Capacity building for mental health services: methodology and lessons learned from the Partners in Recovery initiative

Tania Shelby-James A * , Megan Rattray

A * , Megan Rattray  A , Garry Raymond A and Richard Reed A

A , Garry Raymond A and Richard Reed A

A

Abstract

The Partners in Recovery (PIR) program was implemented by the Australian Government Department of Health. Its overriding aim was to improve the coordination of services for people with severe and persistent mental illness, and who have complex needs that are not being met. The PIR capacity-building project (CBP) was funded to provide capacity building activities to the nationwide network of consortia that were set up in 2013 to deliver PIR over a 3-year period. The purpose of this paper is to describe the design and findings from an evaluation of the PIR CBP.

The evaluation involved collecting feedback from consenting PIR staff via an online survey and follow-up semi-structured interviews. CBP activities included: state and national meetings; a web portal; teleconferences; webinars; a support facilitator mentor program; and tailored support from the CBP team.

The CBP made a positive contribution to the implementation and delivery of PIR. Staff highly valued activities that employed face-to-face interaction or provided informative knowledge exchange, and were appreciative of CBP staff being responsive and adaptable to their needs.

From this evaluation, we recommend the following: identify relevant functions (e.g. prioritise networking), select the right mode of delivery (e.g. establish an online presence) and abide by key principles (e.g. be responsive to staff needs). This information is informing the mental health workforce capacity building activities that our team is currently undertaking.

Keywords: capacity building, evaluation, implementation, knowledge exchange, mental health, mixed-methods, Partners in Recovery, workforce.

Introduction

Mental illness accounts for 13% of the total disease burden in Australia, with $431 AUD per person (i.e. $11 billion) spent on mental health-related services in 2019–2020 (AIHW 2022). Approximately 500 000 Australian adults (3.3.%) experience severe mental illness, of which 59 000 (12%) will have persistent symptoms that require multi-agency support (Whiteford et al. 2016). Individuals with severe and persistent mental illness have diverse experience and circumstances (Whiteford et al. 2014), and commonly need to navigate a complex health system involving multiple health sectors and providers. For these reasons, many do not receive the treatment they need (National Mental Health Commission 2014). Considering these findings, the Australian Government pledged to prioritise resolving the fragmentation of psychosocial service delivery and address the continuing issue of care coordination.

In 2013, the Australian Government Department of Health developed the Partners in Recovery (PIR) initiative; a nationwide program designed to better support people living with severe and persistent mental illness (Department of Health and Aged Care 2016). The overarching aim of the PIR initiative was to improve coordination of services for people with severe and persistent mental illness with complex needs, and their carers and families. It was intended that the PIR initiative would support 2000 people by June 2016. Given that this was a new way of providing mental health care, Flinders University was funded to deliver a capacity-building program (CBP) to support and develop the knowledge, skills and expertise of community-based mental health providers delivering PIR.

Capacity-building initiatives, which aim to develop and enhance the knowledge and abilities of health providers, have been acknowledged as necessary for success in advancing new public health initiatives (DeCorby-Watson et al. 2018). Such initiatives can be targeted at individuals and/or organisations, and take a variety of forms, including guidance materials in the form of knowledge products and/or skills-based courses providing technical assistance, virtual and/or in-person training sessions/consultations, and coaching/mentoring (Caron and Tutko 2009; Gagliardi et al. 2014). Despite the recognised importance of such initiatives, there remains limited evidence to inform effective approaches for capacity building in mental health (Liu et al. 2016), particularly in the Australian context.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the design and findings from an evaluation of the PIR CBP. This information will inform future capacity-building activities within the mental health service system.

Context

The PIR CBP supported the nationwide network of PIR organisations funded to implement and deliver PIR. PIR organisations consisted of a consortium of organisations within a given region who had a shared mission to support people with severe and persistent mental health conditions. Within the PIR organisations, a lead organisation acted as the backbone organisation, and coordinated all activities and services. This included facilitating collaboration between relevant sectors, services and supports.

The PIR program operated within a complex policy environment characterised by ongoing systems-level change (for example, the introduction of Primary Health Networks and the National Disability Insurance Scheme) affecting both PIR staff and participants. To address this complexity, as well as the complex needs of the PIR participant group that were not being adequately met by existing service models, the CBP activities were purpose designed to support the unique needs of PIR staff and organisations, and were responsive to changing circumstances within the program. The CBP was intended to reach approximately 1300 staff across Australia. The CBP was one of the few constant and consistent supportive presences within the rapidly evolving environment.

The practice innovation

The initial funding cycle for the PIR CBP was aligned with the same cycle for the PIR initiative, starting in the second quarter of 2013 and concluding in the second quarter of 2016. Below is a summary of the design of the CBP and how it was evaluated.

Design of the CBP

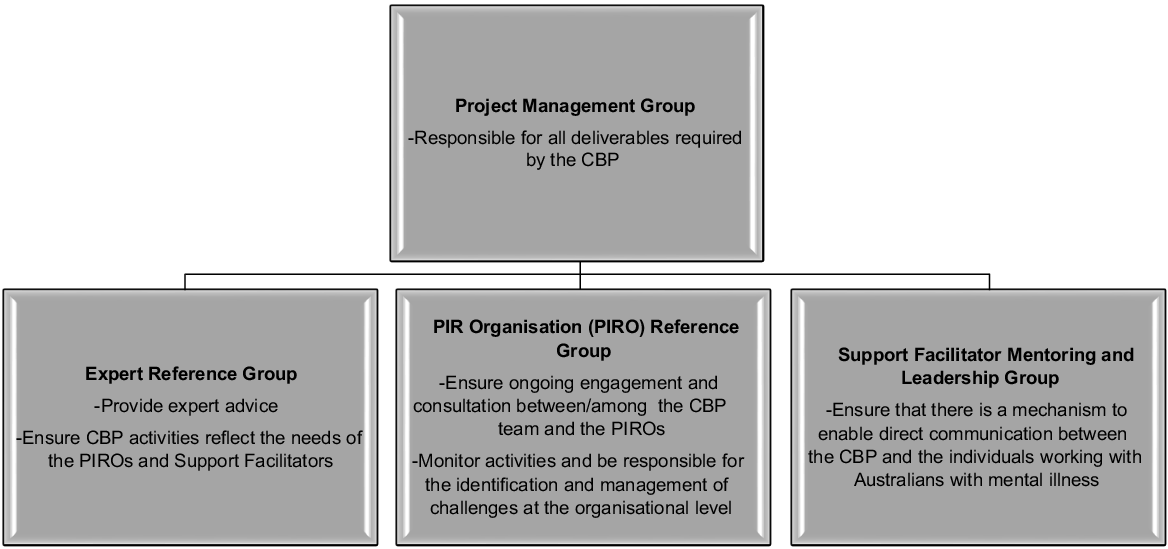

The CBP team adapted the diffusion of innovations framework Rogers (1995) to assist PIR organisations with the implementation and conduct of the PIR initiative. The CBP framework took a strengths-based approach to PIR by focusing on what was working well and how gaps in knowledge and skills could be proactively addressed. Further, given formal structures and roles are important for fostering collaboration within health promotion initiatives (Horn et al. 2014), a comprehensive governance structure to oversee the ongoing development and effectiveness of the CBP was established (Fig. 1). This was comprised of three committees that ensured that external stakeholders, service providers, and staff from all levels of PIR were engaged and consulted, thereby using existing skills and increasing knowledge and ownership of the project across all stakeholder groups.

The CBP undertook several activities that aimed to enhance the skills and knowledge of staff involved in PIR (Table 1). These activities were underpinned by four key capacity-building principles (Brunero and Lamont 2010): (1) respecting and valuing pre-existing skills; (2) developing trust; (3) being responsive to local needs and tailoring strategies to suit; and (4) developing well-integrated strategies.

| Activity type | Function(s) | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web portal | Information dissemination, training and networking | Launched in June 2013 and continually revised based on feedback from end users, the web portal was a central point of access for the tools and resources developed to implement the PIR. The portal included: online (1) training modules, (2) forums, (3) resources (including a directory of organisations and staff contact details, PIR guidelines and templates, event information, webinar recordings) and (4) featured articles. The forums were intended to provide a ‘share-point’ for PIR members to blog about news and experiences, share best practice approaches to PIR, and ask questions of the wider PIR network. The training modules, resources and featured article were intended to equip PIR staff with basic knowledge in key areas of service coordination. | |

| State and national meetings | Networking and information dissemination | A national meeting was held once a year to allow PIR organisations to build networks and collectively address key strategic issues and challenges of national relevance. State meetings were held twice a year for each state/territory to allow PIR staff to focus on matters of local importance and reinforce state-based relationships. These meetings followed a traditional ‘conference’ format including keynote presentations from guest speakers and workshops. | |

| Support Facilitator (SF) mentor program | Mentoring | The SF mentor program was designed to ensure each organisation had a mentor registered with the program who could provide peer mentoring to other staff within PIR in their region. Biannual meetings for all mentors and relevant training and opportunities for networking and discussion were provided. | |

| Teleconferencing | Networking, mentoring and information dissemination | Fortnightly (for all staff) and monthly (for all SFs) teleconferences were held to allow individuals to share experiences, establish new contacts and ask questions of each other and the CBP. Often a speaker was invited to present on a specific topic at the beginning of the call. Of note, these were used as an interim measure while the online networking forums were being developed. | |

| Webinars | Information dissemination and networking | Webinars provided an opportunity for PIR staff from all over Australia to meet in a ‘virtual’ environment and discuss themes of key importance to the PIR program by experts in the area. All webinars were available for viewing on the web portal after the event and provided another resource for staff within PIR. | |

| Team support | Information dissemination and training | The CBP team at Flinders University provided direct support to PIR staff. This was provided as needed through a dedicated support line (an 1800 number) and one-on-one tailored support (over the phone or email). Further, weekly email updates were circulated to keep PIR staff abreast of upcoming events, trends and outcomes within the national PIR community. |

Evaluation of the CBP

A prospective mixed-methods design was utilised to evaluate the CBP. Quantitative data included a survey (June and July 2015), whereas qualitative data included semi-structured interviews (July and August 2015). The survey was sent to staff of all organisations funded to deliver PIR.

The survey included two dichotomous (yes/no) questions designed to determine the extent to which PIR staff were aware of each of the CBP activities provided and their level of engagement with each; and 14 4-point Likert-scale questions to ascertain the ‘helpfulness’ of each CPB activity (1 = very helpful; 2 = helpful; 3 = unhelpful; 4 = very unhelpful). The survey was circulated in online and paper-based formats, and only open to people with more than 1 month of experience working in PIR. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise responses.

Survey respondents were offered the option of participating in a follow-up semi-structured interview, to provide greater insight into the strengths and limitations of the CBP. A CBP staff member who had not previously had significant interaction with PIR staff conducted all interviews one-to-one over the phone. Recruitment continued until data saturation (i.e. no new information was identified) was reached. Interviews were audio-taped and later transcribed verbatim for analysis. Qualitative data were analysed using content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs 2008). This involved two CBP staff members reading and rereading the transcribed interviews and identifying codes from the data, which were grouped into subcategories, then categories.

Outcomes of the CBP

Of the 1303 registered users, a total of 104 PIR staff completed the online survey. Most staff indicated that they had between 1 and 2 years of experience of working in PIR and occupied the following roles: PIR Program Manager (n = 18), Team Leader (n = 9), Consumer Representative (n = 5), PIR Contract Manager (n = 4), Policy Staff (n = 4), Project Officer/Contractor (n = 4) and Coordinator (n = 4). Of these respondents, 23 completed a follow-up interview. Their roles included: Support Facilitator (n = 8), PIR Manager (n = 6), PIR Project Officer (n = 3), PIR Team Leader (n = 2) and Consumer Representative (n = 1).

Fig. 2 shows the amount of self-reported awareness and uptake of the different capacity-building activities and resources offered by the CBP. The most widely accessed and used activities were the weekly e-mail updates, the web portal forums and the webinars. The high level of participation in the webinars is noted here, particularly as the webinars were a feature that was not originally offered by the CBP, but later developed in October 2014. The least used activity was the 1800 number.

Among survey respondents who participated in various capacity-building activities, the annual national meeting was rated most highly in terms of helpfulness. Other activities that were rated most highly were direct one-to-one contacts with CBP staff either via telephone or e-mail. The activity that received the highest number of negative ratings of either ‘unhelpful’ or ‘very unhelpful’ was the fortnightly teleconferences open to all. However, the monthly teleconferences for Support Facilitators were maintained, and these received more positive ratings than the fortnightly teleconferences.

Table 2 summarises interview respondents’ general perceptions about the CBP, whereas Table 3 describes their feedback on individual CBP activities.

| 1. Viewing the capacity-building team as performing well in a very difficult area | ||

| The CBP positively impacted on staff’s ability to address the challenges implementing the PIR program. For example, without a capacity-building component to PIR, the following were seen as real risks: inconsistency and lack of direction; isolation of staff and ideas; staff feeling lost; lack of overall information and information exchange; and less efficiency, sharing and support. | ||

| ‘I think …the capacity building project … has achieved a significant amount in a very, very tough space. Trying to find some … middle ground around meeting the needs, the expectations and the delivery of certain types of information across the multiple stakeholders, I think was always going to be a very tough gig, and [the CBP have] ultimately met the middle ground where the majority of the needs are being met by the availability of the information in the format and in the approaches that are being undertaken.’ | ||

| 2. Highly valuing the opportunity to network and exchange information | ||

| It was clear that a highly valued aspect of the CBP was the various opportunities offered for networking and information exchange. Importantly, people recognised that the CBP had endeavoured to communicate information in multiple formats, which appealed to a diverse range of audiences and made knowledge more accessible. | ||

| ‘Helping people to be able to liaise and network… [has] been the real heart of the program’s success.. So without that, I don’t think the program would be where it is, and it would be very siloed if it was to even get there and it would become very fragmented in its delivery and its approach.’ | ||

| 3. Juggling competing interests to work and access available activities | ||

| Some interviewees indicated that they did not have sufficient time available to access the activities due to competing work demands (e.g. making a post on the forums). For some, they acknowledged that they missed out, having accessed activities in the early stages when they had more time, while others accessed little from the start. Interviewees placed responsibility for not accessing CBP activities onto the users or considered there was a need to share responsibility. | ||

| ‘You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make them drink; the capacity building I see has pretty much done that. It’s put every type of mechanism there. It’s given everybody the opportunities to actually be in the one place at the same time, even using technology to do so. Now it’s up to the people to actually pick that up and to do something with it.’ | ||

| Web portal: seeing substantial value in the resources offered | ||

| The portal was seen as a rich source for information sharing and was considered a good place to make comparisons with what others had been doing. However, several people did comment on difficulties navigating the portal. These difficulties were due to website design factors and/or information being out of date or missing. Where difficulties were due to the former, interviewees acknowledged that there had been a subsequent improvement in the design of the web portal. Specifically, the online training modules were variously described as ‘flexible’, ‘useful’, ‘excellent’ and ‘invaluable’. Some senior staff used the modules to grasp what level of knowledge they were aiming to impart among new staff, while others used the information to help confirm what they already knew. The featured articles were seen as a useful and quick way to see what was going on, and people liked sharing them with a wider audience as they were seen to be motivating. Lastly, the forums were widely visited by participants to learn what was happening. However, some participants stated they were passive users, indicating they would be more likely to post if they had the choice to be anonymous. | ||

| ‘It’s been critical for me. I know some others may not access the capacity-building information as much; we all do it to varying degrees. At a personal level and a program delivery level, that’s been my first source of updated information. That’s been my first source of generating ideas and questions.’ | ||

| State and national meetings: highly valuing the opportunity to network and share ideas | ||

| These meetings were generally highly valued by interviewees, and considered well planned and presented. The greatest perceived benefit was the opportunity to network, although they were also found to be motivating and inspiring. The subsequent recordings on the portal were also particularly useful, as they assisted revision and sharing of the content with others who did not attend the workshops. Concerns with the workshops included: limited attendance, informal time to network and few presentations from ‘lived experience’ individuals or those with practical experience in the field. These limits changed over time to allow additional representation, but it remained an area of concern. | ||

| ‘I enjoy the networking aspect as it allows me to see and speak to new people and others I’ve known since starting in the industry.’ | ||

| Teleconferencing: lacking ease of participation and purpose | ||

| The teleconferences appeared to be the least valued activity. Many participants listed this activity in response to being asked what hadn’t worked in relation to the CBP. Several reasons were listed for this: lack of purpose, difficulty participating given the absence of face-to-face contact and its structure (e.g. one person talking for an extended period of time) and no follow-up (e.g. the distribution of minutes to refer back to what was covered). However, one participant did acknowledge that the teleconferences likely ‘helped the webinars evolve’, while another stated they shared the knowledge gained through this activity with others in their workplace. | ||

| ‘Initially they didn’t have a lot of structure, and there didn’t seem to be a lot of purpose. It was like, you know, facilitated to say, so what does anybody want to bring up? Of course, everybody sits there completely silent…I haven’t been a great participator of them in the last little while, partly due to time and partly to due expense, and partly due to: is this the best use of my time?’ | ||

| Webinars: valuing the ability to chat and access training | ||

| Webinars were valued due to the ability to chat on the side and therefore not have ideas lost. There was good follow-up information available due to being able to access the recording of the webinar and the support materials. Webinar recordings were also seen to be a useful training tool for staff. | ||

| ‘The webinars have been really good to be able to very quickly ask questions, kick ideas around, get that sort of live feedback which you don’t kind of get so much on the forum. You can to and fro a question and get to some of the context or richness.’ | ||

| Support Facilitator mentor program: recognising the value but requiring further work | ||

| The Support Facilitator (SF) mentor program received mixed feedback. Staff valued the ‘good work’ SFs do to support others; however, it was suggested that their reach and engagement was not as good as it could have been. Indeed, some staff commented on the workload SFs had as being a contributing factor, emphasising the difficulty of balancing their consumer engagement commitments with their mentoring responsibilities and participation in CBP activities. Further, the ‘big turnover’ of SFs and their lack of supervision/support were suggested as contributing factors. | ||

| ‘We haven’t had as much uptake in the mentor and leadership group in terms of support facilitators from around the nation actually accessing the mentoring, which was kind of a surprise. So I wouldn’t say it didn’t work; it was just kind of mysterious why more people didn’t access it.’ | ||

| Team support: appreciating the responsiveness and accessibility of the team | ||

| The responsiveness and accessibility of the CBP team received overwhelming positive feedback. This appeared to be attributed to how responsive the team was to staffs’ queries and how accommodating they were to their needs. Further, the weekly updates were generally highly valued as a form of ‘concise’ and easily accessible information sharing. However, some participants acknowledged that they did not read them. | ||

| ‘… I have phoned people at various times and gone, ‘how do I do X’, and got answers. It’s really good. It’s like, you know, you go fishing, you don’t plan to fall overboard, but it’s nice to know you’ve got your lifejacket on.’ | ||

What can be learnt

The CBP, which aimed to provide support and develop knowledge for new and existing staff, was important for the implementation of the PIR program. The array of activities offered, including online training modules and resources, face-to-face training and workshops, and regular teleconferences, were highly valued by staff. Activities that employed face-to-face interaction or provided interactive knowledge exchange were preferred over the static online resources, and staff were appreciative of the CBP team being responsive and adaptable to their needs. The key factors that lead to the success of the CBP are outlined below.

Identifying the most relevant functions

A cornerstone of the PIR CBP was the development of a robust Community of Practice that facilitated networking and knowledge exchange. Indeed, there is good evidence suggesting that there is substantial need for interorganisational networking when implementing a complex and innovative program (Greenhalgh et al. 2004), and that reflecting on innovations within a program can provide new directions for program staff (Plesk and Wilson 2001). Within PIR, networking activities provided a mechanism for looking across organisations, and generalising the challenges and successes of PIR. Networking activities included the state and national meetings, complemented by teleconferences, webinars and online discussion forums. However, some networking activities were more successful than others. For example, the webinars and state and national meetings were highly valued by staff, whereas the teleconferences received the most negative feedback of all activities offered. The absence of face-to-face interaction likely contributed to this finding. Since the evaluation of PIR, the use of online video meetings through Skype and Microsoft Teams have increased significantly and have replaced teleconferences. Participants within the successor CBP have informally reported that online Community of Practices through Microsoft Teams are highly effective, and have created an environment where staff feel comfortable and motivated to actively engage to discuss key issues. However, as shown by other work, staff continue to value face-to-face networking opportunities, especially given the online fatigue caused by the past 2 years of COVID-19 lockdowns (Bonanomi et al. 2021). Given face-to-face peer networks have been shown to enhance and sustain practice change by facilitating person connections (Donald et al. 2013), future CBPs should include a mix of face-to-face and online networking options. Using a hybrid model of face-to-face support supplemented by online Communities of Practice results in economic savings, as face-to-face activities are costly, both in terms of time and money, whereas online platforms are generally free to use.

Selecting the right mode of delivery

Establishing an online presence early in the implementation of PIR was critical. The web portal developed served the dual purpose of facilitating networking and information sharing, as well as providing a means for disseminating critical information about the PIR initiative, such as training and directives from the funding body. The breadth of the resources available via the portal grew exponentially as PIR organisations shared knowledge with one another, to the point where it served as a ‘one stop shop’ for new and existing staff to access important and up to date information about PIR. In particular, the series of online training modules and the featured weekly articles were highly valued as training, learning and motivating resources by PIR staff. Indeed, previous work has shown this approach is the preferred learning method for health professionals, as it allows for effective and efficient delivery of education materials, given it is convenient and flexible (Horn et al. 2014). The online platform architecture developed for PIR continues to be used as the basis for the delivery of the successor program (the Commonwealth Psychosocial Support Program).

Abiding by key principles

Adapting aspects of the CBP based on staff feedback, and responding to their queries in a timely and informative manner was essential to the success of the program. For example, the web portal continued to be modified based on the feedback of those using the site, and this was appreciated and acknowledged by staff, as evidenced in the interviews. Further, given the PIR program operated within a complex policy environment characterised by ongoing change, it was important that CBP staff were responsive and adaptable to the needs of PIR staff, and provided information and direction without delay. This approach is supported by evidence demonstrating that capacity-building activities are most effective when they are tailored to respond to the organisational context in which the initiative is delivered, and when targeted to the needs of the different staff groups within these organisations (Brunero and Lamont 2010). These findings indicate that timely and effective communication with staff is a cornerstone of effective change management, and should therefore be prioritised when delivering CBPs in complex and changing environments.

Limitations of the evaluation

We recognise several limitations in the present study. First, the evaluation was completed in 2015; however, the findings are still relevant in the current context, and have informed aspects of the CBP model being utilised in PIR successor programs (the National Psychosocial Support programs (2016–2021) and then the Commonwealth Psychosocial Support Program (2022–ongoing)). Additionally, the low response rate (8%) limits the generalisability of our findings. The timing of the evaluation may have contributed to the response rate to some extent, as it occurred during the transition from Medicare Locals to Primary Health Networks. This transition resulted in contractual changes, resulting in higher staff turnover than normal throughout the course of the evaluation. There was also a substantial increase in workload for continuing PIR staff during this period. Despite this, the findings from the survey were supported through subsequent qualitative interviews whereby data saturation was reached.

Conclusion

CBPs should not adopt a one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, they require a range of activities and resources that can be tailored according to local needs and the context. The model presented here provides a guide for other capacity-building activities in complex health initiatives. The learnings from the CBP continue to be used today by the research team to support Commonwealth funded community psychosocial support programs within Australia, and consist of networking through face-to-face and online opportunities, an online portal to share resources and deliver online training, and timely communication with staff.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; or in the writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the Australian Government Department of Health (now referred to as the Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government). The funder had no role in preparation of the data or manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Partner in Recovery staff and consumers who were part of this initiative.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2022) Mental health services in Australia: Mental health: prevalence and impact. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health [Accessed 8 August 2022]

Bonanomi A, Facchin F, Barello S, Villani D (2021) Prevalence and health correlates of Onine Fatigue: a cross-sectional study on the Italian academic community during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 16, e0255181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brunero S, Lamont S (2010) Mental health liaison nursing, taking a capacity building approach. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 46, 286-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Caron RM, Tutko H (2009) Applied topics in the essentials of public health: a skills-based course in a public health certificate program developed to enhance the competency of working health professionals. Education for Health 22, 244.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

DeCorby-Watson K, Mensah G, Bergeron K, Abdi S, Rempel B, Manson H (2018) Effectiveness of capacity building interventions relevant to public health practice: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 18, 684.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Department of Health and Aged Care (2016) Psychosocial support for people with severe mental illness. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/commonwealth-psychosocial-support-programs-for-people-with-severe-mental-illness?utm_source=health.gov.au&utm_medium=callout-auto-custom&utm_campaign=digital_transformation [Accessed 10 August 2022]

Donald M, Dower J, Bush R (2013) Evaluation of a suicide prevention training program for mental health services staff. Community Mental Health Journal 49, 86-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62, 107-115.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Perrier L, Bell M, Straus S (2014) Exploring mentorship as a strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research and practice: a scoping systematic review. Implementation Science 9, 122.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O (2004) Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly 82, 581-629.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Horn MA, Rauscher AB, Ardiles PA, Griffin SL (2014) Mental health promotion in the health care setting: collaboration and engagement in the development of a mental health promotion capacity-building initiative. Health Promotion Practice 15, 118-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Liu G, Jack H, Piette A, Mangezi W, Machando D, Rwafa C, Goldenberg M, Abas M (2016) Mental health training for health workers in Africa: a systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry 3, 65-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Plesk PE, Wilson T (2001) Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organizations. British Medical Journal 323, 625-628.

| Google Scholar |

Whiteford H, McKeon G, Harris M, Diminic S, Siskind D, Scheurer R (2014) System-level intersectoral linkages between the mental health and non-clinical support sectors: a qualitative systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 48(10), 895-906.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Whiteford H, Buckingham B, Harris M, Diminic S, Stockings E, Degenhardt L (2016) Estimating the number of adults with severe and persistent mental illness who have complex, multi-agency needs. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 51, 799-809.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |