Identification and nutritional management of malnutrition and frailty in the community: the process used to develop an Australian and New Zealand guide

Megan Rattray A B * and Shelley Roberts

A B * and Shelley Roberts  A C

A C

A

B

C

Abstract

Malnutrition and frailty affect up to one-third of community-dwelling older adults in Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), burdening individuals, health systems and the economy. As these conditions are often under-recognised and untreated in the community, there is an urgent need for healthcare professionals (HCPs) from all disciplines to be able to identify and manage malnutrition and frailty in this setting. This paper describes the systematic and iterative process by which a practical guide for identifying and managing malnutrition and frailty in the community, tailored to the ANZ context, was developed. The development of the guide was underpinned by the Knowledge-to-Action Framework and included the following research activities: (1) a comprehensive literature review; (2) a survey of ANZ dietitians’ current practices and perceptions around malnutrition and frailty; (3) interviews with ANZ dietitians; and (4) a multidisciplinary expert panel. This resulted in the development of a guide tailored to the ANZ context that provides recommendations around how to identify and manage malnutrition and frailty in the community. It is now freely available online and can be used by all HCPs across several settings. The approach used to develop this guide might be applicable to other conditions or settings, and our description of the process might be informative to others who are developing such tools to guide practice in their healthcare environment.

Keywords: community, dietitian, frailty, guidance, healthcare professionals, identify, malnutrition, manage.

Introduction and context

Malnutrition and frailty are common in Australian and New Zealand (ANZ) communities, and although distinct from each other, share overlapping causes and consequences (Laur et al. 2017). For example, both are associated with a range of negative outcomes for individuals and institutions, such as increased risk of falls and fractures (Kojima 2015), mortality (Thompson et al. 2021), functional decline (Kojima 2015, 2018; Griffin et al. 2020), hospitalisation (Kojima 2019) and increased healthcare costs (Abizanda et al. 2016; Sulo et al. 2020). Nutrition intake is a major modifiable risk factor in the development and progression of both conditions (Roberts et al. 2021) and consequently, treatment usually involves strategies to increase dietary intake. Despite this, the prevalence of malnutrition (1–17% of ANZ adults) and frailty (2–29% of ANZ adults) remains high in the community (Roberts et al. 2021). Further, up to 60% of community-dwelling older adults are estimated to be at risk of developing either one of these conditions (Roberts et al. 2021). These statistics are alarming given ANZ communities have ageing populations, with the number of people aged ≥80 years expected to increase by >200% by 2050 (Kowal et al. 2014). As such, there is an urgent need for healthcare professionals (HCPs) to be able to understand, recognise and act on suspected malnutrition and frailty among community-dwelling adults.

HCPs from all disciplines who interact with community members, including medical, nursing and allied health practitioners, have a responsibility for identifying and managing malnutrition and frailty. However, these conditions are often unidentified and untreated in the community (Dwyer et al. 2020). Poor communication and collaboration between HCPs and across healthcare services, insufficient knowledge/attention to nutritional needs/problems by HCPs, and limited access to services have been described as barriers to delivering nutrition care in the community (Holst and Rasmussen 2013; Lim et al. 2018; Hestevik et al. 2019). Compounding these issues is a lack of specific guidance for HCPs to identify and treat these conditions in the community.

To help address this gap, our team has developed the first ANZ nutrition guide, for use by all HCPs, on identifying and managing malnutrition and frailty among clients in the community and those transitioning home from hospital. A guide in the context of chronic condition management refers to a resource that provides practical advice, suggestions, or step-by-step instructions for specific scenarios or procedures (Kovacs Burns et al. 2014). Although the development of a guide might be considered less rigorous than that of a guideline, guides still hold valuable use in practice. For example, guides might offer flexibility by presenting a range of management options, considering various clinical scenarios, and discussing the nuances of decision-making; emphasise the importance of individualised client care, integrating evidence-based recommendations with the clinician’s experience, intuition, and client preferences; and facilitate interdisciplinary communication and collaboration by presenting a holistic view of the disease and its management. The aim of this paper is to describe the process by which this practical, accessible, and flexible guide was developed.

Develepoment of the guide

Development of the guide was underpinned by the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) Framework, given this framework provides a comprehensive approach to bridging the gap between evidence (research knowledge) and its application in practice (Graham et al. 2006). Specifically, the development process addressed the first three steps of the ‘Action Cycle’, through the following research activities: (1) identifying the problem (reviewing the literature); (2) adapting knowledge to the local context (surveying and interviewing ANZ dietitians, gaining consensus from a multidisciplinary expert panel); and (3) assessing barriers to knowledge use (surveying and interviewing ANZ dietitians). Each research activity served a distinct purpose and the findings generated were used to inform the guide’s content (Table 1).

| Research activity | Purpose | Findings | Integration of findings into guide | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Review | To understand malnutrition and frailty and identify the best available research evidence to structure and inform the guide. |

| ||

Surveys | To explore dietitians’ current practices around malnutrition and frailty to ensure guide content is tailored and relevant. |

|

| |

Interviews | To understand stakeholders A perspectives on identifying and treating malnutrition and frailty; and their preferences/needs for guide content. |

|

| |

Expert panel | To provide expert and contextual feedback on the content and layout of the guide. |

|

ANZ, Australia and New Zealand; HCP, healthcare professional; NCP, nutrition care process.

Reviewing the literature

A narrative review was undertaken (January–June 2021) to synthesise the available evidence on tools, interventions and evaluation strategies currently used to identify and manage malnutrition and frailty among community-dwelling adults. The review summarised original evidence reported by peer-reviewed ANZ studies published from 2010; however, published reviews synthesising international literature were also captured to improve the robustness and generalisability of our conclusions. This was an essential first step, providing evidence of the need for such a guide and an overall framework to develop the guide around. An overview of review findings is presented in Table 1 and in-depth results are published elsewhere (Roberts et al. 2021).

Surveying ANZ dietitians

Throughout March to May 2021, a cross-sectional survey was undertaken to explore practising ANZ dietitians’ (n = 186) current practices and perceived barriers/enablers to delivering quality nutrition care. This involved a 34-item survey administered through the web-based platform, LimeSurveyTM (Hamburg, Germany). Questions were on participant demographics; assessing and managing malnutrition and frailty; and discharge planning, referrals and follow-up for clients who are malnourished, frail or at risk. Responses were in various formats, including dichotomous, multiple choice, Likert scale or open-ended responses. Data were analysed descriptively. This step confirmed that practices for identifying malnutrition and frailty varied widely in the community, and although dietitians self-reported that they practiced person-centred nutrition care with malnourished/frail clients, they encountered many professional and resource-related barriers that must be considered when delivering evidence-based care. An overview of survey findings is presented in Table 1 and in-depth results are published elsewhere (Roberts et al. 2023).

Interviewing ANZ dietitians

Next, (April–June 2021) semi-structured phone interviews were conducted with a sub-sample of dietitians (n = 18) who participated in the survey, to understand their attitudes around the guide. A short scenario whereby the premise behind the guide and an outline of its content were presented to each interviewee to obtain their insight and feedback. This step was critical, as understanding one’s audience is necessary to customise guide content and the method of dissemination to better reach the intended users (Graham et al. 2006). Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using inductive content analysis to identify emerging categories (Elo and Kyngäs 2008). An overview of the categories identified from the scenario is presented in Table 1 and an in-depth analysis is presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Of note, we did intend to interview a sub-sample of consumers and non-dietetic HCPs (nurses, pharmacists and general practitioners); however, we were unable to recruit willing participants, despite advertising locally and on state-wide platforms, and offering monetary incentives (to consumers). For example, email advertisements were distributed by organisations across Australia to recruit consumers and non-dietetic HCPs, including Health Consumers NSW, Safer Care Victoria, Health Consumers Tasmania, Health Consumers Alliance of South Australia, Health Consumers’ Council WA, Health Care Consumers’ Association ACT, Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy and Australasian Association for Academic Primary Care. Second, several local general practices and health services in the community were directly emailed the study flyer to disseminate within their network. Finally, the nutrition clinic at Griffith University, who were likely to provide care to our intended sample population, agreed to disseminate the study flyer/advertisement to consumers.

Gaining consensus from a multidisciplinary expert panel

Finally, (June 2021–February 2022) 14 experts from various multidisciplinary fields (dietitians, geriatricians, client/consumer, exercise scientist, nurse, pharmacist) across ANZ were invited to contribute to the guide’s topics and content. Given existing empirical evidence suggests that panel composition has an impact on the content of the recommendations that are made (Fretheim et al. 2006), careful consideration was made to ensure the panel included important stakeholders such as consumers and HCPs that worked within the field and had experience with malnutrition and frailty. Input was sought from these experts to ensure the guide was of high quality and tailored to the needs of HCPs practicing across ANZ. To achieve this, a draft of the guide was circulated in a sequential manner, allowing each expert to build on the feedback of the other members. This occurred across two feedback cycles. Experts who had greater field experience were generally consulted early in each cycle given their practical insights. An explanation of how this research activity shaped the guide is presented in Table 1.

The guide

The guide was launched publicly in March 2022 and is freely available via the following link: https://nutricia.com.au/adult/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2022/02/ANZ_Community_Malnutrition_and_Frailty_Guidelines_March_2022_FINAL.pdf.

It includes guidance on multidisciplinary team roles and responsibilities in the identification and nutritional management of malnutrition and frailty, and information on: (1) the definitions, prevalence, causes and consequences of malnutrition and frailty; (2) how to identify at-risk clients using validated screening tools; (3) selecting and implementing nutrition interventions to manage these conditions; (4) transitions of care (from hospital to home); and (5) the types of community services and client resources available for these conditions. Although the guide has a community focus, it could also be used by HCPs working in other settings such as residential aged care or hospitals.

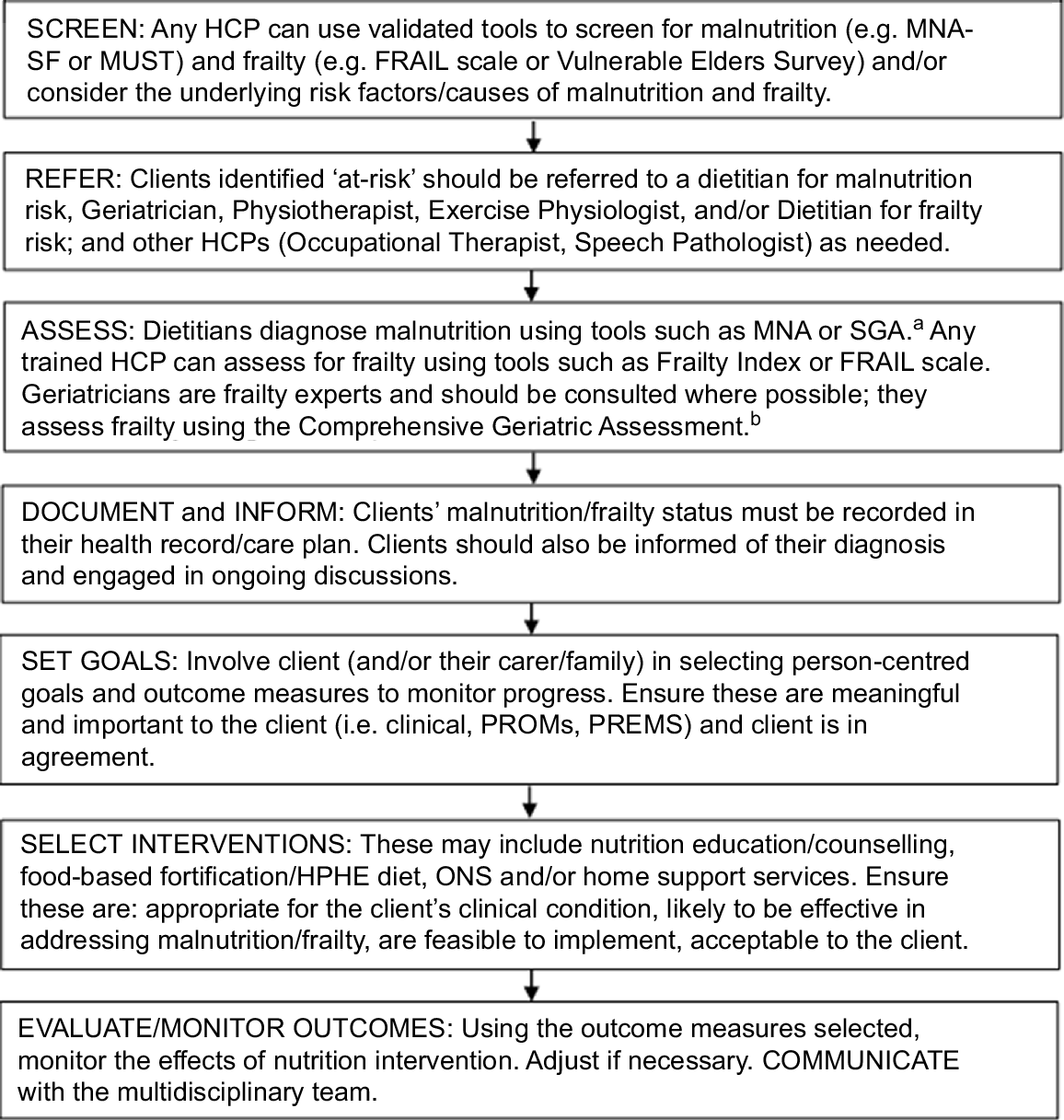

Fig. 1 outlines the steps recommended by the guide to identify and manage malnutrition and frailty in the community.

Research activities to identify and manage malnutrition and/or frailty. FRAIL, fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, and loss of weight; HCP, healthcare professional; HPHE, high protein, high energy; MNA, mini nutritional assessment; MNA-SF, mini nutritional assessment short form; MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; ONS, oral nutrition supplements; PREMs, patient- reported experience measures; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; SGA, subjective global assessment. aLow quality of evidence for the tool’s concurrent validity in community settings; more research is needed. bShould only be conducted by a geriatrician.

What can be learnt

Malnutrition and frailty affect a significant proportion of community-dwelling adults (Roberts et al. 2021). Given the consequences associated with these conditions, it is important for HCPs to be proficient in recognising and treating malnutrition and frailty in community settings. This practical guide should be used by HCPs to provide consistent and high-quality care for these conditions, using tools and approaches appropriate for each step.

Using the KTA Framework to underpin the research activities used to inform the development of this guide was instrumental. The first research activity involved a literature review that rigorously identified and synthesised relevant evidence to underpin the guide. Many organisations in Australia undertake systematic reviews to inform the development of evidence-based guides, guidelines or standards (McDonald et al. 2019), given this process is critical for translating the results of research into practice to ensure the best possible outcomes for clients (Rapport et al. 2018). The remaining research activities (surveys, interviews, and expert opinion) involved acquiring locally sourced data to tailor and contextualise the guide. Giving practicing dietitians an opportunity to provide specific feedback on the guide’s content was particularly beneficial. These discussions also shaped many practical aspects of the guide, including how it should be disseminated (i.e. by public domain URL vs publication in a journal; and adopting an active dissemination strategy by presenting the guide at webinars and conferences). Similarly, the expert panel addressed many practical considerations and helped tailor content. Previous work has found that publication and dissemination arrangements are a key aspect to consider during resource development and are influenced by the context of intended use (McDonald et al. 2019). When developing community-based guides, researchers and clinicians should equally consider the best available scientific evidence, as well as practical factors (tailoring, readability, dissemination), as this can increase the acceptability and perceived legitimacy to stakeholders (Rapport et al. 2018).

Involving stakeholders from all relevant groups, including community representatives (consumers) in the development of health guidance is ideal and considered best practice (Helbig et al. 2015). Our intention was to interview all relevant stakeholders to gather their insights for the guide’s development. However, despite our efforts to recruit through national organisations and local networks, engaging non-dietetic stakeholders, including consumers, general practitioners, nurses and allied health practitioners, proved particularly challenging. Consequently, we were only able to recruit dietitians, meaning the preliminary development of the guide was heavily guided by the perspectives of a single profession. This might be partly attributed to the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which placed additional strain on healthcare settings and practitioners, affecting their ability to spend time contributing to research (Pedrosa et al. 2020). Further, given the interviews took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, only one communication channel (email) was utilised to reach and recruit participants. Alternatively, it could reflect how under-recognised malnutrition and frailty are in the community by consumers and non-dietetic health practitioners, highlighting the need for this guide. Despite these challenges, the final version of the guide was shaped by an expert panel comprising healthcare professionals from various multidisciplinary fields, as well as a health consumer. This panel provided contextual feedback on the content and layout of the guide in multiple iterations, ensuring the inclusion of diverse and relevant viewpoints from all relevant key stakeholders. To improve recruitment of non-dietetic healthcare professionals and consumers in future endeavours involving nutrition-based resource development, we recommend the following: (1) collaborate with professional associations and utilise social media platforms to reach a wider audience; (2) engage local community organisations and establish partnerships with primary care providers to disseminate study information; (3) enhance study materials and incentives to effectively communicate the benefits of participation; and (4) utilise multiple communication channels, including email, phone calls, and in-person visits, to maximise outreach efforts.

Conclusion

This tool provides practical guidance for HCPs to identify and manage malnutrition and frailty in the community. Informed by current evidence and developed by a multidisciplinary panel of experts, it has also been tailored to the ANZ context based on feedback from HCPs experienced in managing clients who are malnourished and frail in the community. This comprehensive and iterative approach might inform others planning to develop guidance for the management of health conditions in the community or other settings.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by an unrestricted educational grant provided by Danone Nutricia. The funders were not involved in the designing or executing of the research activities or the development of the guide; however, they did approve the final version of the guide during the formatting and design process, which they led.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (revised 2013) and approved by the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 2021/048).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study and the expert panel who provided feedback on the guide during development. The expert panel members included: Tory Crowder, Prof Carol Wham, Chadia Bastin, Andrea Elliot, A/Prof David Scott, Prof Ruth Hubbard, Dr Natasha Reid, Steve Tobiano, Prof Andrea Marshall, Dr Janet Sluggett, Vanessa Schuldt, Julie Dundon, Prof Lauren Ball, and Dr Peter Collins. The authors also acknowledge Dietitians Australia and Dietitians New Zealand for reviewing and endorsing the guide.

References

Abizanda P, Sinclair A, Barcons N, Lizán L, Rodríguez-Mañas L (2016) Costs of malnutrition in institutionalized and community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17, 17-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dwyer JT, Gahche JJ, Weiler M, Arensberg MB (2020) Screening community-living older adults for protein energy malnutrition and frailty: update and next steps. Journal of Community Health 45, 640-660.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62, 107-115.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fretheim A, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD (2006) Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 3. Group composition and consultation process. Health Research Policy and Systems 4, 15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N (2006) Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26, 13-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Griffin A, O’Neill A, O’Connor M, Ryan D, Tierney A, Galvin R (2020) The prevalence of malnutrition and impact on patient outcomes among older adults presenting at an Irish emergency department: a secondary analysis of the OPTI-MEND trial. BMC Geriatrics 20, 455.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Helbig N, Dawes S, Dzhusupova Z, Klievink B, Mkude CG (2015) Stakeholder engagement in policy development: observations and lessons from international experience. In ‘Policy practice and digital science: integrating complex systems, social simulation and public administration in policy research’. (Eds M Janssen, MA Wimmer, A Deljoo) pp. 177–204. (Springer International Publishing: Switzerland)

Hestevik CH, Molin M, Debesay J, Bergland A, Bye A (2019) Healthcare professionals’ experiences of providing individualized nutritional care for older people in hospital and home care: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics 19, 317.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Holst M, Rasmussen HH (2013) Nutrition therapy in the transition between hospital and home: an investigation of barriers. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2013, 463751.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kojima G (2015) Frailty as a predictor of future falls among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 16, 1027-1033.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kojima G (2018) Quick and simple FRAIL scale predicts incident Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental ADL (IADL) disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 19, 1063-1068.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kojima G (2019) Increased healthcare costs associated with frailty among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 84, 103898.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kovacs Burns K, Bellows M, Eigenseher C, Gallivan J (2014) ‘Practical’ resources to support patient and family engagement in healthcare decisions: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 14, 175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kowal P, Towers A, Byles J (2014) Ageing across the Tasman Sea: the demographics and health of older adults in Australia and New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 38, 377-383.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Laur CV, McNicholl T, Valaitis R, Keller HH (2017) Malnutrition or frailty? Overlap and evidence gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of frailty and malnutrition. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 42, 449-458.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lim ML, Yong BYP, Mar MQM, Ang SY, Chan MM, Lam M, Chong NCJ, Lopez V (2018) Caring for patients on home enteral nutrition: reported complications by home carers and perspectives of community nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27, 2825-2835.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McDonald S, Elliott JH, Green S, Turner T (2019) Towards a new model for producing evidence-based guidelines: a qualitative study of current approaches and opportunities for innovation among Australian guideline developers. F1000Research 8, 956.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pedrosa AL, Bitencourt L, Fróes ACF, Cazumbá MLB, Campos RGB, de Brito SBCS, Simões e Silva AC (2020) Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 11, 566212.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rapport F, Clay-Williams R, Churruca K, Shih P, Hogden A, Braithwaite J (2018) The struggle of translating science into action: foundational concepts of implementation science. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 24, 117-126.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Roberts S, Collins P, Rattray M (2021) Identifying and managing malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia in the community: a narrative review. Nutrients 13(7), 2316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Roberts S, Gomes K, Rattray M (2023) Dietitians’ perceptions of identifying and managing malnutrition and frailty in the community: a mixed-methods study. Nutrition & Dietetics 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sulo S, Riley K, Liu Y, Landow W, Lanctin D, VanDerBosch G (2020) Nutritional support for outpatients at risk of malnutrition improves health outcomes and reduces healthcare costs. Quality in Primary Care 28, 12-18.

| Google Scholar |

Swan WI, Vivanti A, Hakel-Smith NA, Hotson B, Orrevall Y, Trostler N, Beck Howarter K, Papoutsakis C (2017) Nutrition care process and model update: toward realizing people-centered care and outcomes management. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 117(12), 2003-2014.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thompson MQ, Yu S, Tucker GR, Adams RJ, Cesari M, Theou O, Visvanathan R (2021) Frailty and sarcopenia in combination are more predictive of mortality than either condition alone. Maturitas 144, 102-107.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |