Australian general practitioners’ views on qualities that make effective discharge communication: a scoping review

Melinda Gusmeroli A B , Stephen Perks A B * , Cassie Lanskey A B and Nicole Bates A

A B * , Cassie Lanskey A B and Nicole Bates A

A Townsville University Hospital, Townsville, Qld 4814, Australia.

B James Cook University, Townsville, Qld 4814, Australia.

Australian Journal of Primary Health 29(5) 405-415 https://doi.org/10.1071/PY22231

Submitted: 18 October 2022 Accepted: 8 May 2023 Published: 1 June 2023

Abstract

Transitions of patient care between hospital discharge and primary care are known to be an area of high-risk where communication is imperative for patient safety. Discharge summaries are known to often be incomplete, delayed and unhelpful for community healthcare providers. The aim of this review was to identify and map the literature which discusses Australian general practitioners’ (GPs) views on the qualities that make up effective discharge communication. Medline, Scopus and the Cochrane register of controlled drug trails and systematic reviews were searched for publications until October 2021 that discussed Australian GPs’ views on discharge communication from hospital to general practice. Of 1696 articles identified, 18 met inclusion and critical appraisal criteria. Five studies identified that GPs view timeliness of discharge summary receipt to be a problem. Communication of medication information in the discharge summary was discussed in six studies, with two reporting that GPs view reasons for medication changes to be essential. Five studies noted GPs would prefer to receive clinical discipline or diagnosis specific information. Four studies identified that GPs viewed the format and readability of discharge summaries to be problematic, with difficulties finding salient information. The findings of this scoping review indicate that GPs view timeliness, completeness, readability, medication related information and diagnosis/clinical discipline specific information to be qualities that make up effective discharge communication from hospital to the community. There are opportunities for further research in perspectives of effective discharge communication, and future studies on interventions to improve discharge communication, patient safety and policy in transfers of care.

Keywords: communication, general practitioners, health education, medical record linkage, medical records, medication systems, medication therapy management, patient discharge, pharmacy administration.

Introduction

Communication during transitions of care between hospital discharge and the community is a high-risk factor to patient safety (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2017a). The discharge communication from hospital to general practitioners (GPs) is important for patient handoff of clinical information, patient safety and to ensure continuity of patient care (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2017a). Inadequate communication during transitions of care, such as the absence of medication information or poor clarity of the discharge plan, is known to result in hospital re-admissions, patient related harm, mortality and associated costs (Van Walraven et al. 2002; Kripalani et al. 2007a, 2007b; Van Walraven et al. 2010; Tandjung et al. 2011; Okoniewska et al. 2015). Conversely, effective communication over transitions of care between discharge and the community increases consumer and carer satisfaction, and reduces medication adverse events, hospital re-admissions, complications post-discharge and mortality (Newnham et al. 2017). As such, specifically investigating what is deemed a necessity by GPs from this part of the patient’s journey is key to improving the continuity of patient care.

The discharge summary is a form of written communication that outlines diagnostic findings, hospital management, medication changes, information provided to the patient and follow up plans post hospital discharge. It is the most commonly used form of communication for handoff of clinical information from hospital discharge to the community (Kripalani et al. 2007b; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2017b). Unfortunately, poor discharge communication has been consistently documented in the literature in both Australia and overseas for decades, despite technology advances for generating discharge communication via computerisation (Kripalani et al. 2007b; Callen et al. 2008; Tandjung et al. 2011).

In 2017, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare released the second addition of the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (NSQHSS). Healthcare organisations in Australia are accredited to these standards every 3–4 years. They are a nationally consistent statement of the level of care consumers can expect from health service organisations (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2017a). Standard 6 specifically describes the ‘Communicating for Safety’ standard, and outlines transitions of care across organisations and discharge as an area of high-risk where communication is critical to patient safety. This standard focusses on a holistic handover of all medical information for the transfer of care of the patient. Standard 4 specifically describes the ‘Medication Safety’ standard, where continuity of medication management is a criterion assessed at accreditation, and provision of a medication list to the patient and receiving clinicians when handing over care on discharge is a requirement. The standards also discuss standardising and systemising processes to improve medication safety, and describes improving clinician–workforce communication and clinical handover as a recognised solution for reducing common causes of medication incidents (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2017a).

It is unclear what Australian GPs want and need in terms of quality, timeliness, method of communication and completeness of discharge summaries and communication. For these reasons, a scoping review was conducted to identify and map literature that discusses Australian GPs’ perceptions on the qualities that make up effective discharge communication. The objective of this scoping review is to identify gaps in knowledge to be able to inform future research and improve service delivery and patient safety in communication over transitions of care between hospital discharge and the community.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) procedure (Trocco et al. 2018) and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis: Scoping Reviews Protocol chapter (Aromataris and Munn 2020). A priori protocol was developed before undertaking the scoping review. The systematic scoping review protocol was registered with Open Science Framework on the 4th of October 2021.

The scoping review took a structured PCC (population/concept/context) approach. The target population was ‘patients discharging from hospital to primary care in Australia’, the concept was the ‘communication to General Practitioners at point of discharge’, and the context was the ‘General Practitioners’ perceptions of the ideal/best practice’ in this setting.

Eligibility criteria

Primary research papers were eligible for inclusion if they discussed patients discharging from hospital to primary care with discharge communication to GPs and GPs’ perceptions of best practice discharge communication in Australia. Limits were not set on dates of publication in the inclusion criteria. The reason for this is because what GPs perceived to be effective discharge communication years and even decades ago may still be relevant today.

Articles were excluded from review if they discussed discharge summaries to nursing homes, nursing discharge summaries, pharmacist only discharge medication records and summaries and allied health discharge summaries. Systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis, guidelines and standards were excluded from review.

Although there are some similarities between Australian and other healthcare systems, there are also vast differences in referral processes in care systems, models of subsidised GP consults and hospital funding which may affect a patient’s ability to link back into their primary healthcare network. For these reasons, only Australian studies were included for specificity.

Data sources – search strategy and information sources

A search was performed in Medline via OVID, Scopus and the Cochrane register. A combination of keywords and MeSH heading search terms were used, and full search strategies are listed in Supplementary Tables S1–S3. The reference lists of identified articles were also searched for additional sources of evidence.

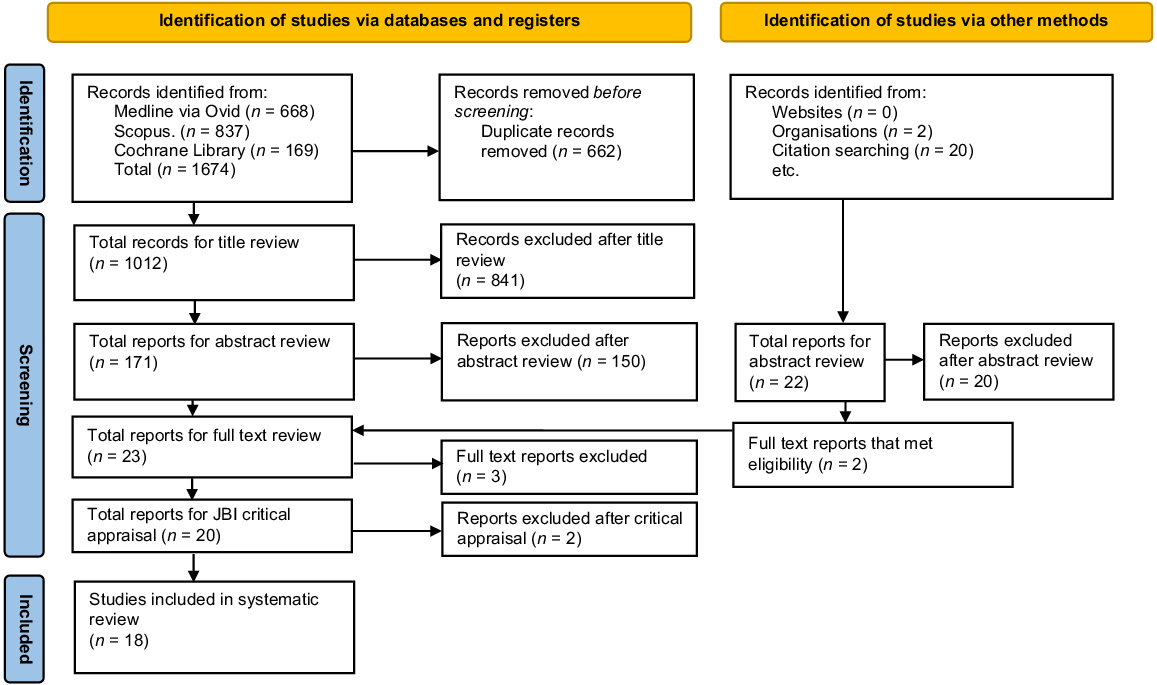

Endnote and Microsoft Excel software were used to manage results of the search. Out of 1674 results, 662 duplicates were removed by both automated and manual methods. Authors S.P. and M.G. screened the remaining 1012 titles, where 171 abstracts were then screened leaving 23 full text articles for review. After full text review, 20 articles met eligibility criteria and were retrieved for critical appraisal.

Critical appraisal of selected studies for inclusion

Three of the authors critically appraised the 20 full text articles independently using JBI critical appraisal tools. JBI critical appraisal tools were chosen to assess methodological quality for design bias, conduct and analysis of the selected studies in the systematic scoping review (Aromataris and Munn 2020). Of the 20 articles appraised, two did not meet critical appraisal due to being deemed poor quality studies scoring lower than 50% in the appraisal tools. All other studies were of high-quality scoring an average of 80% on applicable appraisal tools as seen in Table 1. Any inconsistent opinions on study selection were resolved by meeting and discussion.

| Author(s) (year of publication) | JBI critical appraisal score | |

|---|---|---|

| Alderton and Callen (2007) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Briggs et al. (2012) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Brodribb et al. (2016) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Castleden et al. (1992) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Chen et al. (2010) | 10 out of 13 | |

| Jiwa et al. (2014) | 10 out of 13 | |

| Karaksha et al. (2010) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Lane and Bragg (2007) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Mahfouz et al. (2017) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Middleton et al. (2004) | 8 out of 9 | |

| Stainkey et al. (2010) | 7 out of 9 | |

| Tran et al. (2020) | 8 out of 9 | |

| Williams et al. (2010) | 8 out of 9 | |

| Kable et al. (2015) | 7 out of 8 | |

| Kable et al. (2019) | 7 out of 8 | |

| Kilgour et al. (2019a) | 6 out of 8 | |

| Rowlands et al. (2012) | 7 out of 8 | |

| Kilgour et al. (2019b) | 8 out of 9 |

Results

Fig. 1 shows a PRISMA flow diagram, displaying the process of study selection in the systematic scoping review. A total of 18 studies were included for review that described GPs’ views on the qualities of effective discharge communication. Dates of publication range from 1992 to 2020. Of the 18 studies, 13 were quantitative, four were qualitive and one was a mixed-methods study design. Cross-sectional survey studies made up the majority of the quantitative studies. The study characteristics and outcomes identified in the included papers are displayed in Table 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies in the systematic scoping review and reasons for exclusion. From: Page et al. (2021). For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

| Author(s) (year of publication) | Aims/purpose objective | Methods (sample/participant details) | Clinical discipline (type of discharge communication practice) | Outcome measures and results relating to GPs views/perceptions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

| Alderton and Callen (2007) | Assess GPs satisfaction with quality information in electronic discharge summaries and timeliness of receipt | Cross-sectional survey (n = 54 GPs) | Geriatrics, general medicine, rehabilitation (Computer-generated discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 93% GPs agreed electronic discharge summary improved compared with manual discharge summary | ||

| Briggs et al. (2012) | Audit GP preferences of hospital discharge information after elective replacement surgery. | Clinical audit (n = 62 GPs) | Orthopaedic surgery (Discharge summaries) | GP preference – early post-operative actions required by GP, medication, post-operative complications, allergies considered essential | ||

| Brodribb et al. (2016) | Understand how GPs experience communication with hospital and other post-partum healthcare providers | Cross-sectional survey (n = 163 GPs) | Maternity (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 24.4% rarely/never received discharge summary timely. 43.8% thought it was very or 51.6% somewhat useful. | ||

| Castleden et al. (1992) | Assess GPs attitudes to computer-generated surgical discharge letters. | Cross-sectional survey (n = 86 GPs) | General surgery (Computer-generated discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 87.5% thought computer generated discharge summaries improved compared to standard discharge communication. 17% had not noticed discharge communication received timelier | ||

| Chen et al. (2010) | Examine delivery of computer-generated discharge summaries from hospital to general practice | Randomised controlled trial (n = 52 GP practices n = 168 discharges) | Geriatrics (Computer-generated discharge summaries) | GP preference – 82.7% preferred discharge communication to be received via fax | ||

| Jiwa et al. (2014) | Investigate the timing and length of hospital discharge letters and impact of ongoing patient problems identified by GPs | Randomised control trial (n = 59 GPs) | General surgery (Long/short discharge letters received early and late after discharge) | GP preference – GPs preferred longer discharge letter GP satisfaction – long or short discharge letter considered timely if received discharge letter before viewing patient-actor video. | ||

| Karaksha et al. (2010) | Investigate discharge summary quality and evaluate GP satisfaction with medication list in discharge summary | Cross-Sectional survey (n = 17 GPs) | Not specified (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 67% ‘most often’ received discharge summaries timely. 22% did not receive timely. 11 % never received at all. 67% ‘most often’ satisfied with quality of discharge summaries. 24% did not know about medication changes. 41% not often know reasons for medication changes. 22% never received discharge medication information. | ||

| Lane and Bragg (2007) | GPs opinions of communication and service received from ED of tertiary metropolitan hospital | Analytical cross-sectional survey (n = 147 GPs) | Emergency medicine (Discharge summaries) | GP preferences – 53% preferred current method of hand-delivery of discharge letters from patients, 36% preferred faxed discharge letters, 4% suggested email GP satisfaction – 58% rating standard of written communication as good or excellent. 45 GPs said never or rarely information missing from discharge summary | ||

| Mahfouz et al. (2017) | Develop a pilot discharge summary assessment tool that includes components that Australian GPs identify as most important for safe transfer of care. | A pilot cross-sectional survey (n = 118 GPs) | Not specified (Discharge summaries) | GP preferences – rated important or very important: Medications and reasons for changes, reason for admission, treatment in hospital, details of follow-up arrangements, list of diagnoses, results for diagnostic tests done in hospital. GP Satisfaction – very unsatisfied/unsatisfied with reasons for changes in medications (65.5%), pathology results (56.7%), format (46.9%), patient condition (41.7%). Satisfied or very satisfied with reason for admission (71.6%), with medications on discharge (66%). Themes identified – concerns about quality and content summaries, concerns timeliness of discharge summaries affecting continuity of care, format of discharge summaries too time-consuming, difficult to read, difficult to extract important information. | ||

| Middleton et al. (2004) | Determine patients’ knowledge about how many days expected to be hospitalised, perceptions of readiness to leave. Determine usefulness of discharge communications to GPs | Cross-sectional survey (n = 133 Patients n = 118 GPs) | Vascular surgery (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 67.3% discharge summaries received within 2 weeks of carotid endarterectomy rated very useful or useful, 93.5% surgeons’ post-operative letters received within 2 weeks of carotid endarterectomy rated very useful or useful | ||

| Stainkey et al. (2010) | Compare perceptions of hospital-based consultant educators and recipient GPs about discharge summary content and quality | Cross-sectional survey (n = 134 GPs n = 14 Consultants) | Not specified (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 60% very satisfied with principal diagnosis, 41.5% very satisfied with other active problems listed, 42.9% satisfied with clinical management listed chronologically, 43.4% very satisfied medication safely allowing for ongoing management, 40.7% very satisfied pathology results included, 37.5% satisfied GP recommendations being safe and adequate, 44.4% satisfied with information adequacy for ongoing management. Themes identified in comments – medication information missing, incomplete, inaccurate. Diagnosis vague, incomplete/missing, clinical information disagrees with principal diagnosis. Pathology not included, no indication for tests, abnormal results missing. Imaging results not included. Recommendations to GP missing or incomplete. Format difficult to read. Timeliness of receipt. | ||

| Tran et al. (2020) | Evaluate communication of post-operative opioid prescribing information provided by hospitals to GPs | Clinical audit and survey to GPs (n = 285 discharge summaries n = 57 GPs) | Opiate prescribing information in Surgery (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction −26.3% GPs satisfied with opioid information provided at discharge. Themes identified – opioid management plan not provided, discharge information on opioids inadequate. | ||

| Williams et al. (2010) | Examine healthcare service utilisation for patients discharge from hospital after ICU stay | Descriptive study (n = 112 Patients n = 59 GPs) | Intensive care (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – 9% unsatisfied/very unsatisfied information lacking regarding ICU admission in discharge summary. Themes identified – insufficient information in discharge summary about rehabilitation and ongoing needs | ||

| Qualitative studies | ||||||

| Kable et al. (2015) | Report acute, community and residential care health professionals’ perspectives on discharge process and transitional care arrangements for people with dementia and carers | Qualitative descriptive study (n = 8 GPs) | People with dementia (Discharge summaries, discharge medication communication) | GP satisfaction – GP concerns about inexperience of junior doctors writing discharge summaries, GPs commented on excessive prescribing for behavioural disturbances, GPs needing, but rarely received information on medication changes GP preference – GPs need entire medical history on discharge; it may be first time patient presenting; GP may not know patient is discharging. | ||

| Kable et al. (2019) | Understand health professionals’ perspectives on the discharge process and continuity of care from hospital to home for acute stroke survivors | Qualitative descriptive study (n = 4 GPs) | Stroke survivors (Discharge summaries, discharge medication communication) | GP satisfaction – GP concerns about discharge medication changes and risk. GP concerns about discharge summary received late, inadequate information about follow up, support required for patient, not considering functional, cognitive, social requirements. | ||

| Kilgour et al. (2019a) | Describe and analyse communication processes between hospital clinicians and general practitioners who provide postnatal gestational diabetes mellitus care. | Purposive sampling with convergent interviews (n = 16 GPs n = 13 hospital clinicians) | Maternity (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – discharge summaries contained too much detail, salient information hard to find, discharge summaries lacked information about ongoing management for women. Formatting, punctuation affecting readability of discharge summary. Important information not included. GP preferences – needing to know what happened in the admission and follow up plans for the GP to complete. Preference for doctor to doctor written discharge summaries. Preference for discharge summary to be written by an experienced doctor | ||

| Rowlands et al. (2012) | Investigate perceptions of the quality, format and timeliness of patient information that GPs receive from hospital-based lung cancer team | Qualitative exploration (n = 22 members of hospital team n = 8 GPs) | Medical oncology (Discharge summaries, discharge communication) | GP satisfaction – content and timeliness of communication with GPs is variable GP Preference – to receive direction in their responsibility in post-discharge follow up. Recommendation – a multidisciplinary discharge summary to support communication from hospital team to GP | ||

| Mixed methods | ||||||

| Kilgour et al. (2019b) | Communication perspectives, practices and preferences of women, hospital clinicians and GPs strategies that may promote completion of recommended postnatal gestational diabetes mellitus follow up | Exploratory mixed-methods (n = 16 GPs n = 13 new mothers n = 13 hospital clinicians n = 86 discharge summaries) | Maternity (Discharge summaries) | GP satisfaction – discharge summaries containing too many irrelevant details to the GP. Salient information omitted, difficult to find. GP Preference – to receive specific advice on gestational diabetes mellitus and for this information to be listed at the beginning of the discharge summary. GPs preferred less detailed information in intrapartum complication, long term management gestational diabetes mellitus and management of future pregnancies (compared with hospital clinicians). More detail preferred for complicated cases; less detail preferred for less complicated cases | ||

Of the 18 articles, three focused on computer-generated discharge summaries. These articles discussed that GPs prefer computer-generated discharge summaries compared to manual discharge summaries (Castleden et al. 1992; Alderton and Callen 2007). Most of the studies did not discuss whether discharge summaries were computer-generated or handwritten.

The remainder of the results section is broken into grouped result headings of timeliness, readability, completeness of the discharge summary relating to clinical discipline and diagnosis specific information and medication related information.

Timeliness of receipt of discharge summaries

Five articles discussed that GPs viewed timeliness of discharge summary receipt to be a problem (Castleden et al. 1992; Karaksha et al. 2010; Stainkey et al. 2010; Rowlands et al. 2012; Brodribb et al. 2016; Mahfouz et al. 2017). One article demonstrated that GPs appeared to be satisfied with timeliness (Middleton et al. 2004). None of the articles made reference to a specific timeframe, rather they reported on whether the GPs were happy with the timeliness of discharge summary delivery at the time of undertaking the study. Jiwa et al. (2014) had GPs undertake simulated post-discharge consultations with patient videos as surrogate for recently discharged patients. It found that the GPs considered the discharge summary to be timely if it was present by the time they viewed the patient simulation video rather than if it was received after the consultation video.

Length, formatting and readability of discharge summaries

Four studies identified that GPs had preferences regarding the overall format of the discharge summary communication. There was a preference noted from one study for longer more detailed discharge letters (Jiwa et al. 2014). Conversely, four other studies commented that it was difficult to find salient information from hard to read/interpret discharge summaries (Stainkey et al. 2010; Mahfouz et al. 2017; Kilgour et al. 2019a, 2019b), and that discharge summaries contain too much irrelevant detail (Kilgour et al. 2019a). One study concluded that 46.9% of GPs were very dissatisfied/dissatisfied with the format of discharge summaries, noting them to be too time-consuming, difficult to read and difficult to extract important information (Mahfouz et al. 2017).

Clinical disciplines and diagnosis related groups

It is noted in the literature that GPs have preferences for specific information in discharge summaries for different clinical disciplines and diagnosis related groups. Most studies focused on specific details that GPs felt were of particular importance for those patient groups.

Regarding general surgical patients, GPs perceived that discharge information on opioids was inadequate and that opioid management plans were not provided. Only 26.3% of GPs stated they were satisfied with opioid-related communication (Tran et al. 2020). Within this same study it was found that roughly one quarter of summaries had at least one discrepancy between opioids listed and opioids dispensed, and almost 90% of summaries did not contain an opioid management plan (Tran et al. 2020). Specifically, in elective total knee and hip replacement surgery, GPs rated early post-operative actions required by the GP, medications prescribed in hospital, allergies noted, summary of the surgical procedure and details on surgical/post-operative management, to be essential in discharge communication (Briggs et al. 2012).

For communication surrounding intensive care unit patients, only 9% of GPs were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied with lack of information pertaining to the intensive care unit admission in the discharge summary. This study identified that GPs perceived that there was insufficient information specifically about patient rehabilitation and ongoing patient care needs (Williams et al. 2010).

In people living with dementia, Kable et al. (2015) identified themes that commented on GPs needing to revise planned discharge medications for acute behavioural disturbances. GPs commented on excessive medication prescribing in this patient group, with medications often no longer required and with the potential for harm to these patients when returning to their home environment. Kable et al. (2019) also identified that information provided about stroke survivors was inadequate regarding follow up requirements, such as cognitive and support requirements (e.g. diet consistency, communication supports, mobility) and social issues (e.g. home environment, transport, driving).

For postnatal follow up of gestational diabetes mellitus patients, Kilgour et al (2019a) identified that GPs would like to receive specific advice on gestational diabetes mellitus care, and for this information to be listed at the beginning of the discharge summary. GPs preferred less detailed information about intrapartum complications, long term management of gestational diabetes and management of future pregnancies compared with hospital clinicians. GPs preferred more detail in discharge summaries for complicated cases and less detail for less complicated cases.

Communication of medication information at hospital discharge

Six studies discussed communication of medication related information at hospital discharge. Mahfouz et al. (2017) found that 65.5% of GPs were very unsatisfied or unsatisfied with medication changes in the discharge summary. Conversely, Stainkey et al. (2010) found that 43.4% of GPs were very satisfied with medications safely allowing for ongoing management. Themes identified by three of these studies were that medication information is often missing, incomplete or inaccurate in the discharge summary and that GPs need, but rarely receive, information about medication changes (Stainkey et al. 2010; Kable et al. 2015, 2019). Two other studies reported that GPs viewed the reasons for changes of medications as essential information (Briggs et al. 2012; Mahfouz et al. 2017).

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This scoping review identified 18 primary studies that investigated Australian GPs’ views on the qualities that make up effective discharge communication from hospital discharge to the community. This scoping review is the first to search and map the literature pertaining specifically to Australian GPs’ views of the qualities and preferences of discharge communication.

It is noted that themes found in this Australia specific review were similar to Clanet et al. (2015), which was an international systematic review published in 2015. Both systematic reviews found that timeliness, readability and diagnosis and treatment related information were important. The themes, and which publications discussed or referred to them, are listed in Table 3.

The findings identified that GPs prefer to receive clinical discipline and diagnosis specific information in discharge summaries (Williams et al. 2010; Briggs et al. 2012; Kable et al. 2015, 2019; Kilgour et al. 2019a; Tran et al. 2020). The wide range of detail that GPs prefer to receive for specific diagnoses, raises questions as to whether discharge summaries need to be better individualised and whether clinical coding could possibly be used to link diagnosis with diagnosis specific discharge summary templates to prompt clinicians to add pertinent information.

The range of data describing GPs’ views on timeliness of discharges summaries being received was conflicting. This ranged from GPs being satisfied with timeliness, to timeliness being listed as a problem with the handover process (Castleden et al. 1992; Middleton et al. 2004; Karaksha et al. 2010; Stainkey et al. 2010; Rowlands et al. 2012; Brodribb et al. 2016; Mahfouz et al. 2017). The findings from Jiwa et al. (2014) may explain this by way of noting that the preferred timeliness may not be specific to a fixed time frame, but rather if the discharge communication is received prior to the patient attending the GP for a post-discharge appointment. This raises questions about whether proactive planning and booking GP appointments may assist with the timeliness of discharge summary receipt, because there would be a better understanding about when the discharge summaries would need to be completed by. At the time of writing, in Australia there is no standard guidance or key performance indicator that dictates when a discharge summary or other forms of discharge communication should be completed or received by the recipient. Some individual facilities, or state-based health services, may provide guidance on this for clinicians, but it is not consistent. Implementation of standardised, evidence-based guidance of a time interval post-hospital discharge that the discharge summary is received within, could be a possible patient-safety quality improvement intervention.

It was clear in the data that medication related information in discharge summaries is of particular importance to GPs and is often incomplete or inaccurate. Time poor clinicians, and medication history not completed on admission, are some of the reasons for this. The evidence of poor communication of medication related information at hospital discharge alludes to the need for there to be more resources allocated to support improvements, for example, educational interventions, or greater pharmacist involvement in discharge communications. There is an example in the international literature of an expanded scope of prescribing pharmacists, with additional post-graduate training surrounding completing medical discharge summaries. This study showed that for discharge summaries written by these pharmacists, the discharge summary completion time, time to patient discharge and medication errors all decreased (Biggs and Biggs 2020). Australian hospital pharmacists are commonly involved with compiling medication lists as an education and communication tool for patients and community providers, however, they are not currently involved in writing discharge summaries as such.

Problems with discharge summary length, format and readability were identified in the literature (Stainkey et al. 2010; Jiwa et al. 2014; Mahfouz et al. 2017; Kilgour et al. 2019a, 2019b). In 2017, the Australian Commission on Quality in Healthcare released National Guidelines for On-Screen Presentation of Discharge Summaries, providing guidance on format, font and contents of electronic discharge summaries (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2017b). Thirteen of the included studies were published prior to 2017 when this guidance was released. None of the included studies that were published after 2017 compared discharge summary format or contents to the Australian guidance.

It was noted in the literature that most of the studies did not discuss whether the discharge summaries were or were not computer generated. This is significant to the scoping review question because the method of writing/generation of a discharge summary could affect its quality. It could be implied that more recent papers discuss computer-generated discharge summaries. Computer-generated or electronic discharge summaries started becoming commonplace in the last 10–15 years. The timelines for transition to these systems varies greatly across Australia.

Eight of the 18 included studies were published more than 10 years ago, and some aspects of those studies could now be considered outdated, particularly when taking into consideration recent technology advances pertaining to integrated electronic medical records in hospitals. None of the included studies investigated discharge communication since implementation of integrated electronic medical records. The timing for the implementation of use of these programs across Australia has varied greatly across the last 10–15 years.

This scoping review found that there is a paucity of Australian studies investigating other forms of discharge communication. With technology advances, there could be other ways in which discharge information could be communicated, for example, application-based methods or telehealth-based methods. There are some examples in the international literature of using application-based and video-based methods for providing discharge communication from hospital to patients or caregivers. These include application-based discharge communication to assist stroke patients after hospital discharge (Siegel et al. 2016), provision of audio–visual discharge instructions on pain and fever management to caregivers for acute otitis media in children (Belisle et al. 2019) and provision of audio–visual discharge instructions to general medical inpatients on discharge (Newnham et al. 2015). This scoping review did not identify any novel methods of communicating discharge information from hospitals to GPs in the Australian context.

It was also noted that most of the studies included for review were conducted at single healthcare institutions in metropolitan areas in Australia. Most of the studies did not specify whether they were tertiary hospital facilities or other smaller (primary or secondary) hospital facilities. There was a lack of representation of studies conducted that included regional, rural and remote areas, which would be an area of interest for future research. A lack of large sample sizes within the studies identified was also observed (samples sizes ranged from 4 to 163 GPs). Studies with larger sample sizes would be able to provide a more robust evidence base to be able to guide recommendations and practice change relating to discharge communication. Future studies with a broader capture, for example, in multi-site studies of larger sample sizes, inclusive of rural and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander patient demographics, would ensure that results are better representative of the wider Australian population. Including these patient demographics in future studies would provide a better understanding of what GPs need regarding discharge communication for these specific patient groups.

Conclusions

The aim of this scoping review was to investigate what is desired from Australian GPs in discharge communication, as a key to improving continuity of care in this part of the patient journey. To the authors’ knowledge, this paper is the first to search and map the literature specifically pertaining to GPs in Australia. The findings of this scoping review indicate that timeliness, completeness, readability, medication related information and diagnosis/clinical discipline specific information are qualities that comprise effective discharge communication from hospital discharge to the community. There is very little content regarding GPs’ views specifically about communication post the implementation of electronic prescribing platforms, which should be further pursued. The importance of the clear, concise collation and handover of information becomes even more important as we move further into the electronic age, where we have even more information at our fingertips. It is imperative that we get this right for the continuum of care for our patients.

Implications for research and practice

In mapping the literature pertaining to Australian GPs’ views on the qualities that make up effective discharge communication, this scoping review has identified gaps in the current evidence base.

There are opportunities for future research and practice change with the aim of improving patient outcomes, patient safety and subsequent economic benefits to health services in the following areas:

Addressing deficits in medication information in discharge communication.

Interventions to improve timeliness of GPs receiving discharge communication.

Digital technology-based interventions to improve discharge communication.

Other novel forms of communication.

Educational interventions for junior medical officers; to be able to support them to better communicate discharge information.

Discharge communication requirements for specific clinical disciplines, diagnosis related groups or patient demographics.

Larger sample-sized, multi-site cross-sectional studies to affirm what smaller studies, across single-site institutions, have found.

Assessing the quality of discharge communication since the introduction of integrated electronic medical records.

References

Alderton M, Callen JL (2007) Are general practitioners satisfied with electronic discharge summaries? Health Information Management Journal 36, 7-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Aromataris E, Munn ZE (2020) JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Available at https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Accessed 4 October 2021]

Belisle S, Dobrin A, Elsie S, Ali S, Brahmbhatt S, Kumar K, Jasani H, Miller M, Ferlisi F, Poonai N (2019) Video discharge instructions for acute otitis media in children: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Academic Emergency Medicine 26, 1326-1335.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Biggs MJ, Biggs TC (2020) Independent prescribing pharmacists supporting the early discharge of patients through completion of medical discharge summaries. Journal of Pharmacy Practice 33, 173-175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Briggs AM, Lee N, Sim M, Leys TJ, Yates PJ (2012) Hospital discharge information after elective total hip or knee joint replacement surgery: a clinical audit of preferences among general practitioners. Australasian Medical Journal 5, 544-550.

| Google Scholar |

Brodribb WE, Mitchell BL, Van Driel ML (2016) Continuity of care in the post partum period: general practitioner experiences with communication. Australian Health Review 40, 484-489.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Callen JL, Alderton M, McIntosh J (2008) Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries. International Journal of Medical Informatics 77, 613-620.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Castleden WM, Stacey MC, Norman PE, Brooks JG, Spence RD, Bolton BR, Van Merwyck AJ, Faulkner KW, Minchin DE, Lawrence-Brown MMD (1992) General practitioners’ attitudes to computer-generated surgical discharge letters. The Medical Journal of Australia 157, 380-382.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chen Y, Brennan N, Magrabi F (2010) Is email an effective method for hospital discharge communication? A randomized controlled trial to examine delivery of computer-generated discharge summaries by email, fax, post and patient hand delivery. International Journal of Medical Informatics 79(3), 167-172.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clanet R, Bansard M, Humbert X, Marie V, Raginel T (2015) Systematic review of hospital discharge summaries and general practitioners’ wishes. Sante Publique 27(5), 701-11.

| Google Scholar |

Jiwa M, Meng X, O’Shea C, Magin P, Dadich A, Pillai V (2014) A randomised trial deploying a simulation to investigate the impact of hospital discharge letters on patient care in general practice. BMJ Open 4, e005475.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kable A, Chenoweth L, Pond D, Hullick C (2015) Health professional perspectives on systems failures in transitional care for patients with dementia and their carers: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Services Research 15, 567.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kable A, Baker A, Pond D, Southgate E, Turner A, Levi C (2019) Health professionals’ perspectives on the discharge process and continuity of care for stroke survivors discharged home in regional Australia: a qualitative, descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 21, 253-261.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Karaksha AA, Hattingh HL, Hall T (2010) Quality of discharge summaries sent by a regional hospital to general practitioners. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 40, 208-210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kilgour C, Bogossian F, Callaway L, Gallois C (2019a) Experiences of women, hospital clinicians and general practitioners with gestational diabetes mellitus postnatal follow-up: a mixed methods approach. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 148, 32-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kilgour C, Bogossian FE, Callaway L, Gallois C (2019b) Postnatal gestational diabetes mellitus follow-up: perspectives of Australian hospital clinicians and general practitioners. Women and Birth 32, e24-e33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA (2007a) Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2, 314-323.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW (2007b) Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 297, 831-841.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lane N, Bragg MJ (2007) From emergency department to general practitioner: Evaluating emergency department communication and service to general practitioners. Emergency Medicine Australasia 19(4), 346-352.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mahfouz C, Bonney A, Mullan J, Rich W (2017) An Australian discharge summary quality assessment tool: a pilot study. Australian Family Physician 46, 57-63.

| Google Scholar |

Middleton S, Appleberg M, Girgis S, Ward JE (2004) Effective discharge policy: are we getting there? Australian Health Review 28, 255-259.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Newnham HH, Gibbs HH, Ritchie ES, Hitchcock KI, Nagalingam V, Hoiles A, Wallace E, Georgeson E, Holton S (2015) A feasibility study of the provision of a personalized interdisciplinary audiovisual summary to facilitate care transfer care at hospital discharge: Care Transfer Video (CareTV). International Journal for Quality in Health Care 27, 105-109.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Newnham H, Barker A, Ritchie E, Hitchcock K, Gibbs H, Holton S (2017) Discharge communication practices and healthcare provider and patient preferences, satisfaction and comprehension: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 29, 752-768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Okoniewska B, Santana MJ, Groshaus H, Stajkovic S, Cowles J, Chakrovorty D, Aghali W (2015) Barriers to discharge in an acute care medical teaching unit: a qualitative analysis of health providers’ perceptions. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 8, 83-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rowlands S, Callen J, Westbrook J (2012) Are general practitioners getting the information they need from hospitals to manage their lung cancer patients? A qualitative exploration. Health Information Management Journal 41, 4-13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Siegel J, Edwards E, Mooney L, Smith C, Peel JB, Dole A, Maler P, Freeman WD (2016) A feasibility pilot using a mobile personal health assistant (PHA) app to assist stroke patient and caregiver communication after hospital discharge. mHealth 2, 31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stainkey L, Pain T, McNichol M, Hack J, Roberts L (2010) Matched comparison of GP and consultant rating of electronic discharge summaries. Health Information Management Journal 39, 7-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tandjung R, Rosemann T, Badertscher N (2011) Gaps in continuity of care at the interface between primary care and specialized care: general practitioners’ experiences and expectations. International Journal of General Medicine 4, 773-778.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tran T, Taylor SE, George J, Pisasale D, Batrouney A, Ngo J, Stanley B, Elliott RA (2020) Evaluation of communication to general practitioners when opioid-naïve post-surgical patients are discharged from hospital on opioids. ANZ Journal of Surgery 90, 1019-1024.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Trocco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, et al. (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169, 467-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A (2002) Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17, 186-192.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Etchells E, Bell CM, Stiell IG, Zarnke K, Forster AJ (2010) The independent association of provider and information continuity on outcomes after hospital discharge: implications for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine 5, 398-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Williams TA, Leslie GD, Brearley L, Dobb GJ (2010) Healthcare utilisation among patients discharged from hospital after intensive care. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 38, 732-739.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |