A northernmost occurrence record of Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) – a molecular identification from Exmouth, Western Australia

Melissa A. Millar A * , Kelly A. Waples A , Holly C. Raudino A and Kym Ottewell

A * , Kelly A. Waples A , Holly C. Raudino A and Kym Ottewell  A B

A B

A

B

Abstract

Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) is one of the least known beaked whales. Its distribution has been described as circumpolar, between latitudes 26°S and 50°S in the Southern Hemisphere based on scarce at-sea sightings and strandings. In March 2024, the remains of a cetacean were found in the Jurabi Coastal Park in North West Cape, Western Australia, 21°48′S, 114°06′E. Heavy predation on the carcass did not allow morphological identification. DNA sequencing was used to verify its identity as T. shepherdi, representing a 600 km extension to the previous northernmost record for this species.

Keywords: cetacean, DNA sequencing, molecular identification, Shepherd’s beaked whale, species distribution, Tasmacetus shepherdi, Western Australia, Ziphiidae.

Introduction

The beaked whales (family Ziphiidae) comprise 21 species and are one of the least studied groups of mammals in the world (Dalebout et al. 2004). Sightings at sea are rare and knowledge of individual species and their ranges varies considerably (Mead 1989; MacLeod et al. 2006). Knowledge on the distributions of the 14 Southern Hemisphere species is particularly lacking (Hooker et al. 2019). Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) is one of the least known of the beaked whales (Mead 1989, 2008), with most information coming from strandings in New Zealand and the Chatham Islands, Juan Fernandez Islands, Argentina, Tristan da Cunha, and Australia (Pitman et al. 2006; Hevia et al. 2011; Best et al. 2014). From 2008 to 2017 there have been a series of vessel based at-sea sightings and aerial observations in coastal waters of southern Australia and New Zealand (Donnelly et al. 2018; Dawson et al. 2024), as well as the first underwater sighting in waters of a remote archipelago of Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic (Thompson et al. 2019). Based on stranding locations, and at-sea sightings (Mead 1989, 2008; Towers and Tixier 2022), the circumpolar distribution of T. shepherdi has been historically thought to encompass temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere between latitudes 33°S and 50°S.

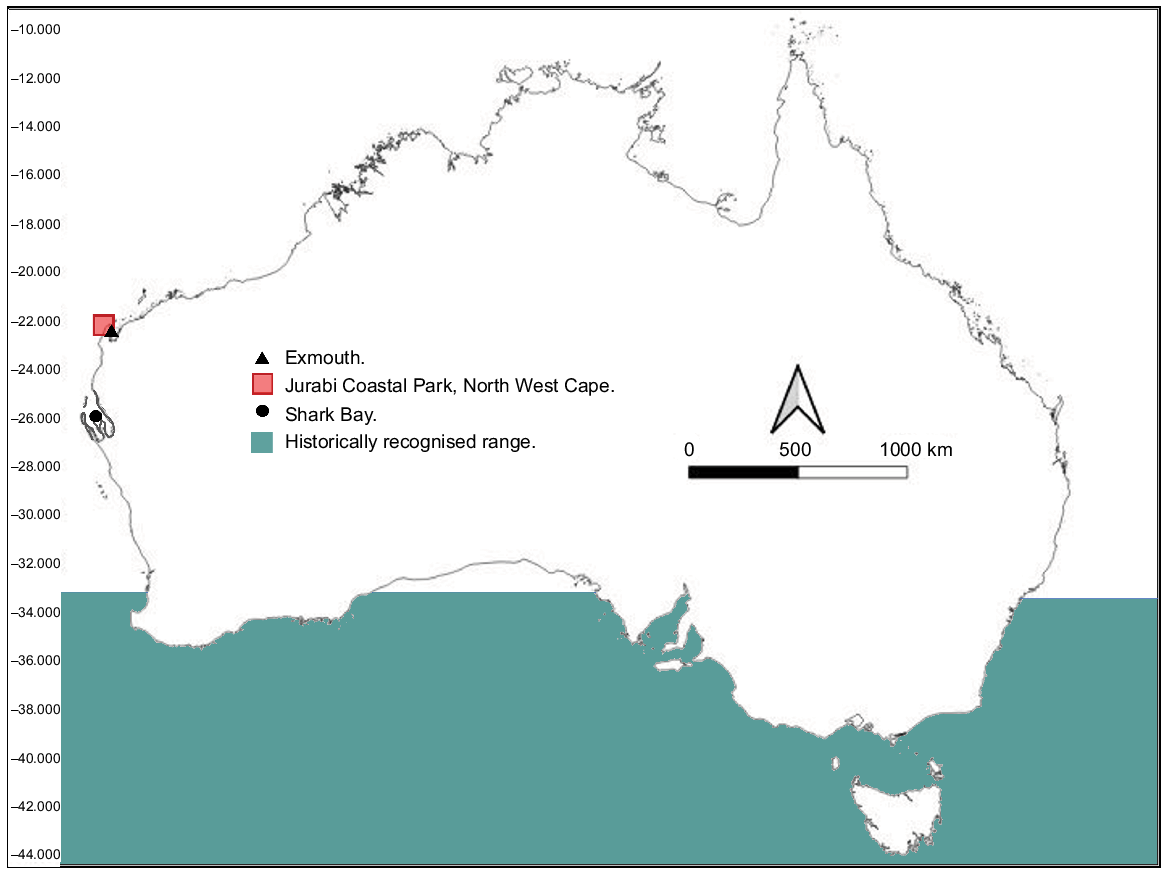

Western Australia is renowned for having a higher species diversity of beaked whale strandings than other Australian states and regions (Groom et al. 2014). There have been three recorded stranded specimens of T. shepherdi in Western Australia with the first two recorded within the historically recognised latitudinal range for the species (Groom et al. 2014). More recently, genetic and morphological identification of a ‘moderately’ decomposed stranded carcass from Shark Bay on the west coast of Australia in 2008 extended the northernmost range to 26°20′S (Holyoake et al. 2013), confirming the species’ presence at warmer latitudes (Fig. 1).

Map of Australia showing the location of the town of Exmouth, the Jurabi Coastal Park (2024 stranding), Shark Bay (2008 stranding) and the historically recognised range of Tasmacetus shepherdi in southern waters below the 33rd parallel.

Identification of stranded beaked whales can be difficult even when the whole animal is available for examination by experts due to a lack of, or few, distinguishing external features, and typically subtle differences in diagnostic morphological characteristics, as well as sexual and age-related dimorphism (Dalebout et al. 2004). Identification is particularly difficult with depredated or decomposed carcasses. Molecular genetics provides a powerful tool to assist in identification of potentially cryptic specimens of beaked whales, including those in states of heavy depredation and decomposition that preclude morphological identification. Samples for molecular genetic analysis are easily collected in the field, even from such specimens. Here we report on the genetic identification of a stranded, heavily depredated, T. shepherdi carcass from Jurabi Coastal Park, near Exmouth, Western Australia.

Materials and methods

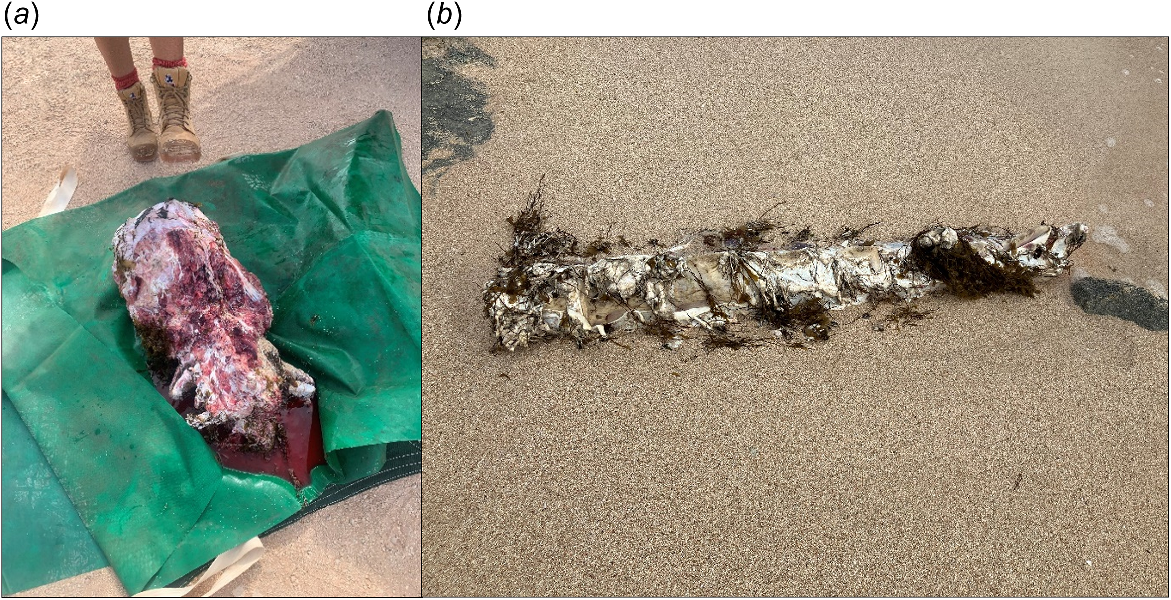

On 18 March 2024, the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) received a report of a whale carcass at Hunter’s Beach, in the Jurabi Coastal Park, on the North West Cape, Western Australia, 21°48′S, 114°06′E (Fig. 1). DBCA staff present observed sharks feeding on the carcass in shallow water with part of the dorsal and lateral side including one pectoral fin visible. The pectoral fin was small, dark in colour and paddle shaped – common to many beaked whale species. The skull with all skin and most of the flesh removed and section of vertebrae were later collected from the site (Fig. 2). It was not possible to visually identify the species from these remains. A tissue sample (blubber with some skin) was taken from the remains for species identification by molecular genetic analysis. The sample was stored in 100% ethanol at ambient temperature until laboratory processing. Part of the tissue sample was also provided to the Western Australian Museum, accession number WAM TM1234. The remains of the carcass were disposed of.

Whale specimen showing condition of remains found at Hunters Beach, Jurabi Coastal Park, Western Australia, 18 March 2024: (a) skull; (b) vertebrae. Photography by Michael Cox, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.

Molecular identification of species

Whole genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 4 mm3 of blubber and skin tissue using an overnight digestion in buffer (100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 400 mM NaCl, 0.6% SDS, 0.2 mg Proteinase K) and a standard salting out extraction protocol (Sunnucks and Hales 1996). DNA concentration was assessed using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

The mitochondrial DNA control region (D-Loop) sequence has been shown to be sufficient for genetically discriminating ziphiid members, based on intra- and interspecific genetic variation (Dalebout et al. 2004). A ~900 bp fragment of the 5′ end of the mtDNA control region was amplified by PCR using the displacement D-Loop primers of Wada et al. (2003). Two PCRs were conducted in 25 μL reactions containing 2 μL of 10 ng μL−1 genomic DNA, 5 μL All TAQ PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), 2.5 μL of 2 μM F/R primers, and 15.5 μL dH2O, with a hotstart PCR program following Shaw et al. (2007). The PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel to visualise and confirm the presence of single PCR products in each reaction.

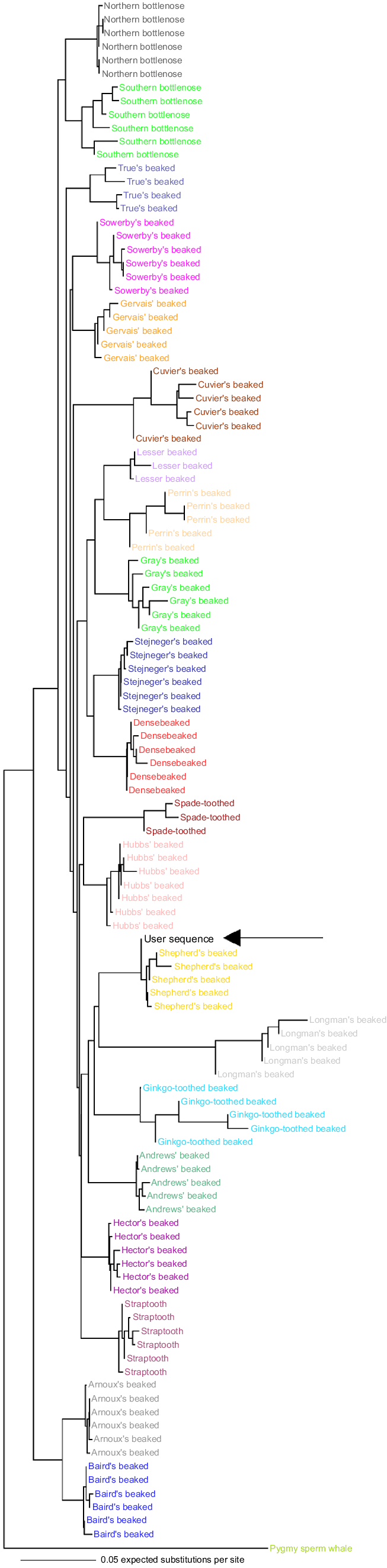

A second round of two amplification reactions was conducted with two additional aliquots of DNA, and the PCR products were purified and sequenced by a commercial service (State Agricultural Biotechnology Centre, Murdoch University, Western Australia) using ABI BigDyev3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Replicate sequencing products produced identical DNA sequences which were edited using the program Geneious Prime v2023.2.1 (The Biomatters Development Team 2023). We submitted a 916 bp sequence to the database Witness for Whales, an annotated and curated set of reference nucleotide sequences from a comprehensive and representative range of cetaceans (Ross et al. 2003). A neighbour-joining tree was then constructed using the ‘Ziphiidae’ Vs4.3’ database for the mitochondrial DNA control region with 1000 bootstraps (Fig. 3). The DNA sequence is available at GenBank, accession number PP982850.

Dendogram showing the position of the stranded specimen in relation to other Ziphiidae contained in the validated database compiled by Ross et al. (2003) based on mitochondrial DNA control region sequences. The stranded specimen is labelled as USER SEQUENCE and indicated with an arrow. Bootstrap values are provided.

Results

Genetic analysis identified the whale specimen as T. shepherdi with very strong bootstrap support (99) for placement in the Shepherd’s beaked whale clade (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Genetic analysis is a useful tool for identifying specimens of poorly known species, especially stranded specimens that have undergone predation and/or advanced decomposition and can aid in elucidating the distributions of these little-known marine mammals. Given their pelagic habitat, beaked whales such as T. shepherdi are not only difficult to study but are rarely sighted alive. The Southern Hemisphere and temperate distribution of Shepherd’s beaked whale in deep waters has been historically based on information from limited strandings and rare at-sea sightings. It has been suggested that the species undertakes northern movement in summer approaching continental seas (Van Dyck and Strahan 2008). The T. shepherdi specimen described by Holyoake et al. (2013) from a stranding at Shark Bay was only moderately decomposed and not likely to have drifted far before making landfall. The specimen identified here is likely to have died at sea and drifted only a short distance before stranding, given the advanced state of predation as opposed to decomposition. The Jurabi Coastal Park is roughly 600 km, or 5° latitude north of Shark Bay, and is now the northernmost recorded occurrence for T. shepherdi.

Ethical standards

This research was not covered by any regulation and formal ethical approval was not required.

Data availability

The new sequence datum that supports the findings of this study is openly available from the NCBI GenBank database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accession number PP982850.

Author contributions

All authors conceived and designed the study; MAM acquired the data, analysed and interpreted the data and prepared the draft article and revisions; HCR and KAW coordinated sample acquisition and contributed to article revision; KO analysed and interpreted the data and contributed to article revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Riley Carter and Michael Cox who responded to the stranding, collected samples and sought advice on species identification.

References

Best PB, Smale MJ, Glass J, Herian K, Von Der Heyden S (2014) Identification of stomach contents from a Shepherd’s beaked whale Tasmacetus shepherdi stranded on Tristan da Cunha, South Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 94, 1093-1097.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dalebout ML, Baker CS, Mead JG, Cockcroft VG, Yamada TK (2004) A comprehensive and validated molecular taxonomy of beaked whales, family Ziphiidae. Journal of Heredity 95, 459-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dawson S, Barlow J, Guerra M, Leunissen E, Webster T, Rayment W (2024) Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) produces a diverse variety of ultrasonic pulses. Marine Mammal Science e13199.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Donnelly DM, Ensor P, Gill P, Clarke RH, Evans K, Double MC, Webster T, Rayment W, Schmitt NT (2018) New diagnostic descriptions and distribution information for Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) off Southern Australia and New Zealand. Marine Mammal Science 34, 829-840.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Groom CJ, Coughran DK, Smith HC (2014) Records of beaked whales (family Ziphiidae) in western Australian waters. Marine Biodiversity Records 7, e50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hevia M, Arcucci D, Belgrano J, Cipriano F, Failla M, Gasparrou C, Hodgins N, Kröhling F, Reyes Reyes M, Reyes R, Tossenberger V, Iñíguez Bessega M (2011) Strandings of six beaked whales in Santa Cruz province, southern Argentina (1998–2011). Paper SC/63/DM3 submitted to the international Whaling Commision Scientific Committee meeting (IWC), p. 8.

Holyoake C, Holley D, Spencer PBS, Salgado-Kent C, Coughran D, Bejder L (2013) Northernmost record of Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) – a morphological and genetic description from a stranding from Shark Bay, Western Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 19, 169-174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hooker SK, De Soto NA, Baird RW, Carroll EL, Claridge D, Feyrer L, Miller PJO, Onoufriou A, Schorr G, Siegal E, Whitehead H (2019) Future directions in research on beaked whales. Frontiers in Marine Science 5, 514.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

MacLeod CD, Perrin WF, Pitman R, Barlow J, Ballance L, D’Amico A, Gerrodette T, Joyce J, Mullin KD, Palka DL, Waring GT (2006) Known and inferred distributions of beaked whale species (Cetacea: Ziphiidae). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 7, 271-286.

| Google Scholar |

Pitman RL, Van Helden AL, Best PB, (Tony) Pym A (2006) Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi): information on appearance and biology based on strandings and at-sea observations. Marine Mammal Science 22, 744-755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ross HA, Lento GM, Dalebout ML, Goode M, Ewing G, McLaren P, Rodrigo AG, Lavery S, Baker CS (2003) DNA Surveillance: web-based molecular identification of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Journal of Heredity 94, 111-114.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shaw J, Lickey EB, Schilling EE, Small RL (2007) Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany 94, 275-288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sunnucks P, Hales DF (1996) Numerous transposed sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I-II in aphids of the genus Sitobion (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Molecular Biology and Evolution 13, 510-524.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

The Biomatters Development Team (2023) Geneious Prime.V 2023.2.1. Auckland, New Zealand. Available at http://www.geneious.com

Thompson CDH, Bouchet PJ, Meeuwig JJ (2019) First underwater sighting of Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi). Marine Biodiversity Records 12, 6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Towers JR, Tixier P (2022) Indian Ocean sighting of Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) helps confirm circumpolar distribution in southern hemisphere. Aquatic Mammals 48, 462-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wada S, Oishi M, Yamada TK (2003) A newly discovered species of living baleen whale. Nature 426, 278-281.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |