Braiding Indigenous oral histories and habitat mapping to understand urchin barrens in southern New South Wales

Kyah Chewying A B * ,

A B * ,  A B E and Kerrylee Rogers

A B E and Kerrylee Rogers  A B

A B A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

The sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) is linked to urchin barrens and potential kelp forest depletion along New South Wales (NSW) southern coast. Whereas previous studies employed scientific methods to evaluate barrens, Indigenous Traditional Knowledges offer valuable insights into urchin population dynamics.

This study aimed to ‘braid’ Traditional Knowledges with Western science to better understand urchin barrens in the region.

Yarning circles with Walbunja Traditional Owners were conducted alongside habitat mapping using image segmentation of remotely sensed imagery.

Traditional Knowledges highlighted long-term declines in culturally significant species, including snapper (Pagrus auratus), lobster (Jasus edwardsii), groper (Achoerodus viridis), abalone (Haliotis rubra) and cuttlefish (Sepia apama). Habitat mapping showed dynamic vegetation cover, although differentiating kelp from other vegetation posed challenges. Urchin barrens were present across all study sites as part of a habitat mosaic typical of NSW rocky reefs.

This research demonstrated the value of braiding Traditional Knowledges with Western methods to enhance understanding of kelp and urchin dynamics.

The results of the yarning circles suggest that utilising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in future studies would improve ecological insights and inform sustainable marine management strategies. Further, the habitat mapping has highlighted the need for higher resolution aerial imagery.

Keywords: braiding, Centrostephanus rodgersii, habitat extent, kelp gardens, macroalgae, remote sensing, traditional knowledge, yarning circles.

Introduction

Barrens (also called coralline flats) are a distinct habitat devoid of macroalgae and often covered in crustose coralline algae. They have been linked to the proliferation of urchins, including the long spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii), in south-eastern Australia and New Zealand (Balemi and Shears 2023). Within New South Wales (NSW), barren habitats are considered stable (Przeslawski et al. 2023). Further, barrens have been identified as important to the natural underwater landscape in NSW, and have been associated with distinct or diverse fish assemblages and microbes (Curley et al. 2002; Coleman and Kennelly 2019; Kingsford and Byrne 2023). A combination of macroalgae beds, algal turf and urchin barrens (also known as mosaics) are a part of the nature of underwater habitats that make up subtidal rocky reefs in NSW (Underwood et al. 1991). It has been previously indicated that urchins within barren habitats are malnourished with reduced gonads (Pert et al. 2018); however, Centrostephanus rodgersii can exist within barrens and have the same amount of ‘gut fullness’ as it does within in macroalgae-dominated habitats (Day et al. 2024), meaning that urchins hold a sufficient diet both within and outside of barrens in NSW.

Centrostephanus rodgersii is native to south-eastern Australia and New Zealand (Thomas et al. 2021). In NSW, C. rodgersii lives in depths ranging from 7 to 27 m (Worthington and Blount 2003), and in Tasmania in depths from 7 to 57 m (Perkins et al. 2015). The species is nocturnal (Ling et al. 2016), abundant in crevices and depressions on the seafloor, and mostly found in areas free of macroalgae called barrens (Byrne and Andrew 2013). In recent decades the species has extended its range into Tasmania owing to ocean warming (Ling 2008) and its wide larval thermal tolerance (Byrne et al. 2022). Subsequent high abundances in Tasmania have been associated with loss of kelp ecosystems (Mabin et al. 2019) and led to development of programs to cull and reduce density to improve ecosystem resilience (Westcott et al. 2022).

Previous studies have used various methods to understand C. rodgersii and its role in maintaining barrens in NSW, including underwater visual census, underwater imagery, aerial imagery, dissections and manipulative experiments (Przeslawski et al. 2023). All of these represent Western science approaches. The role of C. rodgersii in NSW is not clear, and there is ongoing debate about whether: (i) the species is a natural part of NSW rocky reef mosaics or (ii) population density has recently surged and caused barrens to replace kelp ecosystems (Kingsford and Byrne 2023). Understanding of the population dynamics of C. rodgersii is currently limited by a lack of historical data and difficulties with collecting long-term and comparable data on urchin barrens. Traditional Knowledge of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities may address these limitations by increasing the temporal range of available knowledge to show whether urchin barrens on the south coast of NSW are a natural and stable occurrence.

A key point of conflict regarding urchin barrens is whether the proliferation of urchins is a response to the emergence of an alternative stable state or is influenced by various external affecting factors, such as reduction of predators (possibly by overfishing) and climate change (Ling et al. 2009). Stable states have been defined as non-transitionary states that persist over ecologically relevant timescales and contribute to the development of stable equilibrium states (Stewart and Konar 2012). Within NSW, urchin barrens are considered to be stable in nature, because there has been no significant fluctuation in percentage of barren coverage at a large spatial scale from Newcastle to Eden (Glasby and Gibson 2020). Although kelp and urchin-dominant states can co-exist, they often alternate because of an event (e.g. flooding, marine heatwave), resulting in increased or decreased population densities of urchins or kelp (Stewart and Konar 2012). The natural tipping points of urchin barrens and kelp gardens may be stable in nature (Kriegisch et al. 2016). However, the true drivers behind what causes the environment to shift between kelp gardens and urchin barrens are st0ill not fully understood within New South Wales (Fig. 1).

Diagram showing unidentified factors influencing the transitions between a kelp garden and an urchin barren (Beisner et al. 2003).

The overarching aim of this study is to use two different information systems (Indigenous Traditional Knowledge and habitat mapping) to identify common emerging themes of the role of urchins in modifying NSW marine ecosystems. There is a distinct lack of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in the scientific literature that limits understanding of the role that C. rodgersii plays on the NSW South Coast (Przeslawski et al. 2025). This is the first study on Centrostephanus that utilises yarning within its methodologies. This is significant, because it could provide crucial information that may assist in future fisheries management (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010; Shay 2019; Barlo et al. 2021; Kennedy et al. 2022).

Yarning circles are an informal way of discussion, where the participant and researcher ‘visit’ different areas of interest, and the researcher builds candour and trust through this process (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010). Traditionally, Aboriginal people would use yarning as a way of storytelling; a yarn is always reciprocal and an open dialogue (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010). Although this structure is informal, it is purposeful and has the objective to gain information. Using this yarning method ensures cultural security, because it focuses on Indigenous Traditional communication techniques, rather than Western approaches (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010; Kennedy et al. 2022).

A yarning circle starts with a theme and continues to build knowledge on the basis of the stories and lived histories of the participants. The idea of a yarning circle is to allow knowledge to be shared from Elders to the younger generations in a circular fashion, continually building on top of each other by Elders adding more into these themes as the ‘yarn’ continues. It creates space for Traditional Knowledge holders to share what they feel is relevant to them, rather than being told what is relevant, which often makes connections between organisms and aspects of the environment that may not have been seen within Western academia. Yarning was the most appropriate method to be used in this study, because it is a culturally safe, and has been used in previous studies with effective results (Shay 2019; Barlo et al. 2021; Gibbs et al. 2024).

‘Braiding’ is a framework that allows multiple knowledge systems to stand alone in their own value and be woven together in a way that allows readers to see parallels in what is being portrayed (Henri et al. 2021). It enables readers to identify synergies between two different knowledge systems (Wilcox et al. 2023), including strengthening current understandings of modern ecological problems (Wilcox et al. 2023). The aim of this framework was to braid Traditional Knowledges with survey and mapping data of kelp and urchin dynamics. The results were divided by the three core themes that emerged from the yarning circles and were supported with scientific literature and habitat mapping results from the study.

We applied Traditional Knowledge from yarning circles and Western knowledge from habitat mapping to (i) identify the key themes related to barrens and kelp arising from Traditional Knowledges, (ii) assess the dynamics of barrens over time using existing Western science datasets, and (iii) braid Traditional Knowledges with survey and mapping data of kelp beds and urchin barrens. It is anticipated that the braiding of Traditional Knowledges and Western science in this study will extend the current timeline of knowledge regarding urchin and barren dynamics and establish whether current NSW barren spatiotemporal patterns described using Western science correspond to Traditional Knowledges.

Materials and methods

Traditional Knowledge Owners

The Traditional Knowledges component of this study was conducted through a series of yarning circles with Walbunja Traditional Owners. Walbunja Traditional Owners knowledge sharing was important to this study, because it provided a new perspective to the traditional Western methodologies of understanding urchin barrens. Additionally, Walbunja Traditional Owners hold an inextricable connection to the water and are known as ‘saltwater people’. The cultural practices of diving, fishing, swimming and being around the water means that the Walbunja people understand the marine ecosystems deeply and can extend current timelines. Their knowledge has neglected to be included in previous studies.

Throughout this study, terms will be used to describe the positionality of each Traditional Owner involved in the yarning circles; these terms are used within the Walbunja community to distinguish them from Western groups and are not formal terms. ‘Cultural diver’ refers to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person who regularly dives in the waters and engages in traditional methods of collection, cleaning, trading, etc. A ‘cultural commercial diver’ is a term used to distinguish an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander commercial diver from non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islandercommercial divers; this can hold different meaning to different people. A ‘commercial diver’, within the context of this paper, simply refers to non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and organisations that dive for monetary purposes on a large scale.

Study sites

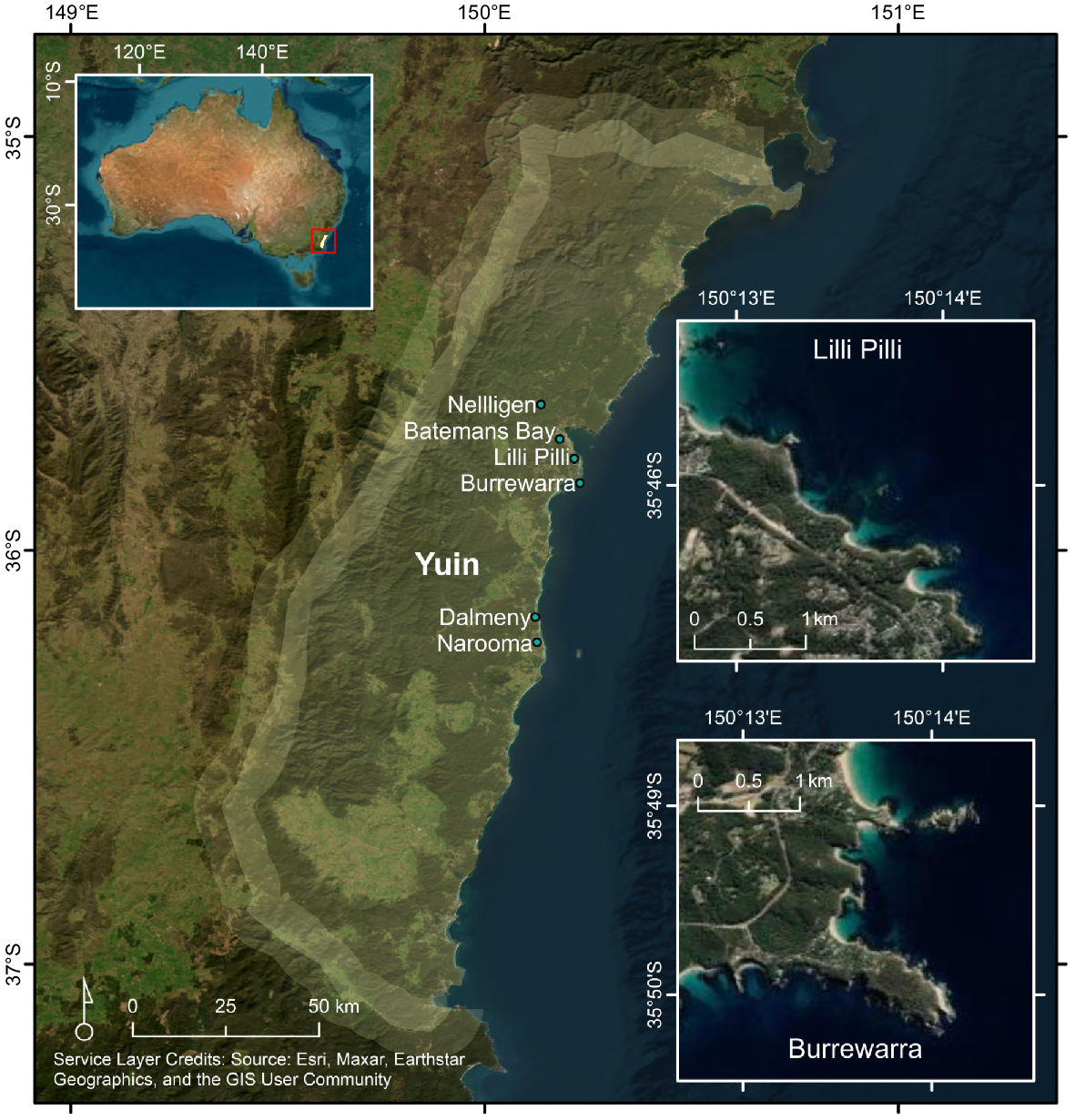

Yarning circles were conducted within the Yuin Nation, and the most recently agreed on boundaries of the Yuin Nation are from Jervis Bay to the Eden, although the boundaries are not fixed (Fig. 2). Habitat mapping data were collated from two locations on the South Coast of New South Wales, Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra: these study sites were chosen on the basis of availability of underwater visual census imagery provided by Department of Primary Industries (DPI) and associated aerial imagery. Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra are located within the Yuin Nation, on Walbunja Country. Therefore, the findings of the yarning circles were relevant to the sites chosen. Additionally, The NSW Government established the classification of zones within NSW Marine Parks through the NSW Marine Parks Act 1997 (Beeton et al. 2012). Burrewarra is a sanctuary zone, meaning that all commercial fishing is prohibited. However, Lilli Pilli is a habitat protection zone, meaning that commercial fishing is permitted, including the commercial fishing of abalone (Department of Primary Industries 2018).

Location map of aerial imagery sites (Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra) within the Yuin Nation (on Walbunja Country). The border shown in this figure is not exact and the boundaries are not fixed (Horton 1996).

Yarning circles

In this study, three yarning circles were conducted:

Yarning circle 1 occurred on the 21 June 2023 on a tour boat from Batemans Bay to Nelligen. A total of four Walbunja Traditional Owners recounted shared personal experiences of urchin barrens, kelp gardens and related ecological habitats and impacts.

Yarning circle 2 occurred on the 9 August 2023 Narooma at Wagonga Inlet. Two Walbunja Traditional Owners had a robust discussion centred around urchin barrens and related ecological impacts.

Yarning circle 3 occurred on the 9 August 2023, following the previous yarning circle, in Dalmeny. Two Walbunja Traditional Owners, who are both cultural divers in the local area, engaged in a yarn regarding urchins.

With communities around Australia, and in this case the Walbunja Traditional Owners, modern and commonly used contact methods do not always suit, particularly as many community members do not have access to email or telephones. To host the three yarning circles, communication approaches that Walbunja Traditional Owners could access and were comfortable with were used, such as word of mouth and face-to-face meetings. Each yarning circle had an intended duration of 1 h; however, this may have extended if the Traditional Owners wanted to continue communicating; and no one was expected to stay for the duration of the yarning circle.

The timeline of these yarning circles were generally referring to 1950s onward. The third yarning circle may date back further than this, due to the age of one of the cultural divers, as well as their stories in regard to their parents’ observations and lived experiences. Each yarning circle initiated with a broad conversation associated with the research topic; this then allowed the participants to naturally lead the conversation and highlight the key themes and concerns from the group. These yarns made sure to return to topics or themes, providing all participants an opportunity to share by expressing their knowledge about the environment and allowed the Traditional Owners to control the yarn, ensuring it was associated loosely to sea urchins, barrens, and kelp.

The control of the yarning circle by the Traditional Owners is the culturally appropriate way for the yarning to occur and allows the Traditional Owners to comfortably progress without losing their train of thought because of interruptions and questions. This also allows for the sharing of stories, practices, open dialogue about environmental factors, and Traditional Knowledge of interactions. Yarning circles were recorded through the Zoom H3-VR Handy Recorder and then processed. Processing is creating a written transcript, and then analysing each yarning circle to identify the major themes and then tying these major themes together from all three yarning circles to understand the commonalities. These common themes were then used to ‘braid’ with Western knowledge systems, including existing literature and habitat mapping, to form a collective understanding of the sites of this study.

Habitat mapping

Classification of features in urchin-dense areas was undertaken as a proof-of-concept using aerial photography extracted from NearMaps at Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra (location of sites shown in Fig. 2). Imagery was selected on the basis of clarity, with care taken to minimise whitewash, artefacts in the water and cloud cover effects. Applying this criterion for image selection meant that suitable images were dated from 2018 to 2022 (Supplementary material Fig. S1–S4).

Using eCognition (ver. 10.3.1, see https://geospatial.trimble.com/en/products/software/trimble-ecognition), images were segmented using object-based image analysis (OBIA) approaches, and segments were then classified as gravel and sand, land, rock, shallow water, submerged rock, underwater vegetation, water or white water. The segmentation products were subsequently improved by merging adjacent segments to create discrete classified polygons using ArcGIS Pro (ver. 3.2, see https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/get-started/download-arcgis-pro.htm). Maps for each image classification at each site were prepared and the extent of each class in each image was quantified to analyse temporal dynamics. Urchin barrens were not included as a class in the segmentation process, owing to the difficultly differentiating urchin barrens from other habitats through aerial imagery alone. The ground-truthing was utilised to confirm the presence of barrens after the classification was complete. See Fig. 3 for the workflow used to collect and classify the imagery for this study.

Different approaches for ground-validation of habitat maps were undertaken at each study site, with the approach being dependent on availability of validation data. Underwater imagery was available for Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra and this served as a means of establishing whether substrates were barren or vegetated at the time of the underwater survey. Of particular importance for validation was an unpublished pilot survey conducted in May 2023 by NSW Department of Primary Industries: Fisheries, which collected data from Burrewarra and Lilli Pilli used the following three methods: (i) perpendicular-to-shore UVC transects were completed following the method of Worthington and Blount (2003); (ii) parallel-to-shore UVC transects were completed following Method 2 used by the Reef Life Survey (Edgar and Stuart-Smith 2014); and (iii) UVC quadrats of 2 × 2 m of rocky reef were surveyed. Geospatially located imagery arising from these surveys were compared to classified maps at Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra and used to confirm the current existence of urchin barrens in the area (Fig. S5–S10).

Results

Yarning circles

Three yarning circles were completed with a varying number of participants. Detailed descriptions of the yarning circles can be found in Supplementary material. The yarning circles showed the following key concerns regarding urchin barrens on the NSW South Coast (full details in Supplementary material):

The declining numbers of culturally significant species (cuttlefish, Sepia apama; abalone, Haliotis rubra; snapper, Pagrus auratus; and lobster, Jasus edwardsii) were discussed in relation to environmental impacts since the 1950s, including marine protected areas (MPAs) and commercial fishing. Abalone is an integral cultural species that has been identified through personal observations when diving as significantly declining. Lobsters were also mentioned as being a key species that has been reduced in both size and density over the past few decades.

The role of sanctuary zones and MPAs was complex. MPAs were identified to be of a benefit in one yarning circle, discussing an increase in overall biodiversity. However, the discussion also identified barrens that exist within MPAs to be an artefact of overfishing. Most Traditional Owners discussed sanctuary zones or MPAs as restricting the right to cultural fishing.

Commercial diving was linked to removal of large predators and having negative effects on cultural fishing. The impact of commercial fishing on culture was identified to be due to reducing the number of culturally significant species and a lack of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander involvement and consultation in the industry.

These concerns were based on personal observations through extensive fishing and diving in local sites and should be taken into consideration in future studies on Centrostephanus rodgersii. There continues to be a gap in literature and understanding on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives of this issue. Although different approaches are used for Traditional Owners in knowledge sharing, many insights can be gained from understanding its value and actively listening to what is being said; Indigenous Traditional Knowledge ‘is often distinct from Western science in motivation and approach, but there are shared conceptual foundations that can support productive and mutually beneficial collaborations’ (Jessen et al. 2022, p. 93).

Habitat mapping

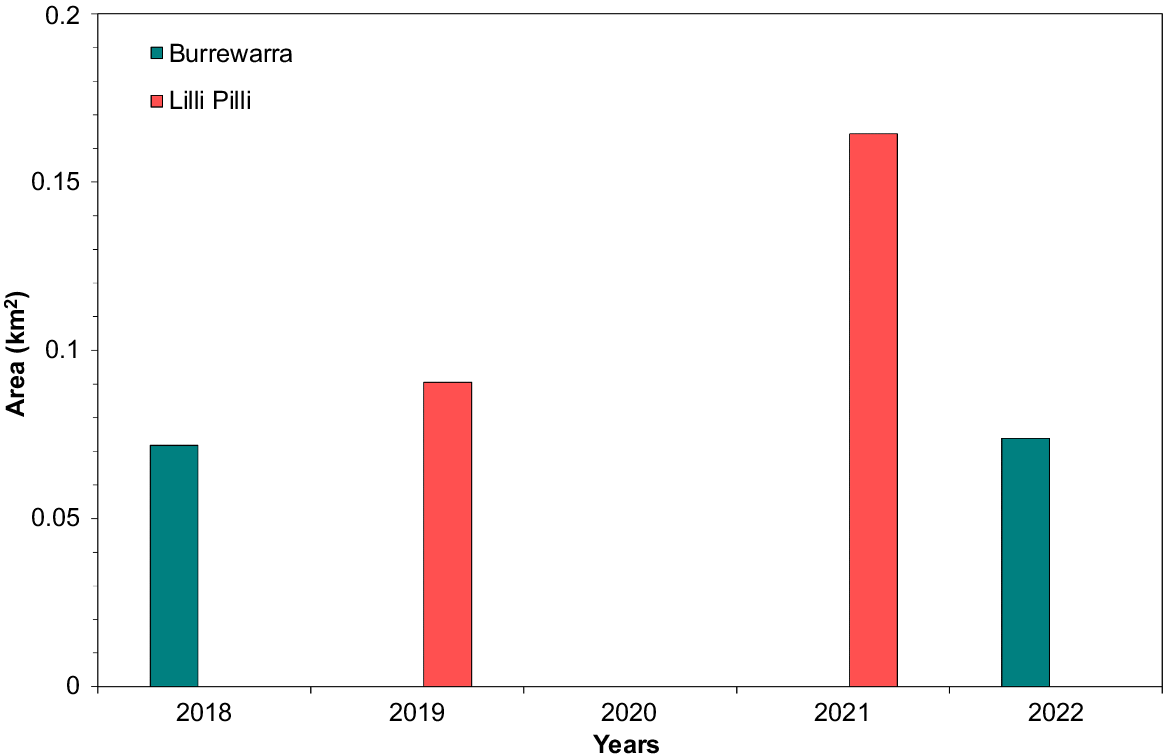

Suitable aerial imagery for Lilli Pilli was limited, reducing the frequency mapping and the capacity to establish recent temporal trends. Nevertheless, Lilli Pilli showed an increase in underwater vegetation around the northern rocky platform in 2021 (Fig. 4). There was an overall increase in underwater vegetation in 2021, with an area value of 0.164 km2, compared with 0.09 km2 in 2019. Underwater validation imagery confirmed that barrens were interspersed with small patches of kelp and turfing algae at this study site. Moreover, C. rodgersii can be seen in the rocky crevices (Fig. S5–S7). The classification of underwater imagery and UVC imagery for the Lilli Pilli site indicates that much of the substrate is likely to be a mosaic of macroalgae and barrens. On the basis of the results of UVC imagery and object-based image analysis (OBIA) mapping, urchin barrens in Lilli Pilli are likely to be dynamic in their distribution over time. The OBIA alone was unable to decipher between varying types of vegetation, and the lack of available clear imagery reduced the period of vegetation abundance through time.

Burrewarra showed a fluctuation in underwater vegetation between the Years 2018 and 2022 (Fig. 4). The Western region of 2022 imagery shows an absence of vegetation, which is also reflected in the OBIA results. Additionally, both years show speckling of vegetation, rather than large distinct areas. Burrewarra underwater imagery transects conducted perpendicular-to-shore in May 2023 showed predominantly mosaics of macroalgae and rock encrusted with crustose coralline algae as well as extensive sand flats (Fig. S8–S10). On the basis of the underwater visual census imagery for this study site, it was presumed that this speckled vegetation was likely to be mosaics of macroalgae, similarly to Lilli Pilli. On the basis of similar observations of speckled vegetation at both Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra, it was presumed that the classification provided a reasonable indication of the abundance of underwater vegetation. Vegetation abundance was higher in 2022, with a normalised area value of 0.074 km2, compared with 0.071 km2 in 2018 (Fig. 5). These results indicated that the barren habitat in Burrewarra is likely to be dynamic in vegetation distribution over time.

Discussion

Yarning circles

The topics identified through the three yarning circles were as follows: abalone declines; sanctuary zones; fisheries resources, including cuttlefish (S. apama), abalone (H. rubra), snapper (P. auratus) and lobster (J. edwardsii); commercial fishing; and loss of culture. These can be grouped into three core themes, namely, decline of cultural foods (resulting in a loss of culture), sanctuary zones and commercial fishing. The three themes identified through the yarning circles were significant to the existence of urchin barrens on the South Coast, each for different reasons. The decline of cultural foods was linked to overfishing of predatory fish, as well as the invasion of C. rodgersii, preventing other species such as abalone, to inhabit the area. Sanctuary zones were considered preventative to practising cultural fishing (Fig. 6), and the barrens within these zones were identified as a possible ‘artefact’ of overfishing. Commercial fishing was discussed as the primary reason for the removal of top predators that maintain the urchin population.

The Batemans Bay Marine Park zoning. Burrewarra is located within a sanctuary zone, and Lilli Pilli (north of Burrewarra) is located in the habitat protection zone (Department of Primary Industries 2018).

The decline of cultural foods was identified because of overfishing, which Traditional Owners said resulted in higher urchin abundances and associated barrens. Views on sanctuary zones were divided regarding whether they enabled cultural practice; however, all yarning circles identified that barrens still existed within them, and commercial fishing was intertwined throughout the discussions. A lack of consultation and involvement with the commercial fishing industry has resulted in distrust; the Traditional Owners hold concerns about barrens and believe these are a relic of unsustainable commercial fishing.

Traditional Owners had observed a change in their local areas in which they dive and fish, and this was their primary concern. There were several concepts in Western literature that were discussed in the yarning circles, including the observation that abalone no longer inhabit urchin-dominated areas (Strain and Johnson 2009; Chick et al. 2013; Strain et al. 2013), a reduction in the predator size required to consume urchins (Westcott et al. 2022), and the impacts of weather events on kelp dense areas. Further, there were clear links between the emerging themes identified through the yarning circles, despite the yarns being among different groups and conducted at different times and locations. However, it is important to recognise the differences in responses, including attitudes towards sanctuary zones. These responses included some Traditional Owners recognising sanctuary zones as an important factor in preserving biodiversity, and other groups of Traditional Owners viewing the sanctuary zones are a hindrance to practising culture. This is one example of different understandings between community members, and it is paramount to recognise this in Marine Park management and decision making.

Habitat dynamics

Barrens were dynamic in their distribution over time, but the accuracy of assessments were likely to have been improved because of the availability of underwater imagery. The UVC for Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra improved results, because it confirmed the presence of barrens and allowed for the distinction between different types of vegetation. Aerial imagery quality was limited in all sites, owing to weather conditions contributing to water turbidity. Although manual classification of polygons improved this limitation, accuracy was still reduced overall.

Both Burrewarra and Lilli Pilli vegetation abundance showed a fluctuation of vegetation among years overall. Lilli Pilli may have comparatively larger fluctuations, but only 2 years of imagery were available for Lilli Pilli, which made it difficult to deduce meaning from the results because of it being poor temporal resolution. Both sites are mosaics of barrens, macroalgal beds, and turfing algae, with larger barrens expanses being likely at Lilli Pilli in recent years. Mapping showed small fluctuation of underwater vegetation abundance, which could be presumed to be kelp; however, the underwater vegetation may also be turf algae.

There was a strong alignment between discussion in the yarning circles and the habitat dynamics identified through UVC imagery and OBIA mapping. Urchins were abundant in crevices in the rocks. The yarning circles discussed rocky crevices being invaded by urchins, which prevents other species from inhabiting the crevices, such as lobsters and abalone. Additionally, the lack of macroalgae at both sites aligned with the decline of culturally significant species that rely on kelp in various ways.

Braiding two knowledge systems; Traditional Knowledges and Western science

Braiding demonstrates the synergies and alignments that may emerge when using two knowledge systems. In this study, we used yarning circles and habitat mapping to improve our understanding of the temporal dynamics of urchin densities and the development of barrens on the South Coast of New South Wales.

The decline of cultural foods such as abalone, lobster and cuttlefish were the first, and primary, concern held by the Traditional Owners. Many of the Traditional Owners have been diving and fishing in the same spots for ~65 years, and their diets have been primarily seafood. The reduction of their food sources is believed to be caused by cascading impacts of commercial fishing on their local diving and fishing spots. Considering the Traditional Owners avoid barrens and do not dive in or around them, this has notably reduced the areas available to dive in. Urchin barrens were identified as an indicator that the ocean was unhealthy, because the species that were once in the local areas, are now reduced in size, abundance, and are in deeper depths than what they have been previously. The type of commercial fishing these Traditional Owners were primarily referring to is the fin fish and lobster industry. Notably, however, there is also a substantial commercial fishery on abalone (Novaglio et al. 2018). This could be another factor affecting the abalone population mentioned, and should be considered in future studies that are assessing the impacts of commercial fishing industry on C. rodgersii. Throughout the three yarning circles, the importance of abalone and lobster to the Yuin Traditional Owners, particularly as a cultural food source, was identified. Emerging from the yarns was concern for the observed decline in abalone and lobster, despite the drivers being unclear or unknown (the following quotations have been sourced from Walbunja Traditional Owners):

diving spots where we used to get abalone are deserted. Urchins have come in abundance … our cultural food is abalone and periwinkles

Something which should be naturally occurring such as abalone, if something invades it, it will flee.

This sentiment was echoed by the second and third yarning circles:

Dalmeny used to be rich with abalone … haven’t seen a decent sized abalone in many years

we didn’t used to have to dive. We waited until low tide and got 10–15 abalone. We moved into the water because we had no choice. Then I had to learn how to dive out deep in the 70s

now, there’s nothing in the water. I have to go 50–100 m out … it’s a lot different

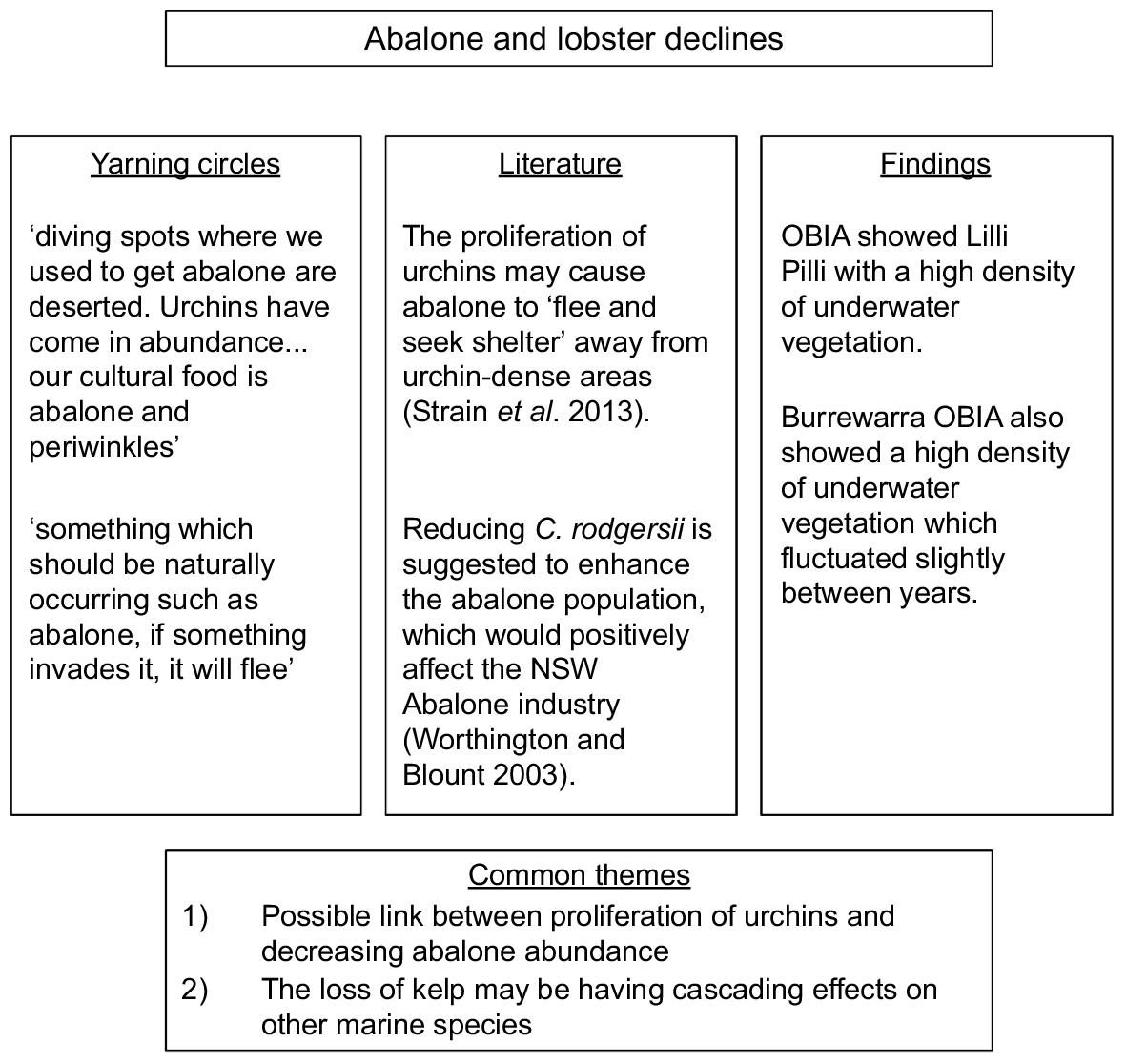

Abalone abundance is declining in New South Wales (Chick et al. 2013), possibly owing to species such as abalone that have been known to ‘fleeing and seeking shelter’ in the presence of urchins, (Johnson et al. 2005; Strain et al. 2013), supporting the findings of the yarning circles. Abalone flee due to the urchin being a superior competitor (Strain and Johnson 2009; Strain et al. 2013). Kelp is a key habitat for both lobster and abalone (Layton et al. 2020) and Burrewarra and Lilli Pilli UVC showed limited kelp, but a high abundance of macroalgae. Although these sites were not discussed in the yarning circles explicitly, these are well known popular diving and fishing areas for the Walbunja people, particularly Burrewarra. Reduced kelp was identified as one potential driver to the decreases in lobster population density in the yarning circles:

lobsters are only little … the big ones have nothing to eat, and nowhere to nest or hide

urchins were there. but they were nothing like this. You can’t put your hand in your holes to get lobsters now without urchins

Although this study did not specifically look at the densities of abalone along the South Coast, it did identify the presence of urchin barrens in Lilli Pilli and Burrewarra. A lack of aerial photography in earlier years meant that detection of differences in underwater vegetation over time was unable to be achieved; however, yarning circles indicated a decline in abalone and lobster observed since the 1970s, which occurred alongside the observation of declining kelp abundance. Fig. 7 shows the parallels between the yarning circle results, literature, and what was identified through this study in relation to the theme of abalone and lobster declines.

Conceptual diagram of ‘braiding’ for yarning circle theme: abalone and lobster declines. Literature sources are Worthington and Blount (2003) and Strain et al. (2013).

Sanctuary zones

Whether sanctuary zones prevented cultural practice was a point of discussion throughout all yarning circles. Some Traditional Owners observed a difference between sanctuary zones and other areas, noting that they observed more biodiversity, despite the presence of barrens. However, it was generally agreed that urchin barrens within MPAs did not indicate that they were naturally occurring but were instead an artefact of a long history of unsustainable commercial fishing. Although this may seem to contradict the current paradigm suggesting that barrens are a representative habitat of rocky reefs within NSW (Underwood et al. 1991; Kingsford and Byrne 2023), it may instead reflect the shifting baseline phenomenon (Atmore et al. 2021).

The first yarning circle identified sanctuary zones as negative:

implementing sanctuary zones in cultural areas has prevented us from managing our Country, it was a healthy relationship. We shouldn’t be harvesting the same areas over and over … it’s like a crop farm; if you don’t rotate your crops, your land is degraded

setting up something like a sanctuary zone can have detrimental effects, and so can overfishing

This differed from the results of the second yarning circle, which identified sanctuary zones as increasing biodiversity:

…in a marine park you see a range of size and abundance in fish species … once you get out of the marine park, the ecosystem degrades, I see it up north closer to Mystery Bay

Marine park is doing its job, because the fish are the same as what I used to catch

Marine parks are healthy

Therefore, the yarning circles showed a conflict in perspective on marine parks and sanctuary zones.

The intention of habitat protection zones is to prevent harm to the habitat, and Lilli Pilli is situated in a habitat protection zone. Although recreational fishing is permitted, extensive fishing such as trawling is prohibited (Department of Primary Industries 2018). Importantly, commercial fishing is allowed with some constraints in place. The commercial fishing methods are limited but include the removal of abalone being permitted. Sanctuary zones provide the highest protection level, with the only activities permitted being activities that do not involve the removal or harm of any marine life, and Burrewarra is situated in a sanctuary zone (Department of Primary Industries 2018, 2020). Burrewarra and Lilli Pilli have some barrens aligning with current literature, indicating that barrens exist throughout most of New South Wales rocky reefs (Przeslawski et al. 2023). There are conflicting perspectives between Traditional Owners on whether no-take zones are an appropriate way of management, and this could be considered in future studies. The links among the themes emerging among yarning circles, habitat mapping and literature are presented in Fig. 8.

Conceptual diagram of ‘braiding’ for yarning circle theme: sanctuary zones. Literature sources are Sangil et al. (2012) and Przeslawski et al. (2023).

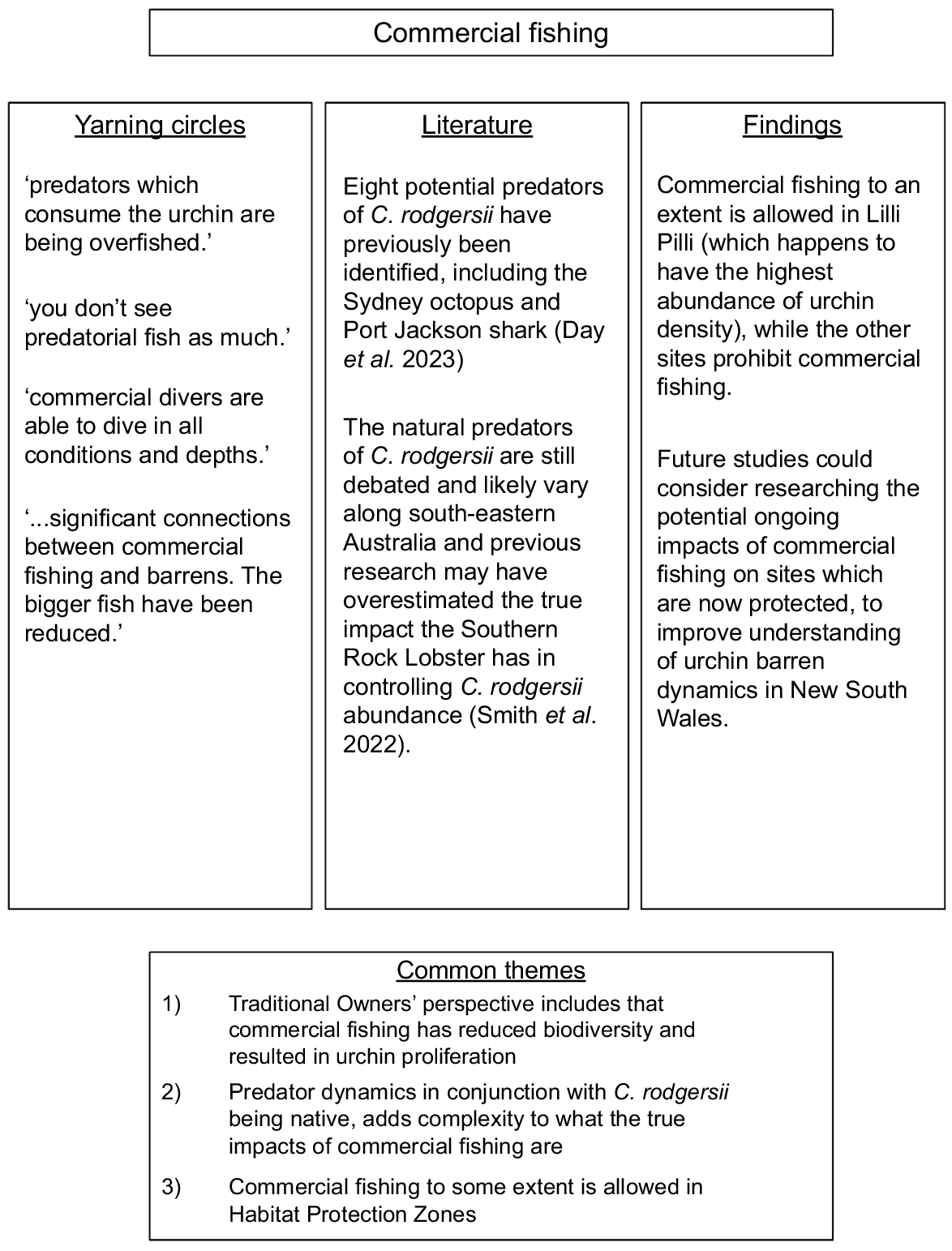

Commercial fishing

Commercial fishing was identified as a primary driver for urchin barrens in all three yarns, and the primary concern was regarding the removal of large predators. Gropers (A. viridis) and snapper (P. auratus) were identified to be key predators, which the Traditional Owners identified as reduced in abundance and size along the coast; theories behind their reduction were commercial fishing and competitive or recreational fishing, which often targeted larger and slow-moving gropers. Sustainable commercial fishing was discussed as a possibility if the commercial fishing industry consulted with the broader Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and allowed for more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander involvement in the management of cultural areas.

Although commercial fishing was mentioned in the first yarning circle, it was not distinguished into a key theme, because it was relatively brief. However, the topic was raised as a concern across all three yarns:

predators which consume the urchin are being overfished

you don’t see predatorial fish as much

commercial divers are able to dive in all conditions and depths

The discussion of barrens and what could be contributing to their high abundances was also centred around commercial fishing:

…significant connections between commercial fishing and barrens. The bigger fish have been reduced

barrens are a result of overfishing and mismanagement

Sustainable commercial fishing was discussed in the second yarning circle, identifying different methods of fishing as a possible contributor to being sustainable or unsustainable:

They have the equipment to dive deeper than us, so it doesn’t make sense for them to come in shallow. We free dive in shallow water and that’s what makes us sustainable, we can only hold our breath for so long.

The Western science component of this study did not address the relationship between commercial fishing and barrens in NSW, and the existing literature on the topic is limited (Turnbull et al. 2021). Although fisheries exploitation and climate change are theorised to be key influences of increasing abundance of urchins, resulting in urchin barrens (Melis et al. 2019), it could also be possible that this does not apply to New South Wales. The natural predators of C. rodgersii in NSW include fish, lobster, and cephalopods (Day et al. 2023) and likely vary along south-eastern Australia. The braiding of the yarning circles, literature and the findings of this study are shown in Fig. 9.

Conceptual diagram of ‘braiding’ for yarning circle theme: commercial fishing. Literature sources are Smith et al. (2022) and Day et al. (2023).

On the basis of yarning circle results, commercial fishing is believed to have ongoing impacts to all sites, owing to cascading effects of removing urchin predators. Commercial fishing in other areas could still be having impacts on sites where commercial fishing is prohibited. Future studies could consider further research within MPAs to improve understanding of urchin barren dynamics in New South Wales.

Conclusions

Employing two information systems to explore the correlations between habitat mapping and Traditional Knowledge offers an effective strategy for bridging the existing gap in literature concerning urchin barrens in New South Wales. The findings of this study have extended the existing timeline of urchin barren dynamics by using oral histories and demonstrated the importance of utilising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in future fisheries management. Braiding the two knowledge systems identified that although the approaches may vary, the understanding between the two can be similar. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander involvement in research of C. rodgersii on the South Coast of NSW is imperative to gaining a better understanding of the habitat dynamics. Walbunja people are connected to the water and can offer new insight through positive partnerships with researchers.

Position statements

Kyah Chewying

I am an Indigenous Walbunja woman with a deep, active engagement within the Walbunja community. My identity and experiences as an Indigenous person have profoundly shaped my perspective, directly influencing my choice of this research topic and the methodologies applied. I recognise that my connection to my community and my cultural knowledge have guided not only my research focus but also the way I approach, interpret, and present findings. My commitment to centring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives and honouring Traditional Knowledge systems is central to this work. I acknowledge that this positionality comes with responsibilities to represent and respect my community’s values, knowledge, and voices, and I am mindful of how this positionality may influence my interpretations and interactions within the broader academic context.

Dr Mitchell Gibbs

As a proud Dunghutti man through kinship, lecturer, postdoctoral and Fulbright fellow at the University of Sydney, my heritage and cultural background deeply inform my research approach and purpose. I have dedicated my work to amplifying the stories, experiences, and knowledge of traditional knowledge holders, particularly in relation to shellfish and coastal ecosystems. My commitment to integrating traditional knowledge within academic research stems from a belief that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing are essential for a fuller understanding of environmental and ecological relationships. I recognise that my positionality as an Indigenous researcher brings both responsibilities and unique insights; I aim to bridge traditional and Western knowledge systems with respect, integrity, and a focus on genuine collaboration.

Dr Rachel Przeslawski

As a an Australian–American marine ecologist with previous experience advising the NSW government and leading the Australian Marine Sciences Association, I recognise the significance of utilising Traditional Knowledges in ecological research. My background has shown me how diverse perspectives enhance our understanding of marine and benthic ecosystems. I am a strong advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledges in scientific research to support healthy Country. I am committed to fostering positive partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities with respect, reciprocity, and a dedication to genuine knowledge exchange, and apply these principles to research efforts that not only value but also centre Traditional Knowledge through comprehensive science that reflects both ecological and cultural dimensions.

Dr Kerrylee Rogers

As an Australian environmental scientist and lecturer at the University of Wollongong, with a focus on coastal wetlands and climate change mitigation, I acknowledge the privilege and responsibility I carry within the field of environmental science. I am committed to supporting efforts that bridge Western scientific approaches with Traditional Knowledges, recognising that these perspectives are essential to achieving meaningful and holistic solutions to environmental challenges. In my role as a collaborator, I fully support the lead author’s exploration and inclusion of Traditional Knowledges within a Western scientific format. I understand the importance of elevating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and perspectives, and I aim to approach this work with respect, humility and a commitment to learning.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article and accompanying online supplementary material.

Conflicts of interest

Rachel Przeslawski and Kerrylee Rodgers are both Editors of Marine and Freshwater Research but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

Kyah Chewying receives a University Postgraduate Award Indigenous (UPAI) from University of Wollongong to support her through her through a PhD. Kyah was supported by the School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences and NSW Department of Primary Industries throughout her honours year. Kyah was also supported through an Indigenous Fellowship Program with CSIRO. The writing of this paper was supported by a First Nations Internship from the Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to the First Nations peoples who were a cornerstone to this research, and are knowledge holders, storytellers, and custodians of the Land and Sea. We greatly appreciate your contributions to this study. We are grateful to the NSW DPI Fisheries field team who collected the 2023 urchin data used in this study (Roger Laird, Jeremy Day, Sham Eichmann). Greg West and Tim Glasby provided advice and training on habitat mapping techniques used in this study.

References

Atmore LM, Aiken M, Furni F (2021) Shifting baselines to thresholds: reframing exploitation in the marine environment. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, 742188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Balemi CA, Shears NT (2023) Emergence of the subtropical sea urchin Centrostephanus rodgersii as a threat to kelp forest ecosystems in northern New Zealand. Frontiers in Marine Science 10, 1224067.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barlo S, Boyd WE, Hughes M, Wilson S, Pelizzon A (2021) Yarning as protected space: relational accountability in research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 17(1), 40-48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Beeton R, Buxton C, Cutbush G, Fairweather P, Johnston E, Ryan R (2012) Report to the Independent Scientific Audit of Marine Parks in New South Wales. (NSW Department of Primary Industries and Office of Environment and Heritage) Available at https://www.marine.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/739434/Report-of-the-Independent-Scientific-Audit-of-Marine-Parks-in-New-South-Wales-2012.PDF

Beisner BE, Haydon DT, Cuddington K (2003) Alternative stable states in ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 1(7), 376-382.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bessarab D, Ng’andu B (2010) Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3, 37-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Byrne M, Gall ML, Campbell H, Lamare MD, Holmes SP (2022) Staying in place and moving in space: contrasting larval thermal sensitivity explains distributional changes of sympatric sea urchin species to habitat warming. Global Change Biology 28(9), 3040-3053.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chick RC, Worthington DG, Kingsford MJ (2013) Restocking depleted wild stocks: long-term survival and impact of released blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra) on depleted wild populations in New South Wales, Australia. Reviews in Fisheries Science 21(3-4), 321-340.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coleman MA, Kennelly SJ (2019) Microscopic assemblages in kelp forests and urchin barrens. Aquatic Botany 154, 66-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Curley BG, Kingsford MJ, Gillanders BM (2002) Spatial and habitat-related patterns of temperate reef fish assemblages: implications for the design of Marine Protected Areas. Marine and Freshwater Research 53(8), 1197-1210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Day J, Knott NA, Ayre D, Byrne M (2023) Effects of habitat on predation of ecologically important sea urchin species on east coast Australian temperate reefs in tethering experiments. Marine Ecology Progress Series 714, 71-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Day JK, Knott NA, Swadling DS, Ayre DJ, Huggett MJ, Gaston TF (2024) Investigating the diets and condition of Centrostephanus rodgersii (long-spined urchin) in barrens and macroalgae habitats in south-eastern Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series 729, 167-183.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of Primary Industries (2018) Batemans Bay Marine Park Zoning Map. (NSW Government) Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/656288/Batemans_Marine_Park_Zoning_Map.pdf

Department of Primary Industries (2020) Bushrangers Bay Aquatic Reserve. (NSW Government) Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/marine-protected-areas/aquatic-reserves/bushrangers-bay-aquatic-reserve

Edgar GJ, Stuart-Smith RD (2014) Systematic global assessment of reef fish communities by the Reef Life Survey program. Scientific Data 1, 140007.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gibbs MC, Parker LM, Scanes E, Ross PM, Przeslawski R (2024) Recognising the importance of shellfish to First Nations peoples, Indigenous and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in aquaculture and coastal management in Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research 75(4), MF23193.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Glasby TM, Gibson PT (2020) Decadal dynamics of subtidal barrens habitat. Marine Environmental Research 154, 104869.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Henri DA, Provencher JF, Bowles E, Taylor JJ, Steel J, Chelick C, Popp JN, Cooke SJ, Rytwinski T, McGregor D, Ford AT, Alexander SM (2021) Weaving Indigenous Knowledge systems and Western sciences in terrestrial research, monitoring and management in Canada: a protocol for a systematic map. Ecological Solutions and Evidence 2(2), e12057.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Horton DR (1996) Map of Indigenous Australia. (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies) Available at https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/map-indigenous-australia

Jessen TD, Ban NC, Claxton NX, Darimont CT (2022) Contributions of Indigenous Knowledge to ecological and evolutionary understanding. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 20(2), 93-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Johnson CR, Link SD, Ross J, Shepherd S, Miller K (2005) Establishment of the long-spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) in Tasmania: first assessment of potential threats to fisheries. FRDC Project number 2001/044. (School of Zoology, Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute, University of Tasmania) Available at https://data.imas.utas.edu.au/attachments/5ef4b940-86a3-11dc-a9fc-00188b4c0af8/FRDC_FINAL_report_Johnson__2001_044____1.pdf

Kennedy M, Maddox R, Booth K, Maidment S, Chamberlain C, Bessarab D (2022) Decolonising qualitative research with respectful, reciprocal, and responsible research practice: a narrative review of the application of Yarning method in qualitative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. International Journal for Equity in Health 21(1), 134.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kingsford MJ, Byrne M (2023) New South Wales rocky reefs are under threat. Marine and Freshwater Research 74(2), 95-98.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kriegisch N, Reeves S, Johnson CR, Ling SD (2016) Phase-shift dynamics of sea urchin overgrazing on nutrified reefs. PLoS ONE 11(12), e0168333.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Layton C, Coleman MA, Marzinelli EM, Steinberg PD, Swearer SE, Vergés A, Wernberg T, Johnson CR (2020) Kelp Forest Restoration in Australia. Frontiers in Marine Science 7, 74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ling SD (2008) Range expansion of a habitat-modifying species leads to loss of taxonomic diversity: a new and impoverished reef state. Oecologia 156(4), 883-894.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ling SD, Johnson CR, Frusher SD, Ridgway KR (2009) Overfishing reduces resilience of kelp beds to climate-driven catastrophic phase shift. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(52), 22341-22345.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ling SD, Mahon I, Marzloff MP, Pizarro O, Johnson CR, Williams SB (2016) Stereo-imaging AUV detects trends in sea urchin abundance on deep overgrazed reefs. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods 14(5), 293-304.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mabin CJT, Johnson CR, Wright JT (2019) Physiological response to temperature, light, and nitrates in the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera, from Tasmania, Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series 614, 1-19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Melis R, Ceccherelli G, Piazzi L, Rustici M (2019) Macroalgal forests and sea urchin barrens: structural complexity loss, fisheries exploitation and catastrophic regime shifts. Ecological Complexity 37, 32-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Novaglio C, Smith ADM, Frusher S, Ferretti F, Klaer N, Fulton EA (2018) Fishery development and exploitation in South East Australia. Frontiers in Marine Science 5, 145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Perkins NR, Hill NA, Foster SD, Barrett NS (2015) Altered niche of an ecologically significant urchin species, Centrostephanus rodgersii, in its extended range revealed using an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 155, 56-65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pert CG, Swearer SE, Dworjanyn S, Kriegisch N, Turchini GM, Francis DS, Dempster T (2018) Barrens of gold: gonad conditioning of an overabundant sea urchin. Aquaculture Environment Interactions 10, 345-361.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Przeslawski R, Chick R, Day J, Glasby T, Knott NA (2023) Research Summary New South Wales Barren. (NSW Department of Primary Industries) Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1446991/Updated-Research-Summary-NSW-Barrens.pdf

Przeslawski R, Chick RC, Davis T, Day JK, Glasby TM, Knott N, Byrne M, Chiu MYJ (2025) A review of urchin barrens and the longspined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) in New South Wales, Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research 76(5), MF24149.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sangil C, Clemente S, Martín-García L, Hernández JC (2012) No-take areas as an effective tool to restore urchin barrens on subtropical rocky reefs. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 112, 207-215.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shay M (2019) Extending the yarning yarn: collaborative yarning methodology for ethical Indigenist education research. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 50(1), 62-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith JE, Keane J, Mundy C, Gardner C, Oellermann M (2022) Spiny lobsters prefer native prey over range-extending invasive urchins. ICES Journal of Marine Science 79(4), 1353-1362.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stewart NL, Konar B (2012) Kelp forests versus urchin barrens: alternate stable states and their effect on sea otter prey quality in the Aleutian Islands. Journal of Marine Biology 2012, 492308.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Strain EMA, Johnson CR (2009) Competition between an invasive urchin and commercially fished abalone: effect on body condition, reproduction and survivorship. Marine Ecology Progress Series 377, 169-182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Strain EMA, Johnson CR, Thomson RJ (2013) Effects of a range-expanding sea urchin on behaviour of commercially fished abalone. PLoS ONE 8(9), e73477.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomas LJ, Liggins L, Banks SC, Beheregaray LB, Liddy M, McCulloch GA, Waters JM, Carter L, Byrne M, Cumming RA, Lamare MD (2021) The population genetic structure of the urchin Centrostephanus rodgersii in New Zealand with links to Australia. Marine Biology 168(9), 138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Turnbull JW, Johnston EL, Clark GF (2021) Evaluating the social and ecological effectiveness of partially protected marine areas. Conservation Biology 35(3), 921-932.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Underwood AJ, Kingsford MJ, Andrew NL (1991) Patterns in shallow subtidal marine assemblages along the coast of New South Wales. Australian Journal of Ecology 16(2), 231-249.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Westcott DA, Fletcher CS, Chades I (2022) Strategies for the management of Centrostephanus rodgersii in Tasmanian waters. A report for the Abalone Industry Re-Investment Fund. CSIRO, Australia. 10.25919/35b0-hn89

Wilcox AAE, Provencher JF, Henri DA, Alexander SM, Taylor JJ, Cooke SJ, Thomas PJ, Johnson LR, Pelletier F (2023) Braiding Indigenous Knowledge systems and Western-based sciences in the Alberta oil sands region: a systematic review. Facets 8, 1-32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Worthington DG, Blount C (2003) Research to develop and manage the sea urchin fisheries of NSW and eastern Victoria. FRDC Project number 1999/128, October 2003, NSW Fisheries Final Report Series number 56. (NSW Fisheries: Sydney, NSW, Australia) Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/545642/FFRS-56_Worthington-and-Blount-2003.pdf