Longevity in Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) Carnaby, 1948

Denis A. Saunders A , Peter R. Mawson

A , Peter R. Mawson  B * and Rick Dawson B

B * and Rick Dawson B

A Retired,

B

Abstract

Carnaby’s Cockatoo Zanda latirostris is an endangered species endemic to south-western Australia. It has been the subject of long-term studies of its ecology from 1969 to the present.

This paper examines the maximum recorded life of the species in the wild.

The life spans of eight wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos that were more than 20 years old were compared with longevity records of long-lived birds recorded on the banding registers in Australia, USA, and UK.

Eight wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos were recorded living from 21 to 35 years, putting the species in the top 2% of all bird species in the wild for which there are longevity records.

The longevity of Carnaby’s Cockatoo is similar to that of long-lived seabirds.

Several years of immaturity and low reproductive output mean that Carnaby’s Cockatoos must be long-lived for the species to be sustainable. Conservation actions need to minimise threats to the lives of adult cockatoos.

Keywords: Carnaby’s Cockatoo longevity, conservation, endangered species, longevity of birds, Zanda latirostris.

Introduction

Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) Carnaby, 1948 (family Cacatuidae) is a large (660 g), black bird, with a distinctive white sub-terminal tail band, endemic to south-western Australia (Saunders and Pickup 2023). It is classified as endangered by the Western Australian and Australian governments, as well as internationally (Saunders et al. 2021). Since European settlement, the species has lost much of its breeding and foraging habitat due to extensive clearing of native vegetation, primarily for agricultural development and urbanisation (Saunders et al. 1985). Sexes are the same size, but adult males have a black bill and a small dirty-white/pale-yellow cheek patch, while adult females have bone-coloured bills and large clear-white/pale-yellow cheek patches (Fig. 1). As they reach sexual maturity at three or four years of age (Saunders 1982; Dawson et al. 2013), the birds form pair bonds that last the life of one of the partners (Saunders 1982). In this paper, we examine the maximum recorded life span of Carnaby’s Cockatoo and compare that recorded life span with what is known of other long-lived bird species in the wild.

Pair of Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Zanda latirostris). Left, adult male; right, adult female (photograph Rick Dawson).

In examining the effects of potential land-use change on Carnaby’s Cockatoos, Williams et al. (2017) concluded that adult mortality has a profound effect on population viability; accordingly, it is necessary to understand longevity. Recently, DA Saunders, PR Mawson and R Dawson (unpubl. data) examined adult survival and lifetime reproductive success. In order to replace themselves and maintain a viable breeding population, they found that female Carnaby’s Cockatoos would have to live for at least 20–25 years.

In this paper, we use data from records of individually-marked wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos to establish the maximum recorded life span of Carnaby’s Cockatoo and compare these records with what is known of other long-lived bird species in the wild.

Materials and methods

Study area and banding of individual nestlings and adults

The ecology and behaviour of one breeding population of Carnaby’s Cockatoo have been studied from 1969 to 2023 at Coomallo Creek in the northern wheatbelt of Western Australia. This population has ranged in size from 88 to 32 nesting attempts during the period 1969–1996 (Saunders and Ingram 1998) and from 41 to 146 breeding attempts during the period 2009–2023 (DA Saunders, PR Mawson and R Dawson unpubl. data). The cockatoos breed in a 9-km long, narrow belt of Wandoo (Eucalyptus wandoo) woodland that is surrounded by cleared agricultural land and uncleared native Kwongkan heath/shrublands. The Coomallo Creek site was visited at least twice each breeding season (always in September and November) during 22 of the years between 1969 and 1996. There was a hiatus from 1997 to 2008, and then visits resumed each year from 2009 continuing to 2023 (Saunders and Ingram 1998; Saunders and Dawson 2018). During each visit, every hollow known to be used by the cockatoos was inspected and contents noted. If nestlings were present, and at least three weeks old, they were measured (length of folded left wing (mm)) and weighed (g), and banded with an Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS) uniquely numbered metal leg band. In addition, 115 breeding adults were trapped and banded with an ABBBS leg band.

From 1969 to 1996, attempts were made to identify individually marked cockatoos subsequent to their banding. Carnaby’s Cockatoos have short tarsi, leg bands are narrow, and could only be read reliably by catching the cockatoos. Trapping wild cockatoos was time-consuming, stressful for the birds, and was not done often. Accordingly, identification of individuals was difficult during that period. By 2009, modern digital cameras and telephoto lenses allowed us to read leg bands without having to catch the cockatoos. In some cases, bands could be read on flying cockatoos (Saunders et al. 2011). From 2009, during each visit to the study area, every female found in a breeding hollow was photographed as it left the nest hollow to establish its identity, and flocks wherever they were encountered both within and remote from the study area, were routinely scanned for banded individuals. Resources did not permit searching for banded cockatoos in the non-breeding season, although members of the public accepted the challenge of looking for banded individuals when photographing Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Dawson and Saunders 2014) and reported their successful attempts (Saunders et al. 2024).

Comparing the maximum recorded life span of Carnaby’s Cockatoos with that of other species

In order to compare the maximum recorded life span of Carnaby’s Cockatoos in the wild with that of other long-lived species, the banding registers of Australia (ABBBS 2023), USA (US-BBL 2023), and UK (Robinson et al. 2022) were examined. Each maintains a record of the maximum recorded life span of every species banded in its jurisdiction. The maximum recorded life span of each species was tabulated in decadal ranges (0–10; 10.1–20; etc.) and all species with maximum recorded life spans of 35 years or more noted. These results were then compared with the recorded longevity of wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos reported in this study.

Ethical approval

Field work and animal handling were conducted under appropriate ethics approvals (held by CSIRO staff for 1969–1996, and Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Animal Ethics Committee project approval numbers 2011/30, 2014/23, 2017/21, and 2020/10C for 2009–2022), and bird banding approvals for the same periods (Australian Bird and Bat Banding Authority #418 held by DAS and #1862 held by PRM).

Results

Eight Carnaby’s Cockatoos (five females and three males) with life spans of at least 21 years were recorded (Table 1). All but one were alive when resighted, and all but one were within 5.7 km of where they were banded. Three were adults when banded and their ages were recorded with a ‘+’ to indicate they were at least the age indicated, but may be have been older. Four years was added to the times between banding and last resighting to account for their juvenile period, as that was the recorded age at first breeding until recently (Dawson et al. 2013).

| Band number | Date egg laid | Sex | Date banded | Location banded | Age banded | Last date sighted/recovered | Location | Status | Distance (km) from natal site | Age (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 210-03029 | 26 August 1986 | M | 17 November 1986 | Coomallo Creek | 54 days | 21 September 2021 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 5.7 | 35 | |

| 210-00459 | 5 September 1973 | M | 27 November 1973 | Manmanning | 54 days | 24 April 2008 | Hill River | Deceased, tag foundA | 177 | Circa 34 | |

| 210-01876 | F | 8 November 1988 | Coomallo Creek | 4+ years | 3 October 2014 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 0.3 | 29.9+ | ||

| 210-01652 | F | 2 November 1989 | Coomallo Creek | 4+ years | 10 September 2014 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 1.9 | 28.9+ | ||

| 210-01892 | 6 August 1989 | M | 16 November 1989 | Coomallo Creek | 73 days | 8 September 2017 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 2.0 | 28.1 | |

| 210-01790 | 24 August 1986 | F | 18 November 1986 | Coomallo Creek | 57 days | 12 September 2013 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 0.9 | 27.1 | |

| 210-01694 | 20 August 1990 | F | 19 November 1990 | Coomallo Creek | 62 days | 9 September 2012 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 2.5 | 22.1 | |

| 210-03089 | F | 21 November 1994 | Coomallo Creek | 4+ years | 9 September 2012 | Coomallo Creek | Alive, breeding | 0.2 | 21.8+ |

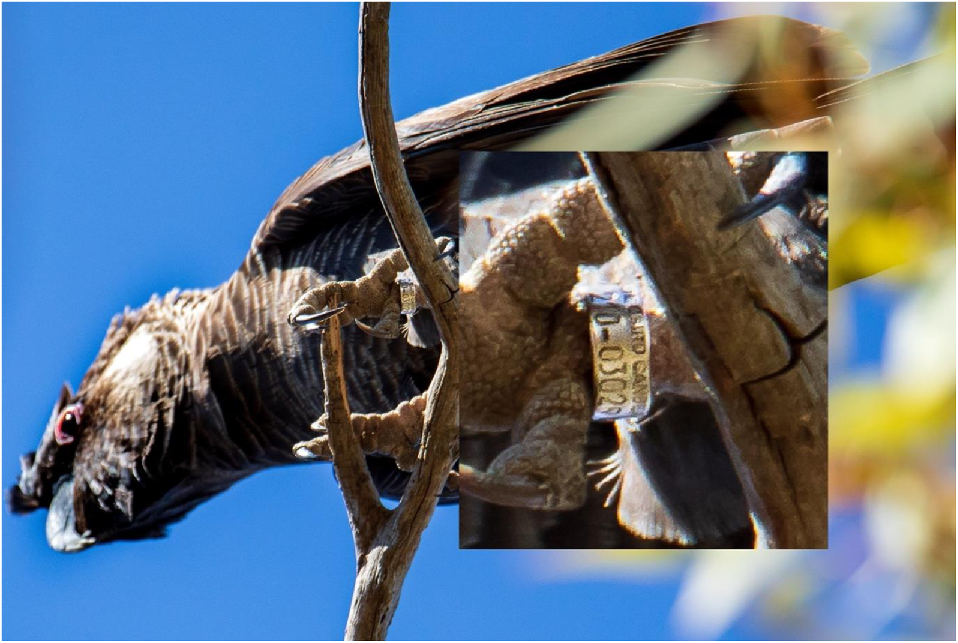

On 21 September 2021, adult male Carnaby’s Cockatoo with band number 210-03029 was photographed (Fig. 2) amongst a flock roosting in the south of the Coomallo Creek study area. The cockatoo and its leg band appeared to be in excellent condition. This sighting was the first time the cockatoo had been observed since the breeding season on 1986 when it fledged from a nest hollow 5.7 km from where it was photographed. Its estimated hatching date was 24 September 1986 and it was 35 years-old when photographed (Table 1). This is the oldest living Carnaby’s Cockatoo recorded in the wild.

Male Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) band number 210-03029 photographed on 21 September 2021, aged 35 years (photographs Rick Dawson).

Records of longevity of birds in the wild are based on records of banded/ringed individuals from studies of wild birds. Many of these studies have not been conducted long enough for research workers to answer the common question ‘How long do your birds live?’ Records from long-term central banding registers in Australia (ABBBS 2023; commenced 1953), USA (US-BBL 2023; commenced 1909), and UK (Robinson et al. 2022; commenced 1909) provide the most reliable records for the species in their jurisdictions. These registers, housing millions of records of original banding and subsequent sighting/recoveries of individual birds, show that seabirds tend to have the longest reported life spans. The species with the longest recorded life spans on the three registers are: (1) short-tailed shearwater (Ardenna tenuirostris) Temminck, 1836 found dead at 48 years and 4 months (ABBBS 2023); (2) Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) Rothschild, 1893 recorded alive when it was 69 years and 9 months (US-BBL 2023); and (3) Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) Brünnich, 1764 recorded alive at 50 years 11 months (Robinson et al. 2022).

The maximum life spans of species recorded by the Australian, American, and British band registers collated in decadal ranges are in Table 2. The data show that 96.5% of Australian, 94.5% of American, and 90.3% of British listed species had maximum recorded life spans of less than 30 years. The 31 species with maximum recorded life spans of 35 years or more on all three registers are in Table 3. All are non-passerines and 21 of the 31 species listed are seabirds.

| Decade range | ABBBS | US-BBL | BTO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of species | No. of species | No. of species | ||

| 0–10 | 433 | 245 | 81 | |

| 10.1–20 | 164 | 228 | 85 | |

| 20.1–30 | 62 | 91 | 38 | |

| 30.1–40 | 19 | 28 | 16 | |

| 40.1–50 | 5 | 3 | 5 | |

| 50.1–60 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 60.1–70 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Total | 683 | 597 | 226 |

| Scientific name | Common name | Maximum recorded life span (years:months) | Status at last recording | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABBBS | ||||

| Ardenna tenuirostris | Short-tailed shearwater | 48:04 | Dead | |

| Thalassarche chrysostoma | Grey-headed albatross | 47:02 | Dead | |

| Phalacrocorax varius | Pied cormorant | 44:09 | Dead | |

| Diomedea exulans | Wandering albatross | 44:01 | Dead | |

| Macronectes halli | Northern giant petrel | 40:01 | Dead | |

| Macronectes giganteus | Southern giant petrel | 39:04 | Dead | |

| Thalassarche cauta | Shy albatross | 36:09 | Dead | |

| Haematopus longirostris | Pied oystercatcher | 35:11 | Alive | |

| Pterodroma leucoptera | Gould’s petrel | 35:09 | Alive | |

| Zanda latirostris | Carnaby’s Cockatoo | 35:00 | Alive | |

| US-BBL | ||||

| Phoebastria immutabilis | Laysan albatross | 68:11 | Alive | |

| Phoebastria nigripes | Black-footed albatross | 60:11 | Alive | |

| Phoenicopterus ruber | American flamingo | 49:00 | Dead | |

| Thalassarche chrysostoma | Grey-headed albatross | 44:04 | Dead | |

| Fregata minor | Great frigatebird | 43:00 | Dead | |

| Haliaeetus leucocephalus | Bald eagle | 38:00 | Dead | |

| Antigone canadensis | Sandhill crane | 37:03 | Dead | |

| Onychoprion fuscatus | Sooty tern | 35:09 | Alive | |

| Diomedea exulans | Wandering albatross | 35:07 | Dead | |

| Uria aalge | Common murre | 34:08 | Dead | |

| BTO | ||||

| Puffinus puffinus | Manx shearwater | 51:00 | Alive | |

| Fratercula arctica | Puffin | 42:00 | Alive | |

| Alca torda | Razorbill | 42:00 | Alive | |

| Fulmarus glacialis | Fulmar | 41:12 | Alive | |

| Haematopus ostralegus | Oystercatcher | 41:01 | Dead | |

| Uria aalge | Guillemot | 41:00 | Alive | |

| Anser brachyrhynchus | Pink-footed goose | 38:07 | Dead | |

| Hydrobates pelagicus | Storm petrel | 38:01 | Alive | |

| Stercorarius skua | Great skua | 38:00 | Dead | |

| Morus bassanus | Gannet | 37:05 | Dead | |

| Gavia stellate | Red-throated diver | 36:00 | Dead | |

| Somateria mollissima | Eider | 35:07 | Dead | |

The record for Carnaby’s Cockatoo is from this study.

The lists derived from the central banding registers are subject to change as more birds are individually marked and the number of records of recoveries/resightings accumulate. Ehrlich et al. (1988) listed maximum recorded life spans of 53 species from US-BBL records of September 1986. The 10 maximum life span records listed by Ehrlich et al. (1988) are in Table 4, together with their records at April 2023 (US-BBL 2023).

| Scientific name | Common name | Maximum recorded life span 1986 (years:months) | Maximum recorded life span 2021 (years:months) | Status at last recording | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoebastria immutabilis | Laysan albatross | 35:05 | 69:09 | Alive | |

| Sterna paradisaea | Arctic tern | 34:00 | 34:00 | Alive | |

| Fregata minor | Great frigatebird | 30:00 | 43:00 | Dead | |

| Larus occidentalis | Western gull | 27:10 | 33:11 | Alive | |

| Uria aalge | Common murre | 26:05 | 40:08 | Dead | |

| Cygnus buccinator | Trumpeter swan | 23:10 | 26:02 | Alive | |

| Ardea Herodias | Great blue heron | 23:03 | 24:06 | Dead | |

| Branta canadensis | Canada goose | 23:06 | 33:03 | Dead | |

| Fulica americana | American coot | 22:04 | 22:04 | Dead | |

| Haliaeetus leucocephalus | Bald eagle | 21:11 | 38:00 | Dead |

Discussion

The record of a living 35-year-old Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Fig. 2) at its breeding ground places this species in the top 2% of long-lived avian species recorded in the Australian, UK, and US bird band registers. When combined with the records of seven other Carnaby’s Cockatoos ranging from 21+ to ~34 years old, six of which were still breeding (Table 1), this species needs an extended reproductive life to counter the effects of mortality rates and/or low reproductive rates. Long-term studies of birds in the wild indicate that individuals within a population age at different rates, as measured by reproductive performance, and that birds do not often survive beyond their reproductive years (Curio 1989).

It is common knowledge that birds, particularly cockatoos and other parrots, live long lives in captivity. In line with this knowledge, there is a saying in Australia, that if you are given a cockatoo for your 21st birthday, you should make provision for it in your will as it will probably outlive you. In support of this saying, there have been several reports of cockatoos living to be more than 100 years old. For example, a sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) Latham, 1790 was reputed to have died aged 120 years in Sydney in 1916 (https://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/sydneys-old-crock-of-a-cockie-was-a-legend-at-120201108311jkz2.html) – (accessed 20 August 2024). Another was reputed to have lived to 100 years old (&https://www.abc.net.au/news/20141102/wildlife-park-throws-a-100th-birthday-party-for-an-old-cockatoo/5860770?nw=0&r--=Interactive) (accessed 20 August 2024). However, these anecdotal reports are unsubstantiated.

In a review of longevity records of 176 species of Psittaciformes in captivity, Brouwer et al. (2000) noted that the life span of parrots in captivity rarely exceeds 50 years (4% of the taxa they reviewed), and that cockatoos appear to have both the longest life and reproductive spans. However, they acknowledged there were reliable records of parrots aged 65–70 years old. They cited two individuals: (1) a salmon-crested cockatoo (Cacatua moluccensis) Gmelin, JF, 1788 that died in San Diego Zoo, USA in December 1990 when it was 65 years old; and (2) a pink cockatoo (Cacatua leadbeateri) Vigors, 1831 at Brookfield Zoo, Chicago, USA, which at the time of writing, was at least 63 years and 7 months old. This individual died in August 2016, aged 83 years old. In fact, this is regarded by the Guinness Book of Records as the longest surviving bird, either in captivity or in the wild (https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/442525-oldest-parrot-ever#:~:text=The%20oldest%20parrot%20ever%20is,away%20on%2027%20August%202016 accessed 20 August 2024).

Changes over time in the avian species that have the longest recorded lifespans can be dramatic (Table 4; Ehrlich et al. 1988). For example, Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) Pontoppidan, 1763 and American coot (Fulica americana) Gmelin, JF, 1789 records did not change, but the record for Laysan albatross increased by 34 years 4 months and the bird was still alive. The record for bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) Linnaeus, 1766 increased by 16 years and 1 month, and great frigatebird (Fregata minor) Gmelin, 1789 by 13 years. This demonstrates the value of both long-term field studies of species that are faithful to studied breeding sites, and the value in re-analysing records at decadal or longer intervals.

Carnaby’s Cockatoo becomes sexually mature at 3–4 years old, pairs for life, displays natal site fidelity (females), lays two eggs, but usually fledges one young, breeds every year, has low survival in the juvenile years, high survival as adults, and is long-lived (Saunders 1982; Saunders and Dawson 2018; Saunders et al. 2018). All these characteristics are typical of the impressive oceanic wanderers, such as the albatrosses and petrels that are also in the 2% of avian species demonstrating long maximum recorded life spans.

Understanding how well the Carnaby’s Cockatoo copes with current conditions (Williams et al. 2017), and predicting what may happen in the future under conditions of changing climate requires further study to determine fledgling, juvenile, and adult survival rates. Once those rates are known, those core pieces of information can be combined with annual productivity and the species longevity and reproductive life-span to construct accurate life tables that can provide for informed decision making on where limited conservation investment can or should best be directed and in developing new species recovery plans for this species and other related black cockatoo species.

Declaration of funding

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Author contributions

Denis A. Saunders: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Peter R. Mawson: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Rick Dawson: Investigation, Writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to John Ingram for technical support 1972–1996; the Hayes, McAlpine, Paish, and Raffan families for supporting this research on their properties; the Raffan family for providing accommodation during the field work.

References

ABBBS (2023) Search the ABBBS database. Available at https://www.environment.gov.au/science/bird-and-bat-banding/banding-data/search-abbbs-database [accessed 29 August 2023]

Brouwer K, Jones ML, King CE, Schifter H (2000) Longevity records for Psittaciformes in captivity. International Zoo Yearbook 37(1), 299-316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Curio E (1989) Some aspects of avian mortality patterns. Mitteilungen Aus Dem Zoologischen Museum In Berlin 65, 47-70.

| Google Scholar |

Dawson R, Saunders DA (2014) Individually marked wild Carnaby’s Cockatoos: a challenge and opportunity for keen photographers. Western Wildlife 18(1), 4-5.

| Google Scholar |

Dawson R, Saunders DA, Lipianin E, Fossey M (2013) Young-age breeding by a female Carnaby’s Cockatoo. The Western Australian Naturalist 29(1), 63-65.

| Google Scholar |

Ehrlich PR, Dobkin DS, Wheye D (1988) How long can birds live? https://web.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/How_Long.html [accessed 5 October 2024]

Robinson RA, Leech EI, Clark JA (2022) The Online Demography Report: bird ringing and nest recording in Britain & Ireland in 2021. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford. Available at http://www.bto.org/ringing-report [created on 21 September 2022]

Saunders DA (1982) The breeding behaviour and biology of the short-billed form of the White-tailed Black Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus. Ibis 124(4), 422-455.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R (2009) Update on longevity and movements of Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo. Pacific Conservation Biology 15(1), 72-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Dawson R (2018) Cumulative learnings and conservation implications of a long-term study of the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Australian Zoologist 39(4), 591-609.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Ingram JA (1998) Twenty-eight years of monitoring a breeding population of Carnaby’s Cockatoo. Pacific Conservation Biology 4(3), 261-270.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Pickup G (2023) A review of the taxonomy and distribution of Australia’s endemic Calyptorhynchinae black cockatoos. Australian Zoologist 43(2), 145-191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Rowley I, Smith GT (1985) The effects of clearing for agriculture on the distribution of cockatoos in the South west of Western Australia. In ‘Birds of eucalypt forests and woodlands: ecology, conservation, management’. (Eds A Keast, HF Recher, H Ford, D Saunders) pp. 309–321. (Surrey Beatty & Sons: Chipping Norton, NSW)

Saunders DA, Dawson R, Mawson P (2011) Photographic identification of bands confirms age of breeding Carnaby’s Black Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Corella 35(2), 52-54.

| Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, White NE, Dawson R, Mawson PR (2018) Breeding site fidelity, and breeding pair infidelity in the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris. Nature Conservation 27, 59-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Mawson PR, Dawson R, Johnstone RE, Kirkby T, Warren K, Shepherd J, Rycken SJE, Stock WD, Williams M R, Yates CJ, Peck A, Barrett GW, Stokes V, Craig M, Burbidge AH, Bamford M, Garnett ST (2021) Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo Zanda latirostris. In ‘The Action plan for Australian birds 2020’. (Eds ST Garnett, GB Baker) pp. 402–407. (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne) Available at https://cdu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61CDU_INST/j6pesm/alma991002199119803446

Saunders D, Dawson R, Mawson PR (2022) Artificial nesting hollows for the conservation of Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris: definitely not a case of erect and forget. Pacific Conservation Biology 29(2), 119-129.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Mawson PR, Dawson R, Beswick H, Pickup G, Usher K (2024) Movements of adult and fledgling Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Zanda latirostris Carnaby, 1948) from eleven breeding areas throughout their range. Pacific Conservation Biology 30(6), PC24042.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

US-BBL (2023) Longevity records of north american birds version 2023.1 (Current Through April 2023). Available at https://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/Bander_Portal/login/Longevity_main.php [accessed 28 August 2023]

Williams MR, Yates CJ, Saunders DA, Dawson R, Barrett GW (2017) Combined demographic and resource models quantify the effects of potential land-use change on the endangered Carnaby’s cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus latirostris). Biological Conservation 210, 8-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |