Self-reported hearing loss in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults: unmeasured, unknown and unmanaged

Alice M. Pender A B C * , Philip J. Schluter

A B C * , Philip J. Schluter  A D , Roxanne G. Bainbridge

A D , Roxanne G. Bainbridge  E , Geoffrey K. Spurling

E , Geoffrey K. Spurling  A F , Wayne J. Wilson

A F , Wayne J. Wilson  B , Claudette ‘Sissy’ Tyson F and Deborah A. Askew

B , Claudette ‘Sissy’ Tyson F and Deborah A. Askew  A

A

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

Effective management of hearing loss in adults is fundamental for communication, relationships, employment, and learning. This study examined the rates and management of self-reported hearing loss in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.

A retrospective, observational study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged ≥15 years who had annual health checks at an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary healthcare clinic in Inala, Queensland, was conducted to determine self-reported hearing loss rates by age and ethnic groups stratified by sex. A medical record audit of patients who self-reported hearing loss from January to June 2021 was performed to identify current management approaches, and the proportion of patients that were appropriately managed.

Of the 1735 patients (average age 40.7 years, range 15.0–88.5 years, 900 [52.0%] women) who completed 3090 health checks between July 2018 and September 2021, 18.8% self-reported hearing loss. Rates did not differ between men and women. However, significant effects were noted for age, with rates increasing from 10.7% for patients aged 15–24 years to 38.7% for those aged ≥65 years. An audit of 73 patient medical records revealed that 39.7% of patients with self-reported hearing loss were referred to Ear, Nose and Throat/audiology or received other management. A total of 17.8% of patients owned hearing aids.

Only 40% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults who self-reported hearing loss were referred for management. Significant changes to clinical management and government-funded referral options for hearing services are required to improve the management of self-reported hearing loss in this population.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, chart review, Indigenous adults, management, primary health care, quantitative investigation, self-reported hearing loss, urban health.

Introduction

One in five people experience hearing loss globally (World Health Organization 2021). Hearing loss is associated with poor mental health, dementia (Lin and Albert 2014), and reduced quality of life (Fellinger et al. 2005). Hearing loss is treatable with many available management options. Effective management of hearing loss in adults is fundamental for communication, relationships, employment, and learning.

There is a range of barriers to accessing hearing health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Burrow and Thomson 2003; Burns and Thomson 2013). Colonisation and ongoing systemic racism have led to socio-economic and political barriers, which affect physical and mental health, education, employment, and accessing health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (King et al. 2009; Parker 2010). The social, economic, and environmental disadvantages have resulted in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population arguably experiencing the highest rates of middle ear disease and hearing loss in the world (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2010). The consequences of untreated hearing loss can be profound for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, because hearing loss can compound these social disadvantages (Hogan et al. 2009).

There is limited robust evidence available on rates of hearing loss in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (Pender et al. 2023). The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 (NATSIHS) found that self-reported hearing loss in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults increased with age from 6.5% in 15–24-year-olds to 29.5% in ≥55-year-olds (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019). The NATSIHS did not include subsequent management of hearing loss, despite the availability of management options in Australia known to benefit hearing (Niemensivu et al. 2015).

Primary healthcare (PHC) services are often the first point of contact with the health system. They provide preventative health care and identify chronic conditions, such as hearing loss, for many Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC services are well placed to diagnose and support management of hearing loss for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (Bennett et al. 2021), particularly through the provision of annual health checks (HCs). There is a lack of understanding and information on the extent of hearing loss in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults and available management pathways for them. Given the compounding effects hearing loss has on existing social inequities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, the present study aimed to measure rates of self-reported hearing loss and the subsequent management of persons self-reporting hearing loss in a large, urban Indigenous PHC service. We aim to use this research to make changes to the delivery of aural health care at the local level to ensure better hearing outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective repeated measures analysis of annual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander HC data from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC service, and a subsequent electronic medical record (EMR) audit from a sample of individuals self-reporting hearing loss were conducted.

