Open data for biogeography research of the genus Metrosideros across the south-central Pacific region

Thomas R. Etherington A B * , Murray I. Dawson A , Anne Sutherland C and James K. McCarthy

A B * , Murray I. Dawson A , Anne Sutherland C and James K. McCarthy  A

A

A

B

C

Abstract

Mapping the distribution of species from the genus Metrosideros is crucial for developing surveillance and management plans associated with species conservation in response to issues such as rapid ‘ōhi‘a death spread in the south-central Pacific region.

To support this endeavour, we recognised there was a need for open and reliable geographic information system data on island locations, extents, and occurrence data of Metrosideros species.

Using an open science framework, we reviewed six sources of island data and five sources of species occurrence data for availability, accuracy, and licencing criteria.

OpenStreetMap emerged as the optimal island location data, offering accuracy, precision, and open licencing, with this data improved and reprojected for mapping purposes. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility provided the majority of Metrosideros species occurrence data, but analysis of occurrence data from iNaturalist revealed common mis-identifications with regional biases that were corrected prior to compilation. The occurrence data of Metrosideros species was also supplemented by vegetation plot data, with HAVPlot and sPlotOpen providing key additional data for some species and islands.

Citizen science data via iNaturalist and OpenStreetMap formed the core of the compiled datasets. While such crowdsourced data can have quality issues, with additional crowdsourced curatorial effort these datasets will be significant and scalable sources of data into the future.

All compiled occurrence and GIS data are made openly available via permissive data licences to better support future biogeographical research in the south-central Pacific region.

Keywords: Ceratocystis huliohia, Ceratocystis lukuohia, citizen science, GIS data, mapping, Myrtaceae, occurrence data, rapid ‘ōhi‘a death.

Introduction

The south-central Pacific region, defined here as the combination of the islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia, covers a vast proportion of the planet. The south-central Pacific region has distinct biophysical characteristics with high levels of endemism, including almost all species of the widespread genus Metrosideros (Myrtaceae) (Wright et al. 2021). The genus was thought to have originated in New Zealand, but based on earlier conclusive fossils may have originated in Tasmania in the Oligo-Miocene where it is now extinct (Tarran et al. 2016, 2017). From Australia, it may have dispersed across the Pacific through New Zealand and New Guinea where it is the major component of many Indigenous island floras. One such example is Metrosideros polymorpha (‘ōhi‘a lehua), which is dominant across many Hawai‘ian ecosystems (Mueller-Dombois and Fosberg 1998) where it is a key component of plant communities of all ages (Mueller-Dombois 1992). Unfortunately, this species is highly susceptible to rapid ‘ōhi‘a death (ROD), a disease caused by two recently introduced Ceratocystis fungal pathogens, Ceratocystis huliohia and Ceratocystis lukuohia. The origins of these species are unclear but they reside in Asia-Australian and Latin American Ceratocystis clades, respectively (Barnes et al. 2018). Many species in the genus are also susceptible to myrtle rust (caused by Austropuccinia psidii), another invasive fungal pathogen native to South America (Coutinho et al. 1998). Information on the distributions of susceptible species is critical for management of these diseases. For example, distributions of endemic Metrosideros across New Zealand have been used to inform the management response to myrtle rust (McCarthy et al. 2021). At present, ROD is only known from Hawai‘i, but there is a risk it may spread across susceptible Metrosideros in the Pacific. Given evidence that other Metrosideros species such as Metrosideros excelsa from New Zealand could also be susceptible to ROD (Luiz et al. 2022), information about the pan-Pacific distributions of Metrosideros species is critical for developing surveillance and management plans that could prevent wider impacts from potential ROD spread across the Pacific region.

Geographic information system (GIS) data on the locations of islands within the south-central Pacific region is of critical foundational importance for mapping plant distributions, as islands represent the ultimate limit of distributional extent of terrestrial species such as those in the genus Metrosideros. Unfortunately, the south-central Pacific region is cartographically disadvantaged as the convention of using the Greenwich Meridian as a default prime meridian results in some Pacific islands being artificially split. Also, there are numerous small islands within the south-central Pacific region, meaning that automated mapping from satellite imagery can be technically difficult, and creating the potential for differences in mapping scale to have pronounced effects on the inclusion or exclusion of small islands by different data creators. Therefore, appropriate GIS island location data needs to be created to support any mapping exercise in the south-central Pacific region.

For species occurrence data, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org) system for aggregating worldwide biodiversity databases (Edwards et al. 2000) has become the de facto source of open access species occurrence data for biogeographical analyses. While GBIF aggregates occurrence data from a wide range of providers, there are other potential sources of data that should be considered. This is important as many Pacific nations and Metrosideros species are not well represented by GBIF data (GBIF 2024). Therefore, while GBIF provides an excellent starting point, we are conscious that there are other potentially important sources of open access occurrence data such as those from initiatives like the sPlotOpen project (Sabatini et al. 2021) that could inform a clearer picture of Metrosideros distributions in the south-central Pacific region. Investing effort in integrating these various open access datasets would provide a useful resource from which other projects that require occurrence records can be developed. In this regard, our focus on open access data is of critical importance such that the resulting data sources can be widely used.

Therefore, our objective was to create two open data products: (1) GIS data for the outlines of islands in the south-central Pacific region with relevant attribute information and in a suitable map projection with improved geometries; and (2) occurrence data of Metrosideros species compiled from several sources with unified and consistent taxonomy. Our hope is that creating this data within an open science framework will enable the broader research community to advance knowledge about Metrosideros distributions in support of issues such as those currently created by pathogenic fungi including Ceratocystis.

Materials and methods

Pacific islands GIS data

Our approach to building GIS data on the locations of islands within the south-central Pacific region was to review a series of potential sources of data. Our two key criteria were to find GIS data that: (1) provided polygons of Pacific islands with accuracy and precision at around the 1:50,000 map scale; and (2) were openly licenced in a manner that would allow for redistribution and modification. We identified several potential sources of data for our review that included Natural Earth (Natural Earth 2023), Global Self-consistent Hierarchical High-resolution Geography (Wessel and Smith 1996), Global Shoreline Vector (Sayre et al. 2019), GADM database of global administrative areas (GADM 2023), Pacific island region spatial data (South Pacific Regional Environment Programme 2022), and OpenSteetMap (OpenStreetMap contributors 2023).

We also applied data quality checks for topology to ensure the resulting GIS data was of a high standard, and updated the polygons to account for any within island borders and added attribute information to classify the geo-administrative units. Given the extent of the island data, the Projection Wizard tool (Šavrič et al. 2016) identified the Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection (centred at: 12.11°S, 169.15°W) as the most appropriate map projection. Therefore, we also reprojected the data from the global WGS84 geographic coordinate system to this projected coordinate system using the ‘sf’ R package (Pebesma 2018), and then combined island polygons of Fiji that had been split across the prime anti-meridian (±180° longitude) associated with the WGS84 geographic coordinate system.

Occurrence data

Plant location data are primarily sourced as occurrence data, mostly from herbarium records, citizen science tools, regional flora texts, or from vegetation plots which also describe plant absences and co-occurrences and usually some measure of abundance. We reviewed and sourced all global occurrence data from these sources for 54 of 58 Metrosideros species (Table 1) that are accepted to occur within the south-central Pacific region (Wright et al. 2021; Royal Botanic Gardens Kew 2024).

| Species | Authority | Expected locations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metrosideros albiflora | Sol. ex Gaertn. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros arfakensis | Gibbs | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros bartlettii | J.W.Dawson | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros brevistylis | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros cacuminum | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros carminea | W.R.B.Oliv. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros cherrieri | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros colensoi | Hook.f. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros collina | (J.R.Forst. & G.Forst.) A.Gray | Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Pitcairn Islands, Society Islands, Tuamotu, Tubuai Islands | |

| Metrosideros cordata | (C.T.White & W.D.Francis) J.W.Dawson | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros diffusa | (G.Forst.) Sm. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros dolichandra | Schltr. ex Guillaumin | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros elegans | (Montrouz.) Beauvis. | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros engleriana | Schltr. | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros excelsa | Sol. ex Gaertn. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros fulgens | Sol. ex Gaertn. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros gregoryi | Christoph. | Samoa | |

| Metrosideros humboldtiana | Guillaumin | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros kermadecensis | W.R.B.Oliv. | Kermadec Islands (New Zealand) | |

| Metrosideros laurifolia | Brongn. & Gris | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros longipetiolata | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros macropus | Hook. & Arn. | Hawai‘i | |

| Metrosideros microphylla | (Schltr.) J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros nervulosa | C.Moore & F.Muell. | Lord Howe Island | |

| Metrosideros nitida | Brongn. & Gris | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros ochrantha | A.C.Sm. | Fiji | |

| Metrosideros operculata | Labill. | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros oreomyrtus | Däniker | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros ovata | (C.T.White) J.W.Dawson | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros paniensis | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros parallelinervis | C.T.White | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros parkinsonii | Buchanan | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros patens | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros perforata | (J.R.Forst. & G.Forst.) A.Rich. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros polymorpha | Gaudich. | Hawai‘i | |

| Metrosideros porphyrea | Schltr. | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros punctata | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros ramiflora | Lauterb. | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros regelii | F.Muell. | New Guinea | |

| Metrosideros robusta | A.Cunn. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros rotundifolia | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros rugosa | A.Gray | Hawai‘i | |

| Metrosideros salomonensis | C.T.White | Solomon Islands | |

| Metrosideros sclerocarpa | J.W.Dawson | Lord Howe Island | |

| Metrosideros tabwemasanaensis | Pillon | Vanuatu | |

| Metrosideros tardiflora | (J.W.Dawson) Pillon | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros tetragyna | J.W.Dawson | Solomon Islands | |

| Metrosideros tetrasticha | Guillaumin | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros tremuloides | (A.Heller) Rock | Hawai‘i | |

| Metrosideros umbellata | Cav. | New Zealand | |

| Metrosideros vitiensis | (A.Gray) Pillon | Fiji, Samoa, Vanuatu | |

| Metrosideros waialealae | (Rock) Rock | Hawai‘i | |

| Metrosideros whitakeri | J.W.Dawson | New Caledonia | |

| Metrosideros whiteana | J.W.Dawson | New Guinea |

Within GBIF’s Oceania region, the vast majority of Metrosideros occurrences since the year 2000 have come from the iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/) crowdsourced species identification and occurrence recording platform (GBIF 2024). We are fully supportive of such efforts, but we are also conscious that crowdsourced data can have quality issues such as mis-identifications and mis-scoring of cultivated individuals as wild (López-Guillén et al. 2024). Therefore, we anticipated that reviewing and correcting the available iNaturalist data would be an important task ahead of downloading data from GBIF to ensure the data downloaded was as accurate as possible. A worldwide data quality review was undertaken, primarily to correct mis-identifications and to help ensure the correct scoring of wild versus cultivated status of purported Metrosideros observations uploaded by contributors to the iNaturalist platform. This was achieved by conducting global, country, and custom boundary searches for Metrosideros as a taxon, then switching to grid view to spot likely errors based on the thumbnail cover images and location. Links to individual observations were then followed, with taxonomic identifications either corrected or confirmed, updates to whether the individual was wild or cultivated, annotations of plant phenology scored (flower budding/flowering/fruiting), and comments added as appropriate.

With iNaturalist observations updated and corrected, we downloaded occurrence data for our 54 Metrosideros species (Table 1) from GBIF (GBIF.org 2024) via the ‘rgbif’ R package (Chamberlain and Boettiger 2017) in April 2024.

Since GBIF is primarily a repository for occurrence records, vegetation plot data are not frequently housed in the facility. There are some exceptions; for example, species observations from openly available plot data in the New Zealand National Vegetation Survey Databank (NVS; Wiser et al. 2001) are uploaded to GBIF as occurrence records. Therefore, we chose not to rely solely on GBIF data and instead supplemented occurrence data from GBIF with plot data from openly available sources. These included the Botanical Information and Ecology Network (BIEN; Enquist et al. 2016), accessed via the ‘BIEN’ R package (Maitner et al. 2018), the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program collected by the US Department of Agriculture (Burrill et al. 2023), the Australian HAVPlot database (Mokany et al. 2022a, 2022b), and sPlotOpen (Sabatini et al. 2021). Downloads from these sources were completed between October 2023 and February 2024.

We anticipated data quality issues within compiled occurrence data that needed to be considered ahead of analysis (Meyer et al. 2016). While each future analysis using our compiled data will likely need to make individual decisions around taxonomic, spatial, and temporal data cleaning dependant on specific methods and goals (Zizka et al. 2020), we believed there were some actions that would be universally relevant and therefore could be undertaken now to create efficiencies in reusing the compiled data and to give a truer picture of the availability of Metrosideros occurrence data. We removed any Metrosideros occurrences where the exact species was not specified and did not have a known year of observation. We also ensured that all species names conformed to the accepted nomenclature (Table 1). Given the importance of precise and accurate locations for distribution mapping requirements (Marcer et al. 2022), we also removed occurrences with an unspecified location uncertainty, a specified location uncertainty greater than 10 km, or that were further than 10 km from our Pacific island GIS data. A threshold of 10 km was chosen as coordinates for sensitive occurrence data is commonly generalised to 0.1° (≈ 10 km) precision within GBIF and for the purposes of mapping pan-Pacific distributions this level of precision was considered acceptable for purposes such as species range mapping. For each species we also removed any occurrences that duplicated the same coordinate in the same year.

Results

Pacific islands GIS data

An obvious and immediate finding was that polygons from the Natural Earth data (Natural Earth 2023), while public domain and with good attribute data, were at too coarse a resolution to provide island extents at the precision required for localised mapping. The Global Self-consistent Hierarchical High-resolution Geography (Wessel and Smith 1996), while available under a Lesser GNU Public Licence, had no attribute information and we detected issues with both the accuracy and precision of the polygons. The Global Shoreline Vector (Sayre et al. 2019) data contained a lot of potentially useful attribute information such as individual island names, but there were poor quality polygons for some of the atoll islands such as within the Cook Islands. We also had concerns about the licencing as while it was described as public domain, no specific licence was provided. The GADM database of global administrative areas (GADM 2023) uses a bespoke licence that prevents redistribution and hence eliminated it as a useful data source for our needs. The Pacific island region spatial data (South Pacific Regional Environment Programme 2022) had accurate and precise polygons, and was openly licenced under a CC BY-NC-SA licence. However, it lacked attribute information for the polygons and did not include many of the islands we required for our needs, such as those of New Zealand and Hawai‘i. OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap contributors 2023) polygon accuracy and precision was at least equal to the other data sources considered. It also became apparent that the Pacific island region spatial data (South Pacific Regional Environment Programme 2022) appeared to be a derived product of OpenStreetMap given the presence of identical polygons. OpenStreetMap is also clearly licenced under the Open Database License (ODbL) that is very permissive in allowing the data to be used in any context.

From our review, we concluded that OpenStreetMap was the best option given our needs for accurate and precise boundaries provided under a permissive open licence. This created GIS data that is uniquely well suited for mapping across the south-central Pacific region, with 23,421 individual polygons with the associated attribute table classifying each polygon among 31 different island groups. As specified in the terms of the ODbL licence under which OpenStreetMap is provided, our resulting GIS data was also licenced under the ODbL.

Occurrence data

No taxonomic harmonisation was required with all databases providing species names consistent with the accepted nomenclature (Table 1). We found that some species were commonly mis-identified across a wide taxonomic spectrum by either the iNaturalist contributors or the iNaturalist computer vision species identification algorithm (e.g. mis-identification of Melaleuca as Metrosideros polymorpha in California https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/9036079, or as M. excelsa in Portugal https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/82143976). Many of these mis-identifications had regional biases. For example, the related species M. excelsa, Metrosideros kermadecensis, Metrosideros collina, and M. polymorpha were frequently confused in cultivation. Metrosideros polymorpha appears to be very rarely cultivated outside of its native range of Hawai‘i, but was heavily over-reported in cultivation, especially in California where the correct identifications were usually M. excelsa and M. collina. Conversely, M. collina had been heavily under-reported in cultivation in places such as California, Spain, Portugal, New Zealand, and Australia where it had typically been mis-identified as M. excelsa and M. polymorpha.

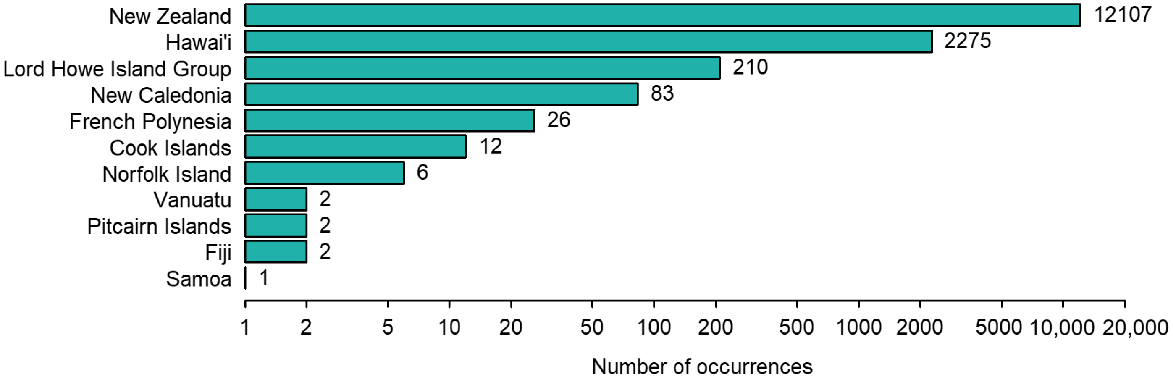

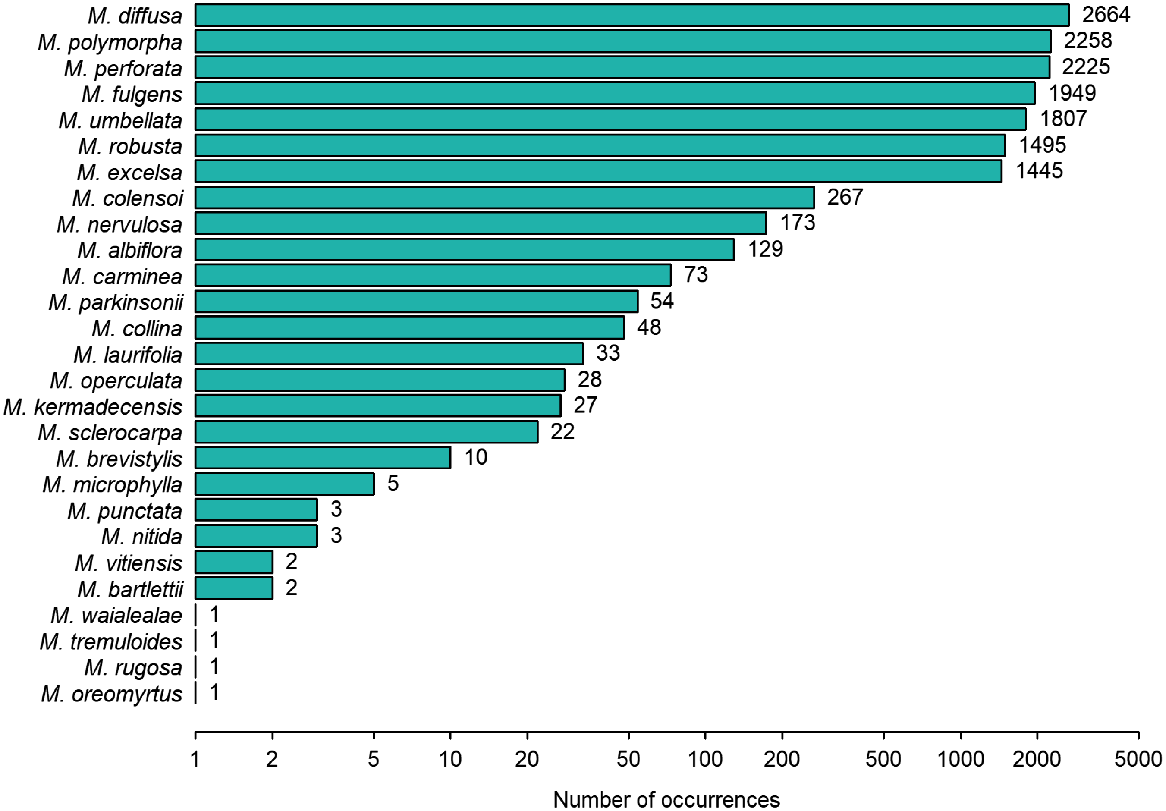

Across all occurrence data sources, 14,726 Metrosideros observations were identified and included in our dataset. However, the taxonomic and geographic distribution of these occurrences was extremely skewed. Only eight island groups had any occurrences, and New Zealand and Hawai‘i alone contributed 98% of the occurrences, with the remaining island groups having few occurrences (Fig. 1), and 23 groups having no occurrences. Similarly, endemic species from New Zealand and Hawai‘i dominated the species occurrences, with only 27 of the targeted 54 Metrosideros species represented in the compiled dataset (Fig. 2).

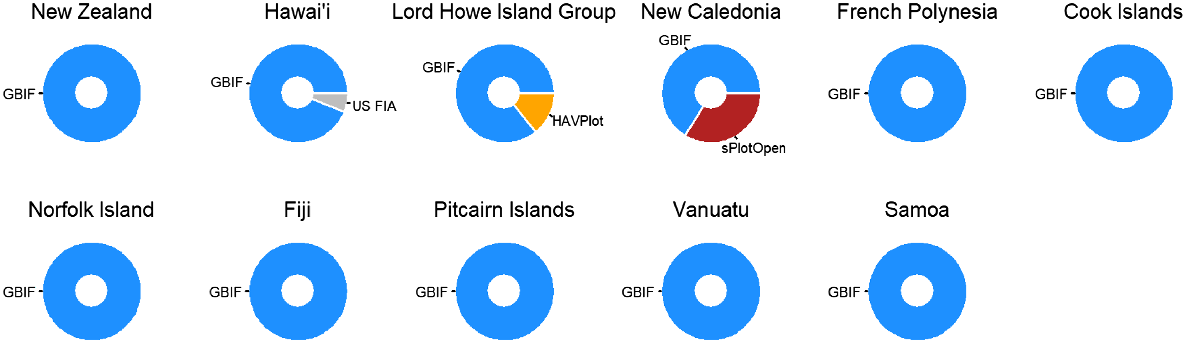

In terms of data sources, 99% of the occurrences came from GBIF. However, when broken down geographically, the additional plot data was concentrated specifically in Hawai‘i, the Lord Howe Island Group, and in New Caledonia. For New Caledonia in particular, the sPlotOpen data provided a good proportion of the available data (Fig. 3). When broken down by species, GBIF data dominates again, but with some species data primary or sole data source coming from HAVPlot and sPlotOpen (Fig. 4).

Regarding BIEN, we found that this dataset would only provide 33 additional occurrences, but without location uncertainty information. As the data was licenced under a CC-BY-NC-ND licence that precludes resharing the data in a modified form, no BIEN data was included in our compiled dataset.

Discussion

Compiling appropriate GIS data of the islands of the south-central Pacific was more challenging than expected as there were an array of options each with varying pros and cons that had to be reviewed. On balance, the use of OpenStreetMap was preferable primarily due to its permissive licencing model. The value of such reliable GIS data was immediately evident as it was used as part of our data cleaning process to identify species occurrences within marine locations in which Metrosideros species should occur.

We were less successful in compiling reliable data on all Metrosideros species’ occurrence. Unfortunately, we discovered that there was extremely limited data availability for some regions and species within GBIF, which is the world’s biggest aggregator of open access occurence data. Some Pacific islands had only tens of occurrences for Metrosideros species known to occur there. Similarly, some Metrosideros species had only tens of occurrences throughout the whole Pacific region. Given the expected distributions of many of these species (Table 1), this highlights a significant gap in some of the openly available Metrosideros occurrence data within the south-central Pacific region, likely in part due to restricted distributions and inaccessibility to rare species. What was interesting to note was how the effort to include additional data from vegetation plot databases proved to be particularly valuable for locations such as the Lord Howe Island Group and New Caledonia (Fig. 3) with some species being solely represented by data from sPlotOpen (Fig. 4). We would therefore recommend that plot data be regularly considered as part of plant occurrence data compilation, as this additional effort can fill gaps in knowledge that would result from relying on GBIF federated data alone.

Data quality is another issue, especially as much of the species occurrence data is originally derived from the iNaturalist citizen science platform. These issues were also addressed in a recent analysis by López-Guillén et al. (2024). We discovered and corrected numerous and widespread species mis-identifications that had achieved ‘research grade’ status, and incorrect reporting of observations as wild rather than their true cultivated status distorts natural distribution patterns. Such errors are problematic in themselves, but mis-identifications have the potential to bias the underlying computer vision species identification algorithms of iNaturalist (iNaturalist 2023), which result in compounding errors and the geographically localised collections of mis-identifications we observed. While we corrected many errors as part of our review of the data, these changes do require a majority of the iNaturalist community to agree with our re-identifications before they can become ‘research grade’ again, and as such we would encourage those interested in developing our knowledge of Metrosideros distributions to become similarly engaged in reviewing iNaturalist data. A strength of the iNaturalist platform is that not only are the species observations uploaded by numerous contributors, but the curatorial components (identifications, annotations etc.) are similarly crowdsourced. To support that effort, we identified some general trends in mis-identification.

Metrosideros kermadecensis has smaller and more rounded leaves than the closely related M. excelsa, but relative leaf size can be difficult to interpret from uploaded images; a more reliable character is the sporadic flowering season of M. kermadecensis throughout most of the year compared to a tight peak flowering period (November–January in the Southern Hemisphere) typical for M. excelsa. Reliable identification of M. kermadecensis in cultivation is complicated by the occurrence of hybrids between M. kermadecensis and M. excelsa, and this combination has only recently been added to the iNaturalist platform.

With more than 40 name cultivars (Dawson and Heenan 2010), M. excelsa is the most cultivated species of the genus worldwide. Its preference for warm-temperate coastal climates exposes mis-identifications in areas not suited to its cultivation, including common mis-identification for Callistemon/Melaleuca in drier inland areas of the USA (e.g. Arizona and Texas). Although in the same family (Myrtaceae) and sharing colourful red flower filaments, the flowers and leaves of Callistemon/Melaleuca (and Corymbia ficifolia, another mis-identification frequently encountered) are easily separable from Metrosideros, most likely illustrating the occurrence of local confirmation bias among observers.

Members of different genera and families, namely several Calliandra (Fabaceae), Combretum (Combretaceae), and Stifftia (Asteraceae) species were also mis-identified as Metrosideros due to a superficial similarity of flowers. Lonicera ligustrina (box-leaved honeysuckle; Caprifoliaceae) was frequently mis-identified in the UK, France, Germany, and elsewhere as one of the New Zealand endemic climbing species of Metrosideros (Metrosideros colensoi, Metrosideros diffusa, Metrosideros fulgens, or Metrosideros perforata) due to similar growth form of stems and leaves. A range of other unrelated plants (e.g. Peperomia rotundifolia, Zanthoxylum beecheyanum, several orchids and ferns) were also occasionally mis-identified as these climbing Metrosideros species. Species from these unrelated genera are well outside of the natural and cultivated range of New Zealand endemic Metrosideros. With varying degrees of certainty, numerous records were found marked as wild when they were actually observations of cultivated plants.

A similar comment around improving data quality can also be made regarding the use of OpenStreetMap data because any errors that are detected by a user of this data can be corrected within OpenStreetMap by anyone, meaning that the research community can again build a data resource that everyone can benefit from. While we have already noted that crowdsourced data can have quality issues (Basiri et al. 2019), the maturity and quality of OpenStreetMap is evident from its use by many mainstream companies (Mooney and Minghini 2017).

We only removed occurrences greater than 10 km from land or that had a locational uncertainty greater than 10 km, so users of our data should consider other potential data issues and remedies (see: Zizka et al. 2020; Sillero and Barbosa 2021). While errors in species observation data can be corrected, another data quality issue is that of temporal and geographical sampling bias. Much of the data is concentrated into more recent time and into certain areas of the Pacific due to differences in survey effort and data mobilisation resources. If ignored, such bias can lead to misleading distributional analyses; therefore, care must be taken to use approaches that are insensitive to the inevitable presence of biased data.

We have also only considered distribution information for naturally occurring Metrosideros species. However, many Metrosideros species, in particular M. excelsa, have undergone selection to produce almost 100 cultivars (Dawson and Heenan 2010). This clearly indicates that the distributions of natural Metrosideros species presented here most likely underpredict true distributions of Metrosideros species as many cultivars are likely to be found in human-dominated environments such as gardens and parks. These localised concentrations of Metrosideros individuals could have implications for issues such as plant pathology surveillance and disease control and should not necessarily be ignored.

Despite these possible future developments, our goal is that by making this Metrosideros distributional information openly available, and by updating the information as new and better occurrence data becomes available, we can meet an immediate and critical need for data that will support the development of pan-Pacific surveillance and management plans for Ceratocystis (and potentially) other potential Metrosideros pathogens.

While more data can be collected or mobilised and errors in existing data can be addressed, urgency related to the possible arrival of the two Ceratocystis pathogens causing ROD requires at least an initial mapping of Metrosideros species across the Pacific region, as spreading across these island chains is one of the possible invasion pathways. Despite the recognised limitations in our occurrence data, our datasets represent the most comprehensive data to support such efforts, and both the GIS and occurrence data described here are made freely available under permissive open licences.

Data availability

Metrosideros occurrence data is available at https://doi.org/10.7931/4gdy-gt76 and the GIS Pacific islands data is available at https://doi.org/10.7931/0re5-5k45.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Science Investment Funding for Crown Research Institutes from the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Science and Innovation Group.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Insu Jo for advice on downloading plot data from international repositories, and Matt Buys and Virginia Merroni for early discussion on this usefulness of this work.

References

Barnes I, Fourie A, Wingfield MJ, Harrington TC, McNew DL, Sugiyama LS, Luiz BC, Heller WP, Keith LM (2018) New Ceratocystis species associated with rapid death of Metrosideros polymorpha in Hawai‘i. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 40, 154-181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Basiri A, Haklay M, Foody G, Mooney P (2019) Crowdsourced geospatial data quality: challenges and future directions. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 33, 1588-1593.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chamberlain SA, Boettiger C (2017) R Python, and Ruby clients for GBIF species occurrence data. PeerJ Preprints 5, e3304v1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coutinho TA, Wingfield MJ, Alfenas AC, Crous PW (1998) Eucalyptus rust: a disease with the potential for serious international implications. Plant Disease 82, 819-825.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dawson M, Heenan P (2010) Checklist of Metrosideros cultivars. New Zealand Garden Journal 13, 24-27.

| Google Scholar |

Edwards JL, Lane MA, Nielsen ES (2000) Interoperability of biodiversity databases: biodiversity information on every desktop. Science 289, 2312-2314.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Enquist BJ, Condit R, Peet RK, Schildhauer M, Thiers BM (2016) Cyberinfrastructure for an integrated botanical information network to investigate the ecological impacts of global climate change on plant biodiversity. PeerJ Preprints 4, e2615v2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

GADM (2023) Database of global administrative areas, version 4.1. Available at https://gadm.org/index.html [accessed 9 November 2023]

GBIF (2024) Occurrences of Metrosideros species in Oceania from 2000-2023. Available at https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?continent=OCEANIA&taxon_key=3185258&year=2000,2023 [accessed 15 April 2024]

GBIF.org (2024) GBIF Occurrence Download. Available at https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.9w6wjg [accessed 6 May 2024]

iNaturalist (2023) Frequently asked questions: computer vision. Available at https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/help#computer-vision [accessed 18 October 2023]

López-Guillén E, Herrera I, Bensid B, Gómez-Bellver C, Ibáñez N, Jiménez-Mejías P, Mairal M, Mena-García L, Nualart N, Utjés-Mascó M, López-Pujol J (2024) Strengths and challenges of using iNaturalist in plant research with focus on data quality. Diversity 16, 42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Luiz B, McNeill MR, Bodley E, Keith LM (2022) Assessing susceptibility of Metrosideros excelsa (pōhutukawa) to the vascular wilt pathogen, Ceratocystis lukuohia, causing Rapid ‘Ōhiʻa death. Australasian Plant Pathology 51, 327-331.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maitner BS, Boyle B, Casler N, Condit R, Donoghue J, II, Durán SM, Guaderrama D, Hinchliff CE, Jørgensen PM, Kraft NJB, McGill B, Merow C, Morueta-Holme N, Peet RK, Sandel B, Schildhauer M, Smith SA, Svenning J, Thiers B, Violle C, Wiser S, Enquist BJ (2018) The bienr package: a tool to access the Botanical Information and Ecology Network (BIEN) database. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9, 373-379.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Marcer A, Chapman AD, Wieczorek JR, Xavier Picó F, Uribe F, Waller J, Ariño AH (2022) Uncertainty matters: ascertaining where specimens in natural history collections come from and its implications for predicting species distributions. Ecography 2022, e06025.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McCarthy JK, Wiser SK, Bellingham PJ, Beresford RM, Campbell RE, Turner R, Richardson SJ (2021) Using spatial models to identify refugia and guide restoration in response to an invasive plant pathogen. Journal of Applied Ecology 58, 192-201.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Meyer C, Weigelt P, Kreft H (2016) Multidimensional biases, gaps and uncertainties in global plant occurrence information. Ecology Letters 19, 992-1006.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mokany K, McCarthy J, Falster D, Gallagher R, Harwood T, Kooyman R, Westoby M (2022a) Harmonised Australian Vegetation Plot dataset (HAVPlot). v4. CSIRO. Data Collection. Available at https://doi.org/10.25919/5cex-4s70

Mokany K, McCarthy JK, Falster DS, Gallagher RV, Harwood TD, Kooyman R, Westoby M (2022b) Patterns and drivers of plant diversity across Australia. Ecography 2022, e06426.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mueller-Dombois D (1992) Distributional dynamics in the Hawaiian vegetation. Pacific Science 46, 221-231.

| Google Scholar |

Natural Earth (2023) Admin 0 – Countries, version 5.1.1. Available at https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-cultural-vectors/10m-admin-0-countries/ [accessed 5 July 2023]

OpenStreetMap contributors (2023) OpenStreetMap. Available at https://www.openstreetmap.org [accessed 7 September 2023]

Pebesma E (2018) Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. The R Journal 10, 439-446.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (2024) Plants of the World Online: Metrosideros. Available at https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:331768-2 [accessed 15th April 2024]

Sabatini FM, Lenoir J, Hattab T, Arnst EA, Chytrý M, Dengler J, De Ruffray P, Hennekens SM, Jandt U, Jansen F, Jiménez-Alfaro B, Kattge J, Levesley A, Pillar VD, Purschke O, Sandel B, Sultana F, Aavik T, Aćić S, Acosta ATR, Agrillo E, Alvarez M, Apostolova I, Arfin Khan MAS, Arroyo L, Attorre F, Aubin I, Banerjee A, Bauters M, Bergeron Y, Bergmeier E, Biurrun I, Bjorkman AD, Bonari G, Bondareva V, Brunet J, Čarni A, Casella L, Cayuela L, Černý T, Chepinoga V, Csiky J, Ćušterevska R, De Bie E, de Gasper AL, De Sanctis M, Dimopoulos P, Dolezal J, Dziuba T, El-Sheikh MAE-RM, Enquist B, Ewald J, Fazayeli F, Field R, Finckh M, Gachet S, Galán-de-Mera A, Garbolino E, Gholizadeh H, Giorgis M, Golub V, Alsos IG, Grytnes J-A, Guerin GR, Gutiérrez AG, Haider S, Hatim MZ, Hérault B, Hinojos Mendoza G, Hölzel N, Homeier J, Hubau W, Indreica A, Janssen JAM, Jedrzejek B, Jentsch A, Jürgens N, Kącki Z, Kapfer J, Karger DN, Kavgacı A, Kearsley E, Kessler M, Khanina L, Killeen T, Korolyuk A, Kreft H, Kühl HS, Kuzemko A, Landucci F, Lengyel A, Lens F, Lingner DV, Liu H, Lysenko T, Mahecha MD, Marcenò C, Martynenko V, Moeslund JE, Mendoza AM, et al. (2021) sPlotOpen – An environmentally balanced, open-access, global dataset of vegetation plots. Global Ecology and Biogeography 30, 1740-1764.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Šavrič B, Jenny B, Jenny H (2016) Projection Wizard – an online map projection selection tool. The Cartographic Journal 53, 177-185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sayre R, Noble S, Hamann S, Smith R, Wright D, Breyer S, Butler K, Van Graafeiland K, Frye C, Karagulle D, Hopkins D, Stephens D, Kelly K, Basher Z, Burton D, Cress J, Atkins K, Van Sistine DP, Friesen B, Allee R, Allen T, Aniello P, Asaad I, Costello MJ, Goodin K, Harris P, Kavanaugh M, Lillis H, Manca E, Muller-Karger F, Nyberg B, Parsons R, Saarinen J, Steiner J, Reed A (2019) A new 30 meter resolution global shoreline vector and associated global islands database for the development of standardized ecological coastal units. Journal of Operational Oceanography 12, S47-S56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sillero N, Barbosa AM (2021) Common mistakes in ecological niche models. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 35, 213-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (2022) Pacific island region spatial data. Available at https://pacific-data.sprep.org/dataset/pacific-island-region-spatial-data [accessed 26 September 2023]

Tarran M, Wilson PG, Hill RS (2016) Oldest record of Metrosideros (Myrtaceae): Fossil flowers, fruits, and leaves from Australia. American Journal of Botany 103, 754-768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tarran M, Wilson PG, Macphail MK, Jordan GJ, Hill RS (2017) Two fossil species of Metrosideros (Myrtaceae) from the Oligo-Miocene Golden Fleece locality in Tasmania, Australia. American Journal of Botany 104, 891-904.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wessel P, Smith WHF (1996) A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 101, 8741-8743.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wiser SK, Bellingham PJ, Burrows LE (2001) Managing biodiversity information: development of New Zealand’s National Vegetation Survey databank. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 25, 1-17.

| Google Scholar |

Wright SD, Liddell LG, Lacap-Bugler DC, Gillman LN (2021) Metrosideros (Myrtaceae) in Oceania: origin, evolution and dispersal. Austral Ecology 46, 1211-1220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zizka A, Antunes Carvalho F, Calvente A, Rocio Baez-Lizarazo M, Cabral A, Coelho JFR, Colli-Silva M, Fantinati MR, Fernandes MF, Ferreira-Araújo T, Gondim Lambert Moreira F, Santos NMC, Santos TAB, dos Santos-Costa RC, Serrano FC, Alves da Silva AP, de Souza Soares A, Cavalcante de Souza PG, Calisto Tomaz E, Vale VF, Vieira TL, Antonelli A (2020) No one-size-fits-all solution to clean GBIF. Peerj 8, e9916.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |