidj? |

| LK: | Gidj. For spear. |

| SH: | So we’ve got the big trade centre on the dunes to have a look at now. |

| LK: | Yes. Yes. |

Part 4. Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon and Tyiurrtyaalup/dunes – the huge trade camp – Lynette Knapp and Stephen Hopper. 10 April 2017

| SH: | What’s the significance of this place Lynette? |

| LK: | This is the area that I spoke about in the last little bit of video. This is the area where the huge trade camp used to be, and people used to come from their Country, or Countries, to here. They were allowed here, and to trade for those spears that we spoke of (Fig. 10). |

| SH: | From how far away would people come? |

| LK: | Oh, goodness. Central desert probably. |

| SH: | Really? |

| LK: | Yes! We found stone over there that came from the top of Queensland. Stone. |

| SH: | Spears were that good that people would come thousands of kilometres? |

| LK: | Yeah, yes. Thousands of kilometres they’d walk just to do trade, trade down in this area. And that’s what’s left of it all (pointing south to Tyiurrtyaalup/the bare dunes lining the southern shore of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon). Every time I come here it reminds me of the old people. And the way they lived. |

| SH: | So the camps, where would people actually camp? |

| LK: | Where all those dunes are, they’d have their camps all set up over that way. That would be all their Kornts, their Mia-Mias, as they’re called. And that’s what it’s turned into (bare dunes). People will tell you that animals (rabbits) did that but it wasn’t animals at all. It was a huge trade area, this place. But you can see all the fresh water? |

| SH: | Yeah that’s a place called Moates Lagoon these days. |

| LK: | Oh. |

| SH: | By nydiyang/white people. Probably has a good Noongar name? |

| LK: | Yeah, yeah it does. I’ll have to remember, bring it back when I do another thing (subsequently remembered as Kaiupgidjukgidj). But it’s full of fish, full of marron and gilgies (Cherax quinquecarinatus). Full of everything. And the bird life there is second to none, when you go in the quiet areas. But like a lot of places, a lot of people don’t realise how particularly special that is. We go to other countries to see this kind of thing and we can’t even be bothered to look at our own, amazing place. And this, when we were looking at the spear, the Gidj, this is a young one of that plant. And in blossom. When it’s in blossom, the season for it to be in blossom, and specially if it’s hanging over waterways, and the bees and the insects all love these, but they fill up with nectar and pollen and things get heavy and they drop in the water. And that fed all the mullet. All the Mederung. All the Mederung. |

| SH: | So that would be a signal, this flowering? |

| LK: | When this flowers, it was a signal to know that those mullet were biting and taking things off the top of the water. And they’d be fat. The mullet fat was just as prized as the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) fat and the kangaroo fat was as well, for medicinal reasons. |

| SH: | There’s a bulb crop here too? |

| LK: | Yeah, Mean (Haemodorum spicatum). To the Albany, the Albany Mirning people, that blood root that’s called Mean. And it’s connected somehow to why the Mirningar people were called Mirning, because when they ate the blood root it was one of the main staple diets. This would be all red (stroking chin below the mouth) from that. |

| SH: | And your tongue would go purple? |

| LK: | Yeah, your tongue would go purple or red. It’d be horrible tasting but they loved it. But the black stalks you see, are those. |

| SH: | And did you have to cook it or could you eat it raw? |

| LK: | You could eat it raw, but it’d be better cooked because they’re funny tasting things. |

South of Two Peoples Bay Road in the west of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon and Tyiurtyaalup/dunes are where people camped to trade Gidj spears. Also, the red bulbs of mean (Haemodorum spicatum) were a staple in summer, turning peoples’ mouths and lips purple due to the strong red pigmentation. Photos S. D. Hopper.

And you’d have to, well I’d prefer them cooked. I’d just put them on the coals or ashes, they cooked up and that takes most of that tarty taste out. But this time of year they’re not as good as they normally are because they’re getting ready for their wet season.

| SH: | Were there prohibitions on when you could dig it up? |

| LK: | With all plants, yeah. All plants you had to use at certain times of the year. And there were more plants that you could use at any time. But to get the best out of them, they were used, dug up at a certain time of the year. |

| SH: | And so for the Mean? |

| LK: | Mean? |

| SH: | It was a certain time? |

| LK: | Summer. |

| SH: | In the summer was it? That was the best time. |

| LK: | Yeah, mostly summer. And because it was just all year round down here, the winter, they would have dug them up. If I dug one up to eat it, I wouldn’t touch it if it was a pale colour, which is what it is now. You get some that are, these are probably… because they’ve had the sun all day, these are probably OK. |

| SH: | I can imagine the old people, the women and girls digging here. |

| LK: | Oh yeah, they’d love all that. They’d all have a fight over that probably! But there’s also another one that we call Kwerding (Haemodorum discolor), and it’s got different leaves altogether that we will pull up anywhere, dig that up. |

| SH: | This Mean has a round leaf, a round section, like a leek, but Kwerding is flat and bit curly? Is that the shape? |

| LK: | Oh the leaf? |

| SH: | Yeah. |

| LK: | Yeah, that’s got a special leaf. There’s normally one on it that’s curly, which is used, how you can tell the difference between these flat leafed things (pointing to Anarthria and Lepidosperma sedges) and the Kwerding itself. And it grows in gravelly, sandy colour places like this. But more out sort of east of here. |

| SH: | Away from the coast? |

| LK: | Away from the coast. Not all together, that’s not found. We lived on it, so a lot of that wasn’t far off the coast. But sort of gravelly areas. It’s like most plants that have certain things in the soil. |

| SH: | Can you remember a couple of places where you particularly enjoyed eating it? |

| LK: | The Gardiner River area, Bremer, Cape Riche. Oh yeah, most of our walks. Yeah most of our places where we went to sleep, walked around the place, found them all. |

| SH: | What about further inland when you were living at Kebaringup near Gnowangerup? |

| LK: | Yes, yes. Found some inland. Yep, found a bit inland. But they like the gravelly areas. But when they were around here, they’d target mainly the fishing, gilgies and marron. Marron are quite beautiful in there, beautiful. And just up the river, in one of the tributaries to the lake up here, there’s a little red fish, that’s so long (indicating about 3–4 cm long), and a little brown fish up there. |

| SH: | Oh on the Goodga River? |

| LK: | Yeah that one. |

| SH: | Just over the hill? |

| LK: | Yeah. So that’s one of the big tributaries for this. |

| SH: | Fortunately, these dunes system (Tyiurrtyaalup) and the big lake (Kaiupgidjukgidj) are all in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, so they can’t be developed. |

| LK: | OK, awesome. We’re having trouble with people developing whatever. Even the roads are a little bit off-putting because they go through areas and rare plants systems and that’s how we learn, but it’s nice to see that this is still intact. |

| SH: | There’s plenty of Albany pitcher plants (Cephalotus follicularis) here as well. |

| LK: | Yes. |

| SH: | Peaty soils – the pitcher plant loves swamps. |

| LK: | Yeah they like it as well don’t they? They’re a special plant, all plants are special plants because they all belong to somebody’s totem. You know everything’s totemic with us. You know some families belong to, because I’m standing around a variety of stuff that could probably involve about 10 different families. It’s just a different types of things. |

| SH: | I was told by (Goreng man) Aden Eades that Gidj was his totem. Spear was his totem. |

| LK: | OK, awesome. |

| SH: | But some people might have Mean as a totem? |

| LK: | Mean? Yes, definitely. I think that it ran in the Mirning people’s thing, but it was a staple food diet. Trees and things are pretty full in the totemic system, but so are the other, all flowering plants as well. |

| SH: | Right, thanks very much. |

Part 5. Two Peoples Bay beach traditional camp and women’s plants – Lynette Knapp and Stephen Hopper. 10 April 2017

| LK: | We’ve come here today (Two Peoples Bay Beach picnic ground) to the place where the women camped when they were preparing that girl (Yirdiyan) for the wedding. And when we see these stories it’s good because it verifies that the granny-eyed wattle, or whatever they call it, cyclops wattle (Fig. 11). |

| SH: | Yeah, cyclops. |

| LK: | Is the one that tells me and many other people, that the old women used to camp here in this area together. It was the women who carried seeds around in their little bags, for kids to mix in with fish. But this is one of the big camping areas that we were talking about in that story. And you can see that we’re still within earshot of Yilberup. We’ll see. |

| SH: | So this is the main Two Peoples Bay beach picnic area? |

| LK: | Two Peoples Bay beach. Yes. |

| SH: | And you mentioned where they got water from? |

| LK: | Yeah to the west of here, just up there about a 100 m, there’s a little creek that comes out water, that was fresh in them days. And it came from the great lakes over the other side (Moates and Gardner Lakes) where the old camps were and the sand dunes that run out of those lakes. But this plant here is what we call the Yorga’s (women’s) plant, and it’s used in various ways for women. That grows prolifically round here but it also indicates ground water. So where-ever this is you find appropriate places to dig. You almost always dig up, dig up water. So there’s no shortage of water. And this (pointing to the sword sedge Lepidosperma effusum) is also used in basket weaving and women’s business, that I probably can’t explain on camera. But it’s an appropriate plant. It’s women’s plant. |

| SH: | Is it called Gerbain (same as Lepidosperma gladiatum)? |

| LK: | Gerbain. Yeah. |

| SH: | And this is the one that has edible leaf bases? |

| LK: | Yes. |

| SH: | Do you want to show us how to grab something to eat off it? |

| LK: | Well it was a good plant to show the kids how to feed themselves I suppose. And normally you’d look for a young leaf in the centre of things that you just pull out like that. There’s a knack to that. And the white, the white area would be a good source of having a bit of a feed. And water. Pretty moist. Really, really moist. See the water on my skin there? But that’s tucker, bush tucker. |

| SH: | And you’d eat that eh? |

| LK: | Yeah. Yeah you’d eat that. And it’s normally in the middle of the plant. |

| SH: | So can I try? |

| LK: | Oh you can have a go! |

| SH: | Mm it’s a bit… |

| LK: | Taste alright? Yeah, yeah they’d chew that until the white runs out… |

| SH: | Gerbain? |

| LK: | Gerbain! |

LK highlights cyclops wattle (Acacia cyclops) as an indicator of the old women bringing seeds into the main Two Peoples Bay camp to add flavour to meat dishes. The red fleshy material surrounding the seeds in the dry pods make the eye-like appearance. The green pods when rubbed vigorously with water form a soap lather. Also, a form of coastal sword sedge or Gerbain (Lepidosperma effusum) is a women’s plant with edible leaf bases and used for secret business. Photos S. D. Hopper.

Part 6. Kinjaarling, Boyankaatup’s profile at Little Beach, Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks and Waychinicup – Wiernyert/Dreaming stories Lynette Knapp yarning with Stephen Hopper. 10 April 2017

| SH: | We’re situated at Little Beach in Two People’s Bay Nature Reserve and we’re going to talk about the story of this place in a minute but firstly, Lynette, can you tell a little bit about the name for Albany and what it might mean? |

| LK: | OK. My family, we were regulars on the coastline. We used to travel from Denmark in the west, right through to Israelite Bay in the east. The Noongar name that they use for Albany was Kinjaarling (Goode et al. 2005), and was also, there was another word also used- Chenjaarling. Chenj is rain, light rain called Chenj, and it normally happens when somebody that is connected to the Country, someone that’s maybe an Elder, but if they’re connected to this Country, that was this region’s way of crying. And telling people that someone from the Country has died, and sorrow. Tells of sorrow. So when we see the Chenj, we knew that there’s someone gone. |

| SH: | Was it a special sort of rain? |

| LK: | Yeah it was a light, very light misty rain. The type that would soak into you. And we always put it down to being like soaking, and maybe that person getting sick from that, from that kind of weather. And we knew that most Noongars in my time when I was a kid all lived in the bush, they didn’t live in the houses and suburbs. So yeah, they never had that connection with getting wet. But that was called Chenj. |

Kinjaarling means ‘place of rain’, so when you was travelling and someone said

‘Where you going?’ and they said ‘Kinjaarling’ or ‘Chenjaarling’ we knew they were headed to where Albany now is. This is all a part of Albany as well. This area down here. Boyankaatup, that’s one of the people that was involved. They sent him to sleep and he was a sentry. He was the one that was looking out for people, because in one of the families from Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, over in that direction (to the north, Fig. 12), there was a girl and a boy who fell in love and it was taboo. So when the oldies, when the women got hold of that news they decided that that was to stop. So they arranged a marriage for this girl. And they brought her over to Two People’s Bay, where Two People’s Bay now is to get her ready for marriage. And when this other person arrived, this bloke arrived from Kangaroo people, which is out near the Stirlings, she was to leave and get away from the fella, Djimaalap, who is what we call the noisy scrub-bird now. And the noisy scrub-bird is pretty rare down here. He lives in this area, and he was the boy that the girl had to part from. When they were preparing her for marriage, Djimaalap and Boyankaatup decided to come around, sneak around, and he (Djimaalap said to Boyankaatup), he said ‘Can you keep an eye out while I go in and I’ll run away, get my woman back and run away with her. I don’t want her marrying anyone else.’

LK pointing to Boyankaatup’s head in profile at the south-west end of Little Beach on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Boyankaatup is locked in stone looking north at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks. This is a central location for the story of Djimaalap and Yerdiyan, turned into birds for disobeying Elders and attempting to elope, 20 December 2016. Photos S. D. Hopper.

And so, he got Boyankaatup to sit and wait and watch back home to see if anyone was following.

Anyway he (Djimaalup) snuck into camp and got caught. And was punished for that. Punished. The girl eventually had to marry the boy she was intended for. Boyankaatup was turned into stone. That’s him there (pointing to the granite hilltop at the west-southwest end of Waterfall Beach/Little Beach), still keeping an eye on the Country for anyone sneaking in (Fig. 12). And the bloke that wanted his woman back is Djimaalap, which is the noisy scrub-bird. You hear him calling out. He’s still lost, he still calls out looking for his bride-to-be. And this is this whole area.

With Yilberup, Mount Manypeaks, that’s our connection to the astral, astral stuff down here (pointing upwards). That’s our connection to the sky. And the stories of the sky. That’s where there used to be a family of emus, and there was one emu who thought he knew more than everybody else and he boasted about everything and didn’t do the right thing. He broke every law that was around, every black fella law. He was just a silly, naughty person. All the oldies, he made that much trouble, all the Elders got together down in this area and decided to punish him by grabbing him and slinging him up into the Milky Way. And when they did that, you know they told him ‘You can’t stay – you’re just causing too much trouble’. We just want to go along and be normal emus, we don’t wanna be troublemakers. So they grabbed him and they threw him up into the Milky Way, and all the little stars that fell out of the Milky Way to make way for the emu, are all represented by the stone peaks on Yilberup, over in that direction (to the north). And you can see them starting from the hill across there (Yiilangarup/Boulder Hill north-northwest) and going right around. They go into Cheynes Beach (to the north-east). So all those little rocks are from the sky. So that’s our Astral connection.

| SH: | So that’s the rocks above Norman’s (Betty’s) beach? |

| LK: | Norman’s beach yes. |

| SH: | Are the nearest ones? |

| LK: | Yes. |

| SH: | Right around to? |

| LK: | Right around to Cheyne’s Beach. |

| SH: | To Cheyne’s Beach? So the whole Manypeaks National Park as we now call it? |

| LK: | Yeah, yep. Yep. |

| SH: | And I’ll just pan around now to look at those hills. |

| LK: | There’s Yilberup. |

| SH: | That’s Norman’s Beach straight down the pathway. |

| LK: | Yes. |

| SH: | And there’s Manypeaks now coming into view, right around to Cheyne’s Beach and Bald Island. And is there another side to the story of Yilberup as well that you mentioned? |

| LK: | Yilberup is Waychinicup, or what they call Waychinicup now, and Waychinicup that’s there now isn’t the real Waychinicup. Waychinicup is further over. It’s a small beach, long beach, where no one was allowed to go. But my family camped over there, they camped over there, but before, in the traditional times, and the stories that were passed down to me were that it was a healing place. We call it Yilberup. So if anybody was sick or wounded or whatever they’d go over there and heal. But the ones that didn’t go back to the people, would have eventually passed away, which is why they never returned. And the Elders, the men, used to move in looking for these people, and if they were noitch (dead), they’d get them and put them on rafts and float them out in the water. Give them up to the ocean. Because the ocean’s a great big part of our culture. Once we’re finished with our totems here (on land) we take our long journey to this land you see between the sky and the sea (Kooranup). You become part of the sea totems, so it’s pretty high. Mount Manypeaks is a place also of healing plants. Got some healing plants over there and so they heal. But mainly not (relying) on plants. A big thing of healing, you know when we had sores on our feet or our legs, you’d use urine, you’d piddle on your sores, without touching it. Cause once it’s touched it becomes infected. |

| SH: | Infected? |

| LK: | You can’t treat any sore or rashes or anything with it. |

| SH: | So you had a sort of custom almost like a parallel to the Viking burials, with people who are noitch – noitch means passed away? |

| LK: | Yes, yes. But that was only people that were round here, were the only people that did those. |

| SH: | Did that? |

| LK: | Yep. |

| SH: | Put the person who’s passed away on a log raft and pushed them out to sea? |

| LK: | Yes. And you can see in the trees over there, they go (bend) over and their whole branches have got a bit of a hook on the end of it (Fig. 13). And that’s where the old camps used to be, the old healing camps. And that’s all messed up now with the DEC, Department of Environment (now DBCA, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions). They’ve put in campsites and things, and they’ve cleared all our trees. |

| SH: | So what’s the significance of the hooks? |

| LK: | The hooks were where they pull the tree over and hooked them into the ground, you know with stakes. And then they put their bush or paperbark- Yoorl- over the top for protection. |

| SH: | Protection. So the hook would help? |

| LK: | The hook would stay in the ground and keep the tree. |

| SH: | The tree would stay put? |

| LK: | Over like that, yeah. |

| SH: | Yes. So you’d bury the hook basically and hold it in place? |

| LK: | Yeah yeah yeah. You’d get it and stake it down. And the tree would, the longer they left it there, the part of the branch had grown upwards, you know. So I don’t know if there’s any more left there. It would be nice to go over and have a look one day. So we must make Yilberup part of our story. |

| SH: | That sounds like a plan. And just to nail Waychinicup, real Waychinicup, is it past Cheyne Beach caravan park? |