Aboriginal-constructed lizard traps on Western Australia’s south coast create reptile habitat and teach principles of granite outcrop conservation

Susie Cramp A * , Lynette Knapp A B , Harriet Paterson A , Peter Speldewinde A , Alison Lullfitz A and Stephen D. Hopper

A * , Lynette Knapp A B , Harriet Paterson A , Peter Speldewinde A , Alison Lullfitz A and Stephen D. Hopper  A

A

A

B

Abstract

Granite outcrops of the Southwest Australian Floristic Region are places of cultural and ecological significance that are at risk from human disturbance. Lizard traps are propped-up rock slabs on granite outcrops, constructed by Aboriginal peoples to create habitat for and to catch reptiles. Despite the cultural importance of traps, public awareness remains low, and they are at risk from destruction and removal. Lizard traps are likely ecologically important, but data supporting this have yet to be published.

We aimed to; (1) clarify the ecological role of lizard traps on Western Australia’s south coast; (2) address the hypothesis that lizard traps provide reptile habitat; and (3) explore what lizard traps teach us about conservation of granites.

Directed by Merningar Elder Lynette Knapp, and focused around Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, we used time-lapse cameras to undertake a cross-cultural investigation into the ecological role of lizard traps.

We found at least seven reptile groups use lizard traps on Western Australia’s south coast for activities including thermoregulation and shelter. Reptile presence was observed at 60% of lizard traps over 1 day. We found no difference between natural exfoliation (known reptile habitat) and lizard traps in reptile occurrence, diversity, duration of presence, and thermal complexity. Elder Lynette Knapp shares that lizard traps were created for human survival, and they teach us that caring for granite Country involves minimising disturbance, deep knowledge of the landscape, and multi-generational thinking.

First Nations-constructed lizard traps create reptile habitat as a key principle of caring for granite Country.

Lizard traps are culturally and ecologically important features of granite outcrops that need greater recognition and protection.

Keywords: Australian Aboriginal Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), caring for country, conservation, granite outcrops, human niche construction, lizard traps, Merningar/Menang, reptiles, Southwest Australian Floristic Region.

Introduction

‘Caring for Country’ is a First Nations concept that outlines the responsibility and right to look after the land of ones’ people, using knowledge that has been passed down through families since time immemorial; ‘If you care for Country, Country cares for you’ (Woodward and McTaggart 2019; Taylor-Bragge et al. 2021). Despite the many barriers between people, Country, and culture created by colonisation, caring for Country practices are ongoing (Land and Alliance 2020; Brown and Thompson 2020; Taylor-Bragge et al. 2021; Fatima et al. 2023; Larson et al. 2023). For co-author Merningar Elder Lynette Knapp (LK; she/her), caring for Country is ‘inbuilt, like breathing’. Practices have changed over time with the contemporary technology and economic systems providing novel tools, incentives, and constraints (Brown and Thompson 2020; Land and Alliance 2020). Research into caring for Country today is ongoing and increasing, but requires learning how to strengthen and develop practices (Ens et al. 2015; Ens and Turpin 2022).

Aboriginal peoples represent 3.2% of Australia’s population (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021) and therefore, caring for Country often involves cross-cultural collaborations. Cross-cultural conservation is growing rapidly and understanding of how to undertake research ‘right-way’ is becoming more established. ‘Right-way’ science is based on trust, respect, open-mindedness, and mutual learning with research questions directed by Aboriginal Elders, and carried out with Aboriginal peoples, rather than for them or on them. Indigenous ways of knowing are prioritised, rather than making them fit into the dominant colonial settler worldview (AIATSIS 2020; Johnston and Forrest 2020; Land and Alliance 2020; Smith 2021; Hird et al. 2023). Cross-cultural collaborations give deep insights that are not possible with purely western scientific frameworks. For example, Elder feedback on plant harvest style allowed greater understanding of regeneration of tubers (Lullfitz et al. 2021), and Aboriginal art depicting termites helped to solve an international debate on the cause of ‘fairy circles’, which are bare circles of hardened earth found among spinifex (Walsh et al. 2023). As each cross-cultural collaboration becomes more established, it is important to continuously reflect on its trajectory (Daniels et al. 2022); it may begin with consultation, then progress with direction from Elders. This can pave the way to younger Aboriginal peoples becoming researchers themselves and, as this evolves, ongoing reflection aids understanding of how to carry out cross-cultural conservation in ways that are increasingly socially, ecologically, and culturally sustainable and beneficial.

This paper is a cross-cultural collaboration arising from a recognised need to better care for granite Country on Western Australia’s south coast, identified during a decade of collaborative research. LK holds knowledge of granites passed down through her family since time immemorial (Knapp et al. 2011, 2024; Cramp et al. 2022). Steve Hopper (SDH) has studied granite flora for over 40 years, developing a corpus of work outlining new theories of their ecology and evolution – the OCBIL theory (Hopper 2009, 2018, 2023; Hopper et al. 2016). Co-authors have noticed declining natural and cultural heritage of granite outcrops, with minimal actions being taken to stop degradation.

Granite outcrops are ecologically and culturally significant, and at risk from human disturbance (Porembski et al. 2016; Michael and Lindenmayer 2018; Migoń 2021). In Australia, granite underlies much of its south-western corner, has a scattered distribution in the centre, and forms a belt running down the eastern coast (Geoscience Australia 2012). Granites are like islands, providing refuge from fire and climatic extremes, and different habitat compositions to surrounding landscapes (Michael and Lindenmayer 2018; Hopper 2023). They are ancient, stable environments that provide consistent micro-climates and niches over the timescale of millennia (Twidale 1982; Couper and Hoskin 2008; Hopper 2009; Fitzsimons and Michael 2017). Following the principles of OCBIL theory, these attributes of granites have led to increased levels of endemic, specialised, and threatened species with characteristics of being long-lived, vulnerable to disturbance, and resilient to isolation (Hopper 2009, 2018, 2023; Hopper et al. 2016). Threats faced by Australian granites include recreational activities, mining, invasive species, inappropriate fire regimes, and climate change. Suggested management actions include minimising human disturbance, fencing and baiting to reduce the impact of feral herbivores and predators, education, and cross-cultural collaborations (Porembski et al. 2016; Michael and Lindenmayer 2018; Cramp et al. 2022; Hopper 2023). However, more quantitative data on threats to granite outcrops, their ecological and cultural impacts, and effective conservation actions are required.

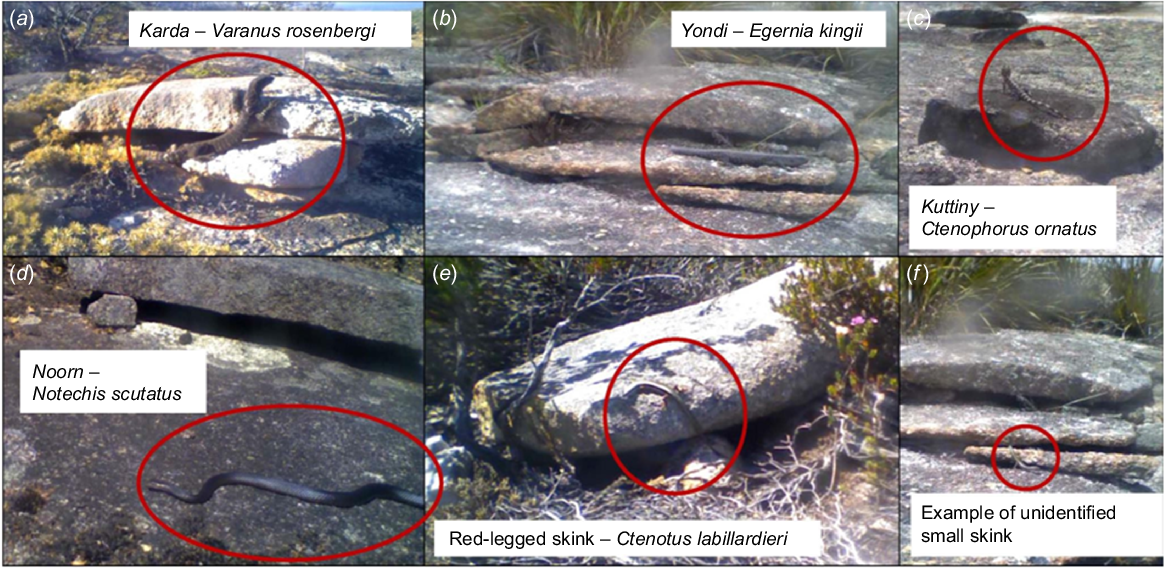

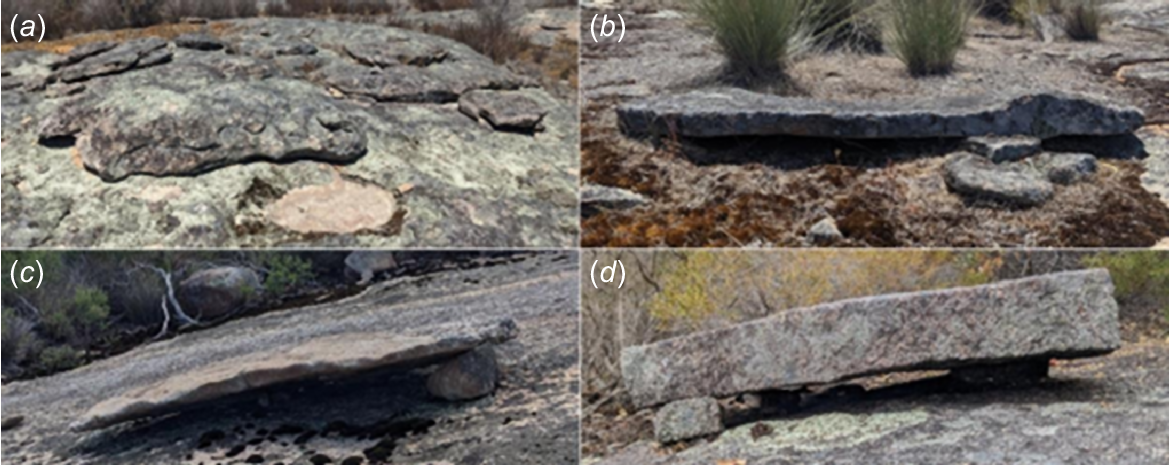

Lizard traps are one practice involved in caring for granite Country. Lizard traps are propped-up rock slabs created by Aboriginal peoples to provide habitat for and catch reptiles (Fig. 1; Cramp et al. 2022). They are common and widespread on undisturbed granite outcrops of south-west Australia, and recently have been discovered in New South Wales and south-east Queensland in places such as Girraween National Park (Cramp et al. 2022; S. D. Hopper, unpubl. data). They hold great cultural significance, by creating a connection through time to the ancestor that created them (Cramp et al. 2022). Elders share that they also play an important ecological role by providing areas for reptiles to bask and retreat into shade, protection from aerial predators, and places to forage for smaller reptiles and insects (Cramp et al. 2022). They are currently being lost due to removal and destruction. Possibly unaware of their natural and cultural significance, people remove slabs for garden landscaping, pile them up into cairns, or drive over them. Despite much speculation in the limited literature (Cramp et al. 2022), understanding of the ecological role of lizard traps remains unclear (Guislain et al. 2020).

Examples of lizard traps. (a, b) Fitzgerald River National Park. (c) Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. (d) West Cape Howe National Park (photographs: Susie Cramp).

Natural exfoliation has been well established as important reptile habitat because loose surface rocks increase thermal and habitat complexity (Michael et al. 2010; Cogger 2018) and provide opportunities for thermoregulation, shelter, and food (Michael et al. 2010). Because reptiles are ectotherms, thermal conditions are key determinants of their behaviour and distribution (Huey et al. 1989; Dittmer et al. 2020). Rocky habitats create thermal refuges, allowing persistence of species during extreme climatic events (Dittmer et al. 2020; García et al. 2020). Such refuges will likely become increasingly important with climate change (Selwood and Zimmer 2020). The protective influence of rocky outcrops during changing climates has led to the persistence of rainforest lineages in ancient rocky niches (Couper and Hoskin 2008). Thus, protecting rocky niches can protect many species. Niche specialists are more vulnerable to human disturbances, particularly when their niche relies upon non-renewable lithic resources, such as natural exfoliation (Michael et al. 2015). Whether lizard traps are playing a similar ecological role to natural exfoliation has yet to be tested. Given their cultural significance, answering this question using ‘right-way’ science principles is crucial. Furthermore, learning more about the function and ecology of lizard traps will teach us more about how to care for granite Country.

Our team of Merningar Elder LK and western conservation scientists (SC, HP, AL, PS, and SDH) has undertaken a cross-cultural investigation into the previously unclear ecological role of lizard traps on Western Australia’s south coast. We address the hypothesis that lizard traps provide reptile habitat and explore what lizard traps teach us about conservation of granites. With limited published data and public awareness, lizard traps face many uncontrolled threats. We aim to increase ecological understanding of lizard traps and add weight to their protection.

Materials and methods

Cross-cultural collaboration

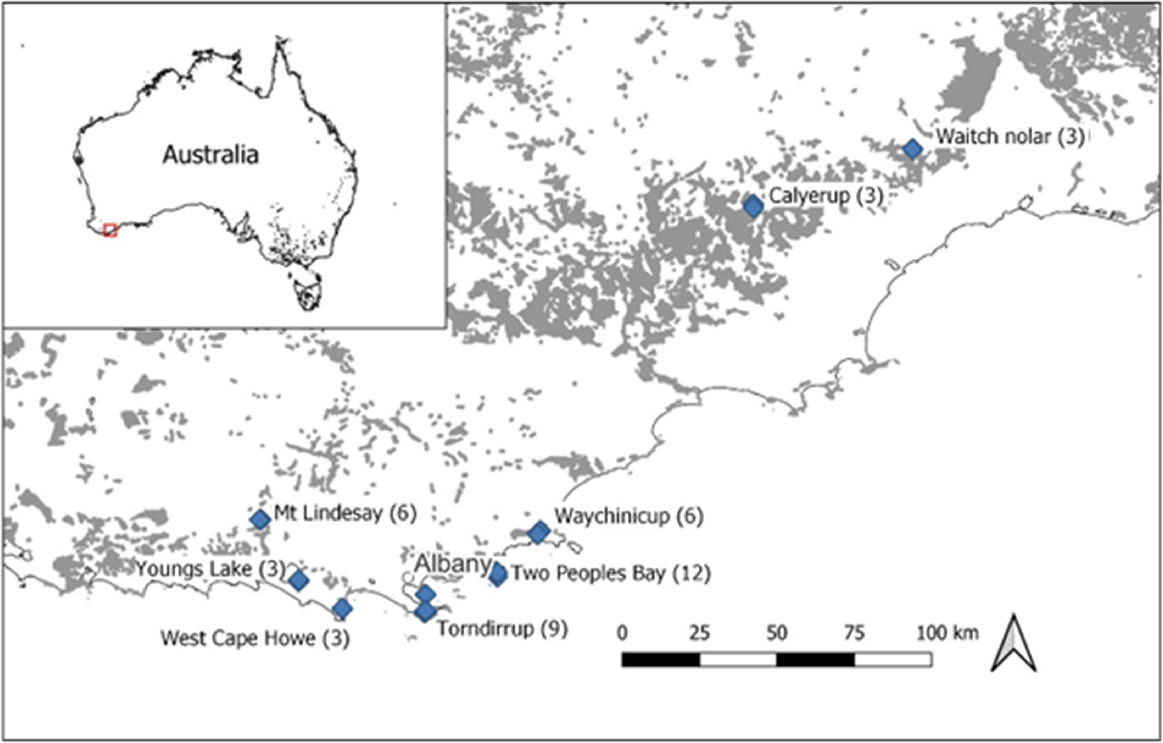

Directed by Merningar Elder LK and informed by a global literature review of lizard traps (Cramp et al. 2022), this study seeks to determine whether lizard traps provide reptile habitat, and share their associated cultural implications. To understand their role in the landscape and to ensure cultural protocols were followed, close cross-cultural collaboration has been maintained throughout the research. SC and LK selected sites together to ensure it was culturally appropriate to deploy cameras in these areas, and if special considerations were required. All sites were on Merningar/Menang/Goreng Country, including Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Fig. 2). Once data had been collected and analysed, results were discussed with LK, whose perspectives were recorded.

Map of locations where time-lapse cameras were deployed. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of granite outcrops in that location. Grey shading indicates granite surface bedrock (Geoscience Australia 2012). Research was based in Kinjarling/Albany, Merningar/Menang Country.

Data collection methodology

Reptile taxa and behaviour at lizard traps, natural exfoliation, and bare granite were recorded using Brinno TLC200 time-lapse cameras. Habitats were classed as: (1) lizard traps (i.e. propped-up rock slab of 50–150 cm in diameter/width); (2) natural exfoliation (i.e. un-propped rock slab chosen to be roughly the same size as a lizard trap); and (3) bare granite. We followed a pilot study where thermal cameras and time-lapse imagery were used simultaneously at the same location; the former were not reliably triggered by reptiles that were observed by the latter (SC, unpubl. data).

Cameras were deployed at 45 granite outcrops with the most (n, 12) located at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Fig. 2). At each granite outcrop, there were three camera sites comprising a lizard trap, a natural exfoliation,and a bare granite site, resulting in a total of 135 camera sites. The 45 granite outcrops were distributed between eight areas across Merningar Country between December 2022 and April 2023 (Fig. 2). Granite outcrops were in nature reserves (Two Peoples Bay), national parks (Waitch Nolar, Waychinicup, Torndirrup, West Cape Howe, and Mt Lindesay), unallocated Crown land (Calyerup), and private property (Youngs Lake). To minimise the risk of camera theft and reduce influence of human presence on reptile behaviour, areas frequently used by the public were avoided.

To compare reptile activity between the three habitat types, camera sites at the same granite site were situated within 10 m of each other. Cameras were deployed for between 5 and 10 days and took one photograph every 1 s. To ensure cameras were observing the same size area, cameras were placed 1 m away from the habitat they were monitoring, and on a stand 40 cm off the ground. During the study period, cameras were deployed at three sites simultaneously per week. Granite outcrops were a minimum of 100 m apart that included a minimum of 20 m of vegetation separating each granite outcrop.

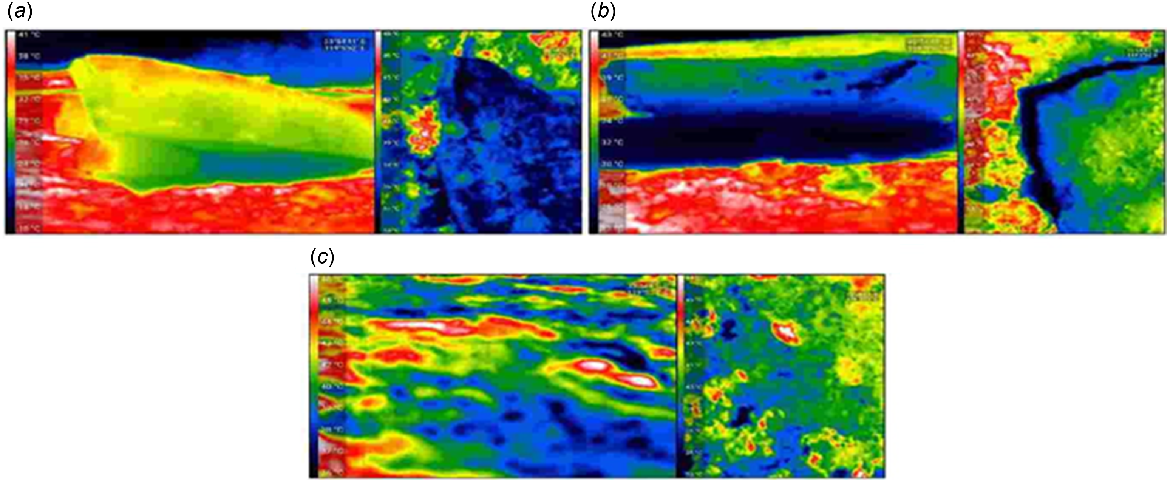

A thermal camera (Seek CompactPRO XR) was used to photograph the plan and oblique view of each habitat at each granite site (Fig. 3). The plan view photograph was taken facing directly down from chest height of co-author SC (130 cm). The oblique view photograph was taken from ground level 50 cm from the habitat. Thermal images provided thermal data for a single point in time for each habitat at each site. Timing of photographs was also recorded.

Pairs of thermal images of different habitats on granite outcrops from oblique (left) and plan (right) view. (a) Lizard trap; (b) natural exfoliation; (c) bare granite. Each photograph has a scale bar on the left-hand side indicating temperature in degrees Celsius, with hottest being red/white and coldest blue/black. Located at Calyerup 2.

Data processing

To establish reptile diversity, occurrence, and behaviour at the three habitat types, a day of time-lapse footage from each camera at each site was analysed. The second day of deployment at each site was selected, to ensure influence from human presence during camera set up and collection was standardised, and to maximise the number of sites with available days of footage. With increasing number of deployment days there was a greater chance of failure due to cameras falling over, batteries running out, SD cards filling up, or random camera failure. All reptile activity on Day 2 time-lapse footage was recorded, including the time each reptile appeared and left, behaviour, species (where possible), and the weather during that time. Camera failure occurred nine times. Footage was analysed from 42 lizard trap, 41 natural exfoliation, and 43 bare granite sites. Due to inadequate image resolution, small skinks were identified only to family level. To calculate thermal range of habitats at a single point in time, the highest and lowest temperature in each thermal photo was recorded.

Data analysis

R studio 4.2.0 (R Studio Team 2022), and R packages ‘lubridate’ (Grolemund and Wickham 2011), ‘dplyr’ (Wickham et al. 2023), ‘hms’ (Muller 2022), and ‘tidyverse’ (Wickham et al. 2019) were used for data analysis. Summary statistics were performed using base R. To test if species occurring at lizard traps, natural exfoliation, and bare granite were different, the correlation between habitat and number of sites for each observed species was tested using Pearson’s correlation. To test if there was a significant difference between lizard traps, natural exfoliation, and bare granite in number of reptile occurrences, duration of reptile visits in seconds, number of reptile species, and thermal range in degrees centigrade, Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed, comparing those metrics between habitats at the same site.

Results

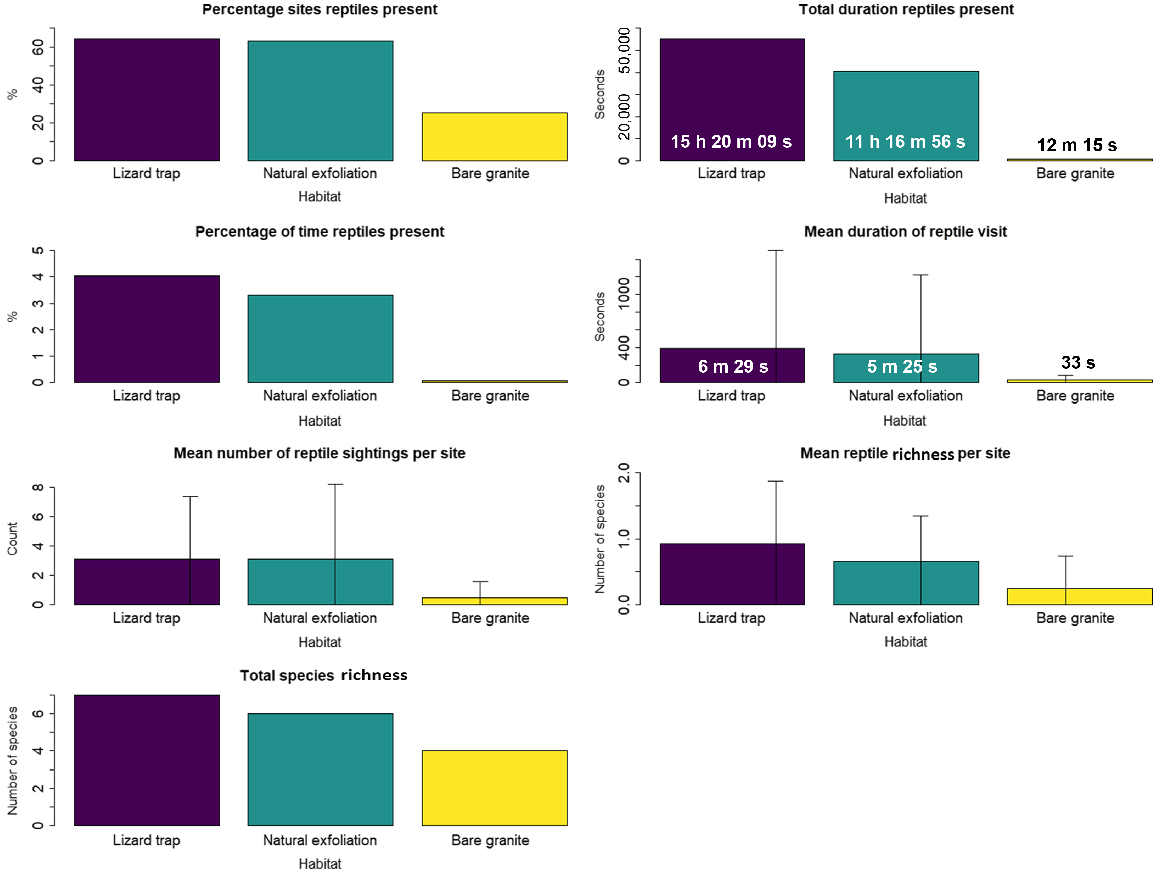

Reptiles are commonly observed at lizard traps

Time-lapse cameras deployed on granite outcrops showed that reptiles are commonly observed at lizard traps. A total of 27 of 42 lizard trap sites had reptiles present within 1 day of footage, with a total reptile presence of over 15 h, and reptiles observed at lizard traps 4% of the time. Reptile activity was similar between lizard traps and natural exfoliation. Total duration of reptile presence was slightly greater at lizard traps than at natural exfoliation. Reptile activity was much lower at bare granite than lizard traps and natural exfoliation (Fig. 4).

Overview of reptile presence at lizard traps (purple), natural exfoliation (green), and bare granite (yellow). Black line bars indicate standard deviation. Data from Day 2 only.

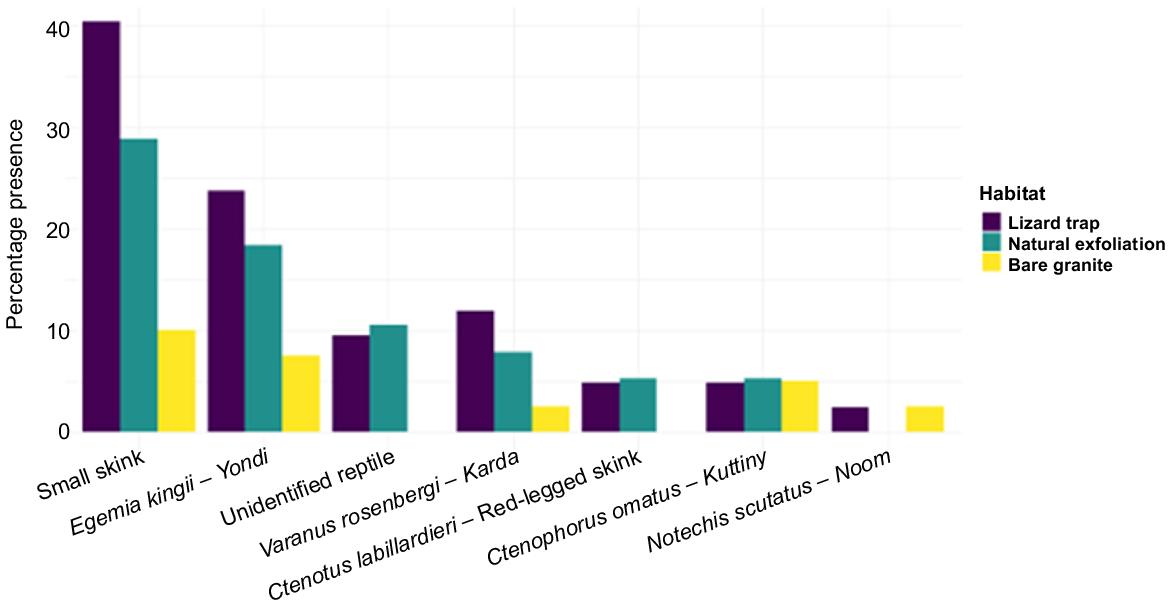

At least five species were observed at lizard traps: Varanus rosenbergi, Egernia kingii, Ctenophorus ornatus, Notechis scutatus, and Ctenotus labillardieri (Figs 4–6) along with the unidentified reptile and small skinks categories. Only two areas (Calyerup and Waitch Nolar) were within the range of C. ornatus.

There is no difference between reptile occurrence at lizard traps and natural exfoliation

Analysis of reptile occurrence, presence, diversity, and thermal range showed no difference between lizard traps and natural exfoliation. There was a significant difference between lizard traps and bare granite, and natural exfoliation and bare granite (Table 1).

| Comparison | Number of reptile occurrences | Duration of reptile presence (s) | Number of reptile species | Thermal range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | P-value | W | P-value | W | P-value | W | P-value | ||

| LT vs NE | 125 | 0.70 | 211 | 0.90 | 161.5 | 0.10 | 1328.5 | 0.47 | |

| LT vs BG | 279 | <0.001 | 355 | <0.001 | 298 | <0.001 | 2841.5 | <0.001 | |

| NE vs BG | 244 | <0.001 | 263 | <0.001 | 202.5 | <0.005 | 2980 | <0.001 | |

W, Wilcoxon signed ranking test statistic; LT, lizard trap; NE, natural exfoliation; BG, bare granite.

Small skinks and E. kingii were the most observed reptiles at lizard traps and natural exfoliation (Fig. 6). A similarity index of presence (% sites that species where present; Fig. 6) at lizard traps, natural exfoliation, and bare granite showed no difference between lizard traps and natural exfoliation in observed reptile assemblages (Pearson’s correlation of lizard trap against natural exfoliation = 0.99, lizard trap against bare granite = 0.83, natural exfoliation against bare granite = 0.78).

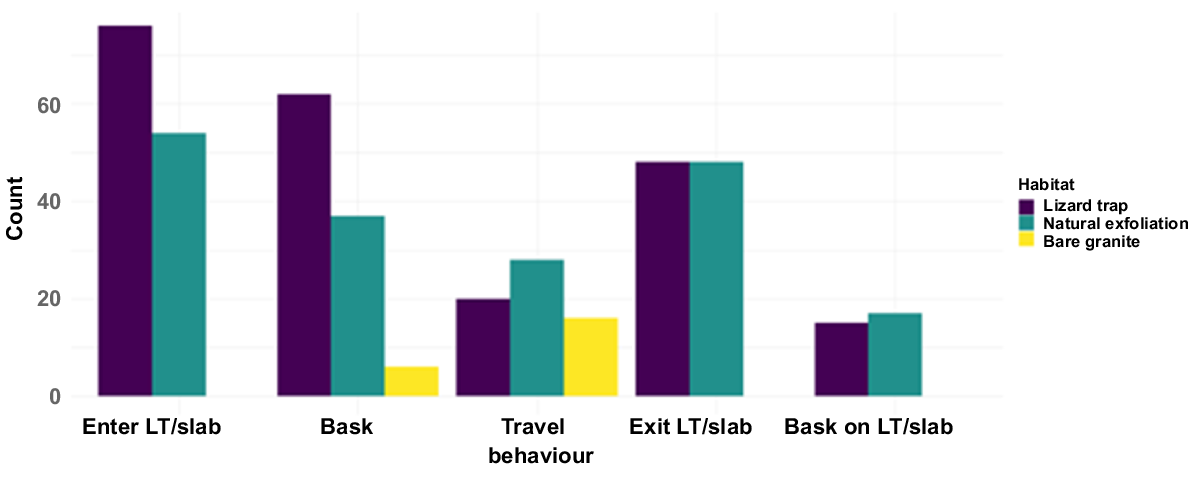

Reptiles use lizard traps for thermoregulation and shelter

Reptiles were observed in time-lapse photographs basking on, near, and entering and exiting lizard traps. There were more occurrences of reptiles entering lizard traps than exiting. There were more observations of basking at lizard traps than at natural exfoliation (Fig. 7).

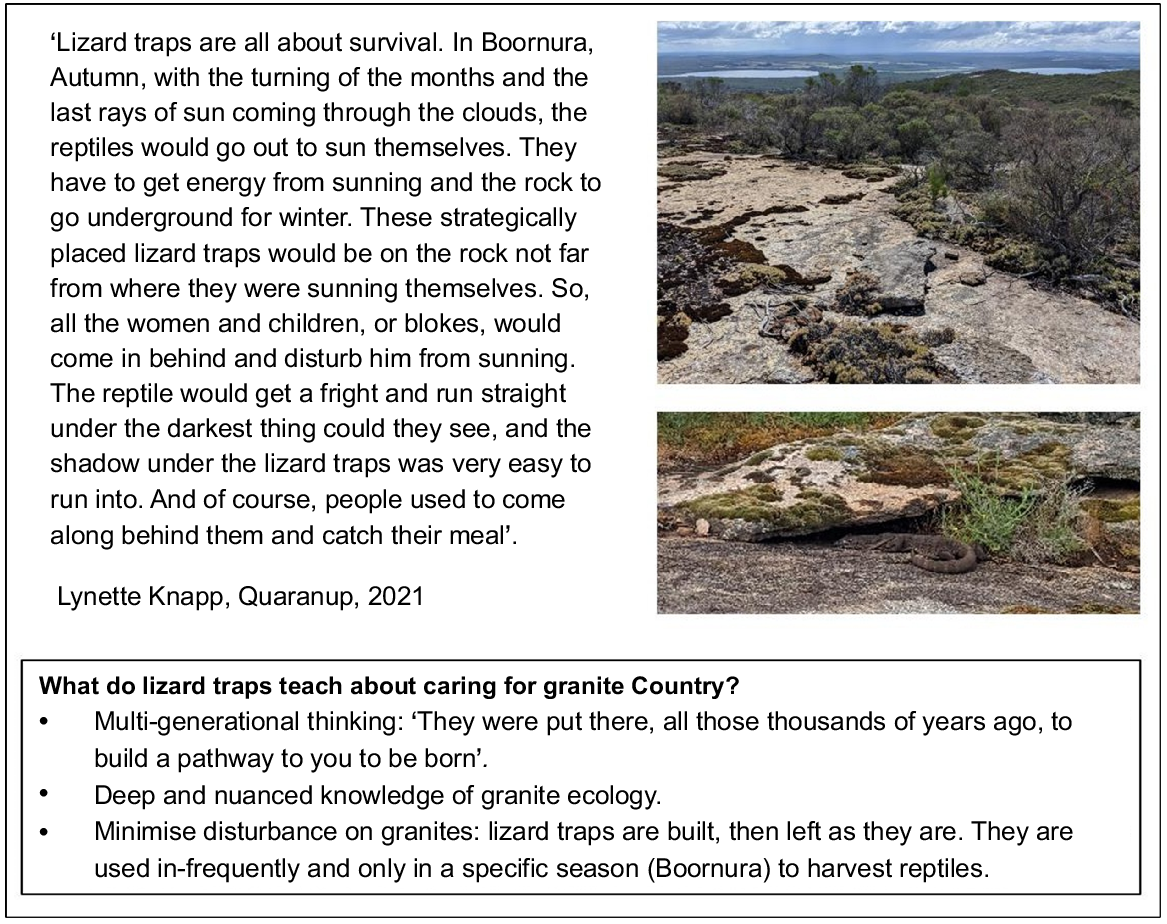

Learning from lizard traps about caring for granite country

LK shares that reptiles use lizard traps because they must bask in Boornura [Autumn] to obtain enough energy to hibernate over winter. Lizard traps offer suitable retreat sites to bask near because if they are disturbed by predators during this vulnerable activity, they can quickly and easily find safety (unless that predator is a human). For the Knapp family, constructing and maintaining lizard traps is about survival as they provide a reliable food source in Boornura [Autumn] (Fig. 8). LK’s recollections align with data collected for this study showing that reptiles use lizard traps for basking near, or on, and for going underneath (Fig. 7). Karda (V. rosenbergi) are the most sought-after reptile that use lizard traps, followed by Wargyl (Morelia spilota), Yoorn (bobtails, Tiliqua rugosa), Noorn (N. scutatus), and Dubitch (dugites, Pseudonaja affinis). Yondi (E. kingii) commonly use lizard traps but are only eaten if people are very hungry. Kuttiny (C. ornatus) use lizard traps, and LK has fond memories of chasing these as a child, and her children doing the same. Kuttiny (C. ornatus) were never eaten and there were repercussions from the Elders if caught harming them. Many other smaller reptiles use lizard traps, such as geckoes and frogs; these were not eaten, but recognised as food sources for larger reptiles. Birds of prey, while using thermals from granite outcrops to gain altitude, hunt basking reptiles off the rocks. Lizard traps also provide refuge for reptiles from aerial predators.

Discussion

Rock crevice use by saxicolous reptiles has been thoroughly investigated (Croak et al. 2008, 2010; Michael et al. 2008; Croak 2012), but until now construction of lizard traps by Aboriginal peoples has been overlooked. Here, we present the first substantial ecological information indicating that lizard traps provide habitat for reptiles, highlighting their importance as both culturally and ecologically significant features.

These data confirm that lizard traps create habitat for reptiles, finding significant reptile presence and diversity at lizard traps, and observing that reptiles use them for thermoregulation and shelter. Here, scientific findings are corroborated by continuous oral history from LK, who highlights that lizard traps provide a dark crevice for reptiles to retreat beneath when disturbed during basking. We show that lizard traps are important cultural and ecological features that need to be protected.

Lizard traps provide habitat for reptiles

Time-lapse camera photography has given important insights into reptile activity at lizard traps, revealing novel data on reptile occurrence, species, and behaviours exhibited. Previous publications often mentioned observations of reptiles using lizard traps (Cramp et al. 2022), and Guislain et al. (2020) carried out inconclusive thermally triggered camera studies investigating lizard traps as reptile habitat. Importantly, these data are unsurprising to LK, with Traditional ecological knowledge previously shared by Merningar and Menang Elders that included all the species and behaviours observed in this study (Cramp et al. 2022). Further species and behaviours are outlined in traditional ecological knowledge, including pythons (Morelia spilota), dugites (P. affinis), and bobtails (T. rugosa) using lizard traps to evade aerial predators, and forage. Co-authors have also observed additional species using lizard traps that included M. spilota (Waargyl [carpet python]) retreating beneath a lizard trap on a warm winters’ day, Egernia napoleonis (crevice skink) using a lizard trap to ambush flying insects, two observations of P. affinis (Dubitch [dugite]) basking near lizard traps before retreating down a small hole (presumably their burrow) next to the lizard trap, and Elapognathus coronatus (crown snake) using a lizard trap as a midway shelter whilst travelling across a granite outcrop (SC and SDH, unpubl. observations).

Identification of small skinks to genus or species level would further outline the biota supported by lizard traps, such as Christinus marmoratus (marbled gecko) and Underwoodisaurus milii (barking gecko) (Cogger 2018). However, this would be culturally and ecologically disruptive as investigation into detailed species identity typically requires lifting rocks; Government guidelines for survey of threatened reptiles state that this practice is destructive to habitats and the species that use them. Turning rocks is still an accepted technique (Australian Government 2011), but we suggest finding alternative survey methods to minimise destructive impact on both environmental and cultural grounds.

There is no difference between lizard traps and natural exfoliation

Lizard traps can provide shelter for much larger reptiles than natural exfoliation, such as the desired food species Karda (V. rosenbergiFig. 8) when propped up about 10–20 cm. We saw slightly more Karda activity at lizard traps than natural exfoliation (present at 12% compared to 8% of sites respectively), but further investigation is required to understand if lizard traps facilitate Karda occupancy and if this species prefers lizard traps over natural exfoliation (Guislain et al. 2020).

Reptiles use lizard traps for thermoregulation and shelter

Thermal data aids understanding as to why reptiles are using lizard traps. Lizard traps significantly increase thermal complexity compared to bare granite. That gives reptiles greater control over their thermoregulation, which is a key part of surviving and reproducing (Thierry et al. 2009; Lelièvre et al. 2010). Reptiles need to maintain a body temperature between 20°C and 30°C and this is primarily done through poikilothermy, aided by behaviours of basking, adjusting posture, and finding favourable microclimates (Dawson 1975). On hot days, the surface of bare granite was over 40°C, while lizard traps varied from 22°C to 64°C and provided a cool space to generally maintain optimum body temperatures. In the context of a warming climate, this indicates the potential importance of lizard traps as thermal refuges (Huey et al. 1989; Selwood and Zimmer 2020). Here, we documented the range of temperature provided by lizard traps and recommend further study on thermal complexity over time of day, weather, and different seasons to elucidate when and why reptiles are using lizard traps, and how they add to the thermoregulatory environment of granites.

Learning from lizard traps about caring for granite Country

Lizard traps teach us that caring for granites involves long-term (multi-generational) thinking, minimising disturbance, and deep understanding of ecosystems. Lizard traps are rock formations that are initially constructed, possibly thousands of years ago (Smith 1993), in very precise locations chosen for their thermo-regulatory properties and proximity to reptile activity (LK, pers. comm.). Traps are subtle structures, and to the untrained eye may appear like a natural rock. Although not commonly used today, pre-colonisation they were used to catch reptiles as people moved through their tracts of lands along the coast (Robertson et al. 2021). Lizard traps were only used in Boornura [Autumn] before the rains arrived and reptiles were sunning themselves ready to go underground for winter (LK, pers. comm.). This meant most of the year lizard traps were undisturbed by people.

Merningar ways of interacting with granites are very different to contemporary use. Today granite outcrops are mined, used for water storage, damaged by vehicles, while loose surface rocks are stacked and removed (including lizard traps) and moss mat vegetation communities are disturbed (Porembski et al. 2016; Michael and Lindenmayer 2018; Cramp et al. 2022). For Merningar Custodians, granite outcrops are places of learning, spirituality, and reverence, where you tread lightly and minimise your impact (Knapp et al. 2011; Cramp et al. 2022).

Bringing together traditional ecological knowledge and novel scientific techniques can be powerful in understanding and caring for Country (Ens et al. 2012; Walsh et al. 2013; Ens and Turpin 2022). This seems particularly relevant to granites, where the Aboriginal peoples and colonial settler worldviews have opposite ways of interacting with these ancient hotspots of biodiversity and cultural values.

Conclusion

We show definitively that lizard traps provide habitat for reptiles at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and elsewhere on the south coast of Western Australia. Lizard traps teach us that caring for granite Country involves minimising disturbance, appreciating the deep and nuanced knowledge of the landscape and multi-generational thinking. We highlight that lizard traps are both culturally and ecologically important and require much greater levels of protection.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article and accompanying online supplementary material.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by the Northcote Trust PhD scholarship (SC), a private donation via the Blackwell family, and the Walking Together Project. The Walking Together Project 2020–2024 was a partnership between University of Western Australia and South Coast Natural Resource Management, supported by Lotterywest, UWA’s Research Priority Fund, and a startup grant from Janet Holmes à Court.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Merningar/Menang/Goreng boodjar, where we live and work, and the Elders past, present, and emerging who have cared for and continue to care for the land, air, and waters. We are particularly grateful to the Knapp family for their generous sharing of Merningar knowledge. We thank the many volunteers who assisted with deployment of cameras and to the landowners whose property cameras were installed on. The research involving human data was assessed and approved by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval #: HREA RA/4/20/6165. The research involving animal data was assessed and approved by The University of Western Australia Animal Ethics Committee. Approval #: Observational Studies Approval F18979. We acknowledge SC’s PhD examiners Jack Pascoe and Chelsea Geralda Armstrong who provided in-depth feedback on this manuscript, and the Guest Editor of the The Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia collection Denis Saunders, reviewer Ric How, and a further anonymous reviewer for their time, consideration, and assistance.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021) Australian population data, snapshot of Australia. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/snapshot-australia/latest-release [accessed 16 October 2023]

Australian Government (2011) Survey guidelines for Australia’s threatened reptiles. Available at https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/epbc/publications/survey-guidelines-australias-threatened-reptiles [accessed 12 November 2023]

Brown SM, Thompson S (2020) Gracevale, a case study on caring for country and rediscovery of culture and language by the Iningai people in central west Queensland. The Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland 128, 23-27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Couper PJ, Hoskin CJ (2008) Litho-refugia: the importance of rock landscapes for the long-term persistence of Australian rainforest fauna. Australian Zoologist 34(4), 554-560.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cramp S, Murray S, Knapp L, Coyne H, Eades A, Lullfitz A, Speldewinde P, Hopper SD (2022) Overview and investigation of Australian Aboriginal lizard traps. Journal of Ethnobiology 42(4), 400-416.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Croak BM, Pike DA, Webb JK, Shine R (2008) Three-dimensional crevice structure affects retreat site selection by reptiles. Animal Behaviour 76(6), 1875-1884.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Croak BM, Pike DA, Webb JK, Shine R (2010) Using artificial rocks to restore nonrenewable shelter sites in human-degraded systems: colonization by fauna. Restoration Ecology 18(4), 428-438.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Daniels CW, Russell S, Ens EJ, Ngukurr Yangbala rangers (2022) Empowering young Aboriginal women to care for country: case study of the Ngukurr Yangbala rangers, remote northern Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 53-63.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dittmer DE, Chapman TL, Bidwell JR (2020) In the shadow of an iconic inselberg: uluru’s shadow influences climates and reptile assemblage structure at its base. Journal of Arid Environments 181, 104179.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Turpin G (2022) Synthesis of Australian cross-cultural ecology featuring a decade of annual Indigenous ecological knowledge symposia at the ecological society of Australia conferences. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 3-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Finlayson M, Preuss K, Jackson S, Holcombe S (2012) Australian approaches for managing ‘country’ using Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge. Ecological Management & Restoration 13(1), 100-107.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Pert P, Clarke PA, Budden M, Clubb L, Doran B, Douras C, Gaikwad J, Gott B, Leonard S, Locke J, Packer J, Turpin G, Wason S (2015) Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: review and insight from Australia. Biological Conservation 181, 133-149.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fatima Y, Liu Y, Cleary A, Dean J, Smith V, King S, Solomon S (2023) Connecting the health of country with the health of people: application of “caring for country” in improving the social and emotional well-being of Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific 31, 100648.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fitzsimons JA, Michael DR (2017) Rocky outcrops: a hard road in the conservation of critical habitats. Biological Conservation 211, 36-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

García MB, Domingo D, Pizarro M, Font X, Gómez D, Ehrlén J (2020) Rocky habitats as microclimatic refuges for biodiversity. A close-up thermal approach. Environmental and Experimental Botany 170, 103886.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Grolemund G, Wickham H (2011) Dates and times made easy with lubridate. Journal of Statistical Software 40(3), 1-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Guislain L, Knapp L, Lullfitz A, Speldewinde P (2020) Are Karda (Varanus rosenbergii) more abundant around traditional Noongar lizard traps? Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 103, 43-47.

| Google Scholar |

Hird C, David-Chavez DM, Gion SS, van Uitregt V (2023) Moving beyond ontological (worldview) supremacy: Indigenous insights and a recovery guide for settler-colonial scientists. Journal of Experimental Biology 226(12), jeb245302.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hopper SD (2009) OCBIL theory: towards an integrated understanding of the evolution, ecology and conservation of biodiversity on old, climatically buffered, infertile landscapes. Plant and Soil 322, 49-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hopper SD (2018) Natural hybridization in the context of Ocbil theory. South African Journal of Botany 118, 284-289.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hopper SD (2023) Ocbil theory as a potential unifying framework for investigating narrow endemism in mediterranean climate regions. Plants 12(3), 645.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hopper SD, Silveira FAO, Fiedler PL (2016) Biodiversity hotspots and Ocbil theory. Plant and Soil 403, 167-216.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Huey RB, Peterson CR, Arnold SJ, Porter WP (1989) Hot rocks and not-so-hot rocks: retreat-site selection by garter snakes and its thermal consequences. Ecology 70(4), 931-944.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Knapp L, Cummings D, Cummings S, Fiedler PL, Hopper SD (2024) A Merningar Bardok family’s Noongar oral history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and surrounds. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24018.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Larson S, Jarvis D, Stoeckl N, Barrowei R, Coleman B, Groves D, Hunter J, Lee M, Markham M, Larson A, Finau G, Douglas M (2023) Piecemeal stewardship activities miss numerous social and environmental benefits associated with culturally appropriate ways of caring for country. Journal of Environmental Management 326, 116750.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lelièvre H, Blouin-Demers G, Bonnet X, Lourdais O (2010) Thermal benefits of artificial shelters in snakes: a radiotelemetric study of two sympatric colubrids. Journal of Thermal Biology 35(7), 324-331.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lullfitz A, Pettersen C, Reynolds R, Eades A, Dean A, Knapp L, Woods E, Woods T, Eades E, Yorkshire-Selby G, Woods S, Dorth J, Guilfoyle D, Hopper SD (2021) The Noongar of south-western Australia: a case study of long-term biodiversity conservation in a matrix of old and young landscapes. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 133(2), 432-448.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michael DR, Cunningham R, Lindenmayer D (2008) A forgotten habitat? Granite inselbergs conserve reptile diversity in fragmented agricultural landscapes. Journal of Applied Ecology 45(6), 1742-1752.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michael DR, Cunningham RB, Lindenmayer DB (2010) The social elite: habitat heterogeneity, complexity and quality in granite inselbergs influence patterns of aggregation in Egernia striolata (Lygosominae: Scincidae). Austral Ecology 35(8), 862-870.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michael DR, Kay GM, Crane M, Florance D, Macgregor C, Okada S, McBurney L, Blair D, Lindenmayer DB (2015) Ecological niche breadth and microhabitat guild structure in temperate Australian reptiles: implications for natural resource management in endangered grassy woodland ecosystems. Austral Ecology 40(6), 651-660.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Migoń P (2021) Granite landscapes, geodiversity and geoheritage – global context. Heritage 4(1), 198-219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Muller K (2022) hms: pretty time of day. R Package Version 1.1.2. Available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=hms

Porembski S, Silveira FAO, Fiedler PL, Watve A, Rabarimanarivo M, Kouame F, Hopper SD (2016) Worldwide destruction of inselbergs and related rock outcrops threatens a unique ecosystem. Biodiversity and Conservation 25, 2827-2830.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

R Studio Team (2022) RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. Available at http://www.rstudio.com/

Selwood KE, Zimmer HC (2020) Refuges for biodiversity conservation: a review of the evidence. Biological Conservation 245, 108502.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Taylor-Bragge RL, Whyman T, Jobson L (2021) People needs Country: the symbiotic effects of landcare and wellbeing for Aboriginal peoples and their countries. Australian Psychologist 56(6), 458-471.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thierry A, Lettink M, Besson AA, Cree A (2009) Thermal properties of artificial refuges and their implications for retreat-site selection in lizards. Applied Herpetology 6, 307-326.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Walsh FJ, Dobson PV, Douglas JC (2013) Anpernirrentye: a framework for enhanced application of indigenous ecological knowledge in natural resource management. Ecology & Society 18,.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Walsh F, Bidu GK, Bidu NK, Evans TA, Judson TM, Kendrick P, Michaels AN, Moore D, Nelson M, Oldham C, Schofield J, Sparrow A, Taylor MK, Taylor DP, Wayne LN, Williams CM, Taylor K, Taylor N, Williams W, Simpson MR, Robinson M, Judson J, Oates D, Biljabu J, Biljabu D, Peterson P, Robinson N, Mac Gardener K, Edwards T, Williams R, Rogers R, Gibbs D, Chapman N, Nyaju R, James JJ (2023) First Peoples’ knowledge leads scientists to reveal ‘fairy circles’ and termite linyji are linked in Australia. Nature Ecology & Evolution 7(4), 610-622.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, Francois R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen TL, Miller E, Bache SM, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel DP, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H (2019) Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 4(43), 1686.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wickham H, Francois R, Henry L, Muller K, Vaughan D (2023) A grammar of data manipulation. R Package Version 1.1.2. Available at https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.dplyr [accessed 15 January 2024]

Woodward E, McTaggart PM (2019) Co-developing Indigenous seasonal calendars to support ‘healthy Country, healthy people’ outcomes. Global Health Promotion 26(3), 26-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |