Scientific Visualization in Astronomy: Towards the Petascale Astronomy Era

Amr Hassan A B and Christopher J. Fluke AA Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Vic. 3122, Australia

B Corresponding author. Email: ahassan@astro.swin.edu.au

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 28(2) 150-170 https://doi.org/10.1071/AS10031

Submitted: 03 September 10 Accepted: 25 February 11 Published: 20 June 2011

Journal Compilation © Astronomical Society of Australia 2011

Abstract

Astronomy is entering a new era of discovery, coincident with the establishment of new facilities for observation and simulation that will routinely generate petabytes of data. While an increasing reliance on automated data analysis is anticipated, a critical role will remain for visualization-based knowledge discovery. We have investigated scientific visualization applications in astronomy through an examination of the literature published during the last two decades. We identify the two most active fields for progress — visualization of large-N particle data and spectral data cubes — discuss open areas of research, and introduce a mapping between astronomical sources of data and data representations used in general-purpose visualization tools. We discuss contributions using high-performance computing architectures (e.g. distributed processing and GPUs), collaborative astronomy visualization, the use of workflow systems to store metadata about visualization parameters, and the use of advanced interaction devices. We examine a number of issues that may be limiting the spread of scientific visualization research in astronomy and identify six grand challenges for scientific visualization research in the Petascale Astronomy Era.

Keywords: methods: data analysis — techniques: miscellaneous

1 Introduction

Astronomy is a data-intensive science. Petabytes1 of observational data is already in stored archives (Szalay and Gray 2001; Brunner et al. 2002), even before facilities such as the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA; Brown et al. (2004)), the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST; Ivezic et al. (2008)), LOFAR (Röttgering 2003), SkyMapper (Keller et al. 2007), the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP; Johnston et al. (2008)), the Karoo Array Telescope (MeerKAT; Booth et al. (2009)), and ultimately the Square Kilometre Array itself, reach full operational status. Cosmological simulations with 1010 particles (e.g. Springel (2005); Klypin et al. (2010)) are also producing many-terabyte datasets, and the highest-resolution simulation codes executed on the next generation of petaflop/s supercomputers will result in further petabytes of data. The Petascale Astronomy Era is a natural outcome of current and future major observatories and supercomputer facilities.

Astronomy sits alongside fields such as high-energy physics and bioinformatics in terms of the data volumes that are available to its practitioners. Such data volumes pose significant challenges for data analysis, storage and access, leading to the development of a fourth data-intensive (or eScience) paradigm for science (Szalay and Gray 2006; Bell et al. 2009). Much work will be required to find effective solutions for knowledge discovery in the Petascale Astronomy Era, with a likely emphasis on automated analysis and data-mining processes (Ball and Brunner 2009; Borne 2009; Pesenson et al. 2010). However, a critical step in understanding, interpreting, and verifying the outcome of automated approaches requires human intervention. This is most easily achieved by simply looking at the data: the human visual system has powerful pattern-recognition capabilities that computers are far from being able to replicate.

The use of diagrams, maps and graphs has a long history in astronomy2 to explain concepts, aid understanding, present results, and to engage the public. However, there is more to visualization than just making pretty pictures. Data visualization is a fundamental, enabling technology for knowledge discovery, and an important research field in its own right.

The broader field of astronomy visualization encompasses topics such as optical and radio imaging, presentation of simulation results, multi-dimensional exploration of catalogues, and public outreach visuals. Aspects of visualization are utilized in the various stages of astronomical research — from the planning stage, through the observing process or running of a simulation, quality control, qualitative knowledge discovery and quantitative analysis.3 Indeed, much of astronomy deals with the process of making and displaying two-dimensional (2D) images (e.g. from CCDs) or graphs which are suitable for publication in books, journals, conference presentations and in education (see Fluke et al. (2009) for alternatives).

An important sub-field of visualization is scientific visualization: the process of turning (numerical) data with dimensionality N ≥ 3, usually with an inherent geometrical structure, into images that can be inspected by eye. At its conception in the 1980s (McCormick et al. 1987; Frenkel 1988; DeFanti et al. 1989), scientific visualization was envisaged as an interactive process, with an emphasis on understanding and analysis of data (including qualitative, comparative and quantitative stages), not just presentation (Wright 2005). Research in this field includes techniques for displaying data (e.g. through the use of surface rendering, volume rendering and streamlines), efficient implementations of display algorithms for increasingly complex data and data structures (including both data dimensionality and dataset size) while retaining interactivity, and effective use of high-performance computing for tasks such as parallel rendering and computational steering (where interaction with a simulation occurs during processing, and helps to drive the direction of the next stage of processing). We refer the interested reader to the general introductions by Gallagher (1995), Johnson and Hansen (2004), and Schroeder et al. (2006).

There is a very subtle distinction between scientific visualization and the closely related field of information visualization (Spence 2001). The latter deals with the presentation and understanding of multi-dimensional data, where the search for relationships between data points is the motivation for investigation. The following example attempts to highlight the difference: a map of the locations of normal elliptical galaxies with a colour scheme or symbols relating to mean surface brightness, effective surface brightness and central velocity disperson (so that the emphasis is on the spatial arrangment) is a scientific visualization; a three-dimensional plot of these last three quantitites demonstrating how they form the fundamental plane (Djorgovski and Davis 1987) is an information visualization. Similarly, a three-dimensional (3D) plot of the (x, y, z) locations of particles from an N-body simulation, where no colour coding is used to present additional numerical properties, is information visualization (essentially a 3D scatter plot), but colouring particles by local density or temperature, or the use of a surface or volume rendering technique to identify large-scale structures, is scientific visualization. We make use of this distinction in order to help identify research work that is relevant for our overview, and for brevity use ‘visualization’ hereafter to mean three-dimensional scientific visualization.

As a multidisciplinary field, scientific visualization has been used with great success in medical imaging, molecular modelling, engineering (e.g. computational fluid dynamics), architecture, and astronomy. Scientific visualization of astronomical data includes observational data generated over a variety of wavelengths (optical, radio, X-ray, etc.) and data from computer simulations. Visualization of observational data poses some specific challenges in terms of the data volume, dynamic range, (often low) signal-to-noise ratio, incomplete or sparse sampling, and astronomy-specific coordinate systems. For simulations, challenges include the number of particles, mesh resolution, and range of length and time scales. While none of these issues are unique to astronomy, effective astrophysical visualization taken as a whole requires its own unique solutions.

One of the first systematic astronomy visualization trials was undertaken by Gitta Domik, Kristina Mickus-Miceli, and collaborators at the University of Colorado (Mickus et al. (1990a, 1990b); Domik (1992); Domik and Mickus-Miceli (1992); Brugel et al. (1993)). They developed a prototype application named the Scientific Toolkit for Astrophysical Research (STAR) using IDL on top of X-Windows. Their main goals were to offer visualization tools that were driven by the needs of astronomers, and that would integrate with existing data analysis tools. STAR’s main functionality included display of one- and two-dimensional datasets, perspective projection, pseudo-colouring, interactive colour-coding techniques, volumetric data displays, and data slicing. STAR was introduced as a prototype to prove the feasibility of the user interface and visualization techniques proposed in their report.

Norris (1994) presented a blueprint for visualization research in astronomy, highlighting the suitability of 3D visualization for providing an intuitive understanding that was missing when using 2D approaches (e.g. data slicing, where individual channels are examined separately or played back as a movie, requiring the viewer to remember what was seen in earlier channels). Visualization techniques could enable features of the data to be seen that would otherwise have remained unnoticed, such as low signal-to-noise structures extending over multiple channels. Norris (1994) noted the importance of visualization in communicating results qualitatively, but identified quantitative visualization as the missing ingredient that would allow true interactive hypothesis testing — an essential part of the scientific process. While still relevant today, several key aspects — most notably a wider uptake of 3D visualization by astronomers — have yet to be fully realised.

1.1 Scope and Purpose

We consider the development, advancement and application of scientific visualization techniques in astronomy over the last two decades, coincident with the lifetime of scientific visualization as a field of inquiry in its own right. To our knowledge, there have been no previous attempts to examine the status of scientific visualization in astronomy. The Masters thesis by Palomino (2003) discusses visualization strategies for several numerical datasets from astronomical simulations; Leech and Jenness (2005) surveyed visualization software available for radio and sub-millimetre data; Dubinski (2008) provided an introduction to particle visualization as a companion to a brief history of N-body methods; Kapferer and Riser (2008) considered software and hardware visualization requirements for numerical simulations; Li et al. (2008) described strategies for dealing with multi-wavelength data; and Fluke et al. (2009) summarised some basic elements of cosmological visualization for observational and simulation data.

It is not our intent to provide a comprehensive account of all research outcomes that have made use of scientific visualization tools or approaches (see Brodbeck et al. (1998), Hultquist et al. (2003), or the growing scientific output from the AstroMed project, Borkin et al. (2008), Goodman et al. (2009), and Arce et al. (2010) for representative examples), but to investigate how scientific visualization in astronomy has advanced over the last two decades. In particular, we do not consider geographical-style 3D visualization from planetary missions, or data from solar physics (see Ireland and Young (2009), and articles therein, or Aschwanden (2010) for a complementary review of the latter field). We aim to provide an overview for researchers who wish to understand the state of scientific visualization in astronomy, with an emphasis on simulation and spectral cube data, aiming to motivate future work in this field. We assert that many current astronomy visualization approaches and applications are incompatible with the Petascale Astronomy Era, and much work is required to ensure that astronomers have the tools they need for knowledge discovery over the next decade and beyond.

The remainder of this paper is set out as follows. In section 2 we present an overview of progress in scientific visualization in astronomy, from projects in the early 1990s until the present. We pay special attention to two important classes of data: large-N particle systems (section 2.3), and spectral data cubes (section 2.4). We consider other research areas including distributed (section 2.5) and collaborative visualization (section 2.6), image display (section 2.7), workflow (section 2.8), and public outreach visuals (section 2.9). In section 3, we demonstrate how the nature of astronomical data impacts the choice of visualization software, highlighting some of the advantages and disadvantages of using general visualization packages instead of custom astronomy code. In section 4, we discuss some of the challenges that astrophysical visualization must overcome in order to be useful and usable, and identify six grand challenges for scientific visualization research in the Petascale Astronomy Era. Finally, we present our concluding remarks in section 5.

For an article on visualization, it may seem surprising that so few images have been included. Our preference is for the reader to view the original, published versions, appearing as their author(s) intended, rather than attempting to replicate them here. Any omission of significant work or software related to scientific visualization in astronomy is wholly the responsibility of the authors.

2 Scientific Visualization in Astronomy

2.1 Visualization Techniques

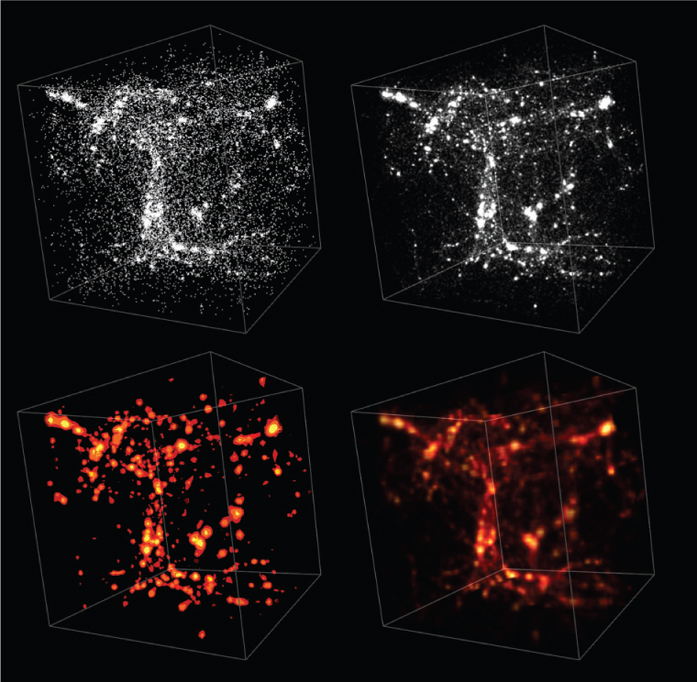

As a starting point for exploring advancements in scientific visualization in astronomy, we introduce the most common techniques for presenting three-dimensional scalar data in astronomy: points, splats, isosurfaces and volume rendering.4 Figure 1 shows how the same dataset, in this case a single snapshot from a cosmological simulation, appears when rendered using the four techniques.

Plotting points (top left) as fixed-width pixels is often the most straightforward representation; however, this approach is limited by the available resolution (or pixel density) of the display. Splatting (top right) uses small textures, often with a Gaussian intensity profile, to replace point-like objects. Splats are billboards, in the sense that they always point towards the virtual camera regardless of the orientation of the scene, and scale better with distance than do pixels. Combining splats on the graphics card gives an effect like volume rendering, but without the calculation overhead of ray-tracing.

An isosurface (bottom left) or isodensity surface is a three-dimensional equivalent of contouring. Common methods for calculating an isosurface from a dataset include marching cubes (Lorensen and Cline 1987; Montani et al. 1994), marching tetrahedra (Bloomenthal 1994), multiresolution isosurface extraction (Gerstner and Pajarola 2000), and surface wavefront propagation (Wood et al. 2000). Isosurfaces are usually used to search for correlation between different scalar variables, but are less useful to give a global picture of the dataset. Volume rendering (bottom right) attempts to provide a global view of the dataset, particularly useful to render both the external surfaces and the interior 3D structures with the ability to display weak or fuzzy surfaces. Volume rendering can be performed using ray-tracing or using the graphics card to combine a series of (semi-)transparent texture maps (e.g. Cabral et al. (1994); this approach was used for Figure 1).

2.2 The Nature of Astronomical Data

The nature of data has an impact on the choice of visualization technique, and hence software. One way to look at astronomical data (Brunner et al. 2002) is to consider the origin or physical source:

-

Imaging data: two-dimensional within a narrow wavelength range at a particular epoch.

-

Catalogues: secondary parameters determined from processing of image data (coordinates, fluxes, sizes, etc.).

-

Spectroscopic data and associated products: this includes one-dimensional spectra and 3D spectral data cubes, data on distances obtained from redshifts, chemical composition of sources, etc.

-

Studies in the time domain: including observations of moving objects, variable and transient sources which require multiple observations at different epochs, and synoptic surveys.

-

Numerical simulations from theory: which can include properties such as spatial position, velocity, mass, density, temperature, and particle type. These properties may also be presented with an explicit time dependence through the use of ‘snapshot’ outputs.

An alternative classification (see Gallagher (1995)) is based on how the data is representated programmatically, i.e. how it is stored and organized in memory or on disk:

-

Scattered points: data is comprised of a set of point locations (x, y, z) and associated data attributes (e.g. density, pressure, and temperature).

-

Structured grid: data values are specified on a regular three-dimensional grid, with grid cells aligned with the Cartesian axes.

-

Unstructured grid: data values are specified on corners of a 2D/3D shape element with an explicitly defined connectivity.

-

Adaptive grid: data values are specified on a multi-resolution structured grid. A coarse grid is used to cover the entire computational domain combined with superimposed sub-grids to provide higher resolution for regions of interest (e.g. where particle density is highest).

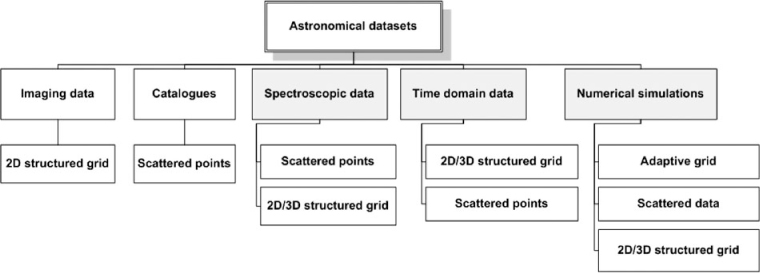

Figure 2 demonstrates each of these representations. This second classification is more familiar to practioners of scientific data visualization, and is one that helps guide the choice of visualization techniques in a way that is somewhat independent of a particular scientific domain. Figure 3 demonstrates, in broad terms, how the astronomically-motivated data categories can be mapped into the data representation schema. Unstructured grids are rarely used in astronomy because they are usually generated from finite element analysis or domain decomposition methods, which are not widely used in astronomy (see Springel (2010) for an example of unstructured grid usage).

With regard to 3D scientific visualization, we are primarily interested in spectroscopic data, time-domain data, and numerical simulations, but there may be a need to overlay images (e.g. image slicing), or secondary catalogue data (e.g. for comparisons between multiwavelength data). Based on the astronomical data category, the majority of visualization papers that we identified related to either N-body and other large-scale particle simulations or spectral data cubes. We now summarize the main developments in each of these two areas. In particular, we focus on the implementation trends, as this provides a useful starting point for future work in this field, and occurences of the visualization techniques outlined in Section 2.1. We do not attempt to provide specific technical details of each visualization solution, as some approaches are now outdated due to improvements in graphics hardware — most notably through the appearance of low-cost, massively parallel graphics procesing units (GPUs).

2.3 Large-N Particle Simulations

For a science where direct experimentation is challenging, numerical simulations provide astronomers with a link between observations and theory. Continued growth in processing power, new architectures and improved algorithms have all enabled simulations to increase in resolution and accuracy. Most astronomy simulations use of one of three main data representations (see Figure 3):

-

Multi-dimensional scattered data, such as the GADGET-2 (Springel 2005) file format. Here, each data point is characterised by a set of spatial coordinates, with additional scalar and vector properties. This can be mapped to a regular scattered data visualization problem.

-

3D/2D structured grid, where the point data is distributed over a regularly-spaced mesh with a predefined resolution using smoothing techniques such as cloud-in-cell (Hockney and Eastwood 1988). This data representation may cause a loss in fine details at scales below the mesh size (Hopf et al. 2004).

-

Adaptive/multi-resolution grid, where the point data is distributed over an adaptive mesh with a variable resolution. This is often the best data representation to cover a wide spatial and temporal domain with a minimal data size (Kähler et al. 2002). However, the implementation and handling of boundary conditions between scales can be challenging.

Table 1 summarizes contributions dedicated to the N-particle visualization problem with a classification based on the dataset representation type, the implementation trend, and the main visualization techniques used. It is noteworthy here that Palomino (2003), Staff et al. (2004), Biddiscombe et al. (2007), and Kapferer and Riser (2008) presented the usage of vector plots as one of the visualization techniques. Although it is not commonly used to represent vector quantities from simulations in astronomy, vector visualization is a very useful technique as has been demonstrated in other fields, especially computational fluid dynamics. However, interpreting the physical meaning of vector fields is a higher-level cognitive task than identifying structures through the use of surface or volume rendering.

Visualizing N-particle data is a problem common to many scientific fields (e.g. point-based surface representations for 3D geometry processing5), and this has been an area for active research over the last two decades. Such datasets are most amenable to the use of general-purpose scientific visualization tools/libraries, although there is still a tendency for astronomers to develop their own solutions. In the astronomical literature, we identify three main approaches to implementation.

The first approach is to use an existing general-purpose tool without modification (Palomino 2003; Navratil et al. 2007; Kapferer and Riser 2008); however, a data preprocessing step is usually required to convert the data into a suitable representation before the visualization is performed. Palomino (2003) used IDL to visualize 2D/3D numerical simulations of magneto-hydrodynamic clouds in the interstellar medium, stellar jets from variable sources, neutron star–black hole coalescence, and accretion disks around a black hole. Navratil et al. (2007) used Paraview and Partiview to render a time-dependent dataset of the first stars and their impact on cosmic history. Kapferer and Riser (2008) presented the usage of IFrIT, MayaVi data visualize, Paraview, and VisIT with a discussion of the visual quality aspects, generating interactive 3D movies, real-time vector-field visualization, and high-resolution display techniques. They also showed the usage of the VisTrials workflow system for saving visualization metadata.

The second approach was to modify or extend existing general-purpose tools (Becciani et al. 2000, 2001, 2010; Gheller et al. 2002, 2003; Kähler et al. 2002; Amati et al. 2003; Ahrens et al. 2006). Becciani et al. (2000, 2001), Gheller et al. (2002, 2003), and Amati et al. (2003) describe the development of the AstroMD tool (a tool developed within the European Cosmo.Lab project6). Its user interface was built based on Tool Command Language (TCL/TK)7 while its visualization functionality uses The Visualization ToolKit (VTK).8 It includes visualization capabilities such as: isosurfaces, volume rendering, point picker, and sphere sampler. This work was continued by Comparato et al. (2007) and Becciani et al. (2010) through the VisIVO project. VisIVO was based on the Multimod application framework (MAF). Kähler and Hege (2002), Kähler et al. (2002), and Kähler et al. (2003, 2006) introduced an AMIRA9 extension to render adaptive mesh refinement datasets. Their work was initiated within the framework of a television production for the Discovery Channel for rendering for the first stars in the universe.

The final approach is to develop a custom system or library from scratch. From Table 1, we can say that it is quite a popular choice (Ostriker and Norman 1997; Norman et al. 1999; Kähler et al. 2007; Linsen et al. 2008; Dubinski 2008; Szalay et al. 2008; Nakasone et al. 2009; Jin et al. 2010). Ostriker and Norman (1997) and Norman et al. (1999) described the work done within the Computational Cosmology Observatory (CCO), which acts as an environment analogous to an astronomical observatory. Its implementation included: a specialized I/O library to handle Hierarchical Data Format (HDF) files, a desktop visualization tool, virtual-reality navigation and animation techniques, and Web-based workbenches for handling and exploring adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) data (Plewa et al. 2005).

Kähler et al. (2006) and Kähler et al. (2007) used a GPU-assisted ray-casting algorithm to provide a high-quality volume rendering of AMR datasets. They avoided re-sampling the point's data onto a structured grid by directly encoding the point data in a GPU-octree data structure. Linsen et al. (2008) adopted a visualization approach based on isosurface extraction from multi-field particle volume data. They projected the N-dimensional data into 3D star coordinates to help the user select a cluster of features. Based on the segmentation property induced by the cluster membership, a surface is extracted from the volume data. Dubinski (2008) presented the MYRIAD library. MYRIAD has been integrated with two different parallel N-body codes (PARTREE10 and GOTPM11).

Szalay et al. (2008) implemented a system that uses hierarchical level-of-details (LOD) for particle-like cosmological simulations, in order to display accurate results without loading in the full dataset. They were able to achieve a framerate of 10 frames per second with a desktop workstation and NVidia GeForce 8800 graphics card.

The last noteworthy work in this direction is that done by Dolag et al. (2008) and Jin et al. (2010). They introduced a tool to render point-like data directly in the GADGET-2 format. They used ray tracing to render in a fast and effective way the different families of point-like data. The same algorithm was enhanced to use GPUs with Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA)12 and distributed clusters using Message Passing Interface (MPI).13

There is no clear choice regarding which approach should be favoured, as there is a strong dependence on the visualization objectives and target. Most of the users of the first and the second approaches aim to minimize the development cost and to use existing, tested, and open-source packages with minimal or no modification. On the other hand, the researchers using the third approach aim to enable the use of available advanced or specialized hardware infrastructure (e.g. the Grid environment (Becciani et al. 2010), or GPUs (Kähler et al. 2006) and (Jin et al. 2010)); produce better or faster visualization results through customizing an existing visualization technique (Hopf et al. (2004); Dolag et al. (2008); Szalay et al. (2008)); or utilize new platforms, such as web platforms or virtual environments, and provide users with better interfaces or support collaborative interaction (Nakasone et al. (2009) and Becciani et al. (2010)).

Visualization approaches and software have needed to keep pace with improvements in simulation techniques and resolution (which can include an increase in N or the number of grid cells). Indeed, visualizing ‘large-N’ datasets, relative to the era of implementation, was addressed by most of the works (Ostriker and Norman (1997); Norman et al. (1999); Welling and Derthick (2000); Kähler et al. (2006, 2007); Szalay et al. (2008); Jin et al. (2010); Becciani et al. (2010)). Attempts to solve this problem included the use of grid computing or a distributed cluster as the computing infrastructure (Ostriker and Norman 1997; Norman et al. 1999; Becciani et al. 2010; Jin et al. 2010); using GPUs as the computing infrastructure (Ahrens et al. 2006; Kähler et al. 2006; Biddiscombe et al. 2007; Kähler et al. 2007; Szalay et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2010), and see Hassan et al. (2010) for a solution using a distributed cluster with GPUs; and using the dataset characteristics or optimized data structure to provide a multi-resolution visualization solution (Hopf and Ertl 2003; Hopf et al. 2004).

Of all the applications of scientific visualization in astronomy that we have examined, N-particle data provides the closest match to, and hence may be the greatest beneficiary of advances in, the wider field of scientific visualization. Their particular use of scattered and grid data formats means that general purpose visualization packages (see Section 3) are more suitable for handling simulation data, the need to convert from custom astronomy data formats to required input formats notwithstanding. There may be some benefit in providing simple file conversion tools; otherwise, astronomers using simulation data may care to investigate alternative standard data representations (e.g. HDF5,14 VTK file format). While sharing some similarities with gridded simulation data, visualization of spectral data cubes presents some unique problems, which we now explore.

2.4 Spectral Data Cubes

A spectral data cube has two spatial dimensions (usually RA and Dec, or galactic longitude and latitude), one frequency or wavelength dimension, and a flux value.15 The frequency or wavelength dimension is often converted to a line-of-sight velocity using Doppler-shift relationships. Spectral data cubes are more common in radio astronomy. However, with improvements in integral field units (IFUs) and similar instrumentation, optical/IR astronomy is seeing a growth in the collection and use of spectral cubes.

Spectral data cubes are characterized by a lack of well-defined surfaces, low signal-to-noise data values combined with a high dynamic data range, and the use of special coordinate systems that do not always match well with the equal-unit 3D spatial coordinates of other disciplines. This limits the use of existing general-purpose scientific visualization tools, particular in comparison with simulation data. It is still very common for astronomers to rely on 2D techniques, such as data slicing or projected moment maps, as the primary method for visualizing data. These approaches can be achieved using packages like SAOImage DS9,16 or some modules of Karma Karma (Gooch 1996). However, with terabyte-scale data cubes from near-term facilities telescopes like ALMA, ASKAP, and MeerKAT, slicing techniques may not be feasible (e.g. it would take ~30 minutes to step through a ~16,000-channel ASKAP cube at 10 frames/sec, assuming that there was software capable of supporting this approach), and the complex kinematics of an unresolved pair of merging galaxies, for example, may not be fully captured using a 2D moment map.

Early work by Norris (1994), Gooch (1995a), and Oosterloo (1995) emphasised the opportunity for 3D visualization to aid in the processes of data analysis and knowledge discovery. Since then, three main techniques have been used to visualize spectral data cubes: isosurfacing, volume rendering, and (2D) data slicing. Volume rendering has dominated 3D spectral cube visualization in general due to its ability to give the user a global data perspective, despite the lack of well-defined surfaces within the observational data, and its improved capability of visualizing in the low signal-to-noise regime.

Table 2 shows the key publications relating to spectral data cube visualization. Several comments need to be made on the table:

-

The data source classification was based on the experimental data presented in each paper.

-

The implementation trend ‘Modify’ is used to describe the published work if it uses an external library or tool to perform/support the visualization. In some cases (e.g. Beeson et al. (2003)) the application may add a lot of customizations and code enhancement to effectively handle the astronomical datasets.

-

It is clear that there are fewer publications in this branch of research than in N-particle visualization.

-

As noted above, volume rendering is the key visualization technique and is supported by all the tools.

The implementation trends for spectral cube visualization are similar to those found for particle data:

-

Modify/extend an existing general-purpose visualization library (e.g. Domik (1992); Brugel et al. (1993); Plante et al. (1999); Beeson et al. (2003); Draper et al. (2008)).

-

The use of some visualization packages developed to serve the medical visualization domain such as Paraview, 3D slicer, and Osirix (Borkin et al. 2007).

-

Build a custom visualization library/application (Gooch 1996; Kähler et al. 2007; Li et al. 2008; Hassan et al. 2010).

Special attention has been given to VTK as a basis for modifications/extensions achieved via the first implementation trend (Plante et al. 1999; Draper et al. 2008). On the other hand, it is also possible to use some of the packages classified as N-particle visualization tools for spectral data. Although no explicit examples have been shown through their publications, most of the N-particle tools capable of handling structured grids can visualize spectral data cubes (e.g. Gheller et al. (2003); Amati et al. (2003); Becciani et al. (2010); Kähler et al. (2007)).

While the use of high-performance computing architecture and hardware play an important role in visualizing N-particle datasets, only Beeson et al. (2003), Li et al. (2008), and Hassan et al. (2010) use that approach to improve the rendering speed or to handle larger-than-memory spectral datasets.

We believe 3D spectral data cube visualization is still in its infancy. There is a need to move spectral data cubes visualization tools from tools for generating ‘pretty pictures’ into powerful tools for data analysis. Spectral data visualization tools should provide their users with: quantitative visualization capabilities, the ability to handle huge datasets exceeding single-machine processing capacity, accepted interactivity levels, and effective noise-suppression techniques. Also, offering powerful two-way integration with other data analysis and reduction tools will be key to facilitate the wider usage of such tools. We will further discuss these issues within Section 4.

We now turn our attention to other developments in scientific visualization that are not related to the data representation: distributed and remote visualization services, collaborative visualization, visualization workflows, and public outreach outcomes. With the exception of public outreach visualization, there has been much less research effort expended in these areas for astronomy, and consequently, their level of community up-take is somewhat lower than for the particle and spectral cube approaches we have examined.

2.5 Distributed/Remote Visualization

Desktop computers have a finite memory size, typically a few gigabytes, yet many datasets from observation and simulation are much larger than this (e.g. processed ASKAP data cubes will be over 1 terabyte). A solution to this problem lies in the use of distributed visualization, where a networked computing cluster shares the processing tasks.

A typical astronomer does not always have immediate access to sufficient computational power or data-storage capacity to deal effectively with such large datasets. Moreover, effective and efficient implementation of software to deal with large datasets requires a higher level of computing knowledge relating to the choice and use of appropriate data structures, techniques for scheduling, and so on. Remote visualization therefore presents an opportunity to provide the wider astronomy community with a visualization service with potentially lower cost, less administrative effort, and a reduced need to transfer data. At the same time it presents a cost-effective way to further utilize existing expensive computational infrastructure. This philosophy was the main motivation for the Virtual Observatory (VO) concept of sharing datasets, and providing astronomers with data-analysis and visualization software as a service (see Quinn et al. (2004) and Williams and De Young (2009) for details). Rather than requiring local hardware, a user requests a visualization of a dataset from a remote host — the outcome of the visualization, usually an image, is returned to the user. Along with the time taken to produce images, such a system has an overhead in terms of the interaction speed and the network speed.

The issue of providing 3D visualization and computational infrastructure as a service was addressed by Plante et al. (1999), Murphy et al. (2006), and Becciani et al. (2010). All of them agreed on using the web as the main service platform. Plante et al. (1999) built a custom Virtual Reality Modeling Language (VRML)17 viewer using Java3D to render the output of a VTK-based server. The custom VRML viewer enables them to provide additional interactivity services such as a 3D cursor, the ability to select subregions, and the production of 2D JPEG snapshots of the visualization output. The same methodology was used by Beeson et al. (2004) to visualize data from catalogue streamed in XML format, but with a ready-made browser plugin to render VRML output. Murphy et al. (2006) describe an image-display remote visualization service (RVS)18 through a set of VO tools for the storage, processing and visualization of Australia Telescope Compact Array data. The RVS server accepts Flexible Image Transport System (FITS)19 images and provides a 2D visualization using an Astronomical Information Processing System (AIPS++)20 back end.

The last and probably one of the most complete systems is VisIVO web21 (Becciani et al. 2010). The system uses web 2.0 technology for user interaction, while the output is generated as static images, with a semi-interactive control of dataset orientation and movie generation. It is a simple way to implement such functionality, but is perhaps not as intuitive as the interaction provided through custom web controls or environments such as Java3D.

The usage of distributed processing to enable astronomers to handle larger-than-memory datasets was addressed by Beeson et al. (2003), Jin et al. (2010), and Hassan et al. (2010). Beeson et al. (2003) extended the shear warp volume-rendering algorithm (Lacroute and Levoy 1994) with a distributed implementation. Demonstrated using both spectral-line data cubes and N-body datasets, their technique relies on distributing the volume data among the participating computing nodes and then using the associative ‘over’ operator to yield a final image. Their code was based on Virtual Reality Volume Rendering (VIRVO) code.22

Jin et al. (2010) developed a custom ray-tracing code to render pointlike data in a fast and effective way. They exploit the use of multi-core architecture using OpenMP (Dolag et al. 2008), distributed memory architecture using MPI, and GPUs using the CUDA development toolkit. Their technique was demonstrated using N-body datasets only. Hassan et al. (2010) used a distributed GPU cluster to enable ray-casting volume rendering of datasets of up to 26 Gbytes at frame rates better than 5 frames/sec. Combining shared and distributed memory high-performance computing capabilities enabled them to handle larger-than-memory datasets at an acceptable frame rate with a lower number of nodes than Beeson et al. (2003).

2.6 Collaborative Visualization

Collaborative visualization enables multiple users to share a visualization experience. For this to be successul, the main requirements are high-speed networks and effective communication protocols. Early work in this field was by Van Buren et al. (1995), who implemented the AstroVR Collaboratory environment for distributed users to share in the analysis of FITS images. Communication between users was via audio, video, or typed text. The AstroVR approach was motivated by early client–server, multi-user networked games.23 Plante et al. (1999) described collaborative support in the NCSA Horizon Image Data Browser (Version 2.0) via NCSA Habanero.24 Collaborators were able to join a Habanero collaborative application (hablet)25 session following an e-mail invitation, with interaction via the GUI visible to all participants.

Both Djorgovski et al. (2009) and Nakasone et al. (2009) consider the use of virtual environments based on the Second Life26 framework developed by Linden Labs. Launched in 2003, Second Life is an online, multi-user, virtual world application with support for real-time interaction, creation and exploration of three-dimensional environments, and synchronous communication (including both text and voice). As of early 2010, Second Life had more than 16 million registered accounts, although only ~40,000 ‘residents’ are typically online at any one time. It is the collaborative experience that is of most interest to astronomers — geographically distributed users can interact simultaneously with a data visualization, with feedback on what the other participants are doing/seeing. The main drawback at present is the limited support for large astronomical datasets : the Second Life application imposes a limit of 15,000 objects, leaving Nakasone et al. (2009) to experiment with visualizing only 1024 particles from a stellar cluster simulation. Djorgovski et al. (2009) propose adapting OpenSim,27 an open-source implementation of Second Life, which may partly remove that restriction.

2.7 Image Display and Interaction

While not unique to scientific visualization, the use of advanced displays for presentation of, and interaction with, three-dimensional datasets is worthy of consideration. Advanced displays may include tiled or multi-display walls, stereoscopic environments ranging from flat-screens to immersive Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE)28-like environments, and domes (upright and tilted).

Early descriptions of the limitations of 2D displays for 3D astronomical data are in Fomalont (1982) and Rots (1986). Rots (1986) described the use of a mosaic of 2D slices, time-sequence animations, the creation of 3D solid surfaces (i.e. an isosurface at a given threshold level), and the possibilities offered by stereoscopic images and holograms! Fluke et al. (2006) considered a suite of advanced displays including multi-panel or tiled displays, digital domes, and stereoscopic projection, with descriptions of low-cost implementations of each display. Comprehensive overviews of stereoscopic and 3D display systems and technologies may be found in McAllister (2006) or Holliman et al. (2006).

One of the main challenges is the lack of native support for advanced displays from visualization software (Fluke et al. 2006). Most advanced displays require images in a different format to conventional displays (i.e. on a monitor or data projector). This includes fish-eye or other spherical projection for domes, and image pairs for stereoscopic displays. There is an overhead in producing such frames, which can have a negative impact on frame rates and hence usability. On the other hand, viewing data with an advanced display may yield additional insight. Apart from a few projects using CAVE-like environments, stereoscopic and dome display has mostly been reserved for public outreach visualization (see Section 2.9).

A related issue, which has yet to achieve a satisfactory resolution, is the choice of an appropriate 3D interaction device. Intuitive and easy real-time interaction with visualization output, including changing visualization parameters, camera position, and interactive dynamic data filtering (Shneiderman 1994), is vital to achieve the required visualization outcomes. This may also be one of the reasons why quantitative techniques in 3D have not advanced (Gooch 1995a, 1995b), as they require a device (e.g. for selection of objects or regions) that is as simple to use in 3D as the mouse is for interacting with 2D data.

Few astronomy publications have explictly addressed practical alternatives for interacting with astronomical data. Gooch (1995b) considered the 6-degrees-of-freedom Spaceball (Spatial Systems, Inc.) as an alternative to manipulate a 3D cursor within a 3D volume. The Spaceball was a low-cost version of the devices used in immersive environments, controlling additional functionality such as interactive slicing. Kähler and Hege (2002) and Kähler et al. (2002) used a voice- and gesture-controlled CAVE application to define a camera path following the interesting features.

2.8 Workflow

When dealing with a large amount of datasets, additional benefits may be achieved using workflow-driven applications. Selecting a certain visualization parameter is not usually a straightforward process: knowledge of the visualization algorithms and dataset characteristics are essential to achieve sensible visualization outcomes. Indeed, reproducing specific visualization results is challenging, particular when an interactive process has been used to control properties such as data limits, transparency, colour maps and orientation. Keeping metadata about the visualization process itself through an integrated workflow management system was addressed by Kapferer and Riser (2008). They discussed the usage of VisTrials29 as a scientific workflow management system that provides support for data exploration and visualization.

On the other hand, providing the user with visualization software that tightly integrates with simulation, data-analysis, or data-generation tools may facilitate the use of new visualization tools and techniques, remove the data conversion barrier, and provide better interoperability. Some published work (e.g. Dubinski (2008); Comparato et al. (2007)) discusses this concept, and different real-time data-sharing and integration protocols were introduced as a part of the VO initiative (e.g Taylor et al. (2006)).

Li et al. (2008) present a visualization workflow for multi-wavelength astronomical data. The importance of their work comes from the completeness of their proposed framework, which includes GPU-based data processing and new ways to visualize multi-wavelength astronomical data with volume visualizations (such as the ‘horseshoe’ model). They offer a collection of interactive exploration tools tailored for multi-wavelength datasets.

2.9 Public Outreach

Astronomy has a demonstrated history of engaging public interest in science — this has been achieved in large part by the appealing visuals that are routinely generated from telescopes and simulations. As professional astronomers, there is something special about being able to share the results of our research work with the public. It is easy for our passion to inspire audiences of all ages, from the youngest school students to adults. However, the techniques that we often use in collecting, understanding and exploring our datasets (histograms, scatter plots, error-bars, etc.) do not always make for visually appealing, or necessarily understandable, presentations. Public-outreach visuals are qualitative, or occasionally comparative, but rarely quantitative.

In some sense, public outreach use of scientific visualization techniques has exceeded that for science outcomes, with a number of advancements in astronomy visualization motivated by outreach or presentation goals. At times, the divide between an outreach visualization and one that is intended to help astronomers to gain deeper understanding of their models and observerations is very narrow. Cases in point are the highly realistic renderings of the Orion nebulae (Emmart et al. 2000), emission nebulae, and planetary nebulae (Magnor et al. 2004), which we describe below, and the previous discussion of AMR visualizations starting with Kähler et al. (2002) (section 2.3).

In 2000, within the SIGGRAPH 2000 electronic theatre, a team from the San Diego Supercomputing Center (SDSC) presented a volume-rendering video animation for the Orion nebula (Emmart et al. 2000). Nadeau et al. (2001) and Genetti (2002) described this work in more detail, including their use of a volume scene graph (Nadeau 2000). They reported a set of limitations in the available volume-rendering applications/libraries, including a lack of efficient parallel-perspective volume rendering, forcing them to build a customized parallel-perspective viewing model, and the need for high voxel resolution to capture all details over a wide range of length scales (from proplyds within the central region of the nebula, with a scale of 0.007 light years, to the outskirts of the nebula at 14.3 light years). Additionally, to achieve a sufficient level of photorealism with regards to the glowing gas in the nebula, existing treatment of transparency as the inverse of the opacity did not work — it was necessary to modify the modelling and rendering tools to allow independent values for transparency and opacity.

Realistic planetary nebula models were created using constrained inverse volume rendering by Magnor et al. (2004). As a purely emissive model (i.e. glowing gas), the fast, texture-based volume rendering technqiue of Cabral et al. (1994) was found to be an appropriate visualization solution. The goal of this work was to create realistic-looking planetary nebulae, enabling models to be fitted to three observed systems with bipolar symmetry. Magnor et al. (2005) implemented a solution to the more complex case of generating interactive volume renderings of 3D models with dust (e.g. reflection nebulae) by using GPU-based ray-casting. A scattering depth is assigned to each voxel of the nebulae, and these are accumulated along the view-dependent line-of-sight. The code was able to handle multiple illuminating stars along with multiple scattering events.

Computer techniques have greatly simplified the process of creating custom animations. Starting with segments like Where the Galaxies Are (Geller et al. 1992) using data from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) redshift surveys, the ‘galaxy distribution fly-through’ has become a standard way to visualize galaxy redshift survey data.

Public outreach visualization often requires the combination of disparate data sets and data types — and visualization packages. For example, the stereoscopic movie Cosmic Cookery (Holliman et al. 2006), used data from the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey (Colless et al. 2001), large-scale structure from the Millennium simulation (Springel et al. 2005), higher-resolution galaxy formation simulations, and conceptual animations to link between sequences. Packages used for this movie included Celestia,30 PartiView, 3DSMax, VolView by KitWare,31 and custom rendering software.

‘Solar Journey’, implemented in VRML and OpenGL, demonstrates components of the solar envirnoment as both an interactive environment and a short animated film (Hanson et al. 2002). Problems that needed to be solved included registration of multispectral datasets, texture-mapping of objects from Earth-based images, and difficulities with providing a completely accurate spatial model when true spatial information on some features was limited.

While opportunities for further public outreach using 3D visualization exist, the reality is that productions of this nature come at a cost. They are time-consuming to produce, which is not necessarily an incentive for researchers who are already time-poor. They usually require access to (sometimes expensive) commercial animation packages (e.g. Maya, Lightwave, 3DSMax) and experienced animators, neither of which can often be justified within research-only budgets. These same animation packages are not designed for the types of data that astronomers use, so there is a need for significant conversions of datasets to animation-friendly formats (e.g. FITS Liberator). Creating flight-paths can be a non-trivial process. Rendering, the process of creating individual frames that are then brought together to form a movie sequence, can take from minutes to hours per frame, and can require access to a supercomputer or dedicated render farm.

The challenge is to simplify the process of creating engaging visualisations that can also enhance research productivity. That is, visualisation tools that are not just designed for public presentations, but can also be used in the academic context for conference presentations, research publications, or department/personal web pages. Astronomers usually do not need (or want) pre-rendered computer animations. To analyze their data, real-time interactive solutions are much more valuable.

3 Visualization Software

While astronomers have written about their own visualization software, there is no summary of the variety of packages that are available. Leech and Jenness (2005) surveyed visualization software suitable for sub-millimetre spectral line data, considering user requirements such as FITS format, compatibility with astronomical coordinates, support for mosaicing, display of 2D slices and moment maps, and quantitative capabilities. 3D rendering functionality was considered ‘a plus’. They weighed up the pros and cons of AIPS++ (McMullin et al. 2004), the Starlink Software Collection (Draper et al. 2005) (specifically the

3.1 Custom Code

While there has been much effort to date in creating general-purpose visualization tools (such as Paraview,34 VisIT35 and AMIRA36), many of these existing software packages are not suitable for astronomy due to:

-

limitations with handling specific astronomy data formats (e.g. FITS or the GADGET-2 file format) which require a data format conversion process before using these tools (e.g fits2itk).37 This data-format conversion disables the direct real-time integration and may imply increase in the dataset size;

-

the need for conversion from astronomically meaningful units (RA, Dec, redshift) to general units (cm or mm in three dimensions), which often limits the user to exploring data in a qualitative form only (see

http://am.iic.harvard.edu/UsingSlicer for an example); -

the high dynamic-range, low signal-to-noise domain in which many observational projects work; and

-

the data volumes (billion-particle data generated for high-resolution cosmological simulations or many giga-voxels for high resolution spectral cubes).

These issues necessitate the creation of domain-specific applications and solving visualization problems that are unique to astronomy. However, utilizing existing visualization general-purpose libraries is a good starting point.

In Tables 3 and 4, we provide a list of libraries and packages aimed at supporting scientific visualization of astronomical data. This list does not make any claims on completeness or suitability of a package for a particular dataset. Web links were correct (and live) at the time of writing. VTK and OpenGL are the main workhorses for scientific visualization, providing the basis for many of the listed tools; however, as programming and development environments, they have a reasonably steep learning curve, and what may seem like simple tasks can take some time to code. The advantage of a pre-existing visualization package or library (either general-purpose or astronomy-focused) is that someone else has dealt with implementation issues, which should mean that you can get to a science outcome faster. The downside is that any pre-existing package may not be able to do exactly what you require it to do.

|

|

4 Discussion

In this review of scientific visualization in astronomy, we have attempted to provide an overview of the work that has been undertaken over the last two decades. A few key techniques from the broader discipline of scientific visualization have been adopted by astronomers, most notably the use of volume rendering and scattered-point representations, while others are rarely used (in particular, streamlines and vector visualization). Based on our assessment of the literature, we now consider some of the key challenges for wider adoption and research into relevant scientific visualization techniques for astronomy from the viewpoints of visualization researchers and astronomers.

4.1 Challenges for Visualization Researchers

Although the format of astronomy datasets may be familiar to people working in scientific visualization, astrophysical datasets have a set of special characteristics that may limit the usability of some more general visualization techniques despite them having a much wider user-base and higher level of technical support. These features can be summarized into the following points:

-

Lack of dominant efficient data representation. Within some astronomy sub-fields, there is no single dominant data representation. For example, N-body simulation data can exist in different data formats such as the GADGET-2 file format and custom ASCII or binary formats. Also, there is a lack of standard data representation for catalogues. Although the introduction of the VOTable format (proposed by the International Virtual Observatory Alliance) represents an attempt to unify data in internet-accessible format, it is not yet widely used. Not only does this raise interoperability issues but also makes the development of generic astronomy visualization packages either complex or incomplete. On the other hand, some current commonly used astronomy data representations (especially FITS) are more oriented toward data archiving than efficient data accessibility. This limits the application's ability (not only visualization applications) to provide users with fast data loading, disables the usage of out-of-core algorithms, and disables the usage of distributed data storage. An exception to this is the usage of NCSA hierarchical data form (HDF)38 which permits parallel input and output and enables distributed data storage (Ostriker and Norman 1997).

-

Different packages solve this problem by using a single data format for internal implementation and provide users with an importing functionality that converts existing commonly used data formats into the internal file format (e.g. Sanchez (2004); Sanchez et al. (2004); Kissler-Patig et al. (2004); Becciani et al. (2010)). This may not be an efficient solution for large datasets due to storage and processing requirements.

-

Low signal-to-noise ratio and high dynamic range. Data generated from radio or optical telescopes often combines a low signal-to-noise ratio with a large dynamic range. This requires special data manipulation and interpolation schemas, which may reduce its effect on the final resultant visual output.

-

Use dimensions in a different way. Most of the current visualization algorithms and applications are designed to visualize data assigned to 2D/3D spatial grids (e.g. CFD and medical grids). Grids (if they exist) in astrophysical datasets may contain different dimension types (e.g. redshift) in combination with the regular spatial domains. In some cases the dimensional information is mentioned as a type of metadata, so the visualization algorithm must first make a correct mapping between the data axes and the data values to be able to use current known visualization algorithms. This also limits the usage of general-purpose visualization packages in a quantitative manner.

-

Huge datasets. As noted in the previous section, data volumes from large-N particle simulations and high-resolution spectral data cubes routinely exceed millions (and often billions) of data points. These present problems relating to the memory and computational demands to handle such data sizes; the need to support high levels of interactivity, such as shifting quickly through different spatial scales (Brunner et al. 2002); or streaming of such data volumes.

4.2 Challenges for Astronomers

Scientific data visualization can and does provide opportunities to support a wide range of existing and planned astronomy research projects. Through our investigation of the literature, we have determined the following reasons why scientific visualization techniques may not have achieved a more widespread usage in astronomy:

-

The lack of quantitative tools that integrate seamlessly with visualization. This issue was identified by Norris (1994), but little progress has been made to address it. Using annotations and providing the user with quantitative information about data, combined with the qualitative visualization output, is an essential add-on to facilitate data analysis and exploration task. Only a few of the published astronomy visualization works show the need for interactive and quantitative visualization and provide a proposed solution (e.g. Amati et al. (2003), Ahrens et al. (2006), and Li et al. (2008)).

-

Visualization is not science for astronomers. The success of an astronomical project is judged by the science results it produces. The time invested by an astronomer in becoming an expert in using or developing visualization software must be balanced against the expected scientific gain. It is difficult to justify and obtain funding based purely on methodological approaches such as visualization and data mining, even if such an approach will demonstrably improve the scientific return (Ball and Brunner 2009). We think that this may be the main reason why most of the astronomy visualization trials neither lasted for a long period nor resulted in a widely used application.

-

Visualization does not do the science. The successful interpretation of visualization results is up to the scientist. The output may not represent a straightforward relationship or pattern. Visualization researchers aim to simplify this interpretation step, but adding a meaning to the final visualization output is still the astronomer’s task.

-

Adjustable parameters and technique configuration. Selecting a suitable iso-value, colour map, or transfer function is not always directly related to the dataset type or format. Sometimes this may require a deep understanding of both the data and the visualization technique. The focus of many projects was to visualize a certain object or was with a limited objective. Only a small number of projects were targeting general datasets or community usage of the software produced (e.g. Barnes et al. (2006) and Becciani et al. (2000, 2010)).

-

Usability and interoperability. Only the applications with focused visualization functionality, easy-to-use user interfaces, easy-to-deploy instructions, and dedication to a certain data type were widely used by the astronomical society. Also being a cross-platform application is an important consideration for usability.

-

There is a problem in citing the astronomy visualization effort or application. In preparing this review, we found it very difficult to determine an approximate number of users for each package. Quite often, astronomy-focused visualization software is not supported by an obvious, citable research paper, so there is a missed opportunity for developers to receive tangible credit for software that is being used to help support research. In some cases, we suspect that the lack of ongoing development or support for some applications may be tied to what is slowly being recognized as a wider issue for software developers in astronomy (Weiner et al. 2009).

-

Where do scientific visualization papers get published? The papers contributing to our review come from a range of astronomy journals, conference proceedings, and non-astronomy journals. The full selection of papers does not appear in ADS searching, meaning that astronomers may not be aware of their existence — particularly if the trend of not citing visualization papers continues. Our work serves a purpose in highlighting some of the more important and relevant papers in the field.

4.3 Six Grand Challenges for the Petascale Astronomy Era

We assert that visualization has a critical role to play in maximizing the scientific return of astronomical data in the Petascale Astronomy Era. However, to achieve this goal, work is required to overcome the following challenges:

-

Support for quantitative visualization. To advance astronomy visualization tools from ‘pretty picture’-generating tools into effective knowledge-discovery tools, astronomers need integrated quantitative support in addition to the currently provided qualitative output. Although the current qualitative data views are vital to give astronomers global pictures of their data, and have the potential to play an increased role in quality-control of data (see below), there is a need to extend astronomy visualization tools to better support ‘doing’ science. The ability to apply different data filters, inspect data points/objects for certain properties, overlay external catalogues/maps, apply mathematical operations, and select different sub-regions for further study are examples of missing tools. Most of these tools exist in current two-dimensional data analysis and processing packages (such as Karma) but these offer limited support for three-dimensional data.

-

Although providing such tools may seem easy, large datasets and low signal-to-noise properties will be a limitation for any effective implementation. Also, interaction with three-dimensional data will need a major change to enable effective implementation of such functionality (see below).

-

Effective handling of large datasets. Handling petabyte datasets will be a big challenge for most astronomical data-analysis packages. Real-time (or near real-time) interaction requirements worsen the situation for astronomy visualization. Additionally, storage requirements, networking costs, and transfer speeds will force many astronomers to change their way of doing science.

-

While most of the development effort now is going towards automated data analysis and information extraction systems, it is noteworthy that:

-

There is no automated system that reaches a 100% recognition rate. Specifically with the low signal-to-noise data that is regularly used for knowledge discovery, it is computationally challenging to achieve a high rate of automated pattern recognition.

-

Scientific visualization is expected to play an important role as a quality control tool for the output from different automated tools and data-reduction processes. Keeping all the raw data for some new astronomy instruments (e.g ASKAP and MWA) will not be feasible, so the trend will be to overwrite this data after the data reduction process is done. In such cases, the usage of scientific data visualization will be vital to detect and overcome any defects in the data-gathering and early analysis process.

-

Hassan et al. (2010) addressed some of these issues and provided a solution for visualizing larger-than-memory datasets with the aid of distributed processing and GPUs. However, improving data formats to support distributed storage and parallel file accessing, extending current data analysis tools to deal effectively with larger-than-memory datasets, and extending or enhancing current data-analysis tools with techniques more suitable to 3D datasets are still missing steps in the astronomical data processing pipeline.

-

Discovery in low signal-to-noise data. Effectively dealing with noise is an important issue when handling astronomy data. With large datasets, the low signal-to-noise properties found in astronomy limit the use of multi-resolution techniques and out-of-core methodologies. On the other hand, new discoveries usually happen near the noise level. Here, visualization plays a vital role in the absence of effective automated tools. Although noise suppression and removal is a signal-processing problem and may fall outside the scope of scientific visualization, advanced usage of colours to enhance comprehension and the development of customized transfer functions and shaders should be a priority for the next generation of astronomy visualization tools.

-

The use of colours in order to enhance comprehension has received little attention in astronomy. With the notable exception of Rector et al. (2005, 2007) there has been little work in investigating whether an application of colour science and visual grammar (such as composition, orientation, etc.) can improve cognition. This should include a detailed investigation of the benefits and limitations of using different colour maps and colour contrasts (such as harmonic colour maps — Wang and Mueller (2008)). Some effort has been made in the use of colour information to produce photorealistic rendering of simulation data, such as in the AMR work on first stars by Kähler et al. (2006); however, this is mostly with a public outreach product in mind. In the case of spectral data from a radio telescope, there is no such property as ‘photorealism’, and a pseudo-colour map must be used for intensity or fractional polarization.

-

Also, the use of transfer functions (or colour-mapping schemas) to provide astronomers with better insight into their data and suppressing noise will boost the effectiveness of visualization usage as a qualitative data-analysis technique (see Gooch (1995a, 1995b) for customized transfer functions developed for radio astronomy). There does not seem to have been any systematic investigation of the use of shaders in astronomy visualization, yet in other application domains this is one of the main areas of research interest (see Sato et al. (1998, 2000), Li et al. (2003), and Correa and Ma (2008) for example).

-

Better human–computer interaction and ubiquitous computing. The standard computer mouse is well-suited for interaction with two-dimensional data, but is limited when moving to multi-dimensional data. Immersive VR environments provide alternative interaction, often through a ‘wand’, which gives the user better control of navigation in a three-dimensional world, but this can require an expensive infrastructure or increased computational resources to drive. We believe that using relatively cheaper game controllers (e.g the Nintendo Wii controller), or programmable handheld interaction devices (specifically the Apple iPad), as tools for exploration and navigation within advanced visualization environments will be a better and affordable alternative. Such low-cost and easy-to-use solutions may help to bring advanced interaction to the astronomer’s desktop. Also, using ubiquitous computing methodologies to make interaction with visualization output more accessible and easier for astronomers may increase the adoption of 3D visualization (see Greensky et al. (2008) for an example of using such techniques in other scientific domains).

-

Better workflow integration. Improved integration between different data analysis and visualization tools will encourage the usage of scientific visualization. A typical example is providing two-way interaction between source-finders and 3D visualization tools, where the output of the source-finder is overlaid on the visualization output. Synthesis between data analysis and processing and visualization applications will provide the user with better control over, and give more insight into, the data analysis processes, and potentially speed up the knowledge discovery process.

-

Seamless astronomy,39 a concept advocated by Alyssa Goodman and colleagues, is an example which takes workflow issues one step further (see Goodman (2009) for a discussion on the role of ‘modular craftmanship’ in data visualization). Here, complete integration between different areas of the typical astronomer's workflow, such as linking searches for astronomical objects with related research papers, are all wrapped up within an interactive desktop environment. This is an extension of a service-oriented computing paradigm for astronomers, where the connectivity between applications is more natural. While early experimentation has centred on the World-Wide Telescope40 application, such an approach could incorporate 3D visualization either through support of remote visualization services or cross-platform browser-based applications.

-

Encouragement for adoption of 3D scientific visualization techniques. As we discussed in Section 4.2, there has been a somewhat limited effort by the astronomical community to develop widely used general-purpose visualization tools targeted at astronomical data. The lack of financial investment, compared to other disciplines which are motivated by both financial and social outcomes, limits the effort towards a complete astronomy visualization product with a suitably high level of documentation and support.

-

Furthermore, there appears to be a social issue limiting the usage of currently available tools. This may be due to the learning curve required to master a particular application, or the perceived low level of scientific return from the amount of time invested in using an alternative visualization technique. The lack of technical support, easy-to-use tools, and complete documentation contribute to limiting the amount of users benefits from existing tools.

-

We expect that this may change during the next decade with the increasing demand for better knowledge discovery and data-analysis pipelines, capable of dealing with the upcoming data avalanche. Building national or community facilities will provide a solution for this in the short term. Extending the use of remote visualization and data-analysis tools through the web platform will minimize the time and effort required to adopt visualization and offers a cost-effective solution by minimizing the total cost of ownership and reduces the need to transfer upcoming huge datasets.

5 Conclusion

We have investigated the state of scientific visualization research as applied to the domain of astronomy. As with the overall discipline, the use of computer-based scientific visualization in astronomy is still a young field. Over the last two decades, the astronomy community has invested substantially in domain-specific 2D and 3D visualization tools and techniques. For example, ‘Astronomical Data Analysis Software & Systems’ (ADASS) the major international annual astronomy software conference, has hosted more than 30 presentations on astronomy data visualization during this period. However, few research groups have concentrated for extended periods of time on improving visualization techniques for astronomy, and consequently the potential for new visualization approaches to improve scientific output in the discipline has not been thoroughly explored.

Scientific visualization is a genuine research technique in its own right and is a fundamental enabling technology for knowledge discovery. Great discoveries in astronomy are not always related to the patterns we already know — they are related to the identification of strange phenomena, unexpected relations, or unknown patterns. These cannot be achieved with an automated tool. There is still much that can be learnt about the process of scientific visualization and its domain-specific application in astronomy. With the Petascale Astronomy Era on the horizon, there has never been a more pressing need.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported under Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number DP0665574). It was undertaken as part of the Commonwealth Cosmology Initiative (CCI: www.thecci.org), an international collaboration supported by the Australian Research Council. We have benefited at various stages from disussions with David Barnes (Swinburne), and Alyssa Goodman and members of the IIC (Harvard). We thank Madhura Killedar (University of Sydney) for allowing us to visualize her cosmological dataset.This research has made extensive use of NASA’s Astrophysical Data System Bibliographic services.

References

Ahrens, J., Heitmann, K., Habib, S., Ankeny, L., McCormick, P., Inman, J., Armstrong, R., & Ma, K., 2006, Quantitative and comparative visualization applied to cosmological simulations. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 46, Institute of Physics Publishing, pp. 526–534Amati, G., Di Rico, G., Melotti, M., Ferro, D., & Paioro, L., 2003, AstroMD: a 3, visualization and analysis tool for astrophysical data. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 1, (1)

Arce, H. G., Borkin, M. A., Goodman, A. A., Pineda, J. E. and Halle, M. W., 2010, The COMPLETE Survey of Outows in Perseus. Astrophysical Journal, 715, 1170–1190

| The COMPLETE Survey of Outows in Perseus.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC3cXot1egur0%3D&md5=386982ef47723aa9e1ede462633c4171CAS |

Aschwanden, M., 2010, Image Processing Techniques and Feature Recognition in Solar Physics. Solar Physics, 1–41

Ball, N. and Brunner, R., 2009, Data mining and machine learning in astronomy. International Journal of Modern Physics, D 1, 1–53

Barnes, D., Fluke, C., Bourke, P. and Parry, O., 2006, An Advanced, Three-Dimensional Plotting Library for Astronomy Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 2, 82–93

| An Advanced, Three-Dimensional Plotting Library for AstronomyCrossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

Barrett, P., & Bridgman. W., 2000, PyFITS. a Python FITS Module. In: Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems IX. Vol. 216, p. 67

Becciani, U., Antonuccio-Delogu, V., Buonomo, F., & Gheller, C., 2001, An Integrated Procedure for Tree N-body Simulations: FLY and AstroMD. In: Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems X. Vol. 238, p. 503

Becciani, U., Antonuccio-Delogu, V., GhellerC., Calori, L., Buonomo, F., & Imboden, S., 2000, AstroMD. A multi-dimensional data analysis tool for astrophysical simulations. Arxiv preprint astroph/0006402

Becciani, U., Costa, A., Antonuccio-Delogu, V., Caniglia, G., Comparato, M., Gheller, C., Jin, Z., Krokos, M. and Massimino, P., 2010, VisIVO – Integrated Tools and Services for Large-Scale Astrophysical Visualization Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 122, 119–130

| VisIVO – Integrated Tools and Services for Large-Scale Astrophysical VisualizationCrossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

Beeson, B., Barnes, D. and Bourke, P., 2003, A distributed-data implementation of the perspective shear-warp volume rendering algorithm for visualisation of large astronomical cubes Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 20, 300–313