Guarding against an HIV epidemic within an Aboriginal community and cultural framework; lessons from NSW

James Ward A B , Snehal P. Akre A and John M. Kaldor AA National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, University of New South Wales

B Corresponding author. Email: jward@nchecr.unsw.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 21(4) 78-82 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB10015

Published: 27 May 2010

Abstract

The rate of HIV diagnosis in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in Australia has been stable over the past 5 years. It is similar to the rate in non-Indigenous people overall, but there are major differences in the demographical and behaviour patterns associated with infection, with a history of injecting drug use and heterosexual contact much more prominent in Aboriginal people with HIV infection. Moreover there are a range of factors, such as social disadvantage, a higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections and poor access to health services that place Aboriginal people at special risk of HIV infection. Mainstream and Aboriginal community-controlled health services have an important role in preventing this epidemic. Partnerships developed within NSW have supported a range of services for Aboriginal people. There is a continuing need to support these services in their response to HIV, with a particular focus on Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers, to ensure that the prevention of HIV remains a high priority.

For over two decades, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been recognised through national and jurisdictional level strategic documents as being potentially at increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 The risk factors for this include poorer access to health services, and higher rates of numbers of other health conditions, particularly bacterial sexually transmissible infections (STIs).2–8

Aboriginal people of New South Wales (NSW) represent 29% of the national Indigenous population, the largest proportion of any jurisdiction.4 Within NSW, Aboriginal people are recognised as experiencing much of the same social and health disadvantages as the rest of Indigenous Australia.4 These include, but are not limited to, lower life expectancy, more underlying and complex health needs, higher unemployment levels, lower education attainment and a higher proportion of the population resident in outer regional and remote locations.4 Furthermore the Aboriginal population is younger and its overall size is growing faster than the non-Aboriginal population.3,4

In this paper we: review the national epidemiological status of HIV in Aboriginal communities as well as the factors that may increase the risk of HIV infection within this population; discuss the NSW strategic response, with particular reference to health service providers; and describe the opportunities for enhancing the response to guard against a HIV epidemic in Aboriginal communities.

National epidemiological situation

Each year since 2007, a comprehensive report has been produced on the epidemiological status of bloodborne viral and sexually transmissible infections, including HIV, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.7,9,10 The report is largely based on routine notifiable disease reports, but also includes data from a range of other sources.

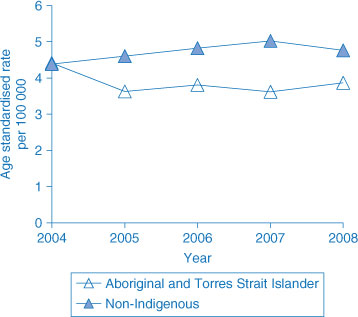

The rate of HIV notification in the Aboriginal population nationally has remained relatively stable at around 4.0 per 100 000 over the last 5 years, similar to the non-Indigenous community (Figure 1).8 Each year, nationally around 20 diagnoses of HIV are reported among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, compared to around 1000 in Australia as a whole. Of all HIV diagnoses in the Indigenous community in Australia, 30.1% have been notified in NSW.8

|

Over the last 5 years, the rate of HIV diagnoses in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians has been similar. However, there are some important differences between the two populations in terms of demographics and how people have acquired HIV. Compared with non-Indigenous Australians, HIV is diagnosed more often in women (22% versus 6%), and is diagnosed at a younger age (median age 33 years versus 37 years).

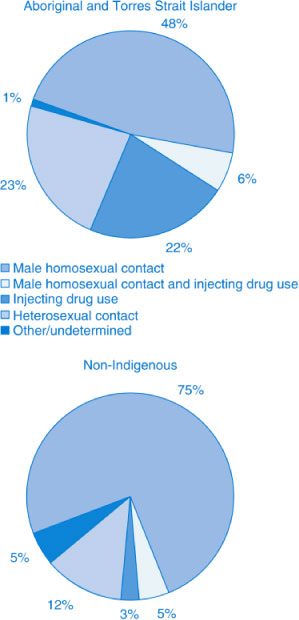

With regards to transmission patterns (Figure 2), male-to-male sex is reported at lower rates in the Indigenous diagnoses (48% versus 75%), while heterosexual transmission is reported more frequently (23% versus 12%), and a history of injecting drug use is recorded at seven times the rate among the Indigenous cases (22% versus 3%).7 When injecting drug use and sexual transmission risk factors are combined, there is a sharp contrast between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cases. Among Indigenous cases, heterosexual contact inclusive of injecting drug users are reported among 45% of cases (compared to 15% of non-Indigenous cases), while homosexual contact and injecting drug users in the Aboriginal population is reported among 54% of cases compared to 80% of cases in the non-Indigenous population. This highlights the potential for escalated transmission within the Aboriginal community.

|

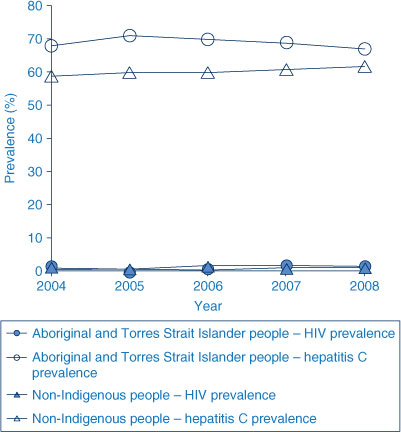

The higher proportion of cases that are related to injecting drug use could indicate that unsafe injecting is more common among Aboriginal people, or that Indigenous people who inject drugs have poorer access to harm reduction services (Figure 3). A higher per capita rate of hepatitis C notification supports both possibilities, as there is a very strong association between hepatitis C infection and injecting drug use. The annual survey of people attending needle and syringe programs recruits a high proportion of Aboriginal people (around 10%, compared to 2.5% in the population of Australia as a whole), perhaps due in part to the location of survey sites.8 For people who inject drugs, harm reduction has been highly effective as a means of preventing HIV infection,11 but needs to be strengthened for Aboriginal people.

|

Men who have sex with men represent just under 50% of all notifications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the last 5 years.7,8 This group is also the most affected by HIV infection in non-Indigenous Australians.7,8 The public health response to HIV in this group has been sophisticated and sustained over several decades, largely facilitated through the AIDS Councils in the jurisdictions.

Within the Aboriginal population, several other groups are at risk of HIV infection but do not benefit from such a comprehensive prevention framework. The higher proportion of HIV acquired through heterosexual sex in the Aboriginal population indicates the potential for increased transmission to a much larger group.7,8,12

Risk factors for HIV transmission in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

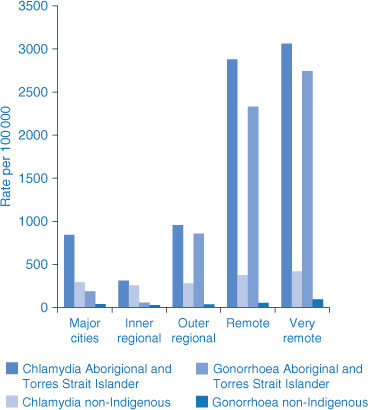

A number of factors have the potential to substantially increase HIV transmission rates within the Indigenous population of Australia. Elevated rates of bacterial sexually transmissible infections are well documented,3,5–8 and evidence is emerging of high rates of viral sexually transmissible infections such as HSV-2.13 Both bacterial and viral sexually transmissible infections are known to potentiate the transmission of HIV.14,15 Chlamydia, gonorrhoea and infectious syphilis are reported at rates that are respectively 5, 34 and 4 times greater than those in non-Indigenous communities, with the differential particularly pronounced in remote communities (Figure 4).7,8 The evidence to support sexually transmissible infections treatment as a means of reducing HIV infection rates is not strong, but the converse is clear: populations with high sexually transmissible infection rates are vulnerable to HIV transmission, because these infections are either markers of risk, or potentiators of disease.14,15

|

As HIV infection can remain asymptomatic for years, people at risk need to be actively engaged with health services to ensure that they have access to services for prevention, diagnosis and treatment if needed.3 However several factors work to compromise Aboriginal populations’ access to sexual health and HIV-related services.16 These factors include the perceived loss of confidentiality and privacy, the stigma associated with HIV, absence of relevant services in parts of NSW, the lack of availability of transport to specialist services, and the cultural appropriateness of services and service delivery.3,17 Other factors that increase the vulnerability of the Aboriginal population include the higher proportion of youth, alcohol and other drug use, higher levels of imprisonment; and lower levels of health literacy.1,3

Strategic response to HIV among Aboriginal people in NSW: roles and responsibilities

Responding to HIV in Aboriginal people is not simple. The response demands a comprehensive partnership between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and government, taking particular account of emerging epidemiological trends.

This collaborative approach is exemplified by the NSW Aboriginal Health Partnership between the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (AH&MRC), the peak organisation for Aboriginal community-controlled health services and the NSW Department of Health. Through this partnership, the AH&MRC and its member services have played a central role in the planning and delivery of key initiatives related to HIV, sexual health and bloodborne viral infections. Among the most significant programs have been the: establishment of the Aboriginal Sexual Health Advisory Committee (ASHAC); conduct of two major social marketing campaigns in sexual health; implementation of a research project to investigate young people’s access to health services related to bloodborne viral and sexually transmissible infections, and; support and development of Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers as key front-line clinical health personnel in this area.3

Another outcome of the partnership has been the development of a comprehensive policy response within the NSW HIV, Sexually Transmissible Infections and Hepatitis C Strategies so that Aboriginal people are explicitly recognised as a priority population.

In 2007, the NSW Department of Health released the NSW HIV/AIDS, Sexually Transmissible Infections and Hepatitis C Strategies: Implementation Plan for Aboriginal People. This document described the ways in which both national and state level strategies would be implemented to ensure the full participation of Aboriginal people.2 The Implementation Plan, which covered the period 2006 to 2010, set out the underlying principles of implementing these strategies in Aboriginal communities, starting with community ownership and participation. It then covered the priority focus areas for the strategies, which included workforce development, research and evaluation.2

The Implementation Plan highlights the need for a supported specific workforce to address HIV and community issues associated with stigmatisation, discrimination, low levels of health literacy and low levels of access to primary health-care services. Essential to the Plan and response in NSW are the 40 dedicated Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers placed in Aboriginal community-controlled health services, area health services and non-government organisations (NGOs).3 Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers have a crucial role in the implementation, delivery and evaluation of HIV, sexually transmissible infections and viral hepatitis treatment, care and prevention programs within the Aboriginal community.3 They actively conduct education and prevention programs for Aboriginal families, injecting drug users, inmates, schools, youth and others through workshops, camps, home visits and counselling sessions.3 Furthermore, they play an important role in liaising between various stakeholders such as Aboriginal organisations, non-Aboriginal health services, other health workers, community members and others.3 The Implementation Plan also focuses on the roles and responsibilities of health-service providers. In NSW Aboriginal community-controlled health services provide over 250 000 episodes of care annually to NSW Aboriginal people. The philosophy underpinning this service is one of Aboriginal community control and self determination. These organisations provide culturally-appropriate services based on principles of holistic care and are governed by the local Aboriginal community.18 They play a significant role in the prevention and management of sexually transmissible and bloodborne viral infections, including HIV,3 and many participate in NSW Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers’ projects, through health promotion, community education, and clinical management of HIV infection, as well as social and other welfare needs of people living with HIV.3

|

Responsibility for the implementation of mainstream health services in NSW falls to eight area health services. Recognising the difficulties for some Aboriginal people in accessing Aboriginal community-controlled health services, it is a priority of the area health services that Aboriginal people are able to make full use of mainstream services.3 NSW has the most comprehensive network of sexual health services in Australia, providing care and management for people living with HIV, as well as an extensive Needle and Syringe Program.2,3 Both groups of services play a central role in HIV prevention. Many of the area health services have developed strategies to prioritise Aboriginal people in service delivery and responses3 including the development and implementation of Local and Area Aboriginal Health Partnerships with Aboriginal community-controlled health services and other Aboriginal health services.3,19

Furthermore, both Aboriginal community-controlled health services and the area health services in NSW support and collaborate with NGOs, such as the AIDS Council of NSW, Hepatitis Council of NSW and the NSW Users and AIDS association.1–3,20 These organisations have a special place in reaching out to and providing health promotion and support services to marginalised groups such as gay men, injecting drug users, sex workers and people living with HIV and viral hepatitis, and have dedicated Aboriginal staff to cater to the needs of these populations.3,19–21

Conclusion

While HIV infection rates in the Aboriginal population remain comparable to those in the non-Aboriginal population, there is a window of opportunity to act to prevent further transmission. As was the case twenty years ago, the conditions for a substantial HIV epidemic among Aboriginal people are still present but now there is an improved understanding of where the risks lie. Perhaps the biggest challenge is the number of tailored responses that are required. Continued efforts to prevent transmission among men who have sex with men are as important as improving responses to address the higher rates of infection among heterosexuals and people who inject drugs. These tailored responses must be combined with addressing the ongoing issues related to lower access to health services and more general social and health disadvantage. Aboriginal Sexual Health Workers, in collaboration with Aboriginal community-controlled health services, area health services and NGOs, have come to play a crucial role in reaching out and providing sexual health services to the Aboriginal community. Continued support for these services, including the Aboriginal community-controlled health service workforce, is required to keep HIV at the highest level of Aboriginal health priorities.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5] Fairley C, Bowden F, Gay N, Paterson BA, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN. Sexually transmitted diseases in disadvantaged Australian communities. JAMA 1997; 278(2): 117–8.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | CAS | PubMed | (Cited 9 January 2010.)

[17] Guthrie JA, Dore G, McDonald A, Kaldor J. HIV and AIDS in aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: 1992–1998. The National HIV Surveillance Committee. Med J Aust 2000; 172 266–9.

| PubMed | CAS |

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]