NSW Annual Adverse Events Following Immunisation Report, 2009

Deepika Mahajan A D , Sue Campbell-Lloyd B , Ilnaz Roomiani C and Robert I. Menzies AA National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance,The Children’s Hospital at Westmead

B AIDS and Infectious Diseases Branch,NSW Department of Health

C Office of Medicine Safety Monitoring,Therapeutic Goods Administration

D Corresponding author. Email: DeepikM2@chw.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 21(10) 224-233 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB10048

Published: 18 November 2010

Abstract

Aim: This is the first annual report for NSW of adverse events following immunisation. It summarises Australian passive surveillance data for adverse events following immunisation for NSW for 2009. Methods: Analysis of de-identified information on all adverse events following immunisation reported to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Results: 450 adverse events following immunisation were reported for vaccines administered in 2009; this is 32% higher than 2008 and the highest since 2003. The increase was almost entirely attributed to the commencement of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccine in September 2009. Only 6% of the reported adverse events were serious in nature and the most commonly reported reactions were allergic reaction, injection site reaction, fever and headache. Conclusion: Reports of adverse events following immunisation in 2009 were dominated by the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccine. A large proportion of these adverse events were reported directly to the Therapeutic Goods Administration by members of the public. Reports were predominantly mild transient events, similar to those expected from the seasonal flu vaccine.

Adverse events following immunisation are defined as unwanted or unexpected events following the administration of a vaccine(s). They may be caused by a vaccine(s) or may be coincidental. Adverse events may also include conditions that occur following the incorrect handling and/or administration of a vaccine(s). The post-licensure surveillance of adverse events following immunisation is important to detect rare, late onset and unexpected events which are difficult to detect in pre-licensure vaccine trials.

This is the first annual report for adverse events following immunisation in New South Wales (NSW). It summarises passive surveillance data reported from NSW in 2009 and describes reporting trends over the 10-year period 2000–2009. To assist readers, at the end of this report is a glossary of the abbreviations of the vaccines referred to in this issue (Box 1).

|

Trends in reported adverse events following immunisation are heavily influenced by changes to vaccines provided through the National Immunisation Program. Changes in previous years have been reported elsewhere.1–12 The most significant change during 2009 was the introduction of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccine which was rolled out nationally on 30 September for those aged 10 years and over. In December 2009 the pandemic vaccine was made available to children aged from 6 months to 10 years.

Methods

Adverse events following immunisation are notifiable to public health units by medical practitioners and hospital CEOs under the NSW Public Health Act 1991. They are investigated by public health units and NSW Health and forwarded to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. The Therapeutic Goods Administration also receives reports directly from vaccine manufacturers, members of the public and other sources.13,14 All reports are assessed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration using internationally-consistent criteria15 and entered into the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database.

Adverse events following immunisation data

De-identified information on adverse events following immunisation reports from the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database was released to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance for analysis and reporting. Adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) records contained in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if: a vaccine was recorded as ‘suspected’ of involvement in the reported adverse event; the vaccination occurred between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2009; and the residential address of the individual was recorded as NSW. If the vaccination date was not recorded the date of onset of symptoms or signs was taken as the date of vaccination.

The term ‘AEFI record’ is used throughout this report because a single adverse event notification to the Medicine Safety Monitoring Unit can generate more than one record in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database. This may occur if there is a time sequence of separate adverse reactions in a single patient.

AEFI records are classified as ‘suspected’ by the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee, an expert committee of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. An AEFI record is excluded from the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee database if: there is no reasonable temporal association between the use of a drug and the clinical event; the record does not contain enough information for an adequate assessment or the information is contradictory; or if a clinical event is explained as likely to have arisen from other causes.

Study definitions of adverse events following immunisation outcomes and reactions

AEFIs were defined as ‘serious’ or ‘non-serious’ based on information recorded in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database and using criteria similar to those used elsewhere.15,16 In this report, an AEFI is defined as ‘serious’ if the record indicated that the person had recovered with sequelae, been admitted to a hospital, experienced a life-threatening event, or died.

The causality ratings of ‘certain’, ‘probable’ and ‘possible’ are assigned to individual AEFI records by the Therapeutic Goods Administration. They describe the likelihood that a vaccine or vaccines was or were associated with a reported reaction in an individual. Factors that are considered in assigning causality ratings include: timing (minutes, hours, etc. following vaccination); spatial correlation (for injection site reactions) of symptoms and signs in relation to vaccination; and whether one or more vaccines were administered. These factors are outlined in more detail elsewhere.17 Because children generally receive several vaccines at the same time, all administered vaccines are usually listed as ‘suspected’ of involvement in a systemic adverse event as it is often not possible to attribute the event to a single vaccine.

Typically, each AEFI record listed several symptoms, signs and diagnoses that had been re-coded by Therapeutic Goods Administration staff from the description provided by the reporter into standardised terms using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®).18 AEFI reports of suspected anaphylaxis and hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes were classified using the Brighton Collaboration case definitions.19,20

Data analysis

All data analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Average annual population-based reporting rates were calculated using population estimates obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.21

AEFI reporting rates per 100 000 administered doses were estimated where information on dose numbers was available from: the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register for vaccines for children aged less than 7 years; NSW Health data on vaccines administered in schools for 12–17 year-olds; and the 2009 NSW Health Survey for influenza and 23vPPV vaccines for adults aged 65 years and over.22 For the 23vPPV vaccine, the dose numbers were divided by five to get the denominator dose numbers for a single year.

Notes on interpretation

The data reported here are provisional only, particularly for the fourth quarter of 2009, because of reporting delays and the late onset of some AEFIs. The information collated in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database is intended primarily to detect signals of adverse events and to inform hypothesis generation. While AEFI reporting rates can be estimated using appropriate denominators, they cannot be interpreted as incidence rates due to underreporting and biased reporting of suspected events, and the variable quality and completeness of information provided in individual notification reports.1–12,23

It is important to note that this annual report is based on vaccine and reaction term information collated in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database and not on comprehensive clinical notes. Individual records in the database list symptoms, signs and diagnoses that were used to define a set of reaction categories based on the case definitions provided in the 9th edition of The Australian Immunisation Handbook.14 These reaction categories are similar, but not identical, to the AEFI case definitions.

The reported symptoms, signs and diagnoses in each AEFI record in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database are temporally associated with vaccination but are not necessarily causally associated with one or more vaccines.

Results

There was a total of 450 AEFI records for NSW in the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions System database with a date of vaccination (or onset of an adverse event if vaccination date was not reported) in 2009. This was a 32% increase on the 340 records in 2008. Sixty-nine percent (n = 312) of the AEFI records during 2009 were reported in the fourth quarter of the year, a substantial increase (93%) from the corresponding period in 2008 (7%, n = 22). Fourteen percent (n = 62) were for children aged less than 7 years and 84% (n = 379) were for people aged 7 years and over. Thirty-three percent (n = 149) were reported by members of the public, 25% (n = 114) by general practitioners, 21% (n = 94) by health care providers via NSW Health, 13% (n = 60) by nurses, 4% (n = 19) by hospitals, 2% (n = 9) by pharmacists and 1% (n = 5) by others. In contrast, during 2008 only 2% (n = 7) of AEFI records were reported by members of the public, 71% (n = 241) were reported by health care providers via NSW Health and the rest (n = 92) were reported by general practitioners (17%), pharmacists (4%), hospitals (3%), nurses and specialists (2% each).

Reporting trends

The AEFI reporting rate for 2009 was 6.2 per 100 000 population, compared with 4.8 per 100 000 population in 2008 (Figure 1). This is the second highest reporting rate for the period 2000–2009, after the peak in 2003 that coincided with the national program for meningococcal C conjugate vaccine and high rates of reporting from the 18-month dose of DTPa (Figure 2). Figure 1 shows that the vast majority of reported events are of a non-serious nature. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate marked variations of reporting levels in association with changes to the National Immunisation Program, such as the commencement of new vaccination programs in 2003, 2005 and 2007, and the removal of the 18-month DTPa dose in 2003.

|

The usual seasonal pattern of AEFI reporting from older Australians receiving 23vPPV and influenza vaccine during the autumn months (March–June) is evident in Figure 3.

Age distribution

In 2009, the highest population-based AEFI reporting rate occurred in infants aged less than 1 year, the age group that received the highest number of vaccines (Figure 4). Compared with 2008, AEFI reporting rates increased among the less than 1 year age group (a 24% increase from 25.6 to 31.8 per 100 000 population) and the 1 to less than 2 year age group (11.5 to 14.9 per 100 000 population) but decreased among the 2 to less than 7 year age group (7.2 to 4.1 per 100 000 population). The increase in AEFI reporting rates among the less than 1 and 1 to less than 2 year age groups is mainly associated with the introduction of the pH1N1 vaccine while the decrease among the 2 to less than 7 year age group is mainly attributed to reduction in AEFI reports following DTPa-IPV and MMR vaccination. Rates also declined for older children and adolescents (13.4 to 4.1 per 100 000 population), mainly attributable to the cessation of the HPV catch-up program. However, there was a three-fold increase in AEFI reporting rates among adults (2.1 to 6.3 per 100 000 population), associated with pH1N1 vaccine introduction.

|

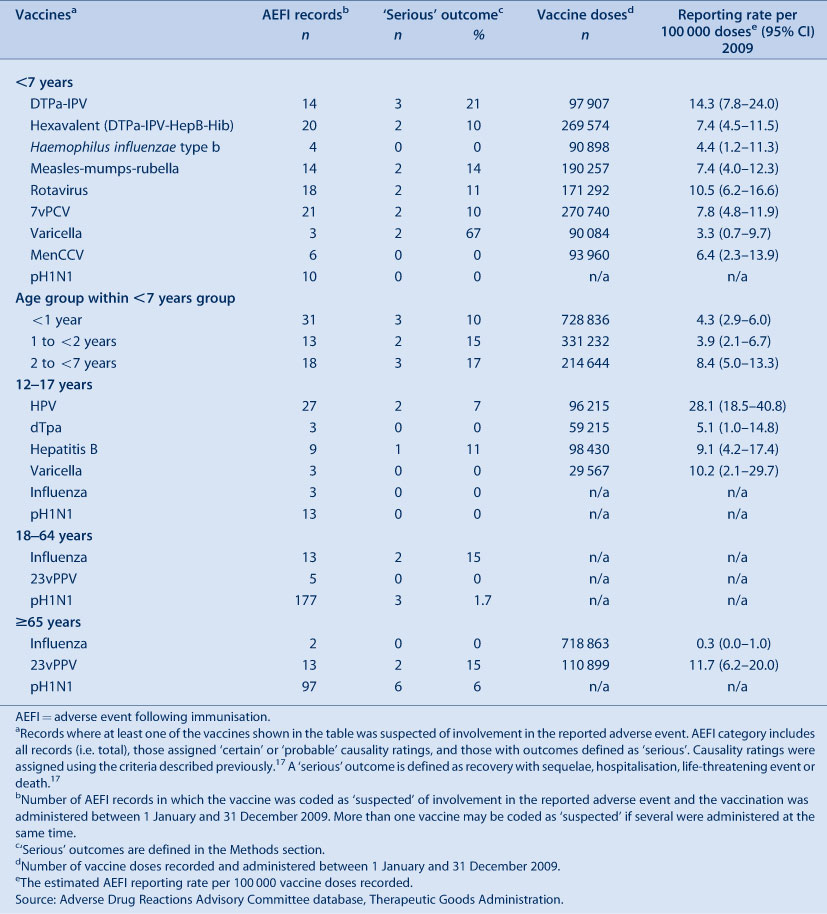

Vaccines

The most frequently reported individual vaccine was pH1N1 with 305 records (68%) (Figure 3). Vaccines containing diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis antigens were reported in 59 (13%) records, with dTpa (23 records, 5%) and hexavalent DTPa-IPV-HepB-Hib (20 records, 4.4%) being the most frequently reported vaccines among DTPa-containing vaccines. The other frequently reported vaccines were: HPV (34 records, 8%); 7vPCV (21 records, 5%); and 23vPPV, rotavirus and seasonal influenza (18 records each, 4%) (Table 1). Of vaccines with reliable data on doses administered, those with the highest AEFI rates per 100 000 doses were HPV (28.1), DTP-IPV (14.3) and rotavirus (10.5).

|

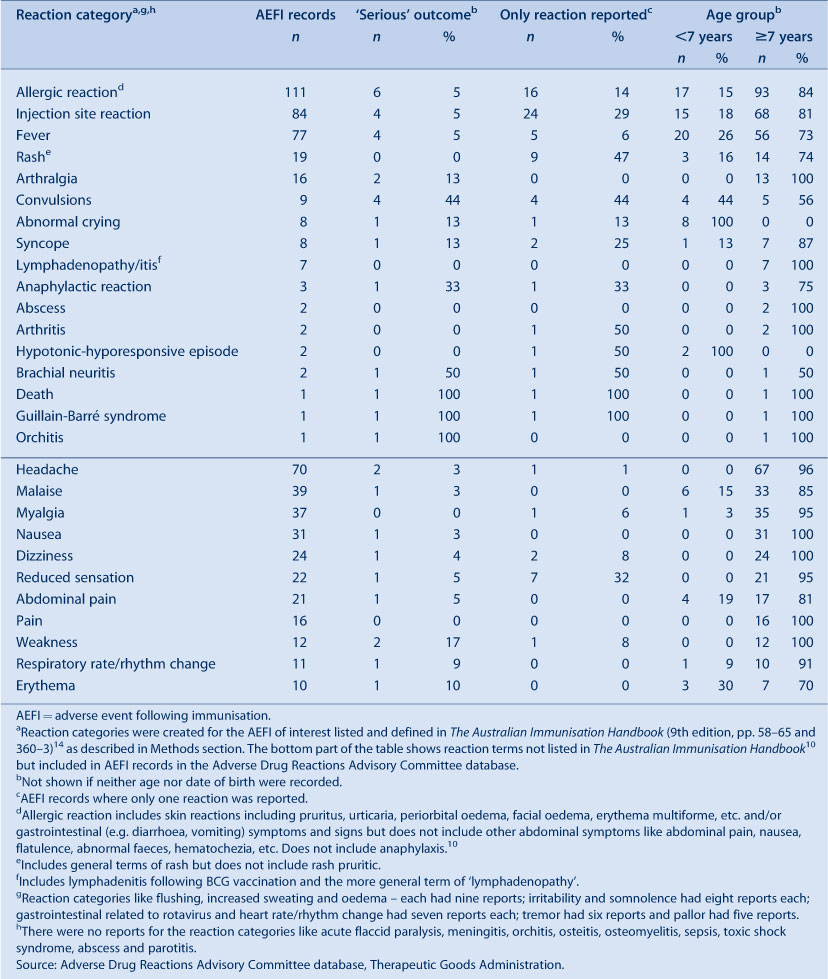

Reactions

The distribution and frequency of reactions listed in AEFI records for 2009 are shown in Table 2. The most frequently reported adverse events were: allergic reaction (25%); injection site reaction (19%); fever (17%); headache (16%); malaise (9%); myalgia (8%); and nausea (7%) (Table 2).

|

AEFIs following pH1N1 vaccine

For pH1N1 vaccine events, 94% (n = 287) were for people aged 7 years and over. Forty-seven percent (n = 146) of the recorded AEFIs were self-reported. There was one report of Guillain-Barrè syndrome in an elderly person and one death. The most frequently reported adverse events were: allergic reaction (n = 79, 26%); headache (n = 60, 20%); fever (n = 53, 17%); and injection site reaction (n = 40, 13%) (Figure 5). There were 10 reports coded as serious and no cases of anaphylaxis.

|

AEFIs following other vaccines

The most frequently reported adverse events following receipt of all vaccines other than pH1N1 (alone or in combination with other vaccines) were: injection site reaction (n = 44, 30%); allergic reaction (n = 32, 22%); fever (n = 24, 17%); headache (n = 10, 7%); convulsions (n = 7, 5%); anaphylaxis (n = 3, 2%); and hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes (n = 2, 1%).

Severity of outcomes

Six percent of events were defined as ‘serious’ (i.e. recovery with sequelae, requiring hospitalisation, experiencing a life-threatening event or death), lower than observed in previous years. Fewer ‘serious’ AEFIs were assigned ‘certain’ or ‘probable’ causality ratings compared with ‘non-serious’ AEFIs (7% versus 14%) (Table 3). Numbers of reported events and events with outcomes defined as ‘serious’ are shown in Table 1.

|

Seventeen percent of records were recorded as not fully recovered at the time of reporting; 68% of these were following receipt of pH1N1 vaccine. Information on severity could not be determined for 47% (n = 211) of records; 83% of these were following receipt of pH1N1 vaccine and 50% of these reports came from members of public with little specific information provided. None were reported through NSW Health. Of those without information describing severity, the most commonly reported adverse reactions were: allergic reactions (22%); fever (18%); headache (17%); injection site reaction (16%); malaise and myalgia (11% each); nausea (9%); abdominal pain and dizziness (6% each); and weakness (4%).

The more severe reported AEFIs were: convulsion (n = 9), including two febrile convulsions; hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode (n = 2); Guillain-Barré syndrome (n = 1); and death (n = 1). Of the nine cases of convulsion, four were children aged less than 7 years. The most commonly suspected vaccines were: HPV (n = 3); pH1N1 (n = 2); hexavalent and pneumococcal (n = 2); dTpa (n = 1); and varicella (n = 1). Both reports of hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes were from children aged less than 7 years following administration of DTPa/IPV and HepB vaccines.

There was a report of one death – a middle-aged man who had been vaccinated 1 day prior – which was recorded as temporally associated with receipt of pH1N1 vaccine. The man was well when seen approximately 8 hours post-vaccination and no other reactions were observed or reported. He had suffered an inferior myocardial infarct 3 months before receipt of the vaccine and was diagnosed with double vessel coronary disease. It is regarded as unlikely that the vaccine had any role in this patient's death.

Discussion

The increase of both the AEFI records and population-based reporting rates in 2009 is likely due to the introduction of the pH1N1 vaccine in September 2009. Immunisation providers are more likely to report milder, less serious AEFIs for vaccines they are not familiar with. Historical data show that initial high levels of AEFI reporting occur each time a new vaccine is introduced (MenCCV in 2003 and HPV in 2007), followed by a reduction and stabilisation of reporting over time (Figure 3). This tendency to report newer vaccines increases the sensitivity of the system to detect signals of serious, rare or previously unknown events, but also complicates the interpretation of trends. However, the large number of reports from members of the public in comparison to previous years indicates a high level of public interest in the pH1N1 vaccine. The enhanced reporting of AEFIs from members of the public is also likely because the H1N1 influenza vaccination program used strategies to encourage consumers and health professionals to report adverse events to allow the Therapeutic Goods Administration to closely monitor the safety of the vaccine.24

The safety of the pH1N1 vaccine has been examined closely both nationally and internationally. The World Health Organization reports that approximately 30 different pH1N1 vaccines have been developed using a range of methods.25 All progressed successfully through vaccine trials to licensure, showing satisfactory safety profiles. However, these clinical trials were not large enough to detect rare adverse vaccine reactions which occur with a frequency of less than one in one thousand. In general the safety profile, including that for the Australian vaccine, has been similar to those of seasonal influenza vaccines, with predominantly mild transient events and a small number of serious reactions reported.26 The NSW data presented here include very few reports from children, as the pH1N1 vaccine was only licensed for children in December 2009. However, the data presented here on adults are consistent with previous data. While Guillain-Barré syndrome has been associated with a previous swine influenza vaccine in 1976,27 international assessment of the current vaccines have found either no association,25 or a slightly higher rate in vaccinees (one per million vaccine doses) consistent with estimates for seasonal influenza vaccine.28 Initial national analysis by the Therapeutic Goods Administration has shown no indication of an increased rate of Guillain-Barré syndrome, or anaphylaxis (another serious reaction of concern) associated with the pH1N1 vaccine in Australia.29

Conclusion

There was a 32% higher rate of AEFIs reported from NSW in 2009 compared with 2008. This increase is attributable to a large number of reports following receipt of the pH1N1 vaccine. A large proportion of these events were reported directly to the Therapeutic Goods Administration by members of the public. However, the reports were of mild transient events, consistent with experience in other countries and similar to the well-established safety profile of seasonal influenza vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance is supported by the Department of Health and Ageing, the NSW Department of Health and The Children’s Hospital at Westmead.

[1] Lawrence G, Boyd I, McIntyre P, Isaacs D. Surveillance of adverse events following immunisation: Australia 2002 to 2003. Commun Dis Intell 2004; 28(3): 324–38.

| PubMed | (Cited 1 February 2009.)

[16] Zhou W, Pool V, Iskander JK, English-Bullard R, Ball R, Wise RP, et al. Surveillance for safety after immunization: Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)–United States, 1991–2001. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003; 52(1): 1–24.

| PubMed | (Cited 26 August 2010.)