As authors, we acknowledge our various positions as both insiders and outsiders of the research project as university researchers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members, clinicians, and employees of the Indigenous primary health care clinic where this research took place. We conducted this study alongside other related studies to obtain baseline data with the view of using the results for quality improvement of hearing service delivery.

Setting

The study was conducted at the Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (COE), a Queensland Government PHC facility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples located in south-west Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Participants

Participants were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged ≥15 years who attended the COE for at least one HC from 1 July 2018 to 30 September 2021.

All patients reporting hearing loss/difficulties in a HC from 1 January 2021 to 30 June 2021 were included in the EMR audit. This date range was chosen to allow time for health professionals actioning hearing loss to correspond with the COE, so that their correspondence could be included in the audit.

Procedure

All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples attending the COE are offered a HC (Supplementary material S1) every 9 months. HCs gather information on clinical findings, social aspects, lifestyle aspects, and health measures for diagnosis and prevention of health conditions, and have been computerised since 2010 (Spurling et al. 2013). The HC starts with a nurse securing consent and asking initial questions. It finishes with a general practitioner (GP) reviewing the answers and asking further questions. A ‘Problem List’ is automatically generated, and the HC data are stored in the patient’s medical record for follow up by a GP.

The EMRs of patients who self-reported hearing loss were manually audited to identify follow-up actions triggered by the disclosure of hearing loss. Patients identified during the EMR audit as requiring subsequent audiological care were noted, so that they could be contacted for audiology review at the COE.

Statistical analysis

Our selection of the variables extracted from the HC database were informed by REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) guidelines (Benchimol et al. 2015). HC data were deidentified, securely transmitted and imported into Stata version 16 (StataCorp 2019). HCs repeated within 6 months (including duplicates) were excluded. Descriptive analyses of patient demographic data from first eligible HCs were completed and compared with the 2021 greater Brisbane area Australian Bureau of Statistics census estimates (Table 1; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022). Self-reported hearing loss data were analysed and stratified by sex. Multilevel modified Poisson regression analyses with robust variance estimators and repeated HCs nested under patients were used to estimate self-reported hearing loss rates. This analytic approach negates the bias introduced by conventionally employed logistic regression models when the outcome of interest is not rare. Polynomial changes in self-reported hearing loss over time were initially examined and tested using Wald’s type III test. All analyses were performed at the 5% significance level (two-sided).

| COE sample | 2021 Census data for greater Brisbane | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| SexA | |||||

| Female | 900 | (52.0) | 25,947B | (50.8C ) | |

| Male | 832 | (48.0) | 25,130B | (49.2C ) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 15–24 | 412 | (23.7) | 15,030 | (29.4) | |

| 25–34 | 307 | (17.7) | 11,811 | (23.1) | |

| 35–44 | 284 | (16.4) | 8072 | (15.8) | |

| 45–54 | 356 | (20.5) | 7352 | (14.4) | |

| 55–64 | 231 | (13.3) | 5095 | (10.0) | |

| ≥65 | 145 | (8.4) | 3717 | (7.3) | |

| EthnicityD | |||||

| Aboriginal | 1,552 | (91.5) | 68,437C | (88.9) | |

| Torres Strait Islander | 43 | (2.5) | 3957C | (5.1) | |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 102 | (6.0) | 4549C | (5.9) | |

Patients’ medical records were accessed and examined. The following variables were included in the EMR audit: hearing loss (patients were asked: ‘Do you have hearing loss?’ [July 2018 to September 2019], or ‘Have you noticed trouble/difficulty hearing?’ [October 2019 to September 2021]); age (calculated from date of HC to date of birth), sex (as listed in EMR), and ethnicity (self-identified). If the most recent HC revealed no evidence of follow up/management following self-report of hearing loss, then the EMRs were examined to determine the date of first report of hearing loss in the previous HCs. The patient’s EMR was then checked from that date onwards for evidence of follow-up activities.

The following components of the patients’ EMR were reviewed from the date of first report of hearing loss: (1) referral to audiology/hearing clinic, (2) correspondence (report/results) from the hearing specialist to whom patient was referred, and (3) patient report/comments at COE follow-up visit. From these components, the following variables were extracted into a separate Excel spreadsheet:

age at time of HC

age range

sex

date of HC of first instance of self-reported hearing loss

hearing comments

otoscopy comments

GP action (referral to audiology/hearing clinic, referral to Ear, Nose and Throat specialist, other)

attendance at hearing clinic

evidence of attendance at hearing clinic

hearing loss present on audiogram

fitting of a hearing device

use of hearing device

evidence of use of hearing device

patient’s reported satisfaction with hearing device

other comments.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty principles, ensuring that the priorities of the communities were actively acknowledged and addressed. The study builds on our prior qualitative research involving interviews with community members, which revealed that many individuals had never had their hearing assessed, whereas others did not obtain hearing aids until middle age despite hearing issues since childhood (A. M. Pender, R. G. Bainbridge, C. ‘S’. Tyson, G. K. Spurling, W. J. Wilson, P. J. Schluter, and D. A. Askew, unpubl. data). Community approval was obtained from the Inala Community Jury for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research (Bond et al. 2016) to conduct the study and for publication. Ethics approval was obtained from Metro South Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/2019/QMS/51446) and ratified by The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (2020000844). A waiver of consent for the retrospective HC data was obtained so that we could use routinely collected clinical data as permitted under the Queensland Public Health Act. Public Health Act approval was granted for us to access the EMRs (PHA 51446).

Results

The research dataset contained records from 1735 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults aged ≥15 years who completed 3031 HCs (following the exclusion of 41 duplicate HC records and 18 HCs repeated within 6 months). Table 1 shows participant demographics and comparable demographic data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the greater Brisbane area (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022). Overall, 928 (53.5%) patients had one HC within the study period, 416 (24.0%) had two, 294 (16.9%) had three, 96 (5.5%) had four, and 1 (0.1%) patient had five HCs. Average patient age at first HC was 40.7 years (range 15.0–88.5 years), and median inter-HC time was 11.9 months (Q1 10.3, Q3 15.6 months, largest interval 3.1 years).

Self-reported hearing loss

Valid self-reported hearing loss data were available from 2967 (97.9%) HCs. Of the first HCs, 1701 patients had valid responses, with 320 (18.8%) self-reporting hearing loss. There were no significant linear (P = 0.70) or quadratic (P = 0.16) temporal changes in self-reported hearing loss over the study period, and no significant patterns in missing values at first HC by age (P = 0.09), sex (P = 0.30), or ethnicity (P = 0.33).

Table 2 shows the estimated relative risks (RRs) for self-reported hearing loss for all patients and stratified by sex. Rates of self-reported hearing loss increased with age for both females (P < 0.001) and males (P < 0.001), with rates being 3.1 (95% CI: 2.1–4.5) times higher in females aged ≥65 years versus females aged 15–24 years, and 4.5 (95% CI: 2.9–7.1) times higher in males aged ≥65 years versus males aged 15–24 years. Rates were not affected by whether the patients were Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, or both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander for males (P = 0.82) or females (P = 0.85, although statistical power was limited by most patients identifying as Aboriginal). The results remained consistent over time in patients who attended multiple HCs (ICC = 0.68).

| Overall | Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 15–24 | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | |

| 25–34 | 1.2 | (0.8–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.0) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.8) | |

| 35–44 | 1.1 | (0.8–1.6) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.2) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.5) | |

| 45–54 | 1.9 | (1.4–2.5) | 1.7 | (1.2–2.6) | 2.1 | (1.3–3.3) | |

| 55–64 | 2.5 | (1.8–3.3) | 2.4 | (1.6–3.6) | 2.5 | (1.5–4.0) | |

| ≥65 | 3.6 | (2.7–4.9) | 3.1 | (2.1–4.5) | 4.5 | (2.9–7.1) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Aboriginal | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | |

| Torres Strait Islander | 0.9 | (0.5–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.4) | |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.8) | |

Table 3 shows the estimated rate of self-reported hearing loss by age group derived from the analyses above with rates ranging from 11.2 to 34.4% for females and 8.7 to 46.3% for males.

| Overall | Females | Males | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Rate (%) | (95% CI) | n | Rate (%) | (95% CI) | n | Rate (%) | (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–24 | 412 | 10.7 | (8.3–13.8) | 219 | 11.2 | (8.0–15.7) | 192 | 10.3 | (6.9–15.3) | |

| 25–34 | 307 | 12.8 | (9.7–16.7) | 163 | 14.6 | (10.4–20.5) | 143 | 10.3 | (6.7–16.0) | |

| 35–44 | 284 | 11.7 | (8.9–15.5) | 126 | 15.5 | (10.8–22.3) | 158 | 8.7 | (5.7–13.2) | |

| 45–54 | 356 | 20.1 | (16.7–24.2) | 186 | 19.5 | (15.0–25.3) | 170 | 21.3 | (16.5–27.5) | |

| 55–64 | 231 | 26.3 | (21.6–31.9) | 124 | 27.0 | (21.0–34.9) | 106 | 25.5 | (18.9–34.5) | |

| ≥65 | 145 | 38.7 | (31.9–46.9) | 82 | 34.4 | (26.4–44.9) | 63 | 46.3 | (35.2–61.0) | |

COE, Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care.

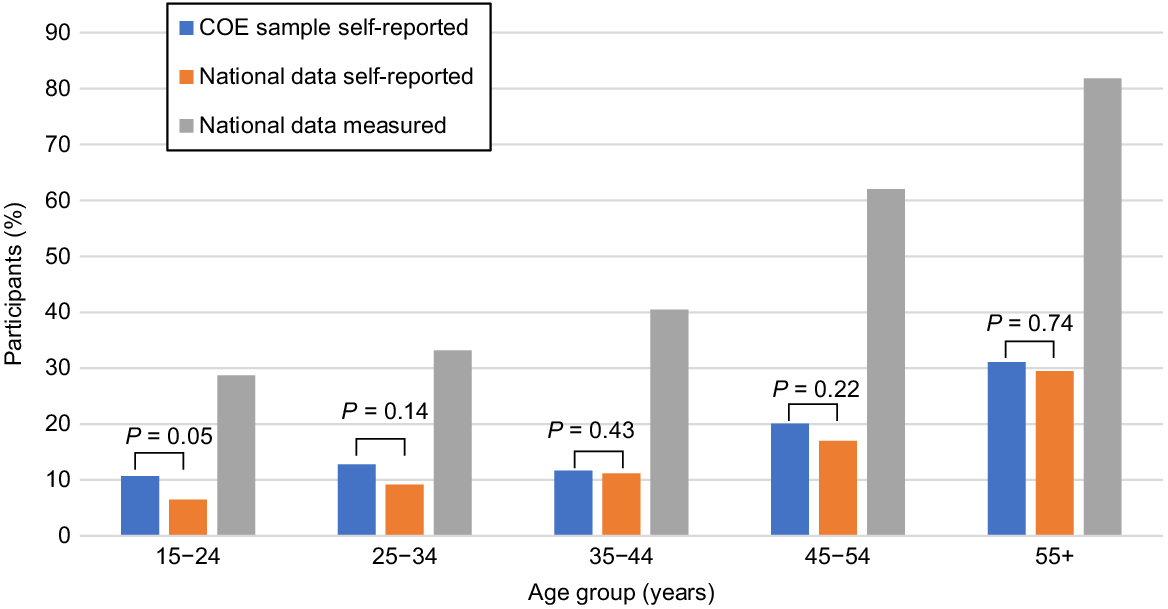

Fig. 1 gives the estimated rates of self-reported hearing loss for the present study, and estimated rates of self-reported and measured hearing loss reported in the NATSIHS 2018–19 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019). The study’s estimated rates of self-reported hearing loss were consistent with those reported in the national data, and both were considerably less than the estimated rates of measured hearing loss reported in the national data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults. All three sets of estimates show a clear age effect.

Estimated rates of self-reported hearing loss for the present study, and estimated rates of self-reported and measured hearing loss reported in national Australian data (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019).

EMR audit

From 1 January 2021 to 30 June 2021, 74 patients self-reported hearing loss in a HC. One patient was excluded from the EMR audit because of restricted access to their EMR.

The median age of the 73 eligible patients in the EMR audit was 53 years (range 15–84 years), with 58.9% females. The distribution of patients was unchanged over age groups (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.63).

Of the 73 patients, 44 (60.3%) showed no record of follow up. Of the 29 (39.7%) patients who obtained appropriate medical treatment or proceeded to ear and/or hearing services, the actions taken by the GPs included: referring to audiology (n = 19, 26.0%), Ear, Nose and Throat specialist (n = 8, 11.0%), hearing screening services (n = 7, 9.6%), radiology (for magnetic resonance imaging, n = 1, 1.4%), and tinnitus services (n = 1, 1.4%); scheduling a review appointment for assessment of ongoing symptoms (n = 1, 1.4%); and/or recommending wax softener to reduce external auditory canal cerumen (n = 2, 2.7%). Some patients received more than one referral and/or recommendation.

The proportion of patients receiving appropriate management was not affected by sex (34.9% females, 33.3% males, Fisher’s exact test P = 1.0), but was affected by age with a higher percentage of younger (<26 years) and older adults (≥50 years) appropriately managed (40%), compared with 21.7% of patients aged between 26 and 49 years being appropriately managed (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.19).

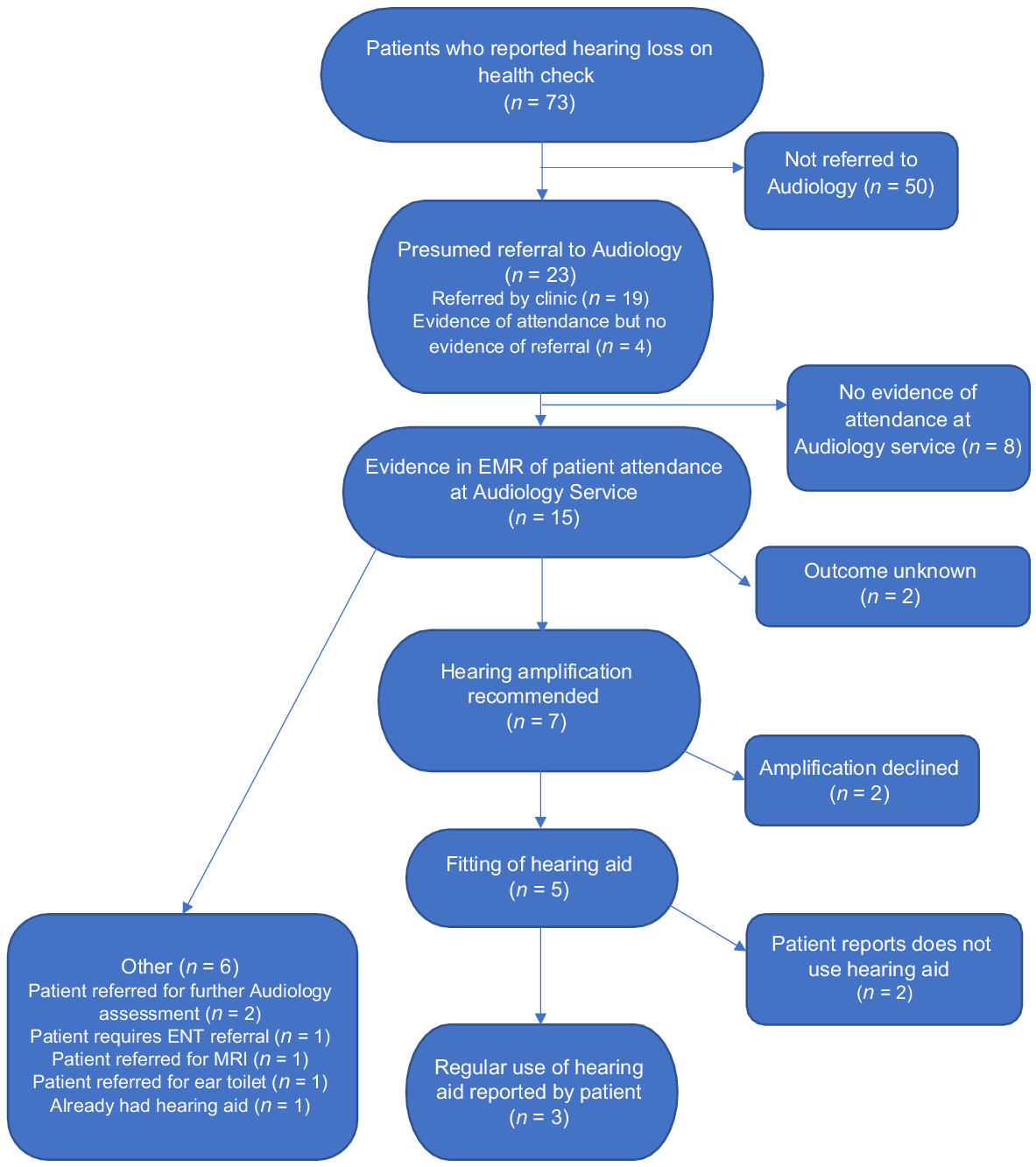

Fig. 2 depicts the patient flow from self-report of hearing loss in the HC through to audiology management as determined by the EMR audit. Nineteen (26.0%) patients were referred to audiology, 14 (19.2%) of whom attended. Four (5.5%) other patients had evidence of audiology attendance shortly after their HC, but no evidence of referral. Three of the 73 patients had a record of previously attending audiology prior to HC. One patient who reported a broken hearing aid was not re-referred to audiology.

Flow diagram of patients’ journey through Audiology services from reporting hearing loss to management of hearing loss.

Of the 18 patients who attended an audiology clinic following self-reported hearing loss, seven (38.9%) were recommended hearing aids and five (27.8%) received hearing aids. Three of the five (60.0%) reported regularly using their hearing aids.

In addition to the five patients who received hearing aids, there were another eight patients found in the audit who already had hearing aids (13 in total [17.8%]). Eight (61.5%) of these 13 patients self-reported using their hearing aid regularly, and three (23.1%) reported that their hearing aids were broken, but these patients were not referred back to audiology.

Discussion

Overall, 18.8% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in our sample self-reported hearing loss, and ~60% who reported this loss during a HC received no management. Positive outcomes were noted in the 40% who did receive management. Rates of self-reported hearing loss among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults attending the COE increased with age from 10.7% in those aged 15–25 years to 38.7% in those aged ≥65 years. This result is comparable with the national average for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019). No statistical associations were found between self-reported hearing loss and sex, despite evidence of older males having greater risk of hearing loss (Villavisanis et al. 2020).

The rate of measured hearing loss was 2.5–5 times higher than the rate of self-reported hearing loss in both the present study and the NATSIHS (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019). This finding suggests that many adults with hearing loss do not self-report, which is supported by other research suggesting that self-reported hearing loss underestimates actual hearing loss, including in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (Harkus 2016). This would suggest that hearing loss affects a considerable proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.

Federal government funding for hearing services is only available for pensioners, Veteran Gold/White Card holders, Community Development Employment Projects participants, people aged <26 years or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged ≥50 years. This study revealed that appropriate management in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults who were eligible for funding (40.0%) was almost twice that of those not eligible for funding (21.7%). Although this measured effect size is large, the relatively small sample numbers means that this difference was not significant and might be because of chance alone. However, it warrants further investigation and attention, because it implies that lack of funded services negatively affects referral for management and is a barrier to access to appropriate hearing health care.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is the first to examine management of hearing loss in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in a PHC service, and the first study in over a decade to report hearing loss rates in a localised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult population. Its relatively large (repeatedly measured) patient population with high coverage and good representation provides robust evidence, and makes an important contribution to this underresearched area of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health (Pender et al. 2023). Because this study examined one urban setting, findings might not be generalisable to other urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medical services.

Research translation has already begun based on these findings. One service improvement strategy actioned by the COE is the addition of an automated alert system in the HC to prompt GPs to actively manage self-reported hearing loss in patients. Another improvement has been a change of wording of the hearing question in the HC from ‘Do you have hearing loss?’ to ‘Have you noticed trouble/difficulty hearing?’. The intent is to improve detection of self-reported hearing loss. However, an increased rate of hearing loss was not observed after changing the wording in the present study.

Implications for clinical practice and policy

Although we were unable to determine why 60.3% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults who self-reported hearing loss during their HCs did not proceed to ear and/or hearing services in the current study, we identified the urgent need for improved access and clearer referral pathways to ear and/or hearing services for this at-risk population. Further sense-making of these data will occur as part of the broader study in a knowledge mobilisation and real-world service improvement activities. Hearing loss is treatable through amplification (e.g. hearing aids), assistive devices and informational counselling, with studies showing that treatment improves quality of life (Niemensivu et al. 2015; Manrique-Huarte et al. 2016), and is accepted by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults living in urban, regional and remote areas throughout Australia (Australian Hearing: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services 2017). Negative perceptions of hearing aids have been reported in some adolescent populations (Strange et al. 2008); however, aesthetics of hearing aids have improved since this study and there is no currently available research data on this.

This research is particularly important in the light of a growing evidence base linking hearing loss to the risk of dementia (Lin and Albert 2014; Nadhimi and Llano 2021). Rates of dementia are higher in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults because of the social determinants of health that contribute to poorer health outcomes that affect dementia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024). The Alzheimer’s Research UK issued five recommendations for the government to address the social determinants of health that affect dementia, and one of these is the provision of routine screening for hearing loss and treatment when necessary (Alzheimer’s Research UK 2023).

Improved education of primary care providers on the benefits of aural rehabilitation is also required. Primary care providers’ attitudes and perceptions of hearing loss play an important part in its management. Australian primary care providers are aware of the consequences of hearing loss, but are not convinced of the benefits of aural rehabilitation (Gilliver and Hickson 2011). Referral practices for hearing loss for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 26–50 years could also be affected by the lack of government funding for hearing services (i.e. hearing aids). Funding is a significant issue given this age group’s high parental and work responsibilities (Askew et al. 2019). Urgent action is required to change government policies to ensure all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults are eligible for funding for aural rehabilitation.

Conclusion

This study shows that hearing loss in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults is undermeasured, underreported, and undermanaged. Clear guidelines for referral pathways and management of hearing loss in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult population are needed to improve access to successful management options available in Australia. Almost one in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults attending an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary healthcare service self-reported hearing loss, but the majority of these had no referral to hearing services. Significant improvements are required in the management of self-reported hearing loss in this population, including changes to clinical management and government-funded referral options for hearing services.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

The study was partly funded by a Queensland Advancing Clinical Research Fellowship, and the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital and RBWH Foundation Scholarship awarded to Alice Pender.

Acknowledgements

The research team acknowledge the Yuggera people as the Traditional Owners of the land where this research was conducted. The team gratefully acknowledges the Inala Community Jury for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research for their advice and governance over the project and data.

Author information

Alice Pender is a non-Indigenous Australian conducting this research as part of her PhD candidature. Roxanne Bainbridge is a Gunggari researcher from western Queensland. Claudette ‘Sissy’ Tyson is a Kuku Yalanji researcher and part of the Inala Aboriginal community. Wayne Wilson and Geoffrey Spurling are non-Indigenous Australians of European descent, and Deborah Askew and Philip Schluter are Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent).

References

Alzheimer’s Research UK (2023) Towards brain health inequality. How can governments tackle inequalities in dementia risk? Available at https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Health-inequalties-full-report.pdf [Accessed 29 January 2024]

Askew D, Jennings W, Hayman N, Schluter P, Spurling G (2019) Knowing our patients: a cross-sectional study of adult patients attending an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary healthcare service. Australian Journal of Primary Health 25, 449-456.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey – Statistics about long-term health conditions, disability, lifestyle factors, physical harm and use of health services. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4715.0Main%20Features82018-19?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4715.0&issue=2018-19&num=&view= [Accessed 17 May 2023]

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) Greater Brisbane: Latest release – 2021 Census Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people QuickStats. Available at https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/IQS3GBRI [Accessed 27 March 2023]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) Primary health care in Australia. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/primary-health-care-in-australia [Accessed 17 May 2023]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Dementia in Australia - Burden of disease due to dementia among First Nations people. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/dementia-in-priority-groups/bod-dementia-first-nations-people [Accessed 28 January 2024]

Benchimol E, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, Sørensen H, von Elm E, Langan S, the RECORD Working Committee (2015) The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement in press. PLoS Medicine 12, e1001885.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bennett RJ, Barr CM, Conway N, Fletcher S, Rhee J, Vitkovic J (2021) Promoting hearing loss support in general practice: a qualitative concept-mapping study. Public Health Research & Practice 31, e3152131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bond C, Foley W, Askew D (2016) “It puts a human face on the researched” – A qualitative evaluation of an Indigenous health research governance model. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40(S1), S89-S95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Burns JF, Thomson NJ (2013) Review of ear health and hearing among Indigenous Australians. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin 13(4), 1-22 Available at https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/healthinfonet/getContent.php?linkid=65214&title=Review+of+ear+health+and+hearing+among+Indigenous+Australians [Accessed 12 June 2024].

| Google Scholar |

Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Dobner U, Gerich J, Lehner R, Lenz G, et al. (2005) Mental distress and quality of life in a deaf population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40, 737-742.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gilliver M, Hickson L (2011) Medical practitioners’ attitudes to hearing rehabilitation for older adults. International Journal of Audiology 50, 850-856.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harkus S (2016) Services and gaps in ear health and hearing. Available at https://www.naccho.org.au/app/uploads/2023/08/Australian-Hearing-QAIHC.pdf [Accessed 30 August 2023]

Hogan A, O’Loughlin K, Davis A, Kendig H (2009) Hearing loss and paid employment: Australian population survey findings. International Journal of Audiology 48, 117-122.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

King M, Smith A, Gracey M (2009) Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 374, 76-85.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lin FR, Albert M (2014) Hearing loss and dementia – who is listening? Aging & Mental Health 18, 671-673.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Manrique-Huarte R, Calavia D, Huarte Irujo A, Girón L, Manrique-Rodríguez M (2016) Treatment for hearing loss among the elderly: auditory outcomes and impact on quality of life. Audiology and Neurotology 21(Suppl 21), 29-35.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Nadhimi Y, Llano DA (2021) Does hearing loss lead to dementia? A review of the literature. Hearing Research 402, 108038.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Niemensivu R, Manchaiah V, Roine RP, Kentala E, Sintonen H (2015) Health-related quality of life in adults with hearing impairment before and after hearing-aid rehabilitation in Finland. International Journal of Audiology 54, 967-975.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Parker R (2010) Australia’s Aboriginal population and mental health. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 198, 3-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pender AM, Wilson WJ, Bainbridge RG, Schluter PJ, Spurling GK, Askew DA (2022) Ear and hearing health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 years and older: a scoping review. International Journal of Audiology 62(12), 1118-1128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Spurling GK, Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Hayman NE (2013) Implementing computerised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks in primary care for clinical care and research: a process evaluation. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 13, 108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Strange A, Johnson A, Ryan B, Yonovitz A (2008) The stigma of wearing hearing aids in an adolescent aboriginal population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology 30, 19-37.

| Google Scholar |

Villavisanis DF, Berson ER, Lauer AM, Cosetti MK, Schrode KM (2020) Sex-based differences in hearing loss: perspectives from non-clinical research to clinical outcomes. Otology & Neurotology 41, 290-298.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

World Health Organization (2021) World report on hearing. (WHO: Geneva) Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing [Accessed 25 March 2022]