The role of general practitioners in the follow-up of positive results from the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program – a scoping review

Jane Gaspar A B * , Caroline Bulsara A B , Diane Arnold-Reed C , Karen Taylor B Anne Williams D

C , Karen Taylor B Anne Williams D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

There are several studies investigating the effectiveness and participation rates of the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP), but there is limited literature pertaining to the role and processes that general practitioners (GPs) follow after a positive immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) result. The aim of this paper is to review evidence examining GP involvement in the follow-up of positive iFOBT results from the NBCSP and identify knowledge gaps.

A scoping review was undertaken involving the search of the Cochrane Library, Informit, PubMed and Scopus electronic databases. Inclusion criteria were the follow-up processes and practices by GPs subsequent to notification of a positive iFOBT from this program. Searches were limited to English and publication was from January 2006 to January 2024. A combination of keywords was used and adapted to each search engines’ requirements: general practitioner AND bowel cancer AND screening AND Australia.

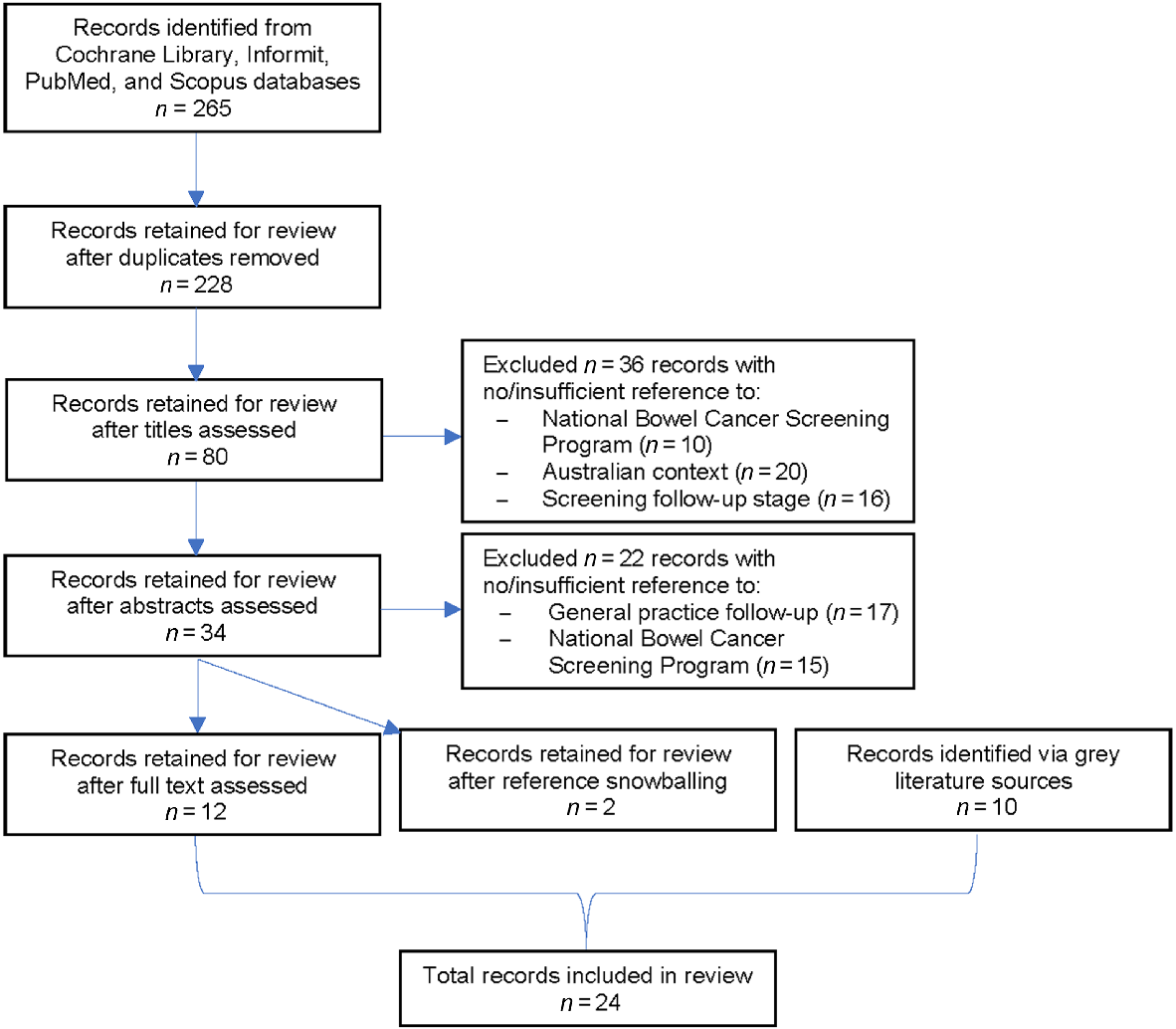

Relevant sources of evidence were reviewed, and 24 records met inclusion criteria. Results are represented across three themes: (i) screening process and GP follow-up; (ii) follow-up rates and facilitation; and (iii) recommendations for improved follow-up.

This scoping review provides insight into the central role GPs play in the implementation of the NBCSP and highlights the lack of information regarding steps taken and systems employed in general practice to manage positive iFOBTs.

Keywords: Australia, bowel cancer screening, general practice, general practitioner, iFOBT, immunochemical faecal occult blood test, National Bowel Cancer Screening Program, NBCSP, primary health care.

Introduction

Bowel cancer accounted for almost one million deaths globally in 2020, and is expected to be the fourth most diagnosed cancer and second leading cause of cancer death in Australia for 2023 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023; World Health Organization 2023). Early detection improves the chance of successful treatment and survival (Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023). The disease typically forms slowly through a series of epithelial cell mutations that form benign polyps, which may mutate into benign adenoma, and then into a malignant bowel cancer (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022). Precancerous polyps and adenomas often bleed for years before more advanced symptoms are experienced, and identifying this microscopic blood in stool is highly effective for early detection and is the aim of screening programs worldwide (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022).

The Australian Government launched the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) in 2006. Without screening, the usual care for the detection of bowel cancer is general practitioners (GPs) being alerted to the presence of a potential bowel cancer by patient reports of symptoms, and GPs may order tests in persons whom they consider to be high risk. The NBCSP entails biennial screening of asymptomatic individuals at average risk of bowel cancer via a free home sample collection kit for an immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) delivered to them in the mail (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a). Healthcare providers may also provide kits directly to eligible patients via the Alternative Access to Kits Model, which facilitates uptake among those who require support to participate (National Cancer Screening Register 2022).

From 1 July 2024, the eligible screening age for the NBCSP was lowered from 50 to 45 years, with 45- to 49-year-olds able to request their first kit from the National Cancer Screening Register1 (NCSR) or a GP, and eligible 50- to 74-year-olds continuing to receive a kit in the mail biennially, or from a GP (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a). Test results are sent to participants and, if nominated, their GPs (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b). The screening pathway comprises elements that are the responsibility of the Australian Government and of ‘usual care’ services that are delivered by public and private healthcare providers, such as GPs and hospitals (Fig. 1) (Australian Department of Health 2016; Doherty et al. 2021).

National Bowel Cancer Screening Program participant pathway showing Participant Follow-Up Function (Doherty et al. 2021). GP, general practitioner; iFOBT, immunochemical faecal occult blood test; NBCSP, National Bowel Cancer Screening Program; PFUF, participant follow-up function.

Within the Australian healthcare system, GPs are typically the initial point of contact for those seeking medical attention and, as the primary source of medical referrals, bear the responsibility of facilitating patient access to specialists (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2019; Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024c). It is advised that those with a positive iFOBT result from the NBCSP be referred for further diagnostic investigation, typically colonoscopy (Australian Department of Health 2017; Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023). As such, GPs are the ideal medical professional to encourage participation and support participants in the NBCSP (Christou et al. 2010; Bobridge et al. 2013; Dawson et al. 2017; Dodd et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2020).

Review objective

Scoping reviews are useful for mapping topics that have not been comprehensively investigated and for analysing knowledge gaps and discovering future research initiatives (Munn et al. 2018). The objective of this review was to review evidence examining GP involvement in the follow-up of positive iFOBT results from the NBCSP, and identify knowledge gaps.

Methods

This scoping review was performed between November 2023 and January 2024 in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute updated methodology for scoping reviews, which is based upon the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Peters et al. 2020).

Eligibility criteria

Sources of evidence are needed to pertain only to the Australian NBCSP as differences in health policies, healthcare system structures, and population demographics obscure cross-country comparisons of screening programs. Records are needed to refer specifically to steps performed by GPs from the time of notification of a positive result until the NBCSP participant is/is not referred for a colonoscopy.

Sources of evidence

Scoping reviews comprise a comprehensive search strategy of both published and grey literature2 to identify primary sources of evidence (Peters et al. 2024). As such, clinical guidelines; quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies; opinion papers; case studies; analytical and descriptive studies; government and NBCSP-specific records that were written in English and produced from 2006 were considered for inclusion. Citation snowballing was performed whereby references of included literature were screened for additional sources of evidence.

Search strategy

Lead author (JG) searched the Cochrane Library, Informit, PubMed, and Scopus bibliographic databases for literature published between January 2006 until January 2024. Keywords searched for across all fields included: ‘general practitioner’ AND ‘bowel cancer’ AND screening AND Australia. The search strategy was adapted for use with each database (Table 1).

| Number | Search term/combination | |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (“general practitioners”[MeSH Terms] OR (“general”[All Fields] AND “practitioners”[All Fields]) OR “general practitioners”[All Fields] OR (“general”[All Fields] AND “practitioner”[All Fields]) OR “general practitioner”[All Fields] | |

| #2 | “intestinal neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR (“intestinal”[All Fields] AND “neoplasms”[All Fields]) OR “intestinal neoplasms”[All Fields] OR (“bowel”[All Fields] AND “cancer”[All Fields]) OR “bowel cancer”[All Fields] | |

| #3 | “diagnosis”[MeSH Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “screening”[All Fields] OR “mass screening”[MeSH Terms] OR (“mass”[All Fields] AND “screening”[All Fields]) OR “mass screening”[All Fields] OR “early detection of cancer”[MeSH Terms] OR (“early”[All Fields] AND “detection”[All Fields] AND “cancer”[All Fields]) OR “early detection of cancer”[All Fields] OR “screen”[All Fields] OR “screenings”[All Fields] OR “screened”[All Fields] OR “screens”[All Fields] | |

| #4 | “australia”[MeSH Terms] OR “australia”[All Fields] OR “australia s”[All Fields] OR “australias”[All Fields] | |

| #5 | 2006/1/1:2024/1/1[pdat] | |

| #6 | english[Filter] | |

| #7 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 AND #6 |

Selection of sources of evidence, information charting, and synthesis

Search results were collated, and duplicate records removed. Titles and abstracts of the remaining records were reviewed for relevance to the study objective; that is, records were considered for inclusion if they offered insight into specific processes undertaken within the general practice setting to manage positive iFOBTs from the NBCSP. Given the broad range of articles included, quality of the evidence quality assessments were not undertaken. Titles and abstracts of literature to be included were reviewed for relevance by a second author (CB or DAR). Where there was disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion between the three reviewing authors (JG, CB, and DAR). Lead author (JG) extracted and synthesised information from the final selection of records (Table 2).

| Author(s) (Year) | Title | Record classification | Record description | Relevant objective(s)/finding(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Department of Health (2016) | NBCSP – Quality Framework | Grey literature | NBCSP framework | Chart the desired quality outcomes for the different elements of the NBCSP and the actions required for these to be achieved. | |

| Australian Department of Health (2017) | NBCSP: policy framework phase four (2015–2020) | Grey literature | NBCSP framework | Outline the policy framework of the fourth phase of the NBCSP, including key roles of GPs. | |

| Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) | NBCSP Results notification letter – positive | Grey literature | NBCSP participant information | Provide participants with results of their iFOBT and advice of GP involvement. | |

| Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) | The role of health professionals in the NBCSP | Grey literature | NBCSP information for medical professionals | Outline ways in which health professionals support the NBCSP and those participating in the program. | |

| Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) | NBCSP: monitoring report 2023 | Grey literature | NBCSP data monitoring | Monitor NBCSP data based on key performance indicators between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2022. | |

| Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2024b) | NBCSP Participant Screening Pathway | Grey literature | NBCSP participant information | Chart the pathway of participants through the NBCSP and the points of clinical interaction with the GP. | |

| Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2025) | NBCSP Participant details form | Grey literature | NBCSP participant form | Form completed by participants to provide their details to the NCSR, including their nominated GP. | |

| Bobridge et al. (2013) | The NBCSP: consequences for practice | Journal article | Retrospective review of patient case notes | Review colonoscopy wait-time, quality of documentation, and surveillance activities for NBCSP participants. GPs should familiarise themselves with screening guidelines and ensure their own recall systems are activated and surveillance intervals appropriate. | |

| Brown et al. (2020) | Patients’ views on involving general practice in bowel cancer screening: a South Australian focus group study | Journal article | Phenomenological analysis of qualitative focus group data | Explore patients’ experiences of bowel cancer screening and its promotion and perspectives on possible input from general practice. GPs play a key role in NBCSP uptake, but their multiple clinical and administrative tasks mean better engagement models are needed to ensure program effectiveness, efficiency, and quality. | |

| Brown et al. (2019) | Patient perspectives on colorectal cancer screening and the role of general practice | Journal article | Interpretative phenomenological analysis of semi-structured interviews | Explore patient perspectives on colorectal cancer screening and the potential role for general practice. Participation would be improved with increased GP involvement, general practice engagement, and patient education. | |

| Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party (2023) | Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer: population screening | Grey literature | Clinical practice guidelines | Provide information and recommendations to guide practice across the continuum of cancer care and provide an evidence base for the NBCSP. NBCSP participants with positive iFOBT results should be referred for follow-up investigation as soon as possible. | |

| Christou et al. (2010) | Australia’s NBCSP: does it work for Indigenous Australians? | Journal article | Literature review | Examine discrepancies in NBCSP screening among Australian population groups. A more community-based approach and better integration into primary health care would improve Indigenous participation in the NBCSP. | |

| Clarke et al. (2019) | Time to colonoscopy for patients accessing the direct access colonoscopy service compared to the normal service in Newcastle, Australia | Journal article | Quantitative analysis of prospectively maintained databases | Examine the effect of the DACS to colonoscopy wait-time for positive iFOBT patients. DACS reduces time to colonoscopy, but the hospital service is unable to influence time between notification of positive iFOBT and GP consultation, or directly influence a GP’s decision to refer. | |

| Dawson et al. (2017) | General practitioners’ perceptions of population-based bowel screening and their influence on practice: a qualitative study | Journal article | Thematic analysis of qualitative interviews | Examine how GPs’ perceptions of screening influence their attitudes to and promotion of iFOBTs and identify ways to enhance the GP role. GPs’ perceptions of screening impacts clinical practice and use of iFOBT but could be improved with emphasising benefits of iFOBTs and engaging GPs in promotion of screening. | |

| Dodd et al. (2019) | Testing the effectiveness of a general practice intervention to improve uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial | Journal article | Randomised controlled trial | Test the effect of an intervention with point-of-care FOBT provision, printed screening advice, and GP endorsement has on self-reported FOBT uptake. Multicomponent intervention delivered in general practice significantly increased self-reported FOBT uptake in those at average risk of CRC. | |

| Doherty et al. (2021) | Review of Phase Four of the NBCSP | Grey literature | NBCSP evaluation | Assess the appropriateness, fidelity, awareness and adoption, effectiveness, efficiency of the fourth phase of the NBCSP. | |

| Foreman (2009) | Bowel cancer screening: a role for general practice | Journal article | Literature review | Examine the role of GPs in the NBCSP. GP roles include encouraging participation, managing positively screened participants, and providing referral information. | |

| Holden et al. (2020) | From participation to diagnostic assessment: a systematic scoping review of the role of the primary healthcare sector in the NBCSP | Journal article | Systematic scoping review | Review current evidence to inform strategies that better engage the PHC sector in organised CRC screening programs. Better integration of population-based screening programs into existing primary care services can be achieved through targeting preventive and quality care interventions along the entire screening pathway. | |

| Holden et al. (2021) | General practice perspectives on a bowel cancer screening quality improvement intervention using the consolidated framework for implementation research | Journal article | Deductive thematic analysis of qualitative focus group data | Explore contextual factors of and barriers to the implementation of a CRC-QI intervention across different practice settings. Better engage GPs in NBCSP through improvements to the NCSR and practice incentive programs. | |

| Hooi and St John (2019) | The NBCSP: time to achieve its potential to save lives | Journal article | Critical review of program data | Analyse the implementation and outcomes of the NBCSP to date. Success of the NBCSP is founded on strong evidence but improvements are needed in outcomes data capture, timely colonoscopy access, and participation rates. | |

| McIntosh et al. (2023a) | Increasing bowel cancer screening using SMS in general practice: the SMARTscreen trial | Journal article | Cluster randomised controlled trial | Test efficacy of sending SMSs to patients due to receive the NBCSP kit on NBCSP uptake compared to ‘usual care’. Multi-intervention SMSs sent from general practice increases patient participation in the NBCSP. | |

| Parkin et al. (2018) | Colorectal cancer screening in Australia: an update | Journal article | Literature review | Summarise NHMRC’s recommendations for colorectal cancer screening, which includes the use of iFOBTs, risk stratification for those with a family history, and administration of aspirin to prevent colorectal cancer. | |

| Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022 | Response to Review of Phase 4 of the NBCSP consultation 1 July | Grey literature | RACGP response letter | Provide feedback on the ‘Review of Phase Four of the NBCSP’ consultation paper. | |

| Verbunt et al. (2022) | Health care system factors influencing primary healthcare workers’ engagement in national cancer screening programs: a qualitative study | Journal article | Cross-sectional qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews | Explore factors across the environment, organisation, and care team levels of the healthcare system that influence engagement of PHCWs in the NBCSP. Engagement would be improved by practices improving recall/reminder systems, optimising PHCW’s roles, and identifying a ‘screening champion’. |

CRC, colorectal cancer; CRC-QI, colorectal cancer-quality improvement; DACS, direct access colonoscopy service; FOBT, faecal occult blood test; GP, general practitioner; iFOBT, immunochemical faecal occult blood test; NBCSP, National Bowel Cancer Screening Program; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NCSR, National Cancer Screening Register; PHC, primary healthcare; PHCW, primary healthcare workers; SMS, short message/messaging service.

Results

A total of 24 records were identified as sources of evidence in this scoping review (Fig. 2, Table 2). This included the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) endorsed Cancer Council guidelines for colorectal cancer screening; a Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP) letter of response to the review of NBCSP Phase 4; eight NBCSP records including program reports and resources; and 14 articles published in peer-reviewed journals. No systematic or scoping reviews were found on the topic. Most Australian published research focused on bowel screening generally and not the specific steps of the NBCSP or the role of GPs in the follow-up stage. Holden et al. (2020) provides a comprehensive analysis of GP involvement in bowel cancer screening but only one of 57 studies in their review was performed in Australia, and only eight examined GP involvement at the results follow-up stage.

Hereafter is a summary of findings from the literature presented across three key themes: (i) screening process and GP follow-up; (ii) follow-up rates and facilitation; and (iii) recommendations for improved follow-up.

Screening processes and GP follow-up

The screening process, as described throughout the literature, commences with a participant receiving an NBCSP kit in the mail or from a healthcare provider via the newly formed Alternative Access to Kits Model (Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023). The participant completes a Participant Detail Form and iFOBT, which is sent to a pathology laboratory for analysis (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2025). The test result (whether positive, negative, or inconclusive) is sent to the participant and his/her GP, if nominated (Australian Department of Health 2016, 2017; Brown et al. 2019). A positive result letter advises the participant to make a GP appointment within the next two weeks to discuss the result (Christou et al. 2010; Clarke et al. 2019; Hooi and St John 2019; Brown et al. 2020; Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

Once the GP is notified of a positive result, the usual care phase commences and the GP is expected to: (i) consult the participant within two weeks of receiving notification of a positive iFOBT; (ii) refer the participant for colonoscopy; and (iii) notify the NCSR of the follow-up diagnostic assessment (Australian Department of Health 2016; Hooi and St John 2019; Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2023). With regards to mode of follow-up contact, a recent systematic review uncovered how GPs in different countries utilised text messaging, GP-endorsed mail-outs, and automated telephone calls to remind patients to complete population screening-based iFOBTs (Holden et al. 2020). However, no studies were found that specifically examined communication mechanisms, clinical software, practice staff involved in the follow-up and recall of positively screened participants of the Australian NBCSP.

As per the Cancer Council guidelines, GPs are expected to refer eligible, positively screened participants for further diagnostic assessment via colonoscopy (Bobridge et al. 2013; Dawson et al. 2017; Parkin et al. 2018; Clarke et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2020; Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023; Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b). The most recent NBCSP monitoring report found 85.5% of positively screened participants had a colonoscopy, and scopes were typically performed within 58 days of a positive screening result, which falls within the colorectal cancer population screening guideline recommendation of 120 days for risk minimisation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023; Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023).

General practitioners are encouraged to register their patients’ screening details and outcomes with the NCSR by fax or electronic submission (Foreman 2009; Australian Department of Health 2016; Doherty et al. 2021). This step is voluntary and literature notes that underreporting does occur (Doherty et al. 2021; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). The Healthcare Provider (HCP) Portal was launched in 2020 to facilitate reporting by linking to the NCSR and enabling the digital sharing of screening data, thereby reducing the need for paper-based reporting (Doherty et al. 2021). The HCP is expected to improve reporting of screening activity, participation rates, and communication throughout the program but its implementation and functionality is yet to be comprehensively evaluated (Doherty et al. 2021).

Follow-up rates and facilitation

In the most recent review of the NBCSP, analysis of NCSR data extracted from November 2019 to December 2020 found approximately 80% of positively screened participants attended a GP appointment, and 71% of recorded appointments occurred within 14 days of results notification (Doherty et al. 2021). Lowest follow-up rates are among individuals with a disability, those from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, and those residing in lower socioeconomic areas (Christou et al. 2010; Doherty et al. 2021; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). Poor follow-up among Indigenous Australians may be attributed to individual, access, economic, and provider-related barriers such as: poor awareness of bowel cancer and knowledge of screening; frequent moving and changing of address; costs and logistics of attending GP appointments; and lack of coordinated, culturally appropriate services, resources, and information (Christou et al. 2010).

The NBCSP implements a series of reminders as depicted in the Participant’s Screening Pathway (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b), along with a Participant Follow-Up Function (PFUF) (Fig. 1) to encourage participants to attend GP appointments (Australian Department of Health 2017). Participants and GPs receive reminder letters and phone calls from PFUF officers if no record of GP activity is registered with the NCSR (Fig. 1). Despite these program initiatives, it remains best practice for GPs to guide follow-up processes with their patients (Foreman 2009; Holden et al. 2021).

Recommendations for improved follow-up

Investigations into factors influencing engagement of Australian primary healthcare workers (PHCW) in bowel and breast cancer screening programs found that most do not utilise recall and reminder systems and assumed these to be the remit of screening programs (Dodd et al. 2019; Verbunt et al. 2022). Some studies recommended these automated recalls and prompts be established and managed by practice nurses and non-medical clinic staff, rather than typically time-poor GPs (Dawson et al. 2017; Verbunt et al. 2022). The RACGP advised any follow-up processes be aligned with existing, integrated clinical recalls, and for patient communication systems and patient-endorsed short message services (SMS) alongside email messaging to be included to increase the likelihood of making contact with a patient (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022).

Along these lines, the SMARTscreen trial assessed whether screening uptake could be improved if patients due to receive NBCSP kits were first sent a personalised SMS from their general practice clinic endorsing the kit, a motivational narrative video, an instructional video, and a link to more information (McIntosh et al. 2023a). Results found participation increased by 16.5% (95% confidence interval = 2.02–30.9%) among those who received these prior communications compared to those who did not (McIntosh et al. 2023a). A subsequent three-arm stratified cluster randomised controlled trial titled ‘SMARTERscreen’ is currently underway and aims to compare participation rates among patients who receive: (i) an SMS with an encouraging message from their general practice clinic; (ii) the same SMS with weblinks to additional motivational and instructional videos; or (iii) no additional communications prior to receiving their NBCSP kit (McIntosh et al. 2023b).

The RACGP proposed positively screen participants be automatically referred for appropriate follow-up investigation, as occurs for imaging in the Australian BreastScreen program (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022). However, bypassing general practice clinics may impact best practice obligations of GPs (Foreman 2009; Holden et al. 2021). Instead, offering financial and/or practice accreditation-based incentives for uploading iFOBT results to the NCSR or optimising GP recall systems for the program could help cover practice costs and motivate GPs and practice staff to prioritise NBCSP participation (Christou et al. 2010; Dodd et al. 2019; Holden et al. 2020, 2021; Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022; Verbunt et al. 2022).

Discussion

This scoping review was undertaken to consider evidence examining GP involvement in the follow-up of positive iFOBTs from the NBCSP and uncovered the integral position they hold throughout the program. The NBCSP has the potential to considerably reduce bowel cancer prevalence and mortality with the efficient transition of positively screened participants from the point of engagement to that of diagnostic assessment (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). Statistics show individuals with bowel cancer detected through the program are more likely to be diagnosed with less-advanced cancer and have a lower risk of mortality (9.6%) compared to those diagnosed outside of the NBCSP (23.8%) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018). However, the structure of the Australian healthcare system means this progression is reliant upon GPs consulting positively screened participants within the suggested two weeks and referring them onto colonoscopy (Australian Department of Health 2016). The following discussion draws attention to several such factors related to the general practice setting and the NBCSP and acknowledges the instrumental part played by GPs in each of these.

Although PFUF officers may encourage participants to attend GP appointments, it is the domain of GPs to then refer positively screened participants for further diagnostic investigation via colonoscopy, if appropriate (Foreman 2009; Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2019). Although the accepted benchmark is 30 days from GP referral to colonoscopy, NHMRC advises participants undergo the procedure as soon as possible to reduce psychological distress and within 120 days to minimise risk of advancing the severity of disease, if cancer is present (Clarke et al. 2019; Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party 2023).The timing of a positively screened participant’s follow-up appointment with a GP and the efficiency of the subsequent referral is key to the colonoscopy being performed within this desired timeframe.

General practitioners are expected to report NBCSP participant information to the NCSR, which relies upon voluntary provision of clinical data to work effectively. Participant reminders and program monitoring data are potentially inaccurate if clinical interactions are not reported (Doherty et al. 2021; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). The HCP Portal was launched to support identifying participants, accessing screening histories, and reporting by allowing clinical data to be shared between practices and the NCSR at the time of consultation via a desktop integration portal for selected clinic software (Australian Department of Health 2017; Doherty et al. 2021; Verbunt et al. 2022). Data gaps continue to exist and are often attributed to poor integration between practice software and the NCSR and GP lack of time (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022; Verbunt et al. 2022).

The provision of financial incentives has been posited as a means of encouraging the promotion of bowel cancer screening within the general practice setting and the reporting of data to the NCSR by GPs (Christou et al. 2010; Dodd et al. 2019; Holden et al. 2020, 2021; Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022; Verbunt et al. 2022). Financial reimbursements were previously given to GPs for reporting screening data to the NCSR but were removed in 2021 to coincide with the transition from paper-based reporting to digital reporting via the HCP Portal (Doherty et al. 2021). Clinicians and peak body organisations objected to this change citing its failure to acknowledge the time taken to submit information online and suggesting it would in fact lead to an increase in non-submissions and subsequent data gaps (Doherty et al. 2021).

None of the research studies included in this review specifically investigated Australian GPs’ follow-up procedures of NBCSP iFOBT results (Table 1). Furthermore, the authors were unable to locate any grey literature that investigated the timing of positively screened participants being contacted by clinic staff, the method by which participants were contacted, the urgency of the appointment to discuss their positive result with their GPs, and/or the software employed by clinics to book and monitor this appointment. Research into specific steps taken and systems employed in general practice clinics following a positive iFOBT may help to implement better support of the transition from participation to diagnostic investigation for those who participate in the NBCSP.

Conclusion

This first review of sources of evidence that describe GP procedures following a positive iFOBT result has indicated a dearth of information on the usual care process for participants and GPs. General practitioners play a pivotal role in the success of the NBCSP, further enhanced by the implementation of the Alternative Access to Kits Model and the on-demand kit requests for 45- to 49-year-old screening cohort, which generate additional layers of patient engagement and management by GPs. General practitioners’ prioritisation of participation, follow-up practices, and the value they assign to bowel screening are key driving forces in the effectiveness of the NBCSP. Clarity on factors that support and hinder this follow-up process is essential. Further research would contribute towards improving efficacy of the NBCSP and a better understanding of the ways in which work within the general practice setting supports screening pathways.

Data availability

Data and methods used for this scoping review are detailed in the manuscript. Records reviewed were extracted from various sources that are accessible through the relevant databases or repositories.

Conflicts of interest

CB, JG, and DAR received a grant from North Metropolitan Health Service. North Metropolitan Health Service had no input in the design and conduct of the study or interpretation of results. KT was employed by North Metropolitan Health Service at the time of the study. KT and AW were members of the Project Steering Committee established for the study. JG and DAR received financial support, and CB, DAR, and JG received conference support through the grant.

Declaration of funding

This project was funded by the State of Western Australia acting through the North Metropolitan Health Service.

References

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) National bowel cancer screening program results notification letter – positive. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019/09/national-bowel-cancer-screening-program-results-notification-letter-positive_0.pdf [Accessed 24 October 2023]

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) The role of health professionals in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-bowel-cancer-screening-program/managing-bowel-screening-for-participants/the-role-of-health-professionals-in-the-national-bowel-cancer-screening-program#role-of-general-practitioners-and-practice-nurses [Accessed 21 November 2023]

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2024a) About the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-bowel-cancer-screening-program/about-the-national-bowel-cancer-screening-program [Accessed 27 May 2024]

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2024b) National bowel cancer screening program participant screening pathway. Australian Department of Health, Canberra. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-06/national-bowel-cancer-screening-program-participant-screening-pathway.pdf [Accessed 24 July 2024]

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2024c) The role of a GP. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra. Available at https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/the-role-of-a-gp [Accessed 14 January 2024]

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2025) National bowel cancer screening program participant details form. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-02/national-bowel-cancer-screening-program-participant-details-form.pdf [Accessed 26 February 2025]

Bobridge A, Cole S, Schoeman M, Lewis H, Bampton P, Young G (2013) The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: consequences for practice. Australian Family Physician 42, 141-145.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brown LJ, Roeger SL, Reed RL (2019) Patient perspectives on colorectal cancer screening and the role of general practice. BMC Family Practice 20, 109.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brown L, Moretti C, Roeger L, Reed R (2020) Patients’ views on involving general practice in bowel cancer screening: a South Australian focus group study. BMJ Open 10, e035244.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Party (2023) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer: population screening. (Ed. M Goulding). Cancer Council Australia, Sydney. Available at https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/j1Q1Xj [accessed 18 January 2024]

Christou A, Katzenellenbogen JM, Thompson SC (2010) Australia’s National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: does it work for Indigenous Australians? BMC Public Health 10, 373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clarke L, Pockney P, Gillies D, Foster R, Gani J (2019) Time to colonoscopy for patients accessing the direct access colonoscopy service compared to the normal service in Newcastle, Australia. Internal Medicine Journal 49, 1132-1137.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dawson G, Crane M, Lyons C, Burnham A, Bowman T, Perez D, Travaglia J (2017) General practitioners’ perceptions of population based bowel screening and their influence on practice: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 18, 36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dodd N, Carey M, Mansfield E, Oldmeadow C, Evans T-J (2019) Testing the effectiveness of a general practice intervention to improve uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 43, 464-469.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Doherty N, Kilroy G, Russell-Bennett R, McGraw J (2021) Review of phase four of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra. Available at https://eprints.qut.edu.au/232121/ [Accessed 21 November 2023]

Foreman L (2009) Bowel cancer screening – a role for general practice. Australian Family Physician 38, 200-203.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Holden CA, Frank O, Caruso J, Turnbull D, Reed RL, Miller CL, Olver I (2020) From participation to diagnostic assessment: a systematic scoping review of the role of the primary healthcare sector in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Australian Journal of Primary Health 26, 191-206.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Holden CA, Turnbull D, Frank OR, Olver I (2021) General practice perspectives on a bowel cancer screening quality improvement intervention using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Public Health Research & Practice 31, 30452016.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hooi C, St John J (2019) The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: time to achieve its potential to save lives. Public Health Research & Practice 29, 2921915.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McIntosh JG, Jenkins M, Wood A, Chondros P, Campbell T, Wenkart E, O’Reilly C, Dixon I, Toner J, Martinez Gutierrez J, Govan L, Emery JD (2023a) Increasing bowel cancer screening using SMS in general practice: the SMARTscreen trial. British Journal of General Practice 74, e275-e282.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McIntosh JG, Emery JD, Wood A, Chondros P, Goodwin BC, Trevena J, Wilson C, Chang S, Hocking J, Campbell T, Macrae F, Milley K, Lew J-B, Nightingale C, Dixon I, Castelli M, Lee N, Innes L, Jolley T, Fletcher S, Buchanan L, Doncovio S, Broun K, Austin G, Jiang J, Jenkins MA (2023b) SMARTERscreen protocol: a three-arm cluster randomised controlled trial of patient SMS messaging in general practice to increase participation in the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Trials 24, 723.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18, 143.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parkin CJ, Bell SW, Mirbagheri N (2018) Colorectal cancer screening in Australia: an update. Australian Journal of General Practice 47, 859-863.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H (2020) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18, 2119-2126.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H (2024) Chapter 10: Scoping Reviews. In ‘JBI manual for evidence synthesis’. (Eds E Aromataris, C Lockwood, K Porritt, B Pilla, Z Jordan) 10.46658/JBIMES-24-09

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2019) Referring to other medical specialists: a guide for ensuring good referral outcomes for your patients. (RACGP) Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Running%20a%20practice/Practice%20resources/Referring-to-other-medical-specialists.pdf [Accessed 18 January 2024]

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2022) Response to Review of Phase 4 of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program consultation 1 July. (RACGP) Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/getmedia/c433252f-d712-4956-8b3e-cf636d19901f/Response-to-Review-of-Phase-4-of-the-National-Bowel-Cancer-Screening-Program-consultation_1-July.pdf.aspx [Accessed 29 November 2023]

Verbunt E, Boyd L, Creagh N, Milley K, Emery J, Nightingale C, Kelaher M (2022) Health care system factors influencing primary healthcare workers’ engagement in national cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 46, 858-864.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

World Health Organization (2023) Colorectal cancer. (WHO) Available at https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-type/colorectal-cancer/

Footnotes

1 NCSR contains electronic records for all individuals invited to participate in the NBCSP; offers digital infrastructure for collecting, storing, analysing, and reporting screening data; facilitates mailing of test kits, participant support, and clinical decision-making (Doherty et al. 2021).

2 ‘Grey literature is essentially anything that is not controlled by the traditional, usually peer-reviewed, academic publishing market’ (Bonato 2018).