Connecting young people to Country through marine turtle conservation: exploring three case studies in Western Australia’s Pilbara region

Clodagh Guildea A * , Sabrina Fossette A , Tristan Simpson A , Sarah McDonald A , Natasha Samuelraj A , James Gee A , Suzanne Wilson B , Jane Hyland B , Dimitrov Atanas C , Susan Buzan D , Julian Tan D , Rebecca Mackin D , Jason Rossendell E and Scott Whiting A

A * , Sabrina Fossette A , Tristan Simpson A , Sarah McDonald A , Natasha Samuelraj A , James Gee A , Suzanne Wilson B , Jane Hyland B , Dimitrov Atanas C , Susan Buzan D , Julian Tan D , Rebecca Mackin D , Jason Rossendell E and Scott Whiting A

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

The world’s oceans are confronting many challenges, which are affecting threatened species such as marine turtles. To address these challenges, it is imperative that pro-environmental behaviors are cultivated in the wider community, and young people are provided opportunities to overcome socio-economic and geographical barriers to meaningfully experience nature. In the Pilbara region of Western Australia, Aboriginal Traditional Custodians share a deep connection and caring relationship with Country. Collaboration and partnership between Traditional Custodians and conservation programs are essential for empowering Aboriginal young people as future conservation leaders and to achieve long-term conservation goals. Western Australia’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, a government department, has been working with schools and community organisations across the Pilbara to support access to remote Sea Country and marine turtle conservation experiences for Aboriginal young people. By examining three case studies demonstrating the collaboration among the North West Shelf Flatback Turtle Conservation Program, West Pilbara Turtle Program, Waalitj Foundation, Onslow School and Roebourne District High School, this article explores the importance of building partnerships, providing additional on-Country opportunities for young people, and enabling future pathways for the longevity of long-term conservation programs and the health of the environment and communities.

Keywords: Aboriginal, behaviour, connection, conservation, education, First Nations, flatback turtle, Indigenous, marine turtle, nature, Sea Country, Traditional Custodians, youth.

Introduction

The world is changing at an unprecedented rate, with impacts from human activities affecting ecosystems and species in pervasive and irreversible ways (Corlett 2015). Our oceans are facing cumulative threats in the forms of temperature increase, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, pollution, resource exploitation, and biodiversity loss (Strand et al. 2022). Such is the challenge to sustain and preserve the ocean that the United Nations has declared 2021–2030 the critical ‘Ocean Decade’ to revolutionise science and trigger a change in humanity’s relationship with nature (Barbière 2023). It is understood that identifying and overcoming barriers to human behavior change globally, and promoting ocean stewardship is required to solve these complex challenges and ensure good governance into the future (Brodie Rudolph et al. 2020; Barbière 2023).

Australia is an island continent, with ~34,000 km of coastline abutting the Indian, Southern and Pacific Oceans. Of the eight capital cities, seven are based on the coast and 87% of the population live within 50 km of the ocean (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021). It is understood that exposure to nature, such as coastal environments, throughout childhood and adolescence not only improves the health and wellbeing of children but also influences the development of pro-environmental behaviors and attitudes into adulthood (Wells and Lekies 2006; Cheng and Monroe 2012; Keith et al. 2021).

Pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in children require maintenance and role-modelling if they are to continue this learning through adolescence to adulthood. In a study of 1000 students living in Sydney, Australia, Keith et al. (2021) identified a negative association between environmental behaviors and increasing age, with younger students (aged 8–11 years old) more strongly connected to nature than their older peers (aged 12–14 years old). These findings support previous studies of English, Swedish and Spanish students, which identified that in early adolescence young people begin to experience a disconnect from nature and engage in less pro-environmental behaviors; this has been coined the ‘adolescent dip’ (Olsson and Gericke 2016; Hughes et al. 2019; Richardson et al. 2019).

There are several suggestions to minimise the effects of the ‘adolescent dip’, such as the development of a robust environmental education curriculum in schools and providing meaningful (emotive and sensory) nature experiences for early adolescents (Olsson and Gericke 2016; Keith et al. 2021). Chawla and Cushing (2007) found that interactions between children and family role models who value nature strongly predict the child’s ongoing interests in the environment into adulthood, indicating that community culture and role-modelling are also significant factors supporting youth to maintain their connection to nature.

Country, connection and conservation

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples have lived in Australia for over 60,000 years and are considered the oldest surviving culture in the world. As of 2021, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people represented 3.8% of the Australian population. Regionally, the Pilbara in Western Australia is home to a much higher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, with 20.25% of the population identifying as Aboriginal1 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021). The cultural identities of Aboriginal Peoples are diverse, with distinct language groups built around community, culture and deep and spiritual connections with nature, their ‘Country’ (Reconciliation Australia 2021).

In the Pilbara, Aboriginal Peoples ‘are passionately attached to a sense of identity that comes from particular places and the wider land and waterscapes within which those places lie’ (Barber and Jackson 2011, p. 18). They actively connect themselves to Country through Traditional Lore, kinship relationships, and the sharing of Dreaming, knowledge and practices, underpinned by pro-environmental attitudes and strong values for sustaining and protecting Country as Traditional Custodians (Barber and Jackson 2011).

Aboriginal people still relate to the land that was inundated by the sea and regard it as their own. There are still significant places and connections to sea life that can be passed along for generations to come. [Suzanne Wilson, manager of Onslow Waalitj Foundation]

The forceful displacements, massacres and exclusions of Aboriginal Peoples from Country since European colonisation have resulted in reduced access for Aboriginal communities to Land and Sea Country2 today (Gregory and Paterson 2015; Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre 2024). Combined with the removal of children from Aboriginal families for the first half of the 1900s and the relocation of whole communities to missions, there has been significant trauma and loss of culture, language and knowledge throughout the Pilbara, with ongoing impacts to the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal Peoples today (Lowitja Institute 2020; Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre 2024). Nationally, these impacts are recognised as ‘gaps’ in life expectancy, mental health, education and employment outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2024). Most Aboriginal people are now based in towns that are geographically remote from Country, particularly significant places and islands in Sea Country, exacerbating these impacts. As witnessed in other Indigenous cultures globally, this physical and cultural disconnect can result in a loss of stewardship of nature as young people have less opportunity to experience Country and cultural practices (Soga and Gaston 2018; Hayward et al. 2022; Strand et al. 2022).

The Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) manages land and marine reserves across Western Australia under the Conservation and Land Management Act 1984 (CALM Act), including functions to design, implement and evaluate management plans of vested land and waters. Since 2011, changes to legislation have enabled Aboriginal groups to enter formal joint management of the State’s conservation estate to ‘protect and conserve the value of the land to the culture and heritage of Aboriginal persons’ (CALM Act). As of 2023, 24% of the State’s conservation reserve system is under joint management, including marine parks and marine management areas (Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions 2023a). By establishing joint management, Aboriginal Traditional Custodians are empowered through consultation within the design of management plans, conservation co-design (‘two-way science’ through the sharing of traditional and western knowledge) and active management of Country. The cultivation of partnerships and pathways, through Junior Ranger and trainee programs, for young Aboriginal people is a priority of DBCA and its conservation programs. Not only will these actions nourish generational investment in the protection of Country, but also contributes to addressing the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal communities by improving Aboriginal Peoples’ connection to Country, self-determination and leadership, and Indigenous beliefs and knowledge (Lowitja Institute 2020).

Marine turtles are a highly referenced key natural value across 19 management plans legislated under the CALM Act, which guide the research and monitoring needs of Western Australia’s conservation estates. Turtles are also important cultural species to Aboriginal Peoples in Western Australia, demonstrated by over 1218 turtle motifs recorded across Murujuga rock art in the Dampier Peninsula in the Pilbara (De Koning and McDonald 2023). With all six turtle species classified as Threatened on the State’s Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act) and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), they are considered a priority species for conservation within and outside of CALM Act conservation estate. The flatback turtle (Natator depressus), which nests across the Pilbara (‘North West Shelf’) and Kimberley regions of Western Australia, is listed as Vulnerable under the BC Act and EPBC Act and is endemic to the Australian coast. Management of flatback turtles in the Kimberley spans multiple Traditional Custodian estates and Indigenous protected areas (IPAs), with traditional ecological knowledge and Aboriginal rangers playing a significant role in the species’ conservation in this region (Tucker et al. 2021). The capacity for marine co-management in the Pilbara is still developing, with flatback nesting beaches located within several National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) areas but no IPAs yet established (The Enduring Pilbara 2024).

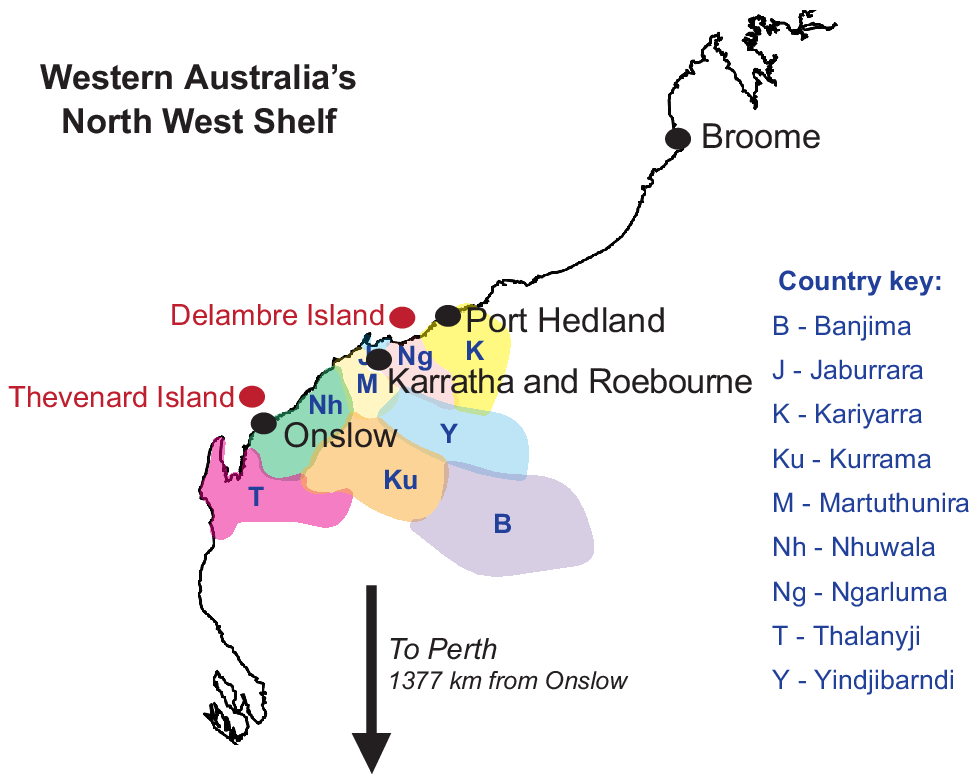

North West Shelf Flatback Turtle Conservation Program (NWSFTCP) and West Pilbara Turtle Program (WPTP) of the DBCA conduct conservation and monitoring of flatback turtle populations across the Pilbara’s North West Shelf, including Thalanyji, Nhuwala, Ngarluma, Jaburrara and Kariyarra Country. Funding for these programs is decadal, which provides opportunities for meaningful long-term partnerships and positive outcomes in communities. Working in cooperation with local Aboriginal Corporations and education organisations, the programs prioritise collaborating with local communities and Traditional Custodians on beaches nearby the towns of Karratha and Roebourne and remote islands on Sea Country in the Pilbara, providing conservation employment opportunities and engaging children, adolescents, and their families in flatback turtle fieldwork (Box 1, Fig. B1). Empowering a new generation of local environmental custodians who are inspired to engage in marine conservation, joint management and governance is essential for enabling the long-term action needed to address some of the ocean challenges in the Pilbara, and Australia more broadly, and conserve long-lived wildlife such as flatback turtles (Cranston et al. 2022; Strand et al. 2022).

| Box 1. |

| The West Pilbara Turtle Program annually monitors three beaches close to the towns of Karratha and Roebourne in Ngarluma Country; Bells Beach, Boat Beach and Cleaverville. |

| The North West Shelf Flatback Turtle Conservation Program operates annual turtle monitoring at two Pilbara nesting beaches; Thevenard Island in Thalanyji and Nhuwala Country is located 22 km off the coast of Onslow, and Delambre Island in Ngarluma Country is located in the Dampier Archipelago, 40 km from Karratha. |

Fig. B1. Locations of major towns and Thevenard and Delambre islands off the Pilbara coast, and the identification of Traditional Custodian Country for language groups that the NWSFTCP and WPTP currently work with (modified from AIATSIS.gov.au).  |

Young people on Country

To engage children and young adolescents in conservation, the NWSFTCP and WPTP collaborate with schools and organisations with high proportions of Aboriginal students on Sea Country that is local to the major monitoring sites of the program. By co-designing programs with the schools and community, students aged 8–14 years old experience Country with positive role models from both scientific and cultural backgrounds, engaging in ‘two-way science’ that connects the Western Australian Science Curriculum to Aboriginal knowledges (Department of Education 2022). Each year, classroom activities at schools are coupled with contextualised curriculum-linked lessons, beach walks, clean-ups, nocturnal marine turtle nesting observations, community events and remote island field trips to connect students to authentic and sensory experiences on Country. For all students, these experiences are critical to reducing the ‘adolescent dip’ that results in a disconnect with nature (Olsson and Gericke 2016; Keith et al. 2021). The program also contributes to ‘closing the gap’ for Aboriginal young people’s health, wellbeing, and education through the development of place-based curricula that emphasise opportunities to pursue future pathways for co-managing Country in the Pilbara (Fordham and Schwab 2012; Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2024).

Three case studies of engaging young people on Country through collaborations among schools, community organisations and marine turtle monitoring with the NWSFTCP and WPTP across the Pilbara are presented below.

Case study 1: community on Country – Waalitj Foundation

The Waalitj Foundation is a national organisation that delivers programs designed and developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to their communities (see https://wf.org.au/about/, accessed 25 October 2023). In the small Pilbara town of Onslow, the program focuses on providing education and health support to families. The Onslow Waalitj Foundation manager Suzanne Wilson acts as a conduit between allied services, external organisations and local families, and is a role model for youth in the community.

Prior to 2019, the NWSFTCP had been attempting to establish relationships with the Traditional Custodians in Onslow but were finding engagement and a consistent point of communication challenging. On meeting with Waalitj Foundation representatives, it was identified that the NWSFTCP could offer opportunities and funding that would support Waalitj Foundation’s vision to bring families together from different Traditional Custodian groups (Thalanyji, Banjima, Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Martu) to share knowledge and nourishing experiences on Sea Country that they are rarely able to access. This partnership would create a consistent community contact for the NWSFTCP from which to explore engagement opportunities and the development of future pathways for Aboriginal youth into conservation in the Onslow area.

Beginning in the summer of 2019, the families of Onslow Waalitj Foundation have taken annual trips to Thevenard Island during the flatback turtle nesting and hatching season. The families include grandparents, parents and children aged 6–14 years old from Onslow and the Bindi Bindi community of Wiluna, a remote inland community located in Martu Country in the Pilbara–Goldfields region.

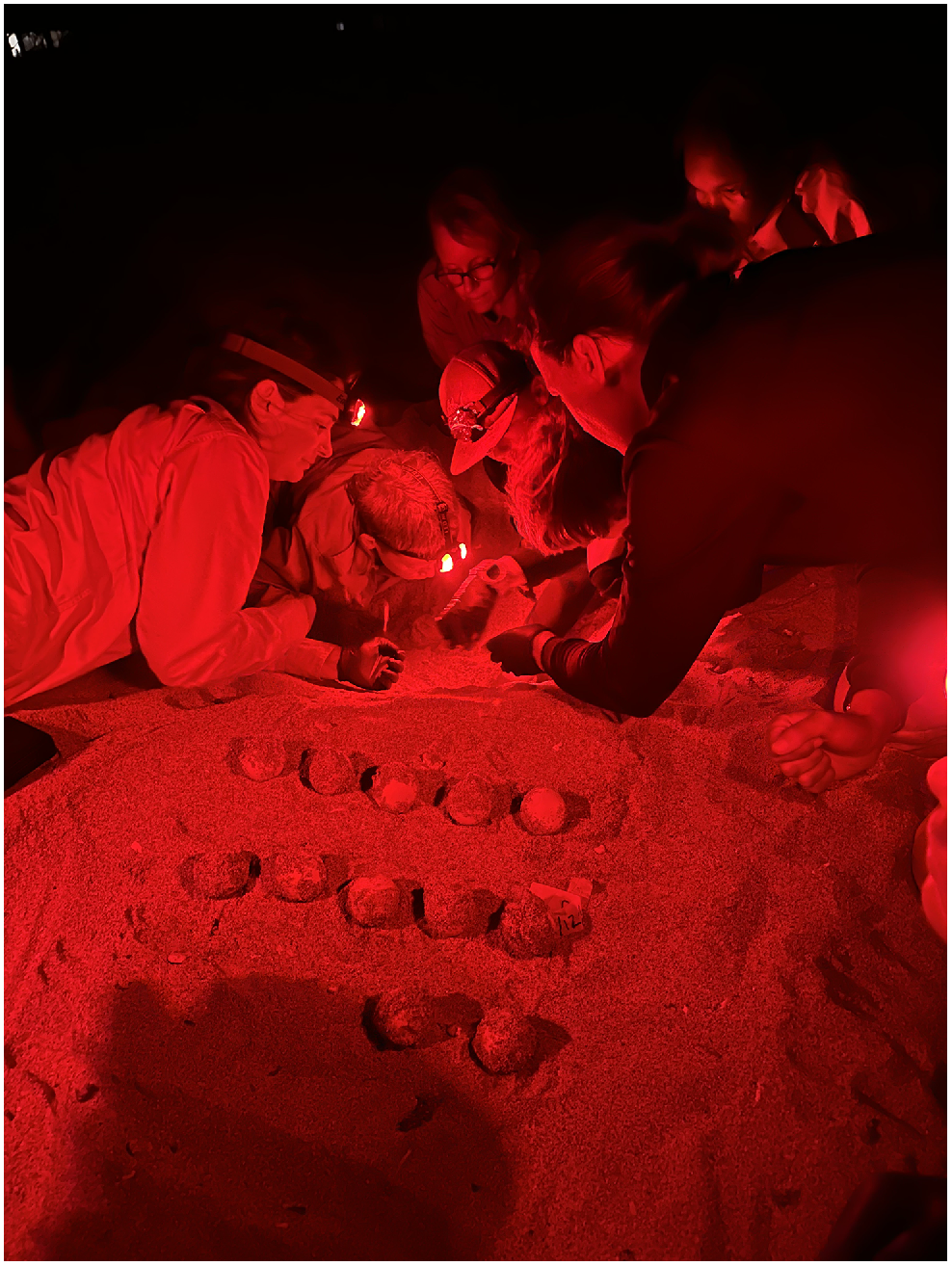

The NWSFTCP researchers and the families share knowledge about marine turtle biology and ecology, with the families joining researchers for monitoring in the evenings as the flatback turtles come up to nest and lay their eggs, and later, when hatchlings emerge (Box 2, Fig. B2). During the day, the families enjoy their time telling stories, fishing, playing and exploring the island and beaches with the Waalitj mentors. Observing the families building connections to each other and Country, away from social challenges on the mainland and their everyday lives, is an aspect of the partnership that managers of Onslow Waalitj Foundation identify as particularly significant.

For school-aged young people, the opportunity to engage with Country and nature alongside positive community role models and their families is an important aspect of fostering community leadership in Onslow into the future. With most students disengaging from education in mid- to upper-secondary years, empowering them through experiential learning on Country provides powerful incentive for their continued engagement in formal and community learning. Some students, who are now in Year 7 at Onslow School, have travelled to Thevenard Island with their families since the inception of the partnership and will be participating both with the school and with their families again this year. One student said of their experience, ‘I loved staying out at the islands and being on the beach watching a turtle lay its eggs’, whereas others talked of how much fun they have with their friends, family and experiencing encounters with turtles for the first time.

The NWSFTCP and Waalitj Foundation aim to co-design career development and pathway opportunities for Aboriginal young people in Onslow. At present, there are limited opportunities for students and parents to identify how to access careers in conservation even if they exhibit interest after the Thevenard Island experience. With the Thalanyji Ranger Program in its infancy, the NWSFTCP will provide support and expertise to upskill local rangers and explore partnering with other established Traditional Custodian ranger groups in the Pilbara to provide mentorship and opportunities to Onslow youth in the meantime. The NWSFTCP has also begun establishing more regular community sessions to present opportunities and news about Sea Country conservation in and around Onslow, to maintain relationships and interest within the community.

Case study 2: young adolescents on Country – Onslow School

Onslow School is located in the town of Onslow and has been operating for over 50 years. With a population consisting of 21% Aboriginal residents, ~40% of Onslow School students are from the Thalanyji, Yindjibarndi and Banjima language groups. As the only school in the town, it is an integral part of the community, and strong links exist among the school, staff, families and the wider community. The school accommodates students from kindergarten through to Year 12, with teaching and learning programs conducted in accordance with the Western Australian curriculum. Learning programs are designed to be locally relevant and to equip learners with the knowledge, skills and values to contribute to society and access opportunities in life.

In previous years, Onslow School hosted a Bush Rangers Cadets WA unit, a statewide voluntary program run as a collaboration of the DBCA, Department of Communities and Department of Education. Bush Rangers WA is a program that supports secondary school-aged youth to engage in personal development training, while developing conservation skills and knowledge through their involvement in practical nature conservation projects (Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions 2023b). This was a natural synergy with the work of the NWSFTCP, who approached the school in 2017 with an invitation to join the turtle-monitoring expedition on Thevenard Island.

Since 2017, the annual engagement of Onslow School with the NWSFTCP monitoring program has evolved. Being unable to maintain the Bush Rangers WA program because of staffing challenges, the school transitioned from supporting a Bush Rangers camp to hosting a camp that invites all Year 7 and Year 8 students to participate each year. The turtle-monitoring camp supports the school’s vision to give students the opportunity to enhance their local environmental knowledge and understanding, participate in service learning, work as a team, and experience new career pathways with positive role models (Box 3, Fig. B3).

Students who have participated in the turtle monitoring return as ambassadors for Thevenard Island and the work of DBCA and have been inspired to pursue conservation pathways. A Year 7 Aboriginal student who participated in 2022 said that this was the first time they had visited Thevenard Island and interacted with turtles, which made them feel more connected to Sea Country and nature. They have spoken with their Nan, auntie and sisters about the experience, and want to work on Country in conservation but are not sure about the specific pathways available. Developing pathway opportunities in collaboration with the Waalitj Foundation and local Aboriginal Corporations are next steps to ensure that these students have direction and can achieve their goals in conservation. For Onslow School, the partnership with the NWSFTCP has improved the community perceptions of education in Onslow and student engagement. The visiting NWSFTCP staff provide consistent expertise and experiential learning experiences that the students otherwise do not receive through distance education lessons. The program also highlights the relevance of STEM education to their local area, at a time when students are typically selecting away from STEM subjects (Department of Industry, Science and Resources 2024). Students look forward to the turtle-monitoring program as a ‘rite of passage’ in their first 2 years of secondary school, and it is a ‘selling point’ that the small school can offer local families who are considering boarding school or leaving town when students reach secondary school age.

Strengthening the partnership through more regular engagement and ‘two-way science’ co-design is a priority for both Onslow School and the NWSFTCP. This work has begun through the co-creation of lessons and education resources with the primary science specialist and Aboriginal and Islander Education Officer (AIEO) of the school and the education officer of the NWSFTCP, linking the science curriculum to marine turtle contexts and traditional ecological knowledge. Further development of ‘two-way science’ projects is a focus for the future, with the aim that students exposed to marine turtle traditional and western knowledge throughout primary school will be able to meaningfully apply their understanding during the Years 7 and 8 turtle monitoring camp, increase their environmental advocacy, and inspire young people to pursue future conservation and science pathways.

Case study 3: adolescents on Country – Roebourne District High School

Roebourne (Yirramagardu) is Western Australia’s oldest surviving town in the state’s north-west and is located 40 km east of Karratha in the Pilbara. Roebourne is a hub town in the Pilbara, where several displaced language groups have found a home. With a population consisting of primarily Aboriginal residents, 99% of Roebourne District High School (RDHS) students are from the Ngarluma (Traditional Custodians), and inland Yindjibarndi and Banyjima language groups.

RDHS experiences school-attendance challenges, particularly for secondary schooling years (Years 7–12). To increase wellbeing and engagement of students, the 2021–2023 vision of the school was to ‘deliver high quality educational experiences that build our students into confident and capable members of the wider community’ (Roebourne District High School 2021, p. 3). The school has engaged in the Big Picture Education model since 2018, which prepares students for opportunities beyond school by engaging them in real-world learning and internships, alongside learning that is based on students’ individual interests and needs.

On being approached by staff from the NWSFTCP and WPTP with the opportunity to engage in turtle monitoring on local Wickham beaches (from 2018) and Delambre Island (from 2020) on Ngarluma Country, there was a strong interest and desire from the RDHS students to participate. An essential success factor identified for this collaboration was the co-design of pre-excursion learning with RDHS staff to ensure that it developed interest and motivation for students to be actively involved in the project (Box 4, Fig. B4).

Since 2020, the NWSFTCP, WPTP and RDHS staff have undertaken several planning sessions each year to co-design lessons that are interactive and engaging for young learners and align with the school’s approach to learning. This has resulted in ‘information exploration’ lessons that communicate important information about marine turtles and their conservation and provide students with a hands-on understanding of what is involved in the marine turtle monitoring program on Delambre Island and potential future conservation pathways. Participation in the turtle monitoring excursion as a ‘tagalong experience’ has been student centered, with students being required to indicate an interest and willingness to commit to the research experience after engaging in the information exploration lessons.

A significant challenge experienced during the planning of the Delambre Island turtle monitoring excursion has been gaining the systemic approvals required to take school children by vessel to a remote camping location. However, by consulting the Department of Education and working together to ensure processes and documentation met the Department’s standards, the NWSFTCP and RDHS staff have been able to gain approval and provide a safe experience to students.

After the success of the turtle monitoring excursion in 2020, the RDHS students and staff were eager to continue the collaborative project with the NWSFTCTP. Students who have participated in 2020 and 2021 have reflected on their hands-on experiences with turtles (‘inserting the PIT tag was mad [good] because they were so powerful’), engaging with science and discussing their on-Country learning on community radio in 2021.

Despite several challenges establishing the on-Country experience, the on-going relationship between DBCA and RDHS is an important outcome. The NWSFTCP and WPTP team will continue working with RDHS to align the experiences at Wickham and Delambre Island with school priorities, provide turtle monitoring opportunities for interested students, support the school staff’s ‘local champions’, and build post-school science and conservation pathways for students for the long-term. Gaining the support of the local Ngarluma Aboriginal Corporation Elders and ranger groups, so that students can continue work experience on Country with Aboriginal role models, is essential for the long-term success of this project, and the NWSFTCP and WPTP teams will be focusing on these relationships for the near future.

Conclusions

Addressing ocean issues, such as the conservation of biodiversity and threatened species such as marine turtles, is a challenge and long-term endeavor that the young people of today will inherit. It is more important than ever to ensure that children and adolescents remain connected to nature through meaningful and authentic experiences, so that they retain pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors into adulthood and are equipped to actively address these issues. For Aboriginal young people, on-Country nature experiences with community role models are of utmost importance for the future of Sea Country conservation, for self-determination and for the nourishment of passionate, informed community leaders.

Through meaningfully involving local communities, Traditional Custodians and their young people in conservation projects, programs such as DBCA’s WPTP and NWSFTCP, demonstrate the significant impact that scientific programs can have at environmental, social, and cultural levels. The case studies outlined have relied strongly on relationship building within and between communities and the programs, the dedicated work of individuals (‘local champions’) within each group, and the framing of youth and community engagement through ‘two-way science’ and education as core priorities of the conservation programs. Improvements can still be made in terms of engaging with Elders and traditional knowledge holders in the design and implementation of the projects on Country, thereby ‘decolonising’ the approach to support intergenerational knowledge transfer and relational learning (Poelina et al. 2023).

To ensure the sustainability of community engagement programs such as this, it is vital to ensure that ongoing and mutually supportive relationships are nourished through regular communication and presence. This requires the engagement of dedicated education and outreach personnel to conservation programs, with the ability to be flexible and patient to foster relationships with communities and trial new approaches. Discussions continue as to how best to measure the success of these programs for conservation, education and social outcomes, with dynamic success metrics of varying time scales being required.

Ultimately, engagement pathways must be available to young people who are inspired to pursue conservation. Pathways for young people with aspirations in conservation science, joint management and governance are built on strong partnerships among government agencies, schools, Aboriginal Corporations, universities, and not-for-profit organisations. Enabling opportunities for Aboriginal young people to connect with Country and pursue self-determined pathways where they are empowered to use Traditional Ecological Knowledge is critical for protecting Sea Country into the future, and for improving the health and wellbeing of future Aboriginal generations. The ongoing co-development of such programs and partnerships is a priority for the NWSFTCP and WPTP, and should be a priority for all research and monitoring programs operating across Australia.

The greater the opportunity for all young people and communities in Australia to connect with nature and have authentic experiences with their community on Country, the closer we are to solving complex ocean and ecosystem challenges into the future.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable because no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Declaration of funding

This work was conducted with the consent of participants and guardians and adhered to the ‘National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research’ and ‘AITSIS Code of Ethics’. Throughout the work, no data or intellectual property has been collected from any individuals involved, other than the quotations in this article. This work is supported by funding from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attraction’s North West Shelf Flatback Turtle Conservation Program, Waalitj Foundation and Rio Tinto.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land and sea country where this work has been conducted – the Whadjuk Noongar, Thalanyji, Nhuwala and Ngarluma Peoples. We pay our respects to their Elders; past, present and emerging. The authors acknowledge the work of the West Pilbara Turtle Program Committee: Tim Hunt (DBCA), Suzie Glac (DBCA), Kat Dyball (DBCA), Swapna Chakkupurakkal (Rio Tinto), Ryan Donnavan (Rio Tinto) and Braydon Graham (Rio Tinto) and the staff of and contributors to the North West Shelf Flatback Turtle Conservation Program including Hannah Hampson (DBCA), Tony Tucker (DBCA), and the Advisory Committee. We acknowledge the staff at Onslow School and Roebourne District High School and the Department of Education for their commitment to providing students authentic and meaningful learning experiences and pathways; the staff of the Roebourne Police and Community Youth Center at Roebourne including Samantha Cornthwaite and Vish Sharma for enabling Wickham Beach visits for the Roebourne community, and the Waalitj Foundation including Josie Janz-Dawson, Troy Cook and Dale Kickett for their ongoing commitment to providing the community with cultural and conservation experiences on Country.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021) Regional population. (ABS) Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/2021 [Verified 9 October 2023]

Australian Law Reform Commission (2010) Legal definitions of Aboriginality. (ALRC) Available at https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/essentially-yours-the-protection-of-human-genetic-information-in-australia-alrc-report-96/36-kinship-and-identity/legal-definitions-of-aboriginality/ [Verified 27 May 2024]

Barber M, Jackson S (2011) Water and Indigenous people in the Pilbara, Western Australia: a preliminary study. (CSIRO Water for a Healthy Country Flagship) Available at &https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/download?pid=legacy:386&dsid=DS1 [Verified 22 September 2023]

Barbière J (2023) Ocean decade alliance. (UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission) Available at https://oceandecade.org/ocean-decade-alliance/ [Verified 11 October 2023]

Brodie Rudolph T, Ruckelshaus M, Swilling M, Allison EH, Österblom H, Gelcich S, Mbatha P (2020) A transition to sustainable ocean governance. Nature Communications 11, 3600.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chawla L, Cushing DF (2007) Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research 13(4), 437-452.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cheng JC-H, Monroe MC (2012) Connection to nature: children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environment and Behavior 44(1), 31-49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Corlett RT (2015) The Anthropocene concept in ecology and conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 30(1), 36-41.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cranston KA, Wong WY, Knowlton S, Bennett C, Rivadeneira S (2022) Five psychological principles of codesigning conservation with (not for) communities. Zoo Biology 41(5), 409-417.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (2023a) Bush Rangers WA. (Government of Western Australia) Available at https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/get-involved/education/bush-rangers [Verified 25 October 2023]

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (2023b) Joint Management. (Government of Western Australia) Available at https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/management/aboriginal-engagement/joint-management [Verified 10 October 2023]

Department of Education (2022) Two-way science initiative overview. (Government of Western Australia) Available at https://myresources.education.wa.edu.au/programs/two-way-science-initiative [Verified 30 May 2024]

Department of Industry, Science and Resources (2024) Pathway to Diversity in STEM final recommendations report. Available at https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/pathway-diversity-stem-review-final-recommendations-report [Verified 23 November 2024]

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (2024) Closing the Gap targets and outcomes. (Commonwealth of Australia) Available at https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement/targets [Verified 17 May 2024]

Fordham A, Schwab RG (2012) Indigenous youth engagement in natural resource management in Australia and North America: a review. (Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University) Available at https://dspace-prod.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/38d11cf6-9a51-4bad-afd6-9ce9c23b24aa/content [Verified 27 May 2024]

Gregory K, Paterson A (2015) Commemorating the colonial Pilbara: beyond memorials into difficult history. National Identities 17(2), 137-153.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayward MW, Meyer NFV, Balkenhol N, Beranek CT, Bugir CK, Bushell KV, Callen A, Dickman AJ, Griffin AS, Haswell PM, Howell LG, Jordan CA, Klop-Toker K, Moll RJ, Montgomery RA, Mudumba T, Ospiova L, Periquet S, Reyna-Hurtado R, Ripple WJ, Sales LP, Weise FJ, Witt RR, Lindsey PA (2022) Intergenerational inequity: stealing the joy and benefits of nature from our children. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10, 830830.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hughes J, Rogerson M, Barton J, Bragg R (2019) Age and connection to nature: when is engagement critical? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17(5), 265-269.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Keith RJ, Given LM, Martin JM, Hochuli DF (2021) Urban children’s connections to nature and environmental behaviors differ with age and gender. PLoS ONE 16(7), e0255421.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lowitja Institute (2020) Close the Gap Report 2020. Available at https://www.lowitja.org.au/resource/close-the-gap-report-2020/ [Verified 23 November 2024]

Olsson D, Gericke N (2016) The adolescent dip in students’ sustainability consciousness: implications for education for sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education 47(1), 35-51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Poelina A, Paradies Y, Wooltorton S, Guimond L, Jackson-Barrett L, Blaise M (2023) Indigenous philosophy in environmental education. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 39(3), 269-278.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reconciliation Australia (2021) Let’s talk … languages. (Reconciliation Australia) Available at https://www.reconciliation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ra-letstalk-factsheet-languages_final.pdf [Verified 27 May]

Richardson M, Hunt A, Hinds J, Bragg R, Fido D, Petronzi D, Barbett L, Clitherow T, White M (2019) A measure of nature connectedness for children and adults: validation, performance, and insights. Sustainability 11(12), 3250.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rist P, Rassip W, Yunupingu D, Wearne J, Gould J, Dulfer-Hyams M, Bock E, Smyth D (2019) Indigenous protected areas in Sea Country: Indigenous-driven collaborative marine protected areas in Australia. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 29(S2), 138-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Roebourne District High School (2021) Roebourne District High School: Business plan 2021–2023. (RDHS) Available at http://www.roebournedhs.wa.edu.au/Profiles/roebournedhs/Assets/ClientData/Images/2022/Additional_School_Information/Business_Plan_2021-2023.pdf [Verified 17 October 2023]

Soga M, Gaston KJ (2018) Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16(4), 222-230.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Strand M, Rivers N, Snow B (2022) Reimagining ocean stewardship: arts-based methods to ‘Hear’ and ‘See’ Indigenous and local knowledge in ocean management. Frontiers in Marine Science 9, 886632.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

The Enduring Pilbara (2024) Opportunities on Aboriginal-managed land. Available at https://enduringpilbara.org.au/opportunities-on-aboriginal-managed-land/#:~:text=Australia%20has%2078%20IPAs%2C%20making%20up%20about%2046%25,as%20limited%20federal%20funding%20for%20the%20IPA%20program [Verified 27 May 2024]

Tucker AD, Pendoley KL, Murray K, Loewenthal G, Barber C, Denda J, Lincoln G, Mathews D, Oades D, Whiting SD, Rangers MG, Rangers B, Rangers WG, Rangers D, Rangers M, Rangers BJ, Rangers NN, Rangers Y, Rangers K, Rangers N, Rangers N (2021) Regional Ranking of marine turtle nesting in remote Western Australia by integrating traditional ecological knowledge and remote sensing. Remote Sensing 13(22), 4696.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre (2024) Pilbara Aboriginal History. (Wangka Maya) Available at https://www.wangkamaya.org.au/history/01-introduction [Verified 22 September 2023]

Wells NM, Lekies KS (2006) Nature and the life course: pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Children, Youth and Environments 16(1), 1-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Footnotes

1 ‘Aboriginal’ is defined, for the purpose of this article, as a person who self-identifies as a descendent of the inhabitants of Australia prior to European colonisation (Australian Law Reform Commission 2010).

2 ‘Sea Country’ is capitalised because it is considered a proper noun. It is used by Aboriginal Australians to refer to any environment associated with the sea or coastal areas of which there is significant cultural connection, resulting from the inundation of ancestral coastal land after the last glacial period (Rist et al. 2019).