Access to general practice for preventive health care for people who experience severe mental illness in Sydney, Australia: a qualitative study

Catherine Spooner A * , Peri O’Shea

A * , Peri O’Shea  A , Karen R. Fisher

A , Karen R. Fisher  B , Ben Harris-Roxas

B , Ben Harris-Roxas  C , Jane Taggart

C , Jane Taggart  A , Patrick Bolton

A , Patrick Bolton  A D and Mark F. Harris

A D and Mark F. Harris  A

A

A

B

C

D

Abstract

People with lived experience of severe mental illness (PWLE) live around 20 years less than the general population. Most deaths are due to preventable health conditions. Improved access to high-quality preventive health care could help reduce this health inequity. This study aimed to answer the question: What helps PWLE access preventive care from their GP to prevent long-term physical conditions?

Qualitative interviews (n = 10) and a focus group (n = 10 participants) were conducted with PWLE who accessed a community mental health service and their carers (n = 5). An asset-based framework was used to explore what helps participants access and engage with a GP. A conceptual framework of access to care guided data collection and analysis. Member checking was conducted with PWLE, service providers and other stakeholders. A lived experience researcher was involved in all stages of the study.

PWLE and their carers identified multiple challenges to accessing high-quality preventive care, including the impacts of their mental illness, cognitive capacity, experiences of discrimination and low income. Some GPs facilitated access and communication. Key facilitators to access were support people and affordable preventive care.

GPs can play an important role in facilitating access and communication with PWLE but need support to do so, particularly in the context of current demands in the Australian health system. Support workers, carers and mental health services are key assets in supporting PWLE and facilitating communication between PWLE and GPs. GP capacity building and system changes are needed to strengthen primary care’s responsiveness to PWLE and ability to engage in collaborative/shared care.

Keywords: community mental health: services, delivery of health care: integrated, health services: accessibility, health services: needs and demands, patient care: team, preventive health services, preventive medicine, primary health care.

Introduction

A severe mental illness (SMI) is one ‘which is severe in degree and persistent in duration, that causes a substantially diminished level of functioning in the primary aspects of daily living’ (Whiteford et al. 2017). SMI includes psychotic illnesses (primarily schizophrenia), severe depression and severe anxiety disorders. It affects about 3% of Australians (Whiteford et al. 2017).

Globally, people with lived experience of SMI (PWLE) have poorer physical health and a shorter life expectancy than the general population (Liu et al. 2017; Firth et al. 2019). The size of the gap varies with different studies and there is some evidence that it is increasing (Liu et al. 2017; Firth et al. 2019). Most deaths are due to preventable diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are more prevalent among PWLE than the general population (Liu et al. 2017; Firth et al. 2019).

Improving access of PWLE to preventive care could improve health outcomes (Liu et al. 2017; Firth et al. 2019). Preventive health care includes the management of risk behaviours and physiological risk factors and the early detection of disease based on evidence-based guidelines (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2018). General practice is a key provider and coordinator of preventive health services in Australia and internationally.

Access to effective preventive health care is a challenge, even for the general population, particularly due to the costs of many health services and the disjointed health system that makes referral and follow-up difficult (Harris and Lloyd 2012). Previous research has identified barriers for PWLE accessing general practice include individual, provider and system issues (Liu et al. 2017; Firth et al. 2019). Individual issues include cognitive difficulties, low health literacy and low income. Provider issues include stigma, diagnostic overshadowing and poor communication. System issues relate to the fragmented healthcare system (Happell et al. 2019). Some facilitators of access for PWLE include improving GP–PWLE interactions, support people (including carers) and collaborative care models (Ewart et al. 2016; Happell et al. 2017; Stumbo et al. 2018; Firth et al. 2019).

There is currently little research about consumer and carer perspectives to inform interventions that might improve access by PWLE to general practice for preventive care. This study explored the experiences and perspectives of PWLE and carers in accessing primary health care (PHC) in Sydney, Australia.

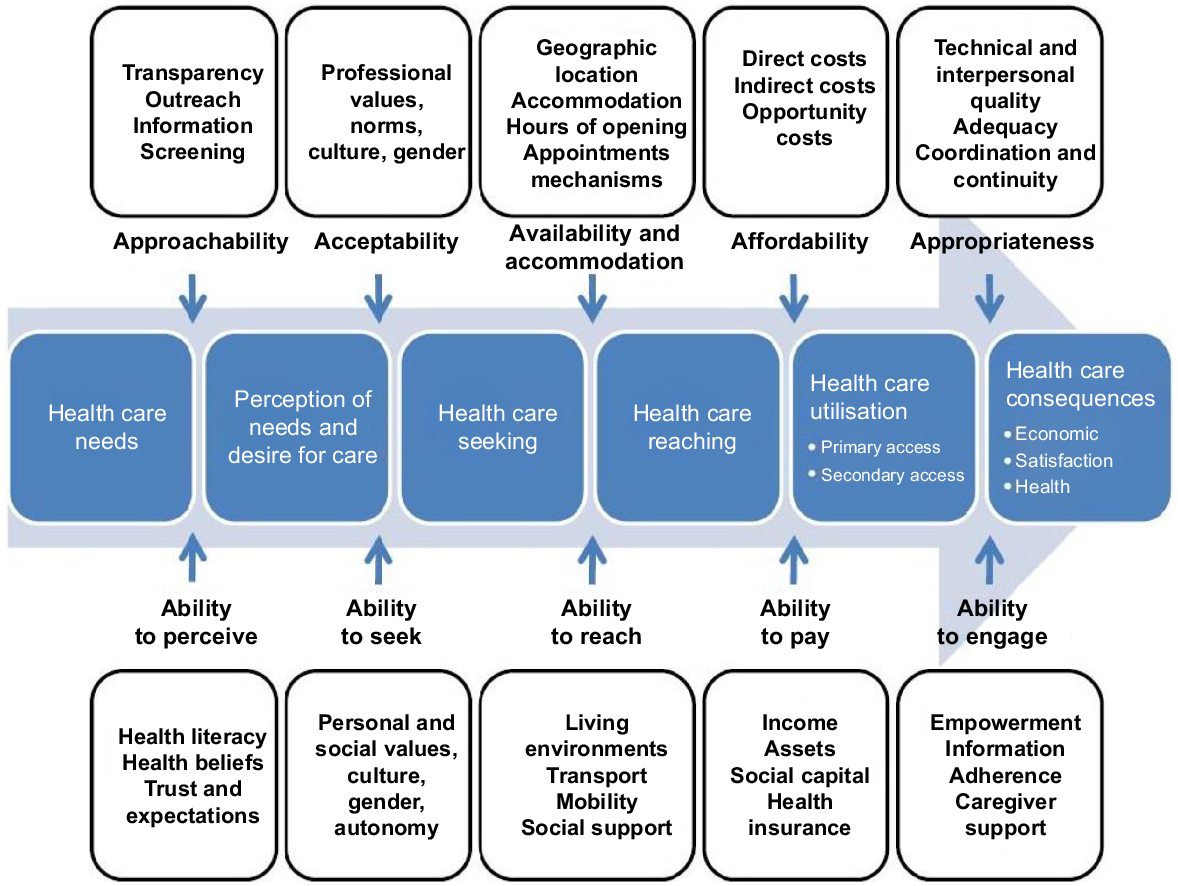

A conceptual framework for access to health care was developed by Levesque, Harris and Grant (‘the access framework’, Fig. 1) (Levesque et al. 2013). The framework describes access across six steps from identifying the need for health care to experiencing the consequences of health care. Each step is influenced by provider factors (approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability and appropriateness) and consumer abilities (to perceive, to seek, to reach, to pay and to engage).

The objective of this study was to identify the factors that help PWLE access preventive care from their GP to prevent long-term physical conditions.

Method

Study design

This study used qualitative methods including individual interviews and a focus group with PWLE and carers. The project used an asset-based framework (strengths of the person, community and agencies) to explore what PWLE value in their relationship with their GP (Cooperrider and Whitney 1999). One of the authors (PO) is a lived experience researcher and was involved in study design, implementation, analysis and reporting.

Sample

Consumer participants were PWLE who met the following criteria:

Diagnosis: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression or anxiety disorder or other serious mental health disorder

Disability: the disorder causes significant disability or difficulties with daily function

Duration: the disorder has lasted for a significant duration, usually at least two years.

The sample of carers were family or the significant other of a PWLE.

Consumers and carers were recruited from a publicly funded Mental Health Service (MHS) and a non-government community-managed organisation (CMO). The MHS linked and supported consumers to access an appropriate GP, which permitted the study to investigate positive experiences of access to a GP. Most consumer participants in this study had support workers or carers.

Ten consumers participated in individual interviews and ten in a focus group discussion. Three had support workers who participated in the focus group discussions.

Five telephone interviews were conducted with primary carers or family members.

Data collection

PWLE were interviewed face-to-face in their homes, at their MHS or at another place they chose (e.g. a park or shopping centre). Interviews were conducted by one or two researchers. Three of the interviews included a support worker who contributed to data. The focus group was held at the MHS with two researchers facilitating. The family carer interviews were conducted via telephone by one researcher.

Consistent with an asset-based approach (Cooperrider and Whitney 1999), the interviews and workshop focused on good experiences and preferences for positive GP connections to inform future service design improvement.

Data analysis

The consultations were audio recorded and transcribed. A Thematic Qualitative analysis was conducted using the access framework (Levesque et al. 2013). Initial results were presented to and discussed with the research team and a stakeholder group in a half-day workshop to member check the findings and the team’s interpretation of the findings. Stakeholders comprised PWLE (including participants from the consultations), carers, MHS providers, Primary Health Networks (PHNs), GPs and others locally engaged in providing health services for PWLE. All data were then subject to in-depth analysis by the study team using an iterative process of questioning initial results and their relevance to the access framework and returning to the data for confirmation.

Results

Results from discussions with PWLE are presented using the domains of the access framework (consumer abilities and provider capabilities). PWLE and carers reported similar experiences within this framework.

Consumer abilities

Generally, participants reported a good understanding of the need for preventive health care and sought information from their GP and through other sources such as the internet.

I had blood tests with this doctor but no women’s PAP smears or anything like that. … No, not at the moment, but I’m going to ask. (PWLE)

They reported their ability to perceive physical healthcare needs was impeded when they were unwell with acute mental illness symptoms. People sometimes needed support to perceive they needed health care.

I said, ‘You’ve got to see the doctor about this.’ … So it was actually really tricky for [the consumer] to come to that awareness herself about ringing the doctor because of her [mental health] conditions being bad. (Support worker during interview with PWLE)

Most participants said they could make an appointment to see a GP most of the time. Some said that acute mental illness symptoms, previous negative experiences, unexpected changes of personnel or processes or anxiety about the possibility of failure (e.g. appointments not available) thwarted their ability to seek health care.

Some participants said they found it difficult to make an appointment and that support could help to do this.

Sometimes it’s hard to … be organised enough or to know enough time when things are on and when you’ve got to book in for things. (PWLE)

I get a bit anxious if I have to wait for the receptionist to get on the line sort of thing. (PWLE)

I can ring up and make another appointment but if I can’t get to her I get upset so [my support worker] helps me. (PWLE)

Some participants said that they could make their own way to the doctor most of the time. Sometimes mental illness or other cognitive or functioning challenges impeded their ability to reach health care. Reasons participants gave included: difficulty organising and remembering appointment times, concerns about using public transport, fear of leaving home or being in a public place, cost of transport and concerns about discrimination.

Sometimes it’s hard to get to places and sometimes it’s hard to be organised enough or to know enough when things are on and when you’ve got to book in for things. (PWLE)

[I go to my GP] By train, yeah. And, sometimes, I don’t have enough money to get there. (PWLE)

It is very difficult to get him to go to the surgery [when] he feels so unwell. He doesn’t want to go outside … he certainly doesn’t want to go to the doctor. (Carer)

Most people had a support worker or a family carer to assist them to address these difficulties. Support included helping participants with organising their time and remembering appointment times, travel training to reach appointments or driving participants to appointments if they had a fear of public transport and/or needed support to manage and alleviate anxiety leading up to the appointment. Some participants had free transport to the doctor through the Australian government’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS, which funds support and other services for people with disability).

Well, because I suffer from anxiety [my support worker] … came with me to the doctor and it kind of broke that anxiety that I had someone with me, but I’m trying to do it on my own now. (PWLE)

Most participants received government benefits and had a low ability to pay fees for preventive health. Many said they would not be able to go to a doctor who did not bulk bill. The low income of most PWLE precluded people from getting necessary health care that wasn’t subsidised:

I’ve finished seeing the dentist. Well, they charge for it and that’s why. (PWLE)

Participants used Medicare, Australia’s government-funded universal health care insurance scheme, which covers primary and specialist health services, but does not include dental care.

Participants said their ability to engage can be affected by their mental illness or by concerns about discrimination (actual and perceived).

I think people with mental illnesses, we overthink everything as it is, so it doesn’t help when you’re catching on to the way someone’s treating you, like you pick up every little detail. (PWLE)

Just because we have a mental illness, it doesn’t mean we’re dumb. (PWLE)

They said they wanted to be asked about their health and sometimes did not know how to raise the issue or what to ask for. Some participants thought the doctor might not have time to discuss matters that were not immediately pressing.

Sometimes, if I feel like a doctor is too busy [to ask about other things], I will think, put the doctor first and throw it off for next time. (PWLE)

Many participants said that having a support person or family carer with them helped them to engage with their GP.

[It] helps to have one of my case manager’s or social workers there to help me explain things. (PWLE)

GP capabilities

There were no reports of GPs who promoted themselves as mental health friendly or who initiated outreach with a MHS. The MHS that assisted with recruitment to the study had initiated a link with a local medical practice and supported consumers to attend that practice.

There was little evidence of people choosing GPs because of their acceptability to PWLE – although many participants said that they would change to a doctor who ‘got it’ (understood the needs and perspective of PWLE) if they knew where to find one.

I was seeing someone at [close town to home] which I didn’t like because I didn’t think she got it, the mental health stuff. I’m seeing someone [different] now … and she’s very good. (PWLE)

Availability and accommodation factors of the GP practice were important enablers that assisted participants to seek and reach PHC. Some key elements that participants said helped them to attend and continue to attend a practice included: flexible appointment systems, timely appointments, public transport close by, appropriate waiting area, short waiting times, and longer appointment times.

[The reception staff are] pretty good to me because, sometimes, they will let me wait, just come in and wait until they have a space open … they don’t do with all their patients. (PWLE)

A few times that I went in there and walked out because of the queue. (PWLE)

He won’t wait in the waiting room, he’ll wait outside … And they know that he’s out there. So, they’ll come out to him every now and then say, oh, you know, you’re next on the list. (Carer)

Participants also gave examples of the challenges they faced when services were less accommodating or flexible.

I just worry about the other people in the [waiting] room. Well, because I get anxious … A quiet space would be good. (PWLE)

… the way they run the clinic; I’m not impressed. How you can’t get an emergency appointment and stuff, or if you’re late, or if you miss your appointment, they’re not very flexible or understanding to a sick person. (PWLE)

The participants in this study only accessed GPs who bulk billed. Some were able to access preventive programs because they were free or heavily subsidised. These included publicly funded programs such as those run by the MHS (e.g. Keeping the Body In Mind) (Curtis et al. 2016) and the hospital outpatient services (e.g. dietitians and diabetic clinics). Other preventive health services (e.g. dietician, exercise physiologists) were funded through the NDIS. The participants said that without this support they would not be able to access such services due to their inability to pay.

She just asked me what I am doing about losing weight, and I just said, going to the gym, just doing the Pilates and yoga and stuff. [NDIS support service] put me onto it. They’ve been pretty good linking me up with a few things. … [It’s] $35.00 a fortnight, which is affordable, and I can go as many times as I like, and I’m enjoying it. (PWLE)

I’m doing a variety of exercise, keep training, resistance exercise and I see an exercise physiologist … because I had NDIS funding so I could see [him] so otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to make it but he’s a very good exercise physiologist (PWLE)

GP communication and behaviour affected how well participants engaged with their GP and their care. Most PWLE reported at least one positive interpersonal experience with a GP. Many people spoke about the importance of a GP that ‘got it’. This meant GPs showing understanding of the needs of PWLE and whose communication was respectful, non-judgmental and effective e.g. asking questions, listening to the consumer and taking time to relate.

She listens a little bit more, and she’s open to talking about medications, stuff like that. Well, just that she’s more personable than a lot of the other doctors that I’ve seen. (PWLE)

Many participants had also experienced inappropriate or poor communication and engagement. Examples included GPs not listening to the person, talking about them in the third person and cutting people short,

[The GP] was just so rude that I freaked out … Just telling me to be quiet when I was trying to explain the situation, the health situation. Telling me to be quiet, and that was it, I wasn’t allowed to give him more information. (PWLE)

... when my husband came along and my GP was listening to him and not listening to me and I found that that was happening quite a lot, so I changed GPs. (PWLE)

Some gave examples of GPs making assumptions about their diagnosis and capacity based on the persons mental health history regardless of their current presentation or stated concerns – i.e. overshadowing.

I have found that GPs as soon as they hear mental health, any suggestion of mental health. It becomes all about that. Yes. And physical health is sidelined. (Carer)

Many participants said that the structure of appointment times could have a detrimental effect on communication, with doctors seeming to rush to get through the appointment within an allotted time. While most had experiences of being (or feeling) rushed some had also found a GP that took the time to fully engage with them.

… they don’t mind spending five minutes explaining something. Some doctors say, ‘look I’m busy’ and fair enough, they’ve got the privilege to do that … but if they give five minutes of their time sometimes, I really appreciate that, it’s helpful (PWLE)

Because my GP, if he’s got a patient it takes a long time, he will take that time. (PWLE)

The communication and engagement of other staff in the practice including receptionists’ interpersonal skills and the waiting environments and procedures were important to participants. Participants spoke about good and bad experiences and the need for all practice staff to be understanding, respectful and accommodating.

Sometimes, [the reception staff] can be rude … Like, you can hear them when they’re talking – everybody gets stressed out. You can hear them when they’ve got somebody on the phone, and then they put them on pause and they’re talking about them. (PWLE)

Results mapped to the access framework

The findings from the discussions with PWLE were mapped to the access framework in Fig. 2. While specific barriers and facilitators varied across the access journey, some factors were important at multiple points. Provider capabilities that helped across the journey included accommodation of the needs of PWLE and effective communication. Challenges for PWLE at multiple points of the journey were mental illness, cognitive capacity, health literacy and perceived discrimination. Low income influenced ‘ability to pay’, and supports from carers, family or the MHS helped at each stage.

Results mapped to the conceptual framework of access to health care developed (Levesque et al. 2013).

Discussion

We aimed to learn what helps PWLE access preventive care from their GP to prevent chronic ill health. The major challenges described by the PWLE in this study (mental illness, impaired cognitive capacity, perceived discrimination, low health literacy and low income) have been reported in qualitative studies (Ewart et al. 2016; Melamed et al. 2019) and international reviews (Firth et al. 2019; Thornicroft et al. 2022). However, the focus of our study was on facilitators of access. Key facilitators were people who supported access, GPs who actively supported access and provided appropriate care and affordable preventive health services. These are discussed below along with suggestions for system change to support access.

People to support access for PWLE

Navigation support from carers, support workers and the MHS was valued. All of the PWLE in this study had support to reach and engage with GPs from either NDIS-funded services, family or the MHS. Support was sometimes temporary to build the capacity and confidence of PWLE towards more independent access, consistent with mental health and NDIS best practice – supporting independence and self-determination (Brophy et al. 2022).

Not all PWLE in Australia or elsewhere have sufficient support to access preventive care. Peer workers (Cabassa et al. 2017) and carers are valuable in this role (Happell et al. 2017). NDIS has meant some PWLE have support workers who can help with access, however, the capacity of support workers to facilitate access to preventive care can be variable (Devine et al. 2022). Given their increased role in the disability support sector since NDIS began, more attention in research, policy and system reform is needed to ensure that NDIS services have capacity to support access to preventative physical health care for PWLE.

The role of the MHS in screening and other preventive health programs is well researched (Firth et al. 2019; Bartlem et al. 2020). However, the role of MHS case managers in supporting navigation is not often discussed. This could be because such a role is subsumed in discussions of coordinated/shared care. In this study, a MHS clinician supported access to a local medical practice, which assisted access for those consumers.

A gap seems to be that dedicated resources are needed for support workers who can improve access to preventive care for PWLE, especially for people who do not have carer, MHS or NDIS support.

GP capacity to provide access to appropriate care

Accommodating the needs of PWLE is about recognising the challenges faced by PWLE to access and engage in care and making adjustments to address those challenges. Participants repeatedly talked about GPs who ‘got it’. By this, they meant that the GP understood and accommodated their needs, treated them with respect and could communicate effectively with them. Evidence of good practice where needs were accommodated included minimising the wait time before an appointment, tolerance of missed appointments, having a quiet space to wait for an appointment and allowing for longer appointments so that communication is not rushed, consistent with previous research (Melamed et al. 2019).

Creating a mental-health friendly service requires changes to practice policies and capacity building within the whole general practice. Health system strain, particularly during and since COVID, has contributed to challenges for general practices (Thomas et al. 2020). Consequently, general practices require support, incentives and funding to build capacity. PHNs are well placed to provide this support. Training is needed during undergraduate medical education and continual professional development. Components of capacity building could include understanding of the needs of PWLE (as discussed above), skills in trauma-informed practice, awareness of negative effects of discrimination on health care and training in how to collaborate with other professions (Firth et al. 2019; Happell et al. 2019; Thornicroft et al. 2022). Including PWLE (e.g. patients or peer workers) to help identify issues and culturally appropriate responses can reduce staff prejudices as a result of working together (Thornicroft et al. 2022). Without system reform, it is difficult for general practices to provide person-centred care for any group with complex needs.

Affordability

The barriers to preventive care due to the participants’ low employment and income levels were raised and are discussed in the literature (Firth et al. 2019; Vereeken et al. 2023). Participants in this study with access to free preventive health programs within the mental health service valued them and said they could not afford commercial programs offering the same services. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission identified that relationships between socioeconomic disadvantage, mental health and physical health are complex and can operate synergistically to exacerbate health inequalities (Firth et al. 2019). While Australia’s Medicare insurance program improves access to GPs and a small number of health programs are provided by government health services, these are not universally available. The issues of poverty, social isolation and insecure housing, along with the other issues raised above (e.g. discrimination and the effects of mental illness) make access to preventive care very difficult.

Coordinated/shared care

Discussions with stakeholders identified that, while accessing a GP is important, preventive care of PWLE engaged with MHSs relies upon coordination over time. Recommendations for coordinated care are consistent with general principles of effective PHC as well as reviews on what is needed for PWLE (Firth et al. 2019; Calder et al. 2022). Primary care is considered the optimal setting for coordinating complex chronic conditions (Firth et al. 2019). Specifically, shared care between GPs and MHSs includes agreements about roles and tasks, with ongoing communication and sharing of information to achieve continuity of care (‘RACGP – Shared Care Model between GP and non-GP specialists for complex chronic conditions’; RACGP 2023).

Coordination is a challenge for PHC in the fragmented, fee-for-service health system of Australia and many other countries (Bartlem et al. 2020). GP Team Care funding arrangements have not been sufficient for GPs to provide preventive care for disadvantaged groups to address health inequities (Harris and Harris 2023). Other challenges include bureaucratic barriers regarding sharing records, governance and funding issues (Firth et al. 2019).

Numerous models of shared care have been trialled (Parker et al. 2023). Facilitators of shared care and local initiatives can be effective where there are shared goals, mutual respect and a willingness to trial tailored solutions for each context. These innovations will need to engage local consumers, providers and other stakeholders to ensure appropriate tailoring of initiatives.

In Australia, PHNs are funded to plan, coordinate and commission services to achieve integrated care for people with severe mental illness (Primary Mental Health Care Services for People With Severe Mental Illness 2019). PHNs could drive change in improving the coordination and quality of physical health care for PWLE via, for example, their GP support activities and commissioning services to support coordination and navigation.

Conclusion

The PWLE in this study reported that they wanted GPs who understood their needs, support to navigate to and engage with preventive health providers and affordable (if not free) preventive health services. Until the health system is able to provide equitable, integrated, appropriate and continuing preventive health care, PWLE need to be supported to access and engage with GPs. GPs can play an important role facilitating access and communication with PWLE but need support to do so, particularly in the context of current demands in the Australian health system. Support workers, carers and mental health services are key assets in supporting PWLE and facilitating communication between PWLE and GPs. GP capacity building and system changes are needed to strengthen primary care’s responsiveness to PWLE and ability to engage in shared care.

Further research

This is the first time that access to preventive health care has been examined from the perspective of PWLE in Australia using Levesque, Harris and Russell’s access framework. Further research is needed to inform innovations that can address the challenges and action the recommendations identified in this study. For example, building the health literacy of PWLE and their supports, improving the capacity of health providers to provide effective preventive health services for PWLE and improving shared care between GPs and the MHS. Other innovations to support access need to be developed. This could include digital or web-based tools.

Limitations

This group of PWLE was supported by a MHS that actively connected them with a GP and a nearby medical practice was receptive to this access. Consequently, all the PWLE and carers in our study had a positive story to tell. This is not the case for all PWLE and carers. The results might not be generalisable to PWLE who do not have such supports. The study was conducted in one area of Sydney. A more geographically diverse sample might have generated different information.

Data availability

Participants did not provide consent for the data to be made publicly available. The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. PB is an employee of Sydney Local Health District, whose MHS assisted with recruitment and data collection.

Declaration of funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Disability Innovation Institute at UNSW Sydney.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants and the stakeholders who reviewed the results and their implications.

References

Bartlem K, Fehily C, Wynne O, Gibson L, Lodge S, Clinton-McHarg T, Dray J, Bowman J, Wolfenden L, Wiggers J (2020) Initiatives to improve physical health for people in community-based mental health programs. The Sax Institute, Sydney. doi:10.57022/conj2912

Brophy L, Minshall C, Fossey E, Whittles N, Jacques M (2022) The Future Horizon: Good Practice in Recovery-Oriented Psychosocial Disability Support. Stage Two Report. La Trobe, report. doi:10.26181/17131973.v1

Cabassa LJ, Camacho D, Vélez-Grau CM, Stefancic A (2017) Peer-based health interventions for people with serious mental illness: a systematic literature review. Journal of Psychiatric Research 84, 80-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Calder RV, Dunbar JA, de Courten MP (2022) The Being Equally Well national policy roadmap: providing better physical health care and supporting longer lives for people living with serious mental illness. Medical Journal of Australia 217, S3-S6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Curtis J, Watkins A, Rosenbaum S, Teasdale S, Kalucy M, Samaras K, Ward PB (2016) Evaluating an individualized lifestyle and life skills intervention to prevent antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 10, 267-276.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Devine A, Dickinson H, Rangi M, Huska M, Disney G, Yang Y, Barney J, Kavanagh A, Bonyhady B, Deane K, McAllister A (2022) ‘Nearly gave up on it to be honest’: utilisation of individualised budgets by people with psychosocial disability within Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Social Policy & Administration 56, 1056-1073.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ewart SB, Bocking J, Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Stanton R (2016) Mental health consumer experiences and strategies when seeking physical health care: a focus group study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 3, 233339361663167.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, Allan S, Constanza C, Carney R, Carvalho AF, Chatterton ML, Correll CU, Curtis J, Gaughran F, Heald A, Hoare E, Jackson SE, Kisely S, Lovell K, Maj M, McGorry PD, Mihalopoulos C, Myles H, O’Donoghue B, Pillinger T, Sarris J, Schuch FB, Shiers D, Smith L, Solmi M, Suetani S, Taylor J, Teasdale SB, Thornicroft G, Torous J, Usherwood T, Vancampfort D, Veronese N, Ward PB, Yung AR, Killackey E, Stubbs B (2019) The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 6(8), 675-712.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Happell B, Wilson K, Platania-Phung C, Stanton R (2017) Filling the gaps and finding our way: family carers navigating the healthcare system to access physical health services for the people they care for. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26, 1917-1926.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Bocking J, Ewart SB, Scholz B, Stanton R (2019) Consumers at the centre: interprofessional solutions for meeting mental health consumers’ physical health needs. Journal of Interprofessional Care 33, 226-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris E, Harris MF (2023) An exploration of the inverse care law and market forces in Australian primary health care. Australian Journal of Primary Health 29, 137-141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris M, Lloyd J (2012) The role of Australian primary health care in the prevention of chronic disease. Report prepared for ANPHA. CPHCE, Sydney. Available at https://adma.org.au/download/the-role-of-australian-primary-health-care-in-prevention-of-chronic-disease/

Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G (2013) Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health 12, 18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T, Aquila R, Charlson F, Cuijpers P, Druss B, Dudek K, Freeman M, Fujii C, Gaebel W, Hegerl U, Levav I, Munk Laursen T, Ma H, Maj M, Elena Medina-Mora M, Nordentoft M, Prabhakaran D, Pratt K, Prince M, Rangaswamy T, Shiers D, Susser E, Thornicroft G, Wahlbeck K, Fekadu Wassie A, Whiteford H, Saxena S (2017) Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry 16, 30-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Melamed OC, Fernando I, Soklaridis S, Hahn MK, LeMessurier KW, Taylor VH (2019) Understanding engagement with a physical health service: a qualitative study of patients with severe mental illness. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 64, 872-880.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Parker SM, Paine K, Spooner C, Harris M (2023) Barriers and facilitators to the participation and engagement of primary care in shared-care arrangements with community mental health services for preventive care of people with serious mental illness: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 23, 977.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Primary Mental Health Care Services for People With Severe Mental Illness (2019) Australian Government Department of Health, PHN Primary Mental Health Care Flexible Funding Pool Programme Guidance, Canberra. Available at https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.health.gov.au%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fdocuments%2F2021%2F04%2Fprimary-health-networks-phn-primary-mental-health-care-guidance-services-for-people-with-severe-mental-illness-primary-health-networks-phn-primary-mental-health-care-guidance-primary-mental-health-care-services-for-people.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK. [Accessed 4 July 2023]

RACGP (2023) Shared Care Model between GP and non-GP specialists for complex chronic conditions. Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/advocacy/position-statements/view-all-position-statements/clinical-and-practice-management/shared-care-model-between-gp-and-non-gp-specialist. [Accessed 13 October 2023]

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2018) ‘Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice (The Red Book),’ 9th edn. (RACGP: Melbourne). Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Clinical%20Resources/Guidelines/Red%20Book/Guidelines-for-preventive-activities-in-general-practice.pdf

Stumbo SP, Yarborough BJH, Yarborough MT, Green CA (2018) Perspectives on providing and receiving preventive health care from primary care providers and their patients with mental illnesses. American Journal of Health Promotion : AJHP 32, 1730-1739.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thomas H, Best M, Mitchell G (2020) Whole-person care in general practice: ‘Factors affecting the provision of whole-person care’. Australian Journal of General Practice 49, 215-220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thornicroft G, Sunkel C, Aliev AA, Baker S, Brohan E, el Chammay R, Davies K, Demissie M, Duncan J, Fekadu W, Gronholm PC, Guerrero Z, Gurung D, Habtamu K, Hanlon C, Heim E, Henderson C, Hijazi Z, Hoffman C, Hosny N, Huang F-X, Kline S, Kohrt BA, Lempp H, Li J, London E, Ma N, Mak WWS, Makhmud A, Maulik PK, Milenova M, Cano GM, Ouali U, Parry S, Rangaswamy T, Rüsch N, Sabri T, Sartorius N, Schulze M, Stuart H, Salisbury TT, Juan NVS, Votruba N, Winkler P (2022) The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. The Lancet 400(10361), 1438-1480.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Vereeken S, Peckham E, Gilbody S (2023) Can we better understand severe mental illness through the lens of Syndemics? Frontiers in Psychiatry 13, 1092964.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whiteford H, Buckingham B, Harris M, Diminic S, Stockings E, Degenhardt L (2017) Estimating the number of adults with severe and persistent mental illness who have complex, multi-agency needs. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 51, 799-809.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |