Barriers to volunteering and other challenges facing community-based conservation in Aotearoa New Zealand

Charlotte P. Sextus A * , Karen F. Hytten A and Paul Perry B

A * , Karen F. Hytten A and Paul Perry B

A

B

Abstract

In many countries, community-based conservation plays an important role in protecting natural ecosystems and preserving biodiversity. However, community-based conservation groups face a variety of challenges including recruiting and retaining volunteers, maintaining relationships with stakeholders and monitoring progress towards achieving conservation objectives. In order to address these challenges, it is important to understand the barriers to volunteering, and ways to assess and improve effectiveness.

This research explores these barriers and looks at some potential solutions through a case study of community-based conservation in the Manawat region of Aotearoa New Zealand. Twenty-one in-depth, semi-structured interviews were carried out with group leaders and other key stakeholders and an online questionnaire was used to explore the experiences and perspectives of volunteers participating in community-based conservation initiatives.

Our research showed that one of the most effective ways of recruiting new volunteers was through social interaction and that the main barriers to participation were time commitment and health issues.

Relationships between volunteers, non-government organisations and government agencies impact the success of local groups, and environmental monitoring was key to obtaining funding and documenting success.

A collaborative approach creates a framework that encourages participation by empowering communities to work together on conservation initiatives, and can increase volunteer commitment. Increased recognition of the importance of Māori culture and interests will also further collaboration with Indigenous communities.

Keywords: community-based conservation, community-based environmental monitoring, environmental volunteering, leadership succession, New Zealand, volunteer recruitment, volunteer retention, volunteering barriers.

Introduction

Community-based conservation (CBC) relies on hard-working volunteers and the support of government agencies and non-government organisations (NGOs) to achieve conservation goals (Forgie et al. 2001). There are a range of factors that impact CBC effectiveness, including the capacity to recruit volunteers, barriers to volunteering, and relationships with volunteers, and other stakeholders (Forgie et al. 2001; Bushway et al. 2011; Liarakou et al. 2011; Higgins and Shackleton 2015). Community-based environmental monitoring is also important to CBC effectiveness as it allows community-based conservation groups (CBCGs) to assess their progress and apply for funding (Peters et al. 2015a, 2016; Sullivan and Molles 2016; Jones and Kirk 2018).

Environmental organisations often struggle to recruit and retain volunteers, leading to high volunteer turnover rates, and wasted time and resources in recruiting and training new volunteers (Bushway et al. 2011; Asah and Blahna 2013; Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Ding and Schuett 2020). Research into the participation in CBC has identified an array of barriers that prevent the general public from becoming involved in or continuing to be involved in CBC including a lack of awareness of opportunities (Hobbs and White 2012), time constraints, including work, study and family life balance (Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Frensley et al. 2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019; Heimann and Medvecky 2022), proximity to home (Hobbs and White 2012; Madsen et al. 2021; Thomas et al. 2021), perceived confidence and capability to participate (Hobbs and White 2012), building relationships between volunteers, iwi1 and government agencies (Forgie et al. 2001), and health issues including limited mobility (Hobbs and White 2012; Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019).

Due to the small number of volunteers in many CBCGs, there can be limited support for volunteers and leaders; this in turn can contribute to the loss of volunteers. Issues that can arise are volunteers feeling overwhelmed, being overworked, lacking a suitable role, having limited support, having inadequate training, poor organisational management, and feelings of obligation instead of satisfaction (Frensley et al. 2017; Schild 2018; Takase et al. 2019; Ganzevoort and van den Born 2020). Another important factor that influences the effectiveness of CBC is the relationships not only between volunteers but between CBCGs and other groups including iwi, NGOs, and local and regional government (Forgie et al. 2001; Wilson 2005; Peters et al. 2015b). Because CBCGs are often small and not well funded, they often rely on other groups and organisations for technical support, funding, and education and training programs. As a consequence, the success of CBCGs can be heavily impacted by the support of others, and many CBCGs would not be successful without help from other groups (Forgie et al. 2001). Local iwi play an important role in conservation efforts in Aotearoa New Zealand (Roberts et al. 1995; Taiepa et al. 1997). Both the Conservation Act 1987 (NZ) and the Resource Management Act 1990 (NZ) explicitly require all persons exercising functions and powers under them to give effect to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (Ti Tiriti o Waitangi) (Environment Foundation 2018). Therefore, giving effect to the Treaty principles are crucial considerations for government agencies and community organisations involved in conservation management.

Community-based environmental monitoring is also key to effective CBC as it allows a CBCGs to track progress and success, allowing CBCGs to adjust their work accordingly to achieve conservation goals. Community-based environmental monitoring, also sometimes referred to as volunteer monitoring or participatory resource monitoring, is a form of citizen science where volunteers track changes in species abundance and distribution, measure ecosystem health and, in some instances, provide data for local, regional and national decision making (Dickinson et al. 2012; Gura 2013; Peters et al. 2015a; Galbraith et al. 2016; Orchard 2019). Community-based environmental monitoring can range from a simple one-off experiment to an expansive, long-term study (Dickinson et al. 2012), and is used for a wide variety of reasons including large scale data collection (Dickinson et al. 2012; Silvertown et al. 2013; Peters et al. 2015a; Galbraith et al. 2016); education (Crall et al. 2013; Gura 2013); building relationships between local people, businesses and government (Peters et al. 2015b); and to help with CBC management (Conrad and Hilchey 2011; Orchard 2019). Some examples of community-based environmental monitoring methods employed by CBCGs include species counts (to monitor species abundance and distribution by counting species in a given area), photo points (to track progress of a specific area by periodically taking photos from the same location), pest tracking tunnels (to identify and track the abundance of pest species in the area by footprint tracks) and 5-min bird counts (to identify the presence of bird species in an area by their call) (Sher and Molles 2022). Community-based environmental monitoring has become a common method for carrying out long term conservation studies and is often required when CBCGs apply for funding and grants (Dickinson et al. 2012; Silvertown et al. 2013).

In order to recruit new volunteers and reduce turnover rates, CBCGs need to have an understanding of the key barriers that restrict people from volunteering, and what can be done to alleviate them. There also needs to be clearer planning and the implementation of community-based environmental monitoring to track progress and allow CBCGS to obtain funding, along with strong relationships between local groups and other organisations. This research aims to address four key questions within the context of the Manawatū region of Aotearoa New Zealand: (1) What are the key barriers to CBC volunteering? (2) What can be done to improve volunteer retention? (3) How can strong relationships between CBCGs relevant stakeholders be developed? (4) How can CBCGs be encouraged and supported to implement community-based environmental monitoring?

This research contributes to the growing literature on the CBC, and the limited studies carried out in Aotearoa New Zealand. In particular, this research seeks to fill a gap in the literature by interviewing and surveying local volunteers in the Manawatū region. The Manawatū region was selected for this study as the region has been greatly impacted by native habitat loss and the introduction of mammalian predators. Therefore, this region is in dire need of ecological restoration, habitat protection and targeted predator control (Craig et al. 2000; Jones and Kirk 2018). The Manawatū region is also a good place for a case study as the region’s demographic characteristics are close to the New Zealand average (McKinnon 2015; Stats NZ 2018a). As such, as well providing insights into the local context, the findings of this study can inform CBCG efforts to recruit and retain volunteers across Aotearoa New Zealand. This study is relevant to a variety of fields including conservation biology and environmental management.

Materials and methods

This paper examines the barriers and challenges faced by CBC volunteers in the Manawatū region of Aotearoa New Zealand. A mixed-methods approach was used including a desktop study of local CBCGs, semi-structured interviews with CBCG coordinators and stakeholders and a questionnaire for CBC volunteers.

The Manawatū region is located in the lower half of the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand (Fig. 1). The main population centre is Palmerston North with a population of approximately 85,000 (Stats NZ 2018b). There are also several smaller towns including Feilding, Woodville, Dannevirke, Pahiatua and Foxton. The Manawatū River runs through the Manawatū and is 235 km long with a number of large tributaries including the Oroua, Mangatainoka, Mangahao, Pohangina and Tiraumea (Land Air Water Aotearoa 2024). The catchment includes a series of mountain ranges notably the Tararua and Ruahine ranges, and plains that extend between the ranges and the sea.

The Manawatū has several areas of ecological significance including the Manawatū Gorge Scenic Reserve, and the Manawatū Estuary that is an internationally recognised Ramsar site at Foxton Beach (National Wetland Trust of New Zealand 2023). The Manawatū is known for its agricultural sector, which includes dairy cattle farming, sheep and beef cattle farming (Figure NZ Trust 2023); (1) Massey University; (2) the Universal College of Learning; and (3) the Institute of the Pacific United. As a result, it has an unusually high proportion of highly-educated residents for a town of its size, including a large number of tertiary students as well as many current and retired academics.

Desktop study and systematic review

A preliminary online investigation was carried out to identify all CBCGs currently operating in the Manawatū. The websites of The Environment Network Manawatū (ENM)2, Forest and Bird3 and the Department of Conservation (DOC) were examined in order to find all relevant groups based in the Manawatū, which have conservation-based objectives. In total, 21 CBCGs were identified. These groups carry out a wide variety of tasks including predator control, planting native vegetation, weeding, growing native plants, habitat restoration, education, advocacy, and litter collection. For a summary of the information collected about each of the CBCGs, see Supplementary material Table S1.

A systematic literature review was then carried to identify, synthesise and analyse the peer-reviewed literature on motivations of environmental volunteers to pinpoint key factors influencing volunteer motivations, barriers and satisfaction, and develop the interview and questionnaire instruments (see Sextus et al. 2024a). In particular, key sources that contributed to developing the interview and questionnaire questions included: Clary et al. (1998), Ryan et al. (2001), Bruyere and Rappe (2007), Hvenegaard and Perkins (2019) and Heimann and Medvecky (2022).

Semi-structured interviews

After obtaining ethics approval in accordance with the Massey University Code of Ethical Conduct for Research, Teaching and Evaluations Involving Human Participants, each of the 21 CBCGs, ENM, Forest and Bird and DOC were contacted via email and invited to participate in a semi-structured interview. A representative from DOC and ENM, and representatives from 12 CBCGs were interviewed. These interviews provided a comprehensive overview of the local CBCGs and their volunteers, with a particular focus on individuals’ motivations to participate in CBC volunteering and barriers and challenges faced by volunteers and groups. A total of 21 interviews were conducted between November 2020 and April 2023.

Each interview was approximately 45 min and consisted of nine open-ended questions for CBCG volunteers and an additional three questions for CBCG leaders and other representatives (Supplementary material file S1). Interviewees were asked about their CBCG and volunteers, and about their own personal experiences and motivations for volunteering. They were also asked about their perception of the motivation of other volunteers, limitations and issues around recruitment and retention and other challenges. Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and analysed for key themes. The issues and themes raised in the interviews, together with insights from the literature informed the development on the questionnaire for CBC volunteers.

Questionnaire

Additional data was collected via an online questionnaire consisting of short answer and multiple-choice questions, with a section at the end for participants to share any other thoughts or experiences. The online questionnaire was created and administered using Qualtrics (qualtrics.com); there was also a paper version provided at the ENM office and available upon request. Respondents had to be a volunteer, or have previously volunteered in a CBCG, in the Manawatū region. The questionnaire was open from 29 October 2021 to 24 February 2022.

Recruitment for the questionnaire was carried out using both targeted and snowball sampling (Sarantakos 2013; Denscombe 2014). Volunteers were reached via an email with a link to the questionnaire sent from the ENM to all its active members; an advertisement was also placed in the ENM newsletter. Each CBCG that was identified in the desktop study was also sent the same email to their listed contact email address. Recipients of the email received a link to the questionnaire with an invitation to send it on to all their volunteers or past volunteers. The questionnaire invitation included a short summary of the study, a link to the online questionnaire, and an option to have a paper version delivered to them if required. The questionnaire had 101 respondents, representing 21 CBCGs, and respondents from ENM and DOC. Seventeen of the 21 CBCGs identified in the desktop study, were represented along with four additional CBCGs that were not identified in the desktop study.

The questionnaire was designed to provide a well-rounded picture of the characteristics, behaviours, motivations of CBC volunteers in the Manawatū, and was developed from relevant literature and from information obtained from face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire consisted of 43 questions, which covered volunteering details, demographics of volunteers, motivations for environmental volunteering, commitment and satisfaction, barriers to volunteering, environmental monitoring, relationships with iwi and government organisations and attitudes towards pro-environmental behaviours. The responses to the questionnaire were first analysed using Qualtrics and then synthesised in the context of the key themes identified from the systematic literature review and the semi-structured interviews. The findings relating to barriers to CBC volunteering, volunteer recruitment, building relationships between stakeholders and environmental monitoring are described and discussed below (for the findings relating to long-term CBC volunteer motivations, volunteer commitment and satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours please see (Sextus et al. 2024b).

Limitations

The key limitation of this study is that we were unable to obtain a random representative sample. The total number of CBC volunteers in the Manawatū is unknown and there is no list of current volunteers from where to select a random sample. Therefore, we attempted to reach as many CBC volunteers as possible using the strategies outlined above, including sharing the online questionnaire as widely as possible and making a paper copy of the questionnaire available to volunteers who might prefer to participate offline.

Results

Characteristics of volunteers

The interviewees represented a variety of CBCGs from small groups consisting of approximately six volunteers to larger CBCGs with 30–40 volunteers. Interviewees were mostly leaders or long term volunteers of CBCGs within the Manawatū; however, some were also trustees and paid co-ordinators or employees of CBCGs. We also interviewed a representative from ENM and DOC. There was a wide age range among volunteers; from the youngest in their 20s to a large proportion of older, retired individuals. There were slightly more females than males. Many of the interviewees had degrees in a range of fields. All interviewees were extremely happy to discuss their CBCG and the role they play in conservation efforts in the Manawatū.

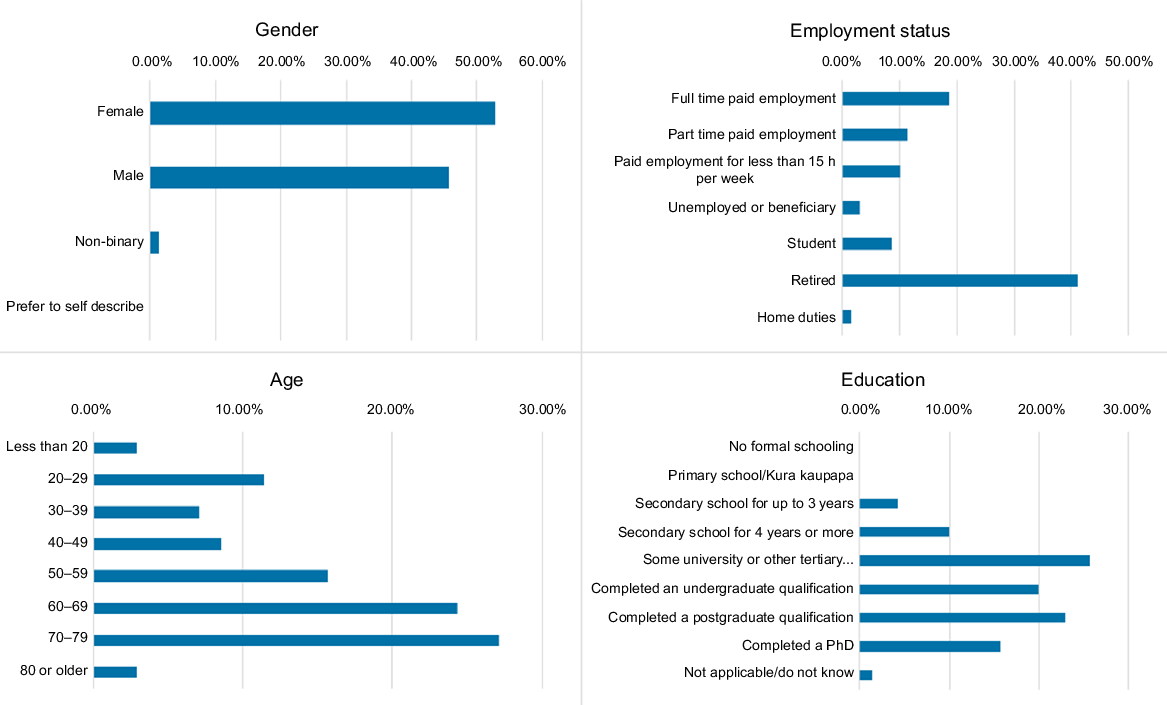

Volunteers who responded to the questionnaire tended to be older, highly educated, and either retired or in part time employment. There were slightly more females (53%) than males (46%). There was a wide age range among the volunteers, with a high proportion of older individuals (70% of respondents were over 50 years old). The volunteers also tended to be highly educated with 85% of volunteers having some form of tertiary education. The largest group of respondents were retired (47%), followed by those in paid employment for less than 30 h per week (21%) (Fig. 2).

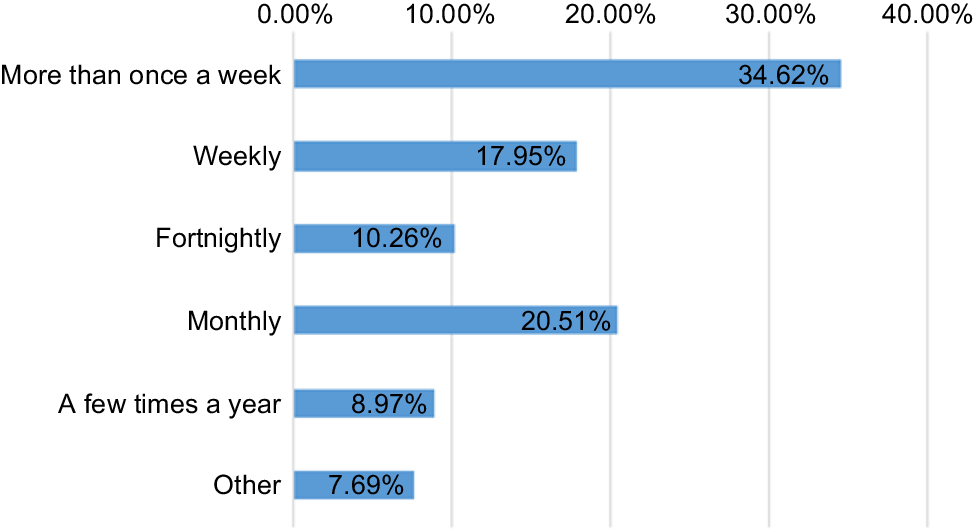

Respondents had volunteered in CBC activities from a few months to over 40 years, with the highest proportion of respondents having volunteered between 1 and 5 years (41.9%), and the smallest proportion for 16–20 years (5.4%). There was also a range of volunteering frequency with the highest proportion of respondents volunteering more than once a week (34.6%) (Fig. 3).

Volunteer recruitment

Interviews with local CBCG representatives revealed that recruitment is a barrier to effective CBC:

It’s a big issue. I’ve had various attempts at getting the community involved with limited success, but because I’m so busy and the lack of interest I essentially gave up. (CBCG member)

[We recruit volunteers] with difficulty, actually. It’s very, very difficult. We promote it on our Facebook page. One of the issues I have had is that I always respond to volunteers offering to come but for whatever reason they then don’t turn up. It’s probably a 50% success rate of going out to the community and saying will you come and help? (CBCG leader)

There was typically a limited effort put into recruiting new volunteers and it tended to be left to interactions with current volunteers or through social media, as explained by two interviewees:

It’s word of mouth, people who know people. We do sometimes post on Facebook. (CBCG leader)

They pretty much recruit themselves. We do posts every now and then on social media saying we want some extra volunteers, or people, word of mouth is handy. We basically just try to get our name out in the community. (CBCG employee)

It’s word of mouth, people who know people. Often people have become a bit lonely and would like to have some input, social interaction. (CBCG leader)

Word of mouth or people see an article in the guardian or stumble across our website or have been dragged into some volunteering by a family member. We are really open to any group with an interest. (CBCG co-ordinator)

We just use the Facebook page, it’s all locals. Most people have been involved from quite early on. (CBCG leader)

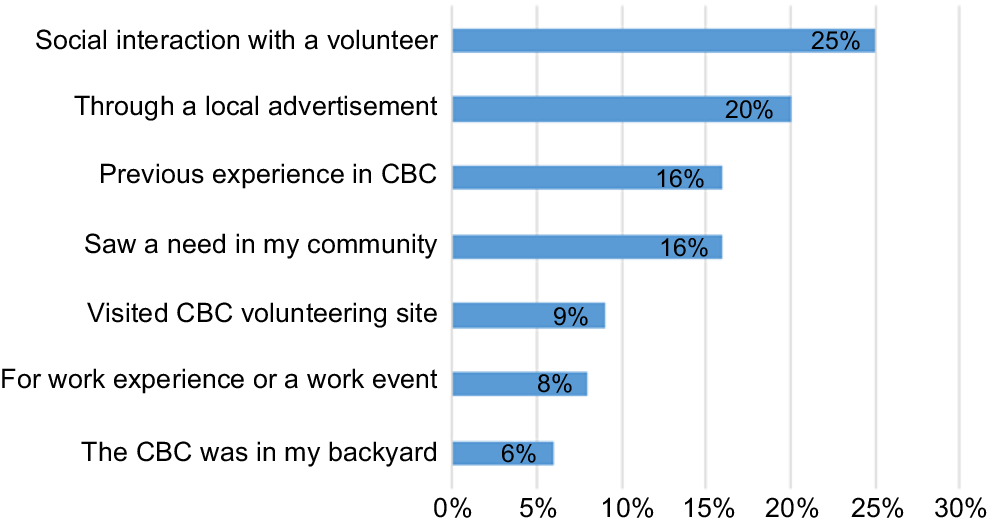

Questionnaire respondents were asked ‘How did you come to join your environmental group?’. The top types of recruitment were a social interaction with a volunteer (25%), a local advertisement (20%), having previous experience in CBC (16%), or seeing a need in their local community (16%) (Fig. 4). Of all the respondents 67% had brought another individual to their CBCG at least once and individuals who were brought along often attended multiple times, with 37% attending a few times, and 47% attending regularly.

Barriers to community-based conservation volunteering

When asked ‘Are there any factors that make it difficult, or which limit your ability to volunteer?’, 58% of questionnaire respondents stated that there are factors that sometimes make it difficult for them to volunteer. The most frequently mentioned factors were health issues, working and/or studying, family commitments and time constraints. Other barriers identified by some respondents included lack of funds, inability to keep up with technology, the negative impact of COVID-19, and the lack of non-physical options.

On a scale of 1–5 where 1 was not limiting and 5 was very limiting, respondents were asked to rate a series of barriers that were found to be common in the literature about CBC. Out of a range of common barriers, time taken ( out of 5), travelling distance (), and health issues () were identified as the most likely to limit respondent’s participation in CBC (Table 1). However, no barriers were identified as being very limiting to respondent volunteering.

| Barrier to volunteering | Mean | s.d. | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time taken | 2.87 | 1.48 | 2.2 | |

| Travelling distance | 2.31 | 1.47 | 2.16 | |

| Health issues | 2.07 | 1.35 | 1.81 | |

| Lack of resources | 1.9 | 1.28 | 1.64 | |

| Lack of activity relevance | 1.85 | 1.26 | 1.6 | |

| Lack of activity options | 1.63 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

Time was also identified as a key barrier in interviews with CBCG leaders who reported often finding it difficult to get volunteers to commit their time to volunteering especially when volunteering sites were not local:

It’s super time consuming and when you don’t have much spare time it’s a big ask. (CBCG volunteer)

Because people have to travel, its [[sic] far more drop in, drop out. People don’t stick around and having to train people means there is too much admin for little return. (CBCG leader)

Improving volunteer retention

Questionnaire respondents were asked if there were any reasons that would cause them to stop volunteering for their CBCG. The most frequently mentioned reasons were future health issues or an inability to do the work, moving out of the area, needing to work more hours or getting a full-time job, conflict with other volunteers, and when they no longer can make a useful contribution. This was also reflected in answers from interviewees:

Work got too busy, work clashes with time of working bee, one volunteer got injured on a tramp, and some moved out of the area. We are learning and we are improving the way we do things. (CBCG leader)

Peoples’ priorities in life change, they have families or different work commitments. (CBCG co-ordinator)

They (volunteers) don’t leave the group, they just hover in the background. (CBCG leader)

Some (volunteers) have taken a back seat but we can call on them and we do when we need something. (CBCG trustee)

Forty-three percent of respondents knew of someone who had stopped volunteering for their CBCG. The perceived reasons for leaving were very similar to the respondent’s reasons stated above and included getting a full-time job, moving out of the area, health issues or death, lack of appreciation, conflict with other volunteers, and frustration at lack of action from the local council.

Interviews with local CBCG representatives revealed that some groups deliberately ensure that they offer a range of tasks that allows older volunteers or volunteers with limited mobility to continue to volunteer:

We split the jobs because there is so much to do. There’s the visitor hosting side of things which is suitable for the people that aren’t super mobile or physical and some people just like chatting to people out there. (CBCG employee)

We have some older retired people who absolutely love coming in but can only do a few hours a month or they are off for a hip replacement or something like that, so they are away for months and then come back. (CBCG employee)

We accept anyone for who they are, people know they can come and do as much as they are able to do and we will find a job that fits their ability. One lady used to be an active member of the planting side of things but as she has gotten older she can’t do that so every month she organises the morning tea. (CBCG leader)

Other opportunities to improve volunteer retention that were raised by interviewees included:

In order to get the most out of the time that the volunteers are with you, it’s got to be prepared. Otherwise, people go away saying gosh that was a muddle or we didn’t really achieve what we wanted to do. (CBCG leader)

I try to give people choices so that if their uncomfortable about doing something there’s another thing that they could do. (CBCG leader)

An issue that was mentioned by interviewees that was not addressed in the questionnaire was the need for funding to pay for co-ordinators, and the lack of leadership succession:

I think the biggest challenge for most environmental groups is that it’s easy to for us to get funding for plants or for traps. It’s very hard to get co-ordinator time funded and a lot of our groups run on volunteer goodwill, when you get to a certain point, you can’t expect volunteers to do that. It’s got to be somebodies job. (CBCG co-ordinator)

The pollution challenge got a grant and so we had a co-ordinator and that’s a critical thing. I mean funding for a paid co-ordinator makes a big difference. (CBCG volunteer)

The energy of one or two key people is critical, both of those women (a CBCG leader and co-ordinator) make real contributions to the community. Succession is a big issue with volunteer groups for sure. (CBCG volunteer)

Relationships between CBCGs, local council and other stakeholders

Interviews with local CBCG representatives revealed that there is a need for better communication and relationships, between local council and CBCGs:

Volunteers will leave, because they think that their work wasn’t recognised enough by council. Why do it, if it should be done by council? (CBCG trustee)

They [the Council] should be facilitating and enabling the community to grow in conservation. (CBCG member)

Eighty-six percent of respondents stated that their CBCG liaises or collaborates with local and regional council, 4% said they do not, and 10% were unsure. Most respondents believed that collaboration with local and regional councils was important for the success of their group (m = 4.29 out of 5, where 1 is ‘not important’ and 5 is ‘very important’) (Table 2). However, only 19% of respondents thought that there were ways to improve collaboration. More communication, an increase in funding and grants that aligned with the needs of CBCGs, building personal relationships with councillors, hiring more competent people, and for councils to be willing and able to make more of an effort to help CBCGs were some of the ideas mentioned by respondents.

| Mean | s.d. | Variance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local and regional council | 4.29 | 1.14 | 1.29 | |

| Department of Conservation | 3.97 | 1.29 | 1.65 |

Fifty-seven percent of respondents identified that their CBCG liaises or collaborates with the DOC, 12% said they do not, and 32% were unsure. With respondents stating that collaboration was important (m = 3.97 out of 5) (Table 2). Only 14% of respondents thought something can be done to increase collaboration. Some ideas mentioned by respondents include better communication, more support programs, ensuring competent people are in charge, and for DOC to listen to CBCGs and allow them to have a say in decisions in the planning stage of local conservation initiatives.

Fifty-four percent of respondents stated that their CBCG liaises or collaborates with local iwi, 19% stated that their CBCG does not, and 26% were unsure. Only 17% of respondents believed that an increase in collaboration with iwi is possible; they mentioned that some ways collaboration could be improved included having more patience, time and understanding towards each other, having local iwi on board, and taking time to build relationships between iwi and CBCGs.

Community-based environmental monitoring

Questionnaire respondents were asked ‘As far as you know does your environmental group/s carry out any sort of monitoring? If yes, what type of monitoring?’. Fifty-six percent of respondents stated that their CBCG carried out some form of monitoring. However, only 33% of respondents reported being personally involved in any monitoring. Respondents also displayed varying understandings of what monitoring involves, with some respondents stating that they observed but never took notes or collected any sort of data. The most frequently mentioned types of community-based environmental monitoring were recording the number of pests caught in traps, undertaking bird counts, monitoring plant survival rates, counting and classifying rubbish collected from streams, undertaking pest monitoring (e.g. using tracking tunnels), monitoring native bird recovery rates, undertaking water quality tests, and monitoring plant growth (Table 3). Overall respondents who were involved in community-based environmental monitoring found it enjoyable with an average of 3.91 out of 5 (where 1 is ‘not enjoyable’ and 5 is ‘very enjoyable’).

| Types of community-based environmental monitoring | Number of volunteers that stated they carry out each type of monitoring | |

|---|---|---|

| Pest trapping | 15 | |

| Bird counts | 12 | |

| Plant survival rates | 11 | |

| Pest monitoring | 9 | |

| Rubbish collection | 6 | |

| Bird health | 6 | |

| Plant growth | 5 | |

| Water quality | 4 | |

| Plant numbers | 3 | |

| Butterfly tagging | 2 | |

| Succession of plants | 1 | |

| Dune regression | 1 | |

| Peat control | 1 | |

| Bird survival rates | 1 | |

| Soil testing | 1 | |

| Total | 78 |

Interviewees were also asked about environmental monitoring, and it was clear that many CBCGs were not involved in environmental monitoring and that there was a need for more CBCGs to get involved:

Citizen science is not viewed highly at all. (CBCG employee)

We need to be actively monitoring those trees that we put in. We want to be as sure as we can that we are achieving our aim, which is basically biodiversity. (CBCG leader)

Green corridors could do so much more, in terms of monitoring, particularly in terms of the trees they plant. (CBCG volunteer)

Discussion

This section discusses the key barriers to effective CBC identified above: challenges associated with volunteer recruitment; barriers to volunteering and how they can be mitigated; building and maintaining relationships with stakeholders; and the importance of community-based environmental monitoring.

Volunteer recruitment

A key barrier to effective CBC is volunteer recruitment, due to the sometimes sporadic nature of volunteer participation. For many groups, high volunteer turnover means there is a need for ongoing recruitment of volunteers. New volunteers can help to expand the efforts of the group, help reduce burn out by allowing volunteers to step back when needed, and therefore have a positive impact on the success of CBC (Forgie et al. 2001). This is not true for all CBCGs as it is common for CBCGs to have a committed core group of volunteers who maintain a successful CBCG without the need for additional volunteers. However, it is nonetheless important to understand what recruitment methods are the most likely to attract new volunteers (Bushway et al. 2011; Frensley et al. 2017; Ding and Schuett 2020; Thomas et al. 2021). The top recruitment method reported by our respondents was social interaction with an existing volunteer. However, it only accounted for a quarter of individuals and other methods also played a key role in recruiting volunteers. A study by Heimann and Medvecky (2022) found that just over 64% of their volunteers were recruited by a social interaction (either hearing about the opportunity through personal contacts, or being actively recruited by a member), rather than an advertisement. A study by Ding and Schuett (2020) had similar findings and stated that a personal request by a volunteer and a positive atmosphere for communication were key in recruiting new volunteers. Employing a variety of approaches to recruit volunteers would likely be beneficial for CBCGs in the Manawatū and elsewhere.

Volunteer recruitment and turnover is an issue for many environmental groups that rely on volunteers (Bushway et al. 2011; Asah and Blahna 2013; Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Frensley et al. 2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019; Ding and Schuett 2020), with some studies finding that turnover is increased with higher proportions of older volunteers (Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019). For example, in a study by Hvenegaard and Perkins (2019) that looked at recruitment in volunteers who walked trails and maintained Bluebird nest boxes, only 18% had successfully recruited someone to take over their trail and 14% were not going to attempt to recruit another volunteer. CBCGs would benefit from having a succession plan in place for both volunteers and leaders, so that if volunteers do leave, there is someone to replace them. This is particularly important for predator trapping, as if traps are not cleared and reset regularly mammalian predators will re-inhabit the area. There are a range of factors that may hinder the ability of CBCGs to recruit new volunteers, and it is crucial that co-ordinators understand these barriers to volunteer participation so they can be mitigated (Bushway et al. 2011; Higgins and Shackleton 2015). Lack of time is a major barrier to volunteering in our study and other studies (Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Frensley et al. 2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019), and there is often a conflict between family and work commitments and volunteering. In order for an individual to consider volunteering they must have enough energy and time to spare and be able to fit volunteering around other commitments. Volunteer expectations can also impact recruitment, as it is necessary to promote the positive side of volunteering to attract volunteers. However, it is also important that expectations are realistic so volunteers do not leave when they experience the mundane or negative aspects of volunteering (Measham and Barnett 2008; Kramer and Lewis 2020). Other individuals’ views can also impact the ability to recruit volunteers, as close family and friends could be supportive and encourage volunteering or hinder and cast doubt on the matter (Kramer and Lewis 2020). In order to address these issues, it is important that communication with potential volunteers portrays volunteering work as a meaningful and purposeful experience and promotes flexibility in commitment and roles to work around other commitments (Hong and Morrow-Howell 2013; Kramer and Lewis 2020).

There are a variety of methods to help improve recruitment rates mentioned in the literature. Targeting specific demographic groups is identified as one way to bolster recruitment. A study by Ding and Schuett (2020) found that there is a peak in generative concern in middle age, and suggested that targeting middle aged and older individuals would increase recruitment rates. Targeting a specific age group means that recruitment methods can be delivered in a way that specifically attracts that demographic. Aligning volunteering tasks with volunteer motivations has also been identified by several studies to have a positive impact on recruitment, especially recruitment of individuals with diverse interests and backgrounds (Bushway et al. 2011; Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Frensley et al. 2017). Conservation initiatives that are intertwined with prominent issues in the community, and complement individual’s interests and previous experiences can also help promote participation in CBC (Bonney et al. 2009; Frensley et al. 2017). One way of achieving this may be to work together with other local groups or an umbrella group (such as ENM) so that potential volunteers could be directed towards a group that matches their interests, skill set, availability, and motivations.

Barriers to community-based conservation volunteering

While volunteer recruitment is essential, it is even more desirable to retain current volunteers instead of constantly having to find and train new individuals. The most commonly mentioned barrier by CBC volunteers in the Manawatū was time, which consists of a few aspects including time taken to travel to the volunteering site, the time the volunteering tasks take, and the timing of working bees and events. Time has also been identified as a key barrier in a number of previous studies. Hvenegaard and Perkins (2019), Higgins and Shackleton (2015), and Frensley et al. (2017) all stated that time commitment was one of the top barriers to volunteering. A high proportion of volunteers in the Hvenegaard and Perkins (2019) study stated that time was a key barrier to commitment, and time was noted as a top reason for dropping out of the project in Frensley et al.’s (2017) study.

Managers of CBCGs can try to address this challenge by setting clear expected time frames, and by providing different options for involvement (Frensley et al. 2017), including options to volunteer at a variety of times, and to have volunteering opportunities that vary in length of time. With small CBCGs it may be worth working with other groups in order to be able to provide these options. If a volunteer site is some distance from a township, transport could be provided to encourage more volunteers to attend. Offering volunteers a variety of options in terms of when and duration that they can participate will allow volunteers who have limited time to still make a contribution, and may help reduce turnover rates (Hong and Morrow-Howell 2013; Higgins and Shackleton 2015; Frensley et al. 2017).

Health benefits to volunteers are frequently mentioned in the literature around environmental volunteering (O’Brien et al. 2010; Hobbs and White 2012; Zuo et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2022; Patrick et al. 2022). However, health issues are also a significant barrier especially given the high number of older volunteers. Given the high proportion of older volunteers, it was unsurprising that issues around health were often mentioned as a barrier to volunteering in CBCs in the Manawatū. A study by Hvenegaard and Perkins (2019) stated that poor mobility, getting older, and even death were mentioned by volunteers as reasons to stop volunteering. Another study by Pope (2005) also found that poor health was a barrier to environmental volunteering. Therefore, it is important that there are options in place to help individuals with health issues or declining health to continue to volunteer. CBCGs could encourage volunteering in individuals with health issues by being flexible in commitment levels (Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019), supporting volunteers reducing volunteering hours (Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019), offering a range of tasks that include non-physical options, and being aware of changes in volunteer motivations over time (Bramston et al. 2011; Frensley et al. 2017; Pagès et al. 2018; Schild 2018; Larson et al. 2020).

Several of the groups in the Manawatū already have a range of tasks that allows older or mobility limited people to continue to volunteer. If volunteers are supported and offered alternative tasks it means that they can still make a contribution and feel useful, and are therefore more likely to continue to volunteer. Being understanding of individual’s situation and having a diverse group of volunteers would also be helpful in reducing the impact of individuals with health issues. If individuals needed to cut back on volunteering or change their role, other volunteers would be able to cover or swap tasks with them.

Simply using volunteers as a workforce is not enough to retain volunteers, leaders must be aware of volunteer motivations and take steps to prevent burnout and high turnover rates (Measham and Barnett 2008; Asah et al. 2014; Takase et al. 2019). Due to many CBCGs having a small number of volunteers, volunteers can often be overworked, have limited support, feel obligated to participate, and have limited training opportunities, leading to an increase in volunteers burning out and/or leaving (Frensley et al. 2017; Schild 2018; Takase et al. 2019; Ganzevoort and van den Born 2020). Just over 40% of respondents knew someone who had stopped volunteering; some of the top mentioned reasons were increasing hours at work, health issues, lack of appreciation, and the breakdown of relationships. Being aware of key reasons why people decide to stop volunteering can allow CBCG leaders and environmental agencies to mitigate this issues. For example, ‘lack of appreciation’ can be addressed by having an appreciation plan in place where each volunteer is individually thanked after volunteering either in person or via an email, or a thank you afternoon tea could be held a few times a year to thank all volunteers.

Like many CBCGs around the world, most of the CBCGs in the Manawatū are quite small and tend to be kept alive by one or two committed volunteers. While these individuals deserve to be recognised and applauded for all their hard work, they also need other volunteers to step in to give them regular breaks and additional volunteers with the knowledge and skills to take over when they want to take on a less committed role. The literature identifies several challenges around leadership succession in CBCGs (Froelich et al. 2011; Pagès et al. 2018; Li 2019). The succession of leaders is important, and has been identified as a reason why volunteer groups disband. CBCGs need to be able to anticipate and manage the succession of leaders by having a plan in place to effectively prepare for leadership transition and development (Froelich et al. 2011; Li 2019). In order for leaders to have the ability to take the time to support volunteers and make them feel satisfied, they also need to be supported and have volunteers that can assume leadership roles as required. Future leaders can be recruited from within or outside of a CBCG, and depending on the size of the group, it may be the responsibility of the current leader, management, or board members to recruit a future leader (Johnson 2022). Time and effort must be put into developing or finding future leaders. One way of achieving this is for current leaders to empower prospective leaders by listening to their needs and working alongside them as role models (Froelich et al. 2011; Johnson 2022). Smaller CBCGs often do not have the capacity to train new leaders and therefore will recruit outsiders to fill a gap in leadership (Johnson 2022). Another way to reduce the impact of leadership succession is to have multiple leaders who work together, to achieve group goals, and train volunteers (Froelich et al. 2011; Johnson 2022). It is key that there is open dialogue between current leaders, prospective leaders, and management to ensure a smooth transition (Johnson 2022).

Relationships between CBCGs, local council, and other stakeholders

Multiple groups are involved in conservation in Aotearoa New Zealand, including local residents, iwi, NGOs, and government organisations (Forgie et al. 2001; Wilson 2005; Peters et al. 2015b). Relationships between these groups are important, as CBCGs often rely on other groups and organisations for funding, technical support, and education. These groups often have differing views of conservation, and incorporating multiple perspectives can impact the success of conservation initiatives (Forgie et al. 2001).

Local councils play an important supporting role to CBC, by facilitating increased cooperation and communication between CBCGs, and providing practical guidance and financial support. Horizons Regional Council’s stated goal is to ‘work in partnership with our communities to protect and enhance our patch of native New Zealand’, by working alongside communities to empower them to reconnect with, protect and enhance native areas including the Manawatū Gorge, Manawatū River and Totara Reserve (Horizons Regional Council 2024a). They offer a range of environmental education opportunities that aim to increase environmental knowledge and awareness of environmental issues, with the goal of fostering behaviours’ and actions that lead to positive environmental change (Horizons Regional Council 2024b). Horizons also offers yearly funding for local community projects with environmental goals (Horizons Regional Council 2024a). The Palmerston North City Council (PNCC) ‘plays its part in regenerating biodiversity within its rohe4 by re-establishing bush, particularly along walkways; controlling introduced predators; working in partnership with iwi; supporting community efforts’ this is made possible by partnering with iwi and supporting CBCGs (Palmerston North City Council 2018, 2021). Our findings suggest PNCC has been successful in building relationships with CBCGs as the majority of local CBCGs (86%) have some form of collaboration with PNCC. These relationships and partnerships have allowed PNCC to further suppress pests, increase riparian plantings at stream margins, plant native trees to attract birdlife into the city, enhance freshwater ecosystems, and protect more habitats of local significance. PNCC plan to incorporate Māori knowledge into council practice and ensure that iwi have a primary role in environment decision-making, and strengthen Māori involvement in conservation efforts (Palmerston North City Council 2018, 2021). However, there is still a need for better communication and relationships with CBCGS and local council. In order to strengthen the relationship between council and CBCGs, it is important that council have well-paid and properly trained staff in place to help CBCGs and that CBCGs are able to play a meaningful role in the initial decision making around local conservation initiatives and projects. A positive example of the council working closely with the community is the PNCC working alongside ENM to distribute funding via the Environmental Initiatives Fund that provides local CBCGs with access to funding to carry out local conservation goals and in turn improve environmental outcomes in the Manawatū.

DOC is responsible for conserving Aotearoa New Zealand’s natural and historic heritage (Department of Conservation 2023). DOC has an integrated ecosystem management framework for CBCGs that allows for coordination between different natural resource management agencies, and local communities across entire ecosystems. The key features of this type of management framework include: managing ecosystems as a whole; integrating legislative requirements of a range of natural resource management agencies; encouraging collaboration between government agencies, iwi and local communities; and having adaptive approaches that can change depending on social, economic and cultural issues (Department of Conservation and Ministry for the Environment 2000; Forgie et al. 2001). Our research suggests that although in principle DOC promotes and supports collaboration with CBCGs, there is limited practical support for CBC in the Manawatū, with just over half of the CBCGs in the Manawatū collaborating with DOC. Our research also pinpoints some key aspects that would improve communication between DOC and CBCGs, which includes allowing CBCGs to have more of a say in local conservation initiatives, increasing support and training programs, and having more on the ground technical support. There was also a desire from CBCG representatives to have more qualified people looking after CBCGs and their volunteers. Forgie et al. (2001) argue that in order to get communities involved in solving environmental issues, there needs to be a change in local communities’ attitudes and behaviour. A collaborative approach that allows government agencies to act as stakeholders, creating a framework that encourages participation, and supporting and empowering CBC initiatives, allows communities to come together to decide values, goals and strategies for themselves meaning they are more likely to be committed to the cause. Addressing complex environmental issues is dependent on changing peoples’ attitudes and behaviours in order to promote active engagement. Therefore, moving power away from government agencies allows communities to play a critical role in decision making and leads to communities becoming highly invested in positive environmental outcomes (Forgie et al. 2001).

The degree to which CBCGs in the Manawatū collaborate with iwi was found to be variable. This reflects the findings of a previous study by Peters et al. (2015b), which found that only 41% of CBCGs had received cultural advice from iwi, and 22.3% of CBCGs wanted an increase in cultural advice by iwi. They also found that there was limited on-ground involvement in CBCGs by iwi with only 4.4% of groups having iwi contribute to on-ground work. However, it is important to note that many iwi have their own CBCGs that they operate on top of their obligations to manage a range of conservation decisions within their jurisdiction and their many other roles and responsibilities.

Iwi are crucial partners for many CBCGs and it is important that conservation projects take traditional knowledge and cultural values into account, and consider environmental issues that are relevant to Māori (Forgie et al. 2001). Walker et al. (2024) found that Māori were more likely to attend whānau5, marae6, and tribal restoration events than events run by councils or other forms of restoration events. They conclude that cultural and community connection are important drivers for participation in CBC events, but found that these drivers are often under recognised.

An increased recognition of the importance of cultural and community connection and the common interests of Māori and the wider community would help to promote partnerships between CBCGs and iwi by encouraging collaboration to address local conservation issues, and work together sharing the responsibility of managing local conservation areas (Roberts et al. 1995; Taiepa et al. 1997; Forgie et al. 2001).

Community-based environmental monitoring

Only a small proportion of New Zealand CBCGs carry out community-based environmental monitoring where they collect data around changes in ecosystem health, and species abundance and distribution (Peters et al. 2015a, 2016). Community-based environmental monitoring has been found to be constrained by the availability of willing volunteers, the scientific literacy of volunteers, and the need for some help with technical aspects (Peters et al. 2016). Some of the easier forms of monitoring tend to be more commonly carried out, including 5-min bird calls, and photo points (Peters et al. 2016). Five-min bird calls were one of the top forms of community-based environmental monitoring in Manawatū CBCGs, along with other simple monitoring including pest trapping and tunnels, rubbish collection, plant survival and growth, and water quality tests. Public awareness of a decline in freshwater health means that there tends to be an increased interest in water quality monitoring in CBCGs (Hughey et al. 2013; Peters et al. 2016). This is also the case in Manawatū CBCGs where there is a focus on the Manawatū river and its catchment. Another aspect of community-based environmental monitoring, which is common among New Zealand CBCGs, is bird monitoring (Parker 2008; Peters et al. 2016), bird counts, and health monitoring with these activities being also common within CBCGs in the Manawatū.

In order to achieve their conservation goals, many of CBCGs in Aotearoa New Zealand rely on funding from project partners that can include, government resource management agencies, NGOs, science organisations, iwi, and local businesses (Hardie-Boys 2010; Jones and McNamara 2014; Peters et al. 2015a, 2015b, 2016; Sullivan and Molles 2016). These project partners often require evidence of successful conservation outcomes. To obtain this evidence, CBCGs often need to carry out some form of monitoring to receive further funding (Jones and Kirk 2018). In previous studies, it was found that most data collected by CBCGs was used to help guide their environmental projects, and that their data was often aligned with the requirements of funders for applications and reporting back (Peters et al. 2015a, 2015b, 2016). Yet, it was also found that there is often no comprehensive planning or milestones to demonstrate successfulness or progress (Peters et al. 2015a; Galbraith et al. 2016). Sullivan and Molles (2016) argued that having planned community-based environmental monitoring for CBCGs would improve future projects and increase the likelihood of funding, as many funding agencies require proof of success. A high proportion of the CBCGs in the Manawatū carry out limited or no community-based environmental monitoring. Therefore, it would be beneficial to many of the CBCGs to carry out planned community-based environmental monitoring to track success and increase the chances of receiving funding for future conservation goals.

An increased awareness of the need for broader and longer term monitoring in Aotearoa New Zealand means there is a reliance on CBCGs to contribute to local, regional, and national conservation goals (Lee et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2015a; Sullivan and Molles 2016). CBCGs are able to collect more data than government agencies alone and can therefore supplement data collection (Peters et al. 2015a). Community-based environmental monitoring has been shown to improve ecological knowledge within a community, and encourage relationships between CBCG members, project partners and the wider community. However, research also suggests that in order for this to happen CBCG volunteers need increased support from government agencies to increase their ability to monitor their own projects (Peters et al. 2015b). In order to further increase community-based environmental monitoring, DOC and local councils have a critical role to play to ensure that CBCGs have the knowledge and skills to carry out conservation activities and environmental monitoring (Department of Conservation and Ministry for the Environment 2000); this could be achieved by an increase in training courses and education around local conservation issues. Without considerable advice and technical support, community-based environmental monitoring can be challenging for CBCGs to undertake effectively (Galbraith et al. 2016). Increasing community-based environmental monitoring has the potential to have a positive impact on both conservation goals and volunteer participation. Community-based environmental monitoring could be a constructive alternative for volunteers that are not physically able to participate in the more strenuous activities typically undertaken by CBCGs, and may provide a stimulating task for volunteers that are motivated by learning and prefer to avoid tasks that are repetitive and mundane such as weeding and planting. Another benefit of incorporating community-based environmental monitoring could be to attract another demographic of volunteers, such as secondary or tertiary science students for whom contributing to community-based environmental monitoring could provide a mutually beneficial opportunity.

Conclusion

This study examines the barriers to effective CBC and contributes to the understanding of the challenges associated with CBC volunteering, and the impact that volunteer motivations have on the continued participation of volunteers. In order for CBCGs to be successful, they must be able to recruit and retain volunteers. Our study suggests that social interaction is the most productive way to recruit new volunteers, while highlighting the value in utilising a variety of recruitment methods. While volunteer recruitment is crucial to growth, it is even more important to retain current volunteers. In order to achieve this, CBCG leaders and partners such as local councils and the DOC need to consider barriers to volunteering in the planning stages of conservation projects and programs. The two main barriers we found were time constraints and declining health. Some ways CBCG leaders and management can help mitigate these barriers includes clearly communicating time commitments ahead of time, being flexible and offering volunteers a range of commitment levels, providing a range of tasks (including non-physical options), supporting volunteers to change commitment levels, and attempting to recruit a diverse group of volunteers to reduce the impact of age-related health issues on volunteer retention. CBCGs should also encourage their volunteers to build relationships with each other, in order to reduce conflicts and volunteer dissatisfaction.

Building connections with local councils, NGOs, iwi, and other CBCGs is also important as they provide crucial support to help ensure successful and effective CBC. A collaborative approach creates a framework that encourages participation by supporting and empowering CBCGs, allows communities to work together on conservation initiatives, and can increase volunteer commitment (Forgie et al. 2001). There is also a need for increased recognition of the importance of Māori culture and interests to help promote collaboration with local iwi within CBC (Roberts et al. 1995; Taiepa et al. 1997; Forgie et al. 2001).

It was found that although some CBCGs carry out some monitoring including monitoring pest trapping and tunnels, rubbish collection, plant survival and growth, and water quality tests, in general, community-based environmental monitoring is currently limited in the Manawatū. It is important that local councils and the DOC encourage and support community-based environmental monitoring to provide the evidence of successful conservation outcomes that are needed to obtain and maintain funding, and to contribute to understanding and enhancing local and regional conservation outcomes. In order to increase community-based environmental monitoring, CBCGs need additional support from local and central government, including education, training programs and on the ground technical support to develop the knowledge and skills to carry out reliable community-based environmental monitoring. There is also scope for further networking and collaboration between CBCGs within and between regions to learn from each other and leverage the collective expertise of experienced volunteers and employees.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Author contributions

The primary author is Charlotte Sextus who collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Karen Hytten and Paul Perry are co-authors who supervised research and contributed to writing the manuscript; they also contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Environment Network Manawatu for helping to distribute our questionnaire, and to all the individuals who participated in our study.

References

Asah ST, Blahna DJ (2013) Practical implications of understanding the influence of motivations on commitment to voluntary urban conservation stewardship. Conservation Biology 27(4), 866-875.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Asah ST, Lenentine MM, Blahna DJ (2014) Benefits of urban landscape eco-volunteerism: mixed methods segmentation analysis and implications for volunteer retention. Landscape and Urban Planning 123, 108-113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bramston P, Pretty G, Zammit C (2011) Assessing environmental stewardship motivation. Environment and Behavior 43(6), 776-788.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bruyere B, Rappe S (2007) Identifying the motivations of environmental volunteers. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 50(4), 503-516.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bushway LJ, Dickinson JL, Stedman RC, Wagenet LP, Weinstein DA (2011) Benefits, motivations, and barriers related to environmental volunteerism for older adults: developing a research agenda. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 72(3), 189-206.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chen P-W, Chen L-K, Huang H-K, Loh C-H (2022) Productive aging by environmental volunteerism: a systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 98, 104563.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clary EG, Snyder M, Ridge RD, Copeland J, Stukas AA, Haugen J, Miene P (1998) Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: a functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74(6), 1516-1530.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Conrad CC, Hilchey KG (2011) A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: issues and opportunities. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 176(1), 273-291.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Craig J, Anderson S, Clout M, Creese B, Mitchell N, Ogden J, Roberts M, Ussher G (2000) Conservation issues in New Zealand. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31, 61-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crall AW, Jordan R, Holfelder K, Newman GJ, Graham J, Waller DM (2013) The impacts of an invasive species citizen science training program on participant attitudes, behavior, and science literacy. Public Understanding of Science 22(6), 745-764.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Department of Conservation (2023) About us. Available at https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/ [Verified October 2023]

Dickinson JL, Shirk J, Bonter D, Bonney R, Crain RL, Martin J, Phillips T, Purcell K (2012) The current state of citizen science as a tool for ecological research and public engagement. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10(6), 291-297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ding C, Schuett MA (2020) Predicting the commitment of volunteers’ environmental stewardship: does generativity play a role? Sustainability 12(17), 6802.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Environment Foundation (2018) Environment guide. In ‘Maori and Environmental Law’. Vol. 2021. Available at https://www.environmentguide.org.nz/overview/maori-and-environmental-law/

Environment Network Manawatū (2023) About Environment Network Manawatū. Available at https://enm.org.nz/about-environment-network-manawatu

Figure NZ Trust (2023) Farm types in the Manawatu District, New Zealand. Vol. 2023. Available at https://figure.nz/chart/rIwyvzqecliuvVqY-rTJz5CtqroZMpeE6

Forest and Bird (2023) About forest and bird. Available at https://www.forestandbird.org.nz/about-us

Frensley T, Crall A, Stern M, Jordan R, Gray S, Prysby M, Newman G, Hmelo-Silver C, Mellor D, Huang J (2017) Bridging the benefits of online and community supported citizen science: a case study on motivation and retention with conservation-oriented volunteers. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 2(1), 1-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Froelich K, McKee G, Rathge R (2011) Succession planning in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 22(1), 3-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Galbraith M, Bollard-Breen B, Towns DR (2016) The community-conserversation conundrum: is citizen science the answer? Land 5, 37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ganzevoort W, van den Born RJG (2020) Understanding citizens’ action for nature: the profile, motivations and experiences of Dutch nature volunteers. Journal for Nature Conservation 55, 125824.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gura T (2013) Citizen science: amateur experts. Nature 496(7444), 259-261.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Heimann A, Medvecky F (2022) Attitudes and motivations of New Zealand conservation volunteers. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 46(1), 3464.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Higgins O, Shackleton CM (2015) The benefits from and barriers to participation in civic environmental organisations in South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation 24(8), 2031-2046.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hobbs SJ, White PCL (2012) Motivations and barriers in relation to community participation in biodiversity recording. Journal for Nature Conservation 20(6), 364-373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hong S-I, Morrow-Howell N (2013) Increasing older adults’ benefits from institutional capacity of volunteer programs. Social Work Research 37(2), 99-108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Horizons Regional Council (2024a) Biodiversity. Vol. 2024. Available at https://www.horizons.govt.nz/managing-natural-resources/biodiversity-and-totara-reserve

Horizons Regional Council (2024b) Environmental education. Vol. 2024. Available at https://www.horizons.govt.nz/managing-natural-resources/environmental-education

Hvenegaard GT, Perkins R (2019) Motivations, commitment, and turnover of bluebird trail managers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 24(3), 250-266.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Johnson BL (2022) Pass the torch: leadership development and succession planning in nonprofit organizations. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing 27(4), e1770.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jones C, Kirk N (2018) Shared visions: can community conservation projects’ outcomes inform on their likely contributions to national biodiversity goals? New Zealand Journal of Ecology 42(2), 116-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jones C, McNamara L (2014) Usefulness of two bioeconomic frameworks for evaluation of community-initiated species conservation projects. Wildlife Research 41, 106-116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Land Air Water Aotearoa (2024) Manawatu. Available at https://www.lawa.org.nz/explore-data/manawatū-whanganui-region/river-quality/manawatū/ [accessed April 2024]

Larson LR, Cooper CB, Futch S, Singh D, Shipley NJ, Dale K, LeBaron GS, Takekawa JY (2020) The diverse motivations of citizen scientists: does conservation emphasis grow as volunteer participation progresses? Biological Conservation 242, 108428.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Li H (2019) Leadership succession and the performance of nonprofit organizations: a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 29(3), 341-361.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liarakou G, Kostelou E, Gavrilakis C (2011) Environmental volunteers: factors influencing their involvement in environmental action. Environmental Education Research 17(5), 651-673.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Madsen SF, Ekelund F, Strange N, Schou JS (2021) Motivations of volunteers in Danish grazing organizations. Sustainability 13(15), 8163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McKinnon M (2015) Manawatū and Horowhenua region: population. Vol. 2024. Te Ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available at http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/manawatu-and-horowhenua-region/page-10

Measham TG, Barnett GB (2008) Environmental volunteering: motivations, modes and outcomes. Australian Geographer 39(4), 537-552.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moorfield JC (2024) Te Aka: Māori Dictionary. Available at https://maoridictionary.co.nz/

National Wetland Trust of New Zealand (2023) Manawatu estuary. Vol. 2023. Available at https://www.wetlandtrust.org.nz/get-involved/ramsar-wetlands/manawatu-estuary/

O’Brien L, Townsend M, Ebden M (2010) ‘Doing something positive’: volunteers’ experiences of the well-being benefits derived from practical conservation activities in nature. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 21(4), 525-545.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Orchard S (2019) Growing citizen science for conservation to support diverse project objectives and the motivations of volunteers. Pacific Conservation Biology 25, 342-344.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pagès M, Fischer A, van der Wal R (2018) The dynamics of volunteer motivations for engaging in the management of invasive plants: insights from a mixed-methods study on Scottish seabird islands. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61(5-6), 904-923.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parker KA (2008) Translocations: providing outcomes for wildlife, resource managers, scientists, and the human community. Restoration Ecology 16(2), 204-209.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Patrick R, Henderson-Wilson C, Ebden M (2022) Exploring the co-benefits of environmental volunteering for human and planetary health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 33, 57-67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Peters MA, Eames C, Hamilton D (2015a) The use and value of citizen science data in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 45(3), 151-160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peters MA, Hamilton DP, Eames CW (2015b) Action on the ground: a review of community environmental groups’ restoration objectives, activities and partnerships in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 39(2), 179-189.

| Google Scholar |

Peters MA, Hamilton D, Eames C, Innes J, Mason NWH (2016) The current state of community-based environmental monitoring in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 40(3), 279-288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pope J (2005) Volunteering in Victoria over 2004. Australian Journal on Volunteering 10(2), 29-34.

| Google Scholar |

Roberts M, Norman W, Minhinnick N, Wihongi D, Kirkwood C (1995) Kaitiakitanga: Maori perspectives on conservation. Pacific Conservation Biology 2(1), 7-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ryan RL, Kaplan R, Grese RE (2001) Predicting volunteer commitment in environmental stewardship programmes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 44(5), 629-648.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schild R (2018) Fostering environmental citizenship: the motivations and outcomes of civic recreation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61(5-6), 924-949.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sextus CP, Hytten KF, Perry P (2024a) A systematic review of environmental volunteer motivations. Society & Natural Resources 37, 1591-1608.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sextus CP, Hytten KF, Perry P (2024b) Volunteer commitment and longevity in community-based conservation in Aotearoa New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online 1-21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stats NZ (2018a) 2018 Census place summaries, Manawatu district. Vol. 2023. Available at https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/manawatu-district

Stats NZ (2018b) Palmerston North City. Vol. 2023. Available at https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/palmerston-north-city

Sullivan JJ, Molles LE (2016) Biodiversity monitoring by community-based restoration groups in New Zealand. Ecological Management & Restoration 17(3), 210-217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Taiepa T, Lyver P, Horsley P, Davis J, Brag M, Moller H (1997) Co-management of New Zealand’s conservation estate by Maori and Pakeha: a review. Environmental Conservation 24(3), 236-250.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Takase Y, Hadi AA, Furuya K (2019) The relationship between volunteer motivations and variation in frequency of participation in conservation activities. Environmental Management 63(1), 32-45.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thomas JL, Cullen M, O’Leary D, Wilson C, Fitzsimons JA (2021) Characteristics and preferences of volunteers in a large national bird conservation program in Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 22(1), 100-105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Walker E, Jowett T, Whaanga H, Wehi PM (2024) Cultural stewardship in urban spaces: Reviving Indigenous knowledge for the restoration of nature. People and Nature 6, 1696-1712.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zuo A, Wheeler SA, Edwards J (2016) Understanding and encouraging greater nature engagement in Australia: results from a national survey. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 59(6), 1107-1125.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Footnotes

1 Iwi are an ‘extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people, nationality’ and ‘often refers to a large group of people descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory’ (Moorfield 2024).

2 The Environment Network Manawatū is a network of member groups that supports and encourages environmental initiatives in the Manawatū, in areas ranging from sustainable living to wildlife conservation (Environment Network Manawatū 2023).

3 Forest and Bird is the peak NGO advocating for nature conservation in New Zealand (Forest and Bird 2023).

4 Rohe is the Maori word for boundary, district, region, territory, area, border (of land) (Moorfield 2024).

5 Whānau is the Māori word for extended family, family group, a familiar term of address to a number of people – the primary economic unit of traditional Māori society (Moorfield 2024).

6 Marae is the Māori word for courtyard – the open area in front of the wharenui, where formal greetings and discussions take place. Often also used to include the complex of buildings around the marae (Moorfield 2024).