GPS telemetry facilitates the identification of forage plant species for endangered Carnaby’s cockatoos (Zanda latirostris) at inland breeding sites and post-breeding dispersal locations in Western Australia

Zoë M. Kissane A * , Karen J. Riley A , Kristin S. Warren A B and Jill M. Shephard

A * , Karen J. Riley A , Kristin S. Warren A B and Jill M. Shephard  A

A

A

B

Abstract

Carnaby’s cockatoos (Zanda latirostris) are an endangered species that has experienced major loss of habitat over the past century. Proponents seeking land clearing approval that may impact Carnaby’s cockatoos need to provide detailed habitat assessment. However, the current forage species list is outdated and generally restricted to the Swan Coastal Plain rather than the Carnaby’s full distribution range. This study provides an updated forage list, including the Swan Coastal Plain and much of the Carnaby’s breeding and non-breeding areas outside this region. Carnaby’s cockatoos were captured and satellite tagged, at five breeding sites in the wheatbelt and Great Southern areas in Western Australia (between 2017 and 2022). Spatial data collected from the tags facilitated the identification of forage plants used by Carnaby’s cockatoos. A total of 44 ‘new’ native plant species were identified as Carnaby’s cockatoo forage species, including five genera that have not previously been recorded. The updated forage list will inform proponents and regulators on the potential use of habitat patches by Carnaby’s cockatoos, aiding the referral process and enabling the protection and conservation of important and diminishing habitat resources.

Keywords: biodiversity offset, Carnaby’s cockatoo, conservation management, endangered species, forage species, foraging ecology, GPS telemetry, movement ecology, Zanda latirostris.

Introduction

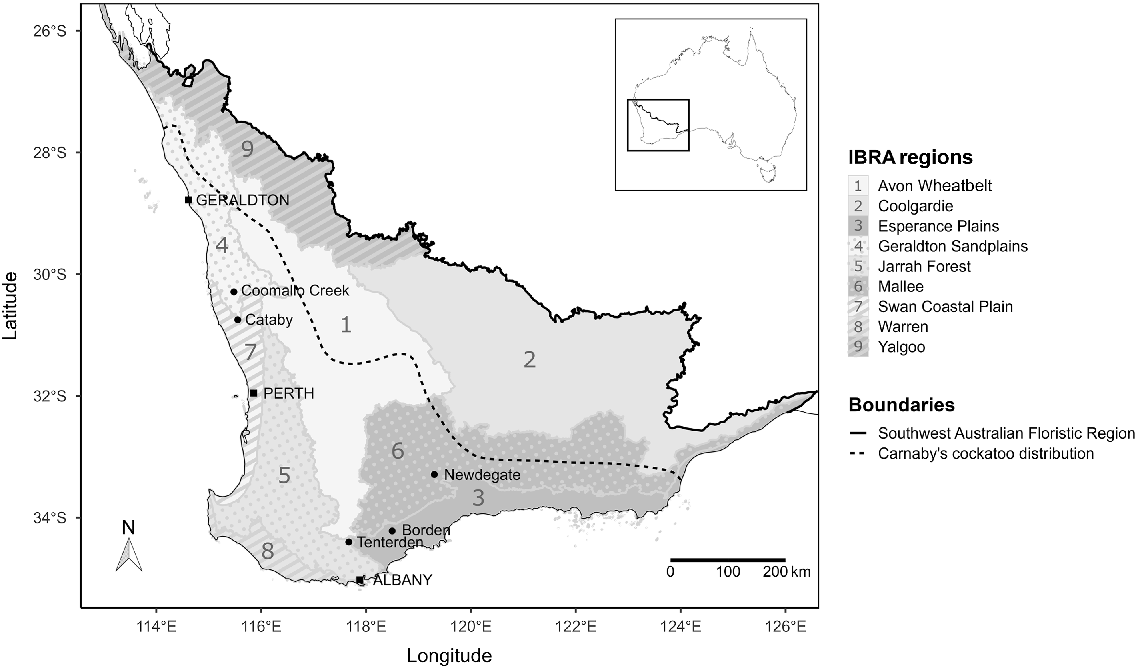

Habitat loss and fragmentation are major threats to wildlife globally (Sullivan et al. 2021; de Souza Leite et al. 2022). This is particularly so for Carnaby’s cockatoos (Zanda latirostris), an iconic Western Australian species that has experienced a decline in population and a 30% range contraction over the past century (Saunders 1990), with a recently estimated reduction of 2% annually between 2010 and 2022 (Pryor et al. 2023). Carnaby’s cockatoos are listed as Endangered under both state and Australian federal law, and internationally by the IUCN (Department of Environment and Conservation 2012). The Carnaby’s cockatoo distribution is within the Southwest Australian Floristic Region (SWAFR) (Fig. 1), known for its species richness and endemism.

Carnaby’s cockatoo distribution range and the Southwest Australian Floristic Region including Interim Biogeographical Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) regions. Breeding grounds related to this study are named on the map with a black dot. Major cities are marked with a black square and written in capital letters. Non-breeding dispersal locations where some of the forage species from this study were identified are in Table 1.

Proponents seeking approval to clear land impacting Carnaby’s cockatoo foraging or breeding habitat must provide a detailed habitat assessment, showing they have surveyed its suitability for use by black cockatoos. According to the Australian ‘Federal Referral Guidelines for Black Cockatoos’ (DAWE 2022) (hereafter the Referral Guidelines), actions resulting in loss of foraging habitat may require referral to the Minister for the Environment and Water for approval. To determine whether a particular patch of habitat is suitable for use by black cockatoos it is assessed according to the ‘Scoring Tool Template’ found within the Referral Guidelines, which considers the condition, context and stocking rate of habitat patches. This template also states that a site will start with the maximum ‘score’ if it contains known foraging species. The Referral Guidelines state that habitat assessments must be sufficient to complete the ‘Scoring Tool’ and must consider key attributes including foraging potential and habitat patch connectivity, with a view to meeting the standard of ‘no net loss’ of habitat over time (Maron et al. 2010, 2021; DAWE 2022).

When conducting habitat assessments for black cockatoos, environmental consultants often refer to the list in ‘Plants Used by Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo’ (Groom 2011) and the ‘Scoring system for the assessment of foraging value of vegetation for Black-Cockatoos’ (Bamford 2020). The scoring tool described by Bamford (2020) states that if known food plants exist in a habitat patch is to be cleared, then the patch will score higher accounting for its foraging value. It is the list from Groom (2011) that most consultants refer to during this assessment process for guidance regarding known forage species. The list is comprehensive (Groom 2011), but mainly contains species found on the Swan Coastal Plain; Interim Biogeographical Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) region Swan Coastal Plain (SWA) (DCCEEW 2023); an area utilised by Carnaby’s cockatoos during the non-breeding season. It does not document many Carnaby’s cockatoos forage species found in other parts of their distribution, particularly from the northern, southern and inland areas where most breeding occurs (Saunders 1974).

To aid in the conservation and retention of Carnaby’s cockatoo’s habitat, it is important to assess foraging habitat suitability across their whole distribution, not only within the SWA. To fill this knowledge gap, we used direct observation and GPS telemetry to identify plant species foraged on by Carnaby’s cockatoos outside the SWA region. Globally, the use of GPS telemetry (and movement ecology data) has facilitated greater understanding of the foraging ecology of many species, with tracking devices providing accurate location data that can be used to determine where and on what animals are foraging (Nathan et al. 2008; Joo et al. 2022). This information is particularly important for endangered species as knowledge about their foraging ecology and dietary preferences can facilitate the conservation and protection of patches containing key food resources. Here, we present an updated forage list for Carnaby’s cockatoos compiled during a broader telemetry study into the movement ecology of this species.

Materials and methods

Tag attachment and data acquisition

A total of 46 adult wild breeding Carnaby’s cockatoos were captured and tagged at five breeding sites in the wheatbelt and Great Southern areas in Western Australia (between 2017 and 2022) (Fig. 1; exact breeding ground locations are not given as this species is conservation-sensitive). Birds were fitted with two telemetry tags: (1) a Telonics (TAV 2617) Argos Platform Terminal Transmitter (PTT) satellite tag; and (2) an accelerometer capable solar UvA-BiTS GPS tag (Bouten et al. 2013) to obtain movement data on the birds spatial and temporal use of resources. Argos tags were programmed to turn on at night (20:00–00:00 hours) before a scheduled flock follow identifying night roost locations, and facilitating morning flock follows using an ARGOS AL-1 PTT Locator. Argos position locations were also used to locate the birds to facilitate the download of GPS data using a remote base station. Tags comprised less than 5% of the total body weight (Aldridge and Brigham 1988) and were mounted as per the methods described in Le Souef et al. (2013), Groom et al. (2015) and Yeap et al. (2017). Birds were tracked during the incubation and provisioning period at the breeding ground (1–68 days, Fig. 1), during their post-breeding dispersal phase (4 days), and in range resident areas across their non-breeding range (maximum of 92 days).

Forage species identification

Patches of habitat and forage plants used by Carnaby’s cockatoos were identified in two ways: (1) by observing tagged birds foraging in the field where their location was informed using the Argos tag position; and (2) by analysing the GPS data to identify activity ‘hot spots’ and patches during daytime forage hours using the getRecursionsAtLocations function in the ‘Recurse’ package in R R Core Team 2023 (Bracis et al. 2018). These sites were retrospectively visited to identify and collect forage remains. Where possible, plants were identified in the field, otherwise a specimen or photographs were collected for formal identification.

Results

A total of 44 native plant species, additional to the ones in Groom’s (2011) list, were identified as Carnaby’s cockatoo forage species. Most of the species identified were from the Proteaceae family, and were either in the Banksia (n = 22) or Hakea (n = 10) genus. Genera that were not in Groom’s (2011) list but identified in this study include Adenanthos, Allocasuarina, Daviesia, Mesomelaena, and Xylomelum (Table 1). A total of 410 days were spent in the field collecting data and observations. All observed foraging was of flocks ranging in size from 30 to 800 birds. Forage patches generally comprised multiple plant species and it was common to see different birds in the same flock feeding on different species. Typically, average daily foraging distance travelled for incubating or provisioning Carnaby’s cockatoos was 5.92 ± 4.40 km).

| Genus | Species | Common name | IBRA regions where plant species occurs | Forage location (IBRA code) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia | acuminata | Jam | AVW, COO, ESP, GES, GVD, JAF, MAL, MUR, NUL, SWA, YAL | CocanarupA (ESP) | |

| Acacia | cyclops | Coastal Wattle | COO, ESP, GES, HAM, JAF, SWA, WAR | BordenB (ESP) | |

| Adenanthos | cuneatus | Coastal Jug Flower | AVW, ESP, HAM, JAF, MAL, SWA, WAR | Hopetoun and South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Allocasuarina | humilis | Dwarf Sheok | AVW, ESP, GES, JAF, MAL, SWA, WAR | Wellstead (ESP) | |

| Banksia | arctotidis | Dryandra-leaved Banksia | AVW, ESP, GES JAF, MAL | BordenB (ESP) | |

| Banksia | armata | Prickly Dryandra | AVW, ESP, GES JAF, MAL, SWA, WAR | TenterdenB (JAF) | |

| Banksia | baueri | Woolly Banksia | AVW, ESP, MAL | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Banksia | blechnifolia | Fern-like Banksia | ESP, MAL | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Banksia | burdettii | Burdett’s Banksia | GES, JAF, SWA | CoomalloB (GES) | |

| Banksia | caleyi | Red Lantern | ESP, MAL | BordenB (ESP) | |

| Banksia | candolleana | Propeller Banksia | AVW, GES, SWA | Badgingarra (GES) | |

| Banksia | cirsioides | N/A | AVW, COO, ESP, MAL | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Banksia | dryandroides | Dryandra-leaved Banksia | AVW, GES, JAF, SWA | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Banksia | hewardiana | N/A | AVW, GES, JAF, SWA | CatabyB | |

| Banksia | lemanniana | Lemann’s Banksia | ESP, MAL | Fitzgerald River NP (ESP) | |

| Banksia | media | Southern Plains Banksia | ESP, MAL | BordenB (ESP) | |

| Banksia | nutans var. cernuella | Nodding Banksia | AVW, ESP, JAF, WAR | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Banksia | repens | Creeping Banksia | AVW, ESP, JAF, MAL | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Banksia | sphaerocarpa var. pumilio | Round-fruit Banksia | AVW, GES, JAF, SWA | Mount Adams (GES) | |

| Banksia | sphaerocarpa var. sphaerocarpa | Fox Banksia | AVW, ESP, GES, JAF, MAL, SWA | CoomalloB (GES) | |

| Banksia | tenuis | N/A | AVW, ESP, JAF, MAL | Stirling Range NP (JAF) | |

| Banksia | violacea | Violet Banksia | AVW, ESP, MAL | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Banksia | erythrocephala var. erythrocephala | N/A | COO, ESP, MAL | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Banksia | oreophila | Mountain Banksia | AVW, ESP, JAF | Fitzgerald River NP (ESP) | |

| Banksia | pulchella | Teasel Banksia | ESP, MAL | Hopetoun (ESP) | |

| Banksia | obovata | Wedge-leaved Dryandra | AVW, ESP, JAF, MAL | Hopetoun (ESP) | |

| Daviesia | trigonophylla | N/A | AVW, ESP, JAF | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Grevillea | coccinea | N/A | ESP, MAL | Hopetoun (ESP) | |

| Hakea | lasiocarpha | Long-styled Hakea | ESP, JAF | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Hakea | erecta | N/A | AVW, COO, ESP, GES, MAL, SWA | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Hakea | brownii | Fan-leaf Hakea | AVW, GES, JAF, MAL, SWA | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Hakea | corymbosa | Cauliflower Hakea | AVW, COO, ESP, GES, JAF, MAL, SWA | BordenB and South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Hakea | ferruginea | Rusty Hakea | AVW, ESP, JAF | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Hakea | nitida | Frog Hakea | AVW, ESP, HAM, JAF, MAL, WAR | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Hakea | recurva ssp. recurva | Standback | AVW, CAR, COO, GAS, GES, GVD, MUR, SWA, YAL | Chapman Valley (GES) | |

| Hakea | strumosa | N/A | AVW, ESP, MAL | BordenB (ESP) | |

| Hakea | victoria | Royal Hakea | ESP | Fitzgerald River NP (ESP) | |

| Hakea | denticulata | Stinking Roger | ESP, JAF, MAL | Boxwood Hill (ESP) | |

| Isopogon | trilobus | Barrel Coneflower | AVW, COO, ESP, JAF, MAL | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Isopogon | nutans | Simple-leaved Coneflower | ESP, MAL | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Isopogon | longifolius | N/A | AVW, ESP, JAF, MAL, WAR | South Stirling (ESP) | |

| Isopogon | villosus | N/A | AVW, ESP, MAL | NewdegateB (MAL) | |

| Mesomelaena | tetragona | Semaphore Sedge | AVW, ESP, GES, JAF, SWA, WAR, YAL | CatabyB (SWA) | |

| Xylomelum | angustifolium | Sandplain Woody Pear | AVW, GES, JAF, MAL, SWA | Warradarge (GES) |

IBRA, Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia, the known distribution of each species (Western Australian Herbarium 2024). N/A, not applicable.

Forage locations: AVW, Avon Wheatbelt; COO, Coolgardie; ESP, Esperance Plains; GES, Geraldton Sandplains; GVD, Great Victoria Desert; HAM, Hampton; JAF, Jarrah Forest; MAL, Mallee; MUR, Murchison; NUL, Nullarbor; SWA, Swan Coastal Plain; WAR, Warren; YAL, Yalgoo; NP, National Park.

Discussion and conclusion

Of the SWAFR’s nine IBRA7 regions, Carnaby’s cockatoo’s distribution extends across eight IBRA7: (1) Avon Wheatbelt; (2) Coolgardie; (3) Esperance Sandplains; (4) Geraldton Sandplains; (5) Jarrah Forest; (6) Mallee; (7) Swan Coastal Plain; and (8) Warren (Lambers 2014; Brundrett 2021). The list from Groom (2011) contains plants found in several of these regions but was compiled from research concentrated in coastal urban or peri-urban areas. Our updated list adds species found in all nine of the SWAFR IBRA7 regions and, in addition to the SWA, was compiled from research at inland breeding grounds and along post-breeding dispersal routes. This incorporates a broader extent of the Carnaby’s cockatoo’s distribution and will facilitate improved habitat suitability assessment across the species breeding and non-breeding spatial range.

To adequately assess habitat patches for their value, information regarding the foraging ecology of the animal species using these patches is critical. With the aid of GPS telemetry, we have identified and added 44 new forage species and five new genera to the existing forage species list and increased the spatial coverage of known forage species across more of the Carnaby’s cockatoos distribution range. This information will inform regulators on the potential use of habitat patches by Carnaby’s cockatoos, aiding decisions around habitat clearing, protection and conservation.

Permits

All telemetry tracking took place with approval of the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions under permit number TFA 2020-0043, and Murdoch University Animal Ethics Permit No. RW3232/20. Collection of flora was authorised by Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions (Regulation 4 and 8).

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

We acknowledge the financial support and in-kind contribution provided by Main Roads Western Australia, the Public Transport Authority of Western Australia and Iluka Resources Limited.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alex George for assistance with identification of some of the plants. We also thanks members of the Murdoch University Black Cockatoo Conservation Management Team including Dr Anna Le Souëf, Michelle Rouffignac, Rick Dawson, Ryan Carter and Dr Cree Monaghan for assistance with field work or support catching, anaesthetising or attaching tracking devices to study birds.

References

Aldridge HDJN, Brigham RM (1988) Load carrying and maneuverability in an insectivorous bat: a test of the 5% “rule” of radio-telemetry. Journal of Mammalogy 69(2), 379-382.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bouten W, Baaij EW, Shamoun-Baranes J, Camphuysen KCJ (2013) A flexible GPS tracking system for studying bird behaviour at multiple scales. Journal of Ornithology 154(2), 571-580.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bracis C, Bildstein KL, Mueller T (2018) Revisitation analysis uncovers spatio-temporal patterns in animal movement data. Ecography 41(11), 1801-1811.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brundrett MC (2021) One biodiversity hotspot to rule them all: Southwestern Australia—an extraordinary evolutionary centre for plant functional and taxonomic diversity. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 104, 91-122.

| Google Scholar |

DCCEEW (2023) Australia’s bioregions (IBRA). Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Available at https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/land/nrs/science/ibra.

de Souza Leite M, Boesing AL, Metzger JP, Prado PI (2022) Matrix quality determines the strength of habitat loss filtering on bird communities at the landscape scale. Journal of Applied Ecology 59(11), 2790-2802.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Groom C, Warren K, Le Souef A, Dawson R (2015) Attachment and performance of Argos satellite tracking devices fitted to black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus spp.). Wildlife Research 41(7), 571-583.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Joo R, Picardi S, Boone ME, Clay TA, Patrick SC, Romero-Romero VS, Basille M (2022) Recent trends in movement ecology of animals and human mobility. Movement Ecology 10(1), 26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Le Souef AT, Stojanovic D, Burbidge AH, Vitali SD, Heinsohn R, Dawson R, Warren KS (2013) Retention of transmitter attachments on black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus spp.). Pacific Conservation Biology 19(1), 55-57.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maron M, Dunn PK, McAlpine CA, Apan A (2010) Can offsets really compensate for habitat removal? The case of the endangered red-tailed black-cockatoo. Journal of Applied Ecology 47(2), 348-355.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maron M, Evans MC, Walsh J, Mayfield H, Nou T, Davies C, Bamford M, Bamford M, Barrett G, Davis R, Dawson R, Groom C, Johnstone R, Kirkby T, Mawson PR, Mitchell D, Peck A, Riley K, Roper E, Rycken S, Saunders DA, Shephard JM, Stevenson C, Warren K (2021) Better offsets for Western Australia’s black-cockatoos. NESP Threatened Species Recovery Project 5.1. Research findings factsheet, Brisbane.

Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltz D, Smouse PE (2008) A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105(49), 19052-19059.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

R Core Team (2023) ‘R: a language and environment for statistical computing.’ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria). Available at https://www.R-project.org/

Saunders DA (1974) Subspeciation in the White-tailed Black Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus baudinii, in Western Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 1(1), 55-69.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1990) Problems of survival in an extensively cultivated landscape: the case of Carnaby’s cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus latirostris. Biological Conservation 54(3), 277-290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sullivan LL, Michalska-Smith MJ, Sperry KP, Moeller DA, Shaw AK (2021) Consequences of ignoring dispersal variation in network models for landscape connectivity. Conservation Biology 35(3), 944-954.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Western Australian Herbarium (2024) Florabase: browse the Western Australian Flora. Available at https://florabase.dbca.wa.gov.au

Yeap L, Shephard JM, Bouten W, Jackson B, Vaughan-Higgins R, Warren K (2017) Development of a tag-attachment method to enable capture of fine- and landscape-scale movement in black-cockatoos. Australian Field Ornithology 34, 49-55.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |