Eye health services for Aboriginal people in the western region of NSW, 2010

Louise Maher A B F , Anthony M. Brown C , Siranda Torvaldsen B , Angela J. Dawson D , Jillian A. Patterson E and Glenda Lawrence BA NSW Public Health Officer Training Program, NSW Ministry of Health

B School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales

C School of Rural Health (Dubbo), The University of Sydney

D Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, University of Technology

E NSW Ministry of Health

F Corresponding author. Email: lmahe@doh.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(4) 81-86 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB11050

Published: 13 June 2012

Abstract

Aim: To assess the availability, accessibility and uptake of eye health services for Aboriginal people in western NSW in 2010. Methods: The use of document review, observational visits, key stakeholder consultation and service data reviews, including number of cataract operations performed, to determine regional service availability and use. Results: Aboriginal people in western NSW have a lower uptake of tertiary eye health services, with cataract surgery rates of 1750 per million for Aboriginal people and 9702 per million for non-Aboriginal people. Public ophthalmology clinics increase access to tertiary services for Aboriginal people. Conclusion: Eye health services are not equally available and accessible for Aboriginal people in western NSW. Increasing the availability of culturally competent public ophthalmology clinics may increase access to tertiary ophthalmology services for Aboriginal people. The report of the review was published online, and outlines a list of recommendations.

Aboriginal people experience a higher burden of eye disease than the general population in Australia. The National Indigenous Eye Health Survey found the rates of blindness in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to be 1.9% which is 6.2 times the rate for non-Aboriginal Australian adults, and low vision prevalence to be 9.4%, 2.8 times the rate for non-Aboriginal Australian adults.1 The major causes of blindness in Aboriginal people are cataract, optic atrophy, refractive error, diabetes and trachoma.1 Although 94% of vision loss in Aboriginal people is preventable or treatable, 35% of Aboriginal adults have never had an eye examination.1

Eye health services at the primary health-care level involve health promotion, screening, treatment of minor problems and referral to eye health professionals. Secondary eye health services are delivered by optometrists and ophthalmologists and include diagnosis and treatment of major eye problems, excluding surgery. Tertiary eye health services are delivered by ophthalmologists and involve surgical interventions in the hospital setting.

The western region of New South Wales (NSW) comprises two Local Health Districts, Western NSW and Far West, and has the highest proportion of Aboriginal residents in the state (8.9%; 26 797 people).2 Aboriginal people in the region are significantly disadvantaged over a range of social and economic indicators including unemployment, household income and educational attainment.3

NSW Health commissioned a review of eye health services for Aboriginal people in western NSW in 2010.4 The aims of the review were to describe and map existing eye health services, to estimate the accessibility of eye health services for Aboriginal people and to make recommendations for improving access to services. This paper describes the findings of this review.

Methods

A mixed methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative data, was used to capture regional service utilisation data, as well as the perspectives and experiences of key service providers.

Data collection

Relevant peer-reviewed and grey literature was analysed to determine the epidemiology of eye health, national and state frameworks for eye health service issues and information related to eye health service providers. Non participant observation was undertaken in six eye clinics. Forty-three key eye health service providers, including program coordinators, optometrists, ophthalmologists and health services managers, were interviewed using standard questions and asked to provide information on services provided.

Cataract surgery rates were used as an indicator of access and uptake of eye health services, as people who have received cataract surgery must have successfully navigated the eye health-care pathway at the primary, secondary and tertiary level. The number of cataract operations received by residents of western NSW for the period July 2007–June 2010 was identified from the NSW Health Admitted Patient Data Collection. The Australian Classification of Health Interventions (7th edition) procedure code blocks 195–200 were used to identify a cataract procedure. Cataract surgery data were disaggregated for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and also for each Local Health District.

Data analysis

Cataract surgery rates (the number of cataract operations per million population per year) were calculated for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the region, using population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics residential population estimates for each year.2 Crude cataract surgery rates are reported, as these rates are the routine method for measuring and reporting cataract surgery coverage in the published literature.5 The number of additional cataract surgeries required for Aboriginal people each year in order for the cataract surgery rates for Aboriginal people to equal the cataract surgery rates for non-Aboriginal people within each Local Health District was also calculated.

Cataract surgery rates were also calculated for three sub-populations in the region: the five local government areas where public ophthalmology clinics are available; the seven local government areas where private ophthalmology clinics are available; and the ten local government areas where no ophthalmology clinics are available. The difference of proportions for cataract surgery rates for these three sub-populations was calculated with a chi-square test using SAS statistical software.

The information retrieved through the document review was synthesised and a thematic analysis was undertaken of the service provider interviews and observations collected during the clinic visits. These were examined according to predetermined themes concerning service availability, accessibility, coordination and uptake in the region.

As a routine review of services within NSW Health, using existing and non-identifiable data, this project did not require review by a Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Availability and mapping of eye health services

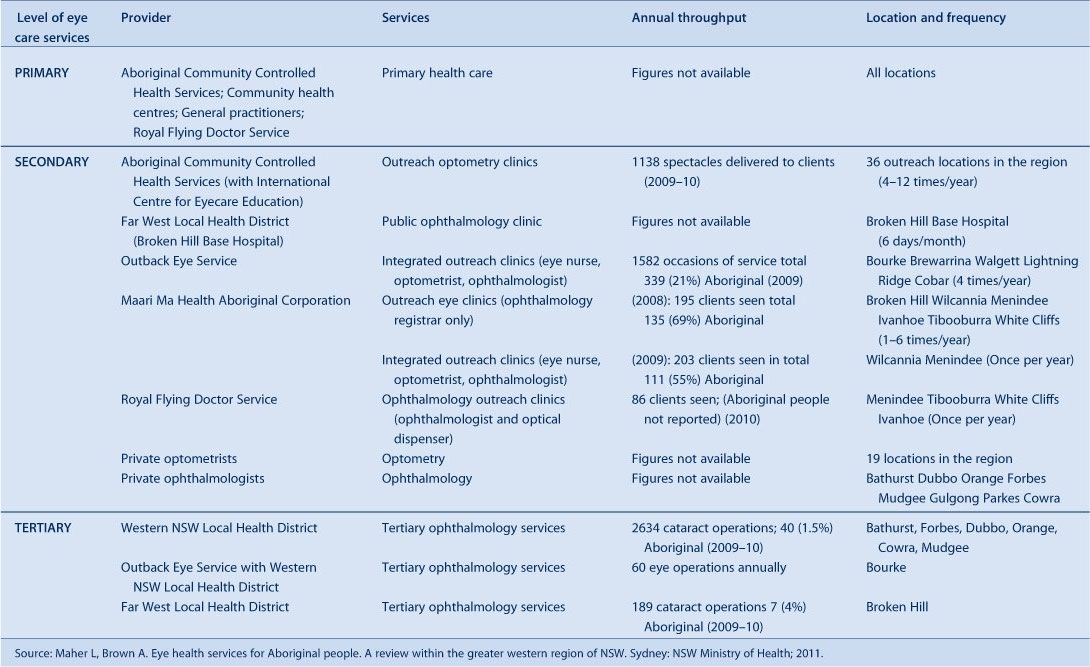

An overview of the services, locations and throughput for these service providers is outlined in Table 1.

|

Outreach eye clinics: The Outback Eye Service conducts integrated outreach eye services in seven locations in the region, delivering public eye clinics with optometry and ophthalmology. The Service also conducts eye surgery in Bourke four times a year, with case coordination and local post-operative follow-up.

Optometry: Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS), together with the International Centre for Eye Care Education, provide outreach optometry clinics in 36 locations across the region, held in local Aboriginal facilities. Regional Eye Health Coordinators based in the ACCHS in Wellington and Walgett manage these clinics and provide case coordination, with optometrists sourced from the region and coordinated by the International Centre for Eye Care Education. Optometry in private clinics is also available across the region, where services are predominantly bulk billed under Medicare, and glasses can be accessed for free through the NSW Government Spectacle Program.

Ophthalmology: Ophthalmology clinics are run by the Outback Eye Service as described above. Broken Hill Base Hospital provides a regular public ophthalmology clinic. The Royal Flying Doctor Service conducts an annual ophthalmology outreach clinic in four locations. Ophthalmologists run private clinics in eight locations in the region, all in larger towns in the south east, and some will bulk bill clients on request. The availability of ophthalmology services is shown in Figure 1. Some areas with large numbers of Aboriginal people have no ophthalmology clinics available, or only private clinics where clients would mostly incur an up-front cost for the service.

|

Surgery: Public ophthalmology surgery is available at seven hospitals in the region.

Access to services

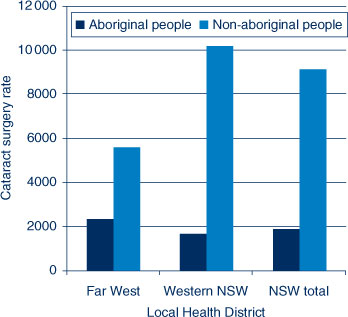

There are limited data available on the use of eye health services for Aboriginal people at the primary and secondary level. At the tertiary level, the cataract surgery rate in western NSW for 2007–2010 was 1750 per million population for Aboriginal people and 9702 per million population for non-Aboriginal people. The cataract surgery rate for Aboriginal people in the Far West Local Health District was 2338 per million population, and 1673 per million population in the Western NSW Local Health District (Figure 2).

|

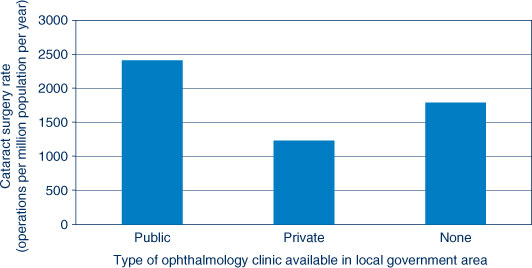

For 2007–2010, an average of 39 Aboriginal people received cataract surgery annually in the Western NSW Local Health District. An additional 197 cataract operations for Aboriginal people would have been required annually on average in this period for the Aboriginal cataract surgery rate to equal the non-Aboriginal rate. In the Far West Local Health District seven Aboriginal people received cataract surgery annually on average for the 2007–2010 period, and an additional 10 surgeries would have been required each year to close the gap in cataract surgery rates. For Aboriginal residents of western NSW, there is a relationship between the availability of a public ophthalmology clinic in their local government area of residence and the rate of access to cataract surgery (Figure 3). There is a significant difference in the cataract surgery rate for Aboriginal people from local government areas with public ophthalmology clinics, compared to local government areas with no clinics or private ophthalmology clinics (χ² test, p < 0.001).

|

Coordination of services

The key stakeholders interviewed reported that there is limited coordination between the key service providers in the region. In some locations there is strong cooperation between primary, secondary and tertiary providers to coordinate eye care services and the patient journey, however in other locations primary providers are unable to facilitate access to secondary and tertiary services. There is no regional coordination of eye health services, or a structure which facilitates collaboration between service providers. The Local Health Districts have no comprehensive eye health-service delivery plans in place.

Monitoring and evaluation of services

Key eye health-service providers monitor their services using different monitoring and evaluation tools and varied reporting strategies. The data available cannot be combined to give an accurate picture of primary and secondary eye health services across the region, due to variations in indicators and data collection systems, as demonstrated in Table 1. There are no systems in place to monitor and evaluate eye health-services delivery for primary or secondary level services across the region. Tertiary level data are available from the Local Health Districts and are routinely monitored to ensure waiting-list benchmarks for surgery are being met, but these data are not analysed to ensure services are equitable.

Targeting services for Aboriginal people

A culturally competent health-care system acknowledges and incorporates the importance of culture, and adapts services to meet culturally unique needs.6 Of the services described, only those delivered by, or in partnership with, ACCHS are specifically tailored for Aboriginal people. The majority of eye health services available are mainstream services. The Outback Eye Service works in close partnership with the ACCHS and the Regional Eye Health Service Coordinators to improve access to the service for Aboriginal people, and 26% of their services are delivered to Aboriginal people. No other services specifically modify their services to improve cultural competence for Aboriginal people. Many key service providers identified lack of cultural competency, particularly in private secondary eye health-service providers, as a significant barrier to accessibility of services for Aboriginal people.

Discussion

This review provides an overview of eye health services in western NSW for Aboriginal people. The focus was on secondary and tertiary services, and service delivery at the primary health-care level was not considered in depth. The review was also limited by the quality and availability of routinely collected service delivery data.

There is differential access to secondary and tertiary eye health services between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in western NSW. There appears to be three main barriers for Aboriginal people accessing secondary eye health services in the region: availability, affordability and cultural competency. In many areas in the region that have a high number of Aboriginal people, there are either no ophthalmology services available, or only private clinics. This review demonstrated a clear relationship between the availability of public ophthalmology clinics and the uptake of cataract surgery for Aboriginal people. The availability of private ophthalmology clinics in an area does not increase uptake of cataract surgery, perhaps because private clinics present cultural and financial barriers for Aboriginal people. The National Indigenous Eye Health Survey identified some of the barriers reported by Aboriginal people that limited access to eye care when there was an eye problem, with the main reasons related to cost, availability and accessibility of services, perceptions around the severity of problems, and people having other priorities.7 These reported barriers are consistent with the findings of this review.

The review identified two other key issues affecting eye health-service delivery, which are limited coordination between the main eye health service providers and incomplete monitoring and evaluation of eye health services in the region. Improved coordination and collaboration between the eye health-service providers in the region could result in improved access to services and eye health for Aboriginal people. Coordinated and integrated eye health clinics improve efficiency of services for patients,8 and one proposed solution involved the establishment of private-public partnerships between the Local Health District, private ophthalmologists, ACCHS, and the Outback Eye Service, whereby outreach eye clinics for Aboriginal people could be established in the private rooms of ophthalmologists. This is a potentially inexpensive initiative that could significantly improve access to and uptake of services for Aboriginal people at the secondary level. Additionally, improved monitoring and evaluation of services will allow information about service delivery and eye health outcomes to be available, and highlight the current inequitable access and uptake of services for Aboriginal people.

The report prepared for the Ministry of Health4 following this review process made a number of recommendations which are consistent with the recommendations in the road map for closing the gap in eye health for Aboriginal people developed by Taylor.9 These recommendations were: to enhance primary eye care as part of primary health care; to increase the availability and accessibility of secondary eye health services in the region; to maintain the availability of tertiary services; to improve coordination of eye care services between key providers; to improve cultural competence of eye health services; and to ensure appropriate monitoring and evaluation of eye health services for Aboriginal people in the region.

Conclusions

Improved availability of affordable and culturally competent services, improved coordination between service providers, and improved monitoring and evaluation of eye health services are recommended to close the gap in eye health for Aboriginal people in western NSW.

Acknowledgment

This work was completed while LM was an employee of the NSW Public Health Officer Training Program, funded by the NSW Ministry of Health. The Program is offered in partnership with the University of New South Wales. She undertook this work while based at the School of Rural Health (Dubbo) of The University of Sydney.

References

[1] Taylor HR. The prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous Australians: the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Med J Aust 2010; 192 312–8.[2] Centre for Epidemiology and Research. ABS Population Estimates (HOIST). Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2011.

[3] NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs. Two Ways Together Regional Report. Public report. Murdi Paaki. November 2006. Sydney: NSW Department of Aboriginal Affair; 2006. Available at: http://www.mpra.com.au/Regional%20Reports/061116%20MurdiPaaki%20Public%20TWTRegionalReport.pdf (Cited 20 November 2011).

[4] Maher L, Brown A. Eye health services for Aboriginal people. A review within the greater western region of NSW. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2011.

[5] World Health Organization. Vision 2020 The right to sight. Global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. Action Plan 2006–2011. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

[6] Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O, . Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep 2003; 118 293–302.

[7] Taylor HR, Stanford E. Provision of Indigenous Eye Health Services. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, The University of Melbourne; 2010. Available at: http://www.iehu.unimelb.edu.au/about_us/?a=326761 (Cited 20 November 2011).

[8] Turner AW, Mulholland WJ, Taylor HR. Coordination of outreach eye services in remote Australia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2011; 39 344–9.

| Coordination of outreach eye services in remote Australia.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[9] Taylor HR, Boudville A, Anjou M, McNeil R. The roadmap to close the gap for vision. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, The University of Melbourne; 2011.