Rural oral health workforce issues in NSW and the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program

John C. Skinner A D , Ward L. Massey B and Mark A. Burton CA Centre for Oral Health Strategy, NSW Department of Health

B Faculty of Dentistry and Health Sciences, Charles Sturt University

C Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University

D Corresponding author. Email: john_skinner@wsahs.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(4) 56-58 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB08065

Published: 27 April 2009

Abstract

Adequate numbers of dental, medical and allied health professionals in rural and regional areas of NSW are vital for the health of these populations and supporting local community structures and economies. Well-documented shortages of health professionals are a major social and political issue in rural and regional communities and this workforce shortfall is recognised by both the NSW Government State Plan and the State Health Plan. This paper outlines rural and regional dental workforce shortages in NSW and describes current rural oral health workforce initiatives, including the new Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program.

Dental workforce shortages in rural and regional areas of Australia and, in particular, New South Wales (NSW), are well documented, most recently by the Parliamentary Inquiry into Dental Services in NSW, which resulted in a number of recommendations directly related to workforce issues.1 These recommendations included new public dental awards, dental award increases, incentives for rural practice and the review of dental education programs. In addition, the NSW State Plan includes a priority to provide ‘Better access to training in rural and regional NSW to support local economies’, while the State Health Plan acknowledges the need to ‘Build regional and other partnerships for health’ and ‘Build a sustainable health workforce’.2,3

NSW dental labour force profile

The NSW Department of Health utilises data from the 2006 Labour Force Survey of dentists and dental auxiliaries registered with the NSW Dental Board to monitor the status of the NSW dental workforce.4,5 The Profile of the Dentist Workforce in NSW, 2006 found that 82% of respondents or 3342 dentists were working in NSW with the majority working in the private sector.4 The average age of dentists was 44.9 years; on average, males were aged 49 years and females were aged 41 years.4

The Profile of the Dental Auxiliaries Workforce in NSW, 2006 found that the majority of dental auxiliaries in NSW were dental therapists working in the public sector and were female with an average age of 45 years.5

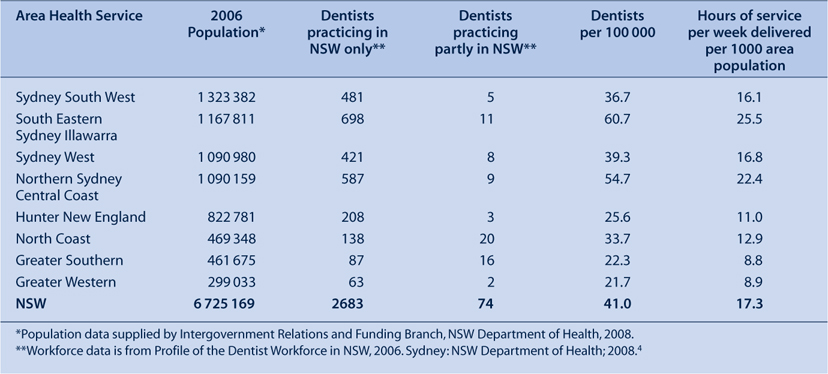

These reports also provide a snapshot of the distribution of the dental workforce in NSW. While it is estimated that there are 45.6 working dentists per 100 000 population in NSW, there are substantial intrastate variations with a high degree of urban concentration (Table 1). Between 1998 and 2006, the proportion of dentists working in rural and regional NSW declined from 14.4% to 12% and the proportion working in inner Sydney rose from 66.7% to 68.2%.4

|

This uneven distribution will be further exacerbated by the shrinking of the dental workforce in both the private and public sectors as professionals reach retirement age. Proportionally, retirement intentions within the next 5 years are greatest among males within rural area health services, particularly the Greater Southern Area Health Service.4 Even though many dentists retire later than most other professionals, the ageing of the profession and growing proportion of female practitioners, who are more likely than males to be in part-time positions, are likely to erode the number of full-time equivalent clinicians and therefore the clinical hours produced.

Attracting professionals west of the Great Divide in NSW is a long-standing issue. Reasons for dental graduates choosing an urban practice over rural practice include: city lifestyle; proximity to family and friends; personal lifestyle preferences; transport issues; and access to professional development.6,7 Conversely, factors influencing the choice of rural employment by health professionals include: a welcoming rural community; ‘partner felt welcome’; family located in a rural area; and outdoor lifestyle.7

Current initiatives aimed at addressing the shortage of dental professionals in rural and regional areas of NSW include: the development of rural dental clinical schools by both the University of Sydney and Charles Sturt University; establishment of Rural Oral Health Centres at key rural and regional locations; rural allowances and scholarships offered by the NSW Department of Health; and rural placements for dentistry students from the University of Sydney. In addition, the NSW International Dental Graduate Program provides up to 12-months of supervised clinical experience for overseas-trained dentists who are enrolled with the Australian Dental Council, but are not yet fully registered in Australia. The 10 dentists who joined the program in January 2009 will be provided with clinical placements in NSW rural area health services wherever possible. The program has been successful in attracting several dentists to rural and regional NSW after their completion of the Program.

The Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program

A longer-term solution has been offered by the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program, which commences in 2009. The Program aims to attract larger numbers of rural students to study and practice dentistry and oral health therapy in rural and regional areas of NSW. With campuses and facilities in Bathurst, Orange, Dubbo, Wagga Wagga and Albury (Figure 1), it is anticipated that the Program will have a positive impact on the number of both private and public dental practitioners entering the profession in rural and regional NSW.

|

Charles Sturt University has demonstrated a substantial level of rural recruitment and retention of graduates from its Faculty of Health Studies who originated from metropolitan areas. Approximately 30% of these metropolitan-sourced but rurally trained health professionals have been shown to remain in country NSW to practice after graduation.5

The first cohort of Charles Sturt University dentistry and oral health graduates will enter the workforce in 2014 and it is expected that up to 60% of these graduates will remain outside of metropolitan NSW (unpublished data; Western Research Institute. Destination of On-Campus Graduates of the Charles Sturt University: 2006 Update). In addition, agreements and partnerships between local area health services and Charles Sturt and other universities are also likely to improve access to public dental services in rural and regional NSW. For example, the Greater Western Area Health Service will share a clinical facility at Dubbo with both Charles Sturt University and the University of Sydney.

Outcomes of the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program will be evaluated, along with the implementation of Rural Oral Health Centres and rural clinical placements by all universities within NSW as part of a review of the NSW Oral Health Implementation Plan 2005–2010.8 In addition, the NSW Government is currently preparing a response to the recently released paper from the National Health Workforce Taskforce on the capacity for health education and training clinical placements across Australia.9

Dental workforce projections

The Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health (ARCPOH) at the University of Adelaide has described data whereby a national average of 49.4 dentists per 100 000 population is a baseline for a projected increase of 29% (to 63.2 dentists per 100 000 population) in 2020.10

Charles Sturt University has campuses within both the Greater Southern and Greater Western Area Health Services (see Figure 1). In 2006, dentist workforce data for these areas varied from 33 to 37 dentists per 100 000 population at area health service level and, on a community scale, varied from 14 to 37 dentists per 100 000 population, both of which are below the suggested national average of 49.4.4

The NSW data show that the regional distribution of dental therapists and hygienists, and the level of service provided are very different to that found in metropolitan areas.4,5 Therapists provide just under twice the number of hours of service per head of population in rural area health services than in metropolitan areas. Hygienists also provide fewer hours of service per head of population in rural areas than their city counterparts.3 With the advent of graduates emanating from regional universities in NSW, Queensland and Victoria, there are likely to be considerable changes to the distribution of these oral health practitioners in the communities that they serve, with little impact on metropolitan workforce projections.

The importance of the availability of dental professionals to rural communities and economies has also been demonstrated by the number of local councils in rural and regional NSW establishing council funded dental clinics. These councils include Gilgandra, Oberon, Narromine, Coonamble, Nyngan and Cobar. In some cases, these services are provided by fly-in or drive-in dentists from Sydney. Modelling by the Western Research Institute has estimated that the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program will generate $52.6 million in gross regional product and $12.3 million per annum in the operational phase (unpublished data; Western Research Institute. Charles Sturt University School of Dentistry and Oral Health Economic Impact Report, 2007). Other likely flow-on effects include the economic impacts of vacant private practices being filled by new graduates from Charles Sturt and other universities.

Conclusion

National dental workforce projections suggest a modest increase in the number of dental professionals nationally by 2020. The distribution of future new graduates is difficult to predict and further concentration in urban areas of NSW is likely to adversely affect rural and regional NSW, where numbers of dental professionals are already low and average ages and retirement rates are highest. The advent of the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program along with other statewide initiatives from NSW Health, other universities and the Australian Government will help address these issues, while also boosting the capacity of both the private and public dental sector. This is more than likely to have positive impacts both socially and economically on rural communities, while also providing an additional career path for local students that does not involve rural–urban migration for tertiary study.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6] Silva M, Phung W, Wong H, Lu J, Aijaz A, Hopcraft M. Factors influencing recent dental graduates’ location and sector of employment in Victoria. Aust Dent J 2008; 51(1): 46–51.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | (Cited 3 March 2009.)

[9]

[10] , Chrisopoulos S, Teusner DN. Dentist labour force projections 2005 to 2020: the impact of new regional dental schools. Aust Dent J 2008; 53(3): 292–6.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed |