Year in review: health protection in NSW, 2011

NSW Ministry of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(8) 129-141 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12073

Published: 21 September 2012

Health protection involves the prevention and control of threats to health from communicable diseases and the environment. Health protection is achieved through a complex array of activities involving multiple agencies. Health protection activities include:

-

immunisation

-

the provision of safe environments including clean water, food and air

-

disease surveillance, epidemiological investigations, risk assessments, capacity building, quality assurance, providing expert advice

-

the development and application of legislation, regulations, policies and guidelines, distributing resources, and monitoring of program performance and outcomes.

In New South Wales (NSW) in 2011, these functions were carried out by a range of groups: at the Ministry of Health the Communicable Diseases Branch, the AIDS/Infectious Diseases Branch and the Environmental Health Branch; public health units within the local health districts; local government; other government agencies; and the community.

In this report we highlight the major health outcomes and achievements related to the health protection activities of NSW Health in 2011. The health outcomes described in this report are measured mainly through routine surveillance data that are derived from notifications of selected diseases provided by doctors, hospitals and laboratories to public health units under the former NSW Public Health Act 1991.*

The degree to which these notification data reflect the true incidence of disease varies between conditions, as many people with infectious disease will not be diagnosed with the disease or notified to public health units. However for some diseases, such as measles and tuberculosis, where a large proportion of people with the infection develop symptoms, present for health care and undergo confirmatory diagnostic testing soon after symptoms develop, notification data can come close to approximating the incidence of disease. For other conditions, such as hepatitis C, hepatitis B and chlamydia, where many people with the infection do not develop acute symptoms, and many acute infections are not diagnosed, notifications alone cannot be used to approximate the incidence of the disease.

Health outcomes related to environmental hazards (e.g. air pollution, poor water quality and poor housing) are harder to quantify. This is because a single environmental exposure may cause a number of different diseases and these diseases may also be caused by a number of other exposures. For example, particulate air pollution is known to cause heart disease, asthma and lung cancer. However, smoking, a high fat diet, allergies and infections may also cause these diseases. As a consequence, it is rarely possible to relate exposure to environmental hazards directly to health outcomes. Instead, hazards are monitored to identify and manage changes in population exposure. For example, the Environmental Health Branch maintains a comprehensive drinking water quality monitoring system and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage maintains a network of air quality monitors.

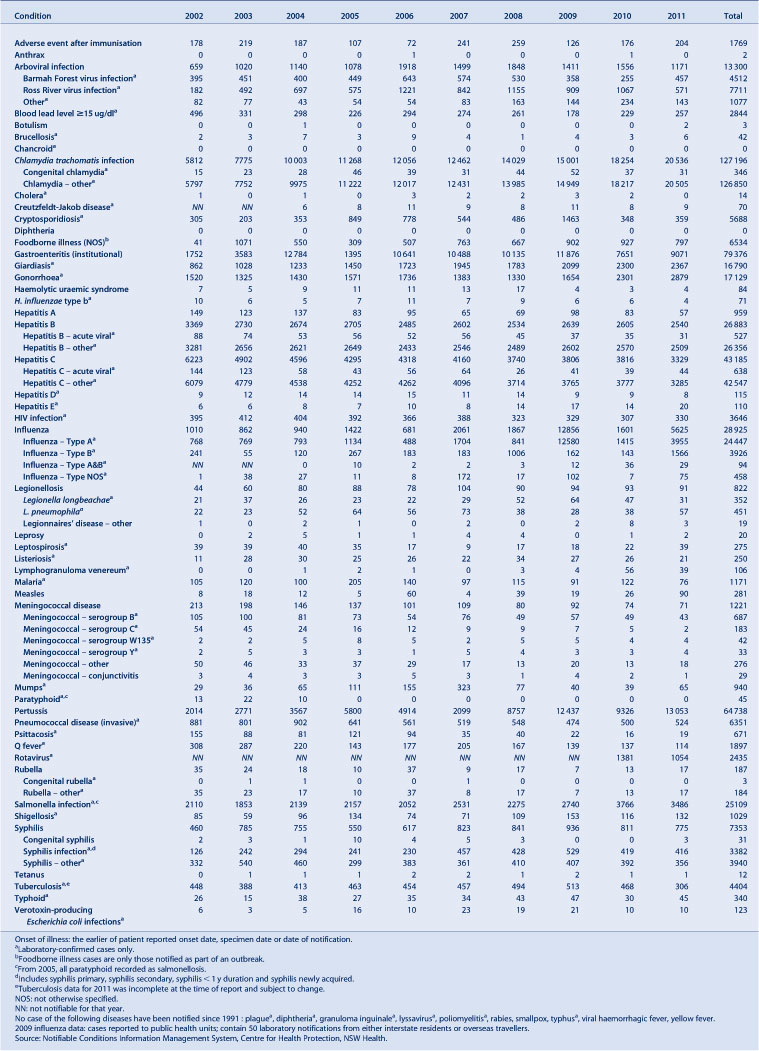

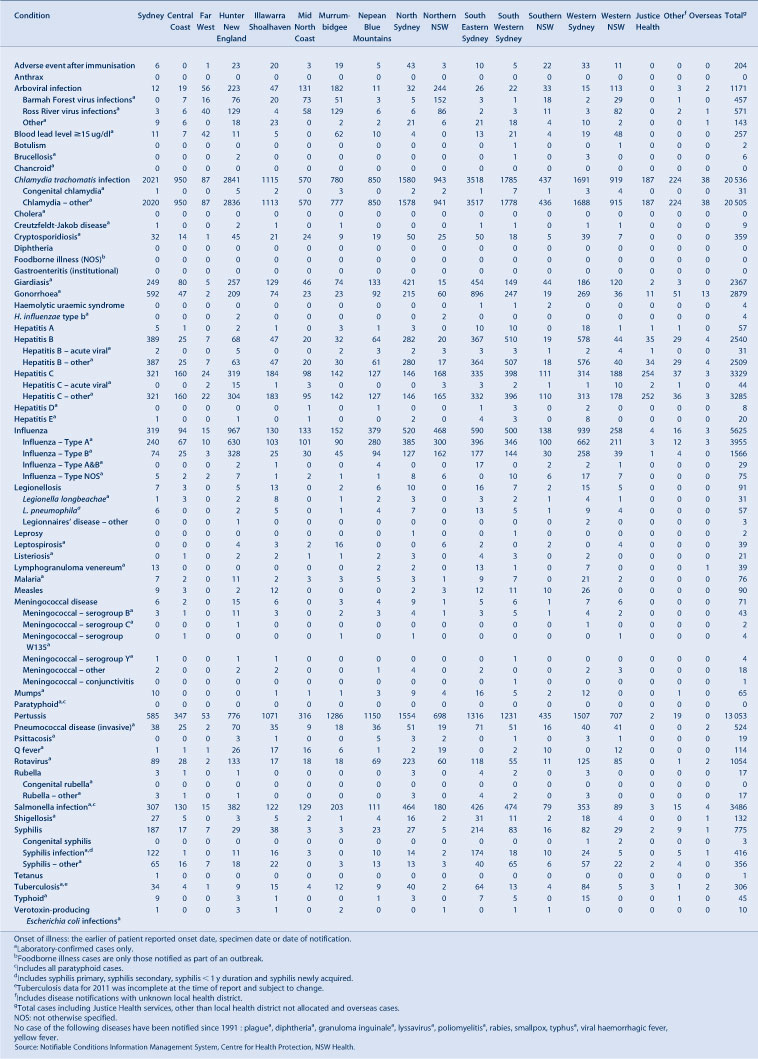

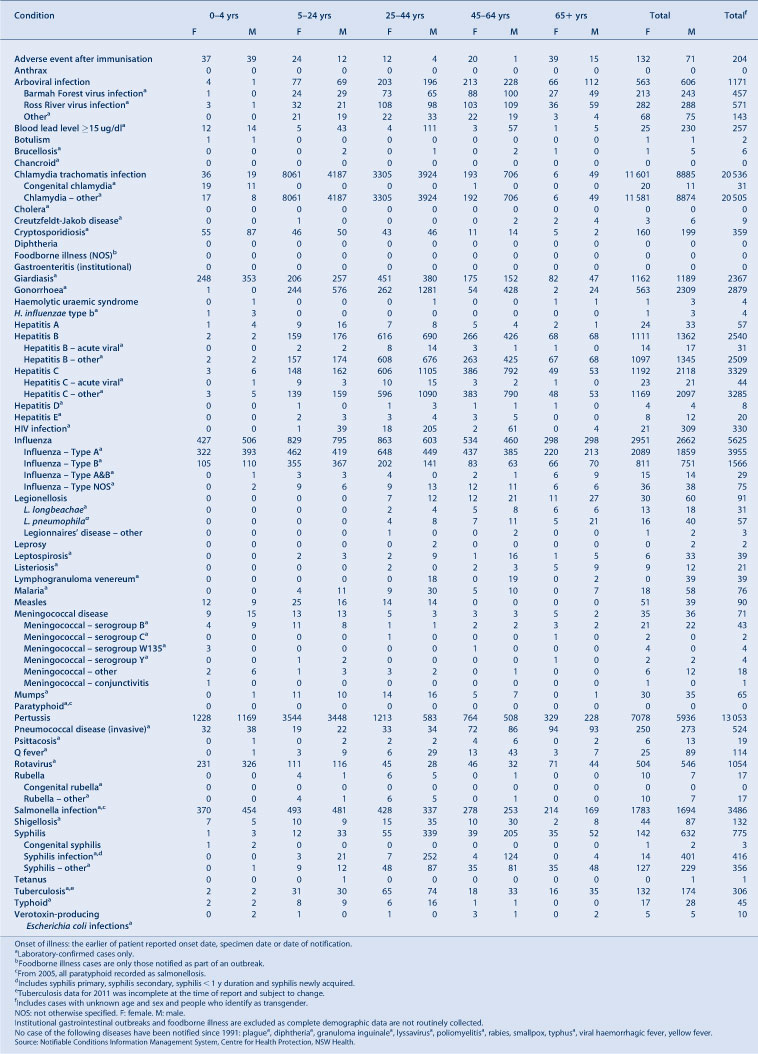

Tables 1–6 summarise disease-specific data on notifiable conditions reported by: year of onset of illness; month of onset of illness; local health district; age group; and sex.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Notification data

In 2011 there were:

-

over 13 000 pertussis case notifications, a record number, mostly in 5–9-year old children (over 4000 notifications), followed by 0–4-year old children (over 2400) and 10–14-year olds (over 2300). There was considerable variation in pertussis notification rates between local health districts. The pertussis epidemic highlights the difficulty in controlling this vaccine-preventable disease. While notification rates were the highest on record, it is unclear to what extent this high rate is due to waning immunity, enhanced identification through better laboratory diagnosis, greater clinician awareness or whether other factors are at play

-

90 measles case notifications, of which nine (10%) were imported from overseas and the remainder were either linked to these cases or locally acquired. Two of the larger clusters of cases of measles were identified in schools within the boundaries of the Western Sydney and Greater Southern Local Health Districts. One case of measles encephalitis was reported. The number of measles cases reported in 2011 was the highest on record since 1998, the year of the Australian Measles Control Campaign. The immunisation of international travellers and immigrant groups with low immunisation rates should remain a key feature of the vaccine-preventable disease control strategies

-

71 meningococcal disease case notifications, the lowest number in recent years. Of these, 43 were due to serogroup B (61%), four were due to serogroup W135 (6%) and another four serogroup Y (6%); only two were due to serogroup C (3%) and 18 were caused by an unknown serogroup (25%). The two cases of meningococcal C disease were both in adults. Meningococcal notifications have been declining for more than a decade, mostly for meningococcal C disease for which a vaccine was introduced in 2003

-

65 mumps case notifications, an increase from the 39 reported in 2010. The highest monthly notifications were reported in December (n = 11), the most reported in any month since February 2008

-

524 invasive pneumococcal disease case notifications compared with 504 notifications in 2010. Serotype 19A was identified as the cause of infection in 56% of cases in children under 5 years of age and in 24% of the other case-patients.

Prevention activities

Highlights for infant immunisation in 2011 included:

-

immunisation rates for children and adolescents remained high, with NSW reaching coverage benchmarks of 90% for children at 1 and 2 years of age, with an increase in coverage at 5 years of age to just below 90%

-

immunisation coverage for Aboriginal children improved in the 2- and 5-year age groups.

Further work is required to improve coverage rates for Aboriginal children in the 1-year age group (Table 7).

|

In 2011, the NSW School-Based Vaccination Program vaccinated:

-

77% of Year 7 and 66% of Year 10 students with a booster dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine

-

81% of Year 7 girls with at least one dose of human papillomavirus vaccine and 71% of Year 7 girls with three doses of the vaccine

-

68% of Year 7 children with at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine and 63% of Year 7 children with two doses of the vaccine (hepatitis B vaccination is only offered to children who have not previously received a full course)

-

45% of Year 7 children with varicella vaccine (varicella vaccination is only offered to children without a history of infection or vaccination).

These data do not include children who received these free vaccines from general practitioners (GPs) or other immunisation providers.

Initiatives to improve vaccination coverage in 2011 included:

-

the introduction into the routine immunisation schedule of a 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine and implementation of a supplementary dose program for children who had received three doses of the 7-valent vaccine

-

the continued provision of free pertussis vaccine for new parents, grandparents and other adults who regularly care for infants under 12 months of age, in an effort to indirectly protect those babies in light of the ongoing pertussis epidemic

-

the development of strategies and health-system capacity to follow-up Aboriginal children who are overdue for vaccination

-

the provision of free measles-mumps-rubella vaccine to unvaccinated people born in or since 1966 and to contacts of people with measles, to prevent further transmission in the community

-

working with Divisions of General Practice, local councils and community health centres to improve coverage in areas of low vaccination coverage.

Bloodborne viruses

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

a stable number of total hepatitis B case notifications (n = 2540); 51% were in people aged 25–44 years (total notifications are mainly of people whose time of infection is unknown). However the number of hepatitis B notifications thought to be newly acquired has steadily declined over the last 5 years, from 56 reported in 2007 to 31 in 2011

-

a slight decrease in hepatitis C case notifications (3329 notifications, down from 3816 in 2010). Case-patients were most commonly men aged 25–44 years (33%), men aged 45–64 years (24%) and women aged 25–44 years (18%). The number of notifications of newly acquired hepatitis C infections remained stable (n = 44, compared with 39 in 2010; the annual average over the previous 5 years is 45)

-

a slight increase in case notifications of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with 330 reported in 2011 (compared to 307 in 2010). The age groups most affected were those aged 30–39 years (n = 123; 37%) and 20–29 years (n = 90; 27%). In 2011, 277 notifications (84%) were reported to be homosexually acquired.

Improvements in methods for data cleaning have identified duplicate notifications for hepatitis B and C cases, resulting in a more accurate count of cases and a reduction in the overall number of notifications for previous years, particularly for before 2005.

Prevention activities

NSW Health has a range of policies and strategies in place to control the spread of HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C, including regular campaigns to promote safer sex, needle and syringe programs to provide sterile equipment to injecting drug users, and support of the management of patients with sexually transmissible infections and hepatitis C. Highlights in 2011 included:

-

ACON (formerly the AIDS Council of NSW) developed an HIV prevention campaign for gay men called The Big Picture (www.hivthebigpicture.org.au), designed to inform gay men in NSW about the risks for HIV transmission. It also offered the gay community strategies for keeping infection rates low: maintain condom use, increase HIV testing, encourage the disclosure of HIV status and restrict sex without condoms to men of the same HIV status

-

the NSW Expanded Medication Access Scheme for HIV Section 100 drugs (Highly Specialised Drugs Program) to provide people with HIV with improved access to treatment in NSW. This scheme was developed in light of both long-standing and recent evidence of the effectiveness of HIV antiretroviral therapy in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. 1 Under the new Scheme, patients who are stable on their medications and meet certain criteria can elect to have their medication delivered to any address of their choosing rather than attend a hospital pharmacy. A number of select retail pharmacies also operate as pick up locations for patients

-

NSW publicly funded HIV and sexual health clinics provided 79 046 occasions of services to 6536 clients related to HIV treatment, management and care (an increase of 2.2% of occasions of services and 1.0% of clients compared with 2010)

-

the first phase of a hepatitis C prevention campaign, aiming to increase awareness of the transmission and prevention of hepatitis C for young people. Brochures and posters were distributed to 750 general practices in NSW. In 2010/11, the NSW Needle and Syringe Program comprised over 940 outlets (332 public sector outlets, 159 dispensing machines and 450 pharmacies)

-

Approximately 9.98 million needles and syringes were dispensed and over 13 400 referrals were provided to drug treatment services, hepatitis services and other health and welfare agencies for people who inject drugs

-

3014 patients with hepatitis C were referred for hepatitis C assessment, 1062 patients initiated treatment and 989 patients completed treatment.

Sexually transmissible infections

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

a similar number of infectious syphilis case notifications compared with recent years (416, compared with 419 in 2010, and a 5-year average of 412)

-

a decrease in the number of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) case notifications (39, compared with 56 in 2010). All notifications were reported in males, and 37 (95%) case-patients were aged between 25 and 64 years. The number of notifications decreased in late 2010 following an outbreak earlier in that year. The outbreak in NSW occurred within the global context of increased European rates of LGV infection in men who have sex with men 2

-

a continued increase in the number of chlamydia case notifications (20 536, up 13% from 18 254 in 2010); 57% of cases notified were female and 59% of cases were aged between 15 and 24 years

-

an increase in the number of gonorrhoea notifications (2879, up 26% from 2301 in 2010). Men made up 80% of cases and 54% of these case-patients were aged 25–44 years.

Overall, notifications of sexually transmissible infections (STIs) in NSW continue to rise with chlamydia continuing to be the most commonly notified STI in NSW. Much of the increase in chlamydia and at least some of the increase in gonorrhoea notifications may relate to increased screening and case detection.

Prevention activities

Highlights in 2011 included:

-

the NSW STIs in Gay Men Action Group (STIGMA) (a partnership of state and local prevention agencies based in central and south eastern Sydney) developed educational resources for updating GPs on recent research and epidemiology of STIs. STIGMA also distributed a campaign aimed at gay men promoting testing for STIs and contact tracing, based around the National Gay Men’s Syphilis Action Plan: http://stigma.net.au/resources/National_Gay_Mens_Syphilis_Action_Plan.pdf

-

NSW Health continued the second phase of the successful 2009 HIV and STI education campaign, Get Tested, Play Safe: http://www.gettested.com.au. The aim of the campaign was to reinforce STI awareness, increase testing and improve safer sex behaviour among young people. Television, radio, online and print advertising was used statewide and pilot partnerships with music festivals extended the reach of the campaign

-

the NSW STI Programs Unit developed a Sexually Transmissible Infections Contact Tracing Tool for use in general practice. Copies were distributed to all GPs in NSW, and through the NSW Public Health Bulletin to selected local health districts. 3 The Tool is a quick reference guide to assist doctors to understand their contact tracing responsibilities, the steps involved in best practice contact tracing, and key points for the management of STI contacts. For more information see: http://www.stipu.nsw.gov.au/content/Image/May_2011_Contact_tracing_tool_final_version.pdf

-

publicly funded sexual health clinics provided 25 851 occasions of service (an 8.2% increase compared to 2010) related to STI treatment, management and care, providing services to 12 930 clients (a 3.3% increase compared to 2010).

Enteric diseases (infectious, food and water)

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

a 15% increase in enteric disease case notifications (6484) compared with the average annual count for the previous 5 years

-

a 31% increase in salmonellosis case notifications (3486) compared with the annual average for the previous 5 years. The increase was in part explained by an ongoing increase in Salmonella Typhimurium 170 infections, a serovar previously associated with the consumption of contaminated eggs

-

a decrease in the reports of outbreaks of probable foodborne disease (47 outbreaks affecting 797 people, compared with 59 outbreaks affecting 728 people in 2010)

-

a stable number of reports of outbreaks of probable viral gastroenteritis in institutions (525 notifications affecting 9071 people, compared with 518 outbreaks affecting 9359 people in 2010)

-

10 point-source outbreaks of Salmonella Typhimurium, most likely associated with the consumption of sauces and desserts prepared with raw eggs.

Prevention activities

NSW Health works with OzFoodNet nationally and the NSW Food Authority locally to investigate and control foodborne outbreaks and food-contamination incidents, and to make prevention recommendations.

NSW Health is the public health regulator of major water utilities through operating licences and memoranda of understanding (Hunter Water Corporation, Sydney Water Corporation and Sydney Catchment Authority). In 2011 the Water Unit and public health units worked with these utilities to:

-

ensure compliance with relevant guidelines including the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines 4 and the Australian Guidelines for Water Recycling 5

-

monitor compliance of utilities with the NSW Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act 1957.

The Water Unit and public health units also exercise public health oversight of more than 100 water utilities in regional NSW through the NSW Health Drinking Water Monitoring Program, 6 which provides guidance on drinking water monitoring and is supported by NSW Health laboratories. In 2011 regional sampling compliance was very good with:

-

97% of expected microbiological samples taken (compared with 96% in 2010)

-

100% of expected chemistry samples taken (the same as in 2010).

NSW Health has commenced a major upgrade of the web-based NSW Drinking Water Database that will help water utilities and public health units better manage drinking water quality. NSW Health is also supporting rural water utilities to develop risk-based drinking water management systems, which will be required under the Public Health Act 2010. In 2011, NSW Health helped four small water utilities develop management systems that will help ensure the safety of the drinking water supply. More water utilities will receive assistance in 2012.

NSW Health is responsible for reviewing licence applications from private recycled water or drinking water suppliers under the Water Industry Competition Act 2006. In 2011, the Water Unit and public health units:

-

reviewed 14 licence applications for recycled water

-

advised local councils and the NSW Office of Water on more than 20 new and ongoing recycled water schemes regulated under the Local Government Act 1993.

Respiratory disease (infectious and environmental)

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

an increase in the number of Legionnaires’ disease case notifications due to Legionella pneumophila (57 compared to 38 cases in 2010). Public health investigations did not identify a common source for these cases

-

L. pneumophila cases peaked in April 2011 with 20 cases reported. Public health officers worked closely with local councils at this time to inform owners of registered cooling towers (one possible source of L. pneumophila bacteria) on the need to comply with regulations to minimise the risk of Legionella contamination. A statewide media release was also issued in May 2011 to reinforce this message

-

an increase in the number of notifications of influenza (5625 compared to 1601 notifications in 2010). As only laboratory confirmed cases of influenza are notifiable and only a very small proportion of all people with influenza are tested, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the true level of influenza activity in the community based on these data. There were at least 61 admissions to intensive care units for treatment of influenza-associated illnesses

-

a cluster of influenza isolates resistant to influenza antiviral medications. Routine resistance testing of a selection of NSW influenza A samples detected 31 influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus isolates with the H275Y neuraminidase mutation associated with resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir. None of these showed resistance to zanamivir. Of these isolates, 29 were collected from patients in the Hunter region whose ages ranged from 4 months to 58 years, and included three pregnant women. Of these case-patients, six required hospitalisation. There were no deaths.

-

a decrease in the number of notifications of tuberculosis (306 compared to 468 cases in 2010). At the time of this report the tuberculosis data for 2011 remained incomplete. Five cases of multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB) were identified, a similar number as in previous years (five in 2010 and 10 in 2009).

Prevention activities

Highlights in 2011 included:

-

a campaign that focused on three respiratory disease prevention messages: Cover your face when you cough or sneeze; Wash your hands; and Stay at home if you're sick so you don't infect others. The campaign included radio advertising, advertisements on public transport, digital media and the distribution of The Spread of Flu is Up to You posters

-

seasonal influenza vaccine provided free under the National Immunisation Program for people at high risk of severe influenza complications. The NSW Health Population Health Survey estimated that 32% of all respondents (95% confidence interval [CI]: 30–35) interviewed during August and September 2011 had received a seasonal influenza vaccine in the previous 12 months, a slight increase in vaccine uptake compared to the estimate for the same period in the previous year (29% [95% CI: 27–32]). For respondents aged 65 years and over (one of the identified high-risk groups), the estimated vaccination rate was 73% (95% CI: 69–77), which is similar to the rate for previous years.

Vectorborne diseases

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

a decrease in Ross River virus infection notifications (571, a 46% decline compared with 1067 in 2010)

-

an increase in the number of Barmah Forest virus infection notifications (457, 79% higher than the 255 notified in 2010)

-

two confirmed cases of locally acquired Murray Valley encephalitis, from the Western NSW and Hunter New England Local Health Districts, the first reported cases since 2008

-

one Kunjin virus infection case notification, probably acquired in the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, the first NSW case notified since 2001

-

a 40% decrease in the number of dengue fever case notifications in 2011 (130 compared with 218 in 2010). All of the dengue fever cases in 2011 were linked to international travel, with travel to Indonesia the most commonly reported exposure site (48%), followed by Thailand (10%), India and the Philippines (both 8%). While there is no local transmission of dengue fever in NSW, it is the most common mosquitoborne viral disease in humans worldwide, and represents a major international public health concern

-

a 38% decrease in the number of malaria case notifications (76, compared with 122 in 2010). Travel to Papua New Guinea was the most commonly reported exposure site (25%), followed by India (13%) and Ghana (11%).

The NSW arbovirus surveillance program includes: mosquito trapping and the monitoring of virus activity in mosquito populations; and, monitoring for antibodies to Murray Valley encephalitis and Kunjin virus infection in sentinel chicken flocks located in a number of strategic sites in rural NSW from mid-spring to mid-autumn when transmission of arbovirus infections is most common.

With increasing international travel, exotic mosquitoborne diseases such as dengue fever, malaria and chikungunya will pose an ongoing risk for people travelling to endemic areas. International trade also increases the risk of the importation of exotic mosquito species which are able to transmit these infections locally.

Prevention activities

-

In 2011 statewide media releases warning about the increased risk of mosquitoborne infections and how to prevent them were issued in February, March, April and December. These were supplemented by a Fight the Bite public education campaign in high-risk districts incorporating radio advertising, the distribution of posters and brochures, and a range of local media messaging by Public Health officials. See http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/publichealth/environment/hazards/pdf/ftb_hr_cl.

Zoonotic diseases

Notification data

In 2011 there was:

-

a modest decrease in Q fever case notifications (114 compared with 137 in 2010). Q fever was the most commonly notified zoonotic disease in 2011 (114 case notifications)

-

a slight increase in brucellosis infections (six, compared with three in 2010). Three cases were acquired overseas, two infections were in feral pig hunters in northern NSW and the source of one case was unknown

-

no human case of Hendra virus infection in humans, despite 10 fatal cases in horses in northern NSW. NSW Health worked closely with the North Coast Public Health Unit and the Department of Primary Industries to investigate and control outbreaks and prevent infection in humans.

Environmental exposures and risk assessment

On 8 August 2011, an accident at the Orica ammonium nitrate plant on Kooragang Island, Newcastle, resulted in the deposition of a chemical called hexavalent chromium on an area of Stockton that lay directly downwind of the plant. Hunter New England Population Health and the Ministry of Health’s Environmental Health Branch, assisted by an expert panel, assessed the health risks associated with this event, provided health information to the public and advice to other agencies on matters such as the cleanup of the chemical deposition. As a result of this incident, a number of changes have been made to strengthen the NSW Government response to pollution incidents. First, the Environment Protection Authority has been reconstituted as an independent entity. Second, several amendments have been made to the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 2007. An important change is that polluters are now required to notify NSW Health immediately of any incidents causing, or threatening to cause, material harm to the environment.

Aboriginal health

NSW Housing for Health

Housing for Health is an evidence-based housing repair and maintenance program that focuses on improving the safety and health of residents. 7 Since 1998, over 11 500 Aboriginal people living in nearly 2600 houses in 78 Aboriginal communities have benefited from the Housing for Health program. Nearly 75 000 items that relate to improved safety and health have been repaired through the program. An evaluation of the NSW Housing for Health program found that populations exposed to the program were 40% less likely to be hospitalised with infectious diseases compared with the rest of the rural NSW Aboriginal population. 8

In 2011 the Housing for Health program:

-

completed projects in Bourke, Enngonia, Wilcannia, La Perouse and Coffs Harbour. The Coffs Harbour project was a trial program with the Aboriginal Housing Office and Housing NSW to integrate Housing for Health with the broader Aboriginal Housing Office Backlog and Maintenance Program

-

commenced new projects in Purfleet and Walhallow.

Aboriginal Communities Water and Sewerage Program

Clean water and functioning sewerage systems are a prerequisite for good health. Widespread availability of these essential services improves health by reducing communicable diseases such as skin infections and diarrhoeal illness. The Aboriginal Communities Water and Sewerage Program is a joint partnership between the NSW Government and the NSW Aboriginal Land Council. 9 The Program aims to ensure adequate operation, maintenance and monitoring of water supplies and sewerage systems in more than 60 Aboriginal communities in NSW. NSW Health is involved in the development and implementation of the Program.

In 2011:

-

a further seven Aboriginal communities with a combined population of around 1000 people began receiving improved water and sewerage services, bringing the total to 38 communities of over 4000 people who have received improved water and sewerage services under the Program. Public health units are working with communities, the NSW Office of Water, local water utilities and service providers to implement Risk-Based Water and Sewerage Management Plans

-

an Aboriginal traineeship has been approved by the Aboriginal Communities Water and Sewerage Program steering committee to ensure that Aboriginal people obtain the necessary skills for employment with local water utilities. Funding of $66 000 each year for the next 2 years will be spent for training eight Aboriginal people. This initiative is being managed by Aboriginal Affairs NSW.

The Aboriginal Environmental Health Officer Training Program

The Aboriginal Environmental Health Officer Training Program aims to increase opportunities for workforce participation by Aboriginal people and enhance the involvement of Aboriginal people in improving environmental health outcomes. The Program also contributes to addressing current workforce shortages in environmental health. Since 1998, 11 Aboriginal Environmental Health Officers have graduated from the Program.

In 2011:

-

seven Aboriginal Environmental Health Officer Trainees were participating in the Program. The percentage of Aboriginal people employed within the NSW Health Environmental Health workforce increased from 0% (n = 0) in 1998 to over 20% (n = 12) in 2011. The program is now being expanded in partnerships with Local Government to increase Aboriginality in the overall NSW environmental health workforce (much of which is based in Local Government)

-

four new trainee positions were created under funding agreements between the Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit, regional public health units and Local Governments.

Negotiations are in place for further Local Government trainee positions which will start during 2012.

Acknowledgment

Protecting the health of the community is a collaborative effort, involving public health units, clinicians, laboratory scientists, affected communities, and other government and community-based organisations. We thank all those involved for the role they played in NSW in 2011.

References

[1] Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365 493–505.| Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC3MXhtVars7jF&md5=f0fee1a1e1b9c2d529492d0aaa5a7cb8CAS |

[2] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Sexually transmitted infections in Europe, 1990–2009. Stockholm: ECDC; 2011. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/110526_SUR_STI_in_Europe_1990-2009.pdf (Cited 18 April 2012).

[3] Burton L, Murray C. Introducing a new sexually transmissible infections contact tracing resource for use in NSW general practice. N S W Public Health Bull 2011; 22 164

| Introducing a new sexually transmissible infections contact tracing resource for use in NSW general practice.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[4] National Health and Medical Research Council and Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council. Australian drinking water guidelines Paper 6. National water quality management strategy. Canberra: NHMRC, NRMMC, Commonwealth of Australia; 2011.

[5] Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council. Environment Protection and Heritage Council; Australian Health Ministers’ Conference. National water quality management strategy. Australian guidelines for water recycling: managing health and environmental risks (Phase 1). November 2006. Available at: http://www.ephc.gov.au/sites/default/files/WQ_AGWR_GL__Managing_Health_Environmental_Risks_Phase1_Final_200611.pdf (Cited 18 April 2012).

[6] NSW Health. Drinking water monitoring program. December 2005. State Health Publication No: (EH) 050175. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2005.

[7] NSW Health. Housing for Health [internet]. Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/environment/aboriginal/housing_health.asp (Cited 3 May 2011).

[8] NSW Health. Closing the gap: 10 years of housing for health in NSW. An evaluation of a healthy housing intervention. Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2010/pdf/housing_health_010210.pdf (Cited May 2011).

[9] NSW Aboriginal Land Council and NSW Government. Aboriginal Communities Water and Sewerage Program [internet]. Available at: http://www.water.nsw.gov.au/Urban-water/Aboriginal-communities/default.aspx (Cited 8 May 2011).

* The Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) (http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/phact/)

The Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) was passed by the NSW Parliament in December 2010 and commenced on 1 September 2012. The Public Health Regulation 2012 was approved in July 2012 and commenced, along with the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW), on 1 September 2012. The objectives of the Regulation are to support the smooth operation of the Act. The Act carries over many of the provisions of the Public Health Act 1991 (NSW) while also including a range of new provisions.