Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, July and August 2012

Communicable Diseases BranchHealth Protection NSW

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(10) 210-215 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12114

Published: 12 December 2012

| For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Public Health and then Infectious Diseases. The communicable diseases site is available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp. |

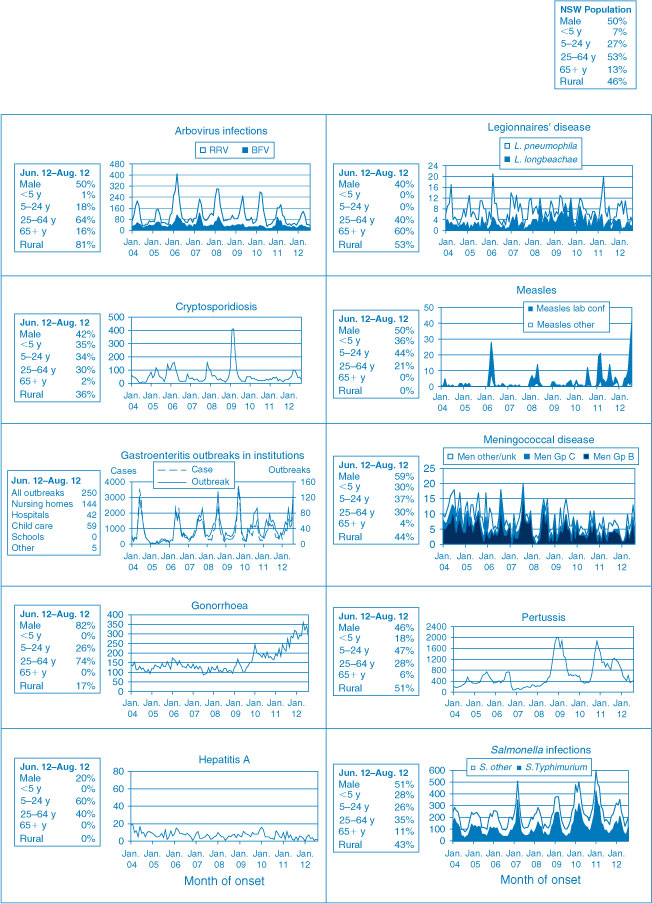

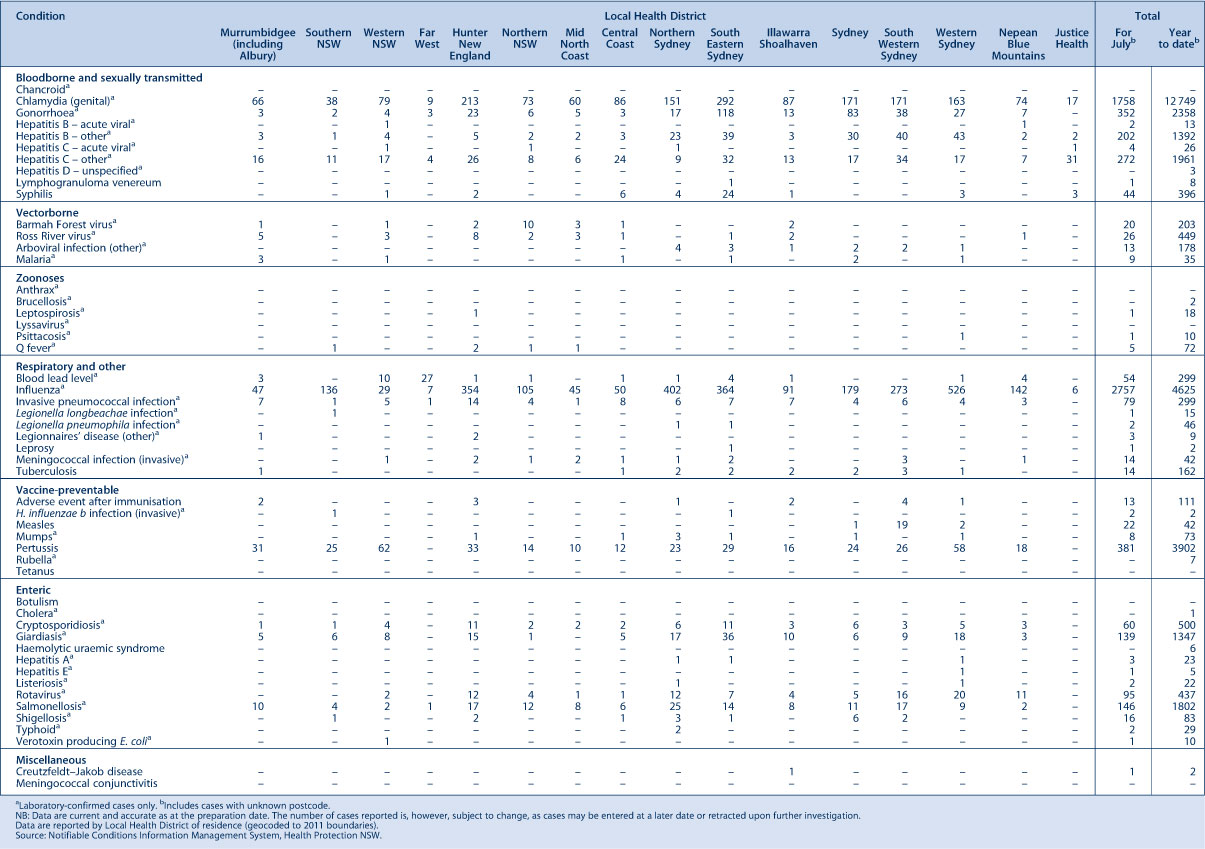

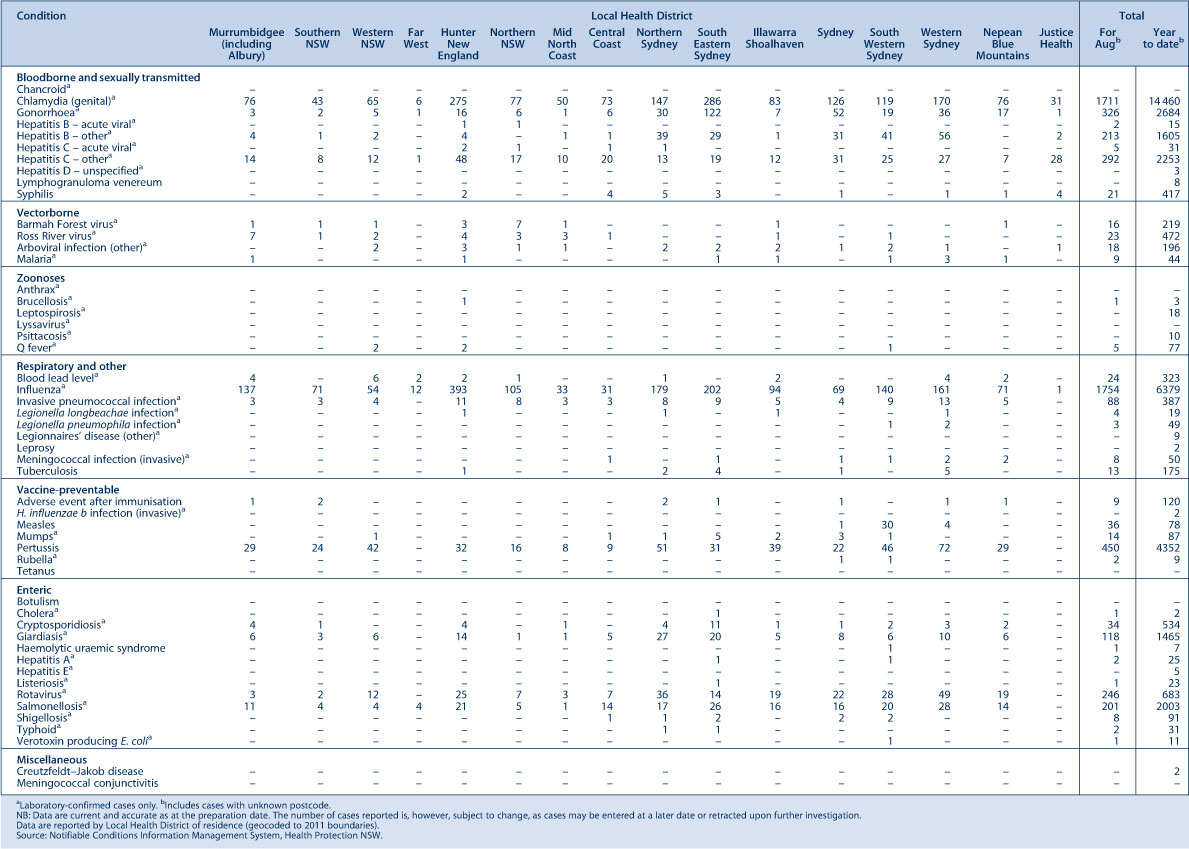

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show notifications of communicable diseases received in July and August 2012 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

Enteric infections

Outbreaks of suspected foodborne disease

Two of the nine complaints received by the NSW Food Authority about suspected foodborne disease in July and August 2012 were thought to be related to consumption of contaminated food. July and August was however a period of high levels of viral gastrointestinal disease in the community and most reports of suspected foodborne gastrointestinal illness in this period were, upon investigation, thought to be cases of viral gastrointestinal disease spread person-to-person.

In July, NSW Health was notified of cases of gastrointestinal illness in nine members of a group of 15 people who shared a meal at a restaurant in Sydney. Case-patients developed vomiting and diarrhoea 25 hours after the meal and their symptoms lasted between 8 and 44 hours. Public health unit staff interviewed 12 members of the group, six of whom were case-patients. Foods consumed included scallop soup, baked pie, cheese soufflé, lamb, eggnog (served in an egg shell), mulled wine and three desserts (plum pudding Alaska, pear and walnut truffle and raspberry macaroons). The group had also attended pre-dinner drinks together which included casual food (chips, dips, salad and cupcakes). On analysis, illness was not associated with the consumption of any food items. No stool specimens were submitted for testing. The NSW Food Authority inspected the premises based on the inclusion on the menu of raw egg food products that have a high risk for Salmonella contamination. The restaurant has subsequently taken extra steps to ensure food safety including sterilising the egg shells used in serving the eggnog and baking the meringue used in the Alaska dessert. The cause of the outbreak remains unknown.

In August, two separate groups of people reported illness following meals at a restaurant in Sydney on the same day. Four people in a group of seven, and six people in a group of eight, were affected with abdominal cramps and diarrhoea approximately 14 hours after eating at the restaurant. Symptoms lasted between 10 and 20 hours. No stool specimens were submitted for testing. The common ingredient eaten only by the case-patients and not by other members of the groups was a creamy mushroom sauce. The symptoms and duration of illness are suggestive of a bacterial toxin, however an environmental investigation was not possible as the restaurant was destroyed by fire soon after illness was reported.

Viral gastrointestinal disease

There were 188 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in an institution reported in July and August 2012, affecting at least 3684 people. The previous 5-year average for this period was 150 outbreaks. A total of 115 outbreaks occurred in aged-care facilities, 40 in child-care centres and 33 in hospitals. In the 138 outbreaks in which a stool specimen was collected, norovirus was confirmed in cases from 69 outbreaks and rotavirus was confirmed from 15.

There were 394 cases of rotavirus reported in July and August. This is the largest number of notifications for rotavirus since it became a notifiable condition in 2010. This increase is in parallel with increases in institutional outbreaks and presentations of gastroenteritis in emergency departments.

Respiratory infections

Influenza

Influenza activity, as measured by the number of people who presented with influenza-like illness to 59 of the state’s largest emergency departments, peaked in mid-July and has since continued to decline. In addition, the number of people who tested positive for influenza A by diagnostic laboratories decreased throughout July and August after a peak in late June. The number of patients who tested positive for influenza B increased over the same reporting period but is well below the peak reached in June.

In July, there were:

-

659 presentations to emergency departments (rate 3.3 per 1000 presentations)

-

1711 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza including:

-

-

1552 (91%) influenza A

-

159 (9%) influenza B.

-

In August, there were:

-

477 presentations (rate 2.4 per 1000 presentations)

-

1259 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza including:

-

-

915 (73%) influenza A

-

344 (27%) influenza B.

-

For a more detailed report on respiratory activity in NSW see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/Infectious/influenza_reports.asp

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Meningococcal disease

Twenty-two cases of meningococcal disease were notified in NSW in July and August 2012 (14 in July and eight in August), an increase from 15 notified in the same period in 2011. The age of the case-patients ranged from 3 months to 88 years and included five case-patients aged less than 5 years. The death of a 7-month old due to meningococcal disease serogroup B was notified in this period. Thirteen (59%) cases were due to serogroup B (for which there is no vaccine), three were due to serogroup Y, two (9%) were unable to be typed, and for three there was insufficient specimen collected. Of the 15 cases notified during the same period in 2011, 10 were due to serogroup B, two to serogroup W135, one to serogroup Y, and the remaining two were of an undetermined serogroup.

It is recommended that a single vaccine against meningococcal C disease be given to all children at the age of 12 months as well as persons at high risk of disease.1

Measles

Fifty-eight cases of measles were notified in NSW in July and August 2012; all were part of an ongoing outbreak that began in April. This was an increase compared to the 16 cases reported for the same period in 2011.

The age groups most affected were children aged 0–4 years (n = 25), of which 18 were infants aged less than 1 year, and young people aged 15–19 years (n = 11) and 10–14 years (n = 9). The average age of notified cases was 12.7 years (range: 4 months–41 years). Approximately half the case-patients were female (n = 28, 48%). Four (7%) case-patients were Aboriginal people, and all resided in Sydney South West Local Health District (LHD). Pacific Islander communities continue to be disproportionately affected.

Most cases were notified in the Sydney South West Local Health District (88%), followed by Sydney West (Parramatta) (10%) and Illawarra (2%) LHDs, with a concentration of cases from a small number of local government areas including Campbelltown and Liverpool.

Of the 58 notifications, 57 (98%) were laboratory confirmed. All specimens that were genotyped (n = 16) were measles virus genotype D8, indicating this outbreak is associated with the one measles importation from Thailand that was identified in April. Measles virus genotype D8 importations from Thailand in April have also been reported in Europe.2

The majority (90%) of the case-patients were not vaccinated for measles. Of the six case-patients that were reported to have been vaccinated, four were aged over 17 years and their vaccination status could not be verified on the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register; the other two case-patients were reported, based on parent recall, of having received one dose.

Two doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine are recommended for all children (at 12 months and 4 years of age),1 as well as all young adults planning international travel.

Pertussis

During July and August, 831 cases of pertussis were notified in NSW, less than half the number of cases notified for the same period in 2011 (n = 1966). Most case-patients were aged 5–9 years (n = 220), followed by the 0–4-year age group (n = 162) and the 10–14-year age group (n = 129). A 6-week old unvaccinated infant from the Illawarra died from pertussis infection in July.

Direct protection for young infants remains available through free vaccination for pertussis that is administered at 2, 4 and 6 months of age. The first dose can be provided as early as 6 weeks of age. There is also a booster dose at 3½ to 4 years. New parents and grandparents should also discuss the benefits of pertussis vaccination with their general practitioner.

Sexually transmissible infections and bloodborne viruses

Gonorrhoea

There were 678 cases of gonorrhoea notified in NSW in July and August 2012, an increase of 45% compared with the same period last year (n = 467). Most cases were notified in South Eastern Sydney LHD (35%) and Sydney LHD (20%) and 81% of case-patients were men.

People most at risk of gonorrhoea are men who have unsafe sex with men, and males and females who have unsafe heterosexual sex. NSW Health is working to enhance surveillance of the infection to better understand the mode of transmission, risk factors and testing patterns at a local level. Gathering further information will help inform campaigns promoting safer sex messages to high-risk communities.

References

[1] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2008.[2] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)-HCU-E editorial. Travellers returning with measles from Thailand to Finland, April 2012: infection control measures. Available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20184 (Cited 10 October 2012).