Introduction to the special issue of The Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia

A. J. M. Hopkins A , G. T. Smith B and D. A. Saunders C *

C *

A

B

C

Abstract

This paper introduces the special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology devoted to the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on the south coast of Western Australia.

This paper provides the background to the special issue.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was gazetted in 1967 for the conservation of the native biota, including two species; the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) and Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo (Potorous gilbertii), both believed extinct for over 100 years before being rediscovered on the Reserve. The Reserve is 4774.7 ha in area, with wetlands, heathlands, granite outcrops, sand dunes, beaches, cliffs, and islands. Since it was established, mean annual rainfall has decreased by 16.8%, mean annual maximum temperature has increased by 0.2°C, and mean annual minimum temperature has increased by 0.7°C.

The paper poses the question: what do the changes of drier winters, hotter summers, and more extreme weather events mean for managers of conservation areas such as Two Peoples Bay?

Changing climate will pose problems for the managers of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in ensuring the conservation of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo.

Keywords: Atrichornis clamosus, climate change, Djimaalup Ngilgaitch, extreme weather events, Gilbert’s potoroo, noisy scrub-bird, Potorous gilbertii.

Introduction

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is one of the most important nature conservation areas along the south coast of Western Australia. Its importance is based on two factors. First, it contains remnant populations of rare fauna and flora, of which the best known are the noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) or Djimaalap (Noongar names are from Knapp et al. 2024) and Gilbert’s potoroo (Potorous gilbertii) or Ngilgaitch (Fig. 1). Both species were believed to be extinct for over 100 years before being rediscovered on the Reserve. Second, it is a place where considerable research effort has been concentrated since its gazettal as a nature reserve in 1967; therefore, it has the potential to serve as a model for development of management practices for the region and beyond.

Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (top) and Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo (bottom). Both species were believed extinct for over 100 years before being rediscovered at Two Peoples Bay (photographs: Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird A. Danks; Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo S. D. Hopper).

This special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve had its genesis in 1981 when the Western Australian Department of Fisheries and Wildlife decided to produce a management plan for the Reserve. There was a need to prepare a comprehensive background document to provide a basis for planning and, at the same time, it was recognised that such a document would encourage further research. It was envisioned this would also facilitate production of educational and interpretive material, and thereby engender a greater interest in, and understanding of, the nature conservation issues of the Reserve in particular, and of Western Australia in general.

Some of the papers to be published in the proposed comprehensive document resulted from studies that Mr Angas Hopkins (Western Australian Department of Fisheries and Wildlife) and Dr Graeme Smith (CSIRO Department of Wildlife Research) began in the 1970s. Because these studies were limited in scope and because of the need to prepare a comprehensive management plan, Hopkins and Smith solicited contributions from others who had relevant knowledge of other environmental aspects of Two Peoples Bay. Their idea was to publish the compilation of papers as a special bulletin of CALMScience, the journal of the Department of Conservation and Land Management, the successor agency to the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. By 1991, a volume of 23 papers had been collated, covering a range of subjects from the history of the establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, its geology, landforms and soils, climate, biota, fire history, invasion by Phytophthora cinnamomi (jarrah dieback pathogen), and management. Each paper was peer-reviewed and revised in the light of reviewers’ comments. The papers proceeded to layout in July 1991 as a mock-up for publication. For some reason, the project went no further. Smith died in 1999 and Hopkins in 2016 without seeing their collection of papers to publication.

In early November 2023, co-author of the present article D. A. Saunders (DAS) published a paper that included data Graeme Smith had collected for him; the paper was dedicated to Smith (Saunders 2023). While preparing the paper, DAS wondered about Smith’s Two Peoples Bay legacy and tried to find out if any copies of the edited, unpublished volume on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay existed. It turned out that the only extant, relatively complete copy was a printed version of the mock-up of the publication, dated July 1991, that Hopkins had sent to Smith on 21 June 1993, together with a memorandum that stated: ‘Please find enclosed your copy of the mock-up of the publication. The thing is now going through the final stages of the publication approvals process… and the production is being costed. Don’t hold your breath but at least this represents an advance.’ This copy was part of Smith’s papers in an archive held by his daughters Katy Macknay and Lizzie Smith, however, the copy lacked most of the illustrations and tables.

Much has changed in the more than three decades since Hopkins and Smith’s decision to collate a volume on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) was established in 1985, incorporating the Wildlife branch of the former Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. CALM’s role was to manage Western Australia’s nature conservation lands and waters. In 1987, the vesting of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was formally transferred to the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority. More importantly for the Reserve, new discoveries were made about the biota as more research workers became involved in the area. For example, Alan Danks, Reserves Management Officer, who commenced duty in 1985, added considerably to the area’s bird list, and Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo, Australia’s rarest marsupial, was rediscovered at Two Peoples Bay by Elizabeth Sinclair in 1994 (Sinclair et al. 1996). Management issues changed as number of visitors to the Reserve continued to increase and the full impact of jarrah dieback on the vegetation and its associated biota became apparent.

The challenge of seeing Hopkins and Smith’s legacy to publication in Pacific Conservation Biology was to engage with the original contributors to ascertain if they were willing to revise the papers they had in press for over three decades, to reflect the changes that had taken place since their paper was accepted for publication. This was made more challenging by the fact that both editors were dead, as were many of the contributors. In fact, of the 22 contributors to the mocked-up version of the 1991 CALMScience Bulletin, 11 were either dead or uncontactable. Fortunately, DAS’ request to the 10 original contributors who could be contacted was met with enthusiasm and encouragement. In addition, a number of other people, with knowledge of the papers where none of the original contributors was able to revise them, agreed to act as co-authors to bring the papers up to date and publish them.

There is one paper in this special issue that was not to be included in the original bulletin. Chatfield and Saunders’ (2024) account of the history and establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve commenced with Captain Vancouver’s mapping of Western Australia’s south coast and his naming of Mt Gardner in 1791. As was common in the 1980s, the role of Aboriginal peoples in land management was ignored or discounted. Chatfield and Saunders’ only mention of Aboriginal peoples was in relation to their interaction with sealers and whalers. Of course, Noongar people have thousands of years of residence on the south coast of Western Australia, and the history of their association with country is critical to the story of Two Peoples Bay. Fortunately, Knapp et al. (2024) were able to fill this gap in the history of Two Peoples Bay and their Noongar names are used in this special issue.

Status, location, and size

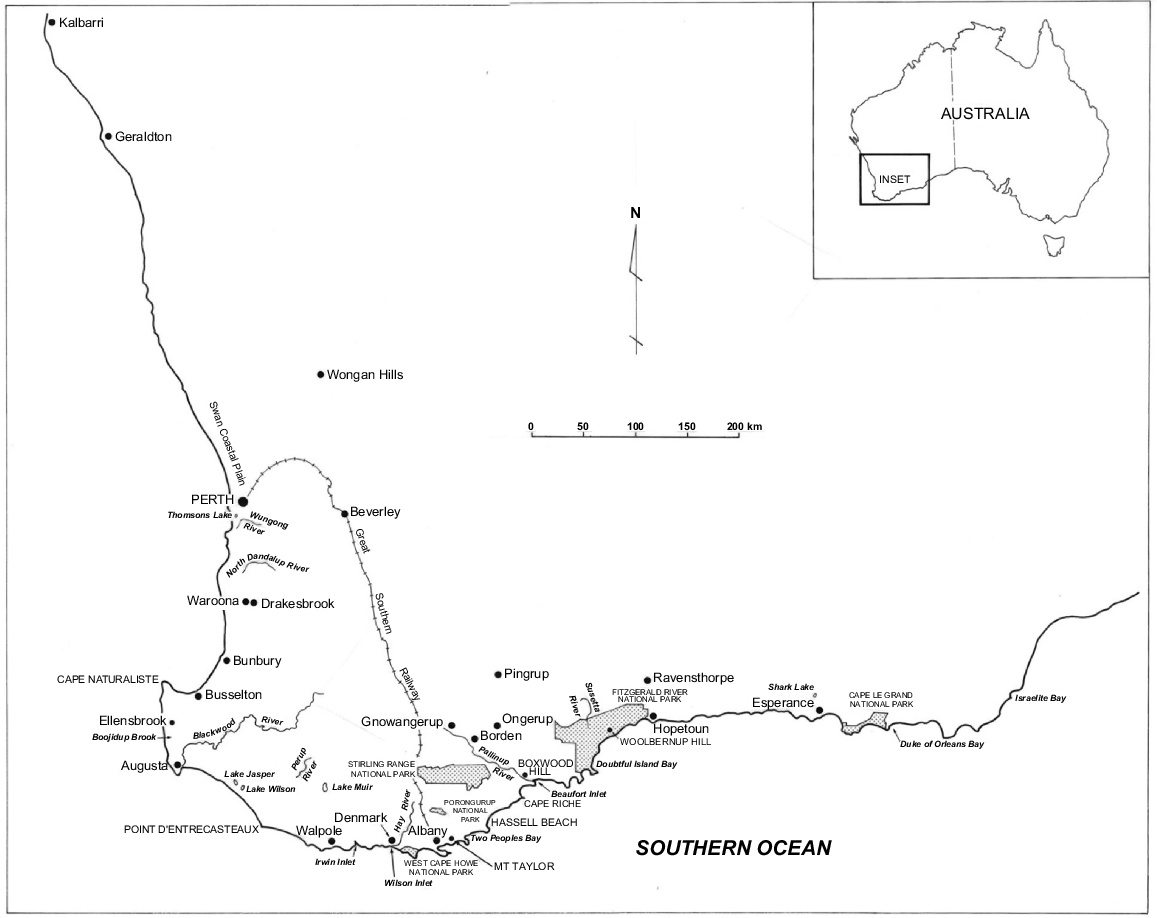

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is a Class A Reserve (No A27956) for the Conservation of Flora and Fauna. It is vested in the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority, the authority established under the Conservation and Land Management Act 1984 (WA). The Reserve is located between 118.05° and 118.22° and −34.93° and −35.03°, on the south coast of Western Australian, 27 km east of Albany (Fig. 2). It is within the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ South Coast Region, which is administered from Albany.

Map of southwestern Australia showing locations referred to in this special issue of the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

The Reserve has an area of 4774.7 ha to the low water mark. This is made up of two portions on the mainland (surrounding Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake, Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, and Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, and surrounding Miialyiin/Angove Lake and part of Angove River) and four adjacent islands (Coffin Island, Inner Island, Boyanbelokup/Rock Dunder, and Black Rock; Fig. 3). These range in size from Coffin Island’s ~28 ha to Black Rock’s ~3 ha. The main section of the Reserve, of about 4685 ha, takes in ~25 km of coastline west from Two Peoples Bay around Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland almost to Nornarup/Nanarup on the south coast (Fig. 3). The smaller mainland section (~89 ha) comprising Miialyiin/Angove Lake, its northern margin and part of the Angove River, is located about 2 km north of the main section of the Reserve (Fig. 3). The Miialyiin/Angove Lake section has legal access through Reserve 13802 (Albany Water Supply Catchment Area – Angove River), but practical access is gained through farming land, by vehicle through the farming property Tandara, or by foot from the Two Peoples Bay beach. Access to the islands by boat is difficult because of the lack of easy landing areas and the normally heavy swells.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (outlined in red) and locations mentioned in the text. Noongar names are from Knapp et al. (2024).

Climate

The climate patterns experienced within Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve have important influences on all its abiotic and biotic components. For example, climate affects rates of weathering of rocks and soil formation, as well as factors such as erosion, the distribution of plants, animals, and pathogens over the landscape and their seasonal behaviour, and processes such as the behaviour of fire.

Albany, 27 km west-south-west of Two Peoples Bay and also on the coast (Fig. 2), is the Bureau of Meteorology’s weather station (Albany townsite BOM # 009500, www.bom.gov.au) closest to Two Peoples Bay. It has data on daily rainfall from 1877, and on daily maximum and minimum temperatures from 1880. Data from Albany townsite as a surrogate for Two Peoples Bay, demonstrate that the bay has a mild Mediterranean-type climate of warm, dry summers (December–February) and cool, wet winters (June–August) (Tables 1 and 2). Long-term data show monthly mean summer maximum temperatures between 21.8 and 22.9°C and monthly mean winter minimum temperatures between 8.3 and 9.2°C (Table 1). Over the long term (1877–2023), mean annual rainfall was 922.2 mm, with 43% of rain falling in winter (Table 2).

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean max temp (ºC) | ||||||||||||||

| 1955 | 23.1 | 22.4 | 32.2 | 19.9 | 17.1 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 20.2 | 21.9 | 19.0 | |

| 1956 | 25.4 | 23.6 | 23.7 | 19.4 | 17.5 | 14.7 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 17.2 | 17.6 | 20.9 | 22.5 | 19.3 | |

| 1957 | 24.8 | 24.2 | 22.8 | 20.5 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 14.9 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 22.0 | 22.9 | 20.2 | |

| 1958 | 25.2 | 24.0 | 23.1 | 22.1 | 18.6 | 16.9 | 14.3 | 16.4 | 15.6 | 17.9 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 19.8 | |

| 1959 | 24.3 | 22.5 | 24.5 | 21.8 | 19.1 | 17.6 | 17.1 | 18.1 | 16.9 | 19.7 | 19.3 | 20.0 | 20.1 | |

| 1960 | 21.8 | 22.8 | 20.7 | 18.5 | 17.3 | 16.2 | 14.1 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 19.7 | 19.3 | 22.0 | 18.8 | |

| 1961 | 24.3 | 25.7 | 24.8 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 16.9 | 15.5 | 16.1 | 18.6 | 19.3 | 21.5 | 21.6 | 20.3 | |

| 1962 | 23.3 | 23.4 | 22.6 | 22.1 | 19.2 | 17.8 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 21.7 | 22.2 | 20.1 | |

| 1963 | 22.8 | 23.2 | 23.2 | 21.4 | 19.2 | 16.6 | 15.3 | 16.7 | 17.7 | 20.8 | 20.9 | 23.3 | 20.1 | |

| 1964 | 23.0 | 22.5 | 23.4 | 19.6 | 18.7 | 17.5 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 16.6 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 19.1 | |

| Mean 1955–1964 | 23.8 | 23.4 | 24.1 | 20.5 | 18.6 | 16.6 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 17.1 | 18.7 | 20.8 | 21.9 | 19.7 | |

| 2014 | 23.8 | 22.5 | 22.4 | 21.4 | 19.3 | 18.1 | 16.7 | 18.6 | 19.4 | 19.2 | 21.0 | 20.9 | 20.3 | |

| 2015 | 23.4 | 23.7 | 22.5 | 21.2 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 18.9 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 21.5 | 20.3 | |

| 2016 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 22.6 | 20.6 | 18.6 | 16.7 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 15.9 | 18.0 | 20.6 | 20.8 | 19.4 | |

| 2017 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 21.8 | 20.1 | 19.4 | 19.0 | 15.9 | 16.7 | 17.5 | 19.1 | 20.6 | 21.5 | 19.7 | |

| 2018 | 22.4 | 23.0 | 22.4 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 17.4 | 17.0 | 16.2 | 17.0 | 19.0 | 18.7 | 21.1 | 19.7 | |

| 2019 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 18.7 | 17.6 | 16.8 | 17.9 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 23.5 | 19.9 | |

| 2020 | 22.2 | 23.4 | 23.1 | 21.2 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 17.3 | 16.9 | 18.1 | 19.4 | 20.5 | 21.1 | 20.1 | |

| 2021 | 22.8 | 21.9 | 23.6 | 21.1 | 19.7 | 17.5 | 16.0 | 17.2 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 18.8 | 21.3 | 19.7 | |

| 2022 | 22.4 | 23.6 | 22.6 | 21.4 | 19.0 | 17.6 | 17.2 | 15.9 | 17.8 | 17.7 | 19.1 | 21.1 | 19.6 | |

| 2023 | 22.8 | 23.5 | 22.6 | 20.7 | 19.2 | 14.2 | 17.3 | 18.0 | 19.6 | 20.4 | 22.4 | 21.1 | 20.1 | |

| Mean 2014–2023 | 22.7 | 22.9 | 22.5 | 21.0 | 19.3 | 17.6 | 16.7 | 17.1 | 18.2 | 19.1 | 20.2 | 21.4 | 19.9 | |

| Difference 1955–1964 and 2014–2023 | −1.1 | −0.5 | −1.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Mean 1880–2023 | 22.8 | 22.9 | 22.3 | 20.9 | 18.7 | 16.7 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 20.3 | 21.8 | 19.5 | |

| Mean min temp (ºC) | ||||||||||||||

| 1955 | 15.9 | 16.7 | 15.3 | 12.7 | 11.2 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 11.8 | |

| 1956 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 15.6 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 11.7 | |

| 1957 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 15.0 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 10.6 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 14.3 | 12.2 | |

| 1958 | 17.0 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 13.6 | 12.1 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 13.2 | 15.5 | 12.5 | |

| 1959 | 15.7 | 16.9 | 16.6 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 13.2 | 12.6 | |

| 1960 | 14.2 | 15.9 | 13.5 | 11.9 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 14.5 | 11.4 | |

| 1961 | 16.7 | 17.6 | 16.2 | 12.9 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 13.0 | 15.1 | 12.7 | |

| 1962 | 17.1 | 15.9 | 14.8 | 14.2 | 12.1 | 10.8 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 15.3 | 12.5 | |

| 1963 | 16.0 | 16.3 | 16.9 | 13.1 | 12.1 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 15.8 | 12.7 | |

| 1964 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 14.8 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 13.9 | 11.8 | |

| Mean 1955–1964 | 16.1 | 16.4 | 15.5 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 12.2 | |

| 2014 | 16.7 | 16.8 | 16.2 | 14 | 12.9 | 11.2 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 11 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 13.2 | |

| 2015 | 17.1 | 18.0 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 13.2 | |

| 2016 | 17.7 | 16.9 | 16.6 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 12.6 | 14.2 | 12.6 | |

| 2017 | 14.6 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 14.2 | 12.1 | 9.3 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 14.8 | 12.5 | |

| 2018 | 16.6 | 17.0 | 16.6 | 14.1 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 14.3 | 12.7 | |

| 2019 | 15.3 | 17.0 | 15.8 | 12.9 | 10.8 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 15.5 | 12.7 | |

| 2020 | 15.9 | 17.8 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 12.1 | 12.7 | 15.0 | 12.8 | |

| 2021 | 16.4 | 16.5 | 16.6 | 14.6 | 12.9 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 14.9 | 12.9 | |

| 2022 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 14.0 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 15.1 | 13.0 | |

| 2023 | 16.5 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 16.1 | 13.1 | |

| Mean 2014–2023 | 16.4 | 17.0 | 16.3 | 13.9 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 13.4 | 15.0 | 12.9 | |

| Difference 1955–1964 and 2014–2023 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| Mean 1880–2023 | 15.3 | 15.6 | 14.9 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 12.5 | 14.1 | 11.8 | |

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 33.9 | 6.7 | 135.8 | 72.4 | 108.2 | 77.9 | 209.4 | 72.4 | 79.1 | 35.9 | 20.6 | 83.9 | 936.2 | |

| 1961 | 29.2 | 34.3 | 30.3 | 233.9 | 69.3 | 115.8 | 157.7 | 107.8 | 82.4 | 67.9 | 30.8 | 20.2 | 979.6 | |

| 1962 | 2.9 | 22.5 | 23.2 | 42.4 | 117.2 | 156.5 | 186.0 | 127.0 | 102.7 | 114.8 | 156.5 | 29.2 | 1082.9 | |

| 1963 | 33.3 | 22.8 | 45.9 | 55.2 | 271.0 | 124.1 | 205.2 | 116.1 | 84.5 | 70.3 | 31.7 | 13.8 | 1073.9 | |

| 1964 | 21.2 | 20.2 | 18.3 | 64.7 | 83.0 | 149.0 | 252.8 | 118.8 | 86.7 | 130.9 | 32.7 | 28.6 | 1006.9 | |

| 1965 | 28.5 | 15.0 | 40.5 | 39.2 | 118.6 | 119.4 | 79.6 | 167.0 | 80.0 | 110.2 | 75.5 | 82.7 | 956.2 | |

| 1966 | 13.5 | 11.8 | 23.0 | 73.8 | 123.8 | 171.2 | 141.3 | 120.9 | 172.2 | 90.9 | 24.9 | 40.2 | 1007.6 | |

| 1967 | 4.3 | 68.2 | 77.1 | 63.5 | 144.1 | 124.3 | 224.3 | 142.7 | 50.0 | 64.9 | 39.5 | 46.1 | 1049.0 | |

| 1968 | 40.6 | 18.3 | 80.7 | 116.1 | 58.6 | 127.3 | 114.8 | 136.6 | 151.2 | 78.0 | 29.0 | 13.1 | 964.3 | |

| 1969 | 9.8 | 3.4 | 27.7 | 83.3 | 52.9 | 130.9 | 103.7 | 96.4 | 52.5 | 47.4 | 33.2 | 11.5 | 652.7 | |

| Mean 1960–1969 | 21.7 | 22.3 | 50.3 | 84.5 | 114.7 | 129.6 | 167.5 | 120.6 | 94.1 | 81.1 | 47.4 | 36.9 | 970.9 | |

| 2014 | 3.2 | 7.0 | 21.2 | 33.0 | 87.3 | 77.8 | 121.0 | 59.8 | 67.7 | 115.1 | 44.5 | 11.0 | 648.6 | |

| 2015 | 5.4 | 20.9 | 35.6 | 77.8 | 57.7 | 53.2 | 89.4 | 101.2 | 52.9 | 59.5 | 17.1 | 50.0 | 620.5 | |

| 2016 | 73.8 | 21.7 | 44.2 | 94.6 | 97.9 | 120.3 | 122.6 | 117.1 | 102.8 | 62.8 | 22.6 | 34.1 | 914.5 | |

| 2017 | 3.6 | 52.2 | 45.8 | 51.3 | 67.0 | 66.2 | 151.9 | 166.6 | 150.0 | 54.2 | 12.7 | 51.0 | 872.5 | |

| 2018 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 18.6 | 54.2 | 39.4 | 83.2 | 164.6 | 147.8 | 65.3 | 60.4 | 32.8 | 22.4 | 711.0 | |

| 2019 | 14.6 | 1.1 | 42.1 | 51.2 | 31.0 | 102.2 | 135.8 | 119.1 | 43.2 | 56.4 | 48.0 | 4.0 | 648.7 | |

| 2020 | 11.8 | 14.4 | 40.6 | 38.8 | 128.1 | 100.4 | 121.4 | 198.9 | 111.2 | 28.3 | 85.4 | 24.4 | 903.7 | |

| 2021 | 18.2 | 46.8 | 28.7 | 117.1 | 181.3 | 113.6 | 214.9 | 118.8 | 115.0 | 110.0 | 28.4 | 12.0 | 1104.8 | |

| 2022 | 5.2 | 10.8 | 38.4 | 94.6 | 67.7 | 89.8 | 96.2 | 161.7 | 48.9 | 118.3 | 58.9 | 6.9 | 797.4 | |

| 2023 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 31.3 | 138.4 | 49.7 | 295.6 | 108.5 | 81.8 | 70.0 | 23.2 | 40.6 | 4.1 | 853.1 | |

| Mean 2014–2023 | 15.9 | 18.4 | 34.7 | 75.1 | 80.7 | 110.2 | 132.6 | 127.3 | 82.7 | 68.8 | 39.1 | 22.0 | 807.5 | |

| Difference 1960–1969 and 2014–2023 | −5.8 | −3.9 | −15.6 | −9.4 | −34.0 | −19.4 | −34.9 | 6.7 | −11.4 | −12.3 | −8.3 | −14.9 | −163.4 | |

| % change | −26.7 | −17.5 | −31.0 | −11.1 | −29.6 | −15.0 | −20.8 | 5.6 | −12.1 | −15.2 | −17.5 | −40.3 | −16.8 | |

| Mean 1877–2023 | 23.6 | 22.4 | 38.2 | 69.3 | 114.5 | 131.8 | 142.5 | 126.6 | 100.9 | 78.0 | 44.8 | 29.6 | 922.2 |

However, over the period leading to the gazettal of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in the 1960s and the present, there have been changes in the region’s temperatures and rainfall. Comparing monthly data on maximum and minimum temperatures for the decade 1955 to 1964 with those from 2014 to 2023 indicates the annual mean maximum temperature increased by 0.2°C, although not all months recorded an increase (Table 1). Mean annual minimum temperature increased by 0.7°C, with all months showing increases since the earlier period. In line with predictions of Charles et al. (2010), annual rainfall declined between 1960–1969 and 2014–2023, demonstrating a 163.4 mm difference between the two decades, a 16.8% decline (Table 2), with all months indicating a decline. The decline was greatest in the warmest months, December to March inclusive. There were records missing for temperatures at Albany in the period 1965–1969 and so data for the period 1955–1964 were used.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is part of the coastal zone and therefore at the interface between land, ocean, and atmosphere. It is a dynamic environment and, over time, movement of materials by wind has been a major factor modelling the area’s landscape (P. A. Hesp, unpubl. data; W. M. McArthur, G. A. Bartle, K. Evans, unpubl. data; P. E. Playford, I. Tyler, unpubl. data). Wind is still having a significant effect in redistributing detritus in the Reserve. Wind also influences other management considerations, such as provision of access to beaches and other locations, the orientation of tracks and firebreaks, in relation to fire behaviour and management, and in the spread of Phytophthora cinnamomi (Hart et al. 2024).

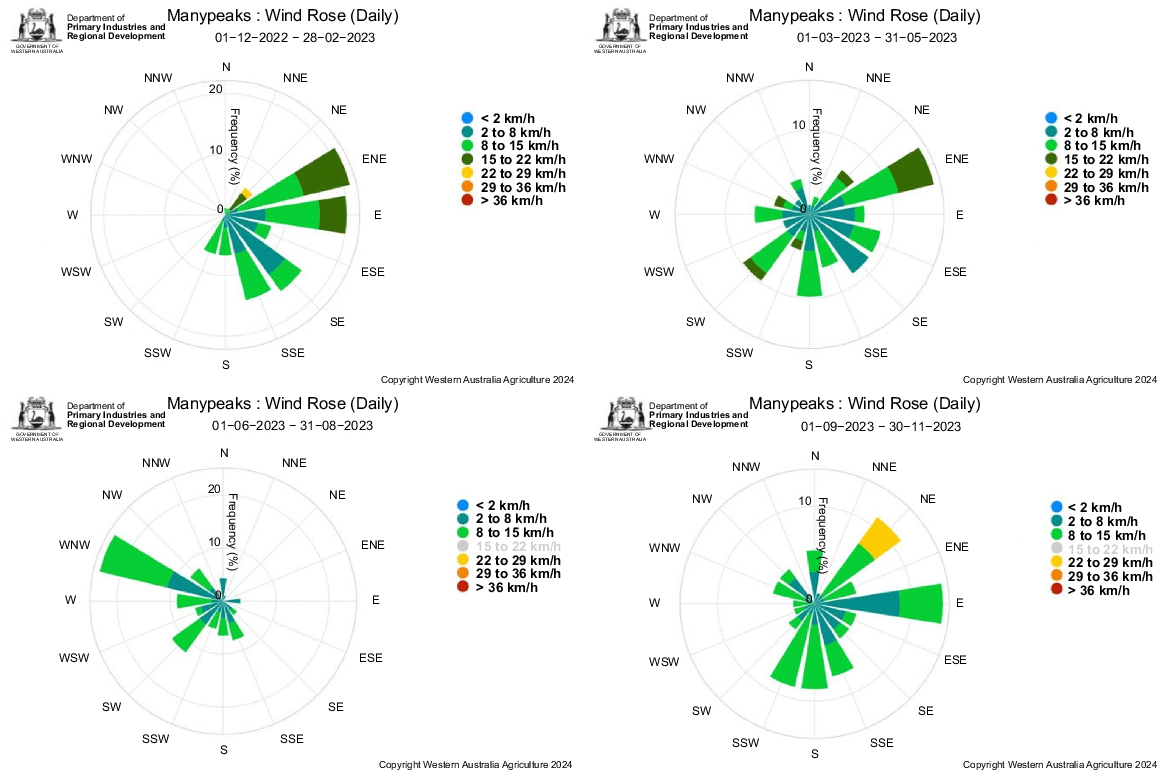

The nearest wind recording station is on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, on the coast, about 12 km north-east of Two Peoples Bay (https://weather.agric.wa.gov.au/station/MP) with data from 2010. Although conditions on the Reserve would not be identical to those on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, the wind pattern may be similar. Wind is expressed by four independent parameters; direction, speed, frequency, and duration. Wind direction, speed, and frequency are shown for the Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks station for December 2022–February 2023, March–May 2023, June–August 2023, and September–November 2023 representing summer, autumn, winter, and spring respectively (Fig. 4). Wind speed required to move loose sand varies with the nature of the surface and the atmospheric conditions, but it can be assumed that under conditions on the Reserve, any wind of 20 km/h or higher may move sand grains. The power of wind in sand movement increases as the cube of the speed. This has importance because, apart from the high speeds which may be recorded, there are sometimes strong gusts. These may be of short duration, but may initiate sand movement or cause structural damage to vegetation.

Monthly mean wind speed, direction, and frequency at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks (as a surrogate for Two Peoples Bay) for: summer (December–February); autumn (March–May); winter (June–August); and spring (September–November).

Using data from Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks for 2023 (Fig. 4), in summer, south-easterly winds predominate, at high speeds for some of the day. These winds have influence on sand movement in the east and south-facing bays. In autumn, the pattern changes with easterlies and southerly winds. In winter, westerly winds dominate, and in spring southerly and easterly wind dominate (https://weather.agric.wa.gov.au/station/MP; Fig. 4).

In addition to the changes in rainfall and temperatures, the biota will be affected by more extreme climatic events (Hennessy et al. 2008) such as the one day of extreme heat on Western Australia’s south coast in early January 2010. On 5 January 2010, the minimum and maximum temperatures at Hopetoun on the coast, about 180 km north-east of Two Peoples Bay, were 17.8°C−26.4°C, on 6 January 17.1°C−48.0°C, and 7 January 19.1°C−24.3°C. That one day of extreme heat, when the maximum temperature was nearly twice that of the day before, is known to have killed many species of birds (Fig. 5), including 145 endangered Carnaby’s cockatoos (Zanda latirostris) at Hopetoun and another 63 at Munglinup, 75 km east of Hopetoun (Saunders et al. 2011).

Some of the birds killed at Munglinup, Western Australia, as a result of one day of extreme heat on 6 January 2010. Upper photograph shows: (top row) three Carnaby’s cockatoos, two magpie-larks (Grallina cyanoleuca), and two galahs (Eolophus roseicapilla); and (bottom row) one nankeen kestrel (Falco cenchroides), four yellow-throated miners (Manorina flavigula), and six regent parrots (Polytelis anthopeplus). Bottom photograph shows some of the 63 Carnaby’s cockatoos killed (photographer unknown).

Major storms

During the 32 years of recorded weather events at Two Peoples Bay there have been three major storms impacting on the environment. The first was Cyclone Alby on the night of 4 April 1978. Although the north to south-westerly gale of this severe 7.5 h storm dumped tonnes of weed onto the beach and scoured the frontal dunes it was not from a direction that could cause maximum foreshore damage.

On 2–4 August 1984, an extremely severe storm wreaked considerable damage along the south coast, especially in the Albany District. The storm’s severity can be gauged by local people referring to it as ‘The Hundred Year Storm’. Large Norfolk Island pines (Araucaria heterophylla) were washed out of the ground at Albany’s Middleton Beach and beachcombers picked up live crayfish among hundreds of other marine animals that had been washed in from offshore reefs. At Two Peoples Bay, the south-easterly swell drove almost directly into the bay, bombarded the beaches overnight and continued for about 50 hours.

When relieving Reserve Officer Alan Danks looked along the bay on the morning of August 3, the beach had virtually disappeared and, out in the bay, the wave action had torn big gaps in the sea grass beds (an estimated 25% from the bay’s sandy bottom). By the time the storm was over, the beach along the southern quarter of the bay was clogged with torn and uprooted sea grass to a depth of about 3 m. This ‘weed rack’ banked up the water of Gardner Creek and created a spongy morass that prevented any access to the bay (A. Danks, pers. comm.). In his later report Reserve Officer Folley stated ‘the entire beach, fore dune and half of the vegetated (stable) dune were eroded’. Of the pocket beaches to the south of the main beach, many of the stable slopes had been eroded and, at Naarup/Waterfall Beach (Fig. 3), virtually all the sand had been swept out to sea (A. Danks, pers. comm.). The fringing woodland and swamp near the tidal pool that had been home to a Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird since 1982, was destroyed by wave action and salt water, which had swept over the rocks and across the pool (G. L. Folley, in litt.).

Another severe south-easterly storm occurred in late June 2005 when almost 200 mm of rain for the month was recorded at Two Peoples Bay. Erosion of the beach and foredunes disclosed a number of large, calcified whale bones from the mid-19th century whaling days. The weed rack from this storm was about 2 m deep.

What do the changes of drier winters, hotter summers, and more extreme weather events mean for managers of conservation areas such as Two Peoples Bay?

General description of the Nature Reserve

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve incorporates a wide variety of habitats; these include the coastal areas and islands already mentioned and many different terrestrial environment types (Figs 3 and 6).

Two Peoples Bay looking north from Cape Vancouver to Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, Coffin Island, and Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, 14 December 2016 (photograph S. D. Hopper).

Two Peoples Bay is flanked by rocky headlands and backed by a 5 km long, crescent-shaped, fine sandy beach. Behind the beach are well-vegetated sand dunes up to 10 m high. There are two smaller, but equally attractive, sandy beaches south-east of Yaalup/South Point; Little Beach, and Naarup/Waterfall Beach (Fig. 3). The remainder of the shoreline of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland is mainly steeply sloping, bare exposures of granite. Along the southern coastline to Rocky Point there is a 50 m high limestone cliff with a gentle landward slope and a steep scarp to seaward. At the foot of the scarp are the remnants of an old wave-cut platform and then a wide intertidal reef (Sinker Reef). To the west of Rocky Point and all the way to Nornarup/Nanarup a sandy beach is backed by steep dunes of between 30 and 40 m in elevation.

The most conspicuous feature of the Reserve is Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Knapp et al. 2024), a conical hill 408 m in elevation (Fig. 7). The slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner have been deeply dissected to produce well-vegetated gullies, which form important habitat for noisy scrub-birds. This south-eastern portion of the Reserve is referred to as the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland (Fig. 3).

Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, 408 m high, with dwarf form of Mungee/Nuytsia floribunda in the foreground, 14 December 2016 (photograph S. D. Hopper).

An isthmus with heath communities and open wonil/peppermint/Agonis flexuosa woodland separates Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner from the remnants of the late-Tertiary to early-Pleistocene lateritic plateau which takes in most of the Tandara property. The lateritic plateau is well vegetated with jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata)/Allocasuarina fraseriana forest.

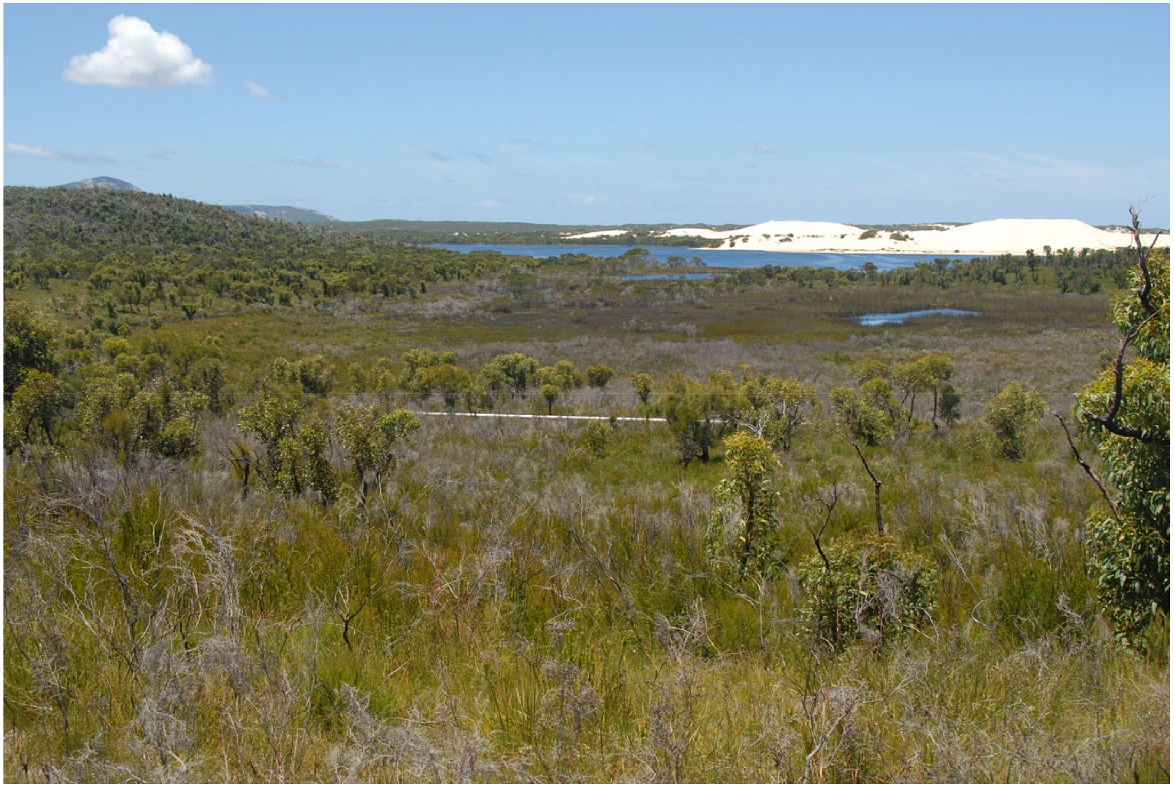

Below the lateritic plateau is the coastal plain of lithified and partially-lithified sands. Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, which is brackish, and Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake (Fig. 8) with fresh water, are major permanent waterbodies on this coastal plain. They are associated with low-lying terrain that is seasonally wet. Drainage of this area is restricted. Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake is fed by small streams and rivers, which include the Goodga River and Black Cat Creek. A series of waterways that flow for a large part of the year drain into Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake from the upstream Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake. Water may also seep through to Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake when there is no superficial flow. This second lake drains into the sea via Gardner Creek. However, the bar at the mouth of the creek is usually closed from late summer through to winter.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, with Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake in the foreground, Tyiurrtyaalup/sand dunes behind, and Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner on the horizon, 14 January 2014 (photograph S. D. Hopper).

As noted above, the Reserve includes the freshwater Miialyiin/Angove Lake and part of the Angove River, in an outlying block to the north of the main body of the reserve (Fig. 3). Drainage is to the south via a drain which enters Gardner Creek near the traffic bridge.

Immediately to the south of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake there is a large, mobile sand dune covering about 300 ha (Fig. 8). The area generally circumscribed by the dunes, Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lakes, the lateritic plateau and the sea cliff is referred to as the ‘between-the-lakes area’. To the west of the dune is the western boundary area. These two coastal plain areas are vegetated with a variety of woodland and shrubland types with a predominance of those dominated by Agonis flexuosa, Banksia littoralis, Adenanthos sericeus, and B. sessilis.

So far little attention has been given to the marine habitats adjacent to the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. However, the presence of the islands, reefs, and the variety of rocky and sandy shorelines suggests that they too might have important conservation values.

Significance of the Nature Reserve

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was created in 1967 following the rediscovery there in 1961 of the Djimaalup/noisy scrub-bird (Fig. 1). This bird is but one of four species of rare vertebrate fauna known to occur there. The others are Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo, Western whipbird (Psophodes nigrogularis) and Western bristlebird (Dasyornis longirostris). In addition, the reserve has a rich and interesting flora.

The Reserve has a significant place in the maritime exploration and early commercial history of Western Australia, as well as being a place of importance for nature conservation. The bay, with its sheltered anchorage and reliable supply of fresh water, was a popular stopping place in the 19th century for maritime explorers, and travellers, and for sealers and whalers (Chatfield and Saunders 2024). Later, the area became popular as a local recreation spot and has remained so, to this day.

The Reserve and its biota have been the subjects of extensive research by CSIRO, State Government agencies, academic institutions, and private individuals since 1961. Initially, much of the research focused on the noisy scrub-bird; however, other features of the Reserve have also received attention. The Reserve, and related research findings, and the various innovative management initiatives that have been implemented since the gazettal of the Reserve, have all generated considerable public interest at local (Fig. 9), national and international levels.

Dr Tony Friend talks about Ngilgaitch/Gilbert’s potoroo to University of Western Australia third year students in the unit Saving Endangered Species on 2 February 2017, 2 years after the 2015 fire at Little Beach, with the head of Boyankaatup on the hill above looking north at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks (photograph S. D. Hopper).

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve has long been considered the jewel in the conservation reserve system, principally because of the presence of the rare birds. The information compiled in this special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology clearly shows that the Reserve has many additional important cultural, social, and natural values. This information also permits the Reserve to become the model for the development of management theory and practices for the region and possibly the State.

Dedication

This special issue on the Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is dedicated to the memory of the many original contributors to the unpublished special bulletin of CALMScience who died before seeing their work updated and published in this special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology.

Conflicts of interest

Angas J. M. Hopkins died in 2016 and Graeme T. Smith in 1999. Neither of them, nor Denis A. Saunders have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Angas J. M. Hopkins and Graeme T. Smith were authors of the original version of this paper, which was written for a special bulletin of CALMScience on the Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The paper was subject to peer review, revised, and accepted for publication in 1991. The special bulletin was never published. In resurrecting the papers collected for the special bulletin, in order to publish them over 30 years later in the special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology, Denis A. Saunders updated the paper and edited it for publication as both authors were dead; Graeme T. Smith in 1999 and Angas J. M. Hopkins in 2016. Both authors would have met criteria for authorship if alive, so they are included as authors on this paper. Angas J. M. Hopkins and Graeme T. Smith were grateful to the many people who contributed to the diverse studies they collated for their edited volume. These studies were supported by the Western Australian Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, then the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) (when the Wildlife branch of the department was incorporated into CALM); CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research; and a number of individuals. Their support was gratefully acknowledged. They also thanked Jan Rayner, Raelene Rick, and Jill Pryde for word processing and typesetting. Computing support was provided by Mike Choo and Paul Gioia. Cartography was by the Mapping Branch, Department of Conservation and Land Management and the Australian Survey Office, with technical assistance from Greg Beeston, Western Australian Department of Agriculture. Peter Chalmer and Roland Taylor of Environmental Drafting Services drafted most of the figures and a number of the maps. Many of these figures and maps prepared for Hopkins and Smith’s collection of papers were not available for this special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology. Denis A. Saunders is grateful to Katy Macknay and Lizzie Smith for finding the only relatively complete hard copy of Hopkins and Smith’s legacy and for their encouragement to see it through to publication, Nicole Wreford and Lisa Wright for scouring the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attraction’s library for all archival material relating to Hopkins and Smith’s draft special bulletin of CALMScience, the many contributors who willingly agreed to update their papers accepted in the early 1990s, in some cases agreeing to contribute to the original papers because the original contributors were dead, incapacitated, or uncontactable, although they had no dealings with authors at the time, Dr Geoff Pickup who drafted some of the maps and ran the 1991 hard copy through optical recognition software, Alan Danks and Professor Stephen Hopper AC for providing photographs, Emeritus Professor Mike Calver and Professor Stephen Hopper AC for critical comments on an earlier draft of this paper, Emeritus Professor Mike Calver (editor-in-chief Pacific Conservation Biology) for his encouragement and support with the special issue, and the many people who peer reviewed the papers for this special issue.

References

Charles SP, Silberstein R, Teng J, Fu G, Hodgson G, Gabrovsek C, Crute J, Chiew FHS, Smith IN, Kirono DGC, Bathols JM, Li LT, Yang A, Donohue RJ, Marvanek SP, McVicar TR, Van Niel TG, Cai W (2010) Climate analyses for South-West Western Australia. A report to the Australian Government from the CSIRO South-West Western Australia Sustainable Yields Project. (CSIRO, Australia) pp. 83. doi:10.4225/08/584d9590d046b

Chatfield GR, Saunders DA (2024) History and establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24004.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hart R, Freebury G, Barrett S (2024) Phytophthora cinnamomi: extent and impact in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia (1983–2024). Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24028.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hennessy K, Fawcett R, Kirono D, Mpelasoka F, Jones D, Bathols J, Whetton P, Stafford Smith M, Howden M, Michell C, Plummer N (2008) An assessment of the impact of climate change on the nature and frequency of exceptional climatic events. (Commonwealth of Australia: Barton, Australian Capital Territory)

Knapp L, Cummings D, Cummings S, Fielder PL, Hopper SD (2024) A Merningar Bardok family’s Noongar oral history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and surrounds. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24018.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA (2023) The breeding biology of the Western Red-tailed Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus escondidus in the wheatbelt of Western Australia. Australian Zoologist 43(2), 199-219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Saunders DA, Mawson P, Dawson R (2011) The impact of two extreme weather events and other causes of death on Carnaby’s Cockatoo: a promise of things to come for a threatened species? Pacific Conservation Biology 17, 141-148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sinclair EA, Danks A, Wayne AF (1996) Rediscovery of Gilbert’s Potoroo, Potorous tridactylus, in Western Australia. Australian Mammalogy 19(1), 69-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |