The Healthy Built Environments Program: a joint initiative of the NSW Department of Health and the University of NSW

Susan M. Thompson A D , Andrew Whitehead B and Anthony G. Capon A CA Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales

B Centre for Health Advancement, NSW Department of Health

C National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, The Australian National University

D Corresponding author. Email: s.thompson@unsw.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 21(6) 134-138 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB10020

Published: 16 July 2010

Abstract

The built environment is increasingly viewed as an important determinant of human health. Consequently creating environments that promote health and wellbeing is one of the NSW Department of Health’s key preventive health priorities. This article describes a new program focused on improving health through the quality of the built environment. Recently established in the City Futures Research Centre, Faculty of the Built Environment, University of NSW, the Healthy Built Environments Program receives funding from the NSW Department of Health. The Program will foster cross-disciplinary research, deliver education and workforce development, and advocate for health as a primary consideration in built environment decision making. The Program brings the combined efforts of researchers, educators, practitioners and policymakers from the built environment and health sectors to the prevention of contemporary health problems. The Program’s vision is that built environments will be planned, designed, developed and managed in ways that promote and protect the health of all people.

In recent years, there has been rising international interest in, and concern about, links between human health, the built environment and ecological sustainability.1–3 There is increasing evidence that the physical form of our cities affects health.1–7 Neighbourhoods where it is easy to cycle or walk from home to shops and places of employment have been shown to positively contribute to human and environmental health.4–7 Conversely, localities that are more spread out, with segregated land uses, disconnected street patterns and limited public transport, are associated with car dependency, less physically active lifestyles of their residents and greater social isolation.4–7 These urban forms also contribute to climate change with excessive greenhouse gas emissions created by dependency on cars.

Urban planning has a long association with health. The discipline originated out of concern for human health8 and as far back as a century ago was strongly aligned with public health objectives to prevent the spread of disease. Nevertheless, this close relationship between health and urban planning was not sustained as planning moved to focus on urban policy development, design and environmental sustainability, while public health largely pursued a medical model.9 Today however, there is a gradual re-alignment of the two as understanding grows of the role that the built environment plays in supporting human health. This paper introduces a recent New South Wales (NSW)-based initiative – the Healthy Built Environments Program (HBEP). Arising from health concerns, the Program is uniquely situated within an urban planning and design context, and will have a strong environmental sustainability focus.

How did we get here?

At the international level, recognition of the need to embrace a broader understanding of health goes back to the 1970s when the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned the development of a program of public health reform which today is known as Health21.3,10 In 1986 this led to the declaration of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion and the establishment of the WHO Healthy Cities Project. In 1992 the United Nation’s Agenda21 emerged from its Earth Summit Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, linking environmental sustainability and human health.3 Both Health21 and Agenda21 today underpin the WHO Healthy Cities Project, which links health and sustainable development at the local level.3 Healthy Cities Projects in Australia include Onkaparinga (formerly Noarlunga) in South Australia10 and the Illawarra in NSW.11

In Australia, the health sector has led policy initiatives to bridge health and the built environment. Most recently, the Australian Government undertook national reviews of health promotion and the health system more generally.12,13 The views of urban planners and designers have informed key recommendations emerging from these reviews. Multiple perspectives have been encouraged in other forums. For example, the Australian Academy of Science 2006 Fenner Conference, Urbanism, Environment and Health, brought together researchers, policymakers, industry and community across a range of disciplines and sectors.14 Other significant integrative work includes that of the Victorian Division of the Heart Foundation and its Healthy by Design resource.15 In NSW, the Premier’s Council for Active Living seeks to strengthen the physical and social environments in which communities engage in active living.16 Also in NSW, health impact assessment (HIA) has been identified as a ‘key tool for affecting change and to strengthen health input into planning decisions’.17

The Healthy Built Environments Program

With the built environment increasingly viewed as an important determinant of health, creating environments that promote health and wellbeing is one of the NSW Department of Health’s preventive health priorities. The importance of preventive health has been identified by the NSW Government in its State Plan,18 with further clarification about the role that urban planning plays in relation to human health in the NSW State Health Plan.19 While evidence continues to emerge, the NSW Department of Health is aware that more is needed, in particular, information about the impacts of different patterns of urban development on health and the costs and benefits of these impacts.

Consequently, the Department has established the Healthy Built Environments Program at the City Futures Research Centre in the Faculty of the Built Environment at the University of NSW (http://www.fbe.unsw.edu.au/cf/hbep). This 5-year Program will foster interdisciplinary research, deliver innovative education and workforce development, and provide leadership on health and the built environment.

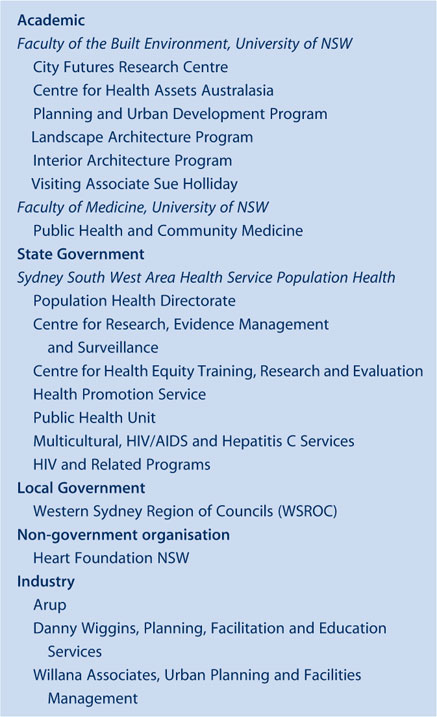

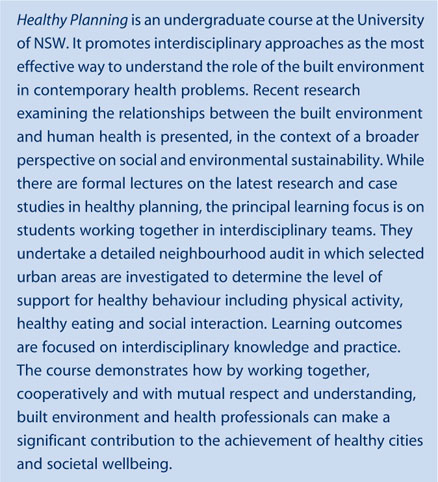

The Program brings together a multidisciplinary team from academic, government, private and non-government organisation (NGO) sectors with expertise across health, urban planning and design, and their inter-relationships (Box 1). The Program is situated in one of Australia’s largest faculties of the built environment, which includes all of the design and planning disciplines across scales from individual buildings (their interiors and what is between them), through neighbourhoods, to the urban region, city and beyond. The backgrounds of the Program’s co-directors Thompson (an urban planner) and Capon (a public health physician) reflect the need for multiple perspectives. Thompson has been leading an undergraduate healthy planning subject since 2007 (Box 2). A new postgraduate course with strong links to the Healthy Built Environments Program has recently been approved by the Faculty’s Education Committee.

|

|

Positioning the Program within a built environment faculty offers the opportunity to influence the built environment professions and industries to incorporate healthy planning provisions in strategic direction, policy formulation and decision making. With an already established research and educational focus on environmental and social sustainability, the opportunities to develop integrated strategies that bring human health concerns into alignment with environmental issues are considerable.

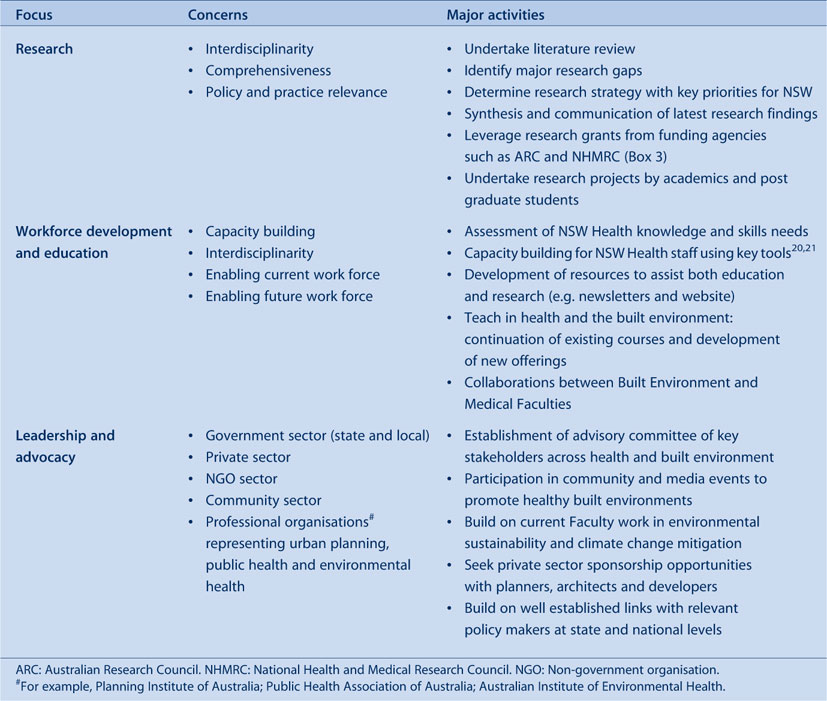

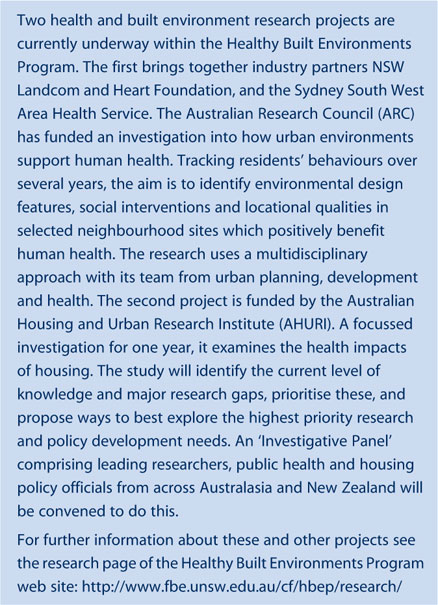

Table 1 presents the principal activities of the Program across its three main themes: research, workforce development and education, and leadership and advocacy. Box 3 provides two examples of research projects in the Program.

|

|

Challenges in moving forward

There are important potential obstacles to progress on healthy built environments. These include different ways of understanding health, and evidence about health, and the need for effective interdisciplinary collaboration.

Epidemiology is the established method for understanding the distribution of health and disease in populations and has enabled the identification of many major risks to health. Epidemiology in its current form is however less useful for understanding the complex interplay between multiple biophysical, social and economic factors and the health of people in urban environments. Consequently, it has been argued that epidemiology needs to adopt and develop methods to understand such complexities by drawing insights from ecology.22 From the planning perspective, Corburn’s ‘relational view of place’, where he argues for combining laboratory and field site views of urban health, is another methodological model that may be useful in formulating different understandings of health.1

A related challenge is to overcome the constraints imposed by disciplinary boundaries and different traditions of evidence. Lawrence23 argues for integrative and interdisciplinary approaches in responding to links between the built environment and health. An effective interdisciplinary approach acknowledges individual disciplinary expertise and brings it together with expertise in other disciplines to create new knowledge. The web-based resource, Healthy Spaces and Places, launched last year, is an example of an effective interdisciplinary initiative (Box 4).

|

Conclusion

Interest in the role that environments play in supporting good health, both physical and mental, is high in many countries. In Australia this heightened interest is reflected at national, state and local government levels. Increasingly urban planners and health professionals are working productively together in both strategic policy development and specific service delivery. In order to make progress in climate change mitigation and human physical and mental health improvements, an important challenge will be to shift the way we understand health in the context of built environment and sustainability discourse. The Healthy Built Environments Program, with its interdisciplinary approach, positioned in a faculty of the built environment and with a focus on environmental and social sustainability, is well placed to meet this challenge.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4] Badland HM, Schofield GM, Garrett N. Travel behaviour and objectively measured urban design variables: associations for adults travelling to work. Health Place 2008; 14(1): 85–95.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Accessed 24 February 2010.)

[12]

[13]

[14] Capon AG, Dixon JM. Creating healthy, just and eco-sensitive cities. N S W Public Health Bull 2007; 18 37–40.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Accessed 24 February 2010.)

[17] Thackway SV, Milat AJ, Develin E. Influencing urban environments for health: NSW Health’s response. N S W Public Health Bull 2007; 18 150–1.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | (Accessed 24 February 2010.)

[21]

[22] March D, Susser E. The eco- in eco-epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35(6): 1379–83.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Accessed 24 February 2010.)