Social media group support for antidepressant deprescribing: a mixed-methods survey of patient experiences

Amy Coe A * , Noor Abid

A * , Noor Abid  A and Catherine Kaylor-Hughes

A and Catherine Kaylor-Hughes  A

A

A

Abstract

Antidepressant use has continually increased in recent decades and although they are an effective treatment for moderate-to-severe depression, when there is no longer a clinical benefit, deprescribing should occur. Currently, routine deprescribing is not part of clinical practice and research shows that there has been an increase in antidepressant users seeking informal support online. This small scoping exercise used a mixed-methods online survey to investigate the motives antidepressant users have for joining social media deprescribing support groups, and what elements of the groups are most valuable to them.

Thirty members of two antidepressant deprescribing Facebook groups completed an online survey with quantitative and open-text response questions to determine participant characteristics and motivation for group membership. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, and open-text responses were analysed thematically through NVivo.

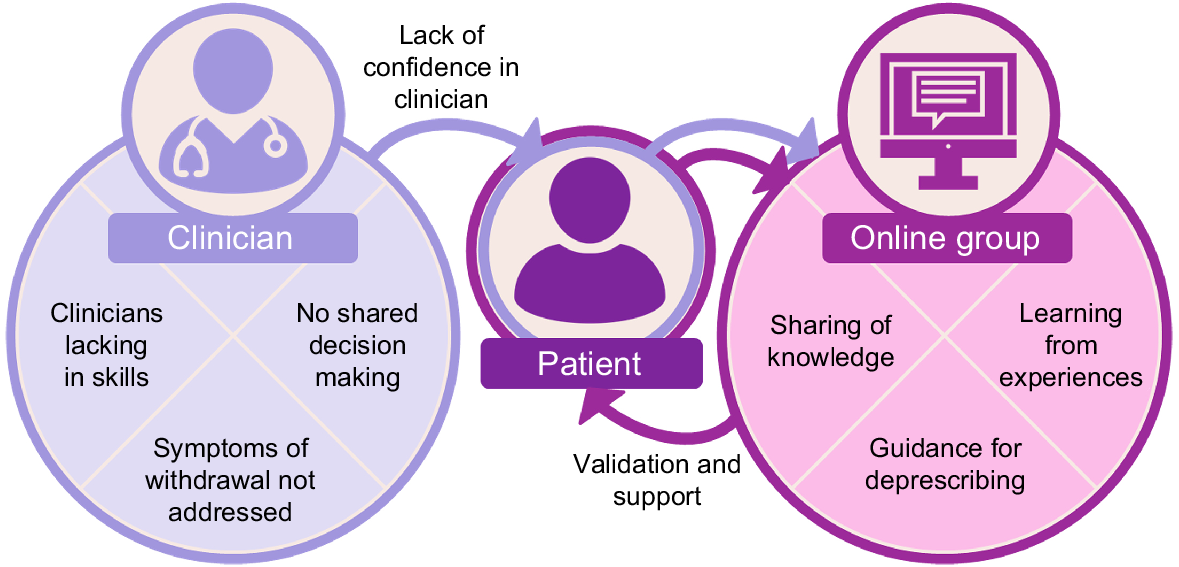

Two overarching themes were evident: first, clinician expertise, where participants repeatedly reported a perceived lack of skills around deprescribing by their clinician, not being included in shared decision-making about their treatment, and symptoms of withdrawal during deprescribing going unaddressed. Motivated by the lack of clinical support, peer support developed as the second theme. Here, people sought help online where they received education, knowledge sharing and lived experience guidance for tapering. The Facebook groups also provided validation and peer support, which motivated people to continue engaging with the group.

Antidepressant users who wish to cease their medication are increasingly subscribing to specialised online support groups due to the lack of information and support from clinicians. This study highlights the ongoing need for such support groups. Improved clinician understanding about the complexities of antidepressant deprescribing is needed to enable them to effectively engage in shared decision-making with their patients.

Keywords: antidepressant, clinician, deprescribing, experiences, online, patient, peer support, withdrawal.

Introduction

The rate of antidepressant prescriptions in Australia are among the highest in the world and is steadily increasing (OECD Statistics 2023). This trend is consistent with other developed countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) (Mojtabai and Olfson 2013; Bogowicz et al. 2021). Guidelines published by The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that individuals remain on antidepressants for 6–12 months following the cessation of depressive symptoms (Malhi et al. 2021; NICE 2022). However, evidence suggests that some individuals are continuing to be prescribed antidepressants for longer than the recommended duration (Cartwright et al. 2016). Prolonged use of antidepressant medications can result in various health concerns including an exacerbation of depressive symptoms, functional impairment and physical side-effects (Kelly et al. 2008; Ambresin et al. 2015; Ramic et al. 2020). Studies also suggest that anywhere between 30 and 50% of antidepressant users are continuing treatment without experiencing any clinical benefit (Ambresin et al. 2015; Davidson et al. 2020); therefore, deprescribing (the supervised and planned process of gradual dose reduction) may be necessary for some individuals.

Some antidepressant users have reported receiving little support from healthcare professionals when attempting to deprescribe (White et al. 2021; Read et al. 2023). In the past, clinicians have been criticised for mistaking withdrawal symptoms for relapse (Fava and Belaise 2018). Further, a recent review suggests that there is inadequate guidance for clinicians and patients when distinguishing withdrawal from relapse and managing withdrawal symptoms (Sørensen et al. 2022). Evidence-based information and research into antidepressant deprescribing is currently in its infancy (Gupta et al. 2019), with two trials underway in Australia (Coe et al. 2022; Kaylor-Hughes et al. 2023; Wallis et al. 2023a), one in the UK (Kendrick et al. 2020) and one in the Netherlands (Bot 2024). As such, a lack of information and support has led to patients recommencing antidepressant treatment or seeking other avenues for help (White et al. 2021; Read et al. 2023).

Online support groups may play a role in the supportive element of care for antidepressant users (Kendrick 2020). A recent study by White et al (2021) examined the role and utility of 13 Facebook groups dedicated to antidepressant withdrawal support (White et al. 2021). Group members reported that they found value in the support and knowledge offered from other members with lived experience, a finding that is reflected in specialised support groups on social media, in other illness domains (Scott et al. 2015; D’Agostino et al. 2017). In addition to peer support and community, multiple studies have proposed that the presence of online support platforms and the identification of oneself within these social groups has other benefits such as improving a member’s self-esteem and self-belief (McKenna and Bargh 1998; D’Agostino et al. 2017; Gage-Bouchard et al. 2017). Thus, there is use for social media to be a facilitator of support and information sharing between peers with lived experience.

The current study was used as a scoping exercise to investigate what motivates individuals to join online antidepressant deprescribing support groups and to determine which features of the group members find most valuable. This study aimed to contribute to the emerging research investigating the value of joining online antidepressant deprescribing support groups, which might then be applied to other areas of support for the deprescribing journey.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of a fourth-year honours biomedical student project (NA). Potential participants from two Facebook support groups (FG1; FG2, henceforth) were invited to take part in the study via expression of interest posts from the Facebook group administrators. Participants were able to click on a link to the survey if they wished to participate. Facebook was chosen as this social media platform allows for the formation of topic-specific, private groups. The selected Facebook groups were chosen due to their large number of members, as well as their primary ‘group aims’ being focussed on guidance and support for individuals who are attempting to deprescribe or reduce their antidepressant dose. At the time of recruitment, FG2 was exclusive to Facebook and had approximately 5000 members. FG1 has a presence as both a Facebook group with approximately 4000 members, as well as a web-based forum, with recruitment for this study taking place on both platforms. A third Facebook group with approximately 6000 members was initially approached to take part in the study; however, a response was only received after the survey had closed. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be aged >18 years and a member of FG1 and/or FG2.

Participants completed a short online survey via the Qualtrics online survey platform (https://www.qualtrics.com/au/) consisting of 34 multiple choice and nine open-response questions (see Supplementary Appendix A). Due to the time constraints of the student program, the survey was open for 4 weeks between July and August 2021.

Quantitative measures

Quantitative data were collected to characterise participants regarding their current depressive symptoms, beliefs about antidepressants and help-seeking tendencies. Depressive symptoms were measured using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al. 2003). The PHQ-2 is a brief two-item screening survey in which participants respond to two questions that indicate in the last 2 weeks, the presence or not, of depressive symptoms on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = None of the time to 3 = Nearly everyday). Total scores range from 0 to 6, with a cut-off score of ≥3 indicating the presence of depressive symptoms that warrant further investigation. Participant views on antidepressant medication were measured using the Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire – Antidepressants (BMQ; Horne et al. 1999). Participants respond to 18 questions such as ‘My medicine protects me from becoming worse’ on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly agree to 5 = Strongly disagree. The BMQ contains four subscales: (1) beliefs about the necessity of the medication (necessity; total score ranged from 5 to 25); (2) concerns about the negative effects of the medication (concerns; total scores ranged from 5 to 25); (3) concerns about the way doctors use medication (overuse; total scores ranged from 4 to 20), and; (4) beliefs that medications are harmful (harm; total scores ranged from 4 to 20). Higher scores indicate more negative views about antidepressant medication. Help-seeking was assessed using the General Help Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ; Wilson et al. 2005). Participants use a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely, to rate the likelihood of them seeking help from a list of potential resources for problems with suicidal ideations and personal or emotional problems. Higher scores indicate higher intention to seek help from the listed source.

Open response questions

Participants were asked to describe their experiences of deprescribing and motivations for joining Facebook support groups. There was no limit placed on length of responses. As this was a scoping study, data saturation was not the goal of open-text data collection. Additionally, saturation of text responses is not considered to be useful when conducting thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2021). The open response questions were designed by the authors specifically for the current study (see Supplementary Appendix A).

Data analysis

Upon survey closure, the quantitative data were downloaded and imported to STATA (ver. 17, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and descriptive statistics were calculated. Open response data were entered in NVivo (ver. 12, QSR International, https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home) and analysed using reflective analysis and an inductive (data-driven) approach to incorporate the experiences and perspectives of multiple patients to help identify recurring themes (Braun and Clarke 2006). Each line of a participant’s response was subject to coding. NA read and re-read each response and made notes about any patterns found in the data. AC read and re-read all responses and made independent notes about the data. Patterns were then discussed between NA, CKH and AC, which then formed the basis for initial coding. An initial coding framework was developed and altered as analysis progressed. All responses were coded by NA and independently double coded by AC. No coding discrepancies were found between authors. Once initial coding was completed, potential themes and subthemes were discussed and approved by all authors.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of The University of Melbourne (HREC No. 21870). Participants were advised that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. Due to the financial constraints of the student Honours program, compensation for participants was not provided.

Results

A total of 37 individuals clicked the link to the survey, and 30 (81%) consented to participate. All 30 participants provided demographic details (see Table 1), 26 (87%) completed the quantitative measures, and 26 (87%) provided open text responses, with 21 completing both the quantitative and open response questions. Responses to the open questions ranged from 1 to 10 sentences. Most participants were female (n = 19; 63.3%). Participants were aged ≥18 years, with the most common age range (n = 15; 50%) being 46–50+ years. The majority (n = 22, 73.3%) of members reported being first diagnosed with depression ≥4 years prior to the commencement of the study. More than half (n = 16; 53.3%) stated that they had been prescribed their current antidepressant medication for >4 years. Seventeen participants (56.7%) reported experiencing withdrawal symptoms when abruptly ceasing or tapering their antidepressant medication (see Supplementary Appendix B). The four most common effects reported by participants were experiences of insomnia (70%; n = 12), dizziness (52%; n = 9), anxiety (52%; n = 9) and increased feelings of pain in the body (47%; n = 8).

| n | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 19 | 63.3 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–25 | 1 | 3.3 | |

| 26–35 | 9 | 30.0 | |

| 36–45 | 5 | 16.6 | |

| 46–50+ | 15 | 50.0 | |

| Country of residence | |||

| United States | 8 | 26.6 | |

| Australia | 6 | 20.0 | |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 16.6 | |

| Netherlands | 2 | 6.6 | |

| Germany | 2 | 6.6 | |

| Austria | 2 | 6.6 | |

| OtherA | 5 | 16.6 | |

| First depression diagnosis | |||

| <12–24 months | 6 | 20. | |

| 2–4 years | 2 | 6.6 | |

| 4–5+ years | 22 | 73.3 | |

| Length of antidepressant treatment | |||

| 24 months | 8 | 26.6 | |

| 2–4 years | 6 | 20 | |

| 4–5+ years | 16 | 53.3 | |

| Group membership | |||

| FG1 | 19 | 63.3 | |

| FG2 | 11 | 36.6 | |

| Group membership duration | |||

| 0–12 months | 13 | 43.3 | |

| 1–3+ years | 17 | 56.7 | |

| Level of group involvement | |||

| Active participant | 10 | 33.3 | |

| Occasionally active | 16 | 53.3 | |

| Observer | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 3.3 | |

| M | s.d. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-2) | 2.3 | 2.1 | |

| Necessity of antidepressants (BMQ) | 20.12 | 4.75 | |

| Concerns about antidepressants (BMQ) | 10.12 | 4.9 | |

| Antidepressants are overused (MBQ) | 7.12 | 3.63 | |

| Antidepressants are harmful (BMQ) | 10.91 | 3.76 |

PHQ-2, patient health questionnaire 2-item (Kroenke et al. 2003); BMQ, beliefs about medicines – antidepressants (Horne et al. 1999).

Group members primarily resided in the US, Australia and the UK. The majority (n = 19; 63.3%) of individuals were members of FG1. Most participants reported contributing to their group in some capacity (e.g. posting questions or responding to other group members), with 33.3% (n = 10) denoting that they were an active participant and 53.3% (n = 16) reporting that they were an occasionally active participant.

Mean scores on the PHQ-2 indicated the presence of none to low depressive symptoms (M = 2.3, s.d. = 2.1). Most respondents held somewhat negative beliefs about their antidepressants, with many believing that antidepressant medications were unnecessary to recover from their depression (M = 20.12, s.d. = 4.75). Participants were also concerned about the negative effects of their medication (M = 10.12, s.d. = 4.9), the way doctors prescribe antidepressants (M = 7.12, s.d. = 3.63) and believed that antidepressants cause harm (M = 10.91, s.d. = 3.76). Results from the GHSQ indicated that participants were more likely to seek help for personal–emotional problems from their partners, friends or mental health professionals. When seeking help for suicidal thoughts, individuals were most likely to seek help from mental health professionals and friends. See Supplementary Appendix C for the full table of help-seeking responses.

Qualitative outcomes: motivations for joining online support groups for antidepressant deprescribing

In the open-ended text response portion of the online survey, participants reported a variety of motives for joining Facebook groups dedicated to antidepressant deprescribing, which are captured by two overarching themes: (1) clinician expertise; and (2) peer support through education validation and shared experiences.

Clinician expertise

Participants acknowledged that clinicians do not have appropriate guidelines or education to support patients to deprescribe and this led many to seek help through online peer support. Subsequently, participants felt less confident in their general practitioner (GP) and/or clinician when guiding them through the deprescribing process. One participant reported:

GP & psychiatrist don’t know how to get you off these drugs safely. Psychiatrist said do one week at half dose then stop. I tried that twice. Got terrible insomnia, saw I was headed to very dark place & successfully reinstated immediately. Psychiatrist then said, and I quote “I don’t know then” about how to get me off. GP similarly bad. First suggested skipping days. I said no. [GP] suggested cutting by 1/3 every 3 weeks – I said no I wanted to do 10% reductions of current dose. Too scared he’d say no to taper I didn’t tell him [I was tapering]. (Female, aged 36–45 years, FG2, UK)

Confidence in clinicians was also reduced when participants had experienced a lack of acknowledgement from their doctor regarding the existence of withdrawal symptoms. Some participants reported experiencing clinicians mistaking withdrawal symptoms for relapse and that their experiences of withdrawal were not believed to be associated with deprescribing from antidepressants. Several participants were of the belief that healthcare professionals are yet to acknowledge the existence of withdrawal. One participant reported:

99% of all medical providers do not acknowledge withdrawal from antidepressants. They don’t believe these medications can cause severe, life threatening and long-lasting withdrawal. They do not want to educate themself about this topic, because they do not learn about it in their training. (Male, aged 26–35 years, FG2, Germany)

It was often remarked that medical practitioners prescribe antidepressants somewhat prematurely and some participants felt as though their depressive symptoms could have been managed by talking therapy or by considering current lifestyle factors that could be contributing to their depressive symptoms prior to prescribing medications. One participant wrote:

It was 8 months after my first baby, and I had a stressful job. He should have considered the idea of hormonal changes or referred me to a talking therapy (though waiting lists would probably have been too long where I live). He knew I wasn’t keen on ADs but gave no alternatives. As part of my condition was upset stomachs, a referral to a dietician or a test for food sensitivities could have been talked about. (Female, aged 46–50+ years, FG1, UK)

Some participants also reported that their clinicians were unable to provide them with sufficient information regarding the possible side-effects associated with antidepressant use. One participant reported:

No word on possible withdrawal or heavy side effects. Just the usual “it’s a safe medication and you can stop whenever you want, don’t worry”. (Male, aged 26–35 years, FG2, Germany)

Peer support through education, validation and shared experiences

Participants were overwhelmingly positive about their experiences of online support groups. This was mainly due to participants having the opportunity to receive support and obtain additional information about antidepressant use, tapering and withdrawal symptoms. One participant said:

It has been helpful in a myriad of ways. As a way of education in how traditional tapering strategies are bound to fail and what comprises a harm reduction approach in tapering. Best of all, you get in contact with peers that are in the same boat with whom one can share experiences. (Male, aged 36–45 years, FG2, Netherlands)

The sharing and validation of experiences naturally created a sense of community where participants felt that help-seeking also led to receiving empathy and understanding from their peers.

I literally owe my life to the Facebook group. It was there that I learned why I was experiencing such bad withdrawals and how I could taper to make the process survivable. And the emotional support and companionship with others who truly understand is how I got through the hardest times. (Female, aged 26–35 years, FG1, USA)

Participants highlighted the value of the accessibility to resources and deprescribing protocols successfully used by others. These deprescribing protocols had been used by others who had similarly experienced difficulties adhering to the traditional deprescribing protocols. Some respondents reported that they had successfully deprescribed from their medications as a result of the information obtained from their online support group. One participant wrote:

The people on these forums understand what happens in withdrawal and will give you appropriate guidelines to go by. There are thousands of people like myself seeking guidance from these places. (Female, aged 36–45 years, FG2, Australia)

A model showing the engagement process of antidepressant users when joining an online support group and their subsequent continued engagement with these support groups on Facebook, is shown in Fig. 1. The antidepressant user is situated in the middle, between the clinician and their online supportgroup. A lack of confidence in clinician skills acts as the initial driver for antidepressant users to seek help from online peer groups. Support, information and validation act as motivators for improving confidence in deprescribing within the groups.

Discussion

This scoping study investigated the motivations of antidepressant users seeking support from social media groups for antidepressant deprescribing. It found that antidepressant users perceived that clinician education and knowledge is lacking with respect to their ability to appropriately deprescribe medications, as well as their ability to support the process of deprescribing when it is appropriate to do so. Clinician education has become a recent focus in the wider deprescribing literature to support routine deprescribing in practice, in a manner that is representative of the real-life challenges faced by patients (Coe et al. 2021; Isenor et al. 2021; Horowitz and Taylor 2024). Clinicians also welcome the prospect of additional training in order to adequately support the deprescribing efforts of their patients (Bowers et al. 2019).

As a result of the lack of clinician-led information, patients appear to be educating themselves about their medication, as well as seeking alternative deprescribing protocols through online social media, in line with findings by White et al. (2021). In addition, the quantitative and open text response data indicated that participants were concerned that there was an over-reliance by clinicians to prescribe antidepressants for depressive disorders when alternative treatments may be just as effective or preferrable. These perceptions of potential medical overtreatment match those found in previous studies (Pestello and Davis-Berman 2008; Gibson et al. 2014).

The motivations individuals appear to have when joining an online antidepressant support group primarily stem from their need for support and guidance while managing symptoms of withdrawal. Many participants reported feeling a lack of trust from their general practitioner and often felt that the withdrawal symptoms they experienced were a result of ‘unrealistic’ and ‘harmful’ deprescribing protocols. Thus, the acknowledgement of symptoms and shared experiences of others serves to be a welcome factor within social media-based support groups. The sense of community and peer support formed within these groups provides an element of care that seemingly makes the practice of deprescribing easier. Furthermore, there appeared to be greater compliance with the tapering strategies suggested by these groups when compared with those suggested by medical professionals. Although these strategies are based on patient experiences, caution should be exercised when consuming such information as it is generally disseminated by non-expert peers and has the potential to be misleading or harmful.

It is worth considering that potential differences in healthcare training and funding models could impact patients’ perceptions and experiences of deprescribing with their clinician. GPs are the first port of call for mental health help-seeking and they prescribe the majority of antidepressants globally (Britt et al. 2016; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022). However, there may be differences in GP training, insurance payouts and patient billing, which may contribute to the lack of knowledge, skills or capacity to adequately support deprescribing in practice. Some countries have also integrated specialised mental health practices into their clinics. For example, the Netherlands have a nurse practitioner model where nurses provide mental health care including antidepressant deprescribing support (Wallis et al. 2023b), potentially resulting in lower prescribing rates and higher patient satisfaction. However, participant views in the current study remained largely similar, regardless of their country of origin, suggesting that the lack of antidepressant deprescribing knowledge by clinicians is a global issue.

Although participants were emphatic about the helpfulness of their Facebook support group, the results from the GHSQ indicated that online support groups were not the first port of call when seeking help. This could suggest that factors such as desperation and frustration at the current antidepressant deprescribing standards prompt individuals to join online deprescribing groups. The presence of individuals with shared experiences makes these groups a viable option for members who feel as though they did not receive adequate care from their medical professional. Many group members faced similar challenges and it is this sense of camaraderie that seemingly supports members through their deprescribing journey. These viewpoints indicate that a motive for subscribing to online groups stems from the need for empathy and understanding. For some, these elements appear to be lacking in a clinical setting. Consistent with a 2016 study that proposed that a reluctance to use formal healthcare services may exist for many in need of mental health care, the treatment efforts of participants may be encouraged through online peer support (Naslund et al. 2016).

The extent to which withdrawal symptoms contributed to the motivation for joining specialised social media support groups was somewhat expected (White et al. 2021), but continues to highlight the experiences of antidepressant users. Research suggests that 61% of people who attempt deprescribing experience withdrawal effects, with 44% reporting those effects as severe (Read 2020). A systematic review also found that up to 86% of people experience withdrawal symptoms that may last up to 79 weeks (Davies and Read 2019). Historically, withdrawal symptoms have been attributed to relapse due to a similarity in symptoms and there has been a reported lack of knowledge in reliably distinguishing between the two (Read 2020). This may indicate why clinicians are not able to support people with their withdrawal symptoms and, in turn, lead to patients seeking online peer support. However, withdrawal symptoms and relapse are distinguishable (Horowitz and Taylor 2022) and recently have been recognised by The Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2019) and the NICE Guidelines (Iacobucci 2019). Withdrawal symptoms should be prioritised in future clinical training and patient information, given its prevalence as a key area of concern for patients and GPs alike (Davies and Read 2019; Read 2020).

Strengths and limitations

This study provides valuable insights into many of the core problems associated with unnecessary antidepressant use and the motivating factors for people to seek help away from the clinical environment. Certain limitations should be considered when examining the results of this research. This was a small study with a total of 30 participants, with the majority of participants (63.3%) being members from one group. Participants may have been exposed to common sentiments held within a particular group, which potentially could have influenced responses. Our study attempted to mitigate the degree of response bias by selecting social media groups that were relatively inclusive in their entry requirements. Other groups with a larger membership base were available; however, their ‘group aims’ often stated that members sharing positive posts about medications would be rejected. As such, these groups were not considered as they were likely to be more partial in their views. The groups that were selected for the study were not restricted to a specific class of antidepressant, as is common for groups of this nature. The FG1 group was inclusive to antidepressant users of all classes, whereas the FG2 group primarily provided support for users prescribed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Thus, the motives and viewpoints of participants were derived from individuals using various antidepressant medicines. The results of this study cannot be generalised to be applicable for social media platforms as a whole, but rather only the networks from which the responses were obtained.

Future research and implications for practice

Although the current study looked to provide a brief investigation of why antidepressant users join online support groups, findings suggest that further and more in-depth information about the antidepressant user experience of participants in these groups is warranted with larger sample sizes. This may allow for generalisability and/or a capture of the experiences of group members who report being less active in the group. In this way, a larger sample size would provide a more holistic picture of the motivations, benefits and potential harms of group membership. Respondents also held somewhat negative beliefs about antidepressants. Qualitative investigation of the origins of these beliefs and their impacts on the doctor–patient relationship and deprescribing success could help inform a deprescribing process in practice. The low depressive symptoms reported by the current sample suggests that antidepressant deprescribing would be appropriate. Future research should investigate how to best identify patients ready for deprescribing and what steps are required to initiate a supported deprescribing process, using moderated peer support as an adjunct to clinical care. There is also a need to implement these suggestions into clinical practice to repair the doctor–patient relationship and re-build patient confidence in their clinician. This would require GPs to engage in evidence-based training focused on identifying, informing and supporting patients through withdrawal. It would be imperative that the lived experience perspective inform revisions to clinician training and any revisions made to current antidepressant deprescribing guidelines to acknowledge and alleviate symptoms of withdrawal.

Conclusion

Antidepressant prescribing rates are growing, and individuals are increasingly turning to social media for deprescribing information and support due to a perceived lack of support by healthcare professionals. Antidepressant users who may be seeking information or who are ready to deprescribe report that Facebook antidepressant withdrawal support groups are a major source of help for their withdrawal symptoms.

Data availability

All authors had complete access to the raw and analysed study data at all points during the study. Access will be ongoing for the remainder of the approved ethics period (5 years) and these data are stored in line with The University of Melbourne data storage policy.

Declaration of funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study. AC and NA drafted the manuscript. CKH revised early drafts and all authors revised later drafts. All authors developed the initial themes. NA completed the initial qualitative coding and AC double coded the qualitative data. All results were discussed and approved by all authors. The model was developed by AC.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the 30 participants from the two Facebook support groups for sharing their experiences and making this research possible. The authors wish to also thank the moderators of the Facebook groups for their support and providing access to their members.

References

Ambresin G, Palmer V, Densley K, Dowrick C, Gilchrist G, Gunn JM (2015) What factors influence long-term antidepressant use in primary care? Findings from the Australian diamond cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders 176, 125-132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Australia’s health 2022: data insights, catalogue number AUS 240, Australia’s health series number 18. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, ACT, Australia) Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2022-data-insights/about

Bogowicz P, Curtis HJ, Walker AJ, Cowen P, Geddes J, Goldacre B (2021) Trends and variation in antidepressant prescribing in English primary care: a retrospective longitudinal study. BJGP Open 5(4), BJGPO.2021.0020.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bot M (2024) Optimal, PERsonal Antidepressant use. The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Available at https://opera-project.nl/

Bowers HM, Williams SJ, Geraghty AWA, Maund E, O’brien W, Leydon G, May CR, Kendrick T (2019) Helping people discontinue long-term antidepressants: views of health professionals in UK primary care. BMJ Open 9, e027837.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13(2), 201-216.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cartwright C, Gibson K, Read J, Cowan O, Dehar T (2016) Long-term antidepressant use: patient perspectives of benefits and adverse effects. Patient Preference and Adherence 10, 1401-1407.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coe A, Kaylor-Hughes C, Fletcher S, Murray E, Gunn J (2021) Deprescribing intervention activities mapped to guiding principles for use in general practice: a scoping review. BMJ Open 11(9), e052547.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Coe A, Gunn J, Kaylor-Hughes C (2022) General practice patients’ experiences and perceptions of the WiserAD structured web-based support tool for antidepressant deprescribing: protocol for a mixed methods case study with realist evaluation. JMIR Research Protocols 11(12), e42526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

D’Agostino AR, Optican AR, Sowles SJ, Krauss MJ, Escobar Lee K, Cavazos-Rehg PA (2017) Social networking online to recover from opioid use disorder: a study of community interactions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 181, 5-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Davidson SK, Romaniuk H, Chondros P, Dowrick C, Pirkis J, Herrman H, Fletcher S, Gunn J (2020) Antidepressant treatment for primary care patients with depressive symptoms: data from the diamond longitudinal cohort study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 54, 367-381.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Davies J, Read J (2019) A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: are guidelines evidence-based? Addictive Behaviors 97, 111-121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fava GA, Belaise C (2018) Discontinuing antidepressant drugs: lesson from a failed trial and extensive clinical experience. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 87(5), 257-267.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gage-Bouchard EA, LaValley S, Mollica M, Beaupin LK (2017) Cancer communication on social media: examining how cancer caregivers use Facebook for cancer-related communication. Cancer Nursing 40(4), 332-338.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gibson K, Cartwright C, Read J (2014) Patient-centered perspectives on antidepressant use: a narrative review. International Journal of Mental Health 43(1), 81-99.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M (1999) The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychology & Health 14, 1-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Horowitz MA, Taylor D (2022) Distinguishing relapse from antidepressant withdrawal: clinical practice and antidepressant discontinuation studies. BJPsych Advances 28(5), 297-311.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Iacobucci G (2019) NICE updates antidepressant guidelines to reflect severity and length of withdrawal symptoms. BMJ 367, l6103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Isenor JE, Bai I, Cormier R, Helwig M, Reeve E, Whelan AM, Burgess S, Martin-Misener R, Kennie-Kaulbach N (2021) Deprescribing interventions in primary health care mapped to the behaviour change wheel: a scoping review. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 17, 1229-1241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kaylor-Hughes C, Coe A, Fletcher S, Chondros P, Chatterton ML, Hoyer D, Chen TF, Ng C, Mangin D, Allnutt Z, Densley K, Kendrick T, Gunn J (2023) WiserAD: the effect of a structured online intervention on antidepressant deprescribing in primary care. Available at https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=383739&isReview=true

Kelly K, Posternak M, Jonathan EA (2008) Toward achieving optimal response: understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 10(4), 409-418.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kendrick T, Geraghty AWA, Bowers H, Stuart B, Leydon G, May C, Yao G, O’Brien W, Glowacka M, Holley S, Williams S, Zhu S, Dewar-Haggart R, Palmer B, Bell M, Collinson S, Fry I, Lewis G, Griffiths G, Gilbody S, Moncrieff J, Moore M, Macleod U, Little P, Dowrick C (2020) REDUCE (reviewing long-term antidepressant use by careful monitoring in everyday practice) internet and telephone support to people coming off long-term antidepressants: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 21(1), 419.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2003) The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care 41(11), 1284-1292.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Malhi GS, Bell E, Bassett D, Boyce P, Bryant R, Hazell P, Hopwood M, Lyndon B, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh AB, Murray G (2021) The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 55(1), 7-117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McKenna KYA, Bargh JA (1998) Coming out in the age of the Internet: identity “demarginalization” through virtual group participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75(3), 681-694.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mojtabai R, Olfson M (2013) National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 75(2), 169-177.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, Bartels SJ (2016) The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 25(2), 113-122.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

NICE (2022) Depression in adults: treatment and management. p. 103. (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222/resources/depression-in-adults-treatment-and-management-pdf-66143832307909

OECD Statistics (2023) Pharmaceutical market – full dataset [dataset]. (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Available at https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?datasetcode=health_phmc

Pestello FG, Davis-Berman J (2008) Taking anti-depressant medication: a qualitative examination of internet postings. Journal of Mental Health 17(4), 349-360.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ramic E, Prasko S, Gavran L, Spahic E (2020) Assessment of the antidepressant side effects occurrence in patients treated in primary care. Materia Socio-Medica 32(2), 131-134.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Read J (2020) How common and severe are six withdrawal effects from, and addiction to, antidepressants? The experiences of a large international sample of patients. Addictive Behaviors 102, 106157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Read J, Moncrieff J, Horowitz MA (2023) Designing withdrawal support services for antidepressant users: patients’ views on existing services and what they really need. Journal of Psychiatric Research 161, 298-306.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, Gnjidic D, Del Mar CB, Roughead EE, Page A, Jansen J, Martin JH (2015) Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(5), 827-834.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sørensen A, Jørgensen KJ, Munkholm K (2022) Description of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms in clinical practice guidelines on depression: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 316, 177-186.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wallis KA, Donald M, Horowitz M, Moncrieff J, Ware RS, Byrnes J, Thrift K, Cleetus MA, Panahi I, Zwar N, Morgan M, Freeman C, Scott I (2023a) RELEASE (REdressing Long-tErm Antidepressant uSE): protocol for a 3-arm pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial effectiveness-implementation hybrid type-1 in general practice. Trials 24(1), 615.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wallis KA, Dikken PJS, Sooriyaarachchi P, Bohnen AM, Donald M (2023b) Lessons from the Netherlands for Australia: cross-country comparison of trends in antidepressant dispensing 2013–2021 and contextual factors influencing prescribing. Australian Journal of Primary Health 30, PY23168.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

White E, Read J, Julo S (2021) The role of Facebook groups in the management and raising of awareness of antidepressant withdrawal: is social media filling the void left by health services? Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 11, 204512532098117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi JV, Rickwood D (2005) Measuring help seeking intentions: properties of the general help seeking questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling 39(1), 15–-28.

| Google Scholar |