Understanding policy influence and the public health agenda

Jenny M. LewisSchool of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne Email: jmlewis@unimelb.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(8) 125-129 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB08063

Published: 7 September 2009

Abstract

This paper analyses how the policy process is shaped by networks of influence. It reports on a study of health policy influence in Victoria, describing the theoretical framework and the methods used. Social network analysis, combined with interviews, was used to map the network’s structure, identify important individuals and examine issues seen to be important and difficult. Which issues an individual is interested in are related to where that person sits within the network. It also demonstrates how influence structures the health policy agenda, and provides insights for public health practitioners who aim to influence policy.

Policy analysis is a broad church, covering numerous theoretical frameworks and empirical approaches. Depending on how policy and politics are defined, policy analysis can be a highly rational endeavour, focused on specific instances of policy, or highly political and concerned with examining how policy is made.

This paper is focused on politics and the policy-making process. Rather than examining a specific example of policy development, it analyses the factors that shape and constrain the policy process. Political scientists, in analysing the policy process, concentrate on institutions, interests and ideas. An institutional approach examines the impact of political institutions such as systems and regimes of government, and a range of factors that generate veto points.1 Steinmo and Watts provide an exemplar of this approach applied to health insurance policy in the United States.2 An interest-based approach examines the influence of powerful interest groups using Marxist or other elitist models of power in society. In health policy, one of the best examples of this is Alford’s book on health care reform.3 Ideas are a less common starting point.4 An ideational approach concentrates on struggles over problem definition, values and the policy paradigms that shape a particular sector.5 There are very few examples of this in health policy, although an exception has been reported.6 This paper analyses both influence and ideas in the making of health policy.

Just as policy analysis employs different theoretical approaches, it also uses an array of methods that borrow from – among others – anthropology, economics, political science and sociology. Documentary analysis, interviews, observations and questionnaire-based surveys are commonly employed. This paper reports on a study that combines different approaches and uses qualitative and quantitative methods side by side.

A study of influence in health policy in Victoria is used as an example. The questions this study aimed to answer, the theoretical framework behind the analysis and the methods used, are described. Combining an initial assessment of who is seen to be influential with more in-depth interviews provides a rich exploration of perceived influence in health policy, and insights into how this helps shape the health policy agenda. The findings are summarised and the benefits of using a combination of methods are highlighted. Finally, some implications for public health are discussed.

Influence in health policy

Kingdon’s landmark study of policy agenda setting began with asking why policy makers pay attention to some things rather than others.7 Why do some issues become the focus of policy action while others languish on the periphery of policy considerations? He analysed the process that leads from the long list of potential things that are swirling around in the ‘policy primeval soup’, to the shortlist of issues that are the focus of serious policy attention.

While Kingdon does not explicitly discuss networks, his description of policy entrepreneurs roaming around, discussing, arguing and amending their policy proposals with others, brings the network idea to mind. The study reported here began with a similar impetus: a concern with policy agenda setting. However, it aimed to examine who was seen to be influential and how these people were connected to each other as the foundation for understanding who was ‘in the soup’ and what ideas they were discussing. This represents a new approach to capturing how the policy agenda is shaped.

This study began in 2001. It aimed to identify who was seen to be influential and what they thought the main health policy issues were. It also aimed to map who recognised whom as influential, and which of them knew each other. The theoretical framework used in this research, along with the methodological approach and the analysis of data, have been described elsewhere.8,9 A brief overview is provided here.

Theoretical framework and concepts

Health policy making, like policy in other sectors, rests on the accumulation and use of power by those involved in the policy process. Examining this is, however, far from straightforward, even when power is used transparently. Several approaches at different levels have been used to understand power and policy making. One useful focus at the macro level is Alford’s work on the dominant, challenging and repressed structural interests that shape health policy.3 However, analysis at this level reveals only a partial story of how health policy is made. If health policy is seen as a complex network of continuing interactions between actors who use structures and argumentation to articulate their ideas about health, then a micro-level approach holds promise for stepping outside the traditional descriptions that accompany examinations of well established and powerful interests.8 Using social network analysis to focus on connections between individuals provides such a framework for analysis.

The networks of interest here consisted of a set of nodes (individuals) linked by direct personal connections (or ties), based on nominations of influence. Conceiving of influence as a network resource that has symbolic utility (whether it is used or not), it is obvious that actors have resources of their own, as well as those they can access through their ties with other actors.10 Mapping social networks of interpersonal ties generates a detailed picture of individual connections, which indicates who has access to resources and who exercises control within a network. The research reported here is perceptual – it is not based on who actually made decisions in a specific instance, or who won a particular debate in parliament. It is focused purely on examining who is regarded as influential. The list of people nominated in this study consisted of senior people in important positions who would be seen to hold power through their organisational positions. This provides some indication that although the network is based on perceived influence, the people nominated are indeed likely to have some influence on policy making.

Network concepts provide a theoretical focal point for thinking about influence in relational terms, and inform research design. Social network analysis was used to design the data collection methods and to shape the data analysis for this study. It has recently started to gain favour in health research. The main concept of interest here is structural equivalence – the idea that people within a network can be seen as equivalent (and interchangeable) in the structure of the network if the patterns of relations between them and their roles are similar. Blockmodelling is a quantitative technique that partitions actors into sub-groups within a network, based on regularities of patterns of relations among actors in the network.11 This means establishing who nominates others in a similar pattern, and who is nominated by others in similar patterns. A second important network concept is centrality, a measure of an individual’s importance: in this case, how highly nominated an individual is by others in the network.12

Methods

Mapping influence first requires the identification of influential actors. Some methods for doing this define influential actors as those holding positions in the top levels of relevant organisations. Other methods rely on reputation, using people to nominate others whom they consider influential. Both of these methods have shortcomings – the first by assigning influence to people in senior positions in certain organisations, regardless of their ability to influence events, and the second by potentially leading to the nomination of those who simply make the most noise. A reputational approach was used in this study since it was regarded as less problematic given the focus on individuals rather than positions and organisations.

A non-medically qualified academic, who had previously held senior positions in several different governments across Australia, was the starting point for nominations. This person was asked to nominate a list of people regarded as influential in health policy in Victoria. The definition of influence used was:

… a demonstrated capacity to do one or more of the following: shape ideas about policy, initiate policy proposals, substantially change or veto others’ proposals, or substantially affect the implementation of policy in relation to health. Influential people are those who make a significant difference at one or more stages of the policy process.9

The process then snowballed from this individual’s list of nominations. Details of how this was done and the criteria for stopping the process are described elsewhere.9 Nominees were not provided with others’ lists, and no set number of nominations was asked for. At the end of this process, 62 people had returned nomination forms, noting whether they had ongoing contact with those they nominated. The majority of ties (82%) were to people the nominator claimed to have ongoing contact with, so this group of nominators appear to have based their judgments of influence on whom they knew personally. However, an actor moving in these circles who is highly nominated as influential is sure to know other influential actors. While the means of generating these nominations could be defined as qualitative (since people were given an open-ended question about who is influential), examining structural equivalence is based on a quantitative analysis of patterns of nominations, as described earlier.

The second part of this research identified the issues these influential people saw as important. Twenty people, spread across the network, were interviewed. They were asked to name:

-

up to five issues they regarded as the most important in current Victorian health policy; and

-

any issues they saw as being particularly difficult or neglected.

The interviews were open-ended, with plenty of time for interviewees to talk through the issues they nominated with some prompting. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the issues grouped thematically based on the interviewees’ explanation of what each issue involved. These transcribed descriptions were also used to assess the way in which the interviewees spoke about particular issues, focusing on the words used and their decisiveness or hesitation in discussing them. While this is an open-ended qualitative approach, the data generated were used both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Analysing influence and issues

Network structure, based on the data gathered from the people who completed nomination forms in this study, was analysed using a blockmodelling procedure. This generated eight blocks, two of which were central to the structure of the network and highly nominated by the other groups as influential. There was a group (block) containing actors in key positions who were both structurally important and highly visible. This included the Victorian Minister for Health, the Minister’s senior political advisor and the Head of the Victorian Department of Human Services (which includes health). This was called the core group, both because all other groups nominated this group as influential, and because it contained people who held important policy positions. The other most important group – public health medicine – is, at first glance, a less obviously influential group of people. These actors were located in universities, research institutes and non-government organisations. All were medically trained and eight of the nine were men.

This analysis provided insights into the structure of this network of influence. Clearly, the core group consisted of those who held positional decision-making power in the policy process. It seems reasonable to assume that whoever occupied these positions would be widely perceived as influential, and also well-placed to exercise influence in policy making. The second group also contained individuals who held senior positions (deans and heads of departments/institutes/organisations), but they were not in designated policy-making positions.

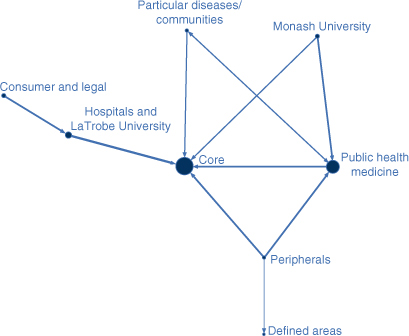

A diagram of this network structure, illustrating the eight groups identified by the blockmodel, is shown in Figure 1. The lines (ties or links) between the groups have different thicknesses based on the percentage of all possible ties between them, with thicker lines indicating (relatively) more frequent nominations of influence. The arrowheads indicate the direction of the nominations. For example, public health medicine nominated the core, but this was not reciprocated, whereas the tie between public health medicine and particular diseases/communities was. The size of the circles (nodes) varies according to the mean number of nominations per person in that block, ranging from a mean of 17.5 for those in the core group, to 2.3 in defined areas. The core block had the most central position in this network, followed by the public health medicine block. The actors in the core block were nominated by people in all the other blocks except the defined areas and consumer and legal blocks.

|

Two or three people from each block were interviewed in order to cover the eight blocks identified. The interview material generated a list of the most frequently mentioned policy issues. Table 1 lists the top six issues nominated by the interviewees, and indicates whether they were mentioned as important or difficult. Two distinct types of issues were identified. The first were those seen to be most important: demand in public hospitals, workforce recruitment and retention, split responsibilities between the Commonwealth and the states and territories and quality of care. The second were those seen to be difficult: health inequalities topped this list. The lack of emphasis on prevention was fairly evenly nominated as important and difficult.

|

Across the 20 interviews, a clear distinction arose between the issues that were most frequently mentioned in terms of actions being taken to fix them and the issues that were more often seen as difficult. Difficult issues were discussed as those that nobody really knew how to deal with or those that nobody was seriously doing anything about. The important/difficult distinction was very clear on the basis of both whether an issue was nominated as important or difficult, and also in terms of how the issue was spoken about.

Some quotes from the interviews give a flavour of how the different types of issues were discussed. The first, from a participant in the core group, describes an important issue:

Our main concerns are around emergency demand in hospitals and all indicators around that, ambulance bypass, around blockages in emergency departments, about the unprecedented growth in admissions through emergency departments …

The second, from a participant in the public health medicine group, describes a difficult issue:

… are we serious about inequalities or are we quite happy about them? … The whole indigenous health issue … the reality is we’re not serious about it … if we were we could do something about these things.

Finally, analysing the overall structure of the network, combined with who is discussing particular issues, generates an analysis of the link between network position and the distribution of issues. There is a high level of correspondence between an individual’s centrality in the network and the importance of that person’s issues compared with the overall ranking of issues. In other words, the most central people nominated the most frequently identified important issues. Those who were slightly less central tended to nominate the difficult issues. This suggests that which issues you are interested in is related to how central you are in a network. It is also apparent that which issues are being discussed relates to which sub-group you are part of. Full details of this analysis have been published elsewhere.8

Discussion

This study attempted to understand how perceived influence shapes the health policy agenda. It employed political science frameworks and combined an interest in influence and ideas as a means for examining the policy-making process. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in concert so that both influence and issues could be explored side by side and the relative prominence given to particular issues and the different modes of speaking about them understood.

Some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, it was based on perceptions of influence, not demonstrated influence. Second, it was a focused mapping of one locality of a network that had no boundaries, and not a sample across a network. A different starting point could generate a different network locale; however, the nomination of people in important positions suggests that it is representative of influence to some extent. Third, the lists of issues generated should not be taken to represent the health policy agenda in Victoria at this time. It does, however, provide insights into the link between influence and agenda setting, by mapping influential people, the issues they see as important and how they think about them, and the link between influence and issues.

This paper demonstrates the strength of an analysis that rests on strong theoretical and empirical foundations. It highlights the insights that can be gained from combining different theories and methods to analyse the policy process in public health. The quantitative component of this study (the blockmodelling) was able to provide insights into perceived influence, while the qualitative component (the interviews) provided information on the issues being discussed and how they were viewed by those working in this arena. Carrying out the first of these generates a picture of influence while the second points to important and difficult issues. Only together do they generate a picture of how the health policy agenda is shaped.

The fact that public health issues largely fell into the difficult basket has important implications for the public health agenda. Opportunities for policy change are greatest when new voices can be heard: for the agenda to change, patterns of influence must change. This analysis suggests that for a decisive shift towards an emphasis on prevention rather than cure, and for a focus on health inequalities, either newly influential actors with these as their main agenda items are required, or those who are already central will have to be convinced both of the need to place these higher on the agenda, and that they are not unachievable.

Finally, this study throws out a challenge to those working in public health to think about their level of engagement with the policy process, and strategies for improving that engagement, through coalition building and ongoing interactions with those who hold important policy-making positions.

Conclusion

The theoretical framework and the combination of methods used to examine influence in health policy demonstrate the link between networks, influence and agenda setting in health policy. Public health practitioners can use these findings to examine their own positions in influencing policy.

[1]

[2] Steinmo S, Watts J. It’s the institutions, stupid! Why comprehensive national health insurance always fails in America. J Health Polit Policy Law 1995; 20(2): 329–72.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | CAS |

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9] Lewis JM. Being around and knowing the players: networks of influence in health policy. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62 2125–36.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed |

[10]

[11] Brieger RL. Career attributes and network structure. A blockmodel study of a biomedical research specialty. Am Sociol Rev 1976; 41 117–35.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[12]