Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, November and December 2008

NSW Department of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(2) 31-35 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB09006

Published: 25 February 2009

Abstract

For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Infectious Diseases or access the site directly at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp.

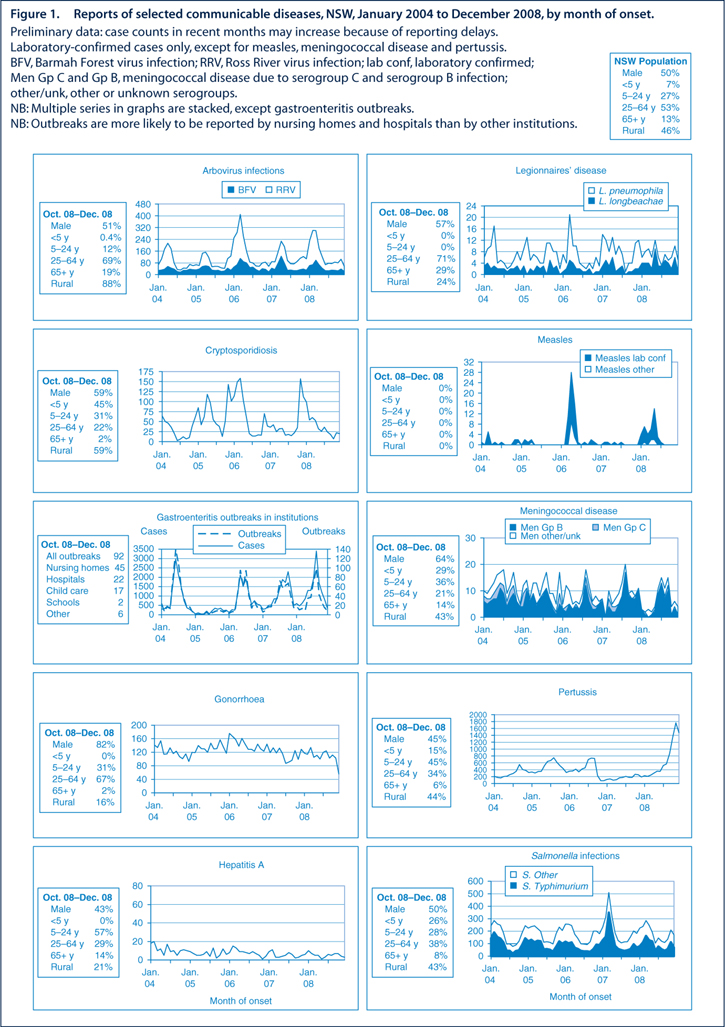

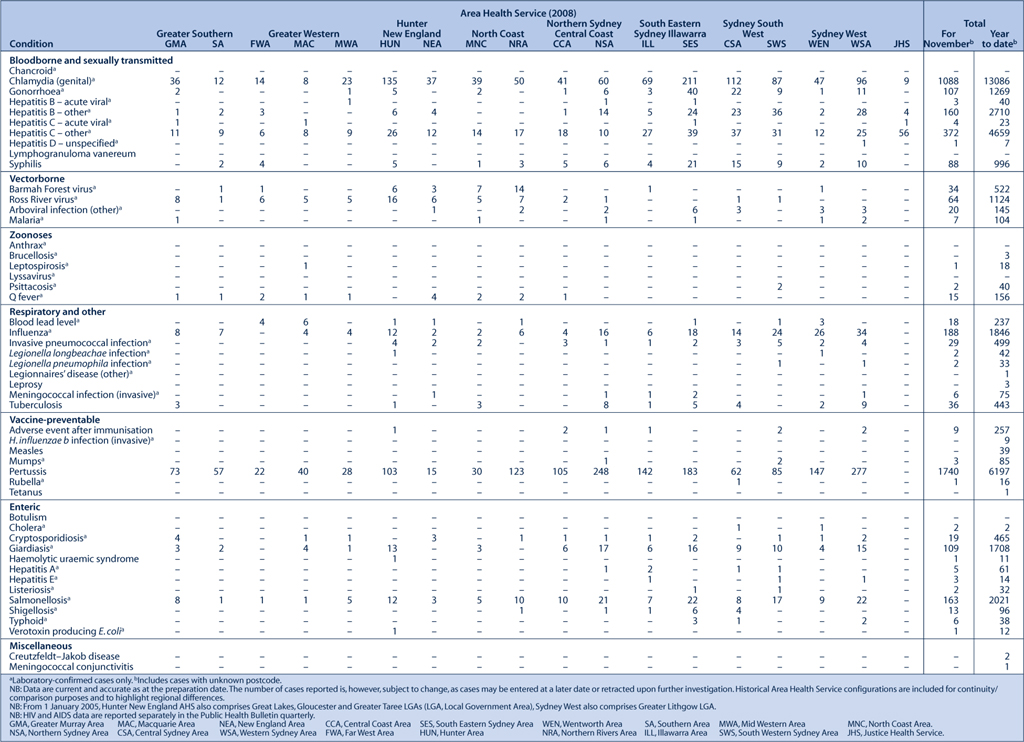

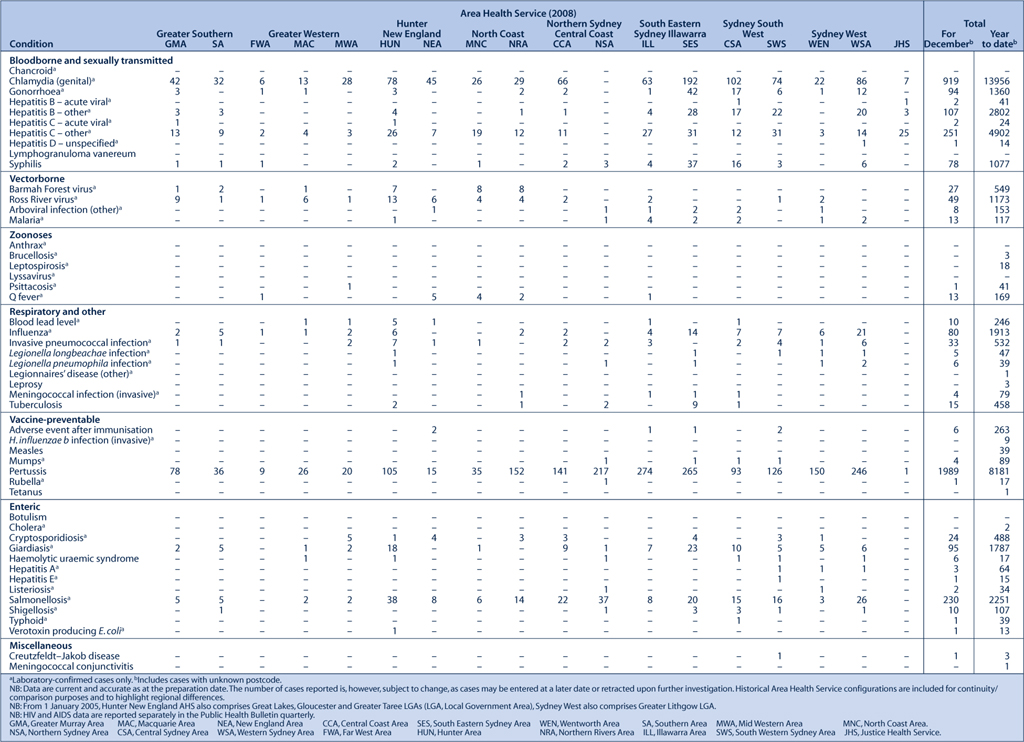

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show reports of communicable diseases received through to the end of December 2008 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

Pertussis (whooping cough)

An outbreak of pertussis that commenced in northern NSW in late 2007 has continued to spread across NSW. In November and December, there were 1740 cases and 1989 cases respectively reported. A total of 8181 cases were reported in 2008, equivalent to 119 cases per 100 000 people. This represents a significant increase since 2007 where 2097 cases were reported (30/100 000 people).

Cases under 1 year of age had the highest age-specific incidence (346 cases notified, which is equivalent to 386 cases per 100 000). Many of these children were not yet immunised as the vaccine is routinely given at 2, 4 and 6 months of age. No deaths were reported in children or infants who are normally at greatest risk of severe morbidity and mortality from pertussis.

A second peak was seen in children aged around 14 years, where there were 293 cases reported (equivalent to an age-specific rate of 318 cases per 100 000). A school-based pertussis booster immunisation program is due to commence in 2009, targeting children in year 10 who will be aged around 15 years.

In recent months, the proportion of cases diagnosed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has increased substantially and the majority of cases are now diagnosed using PCR rather than by serology. This is likely to reflect the increased proportion of cases in younger age groups where PCR-based diagnosis is typical and clinicians have increased awareness of the availability and advantages of PCR tests over traditional serological testing methods.

Key public health messages for pertussis have included recommendations:

-

to ensure that pertussis vaccines are given on time to babies at 2, 4 and 6 months and the booster is given to children at 4 years

-

to inform the community about the adult booster vaccine for parents and carers of babies and young children, child-care workers and health-care workers

-

to be alert for the clinical features of pertussis and seek medical assessment promptly; early diagnosis and treatment reduces the period of infectiousness

-

to administer chemoprophylaxis to contacts where the case is likely to have significant contact with at-risk infants who are at greatest risk of severe disease.

Enteric diseases

In November and December 2008, NSW public health units investigated 61 outbreaks of gastroenteritis, including 47 where person-to-person transmission was likely and 14 suspected to be the result of foodborne transmission.

The 47 suspected person-to-person outbreaks affected a total of 569 people. Twenty-four occurred in aged-care facilities and affected 384 people, 11 occurred in hospitals and affected 109 people, 10 occurred in child-care centres and affected 66 people, and there were two outbreaks in other institutional settings affecting 10 people. Clinical specimens were submitted for testing from 21 of 47 (45%) suspected person-to-person gastroenteritis outbreaks. Norovirus was identified in five outbreaks. The causative agent was not determined or reported for the remaining outbreaks.

Outbreaks suspected to be caused by food were commonly reported in November and December. These 14 outbreaks affected at least 146 people. Two of these outbreaks, where more than 20 people were infected with Salmonella, were associated with cakes containing raw egg mousse from the same bakery. The eggs were traced back to a farm where Salmonella was identified following an environmental investigation by the NSW Food Authority. The same egg farm was linked to a gastroenteritis outbreak earlier in 2008. Another Salmonella outbreak was related to deli meats purchased from a supermarket. Two outbreaks, affecting 20 people, were caused by Clostridium perfringens in curry meals.

The remaining outbreaks were small, affecting three and four people after restaurant meals. No pathogens were detected in any of these cases. The sites of the outbreaks were inspected and no known sources were identified.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are bacteria that can cause serious gastrointestinal disease characterised by diarrhoea, which in some cases can be bloody. In a small proportion of cases, STEC can progress to haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), which results in kidney failure, bleeding and anaemia. Infections tend to increase in the warmer months.1

In November and December 2008, NSW public health units were notified of eight STEC (two serotype O157 and seven of unknown serotype) and six HUS cases (three were also STEC positive). Of the eight cases, ages ranged from 2 to 75 years. Six were female and two male. The HUS cases were in both children and adults over 40. This number of STEC and HUS cases is consistent with the seasonal increase seen at this time each year.

STEC infection can be transmitted through:

-

eating contaminated food (undercooked hamburgers, unwashed salad, fruit, vegetables and unpasteurised milk or milk products)

-

drinking or swimming in contaminated water

-

person-to-person contact; for example, contact when changing a nappy with the faeces of a child with the infection

-

-

The most important ways to prevent infection with STEC and other foodborne diseases are to:

-

-

cook hamburgers and sausages thoroughly to at least 71°C. Although colour alone is not necessarily a good indicator, do not eat hamburgers or sausages if there is any pink meat inside

-

wash hands well after handling raw meat

-

use different knives and cutting boards for raw meat preparation and other food preparation

-

wash raw vegetables and fruits thoroughly

-

refrigerate perishable food until ready to eat – so that bacteria do not incubate out of the fridge

-

wash hands well after touching animals or their faeces.

For more information see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/Infectious/a-z.asp

[1] Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Esceherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 2005; 365 1073–86.

| PubMed |

[2]

[3] Razzaq S. Hemolytic uremic syndrome: an emerging health risk. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74 991–6.