Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, July and August 2008

NSW Department of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 19(10) 186-190 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB08058

Published: 21 November 2008

For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Infectious Diseases or access the site directly at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp.

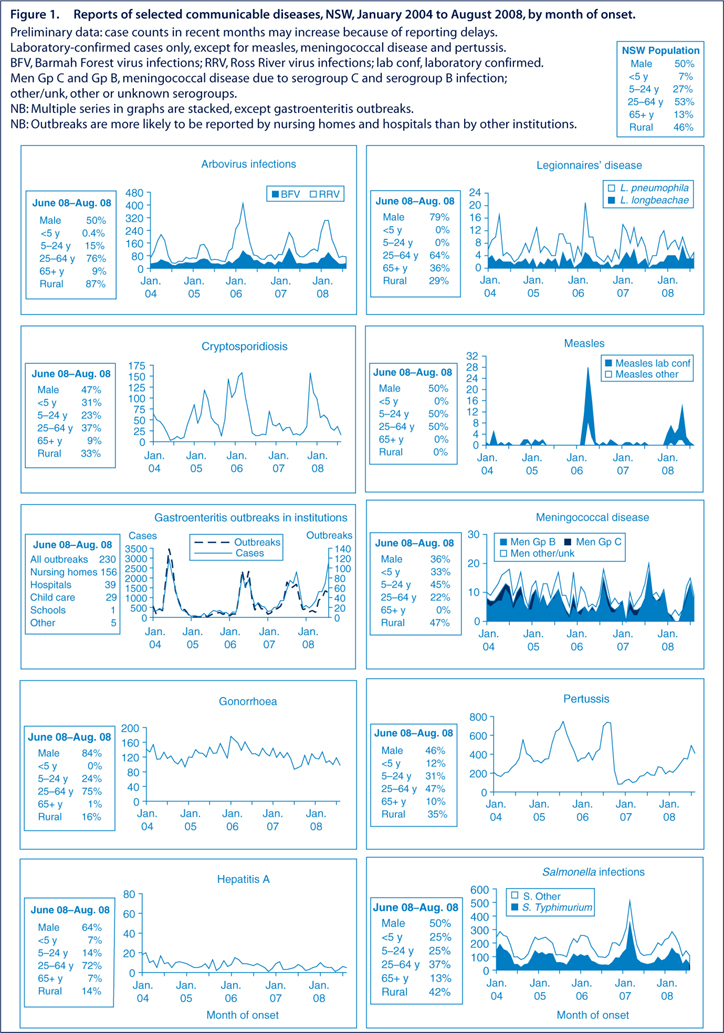

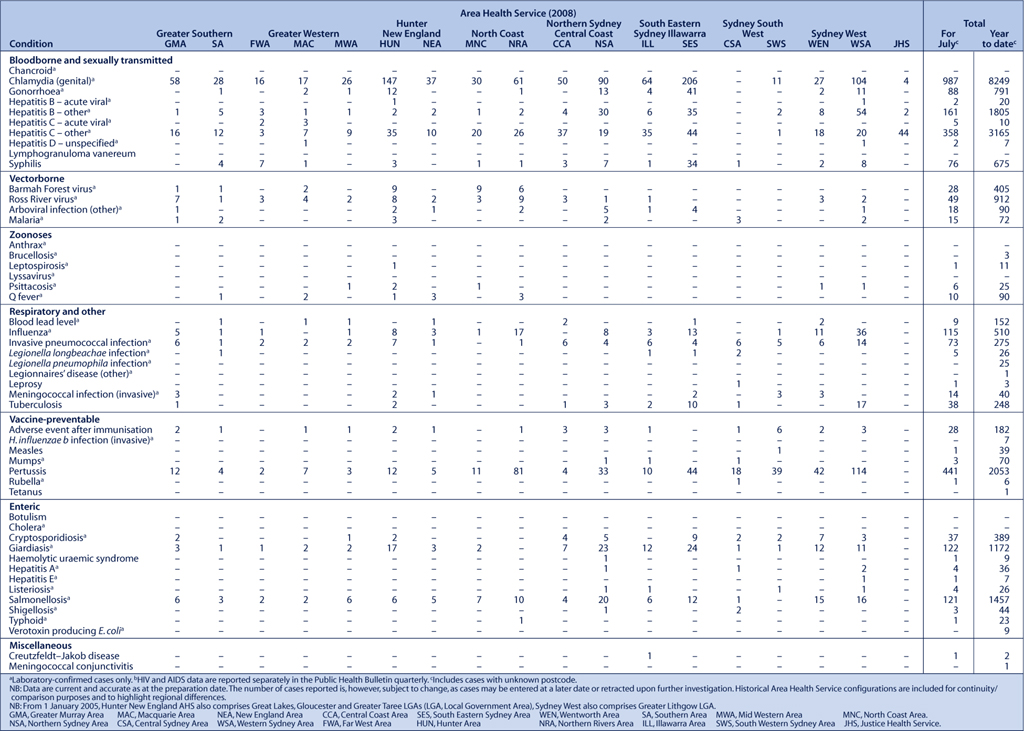

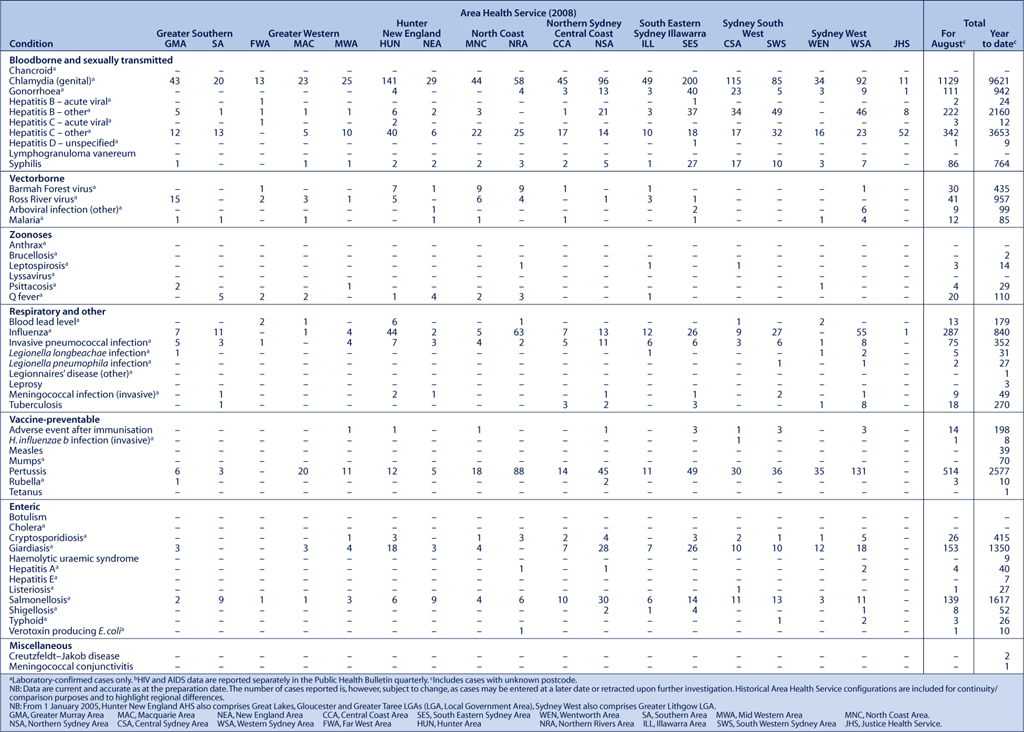

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show reports of communicable diseases received through to the end of August 2008 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

Influenza

The expected seasonal increase in influenza cases was reported in July and August. There were 402 laboratory-confirmed cases notified across the state.

A number of influenza outbreaks were identified among pilgrims attending the Catholic World Youth Day event in July. Because of the mass gathering of people, observed rapid spread and significant morbidity among those infected, public health interventions were recommended to reduce the spread of disease and to minimise hospitalisations. These included sick pilgrims wearing masks and being isolated from others. Advice was provided through group leaders to minimise transmission within groups during the event. Further measures were taken to minimise the risk of spread on transport as the event concluded, with the provision of fact sheets and special hygiene packs for those travelling on buses.

Typical of this time of year, a number of outbreaks also occurred in institutions, including residential aged-care facilities, hostels and boarding schools. Such outbreaks often affect staff as well as residents or students, and highlight the importance of immunisation in at-risk groups and those working with them.

A higher prevalence of circulating influenza type B was observed in NSW this season compared with recent years. A similar pattern was reported in a number of other states.1

Influenza is formally notified to NSW Health when confirmed by a laboratory test; however, notifications represent a small fraction of the amount of illness in the community from this seasonal infection. General trends are monitored with additional data from three further sources:

-

influenza-like illness presentations to 28 emergency departments across NSW

-

deaths due to influenza or pneumonia

-

outbreaks.

Compared with other respiratory viruses, influenza tends to cause more severe complications, such as pneumonia, particularly in elderly people and other vulnerable groups such as small children and those with concurrent illnesses (including heart disease, lung disease or diabetes).

Suspected Hendra virus infection excluded

In early August, a laboratory test result from a sick horse at a training facility in northern NSW led veterinarians to suspect Hendra virus infection. The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) contacted NSW Health to warn of a possible risk to human health. To contain a possible outbreak, the DPI initiated a number of actions, including placing the stable where the potentially infected horse was located under quarantine.

The local public health unit identified 15 people who had been in recent close contact with the ill horse and arranged testing for them. Advice was given to stable staff to avoid contact with the ill horse unless absolutely necessary and to wear personal protective equipment when in contact with the animal. Similar advice was given relating to healthy horses in the same stable that may have been incubating the illness. However, communication of the level of risk was difficult given that there is still limited knowledge regarding the behaviour of the virus.

Seven contacts accepted the offer of testing; all were negative on standard tests. Further testing eventually confirmed that the test result of the original ill horse was a false positive, with no evidence of true Hendra virus infection. The episode, however, highlighted the benefits of a close working relationship between NSW Health and the DPI.

Hendra virus spreads from flying foxes to horses. It causes a variety of symptoms and can be fatal to the horse. On rare occasions the virus has spread from horses to humans. One equine case of Hendra virus infection occurred in NSW in 2007; however, there have been no cases of human Hendra virus infection in the state.2

Within Australia, there have been only six confirmed occasions, all in Queensland, of the virus spreading from horses to humans. Three people who have contracted the illness have died, the first two in 1994 and 1995.3 At the time of this episode, another two people were unwell from Hendra virus, one of whom subsequently died. Three people diagnosed with Hendra virus infection have later recovered. All six cases had been in very close contact with sick or dead horses.3

Symptoms of Hendra virus infection in humans have included:3

-

an influenza-like illness, which can progress to pneumonia

-

encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) with headache, high fever and drowsiness, which can progress to convulsions or coma.

The incubation period in humans has been estimated to be from 5 to 14 days. However, in one of the three fatal cases, encephalitis subsequently occurred 13 months after the initial exposure. The limited data available have not indicated human-to-human transmission.

Enteric diseases

In July and August 2008, NSW public health units investigated 204 outbreaks of gastroenteritis, including 196 suspected to be caused by person-to-person transmission, and eight suspected to be the result of foodborne transmission.

The 196 suspected person-to-person outbreaks affected a total of 3023 people. One hundred and thirty-six occurred in aged-care facilities and affected 2290 people; 31 occurred in hospitals and affected 413 people; 25 occurred in child-care centres and affected 292 people; one outbreak at a school affected eight people; and three outbreaks in other institutional settings affected 20 people.

Clinical specimens were submitted for testing for 92 of the 196 suspected person-to-person outbreaks. Rotavirus was confirmed in stool samples from four outbreaks, norovirus was identified in 44 outbreaks and in one aged-care facility both rotavirus and norovirus were detected. The causative agent was not determined for the remaining 43 outbreaks.

Of the eight suspected foodborne gastroenteritis outbreaks:

-

Two affected 13 people in whom illness was associated with having eaten oysters at separate private functions in the same geographic region. The NSW Food Authority investigated the source oyster farm and detected norovirus in oysters. This lease was closed as a result.

-

Four affected a small number of people after consuming restaurant or takeaway meals. No pathogens were detected in these cases. The premises were inspected but no known sources were identified.

-

One outbreak occurred among work colleagues who attended a lunch. Sandwiches from commercial premises were implicated and contamination from a sick food handler was suspected as the source. Food handlers should not attend work until 48 hours after gastrointestinal symptoms have resolved.

-

One outbreak was identified in July 2008 following an increase in notifications of a rare serovar of Salmonella, S. Anatum. Between 13 May and 2 July, there were nine confirmed cases of S. Anatum infection in two area health services (Sydney South West and Sydney West). The median age of the cases was 26 years; four cases were male. Three of the five cases contactable for interview reported eating a meal from the same restaurant. The NSW Food Authority conducted an environmental investigation at the premises, with food and environmental samples taken. One sample collected from a stainless steel bench in the food preparation area was positive for S. Anatum. One of the food samples was positive for Salmonella but not S. Anatum. The source of contamination of the environment could not be identified. There have been no further cases of S. Anatum linked to this premises.

The NSW Food Authority assisted the public health unit of Sydney West Area Health Service in the investigation of several episodes of diarrhoea-predominant illness in residential facilities in western Sydney in July and August. Clostridium perfringens was the suspected causative agent in each case, although the mechanism of contamination is not yet clear. Further investigation of this issue is underway.

[1]

[2]

[3]