GP perspectives on a psychiatry phone line in Western Australia’s Great Southern region: implications for addressing rural GP workload

Beatriz Cuesta-Briand A * , Daniel Rock B C D , Layale Tayba E , James Hoimes F , Hanh Ngo A , Michael Taran E and Mathew Coleman A E F G

A * , Daniel Rock B C D , Layale Tayba E , James Hoimes F , Hanh Ngo A , Michael Taran E and Mathew Coleman A E F G

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

Mental illness is a public health challenge disproportionately affecting rural Australians. GPs provide most of the mental health care, and they report increasing levels of burnout and unsustainable workload in the context of increased patient complexity. This may be more salient in rural settings characterised by resource constraints. In this paper, we use evaluation data from a GP psychiatry phone line established in Western Australia’s Great Southern region in 2021 to describe GPs’ perspectives on the service and reflect on how it may help alleviate rural GP workload.

The sample was recruited among GPs practicing in the region. Data were collected through an online survey and semistructured interviews. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the survey data. Interview data were subjected to thematic analysis; qualitative survey data were used for triangulation.

A total of 45 GPs completed the survey and 14 were interviewed. Interview data yielded three themes: the criticality of timeliness; the building blocks of confidence; and trust. GPs were highly satisfied with the service, and timeliness and trust were the characteristics underpinning its effectiveness. The service built GPs’ confidence in managing mental health and alcohol and other drug use issues through strengthening knowledge and providing reassurance.

Our results suggest that a telephone line operated by trusted, local psychiatrists with knowledge of the local mental health ecosystem of support can reduce rural GP workload through building confidence and strengthening personal agency, helping GPs navigate the ethical and clinical labyrinth of managing patient complexity in rural settings.

Keywords: evaluation, GP workload, patient complexity, primary care, psychiatry advice service, psychiatry phone line, rural adversity, rural mental health.

Introduction

Mental ill health is one of the great public health challenges of our time. Its burden has been amplified by COVID-19, with evidence (AIHW 2022; Aknin et al. 2022) showing increased levels of psychological distress during the pandemic. Unprecedented weather events, such as bushfires and recurrent floods, have also been important drivers of mental health problems, including ‘eco-anxiety’ (Patrick et al. 2023). In Australia, the prevalence of mental illness is higher in rural areas, with those living in inner regional areas twice as likely, and those living in outer regional and remote areas almost three times as likely, to report a mental health condition compared with their urban counterparts (6.8% and 9.5%, respectively, compared with 3.4%; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022).

General practitioners (GPs) provide most of the mental health care, including first-line treatment and referral to specialist services if required. The GP role in mental health care has increased over the past decades, and mental health-related issues represented 12.4% of all general practice presentations in 2015–2016, up from 10.8% in 2007–2008 (Britt et al. 2016). The impact of COVID-19 and recurrent extreme weather events has only added to this trend, with recent figures showing that 38% of GP consultations incorporated a mental health component (RACGP 2022).

Given the increasing prevalence of multimorbidity and complex multimorbidity (Koné Pefoyo et al. 2015; Harrison et al. 2016), GPs may experience an emotional burden associated with feelings of powerlessness linked to patient characteristics, including social, psychiatric and disease factors (Braillard et al. 2018). This burden is greater when GPs are faced with ‘multimorbidity plus’; that is, multimorbidity plus social complexity (McCallum and MacDonald 2021).

In Australia, GP reports of burnout and unsustainable workload have been increasing over the past few years (Wieland et al. 2021; Hoffman et al. 2023). These issues may be especially salient in rural areas where specialist services are scarce or non-existent, and evidence shows that regional GPs are more likely to report feeling isolated and occupational stress arising from lack of resources, including access to services (Clough et al. 2020).

One way in which GPs can be supported to manage their patients’ mental health issues is through telephone psychiatry advice services. International evidence shows that telephone specialist consultation services – including psychiatry services – are highly valued by GPs, and that accessing them results in reduced unnecessary referrals and emergency department presentations (Wilson et al. 2016; Tian et al. 2021).

In Australia, a government-funded national GP-Psych Support service was implemented in 2004, offering specialist mental health care advice to GPs via phone, fax or email (Bradstock et al. 2005). The service was managed by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and delivered by a private provider; it was in operation until late 2013, when it was discontinued due to low use and high cost per call (Productivity Commission 2021). In 2018, a GP Psychiatry Support Line, funded through local Primary Health Networks and also privately operated, was established in New South Wales, and later expanded to Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory (Productivity Commission 2021).

Findings from an evaluation of a local pilot program in the Hunter Valley (Sankaranarayanan et al. 2010), and limited initial evidence on the GP-Psych Support service (Bradstock et al. 2005) support international evidence. However, the published Australian evidence is scarce, and questions remain on the ongoing sustainability of this service model.

The GP Psychiatry Phone Line (GPPPL) was established to fill a mental health service gap in Western Australia’s (WA) Great Southern region, with increasing referrals and longer wait times for the local public health service despite an uptick in telehealth during the pandemic, and limited availability of private specialist psychiatry (WA Country Health Service 2021; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). The design of the GPPPL was informed by the lessons gleaned from previous similar services relating to sustainability and service delivery model issues, and was developed in consultation with regional GPs and practice managers.

The GPPPL was evaluated to assess its effectiveness at supporting GPs, enhancing mental health primary care for patients and improving workflow efficiency for mental health providers. In this paper, we use GPPPL evaluation data to describe GPs’ perspectives on the GPPPL, and reflect on how such a service may help alleviate GP workload in a rural setting.

Methods

Context

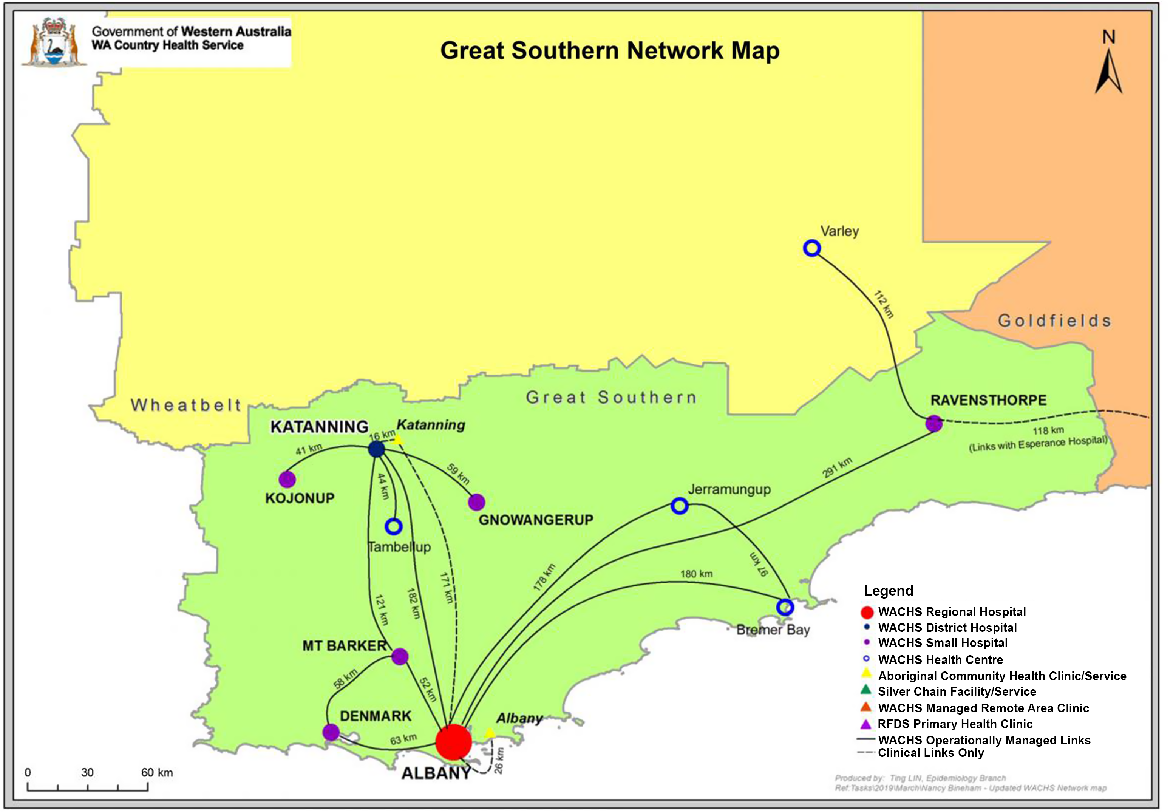

The Great Southern region is located on the south coast of WA; it has an area of 39 007 km2 and a population of approximately 64 000 people. Its main administrative centre, Albany, is located 418 km from Perth and has a population of approximately 38 000 people (WA Country Health Service 2021). As seen in Fig. 1, the regional hospital is located in Albany, and there is one district hospital and four small hospitals (WA Country Health Service 2021). The only public specialist mental health service is in Albany. There are 100 GPs (Western Australian General Practice Education and Training 2022) and five psychiatrists practicing in a region where mental health issues account for the greatest burden of disease (19.4% of the total; DHWA 2021).

Service

Established in partnership with the WA Primary Health Alliance, the GPPPL began operating in February 2021. The service aims to support GPs practicing in the Great Southern in managing high-prevalence mental health conditions (e.g. depression, anxiety), and alcohol and other drug (AOD) presentations, while streamlining access to specialist and acute services for more complex cases if required. The GPPPL provides GPs with telephone access to a local psychiatrist for treatment, and management advice in real time and with the patient present, if indicated. The service does not act as a referral pathway, and clinical care and governance for patient care remains with the GP.

The service is accessible via a mobile phone number from Monday to Friday (08:30–18:00). GPs contacting the GPPPL after hours can leave a message and the call is returned the next business day. The calls are managed by psychiatrists from the Great Southern Mental Health Service (GSMHS) based in Albany.

Evaluation

This paper reports on results from a broader evaluation of the GPPPL conducted after its first year of operation. The evaluation adopted a mixed-methods approach to assess the impact of the GPPPL on GPs, patients and the GSMHS, and to identify barriers and facilitators to using the service from a GP perspective. Ethics approval was granted by the WA Country Health Service.

Data collection

Data presented here pertain to GP perspectives and were collected through an online survey aimed at gathering the views of a broad range of GPs, and semistructured interviews designed to explore the survey topics in depth. The perspectives of GPPPL non-users were sought to identify potential barriers to using the service.

A link to a brief online survey was emailed to all GPs practicing in the region via the WA Primary Health Alliance in February and March 2022. The non-validated survey was piloted, and the content was aligned with the aims of the GPPPL: Likert scale questions were designed to measure the impact of the GPPPL on perceived knowledge, skills and confidence in managing mental health and AOD issues, and an open-ended question was designed to identify barriers and facilitators to engaging with the GPPPL and provide additional comments (see supplementary materials). Information about the evaluation was provided, and consent was implied by completing the survey. The survey was anonymous; all data were hosted within the Qualtrics environment and accessible to the research team only.

GPs practicing in the Great Southern region were invited to participate in an interview via an invitation letter emailed in February 2022. A non-probability sampling technique was adopted, including self-selection and purposive sampling designed to include diverse perspectives (GPPPL users and non-users, GP Fellows and Registrars, and a range of practices and locations). Data saturation was deemed to have been reached after several rounds of invitations. The interview schedule explored the following topics: perceived impact on confidence, knowledge and skills in managing mental health and AOD issues; perceived barriers to accessing the service; and overall experience and satisfaction with the GPPPL (see supplementary materials). Consent was obtained in writing prior to the interview. Interviews were audiorecorded.

Data analysis

Quantitative survey data were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis. The interview audio files were transcribed verbatim, and the resulting transcripts were imported into NVivo (QSR International 2021) and thematically analysed following these steps: immersion in the data; coding; category formation; and identification of themes (Green et al. 2007). Coding and category formation were largely inductive, and the exploration of the notion of ‘complexity’ drew from the literature on GP emotional burden associated with patient complexity (Braillard et al. 2018; McCallum and MacDonald 2021). All authors except HN read the transcripts; BCB performed the initial coding; initial themes were identified by BCB, DR and MC, then refined until consensus was reached among all authors except HN, who did not participate in the qualitative data analysis. Qualitative data from the survey were subjected to content analysis and used to triangulate the interview data.

Results

Sample

A total of 45 GPs took part in the survey; this represents 45.0% of all GPs practicing in the region (Western Australian General Practice Education and Training 2022). As seen in Table 1, our sample included 30 GP Fellows and 15 GP Registrars, representing 36.7% and 83.3%, respectively, of all GP Fellows and Registrars in the region (Rural Health West 2023).

| Characteristic | Participants, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPPPL user | Yes | 42 (93.3) | |

| No | 3 (6.7) | ||

| Qualifications | GP Fellow | 30 (66.7) | |

| GP Registrar (trainee) | 15 (33.3) | ||

| No. of calls to the GPPPL | 0 | 3 (6.7) | |

| 1–5 | 23 (51.1) | ||

| 6–10 | 12 (26.7) | ||

| ≥10 | 7 (15.6) |

A total of 14 semistructured interviews were conducted. The sample included a range of participants in terms of years of practice and practice location (see Table 2).

| Characteristic | Participants, n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPPPL user | Yes | 13 (92.9) | |

| No | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Qualifications | GP Fellow | 10 (71.4) | |

| GP Registrar (trainee) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| Years of GP practice | 0–4 | 5 (35.7) | |

| 5–9 | 3 (21.4) | ||

| 10–19 | 3 (21.4) | ||

| 20–29 | 1 (7.1) | ||

| ≥30 | 2 (14.3) | ||

| Years of practice in Great Southern | 0–4 | 7 (50.0) | |

| 5–9 | 1 (7.1) | ||

| 10–19 | 3 (21.4) | ||

| 20–29 | 2 (14.3) | ||

| ≥30 | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Location | Albany (MM 3) A | 6 (42.9) | |

| Other (MM 5) A | 8 (57.1) |

Survey results and impact on referrals

A high level of satisfaction about the GPPPL was observed among those who had used the line (n = 42). As seen in Table 3, there was a very strong level of agreement on overall statements regarding timeliness, satisfaction with the advice received and satisfaction with the service.

| Domain and statement | Strongly agree, n (%) | Somewhat agree, n (%) | Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | Somewhat disagree, n (%) | Strongly disagree, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived increased knowledge and skills on individual patient management | ||||||

| The advice I received increased my knowledge of mental health issues | 29 (69.0) | 11 (26.2) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| The advice I received increased my skills in managing my patients’ mental health issues | 32 (76.2) | 8 (19.0) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Perceived increased knowledge and skills overall | ||||||

| The advice received through the GPPPL has increased my knowledge on mental health issues and AOD issues | 20 (47.6) | 14 (33.3) | 8 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| The advice received through the GPPPL has increased my clinical skills in managing mental health and AOD issues (n = 41) | 27 (65.9) | 7 (17.1) | 6 (14.6) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Perceived increased confidence on individual patient management | ||||||

| I felt more confident in managing my patients’ mental health issues as a result of the advice I received | 32 (76.2) | 9 (21.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Perceived increased confidence overall | ||||||

| The advice received through the GPPPL has increased my confidence in managing mental health and AOD issues | 26 (61.9) | 10 (23.8) | 6 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Referrals | ||||||

| I was able to manage my patients without having to refer them to the GSMHS as a result of the advice I received | 29 (69.0) | 10 (23.8) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Overall satisfaction | ||||||

| My calls were answered timely | 40 (95.2) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| I am satisfied with the advice I received through the GPPPL | 39 (92.9) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| I am satisfied with the GPPPL | 39 (92.9) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

There was a strong level of agreement on the positive impact of the advice received on perceived increased clinical skills and confidence on individual patient management; however, the scores were somewhat lower for the statements relating to the impact on clinical skills and confidence overall. The level of agreement on the positive impact of the advice received on perceived knowledge was lower when compared with perceived skills and confidence scores, especially the statement on impact on perceived knowledge overall.

Only two survey respondents identified potential barriers to accessing the line. One cited lack of awareness about the line among some GPs, whereas the other cited having little requirement for this type of support.

Survey results also identified a positive impact on GPs’ ability to manage their patients without having to refer them to the GSMHS. This was consistent with interview data, with the majority of GPs reporting that accessing the GPPPL had resulted in fewer referrals to specialist services. GPs acknowledged that some referrals were still necessary, but even in those cases, having immediate access to expert advice allowed them to manage their patients more effectively in the interim.

GPs discussed referrals in the context of the barriers to health care access their patients faced, including lengthy waiting lists and travel distance, and the costs associated with private consultations. Thus, GPs identified cascading positive impacts on all stakeholders as a result of their increased ability to manage their patients in the primary care setting; the following quote encapsulates this shared perception:

Well, I mean it benefits everyone doesn’t it? So, it benefits the psychiatrists and the psychiatry registrars, because they’re not seeing patients that can be managed in the GP setting, it’s benefitting the GP, because you’re upskilling them to manage trickier patients, and it’s benefitting the patient, because they’re not having to go to Albany for a review, so everyone benefits. Who benefits the most, probably the taxpayer, because it’s saving them a truckload of money. (I11, GP Fellow)

Thematic analysis results

The interview transcripts yielded three main themes: the criticality of timeliness; the building blocks of confidence; and trust.

Most interview participants spoke enthusiastically about the GPPPL, with some describing their overall experience as ‘fantastic’, ‘extremely positive’, ‘brilliant’ and even ‘revolutionary’. This enthusiasm was also expressed in similar terms in the survey data. Together with the quality of the advice received, the most highly valued feature of the GPPPL was that of timeliness, with all participants commenting on its criticality in the context of their busy workloads. Timeliness was conceptualised around two constructs: immediateness and accessibility.

When asked to comment on the most beneficial aspects of the GPPPL, interview participants typically spoke about having immediate access to ‘consultant-level’ advice. This was contrast with ‘the old ways’, when GPs were either unable to get expert advice or had to wait for a delayed call back. Immediate access, that is, the call being answered and advice provided during the consultation, enhanced GPs ability to manage their patients, especially given the limitations of short consultations; this was highly valued by all GPPPL users interviewed:

You can get clinical information quickly, but also when you have the patient sitting right in front of you, you can deliver better patient-centred care if you can find the answer to things straight away and – rather than putting in referrals and then waiting for weeks and then having appointments that – there’s just lots of delays with the old ways that we had before. (I06, GP Fellow)

Similarly, another GP commented on the importance of getting advice ‘in real time’:

So the most beneficial thing is getting support and advice in real time such that you can make decisions with a patient sitting in a consult with you, sitting in the consult room with you at the same time. So, that’s extremely beneficial in managing mental health patients, especially high-risk patients, because it’s very anxiety-provoking, and it’s not exactly safe to let a patient go whilst you’re awaiting feedback or advice from a psychiatrist who might not be available until later on in the day. So, I feel like that’s probably the most beneficial thing. (I10, GP Registrar)

All GPs who had used the service agreed that accessing the GPPPL was quick and straightforward, with most calls answered straight away and no ‘administrative hurdles’. One GP explained:

You can just ring them anytime, and they – I’ve probably only rung up a few times, but every time, they’ve answered it pretty much straight away. And if they can’t talk, then they call you back really quickly. (I13, GP Fellow)

A single dedicated mobile number that can be easily stored in their own mobile phone was perceived as facilitating access to the service, compared with online logging systems. Overall, ease of access was highly valued among GPs and was perceived as one of the facilitators of access to the GPPPL, as this quote reflects:

I don’t think you need to fill out 10 forms and wait in queue and whatnot. I think it’s just a simple matter of phoning a number and speaking to someone. (I07, GP Fellow)

A strong consensus was observed about the positive impact of accessing the GPPPL on perceived increased confidence in managing their patients’ mental health problems. One GP Registrar explained:

I think my confidence has significantly increased through speaking with the consultants. I’ve found the advice that they give, their sort of education and the support has been actually really empowering. I didn’t expect that with the phone line. I kind of expected the phone line just to be a quick sort of one-stop shop for some advice, but to get reassurance from the consultant that you’re doing the right thing and your management plans are sound, I guess it makes me more confident in managing my mental health patients, for sure. (I10, GP Registrar)

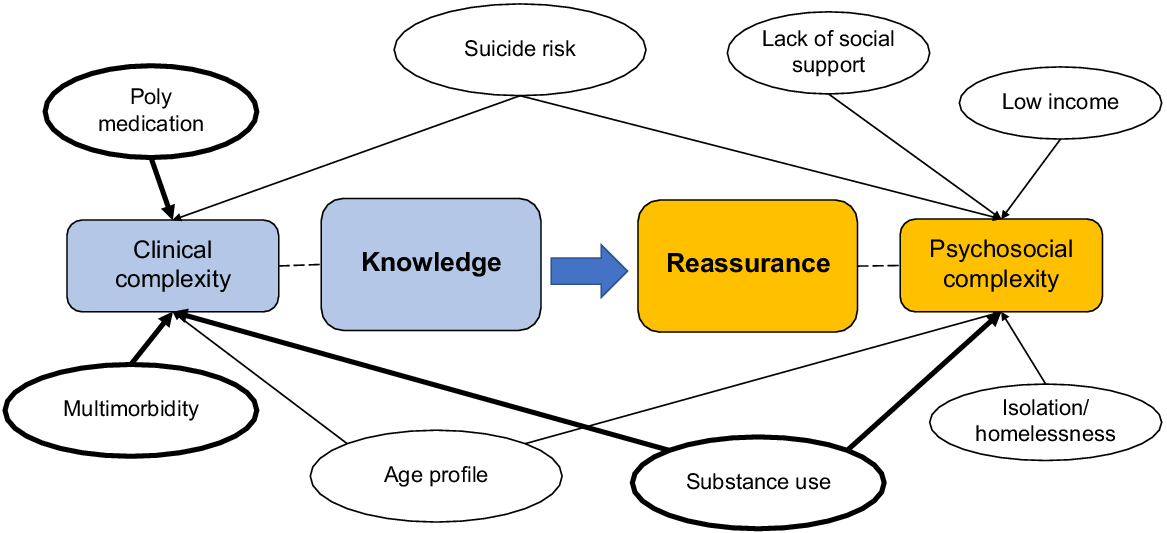

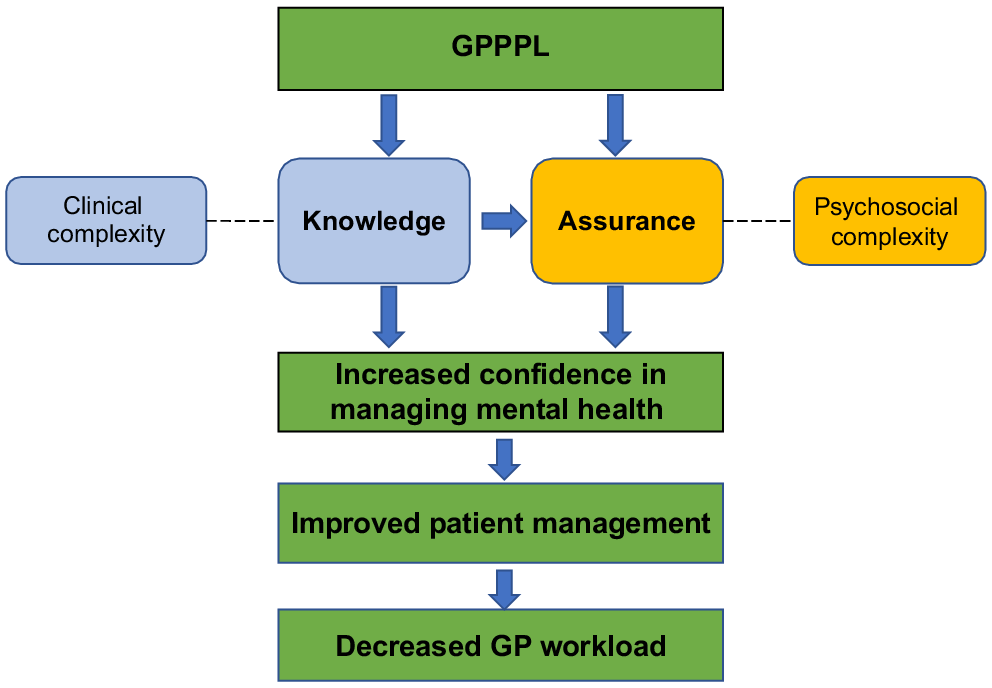

The quote above illustrates the mechanisms through which the GPPPL may help build confidence and, in turn, lead to improved patient management and reduce GP workload: strengthening knowledge and providing reassurance (see conceptualisation in Fig. 2).

Mechanisms through which increased confidence may operate and associated domains of patient complexity.

When asked to reflect on the impact of accessing the GPPPL on perceived levels of knowledge and skills, the level of agreement was somewhat lesser than that achieved around perceived impact on confidence (this is consistent with survey data). Only a few GP participants explicitly admitted to having knowledge gaps on mental health; however, increased knowledge and skills were broadly regarded as being intrinsically linked to increased confidence in managing mental health issues. Reflecting on the impact of the GPPPL, one GP explained the knock-on effect of increased knowledge and skills on referrals:

It’s had a good impact, because I know that if I’ve got that tricky patient I don’t need to send them for a tertiary – into a psych review, I can call up and get the information I need straightaway and then I can just continue to manage the patient, and so it avoids physically for my patients to having to travel to Albany for something, and then it makes me more confident, and next time I have something similar I’m like, ‘Okay, that’s the advice I got last time, let’s just do that this time’. (I11, GP Fellow)

The positive impact on knowledge and skills tended to be discussed in the context of the clinical complexity associated with the medical management of patients with multimorbidity, multiple psychiatric problems, polysubstance use or polyprescription use issues (see visualisation of the two domains of patient complexity in Fig. 3). GP Registrars tended to emphasise this knowledge-building aspect more readily compared with GP Fellows; they especially valued this educational aspect, as they did not always have a senior GP available within the practice. One GP Registrar explained:

I guess a good example is, I‘ve got a gentleman with bipolar who’s on lithium and he was getting more anxiety-type symptoms, and I just had a chat to someone on the GP psychiatry line and they recommended that I start [medication name] and it had yeah, really positive effects and so I’ve been able to then use that again in a similar patient, whereas before, because they had bipolar and it was complex and I wouldn’t have felt that confident mixing medication, crossing over medications with lithium, I might not have started that – I wouldn’t have started that myself and it would have been a referral I guess to mental health that could have been avoided. (I12, GP Registrar)

The GPPPL provided reassurance to GPs that they were handling ‘difficult decisions’ safely. Some GPs expressed feelings of worry, as they spoke about ‘anxiety-provoking’ patients and decisions that ‘keep them up at night’ or they are ‘in a bind’ about:

It’s just the help down the phone when you’ve got a situation that you feel uncomfortable with, or something needs to be done – instead of sending them up to ED, or putting in the referral, and that you don’t know when that’s going to be actioned, or going home and fretting about, “Have I done the right thing?” you’ve got an instant answer over the phone, or instant advice over the phone. It’s very reassuring to have that over the phone. (I01, GP Fellow).

Participants’ accounts suggested that most ‘difficult decisions’ were linked to patients’ psychosocial circumstances rather than clinical complexity per se. Thus, they tended to highlight the reassurance provided by the GPPPL about specific patient cohorts, including youth – especially youth at risk of suicide, patients with AOD and prescription medication use problems, and patients lacking social support. One GP spoke about an ‘influx’ of new patients with multiple medication and psychiatric issues that some colleagues were ‘terrified of taking on’. Another described the reason for one of their calls to the GPPPL:

… it was something about – some kind of complex social support situation where I wasn’t really sure what the correct ethical thing to do was in the context of the patient and the mental health problem, and sorting it out. (I06, GP Fellow)

Having a trusted sounding board when making difficult decisions was especially valued, given the isolation experienced in the rural setting:

… you sometimes do feel isolated, you may have colleagues in the same practice, but mostly you’re always by yourself, and you feel very responsible and very much on the front line, but it gives you the confidence that you can – that someone’s got your back that there is support and a safety net there. (I05, GP Fellow)

The reassurance of knowing the GPPPL is there, even if not accessed, was also noted:

There’s a confidence that comes from knowing that there’s someone there who can help you, even if you don’t necessarily take advantage of it. So, just knowing that there is someone who’s accessible and available and knowledgeable who can give advice if we need it. And I’ve seen my colleagues using the support as well, and I know what it was like before we had that. And I think that we feel more confident and we’re probably giving better care as well, because we’re having that much more support to do it properly. (I06, GP Fellow)

Participants’ accounts showed that trust in the GPPPL psychiatrists was a critical part of the effectiveness of the service, and that lack of trust may be a barrier to access. This was demonstrated by GPs’ opinions on the perceived level of expertise of the GPPPL psychiatrists and their reports of their ongoing professional relationships with them.

The GPPPL psychiatrists were widely regarded as being experts in their field. GPs valued the ability of GPPPL psychiatrists to provide ‘top-level’, appropriate advice on the spot with confidence and clarity. Reflecting on the impact on the GPPPL, one GP said:

I know that there’s essentially an expert down the phone that I can call at a moment’s notice to give me the appropriate advice. (I01, GP Fellow)

GPs sometimes spoke of their high regard for the expertise of GPPPL psychiatrists by contrasting their experience of accessing the GPPPL with that of accessing other helplines or specialist teams. A previous negative experience with other telephone services was seen as a potential barrier to accessing the GPPPL, as this GP explained:

I think that, unfortunately, a lot of GPs have the experience of contacting specialty teams in tertiary hospitals and speaking to a registrar, and it’s not always – the advice you get can be very variable. So, I think maybe that puts some people off, and people don’t realise that with the psychiatry line, it’s specific people who are answering, I suppose. (I08, GP Fellow)

The quote suggests a certain degree of scepticism that is consistent with the rest of this GP’s account which, in contrast with that of the rest of the sample of GPs who had accessed the GPPPL, demonstrated a more nuanced attitude towards the service, perhaps influenced by a reported preference for email over telephone consultations. During the interview, this GP expressed their trust in one particular psychiatrist, but was unsure about the area and level of expertise of the rest of the GPPPL team, adding that ‘you’re not 100% sure if they’re going to be the best person to give me advice’; later, he explained:

So, I think something that would potentially be helpful would be – I think we’ve been sent out before a list of people who answer the phone, but their little profile might be helpful. So, like, you’ll either get this person, who is a consultant psychiatrist and has experience with these subspecialty areas, or this person, who has this. And so you kind of know who you’re talking to. I think that would help. I think that would be useful.

Most GPs reported having an ongoing professional relationship with GPPPL psychiatrists prior to the commencement of the service. When asked about how they would access appropriate advice prior to the GPPPL, GPs typically reported asking their supervisor (in the case of GP Registrars) and their colleagues or reaching out to their professional networks through what one GP called ‘an informal mates system’. For those with established professional relationships with local psychiatrists, the GPPPL was seen as formalising something that was already occurring. One GP said:

It’s really nice to have an official way that you can do that, if that makes sense, because you’re not relying on somebody’s goodwill and you’re not relying on being friends with someone to have that kind of access to specialists. I think it’s a really good thing for people who are new to the region who don’t necessarily have those contacts yet. (I13, GP Fellow)

Building and strengthening contacts within the region was noted as an additional benefit of the GPPPL. Both GP Registrars and GP Fellows spoke about the educational aspect of the GPPPL and how it benefited more junior GPs. One GP with 10 years’ experience in the region commented:

I think that the other effect of these kinds of initiatives is that it improves trust between the GPs and the mental health unit, and improves relationships and knowing one another. (I06, GP Fellow).

Discussion

GPs were highly satisfied with the GPPPL, and they reported increased confidence and knowledge about mental health and AOD issues as a result of accessing the service. The GPPPL built GPs’ confidence through strengthening knowledge and providing reassurance, and timeliness and trust in the quality of the advice received were the main characteristics underpinning its effectiveness.

Our qualitative findings on timeliness are consistent with existing evidence (Sankaranarayanan et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2016), as are our survey and interview results on the impact of timely advice on decreased unnecessary referrals (Wilson et al. 2016). Given that most GPs in our sample raised concerns about access barriers to specialist mental health services in the region, it can be argued that enhancing the ability of GPs to manage their patients’ mental health issues and, thus, reducing the number of unnecessary referrals and simplifying the patient journey is especially salient in rural locales characterised by multifaceted accessibility issues. In this context, a service, such as the GPPPL, is congruent with the notion of ‘context-based accessibility’ (Coleman et al. 2022) and, we argue, more aligned with the place-based approaches and tailored-to-context service models proposed in the Orange Declaration on Rural and Remote Mental Health (Perkins et al. 2019; Coleman et al. 2022).

Trust in the GPPPL was underpinned by the perceived level of expertise of the psychiatrists and this was, in turn, positively influenced by existing ongoing professional relationships. Our results are consistent with evidence showing that interpersonal knowledge enhances communication and collaboration between GPs and mental health professionals (Fredheim et al. 2011), and support other Australian evidence pointing at the benefit of interacting with local psychiatrists with knowledge of the local context, including resource issues (Sankaranarayanan et al. 2010). Our data suggest that promoting mutual knowledge might be especially beneficial to more junior GPs; although our study was not designed to compare the experiences of GP Fellows and Registrars, this warrants further investigation.

Our survey and interview results show strong agreement on the positive impact of accessing the GPPPL on perceived confidence levels. Furthermore, our qualitative data illuminates two mechanisms through which accessing a service, such as the GPPPL, may result in increased confidence and, in turn, decreased GP workload: knowledge building and providing reassurance. These mechanisms were associated with two interconnected domains of patient ‘complexity’. Although the meaning attached to the notion of ‘complexity’ was not fully explored and warrants further investigation, our data suggest that GPs conceptualise ‘complexity’ as having two distinct domains: clinical and psychosocial.

The knowledge building attributed to accessing the GPPPL was largely linked to the discussion of clinical complexity. Although a certain reluctance to explicitly acknowledge knowledge gaps was observed among some GPs, the positive impact of accessing the GPPPL on knowledge and skills was more readily acknowledged in the context of discussing the clinical complexity associated with multimorbidity, multiple psychiatric problems, polysubstance use or polyprescription use issues. Our data on GPs’ perceived knowledge gaps on the management of AOD use are consistent with existing evidence (Wilson et al. 2022), and support the need to bolster GPs’ capacity through education and the development of stronger cross-sectional collaboration between GPs, mental health specialists and AOD services.

Accessing the GPPPL also resulted in increased confidence through providing reassurance around patients’ psychosocial complexity. Consistent with existing evidence (Braillard et al. 2018; McCallum and MacDonald 2021), our GPs experienced the emotional burden of dealing with patients’ complex psychosocial circumstances; furthermore, our results suggest that this burden is exacerbated when GPs deal with specific at-risk patient cohorts. In this context, accessing the GPPPL reassured GPs that they were making the ‘right’ decisions about their ‘anxiety-provoking’ patients.

Our data add to existing evidence that professional networks operate as a protecting factor against the greater isolation experienced by GPs in rural areas (Clough et al. 2020). We posit that the underlying mechanism through which the GPPPL may support GP workload is through distributing some of the burden of responsibility rural GPs experience. A service, such as the GPPPL, creates de facto multidisciplinary teams, effectively distributing agency and helping GPs negotiate the uncertainty and unpredictability of complex consultations (Innes et al. 2005).

The GPPPL was operated by local psychiatrists who are known to the GPs, and provide specialty care for the same population and, thus, have a stake in bolstering the capacity of GPs to manage mental health and AOD issues in the primary care setting. The value that rural GPs attach to accessing a locally-based specialist warrants further investigation, and has implications for the implementation of similar services in rural settings with similar workforce configuration and functioning.

Our findings add to the scarce literature on telephone-based specialist consultation services for GPs in Australia. We acknowledge three limitations. First, we interviewed a small sample of self-selected GPs, and GPs who had not used the service were underrepresented, which may have biased our results; however, we used survey results from a larger sample to triangulate our data. Second, our results are drawn from GPs practicing within one specific rural locale; however, our findings provide valuable insights that are applicable to other rural settings characterised by resource constraints. Third, the addition of AOD issues to the statements on perceived overall impact (absent on the statements on perceived impact on individual patient management) might have affected our survey results.

Our results suggest that a service, such as the GPPPL, operated by trusted, local psychiatrists with knowledge of the local mental health ecosystem of support, can reduce rural GP workload through building confidence and strengthening personal agency in mental health and AOD issues, helping GPs navigate the ethical and clinical labyrinth of managing patient complexity in rural settings.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

The WA Primary Health Alliance co-funded the trial of the GPPPL. This research did not receive any specific funding.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all survey and interview participants. We also acknowledge all the GPPPL psychiatrists.

References

Aknin LB, De Neve J-E, Dunn EW, Fancourt DE, Goldberg E, Helliwell JF, Jones SP, Karam E, Layard R, Lyubomirsky S, Rzepa A, Saxena S, Thornton EM, VanderWeele TJ, Whillans AV, Zaki J, Karadag O, Ben Amor Y (2022) Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science 17, 915-936.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) Health conditions prevalence. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/health-conditions-prevalence/2020-21 [Accessed 5 October 2022]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Mental health workforce. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/workforce [Accessed 16 June 2023]

Bradstock SE, Wilson AJ, Cullen MJ, Barwell KL (2005) Telephone-based psychiatry advice service for general practitioners. Medical Journal of Australia 183, 90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braillard O, Slama-Chaudhry A, Joly C, Perone N, Beran D (2018) The impact of chronic disease management on primary care doctors in Switzerland: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 19, 159.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clough BA, Ireland MJ, Leane S, March S (2020) Stressors and protective factors among regional and metropolitan Australian medical doctors: a mixed methods investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychology 76, 1362-1389.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Coleman M, Cuesta-Briand B, Collins N (2022) Rethinking accessibility in light of the Orange Declaration: applying a socio-ecological lens to rural mental health commissioning. Frontiers in Psychiatry 13, 930188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fredheim T, Danbolt LJ, Haavet OR, Kjønsberg K, Lien L (2011) Collaboration between general practitioners and mental health care professionals: a qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 5, 13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Green J, Willis K, Hughes E, Small R, Welch N, Gibbs L, Daly J (2007) Generating best evidence from qualitative research: the role of data analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 31, 545-550.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harrison C, Henderson J, Miller G, Britt H (2016) The prevalence of complex multimorbidity in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40, 239-244.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hoffman R, Mullan J, Bonney A (2023) “A cross-sectional study of burnout among Australian general practice registrars”. BMC Medical Education 23, 47.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Innes AD, Campion PD, Griffiths FE (2005) Complex consultations and the ‘edge of chaos’. British Journal of General Practice 55, 47-52.

| Google Scholar |

Koné Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, Calzavara A, Thavorn K, Petrosyan Y, Maxwell CJ, Bai YQ, Wodchis WP (2015) The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health 15, 415.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McCallum M, MacDonald S (2021) Exploring GP work in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation: a secondary analysis. BJGP Open 5, BJGPO.2021.0117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Patrick R, Snell T, Gunasiri H, Garad R, Meadows G, Enticott J (2023) Prevalence and determinants of mental health related to climate change in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57, 710-724.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Perkins D, Farmer J, Salvador-Carulla L, Dalton H, Luscombe G (2019) The Orange Declaration on rural and remote mental health. Australian Journal of Rural Health 27, 374-379.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

QSR International (2021) NVivo. Available at https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home [Accessed 8 March 2021]

Sankaranarayanan A, Allanson K, Arya DK (2010) What do general practitioners consider support? Findings from a local pilot initiative. Australian Journal of Primary Health 16, 87-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tian PGJ, Harris JR, Seikaly H, Chambers T, Alvarado S, Eurich D (2021) Characteristics and outcomes of physician-to-physician telephone consultation programs: environmental scan. JMIR Formative Research 5, e17672.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

WA Country Health Service (2021) Great Southern. Available at https://www.wacountry.health.wa.gov.au/Our-services/Great-Southern [Accessed 5 October 2022]

Western Australian General Practice Education and Training (2022) WA general practice education & training: 2020-21 annual report. Available at https://www.wagpet.com.au/media/11ofj5cb/wagpet-2020-21-annual-report.pdf [Accessed 21 June 2022]

Wieland L, Ayton J, Abernethy G (2021) Retention of general practitioners in remote areas of Canada and Australia: a meta-aggregation of qualitative research. Australian Journal of Rural Health 29, 656-669.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wilson M, Mazowita G, Ignaszewski A, Levin A, Barber C, Thompson D, Barr S, Lear S, Levy RD (2016) Family physician access to specialist advice by telephone: Reduction in unnecessary specialist consultations and emergency department visits. Canadian Family Physician 62, e668-e676.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wilson H, Schulz M, Rodgers C, Lintzeris N, Hall JJ, Harris-Roxas B (2022) What do general practitioners want from specialist alcohol and other drug services? A qualitative study of New South Wales metropolitan general practitioners. Drug and Alcohol Review 41, 1152-1160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |