Movements of adult and fledgling Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Zanda latirostris Carnaby, 1948) from eleven breeding areas throughout their range

Denis A. Saunders A , Peter R. Mawson

A , Peter R. Mawson  B * , Rick Dawson B , Heather Beswick C , Geoffrey Pickup D and Kayley Usher E

B * , Rick Dawson B , Heather Beswick C , Geoffrey Pickup D and Kayley Usher E

A Retired.

B

C Retired.

D Retired.

E

Abstract

Carnaby’s Cockatoo is an endangered species and the subject of a recovery plan.

Our study examined movements of adult and fledgling Carnaby’s Cockatoos from 11 breeding populations in southwestern Australia to establish where the cockatoos spent the non-breeding season (February–May) and sub-adult life-stage.

Data were collected on point-to-point movements from re-sightings and recoveries of cockatoos individually marked with patagial tags or leg bands. Sites were mostly located in the wheatbelt of Western Australia. Distribution patterns in the breeding and non-breeding seasons, including nesting sites were derived from location data from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database.

After breeding, adults and their fledglings moved from breeding areas to higher rainfall areas closer to the west and south coasts of south-western Australia where the food supply is greater and more reliable. Sub-adult cockatoos roam much more widely than adults and utilize foraging habitat not previously recognized as being important to this species.

Important foraging habitat and locations have been identified for breeding populations in the north and south of the range of Carnaby’s Cockatoos.

More conservation attention needs to be focussed on locating additional breeding populations, assessing the viability of these populations, and the extent and condition of their nesting and foraging habitat used during their non-breeding season. Conservation of Carnaby’s Cockatoo depends on the maintenance of remnant native vegetation and revegetation of nesting and foraging habitat throughout its range.

Keywords: Carnaby’s Cockatoo, dispersal patterns, leg bands, non-breeding foraging habitat, patagial tags, Zanda latirostris.

Introduction

Carnaby’s Cockatoo Zanda latirostris Carnaby, 1948 is a large black cockatoo with a white sub-terminal tail band. It is endemic to south-western Australia (Saunders 1974a). As a result of extensive loss of breeding and foraging habitat due to broad-scale removal of native vegetation for agriculture and urban development throughout its range, the species has declined in abundance, with a much reduced range (Saunders 1982, 1990) so that it is now listed as endangered under the Western Australian and Australian Government legislation, and by BirdLife International (2022).

As a result of its conservation status, Carnaby’s Cockatoo is the subject of a recovery plan (Department of Environment and Conservation 2012) that sets out five broad themes of recovery actions for the species. Three of these themes are relevant to this paper: protect and manage important habitat; conduct research to inform management; and engage with the broader community. The recovery plan also specifies the identification of habitat critical to the survival of the species, including habitat essential for successful breeding, together with habitat essential for supporting the species during the non-breeding season.

Since 1969, Carnaby’s Cockatoo has been the subject of much research (Saunders and Dawson 2018). However, there is a paucity of research on movements of breeding Carnaby’s Cockatoos. Saunders (1980) reported on the movements of breeding adults and fledglings from three breeding populations. Since then, there have been two published studies of movements (Groom et al. 2018; Rycken et al. 2024), both based on short-term satellite tracking of cockatoos released after rehabilitation following disease or trauma. In most cases, the cockatoos in those studies were not released at the place they were found when taken into the rehabilitation program. For example, Rycken et al.’s (2024) study was based on 22 cockatoos released from rehabilitation, but none were released on the Swan Coastal Plain where they were collected. Instead they were released at Gingin (78 km north of capture location), Albany (413 km south), and Esperance (696 km southeast). The results of these studies are important as they provide information on how rehabilitated birds integrate into wild flocks after release and how local wild flocks forage on a daily basis. However, they do not provide any information on where breeding birds and their offspring move to after the breeding season, although they identify areas critical for non-breeding season foraging and for support of sub-adults before they commence breeding.

In this study we report on data on the movements of breeding Carnaby’s Cockatoos and their fledglings from 11 breeding sites, studied from 2 to 53 years, throughout the range of the species. We examine where they spent the non-breeding season, how they moved within the wider landscape during the non-breeding season, and establish if there is any overlap in non-breeding season ranges that facilitate genetic exchange between breeding populations. We also map the location of a further 15 breeding sites where nestlings have been banded. This information highlights the regions and remnant native vegetation that breeding Carnaby’s Cockatoos rely on; information essential for conservation management of the species.

Methods

Individual marking

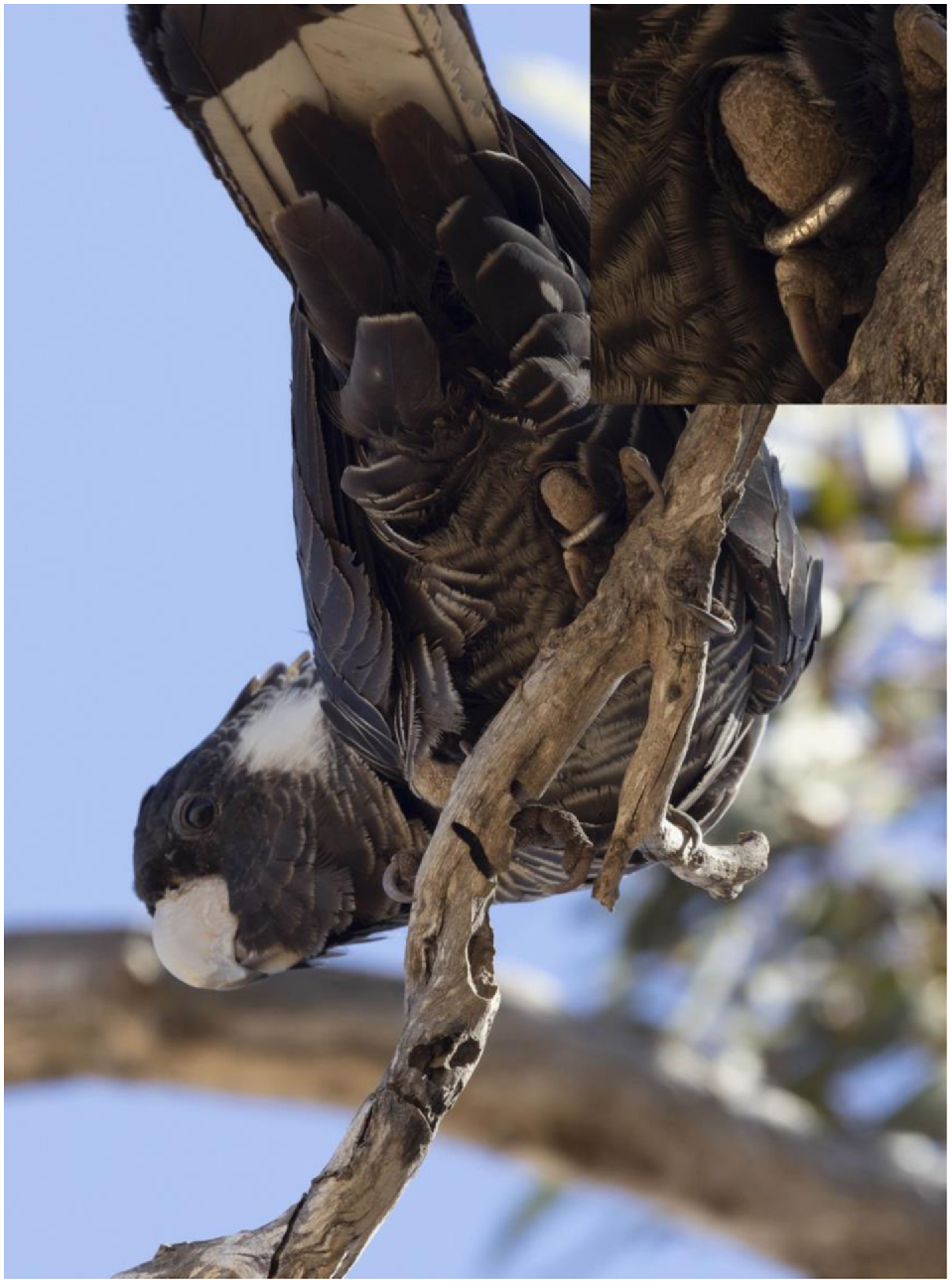

All adult Carnaby’s Cockatoos trapped at their nest sites and all nestlings handled were individually marked. Between 1970 and 1976, birds were individually marked with a stainless steel patagial tag with an individual two-letter combination (Rowley and Saunders 1980) (Fig. 1). However, by 1976 it became clear that cockatoos fitted with patagial tags were being selectively preyed on by wedge-tailed eagles Aquila audax Latham, 1801, and the disadvantages to tagged birds outweighed the benefits to the researcher. Accordingly, the use of patagial tags was discontinued (Saunders 1988). The last patagial tag was recovered along the Hill River on 24 April 2008, 34 years after, and 177 km north-west of where it was placed on a nestling at Manmanning (Saunders and Dawson 2009).

Female BH (stainless-steel patagial tag) at the entrance to her nest hollow at Manmanning in 1972 (photograph Graeme Chapman).

Since 1970, all Carnaby’s Cockatoos handled in their breeding areas have been banded with a uniquely numbered metal leg band of several styles (Figs 2, 3 and 4) issued by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS).

Male 210-03029 banded as a nestling at Coomallo Creek in 1986 and photographed in the same area in September 2021, aged 35. The band size is 21 followed by the individual number 03029. Part of the address ‘Write CSIRO Canberra’ can be seen at the top of the band. It is an early style flat stainless-steel band, still in good condition (photographs Rick Dawson).

Immature male 320-01580 banded as a nestling at Cataby in January 2021 and photographed at Chapman Valley, in February 2024. In this excellent photograph, all of the numbers are in view (photograph Heather Beswick).

Female 320-02076 with the latest band style. The four numbers 2076 identifying her are repeated three times round the band making it more likely to be able to read the numbers. The inset in the top right of the photograph shows the band clearly. The bird was banded on 10 January 2023 in Artificial Hollow #74 at Coomallo Creek (photograph Rick Dawson).

Breeding sites

The 11 breeding sites monitored in this study represent a range of habitats: six were in the wheatbelt; two were in urban areas, and three were in forest. The wheatbelt (see area outlined in Fig. 5) is an area including much of the former range of Carnaby’s Cockatoos. The area has been extensively cleared of native vegetation for the development of cereal cropping and livestock grazing. The birds breed in remnant patches of native woodland and forage in remnant Kwongkan (for this spelling see Hopper 2014) (Saunders 1980, 1982). Kwongkan consists of proteaceous heath and shrublands on sandplain soils.

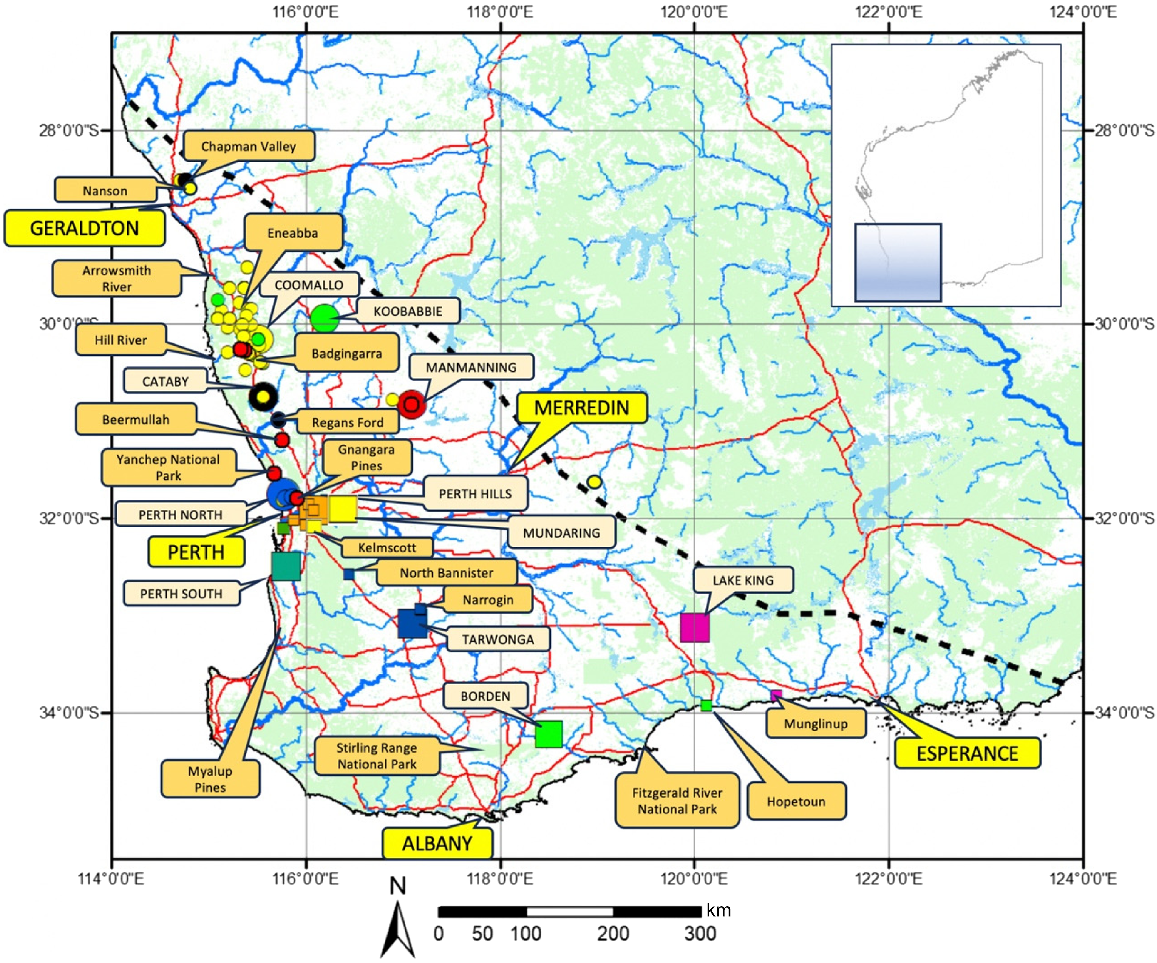

The eleven breeding sites (Fig. 5) are described below in order of their location from north to south of the species’ range.

Locations of the 11 breeding areas, from north to south: Koobabbie (large light green circle); Coomallo Creek (large yellow circle); Cataby (large black circle); Manmanning (large red circle); Perth North (large dark blue circle); Mundaring (large yellow square); Perth Hills (large orange square); Perth South (large dark green square); Tarwonga (large dark blue square); Lake King (large purple square); and Borden (large light green square). The smaller-sized symbols (circles and squares) indicate locations of recoveries/resightings from each of the mentioned breeding areas. The light green shading is the Natural Vegetation Extent Map (from Data WA, WA Dept of Primary Industries and Regional Development). The road network map (red lines) is modified from the published version on Data WA (Main Roads Western Australia). The drainage data are modified from the FAO AQUASTAT database. Location labelling indicates breeding site (buff background), resighting locations (orange background) and main towns (yellow background). Black dashed line indicates eastern margin of the Western Australian wheatbelt.

Koobabbie is a private property in the northern wheatbelt. Carnaby’s Cockatoos nested in natural and artificial hollows in salmon gum Eucalyptus salmonophloia and gimlet E. salubris woodland scattered throughout the cereal–sheep property. A description of the breeding site is provided in Saunders et al. (2014a), together with an account of research conducted on the property. Nestlings were banded at Koobabbie from 2003 to 2018.

Coomallo Creek is a narrow belt of wandoo E. wandoo woodland that stretches 9 km over four private cereal–sheep properties in the northern wheatbelt. Cockatoos were individually marked in the area from 1970 to 1996 and from 2003 to 2023. From 1970 to 1976, birds were marked with both patagial tags and leg bands and then only with leg bands. The study area is described in Saunders (1982) and accounts of research conducted there are presented in Saunders and Ingram (1987), Saunders and Dawson (2018), and Saunders et al. (2020a). Since 2011, 82 artificial hollows have been erected to augment the nearly 100 natural hollows in the study area (Saunders et al. 2020a, 2023). The cockatoos nested in both natural and artificial hollows.

Cataby is a private property on the edge of a large mineral sand mine bounded by a cereal–sheep property and a major highway. Cockatoos nested in both natural and artificial hollows (Johnstone et al. 2015) in a patch of wandoo woodland. Birds were banded there from 2003 to 2023.

Manmanning was centred on a Crown water reserve on the edge of the small hamlet of Manmanning in the central wheatbelt. Cockatoos nested in natural hollows in salmon gum woodland in the reserve and in scattered woodland patches on private cereal–sheep properties surrounding the reserve. Cockatoos were individually marked with patagial tags between 1970 and 1976. As a result of loss of foraging habitat, the population ceased breeding in the area by 1978 (Saunders 1982).

Perth North is the main campus of Edith Cowan University, in the northern outskirts of Perth, the capital city of the state of Western Australia. The cockatoos nested in natural nest hollows in tuart E. gomphocephala stag trees and artificial nest hollows. Birds were banded from 2015 to 2021.

Perth Hills is a private property on the eastern outskirts of Perth. The cockatoos nested in artificial hollows in marri Corymbia calophylla woodland. Birds were banded from 2012 to 2023. In addition to being banded, several Perth Hills birds that were subsequently injured or diseased were rehabilitated and fitted with passive integrated transponders (PIT tags), inserted deep in the breast muscle on the left side of the keel.

Mundaring is a reserve on the on the eastern outskirts of Perth. Cockatoos nested in natural hollows in jarrah E. marginata/marri forest and woodland with an understorey of Banksia.

Perth South is a private property on the southern outskirts of Perth, where the cockatoos nested in artificial hollows within a largely suburban landscape retaining some small areas of natural tuart and marri woodland. Birds were banded there from 2022 to 2023.

Tarwonga is on several patches of Highbury State Forest and Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage reserve land in which the cockatoos nested in natural hollows in wandoo woodland. Research was conducted in the area in 1970–1972, during which time the cockatoos were marked with patagial tags. The breeding population was subject to illegal taking of nestlings; as result, the study was discontinued in 1973.

Lake King is a private cereal–sheep property, south-east of the town of Lake King in the southern wheatbelt. The birds nested in natural and artificial hollows in salmon gum woodland scattered around the property. Cockatoos were banded there in 2008 and 2015.

Borden is a private cereal–sheep property. The birds nested in natural and artificial hollows in a single patch of wandoo woodland. Cockatoos were banded from 2008 to 2023.

Point-to-point movements

We defined a point-to-point movement as where a cockatoo: moved from its breeding area and was recorded more than 10 km from the breeding area; moved from one area to another area more than 10 km from its previous recorded position; or moved back to its breeding area. For example, a cockatoo moving from Coomallo Creek to Hill River after breeding or fledging would count as one point-to-point movement. If it spent several months foraging along the Hill River and was observed one or more times during that period, the recordings along the Hill River would not constitute a series of point-to-point movements. However, if it was recorded more than 10 km from Hill River, that would constitute a point-to-point movement, as would it returning to its breeding area. A point-to-point movement could occur over a short time (within days) or could be the result of two sightings months or years apart.

Data on point-to-point movements

Data on movements were gathered through a variety of methods. Movements of birds individually marked with patagial tags were established from tags seen or found by members of the public, returning them to CSIRO researchers. This enabled researchers to visit areas that tagged cockatoos were seen or recovered from, and search for tagged cockatoos. Initially, resighting of cockatoos relied on visual observations with telescopes or binoculars or trapping. More recently, digital photography and telephoto lenses allow reading of bands and also provide a permanent positive record (Saunders et al. 2011). One observer in the north of Perth provided water for the birds, and photographed banded birds. In addition, this observer and one of us (KU) installed a PIT tag reader underneath a water bowl that recorded the visits of any birds fitted with PIT tags.

Distribution of Carnaby’s Cockatoos during the breeding and non-breeding seasons

The Carnaby’s Cockatoo breeding population at Coomallo Creek has been subject to the most detailed long-term research out of the 11 populations described in this study (Saunders and Ingram 1987; Saunders and Dawson 2018). At Coomallo Creek, the earliest eggs were laid was in the week 5–11 June and the latest in the week 18–24 December (n = 1887; 1969–2023) (Saunders, Dawson, and Mawson unpubl. data). Based on these data, we have defined the breeding season as June–January (inclusive) and the non-breeding season as February–May (inclusive). Although point-to-point movements based on individually marked individuals provide information on patterns of movement, they only cover 11 breeding areas. In addition to these 11 locations, we have banded nestlings at a further 15 locations, however, we have no band resightings/recoveries of cockatoos from these areas.

To compare the distributions of Carnaby’s Cockatoos during the breeding and non-breeding seasons, we used 20,142 location records (1999–2023) from the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ (2024) Threatened and Priority Database Search for Carnaby’s Cockatoo prepared by the Department’s Species and Communities Program for this paper and accessed 27 May 2024. Along with all recorded locations, we plotted locations where observers believed cockatoos were breeding and divided the location data into breeding and non-breeding seasons in order to capture the distribution of cockatoos after breeding.

As is common with citizen science databases, data are biased by having more observations from urban areas where there are more observers. We have also added bias by dividing the data into eight-month (breeding) and four-month (non-breeding) periods, with more observations likely from the longer period. We have reduced these biases by spatial point thinning of observations using the algorithm provided in the ETGeowizards™ software package (https://www.ian-ko.com/) which creates a set of points based on clustering of location data, but with a separation distance of 0.1-° or less. We found this to be better at preserving point locations than the grid cell method used by Saunders and Pickup (2023). This method records whether a bird was observed or not in each cluster and, optionally, the number of observations in the cluster. In this study, we only analysed presence or absence values.

Results

A total of 360 adult and 2553 nestling Carnaby’s Cockatoos were individually marked at the 11 breeding areas between 1970 and 2023. Two hundred and thirty-nine of these individuals generated 535 point-to-point movements (Table 1), ranging from one movement from each of two sites (Perth South and Lake King) to 467 from and to Coomallo Creek.

| Breeding locations | Years of study | # Adults marked | # Nestlings marked | # individuals moved | # movements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koobabbie | 2003–2018 | 0 | 92 | 2 | 2 | |

| Coomallo Creek | 1970–1996 | 278 | 774 | 178 | 447 | |

| Coomallo Creek | 2003–2023 | 10 | 1105 | 20 | 20 | |

| Cataby | 2003–2023 | 8 | 231 | 2 | 2 | |

| Manmanning | 1970–1976 | 52 | 38 | 16 | 39 | |

| Perth North | 2015–2021 | 0 | 24 | 5 | 5 | |

| Perth Hills | 2012–2019 | 0 | 32 | 8 | 11 | |

| Perth South | 2022–2023 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mundaring | 2015–2023 | 0 | 38 | 2 | 2 | |

| Tarwonga | 1970–1972 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 3 | |

| Lake King | 2008/2015 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Borden | 2008–2023 | 10 | 201 | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 360 | 2553 | 240 | 535 |

Of these 535 point-to-point movement records, 32 (6.0%) were made by members of the public (Table 2) and the other 503 were established by researchers connected with the study sites. Of the 386 point-to-point movements by adult cockatoos, 4 (1.0%) observations were made by members of the public, as were 28 (18.9%) observations of the 148 point-to-point movements by fledglings. Of the 32 movements established by members of the public, 29 birds (90.6%) were found dead (drowned in stock troughs, hit by vehicles, electrocuted, died in a day of extreme heat, or shot), two were found injured and taken into rehabilitation, and one was photographed with the band identified from the photograph.

| Breeding locations | Years of study | # Adult movements | # Adult movement records from non-researchers | # fledgling movements | # Fledgling movement records from non-researchers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koobabbie | 2003–2018 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Coomallo Creek | 1970–1996 | 348 | 4 | 99 | 8 | |

| Coomallo Creek | 2003–2023 | 2 | 0 | 18 | 7 | |

| Cataby | 2003–2023 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Manmanning | 1970–1976 | 36 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Perth North | 2015–2021 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | |

| Perth Hills | 2012–2019 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 3 | |

| Perth South | 2022–2023 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mundaring | 2015–2023 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Tarwonga | 1970–1972 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Lake King | 2008/2015 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Borden | 2008–2023 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 386 | 4 (1.0%) | 149 | 28 (18.9%) |

Koobabbie

Two fledglings from Koobabbie, banded in 2008, were sighted outside the breeding area (Fig. 5). One, a female, was seen in a flock of around 400 birds east of Eneabba in September 2012, nearly 4 years after she fledged. The other was a male seen in the Coomallo Creek breeding area in November 2010, 2 years after fledging.

Coomallo Creek

The 447 movements from and to the breeding area recorded in the period between 1970 and 1996 were concentrated west of the breeding area, between Badgingarra in the south and the Arrowsmith River in the north (Fig. 5). Many cockatoos were seen at the same locations, hence the number of locations shown in Fig. 5 is much less than the number of point-to-point movements. One fledgling (sex unknown) was found dead outside of this range, 155 km from Coomallo Creek, west of Manmanning in December 1976, one year after fledging (Fig. 5). Between 1970 and 1996, cockatoos were recorded in flocks of 150–400+. The majority of the 20 movements generated from 2003 to the present were in the same area that the cockatoos ranged over between 1970 and 1996. Flock sizes recorded were the same as the earlier period. One female that fledged at Coomallo Creek in 2017 was found breeding at Cataby in November 2022. Four cockatoos were recorded outside this area. One (sex unknown) was hit by a car at Padbury (a northern suburb of Perth), 214 km south of the breeding area, less than a month after fledging. The other three were photographed at Chapman Valley, 260 km north of the breeding area, 6 months after fledging (female) and 2 years after fledging (male and female) and one female was photographed near Nanson, 254 km north north-west of the breeding area, 8 years after fledging.

Cataby

One male fledgling was photographed at Chapman Valley, two years after fledging. Another fledgling (sex unknown) was found dead at Regans Ford, 32 km south of Cataby, 10 months after fledging (Fig. 5).

Manmanning

Four locations were identified in the 39 movements from and to the breeding area (Fig. 5). The first location was Beermullah, 166 km west of the breeding area, where an adult female was shot one month after breeding. The second location was Yanchep National Park, 207 km west of the breeding area, where the birds gathered in flocks of over 1000. The third was the Gnangara Pine (Pinus pinaster) Plantation between Perth and Yanchep, with the birds moving between Yanchep National Park and the pines at Gnangara (38 km). The fourth location was along the Hill River, 235 km west of Manmanning, an area frequented by birds from Coomallo Creek, where an adult female was recorded there 6 years after she had been banded and tagged at Manmanning in 1970. Another cockatoo was recorded in the same locality through the finding of a patagial tag, 34 years after it had been placed on the bird (Saunders and Dawson 2009).

Perth North

Five fledglings (two females, two males, and one sex unknown) moved from the Edith Cowan Campus at Joondalup and were recorded around Gnangara Pine Plantation, less than 15 km north-east of their breeding area (Fig. 5).

Perth Hills

All 11 movements by fledglings (four females, five males) from this breeding area were westwards onto the Swan Coastal Plain within 35 km of the breeding area (Fig. 5).

Mundaring

Two female fledglings were photographed at Kelmscott (Fig. 5), 20 km south of the breeding area feeding on macadamia (Macadamia sp.) nuts, 4 and 5 months after fledging.

Perth South

One female fledgling recorded from this breeding area was hit by a car on the Swan Coastal Plain 48 km north of its breeding area and taken into rehabilitation (Fig. 5) shortly after fledging.

Tarwonga

Three fledglings (sex unknown) were recorded moving from the breeding area (Fig. 5). One was killed by a car at North Bannister, 104 km north-west of the breeding area less than 2 months after fledging. The other two were shot feeding on almond nuts (Prunus amygdalus) in residential backyards in Narrogin, 20 km north-east of the breeding area, 6 months and 1+ year after fledging.

Lake King

Of the two nestlings banded at the breeding area, one (sex unknown) was found dead at Munglinup, 102 km south-east of the breeding area, over a year after fledging. This bird was among 63 Carnaby’s Cockatoos killed at Munglinup on a day of extreme heat (Saunders et al. 2011).

Borden

One fledgling (sex unknown) was recorded by a member of the public at Hopetoun, on the coast 154 km east-north-east from the breeding area, and a second was also recorded by another member of the public 10 km west of the breeding area (Fig. 5).

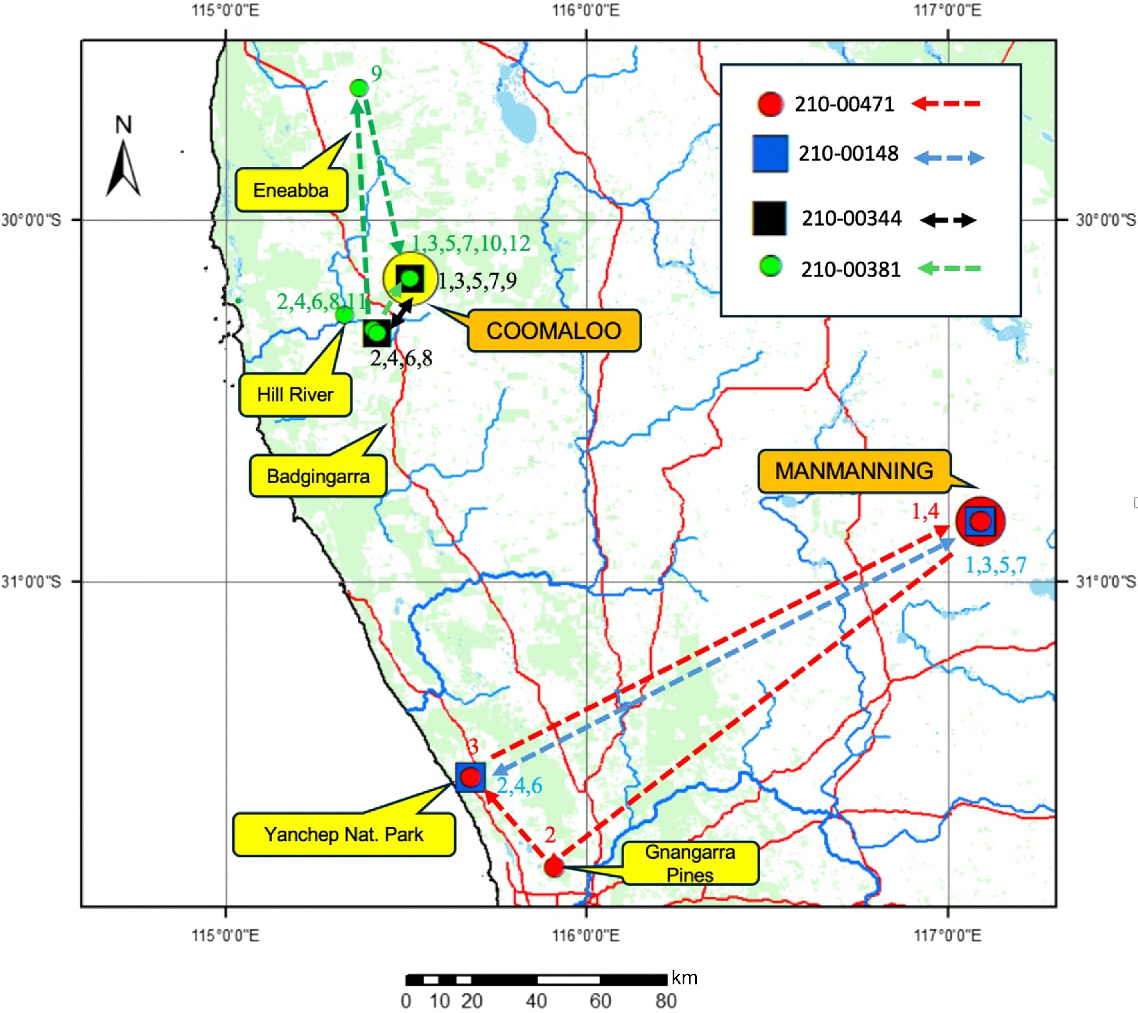

Outward and return movements

Resighting records were obtained for four Carnaby’s Cockatoos that undertook one or more outward movements away from two breeding areas to non-breeding areas and were then resighted at the same breeding site in the year or years following (Table 3, Fig. 6). These were two adult males (>4 years of age at the time of banding) that were banded at Manmanning in 1971 and 1973 and two adult females banded at Coomallo Creek in 1973.

| 210-00148 Adult male (Fig. 6; small blue squares, numbers, and arrows): | |

| #1 banded on 3/11/1971 in Manmanning breeding area; | |

| #2 resighted on 20/03/1974 in Yanchep National Park (seen 15/01–22/04/1974 on Swan Coastal Plain); | |

| #3 resighted on 21/11/1974 in Manmanning breeding area; | |

| #4 resighted on 15/01/1975 Yanchep National Park; | |

| #5 resighted on 2/10/1975 in Manmanning breeding area; | |

| #6 resighted on 3/03/1976 Yanchep National Park; and | |

| #7 resighted on 9/09/1976 in Manmanning breeding area. | |

| 210-00471 Adult male (Fig. 6; small red circles, numbers and arrows): | |

| #1 banded on 4/12/1973 in Manmanning breeding area; | |

| #2 resighted on 8/04/1975 at Gnangara Pine Plantation; | |

| #3 resighted on 17/06/1975 in Yanchep National Park, which lies immediately to the west of Gnangara Pine Plantation (8/04–17/06/1975 on the Swan Coastal Plain); and | |

| #4 resighted on 10/09/1975 again at the Manmanning breeding area. | |

| 210-00344 Adult female (Fig. 6; small black squares, numbers black arrows): | |

| #1 banded 7/10/1973 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #2 resighted on 7/02/1974 at Hill River; | |

| #3 resighted on 20/08/1974 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #4 resighted on 9/01/1975 at Hill River; | |

| #5 resighted on 13/08/1975 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #6 resighted on 30/01/1976 at Hill River; | |

| #7 resighted on 28/09/1976 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #8 resighted on 25/01/1977 at Hill River; and | |

| #9 resighted on 22/11/1977 in Coomallo Creek breeding area. | |

| 210-00381 Adult female (Fig. 6; small green circles, numbers, and arrows): | |

| #1 8/11/1973 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #2 14/02/1974 at Hill River (seen 14/02–2/03/1974 foraging along Hill River); | |

| #3 21/08/1974 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #4 2/01/1975 at Hill River (seen 2/01–5/02/1975 foraging along Hill River); | |

| #5 25/09/1975 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #6 9/01/1976 at Hill River; | |

| #7 6/10/1976 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #8 25/01/1977 at Hill River; | |

| #9 25/03/1977 at White Horse Springs; | |

| #10 20/09/1977 in Coomallo Creek breeding area; | |

| #11 20/11/1977 at Hill River; and | |

| #12 11/09/1980 in Coomallo Creek breeding area. |

# indicates sequential sightings of each individual. Movements are shown in Fig. 6.

Outward and return movements of two adult Carnaby’s Cockatoos from the Manmanning breeding area (large red circle), and two adults from the Coomallo Creek breeding area (large yellow circle). Numbers indicate sequential sightings of each individual (Table 3).

Breeding locations

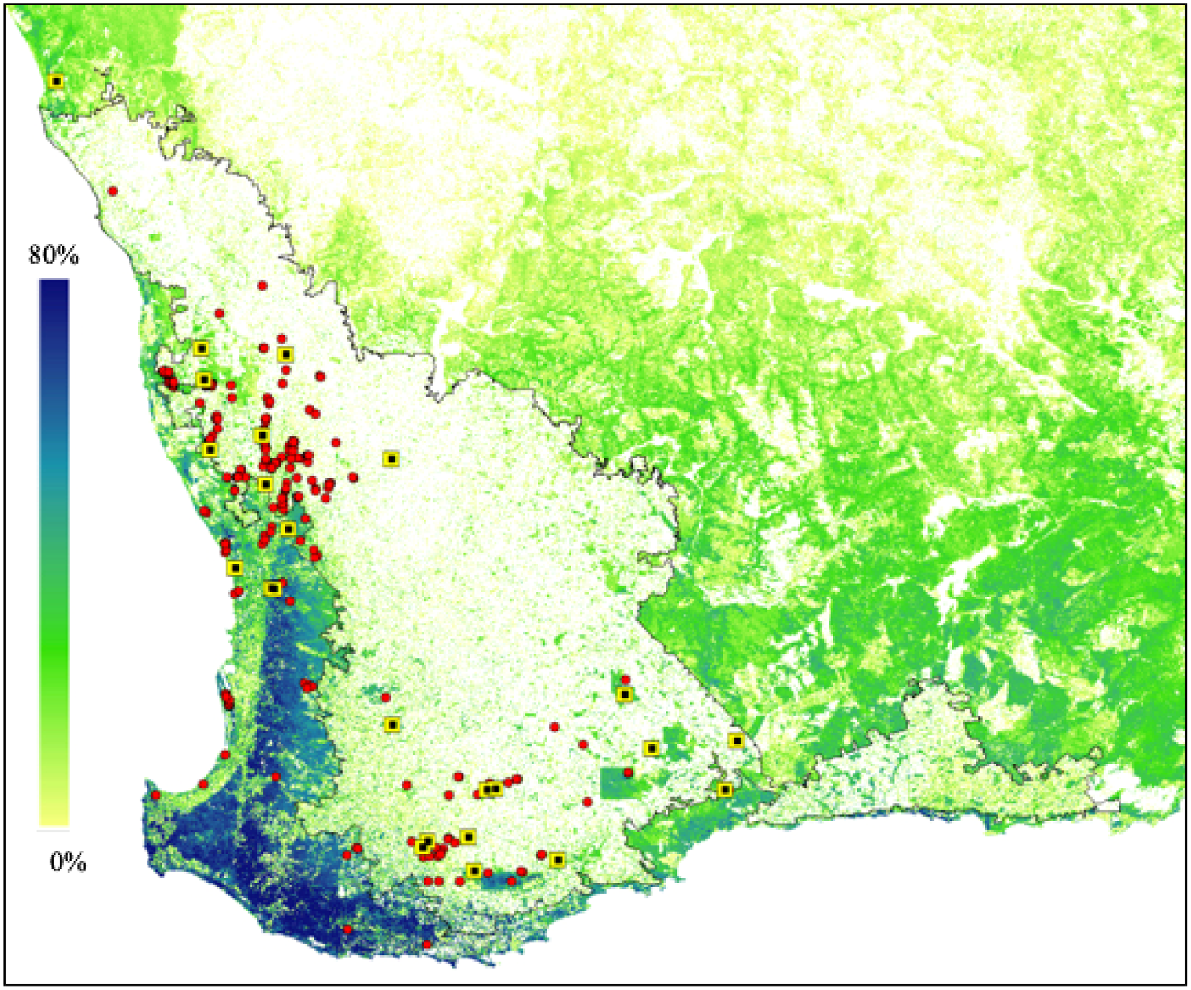

The 26 locations where we have banded nestlings are shown in Fig. 7, together with the locations observers who contributed to the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database believed Carnaby’s Cockatoos were breeding.

Location of Carnaby’s Cockatoo breeding sites. Those sites where nestlings have been banded are indicated by black squares within yellow squares and records from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database are indicated by red circles. The native vegetation layer showing persistent green vegetation is from Searle et al. (2022) and the colour scale is percentage of canopy cover. Coordinates and scale are as shown in Fig. 5. The black outline of the wheatbelt is from the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development’s Wheatbelt of WA (DPIRD-04) https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/nl/dataset/wheatbelt-of-wa-dpird-028 accessed 29 May 2024.

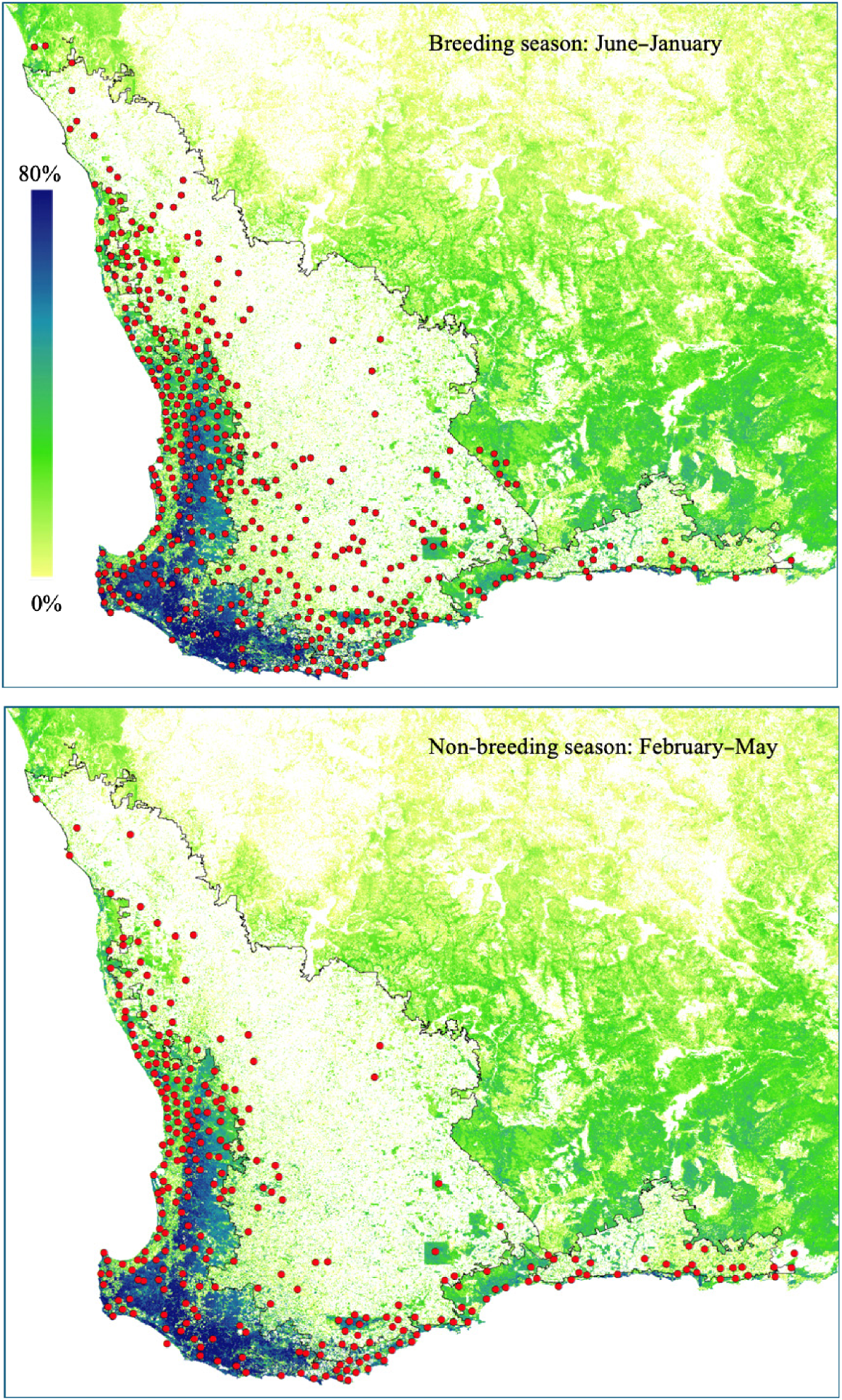

Comparison of the distributions of Carnaby’s Cockatoos in the breeding and non-breeding seasons

Based on the areas we have banded nestlings, Carnaby’s Cockatoo breed over much of their range (Fig. 8). Comparison of the distributions of the cockatoos in the breeding and non-breeding seasons demonstrates the birds in the northern part of their range move west closer to the coast concentrating on areas of remnant native vegetation. Birds from the southern part of their range follow a similar dispersal pattern moving closer to the south coast, where they concentrate on remnant native vegetation. These dispersal patterns are the same as those indicated by point-to-point movements of cockatoos from the 11 breeding areas.

Distribution of Carnaby’s Cockatoos (red circles) in the breeding season (June–January) and in the non-breeding season (February–May). Location data are from Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database. The native vegetation layer showing persistent green vegetation is from Searle et al. (2022) and the colour scale is percentage of canopy cover. Coordinates and scale are as shown in Fig. 5. The black outline of the wheatbelt is from the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development’s Wheatbelt of WA (DPIRD-04) https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/nl/dataset/wheatbelt-of-wa-dpird-028 accessed 29 May 2024.

Discussion

Breeding areas

Carnaby’s Cockatoos commence breeding at 3 or 4 years old (Saunders 1982; Dawson et al. 2013) and continue breeding annually. Based on long-term studies at Coomallo Creek and Manmanning (Saunders 1982; Saunders et al. 2018) many females commence breeding in the area from which they fledged. They typically breed in the same area each year. After fledging their young, pairs leave the breeding area, with their offspring, along with those breeding pairs that had unsuccessful breeding attempts. All of the cockatoos then form foraging flocks, together with sub-adults from previous years, for the non-breeding season (Saunders 1980). It is reasonable to assume the species exhibits this pattern of breeding behaviour throughout their breeding range.

Of interest is the absence of breeding and foraging sites in the central wheatbelt (Figs 7 and 8). This reflects the absence of birds as a result of broad-scale clearing of native vegetation with a major contraction in range and abundance (Saunders 1990, 1991; Saunders and Ingram 1987). As the background images to Figs 7 and 8 show, persistent green vegetation, which we use as a surrogate measure of tree cover, is sparser in this area and also occurs in smaller patches, indicating less breeding and foraging habitat.

Non-breeding season ranges

Although there are a number of other Carnaby’s Cockatoo breeding locations known [e.g. Saunders 1986, Saunders et al. 2014b; Murchison House Station; Moora; Piawanning; Wongan Hills; Mogumber; Bindoon; Julimar State Forest; Dragon Rocks Nature Reserve; Kwobrup Nature Reserve; Badgebup Nature Reserve; Cocanarup Timber Reserve; and Tunney Nature Reserve; (listed north–south) RD, PRM unpubl. data], and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database, we were only able to access movement data from the 11 reported on in this paper. However, as shown in Fig. 5, these locations cover much of the species’ breeding range.

Most movement data came from breeding populations north of a line between Perth and Merredin. After breeding, Carnaby’s Cockatoos leave their breeding areas and move to areas of higher rainfall closer to the west coast (Figs 5, 6, 7 and 8; Saunders 1980). The areas they frequent have large areas of remnant native vegetation, and being predominantly seed eaters, the cockatoos must have daily access to water. Cockatoos from Coomallo Creek frequent the Hill and Arrowsmith Rivers, which have riparian native vegetation, including the most northerly stands of marri on which they feed and roost. Water is available in pools along the rivers and in stock troughs in adjacent agricultural properties. In addition, there are extensive areas of woodland and Kwongkan in which the birds forage (Saunders 1980) (Figs 7 and 8). The cockatoos from Coomallo Creek and Cataby can range over wide areas, as far north as Chapman Valley (Fig. 5) where they have been recorded feeding on native vegetation and introduced paddy melon Citrullus lanatus and wild radish Raphanus raphanistrum (HB pers. obs.), both agricultural weeds, and as far south as Perth. Rycken et al. (2024) found that rehabilitated birds released at Gingin (99 km south of Badgingarra) demonstrated the same foraging pattern, following Gingin Brook, feeding on native vegetation, macadamia nuts, and wild radish, and watering in river pools and stock troughs.

Birds from the central wheatbelt (Manmanning) also moved to Perth, where commercial pine plantations such as those at Gnangara and Pinjar were important foraging areas in which the cockatoos spent much of the non-breeding season (Saunders 1974b; Stock et al. 2013). They also foraged on remnant Kwongkan (Saunders 1980). Cockatoos from the Perth area (Perth North, Perth Hills, and Perth South), appeared to remain on the Swan Coastal Plain, feeding on pines, remnant native vegetation, and some introduced flora (Saunders 1980; Groom 2015). Limited data from the Tarwonga site indicated the cockatoos fed on almond nuts in the nearby town of Narrogin as well as moving west into the jarrah forests and towards the Swan Coastal Plain. Saunders (1980) demonstrated the commercial pine plantations scattered through the jarrah/marri forest of the south west were important food sources for Carnaby’s Cockatoos. For example, one of these plantations at Myalup was visited by the birds throughout the year (Forest Officer February 1972 pers. comm.) and the birds still use Myalup plantation (Caretaker Myalup Cottages April 2024 pers. comm.).

Limited data are available on the movements of cockatoos from breeding areas in the south of the species’ range (Lake King and Borden). However, two of the three point-to-point movements, along with data from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database (Fig. 8) indicate the birds moved to the south coast where there were extensive areas of remnant native vegetation, particularly woodland and Kwongkan. The importance of native vegetation to the birds was demonstrated by Rycken et al. (2024) who found the birds released at Albany foraged in remnant native vegetation on private properties and in Porongurup National Park (48 km north of Albany) and birds released at Esperance foraged in remnant native vegetation and pines along the coast as far west as Munglinup (108 km west) and as far east as Condingup (75 km east).

Our study has demonstrated the value of being able to resight or recover marked Carnaby’s Cockatoos from known breeding sites. Individually marked fledglings moved with their parents from their natal breeding area in eucalypt woodlands at the end of the breeding season, west or south to the nearest coastal feeding areas (Figs 5 and 6) that are dominated by woodland and Kwongkan. Sub-adult birds (aged 1–3 years) were then recorded moving over wider coastal areas during the years before they reached sexual maturity, but still showing a preference for areas supporting extensive remnant native vegetation in proximity to freshwater rivers and lakes. Adults were recorded making annual journeys across the same habitat, moving from breeding areas to the nearest areas of coastal remnant native vegetation (Fig. 6) before returning to the breeding areas for the next breeding season.

When the movements of fledgling, sub-adult, and adult Carnaby’s Cockatoos reported here are considered together with movement data from satellite and GPS studies of Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Groom et al. 2014, Groom 2015; Rycken et al. 2024) and data from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ Threatened and Priority Database, it is evident that habitat critical for this species consists of distinct areas during the breeding and non-breeding seasons, which may be separated by distances of 30–200 km. Saunders et al. (2014b) demonstrated the need for good quality and quantity of foraging habitat within 12 km of breeding sites. However, our study and that of Rycken et al. (2024) show that conserving key breeding populations requires the conservation of foraging habitat on a scale at least one order of magnitude greater than 12 km. Without accurate knowledge of the movements of adult Carnaby’s Cockatoos and their offspring after the completion of each breeding season and appropriate vegetation mapping, it is impossible to conserve all of the resources the species requires.

Kwongkan that supports numerous proteaceous species (Beard 1982) is the preferred foraging habitat for Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Saunders 1980; Valentine et al. 2014; Johnston et al. 2016). These vegetation associations are well adapted to fire, but the drying climate that the south-west of Western Australia has been experiencing over the past 50 years has been contributing to more frequent, intense, and extensive wildfires. This change in the impact of fire on key foraging areas frequented by Carnaby’s Cockatoos means that extent and connectivity of foraging habitat may become more difficult to maintain. Managing fire (wildfire and prescribed burning) to mitigate risk to farming properties and infrastructure adjacent to Kwongkan (regardless of land tenure) is already challenging, and further research is likely to help inform how these vegetation associations can be conserved in the changing climate regime. As ongoing climate change lengthens fire seasons (i.e. unseasonal wildfires become more common) and managed fires are implemented further outside historically typical fire seasons, post-fire seedling recruitment may become more vulnerable to failure, causing shifts in plant community composition towards those with fewer species solely dependent on seeds for regeneration (Miller et al. 2021).

Genetic exchange

The overlap of foraging ranges of Carnaby’s Cockatoos from different breeding sites during the non-breeding season (Fig. 5), means there are opportunities for genetic exchange between most of the key breeding populations we report on. This was demonstrated by the resighting of cockatoos from Koobabbie, Coomallo Creek, Cataby, and Manmanning in the northern wheatbelt, and cockatoos from Lake King and Borden in the south, combined with recorded movements of cockatoos from Esperance (Rycken et al. 2024). Many females display fidelity to their natal area (Saunders et al. 2018), mating with males in foraging flocks who may not have fledged from their natal area. White et al. (2014) used analyses of DNA to demonstrate that there was no genetic structuring in Carnaby’s Cockatoos from breeding sites from Koobabbie south to Albany, but they suggested that the fragmentation of pre-settlement habitat associated with the establishment of broad-acre cereal cropping may be leading to genetic drift in Carnaby’s Cockatoo populations located east of Albany. The results reported here indicate that there may still be enough movement of cockatoos from breeding sites such as Lake King, and possibly Borden, to allow genetic exchange with breeding populations located further east due to the use of non-breeding habitat in the Munglinup area (Fig. 5).

Community engagement with research

A strong network of engaged community members has been key to the number of recoveries/resightings of patagial tags and leg bands (5.5% of recoveries, Table 2). There was a difference in recovery rates between adult cockatoos (1.0%) and fledglings (18.9%), consistent with the much higher reported mortality rates of fledglings (Saunders 1982). The importance of community engagement is evident in the discovery of remote locations used by sub-adult and adult Carnaby’s Cockatoos in areas north of Coomallo Creek (Figs 5 and 6). In the Perth metropolitan area, the majority of more than 300 injured and dead black cockatoos (of three species) admitted to the Perth Zoo Veterinary Department each year (Le Souëf et al. 2015) are recovered by members of the community, or an observer has notified one of two dedicated black cockatoo rehabilitation services based in Perth to instigate the recovery of the cockatoo(s).

The involvement of community members in research on Carnaby’s Cockatoos, and their continued engagement, has been facilitated by advances in modern technology such as cameras with telephoto lenses, image stabilisation functions, and high-resolution imaging. In order to increase community engagement in resighting individually marked cockatoos, Dawson and Saunders (2014) challenged photographers to look for leg bands when photographing cockatoos; a challenge that seems to have been taken up.

Small numbers of recoveries of leg bands have been provided after community members have photographed dead cockatoos and their leg bands with mobile phones and shared the images with one of us. This has several advantages in that species identification, sex of the cockatoo, leg band number, and a GPS location for the recovery can all be obtained. The ease with which even the most inexperienced mobile phone user can achieve this, when combined with the likely short turn-around time for receiving feedback from the person who placed the leg band on the bird, helps encourage community members to make subsequent contributions.

Movements of other Zanda and Calyptorhynchus species

No other species of black cockatoo (genera Zanda and Calyptorhynchus) has been leg banded/tagged to anywhere near the same extent as Carnaby’s Cockatoo. Seventy Baudin’s Cockatoos (Z. baudinii Lear, 1832) have been banded, and all were birds that had been sick or injured in some way, treated, rehabilitated, and then released. Of those 70, only three were recovered, all in close proximity to release sites. Similarly, less than 20 Forest Red-tailed Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus naso Gould, 1837) nestlings have been banded and only one of those recovered/resighted. More than 400 rehabilitated Forest Red-tailed Cockatoos (age >1 year) have been banded and released, nearly all into the greater Perth metropolitan area, and 39 have been recovered/resighted; all within the metropolitan area (PRM, RD unpubl. data). Fifteen Yellow-tailed Cockatoos (Z. funerea Shaw, 1794) have been banded and the one recovery was 23 km from where it was banded. After Carnaby’s Cockatoos, Glossy Cockatoos (C. lathami Temminck, 1807) have the most birds banded; 643 with 59 recoveries, all within 43 km of where they were banded on Kangaroo Island (Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Database https://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/biodiversity/abbbs/abbbs-search.pl accessed 19 October 2024). None of these studies provide useful information for comparison with our study on movements of Carnaby’s Cockatoos.

Conservation implications

The current recovery plan for Carnaby’s Cockatoo is now 12 years old (Department of Environment and Conservation 2012) and is being revised. Our study provides an opportunity to make better informed plans to conserve important habitat used by adult cockatoos and their attendant offspring during the non-breeding season as well as habitat used by the sub-adult birds in the period of their life when they select their mates and before they commence breeding.

Future research needs to be focused on finding additional breeding areas, assessing the size of each breeding population, the health of their nestlings (Saunders et al. 2020b), their breeding success, and the availability and condition of nest hollows (Saunders et al. 2014c, 2020a). Are nesting hollows limiting the population at any or all sites, and if so, which breeding sites are priority sites for on-ground remediation? If so, are artificial hollows needed and/or should derelict natural hollows be renovated? In addition, more studies on the long-term movement patterns of birds to and from their breeding areas are needed. These studies are necessary to establish if revegetation programs are needed for both nesting habitat and foraging habitat in proximity to those breeding sites, and at more remote locations where non-breeding cockatoo populations congregate.

Any future development plans for commercial macadamia and almond plantations within the range of Carnaby’s Cockatoos need to acknowledge the potential for them to feed in the plantations once they are established. Accordingly, development plans should only be approved if the plantations are netted or other non-lethal methods to exclude cockatoos are applied.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted under all appropriate animal ethics and handling permits required. Research from 1970 to 1996 was conducted under CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research and Western Government permits, and Australian Bird and Bat Banding Authority #A418. Research from 2003 to 2023 was conducted under Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation, and Attractions Animal Ethics Committee project approval #2014-23, #2017-21, #2020-10C and #2023-09G); Scientific Licenses SC001289 and SC001405 held by RD and Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, Section 40 Authorisation TFA2019-0111-3 held by RD; Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Banding Authority Number #1862 held by PRM. We are grateful to many people for their support during the conduct and publication of this research: particularly John Ingram (CSIRO Wildlife Research) (1970–1996) for technical support; the following people for access to their properties and in some cases for accommodation; Alison and John Doley; Raffan family; Paish family; Colin McAlpine; Hayes family; Basil and Mary Smith; Campbell family; Kennedy family; Price family; Ron Johnstone OAM and Tony Kirkby for providing data for their Cataby and Mundaring study areas; Claire Sands (WA Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions) for providing observer records for Carnaby’s Cockatoos; Dr Nathalie Casal for the considerable time and effort she spent photographing bands, downloading and cataloguing records, and funding purchases of recording equipment; Jarna Kendle, Karen Riley, and Dr Sam Rycken for critical comment on a pre-submission version of the manuscript; and Emeritus Professor Mike Calver and two anonymous reviewers for critical comments on the submission of the manuscript to the journal.

References

BirdLife International (2022) Zanda latirostris. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2022: e.T22684733A212974328. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T22684733A212974328.en [accessed 01 March 2024]

Dawson R, Saunders DA (2014) Individually marked wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos: a challenge and opportunity for keen photographers. Western Wildlife 18(1), 4-5.

| Google Scholar |

Dawson R, Saunders DA, Lipianin E, Fossey M (2013) Young-age breeding by a female Carnaby’s Cockatoo. The Western Australian Naturalist 29, 63-65.

| Google Scholar |

Groom C (2015) Roost site fidelity and resource use by Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris on the Swan coastal plain, Western Australia. PhD Thesis, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia. Available at http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/roost-site-fidelity-and-resource-use-by-carnabys-cockatoo-calyptorhynchus-latirostris-on-the-swan-coastal-plain-western-australia(930854f0-6ff5-4b4d-b659-544fb3dc95e9).html

Groom CJ, Mawson PR, Roberts JD, Mitchell NJ (2014) Meeting an expanding human population’s needs whilst conserving a threatened parrot species in an urban environment. The Sustainable City IX(2), 1199-1212.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Groom CJ, Warren K, Mawson PR (2018) Survival and reintegration of rehabilitated Carnaby’s Cockatoos Zanda latirostris into wild flocks. Bird Conservation International 28, 86-99.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Johnston TR, Stock WD, Mawson PR (2016) Foraging by Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo in Banksia woodland on the Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia. Emu - Austral Ornithology 116, 284-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Johnstone RE, Kirkby T, Mannion M (2015) Trial on the use and effectiveness of artificial nest hollows for Carnaby’s Cockatoo at Cataby, Western Australia. Western Australian Naturalist 29, 250-262.

| Google Scholar |

Le Souëf A, Holyoake C, Vitali S, Warren K (2015) Presentation and prognostic indicators for free-living black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus spp.) admitted to an Australian zoo veterinary hospital over 10 years. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 51, 380-388.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Miller RG, Fontaine JB, Merritt DJ, Miller BP, Enright NJ (2021) Experimental seed sowing reveals seedling recruitment vulnerability to unseasonal fire. Ecological Applications 31, e02411.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rowley I, Saunders DA (1980) Rigid wing-tags for cockatoos. Corella 4, 1-7.

| Google Scholar |

Rycken S, Warren KS, Yeap L, Jackson B, Mawson PR, Dawson R, Shephard JM (2024) Movement of Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) across different agricultural regions in Western Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC23015.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1974a) Subspeciation in the White-tailed Black Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus baudinii, in Western Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 1, 55-69.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1974b) The occurrence of the White-tailed Black Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus baudinii, in Pinus plantations in Western Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 1, 45-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1980) Food and movements of the short-billed form of the White-tailed Black Cockatoo. Australian Wildlife Research 7, 257-269.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1982) The breeding behaviour and biology of the short-billed form of the White-tailed Black Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus. Ibis 124, 422-455.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1986) Breeding-season, nesting success and nestling growth in Carnabys Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus-funereus-latirostris, over 16 years at Coomallo Creek, and a method for assessing the viability of populations in other areas. Australian Wildlife Research 13, 261-273.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1988) Patagial tags – do benefits outweigh risks to the animal? Australian Wildlife Research 15, 565-569.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (1990) Problems of survival in an extensively cultivated landscape: the case of Carnaby’s cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus latirostris. Biological Conservation 54, 277-290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R (2009) Update on longevity and movements of Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo. Pacific Conservation Biology 15, 72-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R (2018) Cumulative learnings and conservation implications of a long-term study of the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Australian Zoologist 39(4), 591-609.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Ingram JA (1987) Factors affecting survival of breeding populations of Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus latirostris in remnants of native vegetation. In ‘Nature conservation: the role of remnants of native vegetation’. (Eds DA Saunders, GW Arnold, AA Burbidge, ALM Hopkins) pp. 249–258. (Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Ltd: Chipping Norton, NSW)

Saunders DA, Ingram JA (1998) Twenty-eight years of monitoring a breeding population of Carnaby’s Cockatoo. Pacific Conservation Biology 4, 261-270.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Pickup G (2023) A review of the taxonomy and distribution of Australia’s endemic Calyptorhynchinae black cockatoos. Australian Zoologist 43, 145-191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R, Mawson P (2011) Photographic identification of bands confirms age of breeding Carnaby’s Black Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Corella 35, 52-54.

| Google Scholar |

Saunders D, Dawson R, Doley A, Lauri J, Le Souëf A, Mawson P, Warren K, White N (2014a) Nature conservation on agricultural land: a case study of the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris breeding at Koobabbie in the northern wheatbelt of Western Australia. Nature Conservation 9, 19-43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Mawson PR, Dawson R (2014b) One fledgling or two in the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus latirostris): a strategy for survival or legacy from a bygone era? Conservation Physiology 2, cou001.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Mawson PR, Dawson R (2014c) Use of tree hollows by Carnaby’s Cockatoo and the fate of large hollow-bearing trees at Coomallo Creek, Western Australia 1969–2013. Biological Conservation 177, 185-193.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, White NE, Dawson R, Mawson PRM (2018) Breeding site fidelity, and breeding pair infidelity in the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Nature Conservation 27, 59-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R, Mawson PR, Cunningham RB (2020a) Artificial hollows provide an effective short-term solution to the loss of natural nesting hollows for Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Biological Conservation 245, 108556.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R, Mawson PR, Nicholls AO (2020b) Factors affecting nestling condition and timing of egg-laying in the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Pacific Conservation Biology 26, 22-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R, Mawson PR (2023) Artificial nesting hollows for the conservation of Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris: definitely not a case of erect and forget. Pacific Conservation Biology 29, 119-129.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stock WD, Finn H, Parker J, Dods K (2013) Pine as a fast food: foraging ecology of an endangered cockatoo in a forestry landscape. PLoS ONE 8, e61145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Valentine LE, Fisher R, Wilson BA, Sonneman T, Stock WD, Fleming PA, Hobbs RJ (2014) Time since fire influences food resources for an endangered species, Carnaby’s Cockatoo, in a fire-prone landscape. Biological Conservation 175, 1-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

White NE, Bunce M, Mawson PR, Dawson R, Saunders DA, Allentot ME (2014) Identifying conservation units after large-scale land clearing: a spatio-temporal molecular survey of endangered white-tailed black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus spp.). Diversity and Distributions 20, 1208-1220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |