Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, November and December 2011

Communicable Diseases BranchNSW Ministry of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(2) 38-42 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12064

Published: 28 March 2012

| For updated information, including data and information on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Public Health and then Infectious Diseases. The communicable diseases site is available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp. |

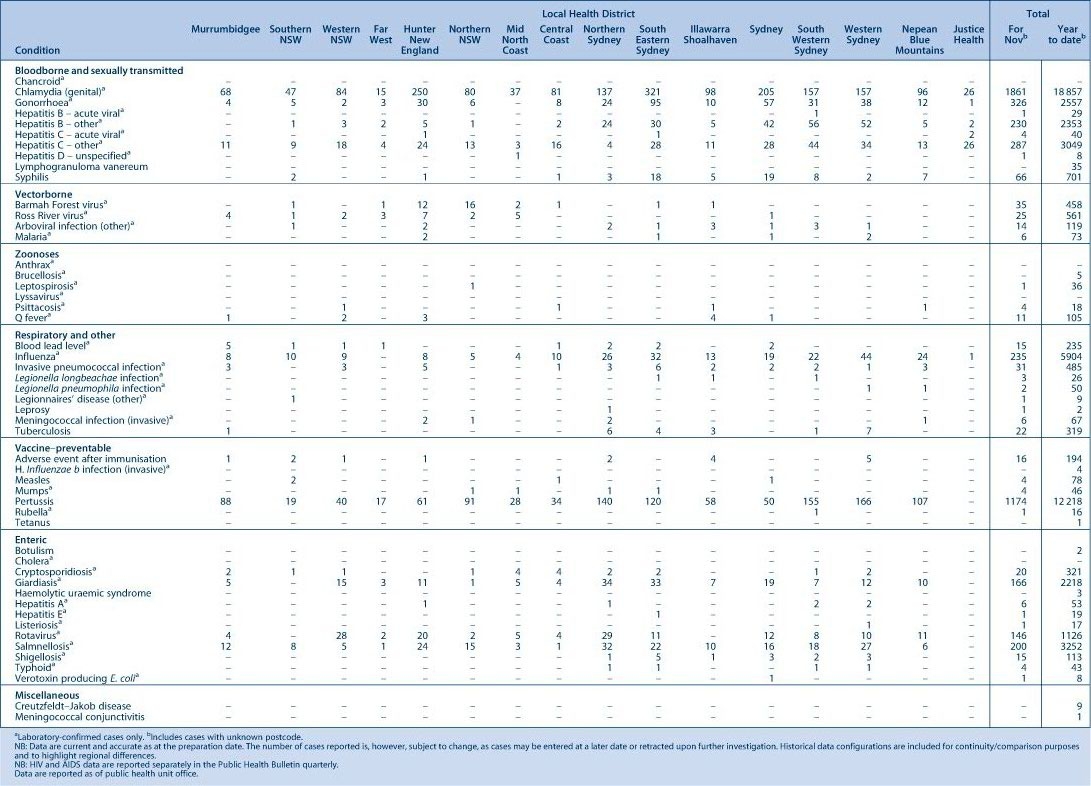

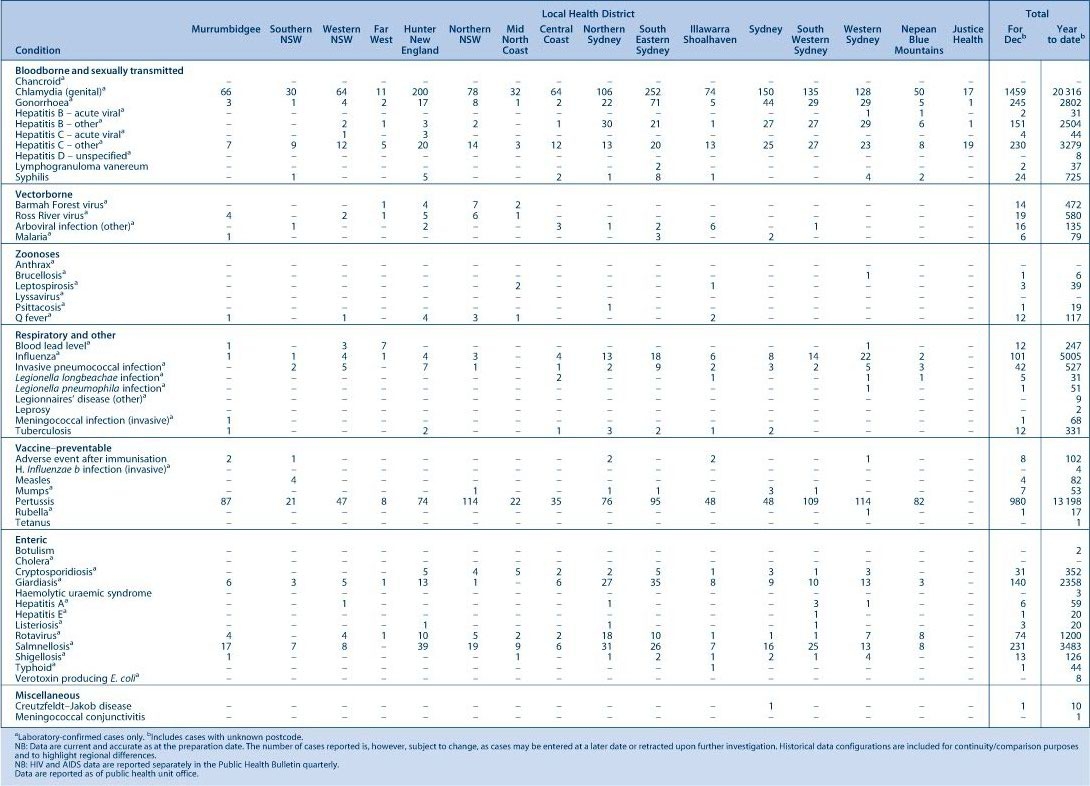

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show notifications of communicable diseases received in November and December 2011 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

Enteric infections

Outbreaks of suspected foodborne disease

Six outbreaks of gastrointestinal disease thought to be due to consumption of contaminated food were reported in November and December 2011. These outbreaks occurred in restaurants or cafes (5) and in a private residence (1); 63 people were affected. Four outbreaks were identified through complaints to the NSW Food Authority (NSWFA) and two outbreaks were identified through emergency department reports to public health units. Stool samples were tested in two outbreaks, and the pathogens identified were Salmonella Typhimurium, and Campylobacter. Due to limited ability to recall the food eaten (in two outbreaks) or lack of an association between eating a particular food and gastrointestinal illness in cases who were interviewed and controls (in three outbreaks), there was not enough evidence to identify the food vehicle in five of the outbreaks.

Scombroid poisoning

In the outbreak where the food vehicle of the illness could be identified, the cause was likely to be fresh tuna steaks used in a salad. This outbreak was identified by emergency department reports to a public health unit in November of symptoms consistent with Scombroid poisoning (skin flushing, headache, tremor, palpitations, tachycardia, hypertension, diarrhoea). Four cases were reported and were colleagues who all reported eating a fresh tuna salad from an organic café. Onset of symptoms ranged from 20 minutes to a few hours after eating the salad. The NSW Food Authority spoke to the café owner who took the salad off the menu. The NSW Food Authority inspected the premises and sampled the small amount of remaining tuna; histamine was detected within acceptable levels. As most of the salad had been sold and only four people had reported illness, the Authority concluded that only a small portion of the tuna product used for the salad that day was contaminated. Food appeared to be maintained at appropriate temperatures. The product was imported from Indonesia by a company in Queensland.

Outbreaks of gastroenteritis in institutional settings

In November and December 2011, 43 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in institutions were reported, affecting 622 people. Twenty-four outbreaks occurred in aged-care facilities, 10 in child-care centres and 9 in hospitals. All outbreaks appear to have been caused by person-to-person spread of a viral illness. In 26 (60%) outbreaks one or more stool specimens were collected. In nine (35%) of these, norovirus was detected. Rotavirus was detected in four (15%) outbreaks. Adenovirus was detected in two (8%) outbreaks. Clostridium difficile was detected in one outbreak along with norovirus; this finding was thought to be coincidental during a viral gastroenteritis outbreak. In six outbreaks no pathogens were detected in stool specimens. Results for five outbreaks are still outstanding.

Viral gastroenteritis increases in winter months. Public health units encourage institutions to submit stool specimens from cases for testing during an outbreak to help determine the cause of the outbreak (for further information see: Guidelines for the public health management of gastroenteritis outbreaks due to norovirus or suspected viral agents in Australia available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-cdna-norovirus.htm-l).

Respiratory infections

Influenza

Influenza activity in NSW was low during November and December 2011. Activity was measured by the number of people who presented with influenza-like illness to 56 of the state’s largest emergency departments, and the number of patients whose respiratory specimen tested positive for influenza at diagnostic laboratories. The rate of laboratory confirmed influenza activity has been declining steadily since activity peaked in mid July 2011.

There were 72 presentations of influenza-like illness (rate 0.5 per 1000 presentations) for November, and 79 presentations (rate 0.5 per 1000 presentations) for December to select Emergency Departments.

There were 176 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza reported in November; including 159 (90%) influenza A and 15 (9%) influenza B. There were 97 cases, including 77 (79%) influenza A and 14 (14%) influenza B, reported in December.

For a more detailed report on respiratory activity in NSW see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/Infectious/influenza_reports.asp.

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Meningococcal disease

Seven cases of meningococcal disease were notified in November and December 2011. Of these, five cases were due to serogroup B and one to serogroup C, while the serogroup was unknown for one case. The case with serogroup C disease was an unimmunised elderly woman who was not eligible for vaccination. There were no deaths due to meningococcal disease reported during November and December.

It is recommended that a single dose of vaccine for meningococcal disease be given to all children at the age of 12 months as well as to those at high risk of disease.1

Measles

All 10 measles cases reported during November and December were linked to cases imported from overseas, with two distinct clusters identified. Seven cases with onset dates during this period were associated with an outbreak at a school in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), of which six were students and one was a health-care worker from a practice where a patient who was a case had presented. The index case was a traveller returning from New Zealand. This cluster highlights the importance of ensuring that all health-care workers have immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases. Documented evidence of two doses of measles, mumps and rubella vaccination or serological evidence of protection from measles is recommended for health-care workers born after 1966. This experience illustrates the challenge to measles control in pockets of non-immunised school children.

For the remaining three cases, an interstate traveller from New Zealand was identified as the likely source of infection for the two other cases: one case was exposed in Sydney, while the other was likely exposed in Victoria and later developed the infection. Both cases were unvaccinated.

Recently, a fatal case of measles was reported in France with acute respiratory distress syndrome, but without rash, emphasising the potentially deadly nature of the disease. This situation highlights the need for health-care workers to consider a diagnosis of measles, even in the absence of classical clinical features, during measles outbreaks.2

Pertussis (whooping cough)

Of the 13 198 pertussis cases reported in NSW in 2011, 2154 cases were reported during November and December. This is considerably lower than the number of cases reported for the same period in 2010 (3491 cases), and lower than the number of cases from September and October 2011 (2408 cases). Caution should be exercised when interpreting these data because of possible delays in notifications.

Immunisation of babies is an important strategy to provide protection for an age group most at risk of severe illness. A free vaccine for infants administered at 2, 4 and 6 months of age is available. It is currently recommended that the first dose can be provided as early as 6 weeks of age and the booster at 3½ to 4 years. In addition, NSW has adopted a strategy to provide immunisation to all other people who care for or who have a baby in the household to encourage them to be fully up-to-date with immunisation. The impact of this strategy is currently being evaluated to inform future vaccine policies.

References

[1] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2008.[2] Lupo J, Bernard S, Wintenberger C, Baccard M, Vabret A, Antona D et al. Fatal measles without rash in immunocompetent adult, France [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis 2012 Mar. Available at: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/pdfs/11-1300-ahead_of_print.pdf[Cited 1 February 2012].