Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, May and June 2011

Communicable Diseases BranchNSW Department of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 22(8) 162-167 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB11030

Published: 20 September 2011

| For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Public Health and then Infectious Diseases. The communicable diseases site is available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp. |

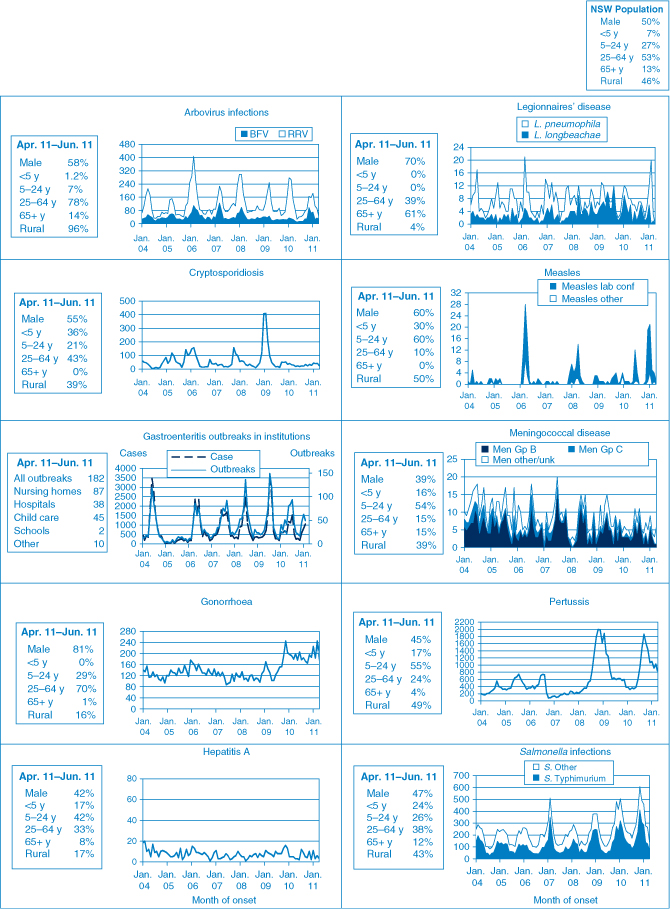

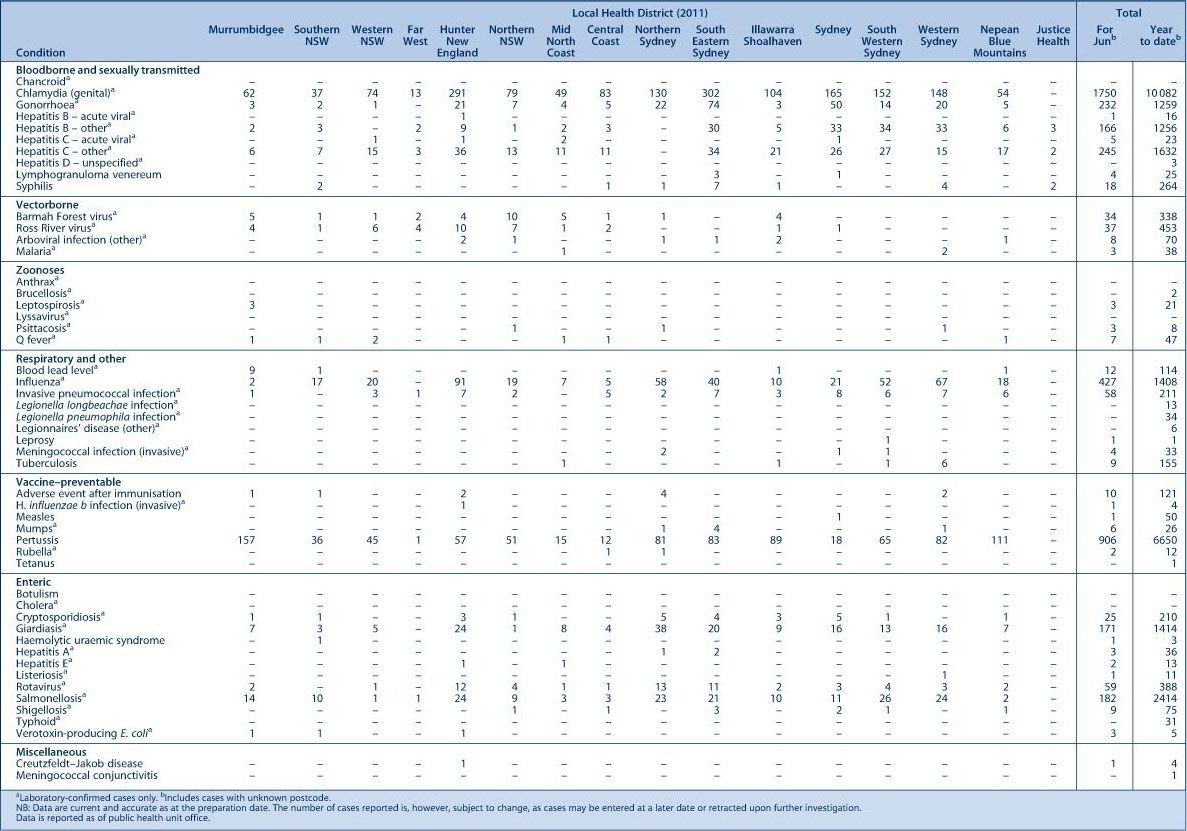

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show notifications of communicable dise ases received in May and June 2011 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

Enteric infections

Outbreaks of foodborne disease

Twelve outbreaks of suspected foodborne disease were investigated in May and June 2011. These outbreaks were identified through: the surveillance of laboratory notifications, complaints to the NSW Food Authority (NSWFA) or complaints to the local public health unit. In two of these outbreaks the causative organism was identified: one as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and one as norovirus.

The S. Typhimurium outbreak was identified through a complaint to the NSWFA. Interviews with the affected people found illness to be associated with the consumption of prawn dumplings from a café. The four affected people who consulted a general practitioner submitted stool specimens, three of which were positive for S. Typhimurium. The NSWFA inspected the business and took food samples and environmental swabs, however no pathogen was identified from these specimens. As the business was also serving aioli prepared with raw egg, and given the risk of using raw egg in uncooked foods, they were advised to use an alternative ingredient.1

Salmonella infections can occur after eating undercooked food made from eggs, meat or poultry.2 Thorough cooking of food kills Salmonella bacteria and it is therefore advisable to avoid consumption of raw or undercooked meat, poultry, or eggs, especially for young children, elderly people and people with an immunosuppressive condition.

The norovirus outbreak was also identified through a complaint to the NSWFA after several groups of people developed vomiting and diarrhoea approximately 24 hours after eating food at a bowling club over a weekend. The public health unit interviewed 113 people from the 240 who visited the club during the weekend. Of those interviewed, 86 (76%) had developed symptoms of gastroenteritis. Five people were hospitalised and two stool specimens from those hospitalised returned a positive result for norovirus. The club’s chef had been working while unwell with gastroenteritis and is likely to have contaminated food whilst preparing it. The NSWFA inspected the kitchen and took numerous environmental swabs, some of which were positive for norovirus. No foods were left over to sample. The NSWFA ordered a thorough disinfection of the venue and issued a prohibition order until staff passed a skills and knowledge test.

Norovirus infection is a viral infection resulting in vomiting and diarrhoea. The virus is easily spread from person to person. Thorough washing of hands with soap and running water helps to prevent its spread. Anyone with vomiting or diarrhoea should stay at home and not attend work, school or child care or visit a residential care facility until their vomiting and diarrhoea have stopped for 48 hours. During this time they should also not prepare food for others, or care for patients, children or the elderly.

Outbreaks of gastroenteritis in institutional settings

During May and June, 133 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in institutions were reported, affecting 1923 people. Sixty-three outbreaks occurred in aged care facilities, 35 in child care centres, 28 in hospitals, two in schools, and five in other settings such as rehabilitation facilities. These outbreaks appear to have been caused by person-to-person spread of a viral illness. In 81 outbreaks (61%) one or more stool specimens were collected from cases. Norovirus was detected in 50 of these outbreaks (62%); in three outbreaks Clostridium difficile was also detected alongside norovirus. Rotavirus was detected in six outbreaks (and norovirus was also identified in four of these). Stool specimens for laboratory testing were not available for the remaining 52 outbreaks (39%).

The incidence of viral gastroenteritis increases in winter months. Public health units encourage institutions to submit stool specimens from cases for testing during outbreaks to help determine the cause of the outbreaks.

Respiratory and other infections

Influenza

Influenza activity was low during May, but increased to moderate levels during June (as measured by the number of people who presented to 56 of the state’s largest emergency departments with influenza-like-illness and the number of patients who tested positive for influenza at diagnostic laboratories). The rate of laboratory-confirmed influenza activity was above the expected level for this time of year. There were 136 emergency department presentations of patients with influenza-like illness in May (0.9 per 1000 emergency department presentations), and 313 presentations of patients with influenza-like illness in June (1.7 per 1000 emergency department presentations).

There were 141 notifications of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases in May and 427 in June. For a more detailed report on respiratory activity in NSW see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/Infectious/influenza_reports.asp

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Meningococcal disease

Ten cases of meningococcal disease were notified in NSW in May and June 2011 (five in May and five in June). The age of these people ranged between 0 and 65 years and included two children aged less than 5 years. No deaths were notified in this period, compared to three deaths for the same period in 2010. Four cases were caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B and one by N. meningitidis serogroup Y. For the remaining five cases the serogroup was either unable to be determined or the serogroup results are pending.

A free vaccine for serogroup C meningococcal disease is available for infants at 12 months of age.3 Consequently, serogroup C meningococcal disease is now mainly seen in adults and in unimmunised children. In NSW this year, 75% of cases of meningococcal disease (where the serogroup was known) have been caused by N. meningitidis serogroup B, for which there is no vaccine. No cases of serogroup C disease have been reported to date this year.

Sexually transmissible infections

Gonorrhoea

Notifications of gonorrhoea increased during May and decreased during June 2011. The decrease in June may be due to a reporting delay. Notifications have fluctuated each month in the first half of 2011.

In total in this period 411 cases of gonorrhoea were notified to NSW Health (247 in May and 164 in June), compared to 383 (180 in May and 203 in June) in 2010. The majority of notifications continue to occur in men. However, 78 women were notified with gonorrhoea in May and June, compared to 60 cases notified for the same period in 2010.

Gonorrhoea is a bacterial infection spread through unprotected vaginal, oral or anal sex. Infection in men can present as discharge from the penis, irritation or pain on urinating. Infections of the cervix, anus and throat usually cause no symptoms.2

Syphilis

Notifications of infectious syphilis cases continued to decrease during May and June 2011. In total, 38 cases of infectious syphilis were notified in this period (30 in May and eight in June). This is substantially less than the 150 cases notified in the corresponding period in 2010. A reporting delay may account for some of this difference. The majority of cases continue to occur in men aged between 20 and 50 years.

Syphilis is a highly infectious sexually transmitted disease that is spread through vaginal, anal or oral sex through skin-to-skin contact. Syphilis is highly contagious during the primary and secondary stages when the sore or rash is present.2 Those most at risk include men who have sex with men and people with HIV/AIDS. Some people living in remote Aboriginal communities are also at increased risk.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

An outbreak of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) was identified in NSW in 2010 with a peak in cases notified between May and August (32 cases). Since then the number of cases notified has dropped, with only six cases notified in May and June 2011 (five in May and one in June).

LGV is a sexually transmitted infection. It is caused by a rare, invasive form of Chlamydia trachomatis which generally causes more severe symptoms than chlamydia. LGV is spread through unprotected vaginal, anal or oral sexual contact.2

References

[1] NSW Food Authority. Safe handling of raw egg products. Available from: http://www.foodauthority.nsw.gov.au/_Documents/industry_pdf/safe_handling_raw_egg_products.pdf (Cited July 2011.)[2] Heymann DL, ed. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 19th ed. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2008.

[3] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2008.