Perceptions and willingness concerning the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in Australian healthcare services

Daniel Demant A B * , Paul Byron C , Deborah Debono A D E F , Suneel Jethani C , Beth Goldblatt G H , Michael Thomson G I Jo (River) River J K

A B * , Paul Byron C , Deborah Debono A D E F , Suneel Jethani C , Beth Goldblatt G H , Michael Thomson G I Jo (River) River J K

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

Abstract

Despite growing recognition of the importance of collecting sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data to improve healthcare access and equity for LGBTQA+ populations, uncertainty remains around how these data are collected, their perceived importance and individuals’ willingness to disclose such information in healthcare settings. The aim of this study was to understand perceptions of the collection of data on sexual orientation and gender identity in healthcare settings across Australia, and individuals’ willingness to provide this data.

A cross-sectional online survey of 657 Australian residents was conducted to assess participants’ attitudes towards SOGI data in healthcare settings, along with preferences for methods to collect these data. Statistical analyses included ANCOVA, Chi-squared tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Participants generally recognised the importance of the collection of basic demographic data to support the provision of health services. Willingness to share SOGI data varied, with significant differences noted across gender, sexual orientation and cultural backgrounds. LGBTQA+ participants expressed greater willingness to provide SOGI data, but only in contextually appropriate situations, and preferred more inclusive data collection methods.

The study shows a context-dependent willingness to provide SOGI data in health care, underscoring the need for sensitive data collection methods. Insights into SOGI data collection attitudes are vital for developing inclusive and respectful healthcare practices. Improved SOGI data collection can enrich healthcare outcomes for diverse groups, informing public health policies and practices tailored to LGBTQA+ needs.

Keywords: cultural competency, data collection, gender identity, health care disparities, health services, patient acceptance of health care, sexuality, SOGI.

Introduction

Disparities in health outcomes between LGBTQA+ (lesbian, gay, Bisexual, trans, queer, asexual) communities and the general population have been well-documented in Australia, including in sexual health, mental health, alcohol and other drug use, as well as physical health (Hill et al. 2020). Although these outcomes are the result of various factors – including minority stress – access to affirming, culturally safe and knowledgeable healthcare services has been highlighted as a key determinant of health equity for LGBTQA+ people (Kuzma et al. 2019; Nowaskie and Sowinski 2019).

An important aspect of providing such health care is the awareness of healthcare providers of the sexual orientation and gender identity of a service user (Grasso et al. 2019). Despite consistent reports of health disparities for LGBTQA+ populations, it is unclear if and how data on sexual orientation or gender identity is routinely collected in health and community settings (Cahill et al. 2014; Saxton et al. 2019). Yet, health data, including health-specific, lifestyle and demographic data, are used to shape clinical services, particularly in primary care, and are touted as a key contributor to improving the quality of care and health outcomes (Steele et al. 2004; de Lusignan and van Weel 2006; Griffiths et al. 2011).

Recently, researchers have also been linking large data sets to identify trends in health outcomes, and requirements for policy and service provision (Thompson et al. 2012; Vasiliadis et al. 2017). However, data on sexual orientation or gender identity are unevenly collected, and there is no certainty on how they are used to inform health and human services, public policy or community action (Maragh-Bass et al. 2017).

In addition to issues related to the collection of data on LGBTQA+ populations, there are pragmatic, ethical, social and legal implications of collecting and linking data (Ruberg and Ruelos 2020). Pragmatically, health practitioners reported feeling uncomfortable inquiring about a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity or, alternatively, tend to assume service users are heterosexual and/or cisgender (Sherman et al. 2014; Wolff et al. 2017). For LGBTQA+ people, disclosing sexual orientation or gender identity in healthcare settings has ethical and privacy implications. It not only involves disclosing personal information, but also risks discrimination. Concealment of identities often occurs as a means of protecting individuals and communities against discrimination, exclusion and violence, as well as a means of managing individual internalised homo- and transphobia (Brooks et al. 2018; Scheffey et al. 2019).

As an example, an integrated review by Bjarnadottir et al. (2017) found that in the majority of reviewed studies, participants were willing to answer routine questions about their sexual orientation and perceived them to be collecting important information; however, fear of negative consequences was identified as a significant barrier. Furthermore, some health services may limit data collection of sexual orientation and gender identity due to concerns about potential ‘backlash’ from the general community (Cahill et al. 2014; Anderson et al. 2023). However, although there are no studies examining potential backlash in Australia, internationally, studies indicate that heterosexual and cisgender service users are less likely to understand the relevance of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data, but most are willing to respond to such questions.

Willingness to respond, and perceived relevance of these questions, appears to depend on demographic factors, including age, with older LGBTQA+ people being less likely to provide such information (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2017). This study examines perceptions and willingness regarding the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data in Australian healthcare services, and explores demographic influences on these attitudes using an anonymous cross-sectional online survey to:

evaluate the perception of the importance of routinely collecting data in healthcare services on sexual orientation and gender identity across populations,

understand the extent to which people are willing to provide information on sexual orientation and gender identity for routine data collection in healthcare services,

understand preferences for the routine collection of data on sexual orientation and gender in healthcare services,

evaluate if demographic factors and current health services use and experience affect both willingness to provide and perceived importance of data on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

All Australian residents aged ≥18 years were eligible to participate in an anonymous cross-sectional online survey between May and July 2023. Participants were recruited through paid and unpaid advertisements on social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter). Additional recruitment of participants was through the market research panel service provided by Qualtrics LLC, which provided a quota sample of the Australian population. No formal power calculation was conducted due to the exploratory nature of the study.

Ethical approval for this research has been granted by the University of Technology Sydney Health and Medical Research Ethics Committee (ETH23-8032), and informed consent was collected from each participant at the start of the survey. Recruitment material, as well as the consent form, stated that the research project is about routine data collection in health services in Australia without specifically mentioning sexual orientation or gender identity to limit social desirability bias in answers and recruitment.

Variables

Participants were asked about their age, sexual orientation, sex recorded at birth, gender identity, Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander Status, country of birth and first language (see Table 1 for detailed description of each variable). A dichotomous variable, LGBTQA+ status, was created using the sexual orientation variable and gender identity/sex recorded at birth variables; please refer to Table 1 for an in-depth description of this process. It is acknowledged that this procedure may hide differences between subgroups; however, this approach was necessary due to small sample sizes for some sexual orientation and gender identity categories. For the purpose of analysis, country of birth and first language were also dichotomised.

| Variable | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Measured in years. Free-text field with validation | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Sex recorded at birth | ||

| Gender identity | ||

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander Status | Question was based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics Standard: Are you Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander? | |

| Country of birth | Drop-down list with countries provided by Qualtrics (note: this list contains 193 choices, which are not reproduced here) | |

| First language | Selection in drop-down menu based on most common languages spoken in Australia as per Australian Bureau of Statistics: | |

| LGBTQA+ status | This variable was created using three variables: sexual orientation, sex recorded at birth and gender identity. All participants with a sexual orientation other than heterosexual were categorised as LGBTQA+, whereas heterosexuals were categorised as ‘all other’. All participants where sex recorded at birth and gender identity was not consistent were recorded as LGBTQA+ (e.g. male recorded at birth and non-binary gender identity); when both were consistent, these were recorded as ‘all other’. |

Participants were asked several questions in relation to routinely collected data in healthcare services, with general (family) practices being used as an example in the survey (see Fig. 1). In the first step, participants’ perceptions of the importance of their doctor knowing personal information about them was gathered across three broad categories:

Demographic information: name, date of birth or age, postal address, email address and Medicare number/expiry date.

Identity-related information: sexual orientation, gender and pronouns, and ethnicity, including whether the person identifies as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and their first language and country of birth.

Health-related information: existing chronic conditions, allergies, and history of surgeries and major hospital stays.

In the second step, participants were asked about the perceived importance of a general practitioner knowing identity-related information to provide high-quality care. In both steps, each item requires a response on an individually-defined Likert-scale from 1 (not important at all) over 3 (moderately important) to 5 (very important).

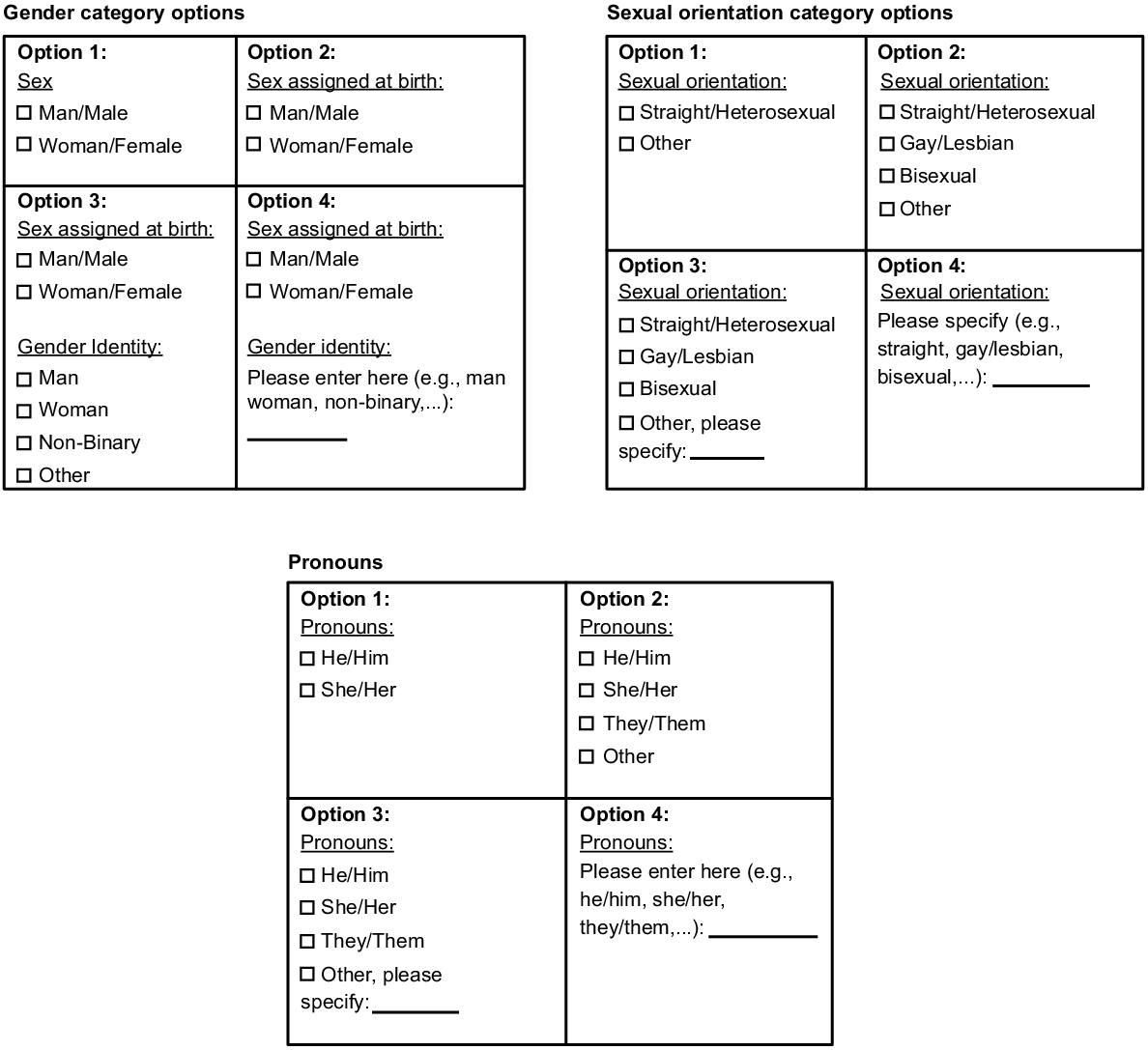

In a final step, participants were presented with four separate options of asking service users about sexual orientation or gender identity (including pronouns), as part of routinely collecting data on registration forms at a medical practice. Participants were presented the options for each of the survey categories in a random order.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, and means with standard deviation for continuous variables. Differences between groups regarding the importance of routinely collected data were analysed using analyses of covariance adjusting for age as relationships between age and importance, as well as between age and other demographic variables (e.g. sexual orientation) were identified. Willingness to provide information was analysed using multinominal logistic regressions with age as a covariate. Wilcoxon signed-rank and Friedman tests were used to analyse the options of asking about sexual orientation, gender identity and pronouns. All assumptions were met and violations of normality were handled through log-transformations. Statistical significance was interpreted to be present using the standard cut-off of 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 691 participants started the survey. Of these, 34 were excluded, as these did not provide data on key demographic variables, leading to a final sample size of 657 participants. Sample characteristics can be found in Table 2.

| Age | 47.8 years (s.d. 18.3) Range: 18–89 | |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 47.8% (n = 314) | |

| Woman | 51.3% (n = 337) | |

| Non-binary | 0.9% (n = 6) | |

| Sex recorded at birth | ||

| Female | 51.8% (n = 337) | |

| Male | 48.2% (n = 317) | |

| Prefer not to say/not relevant | 0.5% (n = 3) | |

| LGBTQA+ status | ||

| No | 85.7% (n = 509) | |

| Yes | 11.1% (n = 66) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2.2% (n = 13) | |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Indigenous | 4.6% (n = 30) | |

| Non-Indigenous | 95.4% (n = 618) | |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 77.7% (n = 509) | |

| Other | 22.3% (n = 146) | |

| First language | ||

| English | 90.6% (n = 595) | |

| Other | 8.7% (n = 57) | |

Perceived importance of routinely collected data (personal)

Table 3 presents the personal perceived importance of routinely collected data across three domains: (1) basic demographic information, (2) identity-related information, and (3) health-related information. Participants rated the importance of basic demographic information, such as name, date of birth and Medicare information, as relatively high, with low variability. Postal address and email address were considered less important with mean scores. Health-related information was also perceived to be very important to be routinely collected for existing chronic conditions, allergies, and history of surgeries and major hospital stays.

| Broad category | Item | Mean (s.d.) | Test statistic A | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | LGBTQA+ | Non- LGBTQA+ | ||||

| Identity-related information | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Status | 2.8 (1.5) | 3.3 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | F (1606) = 4.907, P = 0.027 | |

| First language | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.4) | F (1607) = 5.066, P = 0.025 | ||

| Country of birth | 2.9 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.4) | F (1606) = 1.329, P = 0.250 | ||

| Gender | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.0 (1.2) | F (1606) = 0.001, P = 0.973 | ||

| Pronouns | 2.5 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.4) | F (1606) = 26.148, P < 0.001 | ||

| Sexual orientation | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.4) | F (1606) = 1.049, P = 0.306 | ||

| Basic demographic information | Name | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | F (1606) = 2.187; P = 0.140 | |

| Date of birth/age | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.3 (0.9) | F (1610) = 0.194, P = 0.660 | ||

| Postal address | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.3) | F (1606) = 0.342, P = 0.559 | ||

| Email address | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.3) | F (1605) = 0.105, P = 0.746 | ||

| Medicare number and expiry date | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | F (1606) = 0.297, P = 0.586 | ||

| Health-related information | Existing chronic conditions | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.7) | F (1607) = 1.331, P = 0.249 | |

| Allergies | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.7) | F (1607) = 0.192, P = 0.662 | ||

| History of surgeries and major hospital stays | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.8) | F (1607) = 1.148, P = 0.284 | ||

Identity-related information showed varying importance ratings by participants. Gender had the highest rating, followed by first language, whereas agreement for all other items was below three, with pronouns and sexual orientation being particularly low. Substantial differences between groups were detected for identity-related information. Women overall perceived the importance of routinely collecting data higher than men for Indigenous status (3.0, s.d. 1.5 vs 2.5, s.d. 1.5; P < 0.001), first language (3.5, s.d. 1.4 vs 3.1, s.d. 1.5; P = 0.003), country of birth (3.0, s.d. 1.4 vs 2.8, s.d. 1.4; P = 0.033) and pronouns (2.6, s.d. 1.5 vs 2.2, s.d. 1.4; P = 0.002), whereas no significant difference could be found for collecting information about gender. Similarly, LGBTQA+ participants provided higher ratings than their heterosexual counterparts for Indigenous status (3.3, s.d. 1.5 vs 2.7, s.d. 1.5; P = 0.027), first language (3.7, s.d. 1.2 vs 3.3, s.d. 1.4; P = 0.025) and pronouns (3.5, s.d. 1.4 vs 2.3, s.d. 1.4; P < 0.001), but not country of birth, sexual orientation or gender. People born overseas provided lower ratings than those born in Australia for Indigenous status (2.5, s.d. 1.5 vs 2.8, s.d. 1.5; P = 0.001), first language (2.9, s.d. 1.5 vs 3.4, s.d. 1.4; P < 0.001), country of birth (2.5, s.d. 1.4 vs 3.1, s.d. 1.4; P < 0.001) and pronouns (2.3, s.d. 1.4 vs 2.5, s.d. 1.4; P < 0.001), whereas no differences were found for gender and sexual orientation. Indigenous Australians provided higher ratings for Indigenous status (3.7, s.d. 1.1 vs 3.3, s.d. 1.4; P = 0.001), country of birth (3.7, s.d. 1.3 vs 2.9, s.d. 1.4; P = 0.004) and sexual orientation (3.0, s.d. 1.5 vs 2.4, s.d. 1.3; P = 0.025), but not for first language, gender or pronouns.

Importance of knowing identity-related information for high-quality care

Participants were then asked how important it is for a doctor to know identity-related information for the provision of high-quality care in general (See Table 4). Gender was overall perceived to be important, followed by first language and Indigenous status. Mean ratings <3 were given for country of birth, sexual orientation and pronouns. Significant differences in perceptions were observed between subgroups. Women overall perceived that Indigenous status, and first language and pronouns are more important for high-quality care than men. LGBTQA+ participants also perceived that Indigenous status, and first language and pronouns are more important for high-quality care than their heterosexual counterparts. Indigenous Australians overall perceived Indigenous status, and country of birth and sexual orientation to be more important than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Finally, people born overseas rated Indigenous status, first language, country of birth and pronouns to be less important for high-quality care than their Australian-born counterparts.

| Importance to know for health professionals to provide high-quality care, mean (s.d.) | Test statistic A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | LGBTQA+ | Non-LGBTQA+ | |||

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.4) | F (1606) = 4.642, P = 0.032 | |

| First language | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.4) | F (1606) = 7.383, P = 0.007 | |

| Country of birth | 2.9 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.4) | F (1606) = 0.834, P = 0.362 | |

| Gender | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.3) | F (1606) = 0.889, P = 0.364 | |

| Pronouns | 2.5 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | F (1606) = 18.050, P < 0.001 | |

| Sexual orientation | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.4) | F (1606) = 1.383, P = 0.240 | |

Willingness to provide identity-related information

Participants were also asked about their willingness to provide identity-related information (see Table 5), with two-thirds or more willing to provide identity-related information for all items, with agreement ranging starkly from approximately two-thirds for sexual orientation and pronouns to ≥80% for all other categories (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Status, first language, country of birth and gender). A further meaningful proportion of participants is willing to provide information depending on how the information is asked for, particularly in regard to sexual orientation and pronouns. Differences in willingness to provide this information were also detected between subgroups for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Status, gender, pronouns and sexual orientation, but not for first language and country of birth. In regard to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Status, non-Indigenous participants were more likely (P < 0.001) to be willing to provide this information than their Indigenous counterparts, with 56.0% (n = 14) compared with 80.4% (n = 477), whereas 24% (n = 6) of Indigenous participants stated they would be willing to provide this information depending on the context or situation compared with 5.9% (n = 35) among their non-Indigenous counterparts. Participants born overseas were overall more likely to provide this information than their Australian-born counterparts (85.7, n = 120 vs 77.6%, n = 371; P = 0.001). Regarding gender, sexual orientation did not impact willingness to provide this information; however, LGBTQA+ participants were less likely (P = 0.016) to state that they would not provide this information (3.3%, n = 2 vs 10.8%, n = 59), but would rather decide this based on the situation or context (9.8%, n = 6 vs 2.6%; n = 14). Those born overseas were more likely to be willing to provide this information, with 92.1% (n = 128) and 84.8% (n = 406; P = 0.010), respectively.

| Would provide | Would not provide | Depends how information is asked for | Test statistic A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | LGBTQA+ | Non-LGBTQA+ | Sample | LGBTQA+ | Non-LGBTIQA+ | Sample | LGBTQA+ | Non-LGBTQA+ | |||

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status | 80.1% (486) | 83.6% (51) | 79.7% (435) | 13.5% (82) | 9.8% (6) | 13.9% (76) | 6.4% (39) | 6.6% (4) | 6.4 (35) | X2 (4) = 3.769, NagelkerkeR2 = 0.009, P = 0.438 | |

| First language | 82.6% (502) | 86.9% (53) | 82.1% (449) | 13.3% (81) | 6.6% (4) | 14.1% (77) | 4.1% (25) | 6.6% (4) | 3.8% (21) | X2 (4) = 6.670, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.016, P = 0.154 | |

| Country of birth | 85.3% (518) | 83.6% (51) | 85.5% (467) | 11.2% (68) | 9.8% (6) | 11.4% (62) | 3.5% (21) | 6.6% (4) | 3.1% (17) | X2 (4) = 3.886, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.010, P = 0.422 | |

| Gender | 86.7% (526) | 86.9% (53) | 86.6% (473) | 10.0% (61) | 3.3% (2) | 10.8% (59) | 3.3% (20) | 9.8% (6) | 2.6% (14) | X2 (4) = 12.260, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.033, P = 0.016 | |

| Pronouns | 66.7% (405) | 72.1% (44) | 66.1% (361) | 20.4% (78) | 11.5% (7) | 21.4% (117) | 12.9% (78) | 16.4% (10) | 12.5% (68) | X2 (4) = 14.546, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.029, P = 0.006 | |

| Sexual orientation | 67.4% (409) | 54.1% (33) | 68.9% (376) | 21.7% (132) | 23.0% (14) | 21.6% (118) | 10.9% (66 | 23.0% (14) | 9.5% (52) | X2 (4) = 11.496, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.023, P = 0.022 | |

Regarding pronouns, men were less likely (P = 0.003) to state that they would provide this information compared with women, with 62.5% (n = 183) and 70.5% (n = 227), respectively, while being more likely to make this decision depending on the situation or context (16.0%, n = 47 vs 9.3%, n = 30). Only 20.1% (n = 119) of non-Indigenous participants stated that they would not provide this information, compared with 42.3% (n = 11) among Indigenous participants (P = 0.016). LGBTQA+ people were less likely (P = 0.022) to provide information about their sexual orientation than their heterosexual counterparts, with 54.1% (n = 33) and 68.9% (n = 376), respectively, and were more likely to make this decision based on the context or situation (23.0%, n = 14 vs 9.5%, n = 52).

Preferences regarding data collection on gender, sexual orientation and pronouns

In regard to preferences regarding the collection of data on gender, sexual orientation and pronouns, significant differences were found in the sample between different options with clear rankings for these (see Table 6). Regarding gender, the overall sample preferred gender options clearly marked as sex without differentiating between sex and gender identity. However, LGBTQA+ participants strongly preferred an option that has both sex assigned at birth and gender identity questions above those that do not. A similar pattern can be found in regard to pronouns, where the entire sample and heterosexual participants preferred options that included less choice and tick-boxes over write-in options. Again, LGBTQA+ participants strongly preferred options that provide more choice or are write-ins.

| Category | Option | Full sample | Non-LGBTQA+ | LGBTQA+ participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | Test statistic A | Mean rank | Test statistic A | Mean rank | Test statistic A | |||

| Gender | Option 1 | 2.13 (s.d.1.25) | X2 (3) = 107.610; P < 0.001 | 2.03 (s.d. 1.2) | X2 (3) = 135.984; P < 0.001 | 3.00 (s.d. 1.29) | X2 (3) = 26.893; P < 0.001 | |

| Option 3 | 2.36 (s.d.1.04) | 2.41 (s.d. 1.05) | 2.88 (s.d. .76) | |||||

| Option 2 | 2.62 (s.d.0.86) | 2.58 (s.d. 0.87) | 1.95 (s.d. 0.90) | |||||

| Option 4 | 2.90 (s.d. 1.12) | 2.99 (s.d. 1.01) | 2.18 (s.d. 1.10) | |||||

| Sexual orientation | Option 2 | 2.26 (s.d .0.89) | X2 (3) = 127.083; P < 0.001 | 2.25 (s.d. 1.23) | X2 (3) = 140.852; P < 0.001 | 3.16 (s.d. 1.16) | X2 (3) = 26.421; P < 0.001 | |

| Option 3 | 2.35 (s.d. 1.01) | 2.40 (s.d. 1.02) | 2.46 (s.d. 1.03) | |||||

| Option 1 | 2.35 (s.d. 1.25) | 2.25 (s.d. 1.23) | 1.91 (s.d. 0.82) | |||||

| Option 4 | 3.05 (s.d. 1.11) | 3.11 (s.d. 1.09) | 2.14 (s.d. 1.11) | |||||

| Pronouns | Option 1 | 2.25 (s.d. 1.26) | X2 (3) = 67.183; P < 0.001 | 2.17 (s.d. 1.23) | X2 (3) = 88.108; P < 0.001 | 3.04 (s.d. 1.22) | X2 (3) = 18.442; P < 0.001 | |

| Option 2 | 2.39 (s.d. 0.85) | 2.36 (s.d. 0.85) | 2.64 (s.d. 0.76) | |||||

| Option 3 | 2.48 (s.d.1.06) | 2.53 (s.d. 1.06) | 2.02 (s.d. 1.01) | |||||

| Option 4 | 2.88 (s.d. 1.17) | 2.95 (s.d. 1.15) | 2.30 (s.d. 1.19) | |||||

A slightly different pattern was found for sexual orientation questions, where the overall sample preferred options with more complexity, as long as these are not write-in only, although the simplest option only contained ‘straight/heterosexual’ and ‘others’, and an option with more choice plus a write-in was ranked equally by heterosexual participants. Again, options that provide more complexity were preferred by LGBTQA+ participants.

In an open-ended question at the end of the survey, participants noted the importance of allowing patients to tick a ‘Prefer not to disclose’ option, and highlighted the importance of a disclaimer that clearly outlines the justification or reason as to why these data are collected and how they will be used. Several participants also highlighted the importance of feeling comfortable as a determinant of disclosing their sexual orientation or gender identity, including when and where this information is provided.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the perception and willingness of service users to provide data on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of the routine data collection at health services.

Participants showed varying levels of willingness to share identity-related information. Although basic demographic details were considered important, such as name and date of birth, other factors, such as sexual orientation and pronouns, were perceived as less important. Subgroup differences were observed, with female, LGBTQA+, Indigenous and overseas-born participants expressing distinct perspectives on data collection. Participants showed a significant willingness to share information, especially when considering the context in which the information was requested.

Willingness to provide information on pronouns did not differ significantly between the overall sample and LGBTQA+ participants; however, a significant difference was found for sexual orientation, with LGBTQA+ participants being less likely to be willing to provide this information than their non-LGBTQA+ counterparts, and more likely to base this decision on the context in which the information was asked. This is consistent with previous literature that identified that LGBTQA+ participants may be reluctant to provide this type of information for fear of discrimination and due to having higher levels of privacy concerns regarding this type of information (Barclay and Russel 2017; Bjarnadottir et al. 2017). This suggests that when such information is sought (e.g. on intake forms or within a consultation) and who is requesting it (and whether they are trusted) will impact the level and accuracy of identity-based data that can be collected from LGBTQA+ people in health settings.

The results underscore the importance of how information is collected, with participants expressing varying degrees of willingness to provide data based on the context or situation in which the data collection occurs. This points to the importance of data collection being approached in empathic, affirming and culturally safe ways (Brooks et al. 2018; Ogden et al. 2020). It has been suggested that normalising discussions about sexuality and gender, and ensuring privacy, can encourage open communication (Braybrook et al. 2023). However, normalisation of identity data may also be a key aspect of context.

Discussions about sexual orientation and gender identity in routine data collection may be important for reducing stigma and fostering an inclusive healthcare environment (Maragh-Bass et al. 2017). Studies have shown that, when such data are collected as a matter of standard practice, it becomes a part of the healthcare landscape, eliminating the fear and hesitancy associated with disclosing this information (Aspinall and Mitton 2008; Cahill et al. 2014; Mansh et al. 2019). These findings may also suggest the presence of an ongoing need for health services and/or health providers dedicated to LGBTQA+ communities. Prior research has shown that LGBTQA+ patients often feel more comfortable disclosing sensitive information when interacting with healthcare providers who are perceived as queer/trans-friendly or are themselves members of these communities (McNeil et al. 2012; Kcomt 2019).

Another crucial outcome of collecting data on sexual orientation and gender identity is the avoidance of hetero- and cis-normative assumptions and misgendering. Hetero- and cis-normativity occur when service users are all presumed to be heterosexual and cisgender, which erases the experiences and needs of sexuality and gender diverse people. Misgendering is a harmful practice related to cis-normativity, where individuals are assumed cisgender and referred to using incorrect gender pronouns or identifiers. Studies have consistently demonstrated that such assumptions negatively impact on the relationship between healthcare professionals and service users, and increase barriers to accessing healthcare in future, as well as leading to suboptimal healthcare provision to LGBTQA+ people (Logie et al. 2019; Tabaac et al. 2019; Bracho Montes de Oca et al. 2021). Collecting data may assist in challenging and correcting such assumptions and practices by ensuring that healthcare providers are aware of and respectful of each individual’s identity (Wolff et al. 2017).

Strength and limitations

This is the first comprehensive study researching the perception and willingness of participants to provide data on sexual orientation and gender identity in the context of the Australian healthcare system. Although this study is limited by the self-selective nature of the sample, the sample composition is a quota sample representative of the demographics of the Australian population. Further measurements were taken to avoid social desirability bias in responses by stating that the research project is about routine data collection in health services in Australia without specifically mentioning sexual orientation or gender identity. The sample size did not allow for in-depth analyses of differences for trans and gender diverse respondents due to small sample sizes.

Conclusions

Collecting personal data requires a focus on ensuring privacy, and providing clear explanations to service users regarding data collection and use. In the healthcare context, privacy is paramount, and service users need to feel safe and secure in sharing their personal information. Offering a transparent explanation of why data are collected also helps alleviate concerns and builds trust between service users and healthcare providers, and may reduce the discomfort experienced by health professionals when dealing with LGBTQA+ people.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

Internal funding through the University of Technology Sydney was received to conduct this study. No other funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the significant contributions made by research participants.

References

Anderson JN, Paladino AJ, Robles A, Krukowski RA, Graetz I (2023) “I don’t just say, Hi! I’m gay”: sexual orientation disclosures in oncology clinic settings among sexual minority women treated for breast cancer in the US south. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 39(4), 151452.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Aspinall PJ, Mitton L (2008) Operationalising ‘sexual orientation’ in routine data collection and equality monitoring in the UK. Culture, Health & Sexuality 10(1), 57-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Barclay A, Russel M (2017) A guide to LGBTIQ-inclusive data collection. Available at https://genderrights.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/LGBTIQ-Inclusive-Data-Collection-a-Guide.pdf

Bjarnadottir RI, Bockting W, Dowding DW (2017) Patient perspectives on answering questions about sexual orientation and gender identity: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26(13–14), 1814-1833.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bracho Montes de Oca EA, Deboel S, Van den Bosch L, Verspreet L (2021) “Baby, you were born this way”: LGBTQI+ discrimination in healthcare communication between healthcare provider and patient. The British Student Doctor Journal 5(2), 95-102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Braybrook D, Bristowe K, Timmins L, Roach A, Day E, Clift P, Rose R, Marshall S, Johnson K, Sleeman KE, Harding R (2023) Communication about sexual orientation and gender between clinicians, LGBT+ people facing serious illness and their significant others: a qualitative interview study of experiences, preferences and recommendations. BMJ Quality & Safety 32(2), 109-120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brooks H, Llewellyn CD, Nadarzynski T, Pelloso FC, Guilherme FDS, Pollard A, Jones CJ (2018) Sexual orientation disclosure in health care: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice 68(668), e187-e196.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C, King D, Mayer K, Baker K, Makadon H (2014) Do ask, do tell: high levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS ONE 9(9), e107104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

de Lusignan S, van Weel C (2006) The use of routinely collected computer data for research in primary care: opportunities and challenges. Family Practice 23(2), 253-263.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Shui C, Bryan AEB (2017) Chronic health conditions and key health indicators among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older US adults, 2013–2014. American Journal of Public Health 107(8), 1332-1338.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Grasso C, McDowell MJ, Goldhammer H, Keuroghlian AS (2019) Planning and implementing sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in electronic health records. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA 26(1), 66-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Griffiths P, Maben J, Murrells T (2011) Organisational quality, nurse staffing and the quality of chronic disease management in primary care: observational study using routinely collected data. International Journal of Nursing Studies 48(10), 1199-1210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hill A, Bourne A, McNair R, Carman M, Lyons A (2020) ‘Private lives 3: the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people in Australia.’ (Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University) Available at https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1185885/Private-Lives-3.pdf

Kcomt L (2019) Profound health-care discrimination experienced by transgender people: rapid systematic review. Social Work in Health Care 58(2), 201-219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kuzma EK, Pardee M, Darling-Fisher CS (2019) Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender health: creating safe spaces and caring for patients with cultural humility. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 31(3), 167-174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Logie CH, Lys CL, Dias L, Schott N, Zouboules MR, MacNeill N, Mackay K (2019) “Automatic assumption of your gender, sexuality and sexual practices is also discrimination”: exploring sexual healthcare experiences and recommendations among sexually and gender diverse persons in Arctic Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community 27(5), 1204-1213.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mansh MD, Nguyen A, Katz KA (2019) Improving dermatologic care for sexual and gender minority patients through routine sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. JAMA Dermatology 155(2), 145-146.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Maragh-Bass AC, Torain M, Adler R, Schneider E, Ranjit A, Kodadek LM, Shields R, German D, Snyder C, Peterson S, Schuur J, Lau B, Haider AH (2017) Risks, benefits, and importance of collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in healthcare settings: a multi-method analysis of patient and provider perspectives. LGBT Health 4(2), 141-152.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McNeil J, Bailey L, Ellis S, Morton J, Regan M (2012) Trans mental health study 2012. TREC. Available at http://www.scottishtrans.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/trans_mh_study.pdf

Nowaskie DZ, Sowinski JS (2019) Primary care providers’ attitudes, practices, and knowledge in treating LGBTQ communities. Journal of Homosexuality 66(13), 1927-1947.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ogden SN, Scheffey KL, Blosnich JR, Dichter ME (2020) “Do I feel safe revealing this information to you?”: patient perspectives on disclosing sexual orientation and gender identity in healthcare. Journal of American College Health 68(6), 617-623.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ruberg B, Ruelos S (2020) Data for queer lives: how LGBTQ gender and sexuality identities challenge norms of demographics. Big Data & Society 7(1), 2053951720933286.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saxton P, Adams J, Fenaughty J, Exeter D, Sporle A (2019) P524 Gays, government and big data: should routine health records include sexual orientation? Sexually Transmitted Infections 95, A1-A239.

| Google Scholar |

Scheffey KL, Ogden SN, Dichter ME (2019) “The idea of categorizing makes me feel uncomfortable”: university student perspectives on sexual orientation and gender identity labeling in the healthcare setting. Archives of Sexual Behavior 48(5), 1555-1562.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sherman MD, Kauth MR, Shipherd JC, Street RL, Jr (2014) Provider beliefs and practices about assessing sexual orientation in two veterans health affairs hospitals. LGBT Health 1(3), 185-191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, Evans M (2004) Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Medical Care 42(10), 960-965.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tabaac AR, Benotsch EG, Barnes AJ (2019) Mediation models of perceived medical heterosexism, provider–patient relationship quality, and cervical cancer screening in a community sample of sexual minority women and gender nonbinary adults. LGBT Health 6(2), 77-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thompson SC, Woods JA, Katzenellenbogen JM (2012) The quality of Indigenous identification in administrative health data in Australia: insights from studies using data linkage. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 12, 133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vasiliadis H-M, Diallo FB, Rochette L, Smith M, Langille D, Lin E, Kisely S, Fombonne E, Thompson AH, Renaud J (2017) Temporal trends in the prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD in children and young adults between 1999 and 2012 in Canada: a data linkage study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 62(12), 818-826.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wolff M, Wells B, Ventura-DiPersia C, Renson A, Grov C (2017) Measuring sexual orientation: a review and critique of US data collection efforts and implications for health policy. The Journal of Sex Research 54(4–5), 507-531.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |