Fistula formation after usage of pessary for pelvic organ prolapse: a case series

Hnin Yee Kyaw A * , Hannah G. Krause A B C and Judith T. W. Goh A B DA

B

C

D

Abstract

A case series of five women with genital tract fistula formation as a complication of vaginal pessary use for pelvic organ prolapse is presented, along with treatment provided and patient outcomes. Review on this topic reveals specific pessary types more commonly associated with severe complications. Recommendations to reduce such complications include careful patient selection, regular follow-up with physical examination, vigilance to enable early recognition of such complications and offering alternative treatment options. Surgical repair of genital tract fistula with concurrent prolapse surgery is feasible and effective.

Keywords: fistula surgery, gynaecological surgery, gynaecologic surgical procedures, pelvic organ prolapse, pessaries, rectovaginal fistula, vesicovaginal fistula.

Introduction

About 40% of women will experience pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in their lifetime.1 Treatment for POP ranges from non-surgical to surgical options. Vaginal pessaries are devices inserted into the vagina to support the prolapse and remain a mainstay of non-surgical treatment. There is a reported 90% efficacy for vaginal pessary treatment of POP, with a 75% satisfaction rate amongst users attributed to improved vaginal and sexual symptoms, quality of life, and mental health.2 Common complications of vaginal pessary usage include abnormal vaginal discharge/vaginitis, discomfort, erosion and bleeding. More serious complications can include fistula formation and its sequelae. Estimation on incidence of pessary complications is difficult as the true rate of pessary use is unknown, and no standardised database for collection of complications exists.

Case series

All patients presented below have provided informed consent for the publication of this case series. Patient details are de-identified for confidentiality, and treatment provided was standard care for the fistula surgeons.

Case 1

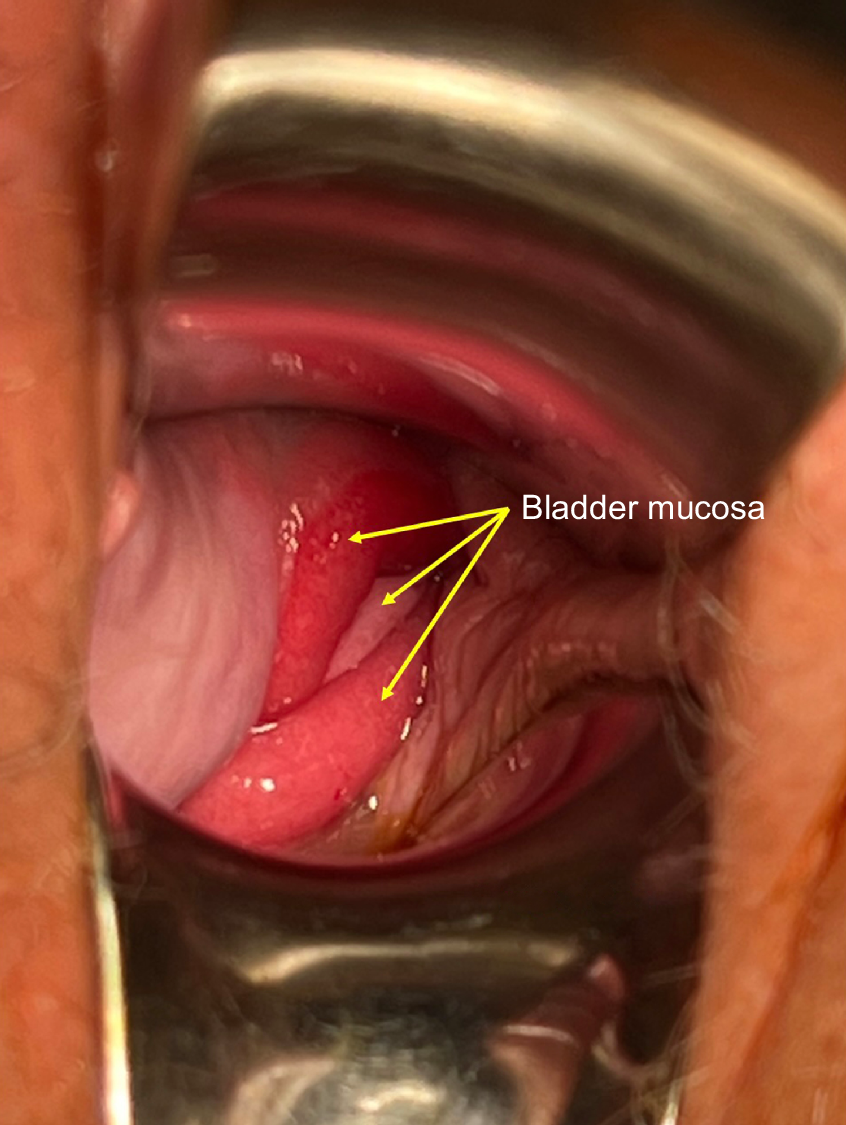

An 89-year-old woman who presented with urinary incontinence despite having an indwelling catheter in situ was found to have a neglected shelf pessary inserted 5 years earlier. She suffered from cognitive dysfunction. On examination, a 3 cm vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) adjacent to the cervix was found with oedematous surrounding tissue, prolapsed bladder mucosa and the right ureteric orifice protruding through the fistula (Fig. 1, Goh classification type 1biii).3 The upper vagina and cervix were ulcerated. Vaginal prolapse surgery was undertaken concurrently with vaginal VVF repair.

Case 2

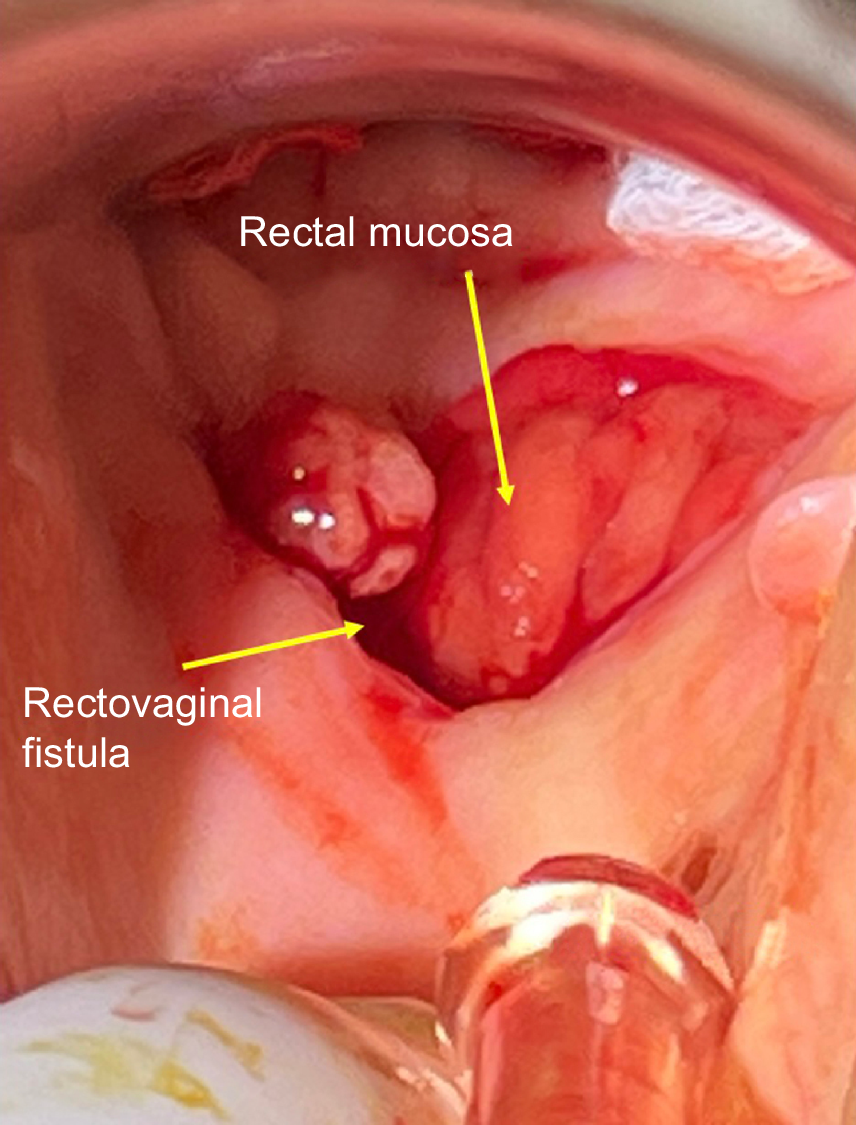

A 94-year-old woman presented with faeces in the vagina. She had been using a size 8 Gellhorn pessary for POP, with regular reviews by a gynaecologist. On examination, a 4 cm rectovaginal fistula (RVF) was found 1 cm below the cervix (Fig. 2, Goh classification type 1ci).3 The fistula was repaired vaginally without bowel diversion, and a concomitant vaginal repair with sacrospinous fixation was performed.

Case 3

An 81-year-old woman with previous hysterectomy presented with constant urine leakage 6 months following insertion of a cube pessary. On examination, she was found to have a 1 cm vault VVF (Goh classification type 1ai).3 She underwent a VVF repair with concomitant vaginal repair and sacrospinous fixation.

Case 4

A 74-year-old woman presented with faecal incontinence per vaginum and had a cube pessary in-situ for 3 months. She had no previous surgeries. On examination, she was found to have a 4 cm RVF located 3–4 cm above the introitus (Goh classification type 2ci).3 This RVF was repaired with concomitant vaginal repair and sacrospinous fixation, without bowel diversion.

Case 5

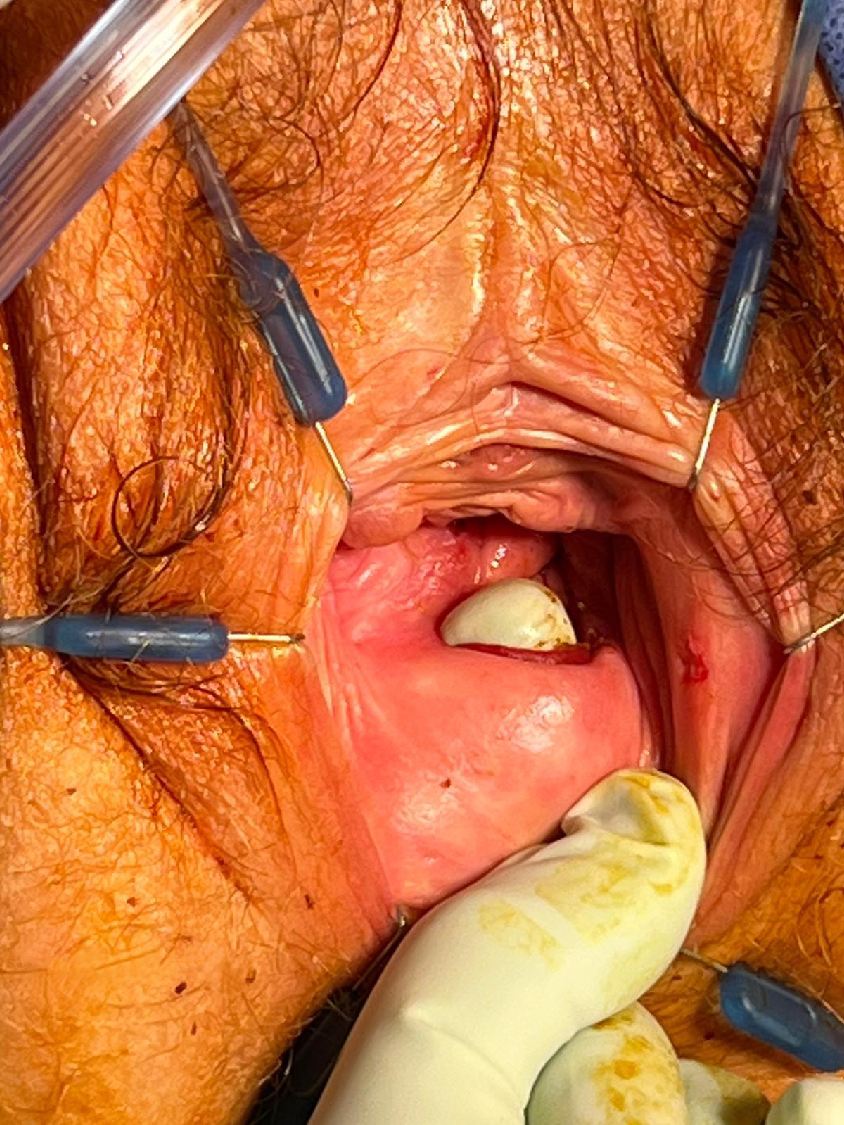

An 84-year-old woman presented with passing flatus per vaginum along with findings of faeces on a malpositioned shelf pessary after long term use of a shelf pessary. She previously attended regular monthly pessary follow-ups. On examination, she was found to have a midline 2 cm RVF located 3 cm from the introitus (Fig. 3, Goh classification type 2bi).3 This RVF was repaired with concomitant vaginal repair and sacrospinous fixation, without bowel diversion.

Discussion

This case series highlights five cases of severe complication after pessary insertion, which is a commonly used non-surgical treatment option for POP. A systematic review of complications secondary to pessary use found an association with pessary shape and material.4 Issues such as vaginal discharge/vaginitis, erosion, and bleeding occurred across all design types and materials. Serious complications such as VVF were most often linked to Gellhorn and shelf designs, whereas RVF was more commonly linked to rubber or PVC pessaries.

All but one patient in this case series was more than 80 years old (median age: 84.4 years). The different pessaries encountered were shelf pessary (n = 2), cube pessary (n = 2), and Gellhorn pessary (n = 1). Only one patient had a neglected pessary, with the other four having attended regular follow-ups. It should be noted that there is no standard definition of a ‘neglected pessary’ or ‘routine follow-up’.5 The American Urogynecologic Society–Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (AUGS-SUNA) Joint Clinical Consensus Statement recommended that an outpatient clinic follow-up is arranged within 4 weeks after initial pessary fitting.6 Following this, maintenance pessary review is recommended every 3–6 months. There was no evidence that shorter visit intervals reduced the frequency of serious complications, despite the increased cost to both patient and the healthcare system. In patients who can self-manage their pessaries, the maintenance pessary review appointments can be scheduled annually.

Commonly stated contraindications to usage of vaginal pessaries for POP are vaginitis or an active pelvic infection, allergies to type of product being used, and a noncompliant patient where follow-up is not assured.7–9 Cognitive dysfunction was a factor at the time of diagnosis for one patient in this case series; however, it is not known whether this decline developed after the initial decision for pessary treatment. It would be prudent for the treating healthcare worker to note when an elderly patient with a pessary fails to attend follow-up reviews, with efforts made to remove the pessary and seek alternative treatment if the patient’s new circumstances make regular follow-up impossible.

There are several systems of classifying genital tract fistulae.3,10,11 A concerted effort to communicate fistula findings would help clinicians audit results and facilitate future research into treatment methods and outcomes in a standardised manner. Beardmore-Gray et al. reported that an increasing size of fistula was shown to decrease surgical success (Goh classification size a [<1.5 cm] compared to size b/c [1.5–3 cm/>3 cm]).12 A decrease in continence rates post-surgical repair was also found with increasing Goh classification type, with type 1 fistula demonstrating a 100% continence rate as opposed to only 75% in type 4.

All five patients in our case series had Goh classification type 1 or 2 fistulae with sizes varying from a to c, and all underwent successful primary fistula repair.3 The surgeons involved in their care are certified urogynecologists and fistula surgeons. As is standard practice in this series, all patients undergoing RVF repair were given an enema on admission prior to surgery, and no bowel diversion was performed. Postoperatively, standard management included fluid diet on day 1, then normal diet commencing on day 2. Uterine sparing vaginal prolapse surgery was performed with repair of RVF to avoid potential peritoneal contamination. For VVF repairs, as standard practice the women had indwelling catheters for 14 days postoperatively, followed by removal of the catheter after a negative dye test and immediate trial of void. All patients were given prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics and a vaginal pack for 2 days. All patients were reviewed at 6 weeks and 2–3 months post-surgery by the operating surgeons, with no recurrence of their fistula or POP.

In conclusion, vaginal pessary for treatment of POP is generally safe and effective, and in well-selected patients can provide satisfactory outcomes. Follow-up by a trained clinician is vital, ensuring pessary removal and careful inspection of vaginal tissue health on each visit including a speculum examination. Time intervals between each follow-up appointment should be based on patient characteristics and type of pessary used. Patients should be educated on abnormal symptoms and empowered to request earlier appointments as necessary. New symptoms such as urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence, abnormal discharge, pain, or vaginal bleeding should not be ignored. All care providers including next-of-kin for the patient should be informed of the presence of a foreign body in circumstances where cognitive function is a concern, or alternative management such as surgical repair should be sought if indicated. Consideration of vaginal oestrogen therapy should be made for patients who are postmenopausal. Caution should be practiced in prescription of space-occupying pessaries which may increase the risk of fistula complication due to increased pressure and ‘suction’ on vaginal walls. Concomitant vaginal prolapse surgery is feasible with fistula repair and should be considered to reduce the need for future pessary use.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

1 Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, Stewart F, Dembinsky M, Sobiesuo P, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for managing pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 11(11): CD004010.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Zeiger BB, da Silva Carramão S, Del Roy CA, da Silva TT, Hwang SM, Auge APF. Vaginal pessary in advanced pelvic organ prolapse: impact on quality of life. Int Urogynecol J 2022; 33(7): 2013-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Goh JTW. A new classification for female genital tract fistula. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 44(6): 502-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Abdulaziz M, Stothers L, Lazare D, Macnab A. An integrative review and severity classification of complications related to pessary use in the treatment of female pelvic organ prolapse. Can Urol Assoc J 2015; 9(5-6): E400-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Vaginal pessary use and management for pelvic organ prolapse. Urogynecology 2023; 29(1): 5-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Rockefeller NF. Treating POP and SUI with pessaries. Contemp OB/GYN 2020; 65(3): 8-12.

| Google Scholar |

8 Jones KA, Harmanli O. Pessary use in pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2010; 3(1): 3-9.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Lewicky-Gaupp C. Contemporary use of the pessary 2010. Available at https://www.glowm.com/section-view/heading/Contemporary%20Use%20of%20the%20Pessary/item/25#

10 Hamlin RHJ, Nicholson EC. Reconstruction of urethra totally destroyed in labour. Br Med J 1969; 2(5650): 147-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Waaldijk K. Surgical classification of obstetric fistulas. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1995; 49(2): 161-3.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Beardmore-Gray A, Pakzad M, Hamid R, Ockrim J, Greenwell T. Does the Goh classification predict the outcome of vesico-vaginal fistula repair in the developed world? Int Urogynecol J 2017; 28: 937-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |