Utilisation of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in NSW, 2008–2010

John C. Skinner A B , Peter List A and Clive Wright AA Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW

B Corresponding author. Email: john_skinner@wsahs.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(2) 5-11 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB11048

Published: 28 March 2012

Abstract

Aim: To examine the use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in NSW, its uptake in the private and public dental sectors and to map the geographical pattern of program use. Methods: Data describing the use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan were assembled from a variety of sources including Medicare, the NSW Oral Health Data Collection and the NSW Teen Dental Survey 2010. Results: In 2010, use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan across the entire NSW eligible aged population ranged from 20 to 25.5%, with the average usage across all ages being 20.2%. For the period 2002 to 2010, the average utilisation rate for teenagers accessing public dental care was approximately 6.8%. Conclusion: As a single Dental Benefits Schedule item is used for service provided under the Plan, it is difficult to evaluate the mix of dental treatment items and the comparative value of the service provided unless these services are provided in a public dental service with a data collection that can flag care provided under a Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher.

The Medicare Teen Dental Plan was introduced on 1 July 2008 after being announced as an election commitment by the Commonwealth Labor Government.1 The Medicare Teen Dental Plan provides a $163.05 voucher (indexed annually) that aims to promote life-long good oral health habits. Vouchers are sent to eligible teenagers in January and February each year, and must be redeemed within the calendar year of issue.

At a minimum, each voucher is to provide an oral examination and other necessary diagnostic or preventive dental items that can be provided within the dollar value of the voucher.1 Parents or teenagers may face out-of-pocket costs if private dentists charge above the voucher amount, or if additional treatment is required. To be eligible for a voucher, a teenager must, for at least some part of the calendar year, be aged between 12–17 years, and meet a means test. The means test involves the teenager or his or her family, caregiver, guardian or partner being eligible for one or more of a range of Australian Government benefits or allowances.2 Approximately 1.3 million (65%) of the Australian population aged 12–17 years were eligible for a Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher in 20081 reducing to 1.2 million in 2010.3 A similar proportion of teenagers were eligible in New South Wales (NSW).

The implementation of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan required a legislative framework for the payment of dental benefits to be established.4 After consultation with the State and Territory Dental Directors and Chief Dental Officers, the Medicare Teen Dental Plan implementation was amended so that vouchers could be claimed through public oral health services. This is a notable difference from the Medicare Chronic Disease Dental Scheme, which has not been available through public oral health services.

Each of the former Area Health Services (now Local Health Districts) in NSW has been providing services under the Medicare Teen Dental Plan since the program began, as all children and young people under 18 years of age are eligible for NSW Public Oral Health Services. Arrangements were made for the processing and claiming of the vouchers through a Representative Public Dentist’s Medicare provider number5 in each of the former Area Health Services. The benefits claimed by the Representative Public Dentist are paid to an Area Health Service account.

We examined the use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in NSW and compared this with its use in other Australian jurisdictions. We also examined uptake in the private and public dental sectors in NSW and mapped the geographical pattern of program use.

Methods

All dental services data for children and adults accessing public dental care in NSW are captured in the Information System for Oral Health. Data were extracted monthly from each former Area Health Service’s Information System for Oral Health database and reported to the NSW Oral Health Data Collection. Data on the use of public dental services were extracted for the 9 years from 2002 to 2010 for all young people aged 12 to 17 years at the time of service delivery. Data for each teenager presenting with a Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher or referral indicator were also extracted from the demographics table in the Information System for Oral Health. Where possible, these data were matched to a unique treatment visit that occurred in the same year as the use of the voucher.

For the last 3 years of the period 2002 to 2010, the Medicare Teen Dental Plan was in place and each of the former Area Health Services accepted Medicare Teen Dental Plan vouchers. A NSW Health Policy Directive mandates the use of a Medicare Teen Dental Plan indicator for each year that the teenager uses their voucher in the public dental system.6 The use of this indicator has only been fully implemented recently in some parts of the state which means that the available data underestimate the true number of teens attending dental clinics with vouchers.

In 2010 a randomised, statewide Teen Dental Survey (unpublished) examined the oral health of a random representative sample of Year 9 students aged 14–15 years in NSW. This survey included a questionnaire completed by the teenager and his or her parents about the teenager’s oral health-related behaviours and use of dental services, including the Medicare Teen Dental Plan. The data from these questionnaire responses were analysed.

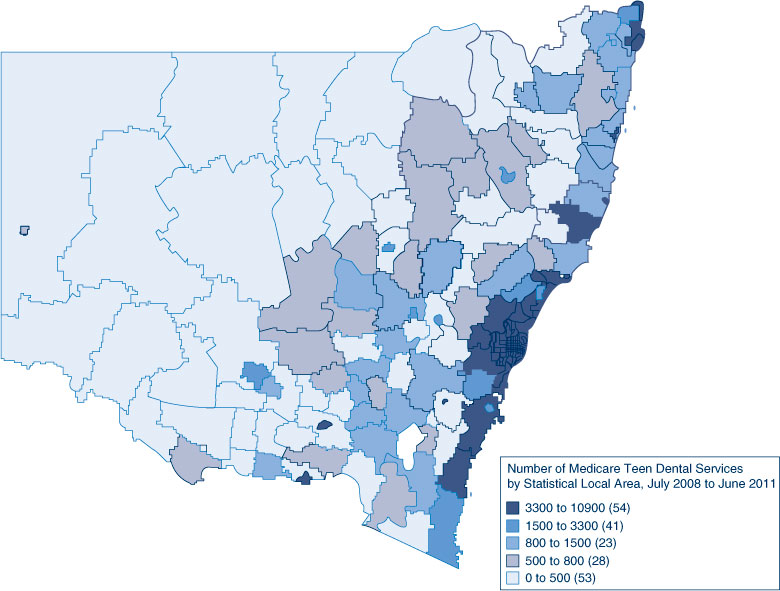

Data on the number of services provided and the value of vouchers claimed under the Medicare Teen Dental Plan by all Statistical Local Areas in NSW were obtained for the period 2008 to 2011 from the Department of Human Services National Office by formal request. In addition voucher claims data for all Australian jurisdictions was obtained from the Medicare Statistics website for the period 2008 to 2011. All datasets were analysed using SAS 9.2.7 The Medicare data were also mapped for each NSW Statistical Local Area using the Geographical Information System software, MapInfo version 11.8

Results

At the end of June 2011, $189.9 million in benefits had been claimed in Australia under the Medicare Teen Dental Plan since July 2008 with $68.6 million of benefits claimed for NSW teenagers (Table 1). Since the scheme commenced in July 2008, 1 270 409 services have been claimed in Australia with 453 138 services in NSW (Table 2). In the first financial year in NSW (2008–9), 168 580 services were claimed in NSW declining to 136 572 services claimed in the financial year 2010–11.

|

In the 2010 calendar year, use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan was slightly higher in younger age groups, and rates of use declined in older teenagers (Table 3). Use of the scheme in the NSW population aged 12-17 years ranged from 20% among 17 year olds to 25.5% among 13 year olds. As the age requirements of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan includes teenagers who are aged between 12–17 years for only part of the calendar year, there was also some use of vouchers by teenagers who were younger than the scheme’s target group (10.6% of 11 year olds used a voucher) and those older (10.5% of 18 year olds). The average use across all ages 11–18 years was 20.2%.

|

The distribution of Medicare Teen Dental Plan services claimed for NSW for the period July 2008 to June 2011 (Figure 1), and the distribution of Medicare Teen Dental Plan services for the Sydney Metropolitan area for the same time period (Figure 2) show that, while services are largely concentrated in the highly populated coastal areas of NSW, there has been uptake of the Plan in regional and rural areas west of the Great Dividing Range.

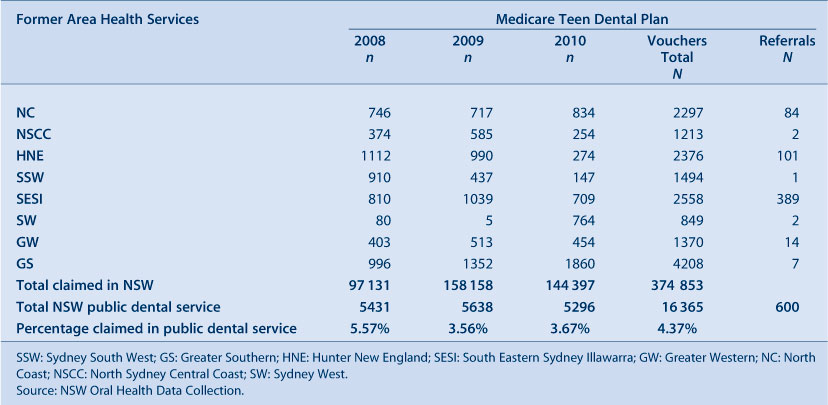

Table 4 describes the use of public dental system in each of the former Area Health Services by all young people aged 12–17 years at the time of service for the period 2002 to 2010. This represents an average utilisation rate of approximately 6.8% of public dental services for the period 2002 to 2010.

|

Despite the limitations of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan indicator, there appears to be a slight increase in the number of teenagers accessing the public dental system between 2008 and 2010 compared to the overall period of 2002 to 2010 (Table 4).

Of the 16 365 teenagers with a Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher indicator between 2008 and 2010 (Table 5), 12 789 (78.1%) were able to be matched with a unique visit identifier in the same year as the voucher indicator (Table 6).

|

|

In 2010, 901 (80%) of parent respondents in the NSW Teen Dental Survey reported receiving a Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher. Of these, 528 teenagers had used the voucher, with 477 (90.3%) having used it at a private dentist and 9.7% reported using it in the public sector. However, a comparison of data from the Information System for Oral Health with Medicare data on total vouchers claimed in NSW indicates that only 3.7% were through the public oral health service in 2010 and 3.6% in 2009 (Table 5).

Referral pathways between private and public sectors have also been developed to ensure continuity of care for those patients who have redeemed their voucher privately, but require further care in the public sector. Between 2008 and 2011 in NSW, 600 teenagers were recorded as presenting to the public dental service for follow-up dental care after claiming their vouchers at a private dental practitioner (Table 5). Unlike vouchers, referrals are not differentiated by a new indicator each year and so it is not possible to examine these data by year from the Information System for Oral Health.

Discussion

When compared nationally, the use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in NSW is largely proportional to population. Use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan as a percentage of the total NSW teenage population (11–18-year olds) shows differences between age groups with use declining in older teenagers. The decline in usage across the ages may be a result of declining interest in the program as older teenagers may already have had two previous preventive visits under the Plan or it may represent changing circumstances, such as increasing independence from parents or caregivers who previously encouraged them to use their Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher.

There has been a notable decline in the number of vouchers claimed since 2008. This may be due to changes in the number of teenagers eligible for the Plan, or represent a waning awareness of the program following the initial implementation phase. Other factors that might contribute to the decline are that some teenagers used a voucher and were assessed as having no disease, or required treatment beyond the scope of the items offered under the voucher or beyond their ability to pay for these additional services.

Uptake of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in the NSW public dental service has varied, both across the former Area Health Services, and over the years of operation. This is likely due to a range of factors including existing high demand for services and concerns during the first 12 months of implementation about taxation liability for the Representative Public Dentist. This taxation liability issue was resolved in 2010 with a ruling from the Australian Taxation Office.4

Recent declines in the number of vouchers claimed in some areas may represent a failure to maintain accurate data entry in the Information System for Oral Health through use of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher indicators. It was not possible to match all Medicare Teen Dental Plan voucher indicators with visit data from the Information System for Oral Health in a way that could be reliably used to investigate treatment provided to teenagers in NSW public dental services.

There was a notable difference in the reported use of Medicare Teen Dental Plan vouchers in the public sector from the 2010 NSW Teen Dental Survey (9.7%) and the data from Medicare and the Information System for Oral Health (3.7%). While this difference may be due to sampling factors, an alternative explanation is that the NSW Teen Dental Survey only collected data regarding those people who were eligible by way of the Family Tax Benefit A, whereas the eligibility for the Plan includes a wider range of benefits. If this was the primary cause of the differences, it would suggest that those teenagers who were eligible via the Family Tax Benefit A were more likely to use their vouchers in the public dental service than those teenagers who were eligible under other benefits and allowances.

There are several observations made by the report of the review of the Dental Benefits Act 2008 related to changes to the program that would assist with evaluation. A key issue noted in the report was that data should be provided for each voucher claimed on which of the dental items included under the scheme had been provided rather than the single Dental Benefits Schedule (DBS) item 88000.1 The report noted that this could be achieved by adding an 88 prefix to the existing Australian Dental Association (ADA) treatment item code set in a similar way to the coding of treatment provided under the Medicare Chronic Disease Dental Scheme. This additional coding would allow for quantification of anecdotal evidence of substantial variation in value of services provided under a voucher.1

The review also noted that public feedback on the Medicare Teen Dental Plan included concerns about access to follow-up treatment of oral health issues identified by the preventive dental check, and the potential difficulties experienced by eligible teenagers moving between the private and public dental sectors for follow-up treatment.1 When vouchers are redeemed in the public sector, treatment identified in the oral examination can be provided to the teenager free of charge and with continuity of care.

Conclusion

The Medicare Teen Dental Plan provides an important opportunity to provide preventive dental care to teenagers, particular to those who may not otherwise seek it. It remains unclear, however, whether the Plan will meet the long-term objective to encourage teenagers to have a regular preventive dental check as they become independent adults, and therefore ongoing monitoring of these teenagers beyond the target age groups of the Plan is required. The decline in use of vouchers as teenagers get older may be of particular concern in this respect, and would suggest that further effort is required to sustain usage as teenagers get older and become more independent.

This examination of the utilisation of the Plan in NSW raised concerns with respect to the lack of uptake, the equity of uptake of vouchers and the number of providers available or willing to accept vouchers in certain rural and regional areas of NSW. A lack of support for the provision of follow-up care in the private sector is also of concern, and could contribute to additional pressures being placed on the NSW public oral health service which are not offset by revenue from the Plan.

With only a single Dental Benefits Schedule item used for services provided under the Plan, it is difficult to evaluate the mix of dental treatment provided and the comparative value of the services delivered. Better capture of the full range of dental care provided under each voucher is needed for more effective monitoring and evaluation of the Plan and its goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Human Services National Office for supplying the Medicare service and claims data.

References

[1] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Report on the Review of the Dental Benefits Act 2008. Publications Approval Number 6334. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/BF6EEBDAEAB570BBCA2576E7000854DF/$File/DoHA%20Dental%20Benefits_LR.pdf (Cited 21 November 2011).[2] Department of Health and Ageing. Medicare Teen Dental Plan. Questions and answers. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/dental-teen-questions (Cited 17 November 2011).

[3] Department of Health and Ageing. Annual Report 2010/11. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/annual-report2010-11 (Cited 26 January 2012).

[4] Biggs A, Biddington M. Dental Benefits Bill 2008. Bills Digest, 13 June 2008, no. 135, 2007–08. Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services. Available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/bd/2007-08/08bd135.pdf (Cited 21 November 2011).

[5] Health NSW. Information Bulletin 2009_042: Representative Public Dentist – Commonwealth Medicare Teen Dental Program. August 2009. Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/ib/2009/pdf/IB2009_042.pdf (Cited 21 November 2011).

[6] Health NSW. Policy Directive 2008_056: Priority Oral Health Program and List Management Protocols. September 2008. Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2008/pdf/PD2008_056.pdf (Cited 21 November 2011).

[7] SAS Institute. 2010. The SAS System for Windows version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

[8] Pitney Bowes Software Inc. MapInfo 11. One Global View, Troy, New York 12180-8399.