Purpose-driven approaches to age estimation in Australian flying-foxes (Pteropus)

Cinthia Pietromonaco A B * , Douglas Kerlin

A B * , Douglas Kerlin  A , Peggy Eby A C , Hamish McCallum A , Jennefer Mclean D , Linda Collins E and Alison J. Peel

A , Peggy Eby A C , Hamish McCallum A , Jennefer Mclean D , Linda Collins E and Alison J. Peel  A B

A B

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

Aging is a ubiquitous component of the life history and biological function of all species. In wildlife studies, estimates of age are critical in order to understand how a species’ ecology, biology and behaviour vary in parallel with its life-history events. Longitudinal studies that track individuals as they age are limited in fruit bats, as recapture is difficult for vagile species with nomadic lifestyles. Most studies estimate age by the broad categorisation of individuals with similar biological characteristics or morphometrics into age classes (e.g. sub-adult and adult). In this review, we systematically compile and compare the age classifications used across a range of studies on Australian flying-foxes (Pteropus). We discuss the associated challenges of those classifications and identify current knowledge gaps. The terminology, methodology and explanations behind age classifications were inconsistent across reviewed studies, demonstrating that age classifications are highly subjective – particularly when identifying reproductively immature individuals. Downstream analyses and cross-disciplinary data use are likely to be compromised as a result. Further known-aged studies of flying-foxes would assist in clarifying variations of key parameters among non-adult individuals. We also encourage greater consistency in age classification and reporting, ensuring that classifications are well defined and biologically sound.

Keywords: behaviour, developmental biology, growth, life history, longevity, morphology, population biology, reproduction.

Introduction

Flying-foxes (Pteropus spp. bats) are highly mobile species that can be found in Australia, South-east Asia, the Indian subcontinent and island groups including, and not limited to, the islands of the Indian and western Pacific Ocean (Hall and Richards 2000). They are of high ecological importance to forest ecosystems due to their essential role in long distance pollination and seed dispersal (Pierson and Rainey 1992; Southerton et al. 2004). These positive contributions can sometimes be overshadowed by human–wildlife conflict in urban areas (Tait et al. 2014), with fruit growers (Aziz et al. 2016), and the identity of some species as primary reservoir hosts of viruses that are highly fatal if transmitted to humans (zoonoses), including henipaviruses (Hendra virus and Nipah virus; Breed et al. 2011); and Australian Bat Lyssavirus (Mollentze and Streicker 2020; Streicker and Gilbert 2020). Effective conservation, management and disease mitigation efforts are facilitated by having a fundamental and detailed understanding of the ecology and immunology of flying-foxes (Eby et al. 2023). In turn, an individual’s age is a critical underlying biological driver, yet this is often inconsistently documented and reported (Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009; Jackson et al. 2016).

Aging is a fundamental component of the life history and biological function of all species. Particularly for long-lived individuals, such as flying-foxes, accounting for individual age is essential to a broad range of studies, including those assessing population dynamics, genetics, evolutionary ecology and disease ecology (Veiberg et al. 2020). Population models rely on age-based data for mortality and fecundity rates, and these models can subsequently assist in management and conservation (Hayman and Peel 2016; Hecht 2021). For instance, human-induced threats to flying-foxes, such as powerlines and barbed wire fences, have been found to disproportionately affect younger bats and therefore affect recruitment, conservation outcomes and management goals (Divljan et al. 2006). Accurate age data are important for determining population viability, since characteristics such as short weaning periods or delayed sexual maturity have been shown to increase vulnerability to direct conservation threats (Gonzáles-Suárez et al. 2013). Moving beyond broad age categories (for example, adult, juvenile) to more specific ages can provide additional insights. For example, age-specific serology can infer mechanisms of viral maintenance in populations and the duration that pups are protected from infection by maternally derived antibodies (Peel et al. 2018; Edson et al. 2019). Life-history theory is central to evolutionary and ecological research and requires knowing the age at which major demographic processes occur. A comprehensive understanding of age is crucial as it forms the foundation for ensuring the confidence and effectiveness of research studies (Morris 1972). Additionally, age knowledge plays a pivotal role in the development of management and conservation practices that are derived from such research.

Chronological age and biological life stages

Biological age is a multi-factorial, complex and species-specific concept arising from a multitude of theories on the biology of aging (Cohen 2018). Chronological age refers to the time from birth to the present time for a specified individual (Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009) and is usually measured in years or months, whereas biological age reflects the physiological changes throughout an individual’s life and is ultimately measured by factors such as change in morphology or function (Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009). Biological aging is therefore often reflected as an age range or age class, such as juvenile, sub-adult and adult. Wildlife studies use a combination of factors to estimate age, with most deferring to biological age-based estimations to assign an age class, important to the life history, that approximately correlates with chronological age. For example, an individual can be described as a sexually mature ‘adult’ based on well-developed genitals (Vardon and Tidemann 1998; Wilkinson and McCracken 2003), and this age class is subsequently associated with a chronological age range that is species-specific.

Several biological milestones can be described for flying-foxes. From birth, flying-fox pups cling underneath their mother’s wing on her chest to nurse for several weeks using their specialised curved milk teeth (Nelson 1965; Hall and Richards 2000). Tooth development continues during the lactation period, with eruption of a full set of permanent dentition by ~20–30 weeks (Gonzale and Close 1999; Divljan et al. 2011). After a few weeks of being fully dependent, pups will be left in the roost while their mothers forage during the evenings. The transition to independence is associated with independent flight and foraging from ~13–17 weeks (Nelson 1963, 1965; Hall and Richards 2000). Between this time and when mating season commences, they are then weaned and become fully independent (by ~22 weeks). The period between independence and becoming reproductively active varies among species and successful breeding is likely to occur at different ages for male and female flying-foxes. In grey-headed flying-fox, Pteropus poliocephalus, females typically breed annually after reaching sexual maturity. Mating can first occur from a chronological age of ~1.5 years and birthing first occurs at a chronological age of ~2 years (Hall and Richards 2000; Martin and McIlwee 2002). Studies have indicated that approximately one-third of individuals may not breed until their third year, however since age was estimated only from weight or forearm, the precise estimates of the proportion of females breeding in their second or third year should be treated with caution (Nelson 1963; Vardon and Tidemann 1998). By contrast, although the visibility of sexual viability (puberty) is reported to start in males in the second breeding season (Hall and Richards 2000), males may only be able to produce effective sperm in the third breeding season, at a chronological age of ~2.5 years (Nelson 1963; Hall and Richards 2000; Churchill 2008). Subsequently, the scrotum and testicles increase and decrease in size based on timing of the breeding season (McGuckin and Blackshaw 1991; O’Brien et al. 1993; Hall and Richards 2000). The presence of dominant older males within camps likely contributes to further delays in successful copulation for younger males (Welbergen 2006); an individual’s age drives its social interactions with other individuals in the population more broadly (Nelson 1965; Holmes 2002). Our understanding of the features in the life cycle of other species of flying-fox are limited, however, some species have been observed to vary in timing of breeding seasons (Vardon and Tidemann 1998; Mitchell 2021) and number of birth periods per year (McGuckin and Blackshaw 1991; Hall and Richards 2000; Churchill 2008).

Inference from banded studies suggest that the average lifespan for P. poliocephalus and Pteropus alecto (black flying-fox) is ~7 years (Vardon and Tidemann 2000; Tidemann and Nelson 2011), however, it is estimated (using tooth growth rings) that wild individuals can live over 20 years, and captive individuals may live over 30 years (Hall and Richards 2000). Further research is needed to explore whether flying-foxes experience a period of senescence, such as a decline in reproductive capacity, as they age.

Methods for ageing

In domesticated species, longitudinal datasets arising from regular monitoring of the development of an individual over time can assist with identifying the relationship between biological and chronological age (Morris 1972). For wild animals, obtaining these records requires tagging and repeated recapture of individuals, which is often infeasible for bats (Brunet-Rossinni and Austad 2004; Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009). The recapture of known-age flying-foxes is rare because they are highly mobile and regularly change camps (Parsons et al. 2011), contributing to the difficulty in obtaining longitudinal data for aging (Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009). As a result, various ageing techniques have been developed and applied to determine the age of bats using cross-sectional observations and data from captive populations. Biological age has typically been estimated by demographic observations (such as the timing of birth pulses and mating periods), morphological observations (such as body mass, forearm length and tooth wear), and anatomical and physiological observations (such as development of primary and secondary sex characteristics and analysis of hormones). However, even with clear descriptions, the reliability of these morphological measurements can be influenced by subjectivity, such as assessing tooth wear, and inter-user variability, for example differences in using callipers v. rulers to measure forearm length during implementation.

Estimates of chronological age have been obtained from analysis of teeth (Brunet-Rossinni and Wilkinson 2009), and more recently, DNA methylation (Wilkinson et al. 2021). Histologically, counting the annuli formed by the incremental growth of cementum and dentine tissues in teeth has been identified as a reliable source for accurately ageing mammalian species, including pteropodid bats (Fancy 1980; Cool et al. 1994; Divljan et al. 2006). When tested on known-aged bats, the counting method was found to be less reliable for individuals over 10 years old compared to measuring cementum thickness (Cool et al. 1994; Divljan et al. 2006). Counting cementum thickness has subsequently been applied widely in pteropodid bats (Fox et al. 2008; Hayman and Peel 2016; Peel et al. 2016, 2017; Brook et al. 2019). Chronological age (in days) can also be determined by examining tooth eruption and the replacement of deciduous teeth, however, is limited to the specific transitional period (weaning) during early life (Divljan et al. 2011). Assessing DNA methylation in bat wing tissue samples is a promising new approach to accurately predict chronological age in bats (Wilkinson et al. 2021), however, this method is still being developed and can be costly for large sample sizes (Kurdyukov and Bullock 2016).

Owing to the requirements for invasive sampling and analysis costs of these chronological ageing approaches, demographic observations and morphometrics remain the most common method for ageing bats.

This review was initiated following the recognition of substantial inconsistencies in age assignments across flying-fox studies, particularly among various ecological disciplines, such as disease, evolution and population ecology, and also between ecological studies and age classifications used by wildlife rehabilitators. The inconsistency across sources stems from different objectives for age classification among disciplines and the varying cut-offs and terminology used, making it difficult to compare among studies. The aims of this review are to document the range of age classifications used for flying-foxes, discuss their appropriateness and identify where knowledge gaps lie.

Materials and methods

The objective of the investigation was to identify and summarise relevant literature on age classification in Australian flying-foxes (genus Pteropus) by including peer-reviewed literature that either studied age or aging in Australian flying-foxes or used age classifications. Grey literature (such as wildlife carer manuals) was also considered valuable for this review to capture the experience and knowledge of those regularly assessing age in individual flying-foxes and observing age-related growth trajectories while individuals are in care.

Search procedure

This systematic review compiled literature from two databases, PubMed and Web of Science (WoS). Article titles, abstracts and keywords were examined for relevant search terms using Boolean operators: Australia AND (‘Flying fox’ OR Pteropus OR Flying-fox) AND (Age Classification OR Ageing OR Growth OR Development OR Age). Studies were additionally restricted to English language. Reference tracing of included studies was performed to add additional peer-reviewed literature that did not appear in the database search but was relevant to the aims of the review. A research field protocol (BatOneHealth 2021) and wildlife rehabilitator manuals were included as grey literature, including the widely used ‘The Flying-fox Manual’ (ver. 3; Pinson 2022) and the ‘BCRQ Bat Rescue Manual’ (vol. 1; Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 2022). Finally, personal communications provided additional comparable information, including insights from Storm Stanford (WIRES, Sydney, NSW, August 2023), Lib Ruytenberg (WIRES, Lismore, NSW, August 2023), Linda Collins (Adelaide, SA, October 2023), and Jennefer Mclean (Tolga Bat Hospital, Atherton, Qld, July 2023).

Article screening and selection

Titles and abstracts were screened and peer-reviewed articles that were returned by the keyword search, but did not meet the initial inclusion criteria, were excluded. If this was not clear, then the main text was also assessed. Articles from each database were combined and then filtered for unique results. The remaining articles were then screened first by geographic region (restricted to studies conducted in Australia and its offshore territories), followed by study focus (limited to research on wild Pteropus populations) and then relevance to age. We focused this review on Australian flying-foxes as a case study because they represent a well-studied group with extensive multidisciplinary research, making them ideal for examining cross-disciplinary challenges in age classification. The inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed studies that examined aging in flying-foxes or provided age classifications in the methods section, either for analysis purposes or as supplementary information in empirical format. From each source, baseline information such as species of study, year of study and geographic information was recorded. Information on age extracted from each methods section included terminology for age classifications and the methods behind determining those classifications (e.g. cut-offs or ranges of morphometrics and the chronological age range assigned). In some cases, prior publications were cited for ageing methods, and so those publications were then included in the database if not already present and processed as described above.

Results

Literature search

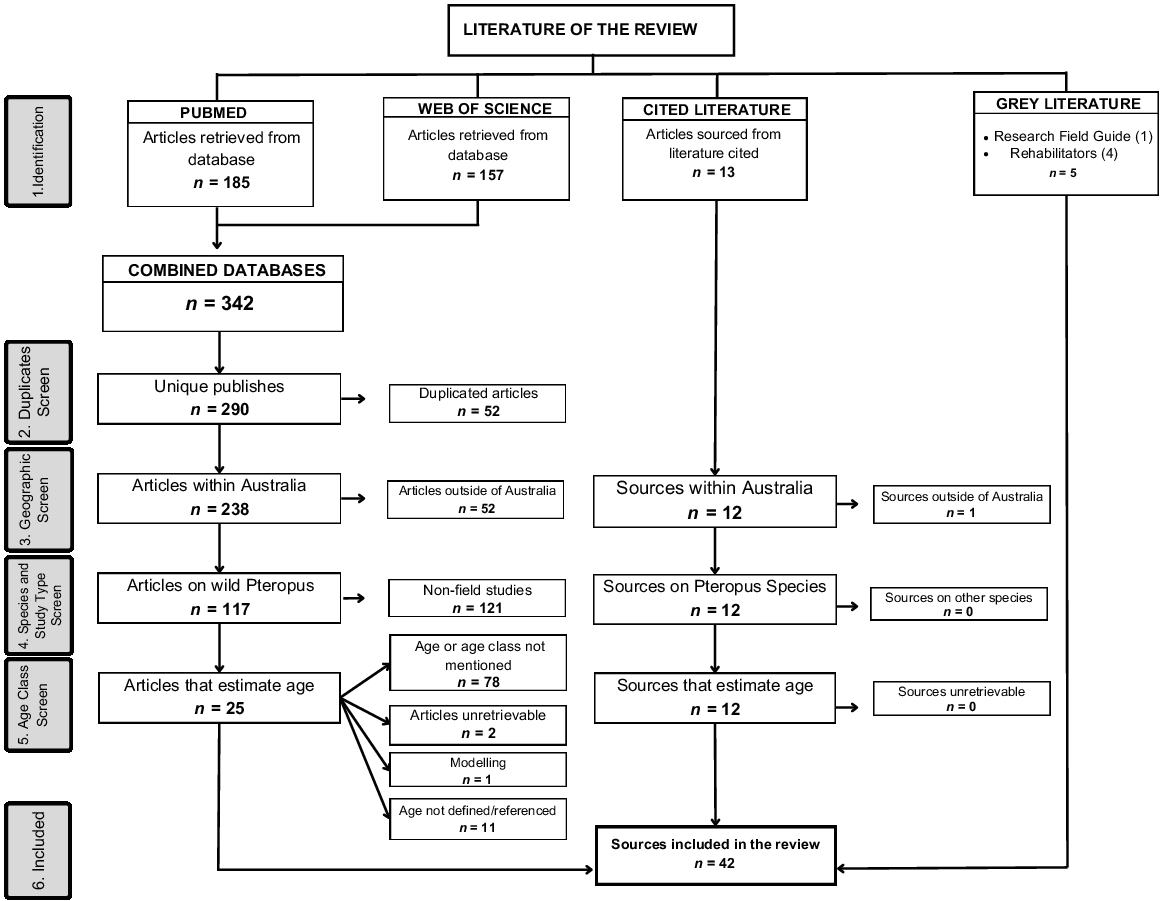

A total of 342 publications were retrieved from PubMed and WoS, of which 52 were duplicated and removed, leaving 290 unique papers (Fig. 1). The first round of filtering was to include those investigated within mainland Australia and offshore territories (n = 238). From the remaining publications, a second round of filtering removed any article that was not focused on populations from the Pteropus genus (including review papers and studies focused solely on bat cell lines or viral isolation) leaving 117 articles. The final filter sorted through the body of each article including the supplementary information and retained any paper that studied or estimated age (n = 39). From those remaining 39, 2 were unable to be sourced, 1 was a paper using estimated age groups for modelling and 11 mentioned age, however, did not define or reference their methods. As such, those 14 were not included, leaving 25 articles in the review. An additional 12 articles were identified by reference tracing. In total, this review consists of 42 documents: 25 from literature search, 12 from tracking citations and 5 pieces of grey literature.

Meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram illustrating the systematic review process of including sources estimating age of flying-foxes.

We have included a summary of the baseline information and ageing methods extracted for each source in the Supplementary Table S1. We note that peer-reviewed publications that assigned age classes to flying-foxes, but did not include the terms age, aging, age classification, growth or development in the title, abstract or keywords, and other unpublished work would have been omitted from our database search results. Detailed assessment of a random selection of this larger set of publications indicated that the key challenges identified in our results were representative across the broader set of publications.

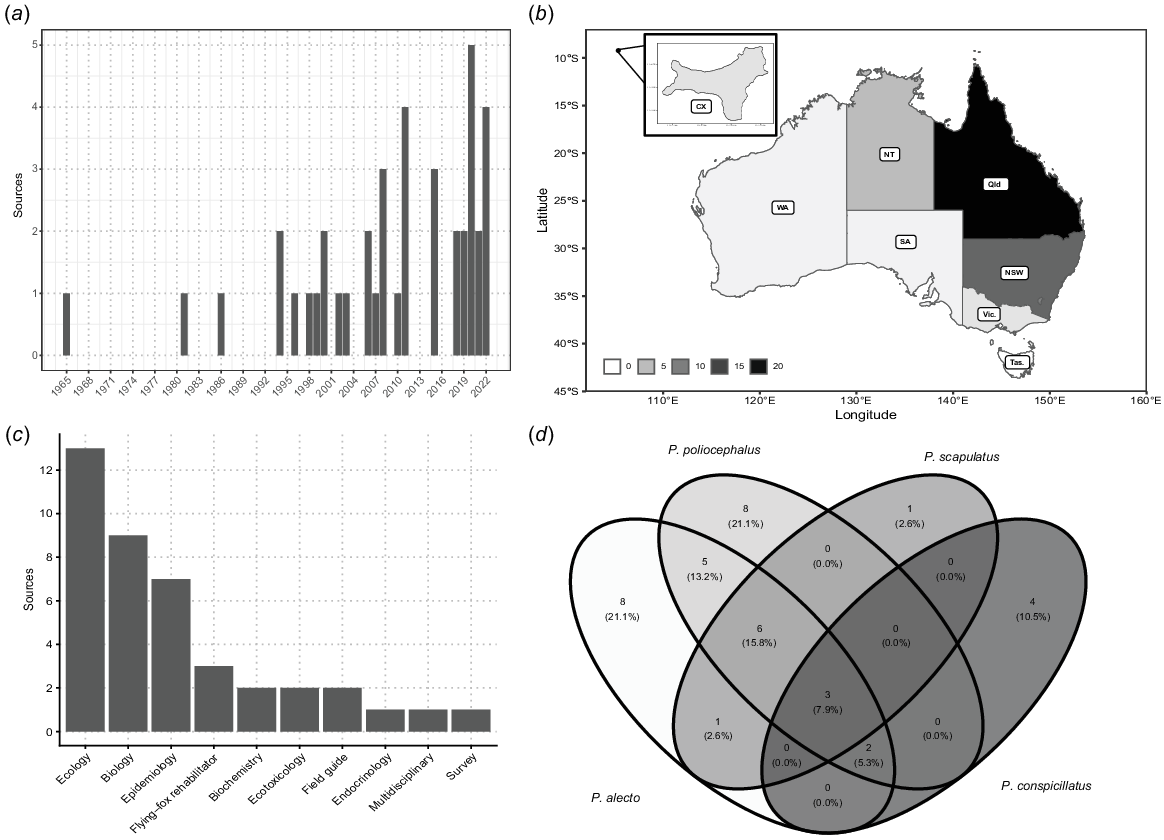

The extracted data span 57 years of publications, from 1965 to 2022, with the majority (90%) published after 1993 (Fig. 2a). The highest number of publications was recorded in 2020 and 2022, with five each. The studies were conducted in various locations and sometimes (n = 6) in multiple states across Australia, with the majority of research taking place in Queensland (n = 21) followed by New South Wales (n = 13), Northern Territory (n = 5), Christmas Island (n = 4) and Victoria (n = 2) (Fig. 2b). No articles were found for the remaining states and territories. Churchill (2008), Hall (1987), Hall and Richards (2000) and Pinson (2022) summarised general field information on flying-foxes and were not linked to a particular study or state.

Summary of literature in the review according to (a) number of papers by year of publication, (b) number of papers within each Australian state and territory, (c) number of papers within a discipline, and (d) percent of overlap of flying-fox species across each paper.

Age estimation was mentioned in 84.2% (34) of the 42 sources. The remaining included sources were growth studies, either with (7.9%) or without (7.9%) reference to age class. Most were ecological studies, followed by biology and epidemiology (Fig. 2c). Citation of ageing methods occurred both within and across disciplines, for example, especially between biological and ecological studies (Supplementary Fig. S1). One-third of sources (n = 14) did not clearly reference their ageing methods. In two cases, ageing methods originally described for a non-Australian Pteropus species (Epstein et al. 2008) were applied to Australian species. The original source was not included in this study as it did not meet inclusion criteria of being on Australian Pteropus species.

There are eight known Pteropus species within Australian states and territories (Hall and Richards 2000; Churchill 2008). Of those, five are included in this paper including P. poliocephalus, P. alecto, Pteropus scapulatus (little red flying-fox), Pteropus conspicillatus (spectacled flying-fox) and Pteropus natalis (Christmas Island flying-fox). P. alecto and P. poliocephalus were included in the greatest number of studies (n = 25 and 24 respectively; Fig. 2d). Of the studies that investigated multiple species, the most common combination was P. poliocephalus, P. alecto and P. scapulatus (n = 6), followed by the combination of P. poliocephalus and P. alecto (n = 5). Studies on P. natalis were single species only, except when mentioned in field identification guides.

Age class terminology

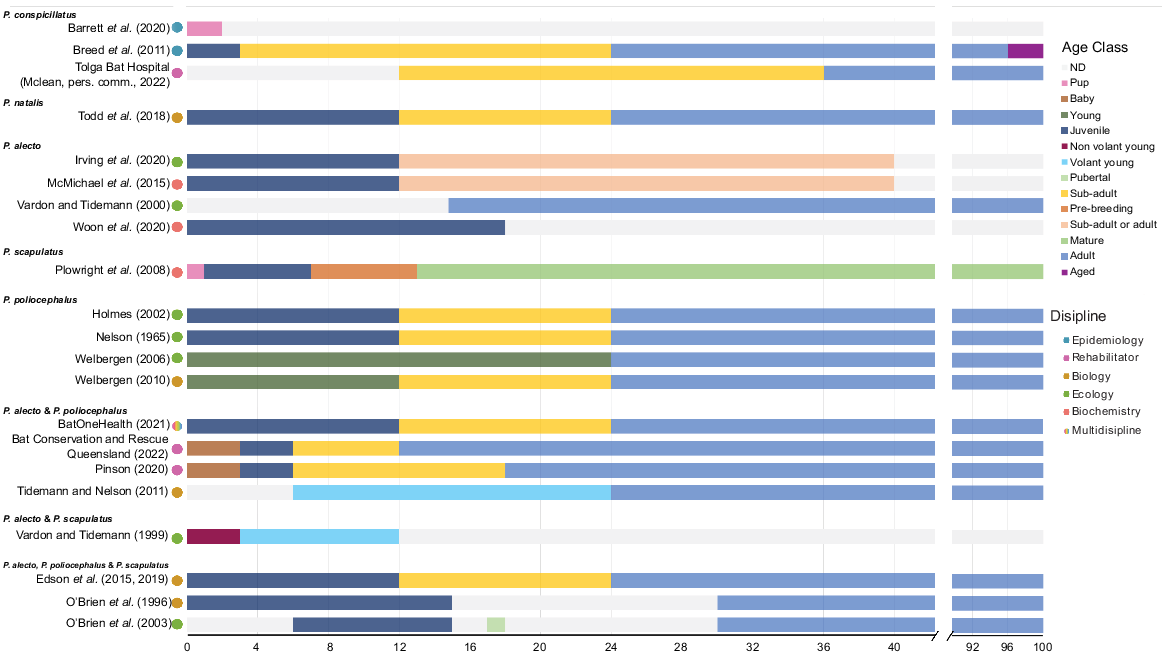

Most commonly (22% of sources), individuals were assigned to one of three age classes – juvenile, sub-adult and adult – however, some sources included other terms such as: pup, baby, non-volant young or neonate when referring to dependent young; or ‘sexually immature’, volant young, independent juvenile and pre-breeding for individuals below an adult age class (Fig. 3). To describe sexually mature individuals, the term ‘adult’ was used across all papers however, ‘mature’ (Plowright et al. 2008) and ‘aged’ (Breed et al. 2011) were used in addition to ‘adult’ to describe an adult class beyond 8 years of age in two of the studies.

Age classifications baby, infant, pup, young, juvenile, non-volant young, volant young, pubertal, sub-adult, pre-breeding, mature, adult and aged by species and age in months based on 24 different sources (Nelson 1965; O’Brien et al. 1996, 2003; Vardon and Tidemann 1999, 2000; Holmes 2002; Welbergen 2006, 2010; Plowright et al. 2008; Breed et al. 2011; Tidemann and Nelson 2011; Edson et al. 2015, 2019; McMichael et al. 2015; Todd et al. 2018; Barrett et al. 2020; Irving et al. 2020; Pinson 2022; Woon et al. 2020; BatOneHealth 2021; Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 2022). Some articles assigned chronological age to described classes but did not differentiate between species covered in the paper. They are shown as species groups. The distinction between sub-adult and adult is determined on sexual maturity (based on visual characteristics). Grey bars represent gaps in age classes that were not defined by the authors. Coloured circles next to the source represents its discipline. ND, not determined.

Less frequently, individuals were assigned to one of two age classes, for example, either juvenile and adult or sub-adult and adult whereas others split them into additional age cohorts with 4 or 5 age classes such as baby, juvenile, sub-adult and adult (Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 2022) or 0–1 month, 3 months, 6 months, pre-breeding and mature (Plowright et al. 2008). Of the 36 sources that used age classes, the most common combination after juvenile, sub-adult and adult (n = 9) was simply juvenile and adult (n = 6).

Even commonly used age class terms had substantial differences in the assumed chronological age cut-offs (Fig. 3). The term ‘young’ varied from representing an individual from 0–12 months to 0–24 months of age. The common term ‘juvenile’ characterised an individual as young as 0–3 months to as old as 3–18 months. Similarly, the term sub-adult was applied to individuals presumed to range from 3 months to 3 years. The variation between sub-adult and adult is often distinguished from observable sexual maturity. However, this was interpreted as occurring in females at 18 months, 2 years or 3 years, depending on the source.

Metrics used to assess biological age class

A common approach to estimate biological age class of flying-foxes was to use a combination of morphometrics (e.g. based on forearm length and body mass) and development of reproductive characteristics (e.g. testicle and penis size for males and nipple development for females, 30%; Table 1). Since reproduction is highly seasonal, some papers additionally included an estimation of commencement of annual birth pulses to create an approximation of chronological age or to support the choice of age classification (Vardon and Tidemann 1998; Plowright et al. 2008; Tidemann and Nelson 2011). Out of the 34 articles that mention morphometrics as an indicator of age, 70% (n = 23) did not explicitly state what criteria were used.

| Reference | Species | Sex | Age classification | Forearm (mm) | Weight (g) | Reproductive considerations mentioned | Tooth considerations mentioned | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grey literature | ||||||||

| BatOneHealth (2021) | P. alecto and P. poliocephalus | Not mentioned | Juvenile | 150 | <450 | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Yes – tooth wear considered, but not a primary determinant | |

| Sub-adult | 150–160 | 450–550 | ||||||

| Adult | >160 | >550 | ||||||

| Pinson (2022) | P. alecto and P. poliocephalus | Male | Premmie | <57 | <70 | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Yes – tooth wear considered until 7 years of age, but not a primary determinant | |

| Baby | >57 | >70 | ||||||

| Juvenile | 130–150 | 250–400 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 145–155 | 400–600 | ||||||

| Adult | >160 | 600–1100 | ||||||

| Female | Premmie | <57 | <70 | |||||

| Baby | >57 | >70 | ||||||

| Juvenile | 130–150 | 250–400 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 140–150 | 400–500 | ||||||

| Adult | >155 | 500–1100 | ||||||

| Tolga Bat Hospital (J. Mclean, pers. comm., 2022) | P. conspicillatus | Not mentioned | Juvenile | 135–160 | Not mentioned | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Not mentioned | |

| Sub-adult | >160 | |||||||

| Adult | >165 | |||||||

| Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland (D. Wade, pers. comm., 2022) | P. alecto and P. poliocephalus | Male | Baby | <130 | <350 | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Yes – presence of milk teeth. | |

| Juvenile | 130–150 | <500 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 145–160 | <600 | ||||||

| Adult | >160 | >600 | ||||||

| Female | Baby | <130 | <350 | |||||

| Juvenile | 130–145 | <450 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 145–160 | <600 | ||||||

| Adult | >160 | >600 | ||||||

| WIRES (S. Stanford, pers. comm., 2023) | P. alecto and P. poliocephalus | Not mentioned | Pup | Follow Flying-fox Milk Chart | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Yes – tooth wear and discolouration considered. | ||

| Juvenile | <150 | <500 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | Over 50% of adult weight and size | |||||||

| Adult | Not mentioned | |||||||

| Linda Collins, pers. comm., 2023 | P. alecto and P. poliocephalus | Male | Young | <128 | Not reliable | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Yes – tooth development considered until all incisors erupted (10 weeks). | |

| Juvenile | 128–150 | <500 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 148–160 | <600 | ||||||

| Adult | >160 | >600 | ||||||

| Female | Young | <128 | Not reliable | |||||

| Juvenile | 128–148 | <400 | ||||||

| Sub-adult | 145–155 | <550 | ||||||

| Adult | >155 | Refer to reproductive considerations | ||||||

| P. scapulatus | Insufficient data | Young | Insufficient data | Not mentioned | ||||

| Juvenile | ||||||||

| Sub-adult | >125 | |||||||

| Adult | ||||||||

| WIRES (L. Ruytenberg, pers. comm., 2023) | P. alecto, P. scapulatus and P. poliocephalus | Yes – males heavier in mating season | Baby | Follow Pinson Flying-Fox Ageing guide | Yes – primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | No – tooth methods avoided | ||

| Juvenile | ||||||||

| Adult | ||||||||

| Peer-reviewed literature | ||||||||

| Hall (1987) | P. alecto | Male | Adult | 145–182 | 340–700 | Not mentioned | ||

| Female | 138–175 | 280–650 | ||||||

| P. poliocephalus | Male | Adult | 144–164 | 500–1050 | ||||

| Female | 138–160 | 460–800 | ||||||

| P. conspicillatus | Not mentioned | Adult | 155–175 | 350–600 | ||||

| P. scapulatus | Not mentioned | Adult | 118–143 | 200–600 | ||||

| Holmes (2002) | P. poliocephalus | Not mentioned | Juvenile | 60–130 | 50–600 | Yes – Primary determinant in conjunction with morphology | Not mentioned | |

| Sub-adult | 120–160 | 500–700 | ||||||

| Adult | 150–180 | 600–1000 | ||||||

| Luly et al. (2015) | P. alecto | Not mentioned | Juvenile | <140 | <500 | Not mentioned | No – discolouration and tooth wear assessment – deemed unlikely to be useful | |

| Adult | >140 | >500 | ||||||

| Mclean et al. (2019) | P. conspicillatus | Not mentioned | Juvenile | <150 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | |

| Adult | >150 | |||||||

| Vardon and Tidemann (2000) | P. alecto | Not mentioned | Juvenile | <170 | Not mentioned | Yes | Not mentioned | |

| Adult | >170 | |||||||

| Books (identification guides) | ||||||||

| Churchill (2008) | P. alecto | Not mentioned | Adult | 153–191 | 590–880 | Yes – mentioned in ageing section of field guide | Yes – tooth wear mentioned in ageing section of field guide | |

| P. poliocephalus | Adult | 151.6–177.0 | 410–1270 | |||||

| P. conspicillatus | Adult | 150–183 | 380–950 | |||||

| P. natalis | Adult | 110–140 | 220–500 | |||||

| P. scapulatus | Adult | 116.3–140 | 258–500 | |||||

| Hall and Richards (2000) | P. alecto | Not mentioned | Adult | 150–190 | 500–1000 | Not mentioned – no ageing section in field guide | ||

| P. poliocephalus | Adult | 140–175 | 600–1000 | |||||

| P. conspicillatus | Adult | 155–180 | 500–1000 | |||||

| P. scapulatus | Adult | 125–155 | 300–600 | |||||

Note: those with multiple species listed in the species column did not separate which species the reference ranges applied to. Those with only one class are average sizes described by the authors for adults. Reproductive considerations include observation of sexually mature features such as descended testes, evidence of lactation, pregnancy and attached young.

Morphometric descriptions of adult flying-foxes were relatively consistent for P. alecto, P. poliocephalus and P. conspicillatus; with a minimum of ~150 mm in forearm length and ~500 g of body weight (if considered). Adult P. scapulatus are smaller, with a minimum forearm length of 116–125 mm and a minimum weight of either 200 g (Hall 1987), 258 g (Churchill 2008) or 300 g (Hall and Richards 2000) depending on the source. Some studies used a single set of morphological cut-offs for both sexes, whereas others applied distinct cut-offs for each sex. Occasionally, ranges were non-overlapping. For example, adult female P. poliocephalus could have a forearm length of 138–160 mm (Hall 1987) v. >160 mm (Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 2022; Pinson 2022). Immature (non-adult) age classes varied substantially, and are largely dependent on the number of non-adult age classes used. If cut-offs are compared based on just terminology, a juvenile P. conspicillatus could be either up to 150 mm or between 135 and 160 mm in forearm and a male P. alecto with a forearm length of 149 mm could be classified as either a juvenile, subadult or adult, though combined assessments of forearm length and weight resolves some ambiguity (Table 1). One study defined the method for forearm measurement as the measurement of the length of the radius (maximal distance from olecranon process of the ulna to the flexed carpus) when the bats wing is folded and is generally measured with callipers (Plowright et al. 2008).

In addition to morphometrics, many studies (n = 14) used complementary measures to assist with classifying bats into age groups, some of which are more quantifiable than others. General impressions on the body size and form of the individual flying-fox, along with the eyes, ears and shoulders were mentioned as a means to distinguish non-adult bats from adults. The development of fur covering and teeth were mentioned as a means to identify various ages of dependent young (Linda Collins, pers. comm., October, 2023). The time of year relative to the breeding and birthing seasons was also identified as a contributor to age assessments, and less frequently, the presence of scarring of the wings and ears, colouring of the fur and shape and presence of cartilage of the wing joint. These additional measures are noted in the ‘other’ column in Table S1. The interpubic distance (i.e. the distance between the two pubic bones in the pelvic girdle) was also proposed as a measure to estimate age class as it is correlated to forearm length (Chapman et al. 1994).

Reproductive maturity was a critical diagnostic tool for determining the adult age class and was assessed similarly across sources. For females, sexual maturity was determined based on pregnancy, the expression of milk from the nipples or the presence of worn or elongated nipples that were assumed to represent past nursing. For males, sexual maturity was generally determined based on a subjectively larger penis and testes. Reproductive male genitals were quantifiably described in only three cases. P. alecto and P. poliocephalus mature males were described as having testes descended and larger than 10 mm in diameter (Welbergen 2010; BatOneHealth 2021) and P. scapulatus, having a penis of ~5 mm wide (Collins 2002). Under non-invasive instances, this can be a challenging measure as Pteropid bats have been observed to have the capacity to internally retract their testes (Nelson 1963). The presence of barbules on the ventral aspect of the glans penis has been noted to only appear in sexually mature males (Jonathan H. Epstein, EcoHealth Alliance, New York, NY, pers. comm., September, 2023) however, was not included in the methods descriptions of any of the sources included here. Despite early studies describing sex-based morphometric differences (Hall 1987; Chapman et al. 1994; McNab and Armstrong 2001; Welbergen 2010), only five articles described different morphometric cut-offs based on sex of the animal (Table 1).

Non-invasive classification of age in flying-foxes inherently involves subjectivity and imprecision. Sources acknowledged this by the use of phrases such as ‘around’, ‘taking into account’, ‘with the assumption’ or ‘approximately,’ implying an awareness of the inherent variability in ageing indicators, and occasionally, by using an approach that encompassed multiple morphological traits to form a holistic impression of an animal’s age. Some studies explicitly acknowledged these limitations by highlighting that specific age classes may be underestimated (Todd et al. 2018) or providing direct disclaimer statements indicating use as a guide (Linda Collins, BatOneHealth, Pinson, and Biolac Flying Fox Milk Formula). Such language accounts for the existence of ambiguous cases where individuals with observed development (or lack of development) of sexual characteristics may fall outside the expected morphological range, such as ‘small’ reproductively active adults or ‘large’ pre-reproductive sub-adults.

Discussion

Understanding age-related patterns and processes in wildlife populations can inform conservation strategies, assist with population management, and advance our understanding of the ecology and evolution of wildlife species. Age classes are a subjective and context-dependent construct, as demonstrated by the few sources in this literature review describing age in the same manner. This likely arises from the fundamental challenges presented by applying categorical demarcations (biological age classes) to an otherwise continuous process (chronological ageing), and the difficulties in accounting for individual variation in size and growth rates in diverse wild populations. We show that peer-reviewed and grey literature present large variations in approaches to ageing flying-foxes – from the terms used to identify biological age classes, what features define them and how they are described. This variability limits cross-study comparison, and ultimately affects the accuracy and reliability of age-related research and management decisions. Below, we first address the underlying fundamental challenges identified (disciplinary context, diagnostic sensitivity and individual and interannual variability), and then address how these can be used to guide procedural improvements to better allow cross-study comparisons.

This paper addresses the fundamental question of what a ‘sub-adult’ and ‘adult’ mean in a biological context. Although sexual maturity is often used to distinguish these classes, this may oversimplify the transition to physiological capability for reproduction v. successful reproduction. Female flying-foxes can physiologically reproduce in their second year, but estimates of the proportion that successfully do so have relied on morphometric estimates of age, introducing significant uncertainty. Similarly, males flying-foxes may face additional social barriers to reproduction despite physiological maturity. Neither of these affects their true chronological age. Fundamentally, age classes are biologically meaningful categories that differentiate individuals across important life stages, yet what comprises an important life stage is context-dependent across studies. A disease ecologist modelling viral transmission dynamics, for example, may find it more sensible to create cut-offs based on factors that would influence the spread and maintenance of a virus, such as age-varying contact rates, or by immune system development and the presence of maternally derived antibodies (Peel et al. 2018; Edson et al. 2019; Jeong and McCallum 2021). A population ecologist wanting to model population structure and viability may consider age classes that separate individuals based on age-dependent mortality rates (e.g. when gaining independence), or reproductive capacity, to provide insights into population recruitment and viability (Vardon and Tidemann 2000; McIlwee and Martin 2002; Fox et al. 2008; Tidemann and Nelson 2011). In the area of wildlife care, these age class differentiations take on practical significance. For instance, rehabilitators often employ distinctions among younger stages of animal development, particularly in puppyhood, to tailor appropriate care routines. This includes determining suitable food volumes and cage companions, as well as monitoring growth during care. Although many care groups differentiate these stages into weeks of age, this varies among organisations (Jennefer Mclean, Tolga Bat Hospital, Atherton, Qld, pers. comm., July, 2023). Although the use of age class categories is pragmatic, the variability of terms used (i.e. whether a 6-month-old individual is called an ‘infant’, ‘baby’, ‘pup’, ‘juvenile’, ‘volant young’, ‘pre-breeding’ or ‘subadult’) and misalignment of categorical demarcations among different user groups (i.e. whether a sub-adult ranges from 3–24 months, 6–12 months or 12–24 months; Fig. 3) limits cross-study comparison and multidisciplinary analyses.

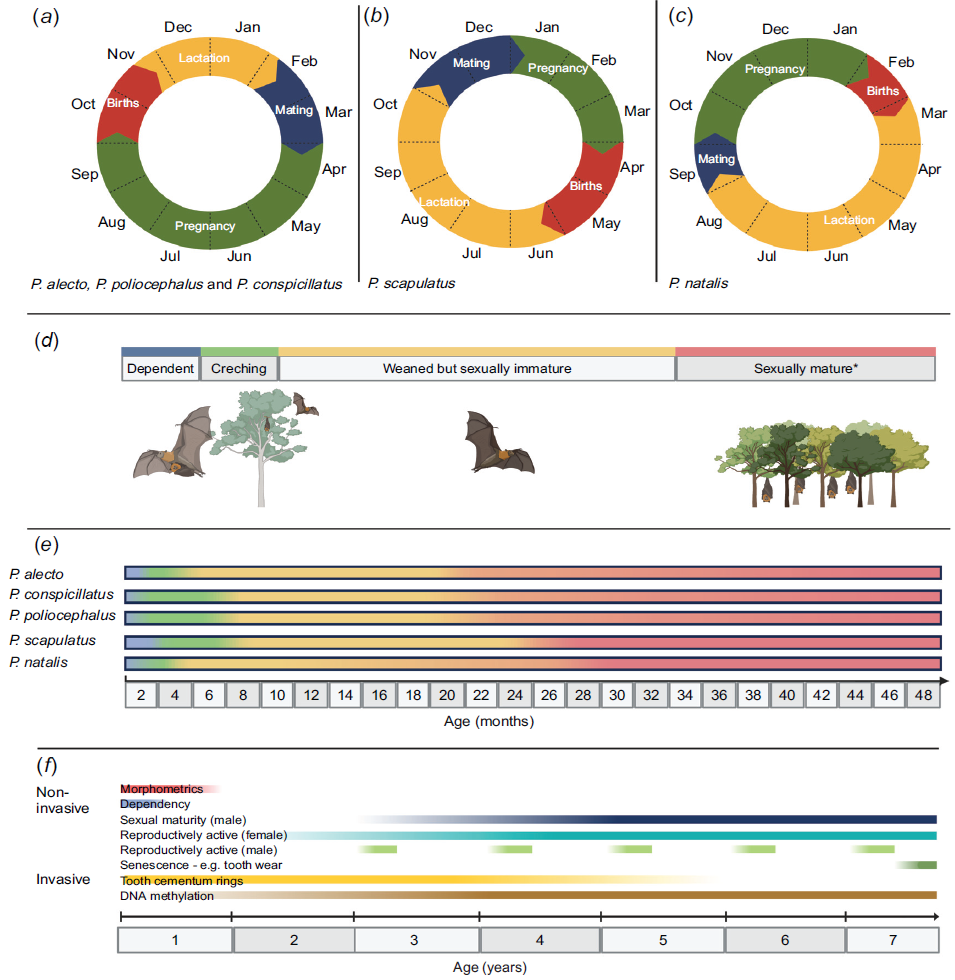

Even if age classes could be defined that are biologically meaningful across disciplines, they can be challenging to differentiate non-invasively in practice. As an individual ages, multiple concurrent and partially overlapping process occur: each individual initially grows rapidly and then plateaus; transitions from being dependent to independent; becomes sexually mature, reproduces and then senesces. As a result, the diagnostic capacity of morphometrics, reproductive characteristics and other complementary measures for determining age class varies across an individual’s life span (Fig. 4). For example, rapid growth and permanent tooth eruption patterns in the first 3–4 months of life allows wildlife rehabilitators to undertake fine-scale estimation of age in dependent pups in weeks or days (Brunet-Rossinni and Austad 2004; Divljan et al. 2011; Parry-Jones 2011; Todd et al. 2018), whereas development of external sexual characteristics allows only coarse demarcation between sub-adults and sexually mature adults. Slow asymptotic growth rates have been reported (Brunet-Rossinni and Austad 2004; Parry-Jones 2011), but are uninformative in determining age.

Biological growth and seasonal life stage timelines for flying-foxes. The data for seasonal life stages for P. alecto, P. poliocephalus, P. conspicillatus and P. scapulatus are extracted from the Department of Environment and Science (2020), and for P. natalis from the Department of Climate, Change Energy, the Environment and Water (2008). The data for biological stages are compiled from the documents previously mentioned in addition to ‘Australian bats’, by Churchill (2008), and journal articles, Fox (2006), Martin and McIlwee (2002) and Todd et al. (2018). Seasonal life stages of (a) P. alecto, P. poliocephalus, P. conspicillatus, (b) P. scapulatus and (c) P. natalis illustrate approximate mating periods followed by 6-month gestation (5 months for P. natalis), approximate birthing periods and lactation. Section (d) is an illustration of the different biological life stages of a flying-fox. Timeline (e) represents the duration of biological stages of each species of flying-fox after birth in months. The representation of the colours matches those from section (d). (f) displays the usefulness of non-invasive and invasive ageing techniques as individuals age. Note: an asterisk (*) represents that sexual maturity is reached at different ages for males and females. These timelines can vary by geographic region particularly for P. alecto whose birthing window can occur in January–March in the Northern Territory (Vardon and Tidemann 1998, 2000) but generally follow the same duration of each phase. Created with BioRender.com.

The highly seasonal nature of flying-fox births creates distinct age cohorts (Fig. 4; Nelson 1965; McIlwee and Martin 2002) and can assist in assigning age classes and estimated birth years (Edson et al. 2019). However, as cohorts get older, distinguishing between them can become more difficult (Edson et al. 2019). Individuals at the boundaries of age classes have the highest likelihood of being misclassified, particularly where the diagnostic criteria are weak (e.g. morphology can be insensitive in differentiating older ‘juvenile’ flying-foxes (e.g. ~10–12 months) from pre-breeding subadults from the previous birth cohort (~22–24 months) at a time when neither have developed external characteristics of sexual maturity). Additionally, significant inter-individual variation in physical development and reproductive maturity exists within birth cohorts, due to intrinsic factors such as hereditary genetics and maternal condition (Parry-Jones 2011) or extrinsic factors, such as interannual or inter-individual differences in resource availability and nutritional composition (Welbergen 2010; Parry-Jones 2011). This within-cohort variation means that prescriptive cut-offs at these boundaries are somewhat arbitrary. For instance, pups of known age (those with their umbilical cords still attached), exhibit substantial weight and forearm variations (Kerryn A. Parry-Jones, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, pers. comm., August, 2023; Lib Ruytenberg, WIRES, Lismore, NSW, pers. comm., August, 2023). Moreover, morphological and growth difference have been noted between young that have been reared by their mothers than those hand-reared (Jennefer Mclean, Tolga Bat Hospital, Atherton, Qld, pers. comm., July, 2023; Lib Ruytenberg, WIRES, Lismore, NSW, pers. comm., August, 2023), presenting difficulties in ageing wild-born mother-reared pups after 8 weeks of age (Linda Collins, pers. comm., November, 2021). However, differences in growth between the sexes do not appear before 4 months of age, with only marginal changes becoming apparent by ~6 months of age (Linda Collins, pers. comm., November, 2021).

Intrinsic and extrinsic sources of variability are also ubiquitous in natural populations but are challenging to identify. For example, classifying first-time female breeders can be challenging before pregnancy is palpable, especially as females smaller than ‘typical’ adult size (e.g. <160-mm forearm length) are capable of conceiving (Vardon and Tidemann 1998) and sexually mature adults who miscarried during their first pregnancy would not exhibit nipple wear from suckling (Todd et al. 2018). Environmental conditions can further complicate age assessments that rely on physical characteristics. Tooth wear patterns may vary with diet across different geographic regions or seasons, potentially confounding tooth-based ageing methods. Similarly, body mass-based classifications may be unreliable during period of food scarcity when individuals are nutritionally stressed and underweight. Poor resources during their primary growth period may also lead to overall small adult sizes and delays in reproduction. These environmental influences create additional challenges for consistent age classification across studies conducted in different regions or seasons. As a result of these fundamental challenges, we found that many studies used a pragmatic approach – where a holistic consideration of combination of features (most commonly forearm length, body weight, and assessment of sexual maturity), combined with prior knowledge and experience, was used to subjectively assign the most likely age class, rather than rigidly adhering to established thresholds. This is analogous to a Bayesian modelling approach, where multiple input datasets, including physical measurements and observational data, are used as priors to make probabilistic predictions of age (D. H. Kerlin, S. J. Low Choy, M. Ruiz-Aravena, D. G. Hamilton, S. Comte, H. I. McCallum, A. Storfer, P. A. Hohenlohe, R. K. Hamede and M. E. Jones, unpubl. data).

Many of the fundamental challenges of assigning age classes to flying-foxes are difficult to resolve in the field, yet recent advances in modelling and molecular techniques for age determination hold promise for overcoming some of these challenges. While these methods continue to be developed, it is important to establish best practices to improve consistency and comparability in age assignments across different studies and facilitate meaningful comparisons and synthesis of findings. Below, we make four recommendations towards this goal and provide a summary of characteristics used to estimate age in Fig. S2.

Recommendation 1: clearly define age class terminology

One of the major challenges identified in this review was the ambiguity of age classifications used across studies. Out of 359 articles screened, 48 articles estimating age (11 omitted from initial search, 14 without references and 23 that did not describe method criteria) did not describe ageing methods in a way that could be replicated, compromising critical assessment of the results and future cross-study comparison or meta-analyses. The remaining studies defined age classes by their chronological interpretation (e.g. that juveniles were assumed to be <12 months) or by the cut-offs used (e.g. juveniles are sexually immature and have forearms and weights below a certain threshold), but few studies included both. The substantial differences in the chronological age cut-offs and morphological cut-offs for each term means that studies become incomparable without clear definitions.

We recommend that, at a minimum, publications clearly define the age classes used within the main text, including the assumed chronological age and any morphological features and cut-offs used to assign individuals to age classes. Ideally, this should use the same terminology as an existing publication, and that publication cited. Where new terminology, definitions or cut-offs are introduced, justifications should be provided. Relative terms such as ‘smaller’ and ‘larger’ should be avoided unless accompanied by expected morphological ranges or cut-offs, relative to the time of year where relevant. Optionally, photographs and more detailed descriptions and metadata (including the timing of seasonal births or other seasonal events that contribute to age determination) could be provided within supplementary material to facilitate consistency across studies.

Recommendation 2: identify species and sex differences

Across the studies in our review, flying-fox species and sex were inconsistently accounted for. P. alecto, P. poliocephalus and P. conspicillatus are closely related species (Tidemann and Nelson 2011) and often studied under the same ageing methods, yet some studies have identified different sizes at full development (Hall and Richards 2000). Morphometric differences have been identified between male and female flying-foxes, however this was frequently not accounted for in age-based cut-offs. For example, significant dimorphism and bimaturation is present in wild P. poliocephalus, where adult males are generally heavier than adult females outside of breeding season (Hall and Richards 2000; Welbergen 2010), and up to 40% heavier than adult females at the start of the breeding season (Welbergen 2010). This difference was noted in some sources (e.g. Vardon and Tidemann 1998, Pinson 2022; Table 1). Although males have shown slower rates of growth than females in some circumstances (Welbergen 2010), other studies have identified that the rate of post-natal growth does not differ between males and females (Nelson 1965; Parry-Jones 2011).

We recommend that studies take into consideration existing data on species- and sex-based differences in morphometrics and reproductive maturity. If such data are unavailable, studies should report their own objective observations. In addition, we recommend that publications should explicitly state whether such differences were taken into account in assigning age classes.

Recommendation 3: provide open access data

By making data openly accessible, researchers can further promote transparency, reproducibility, collaboration, and facilitate meta-analyses and cross-study comparisons. This allows for the identification of variations in age-related patterns across populations, species, climates or time periods that may not be visible in individual studies. Furthermore, the open sharing of data can support the development of novel comprehensive methods such as Bayesian approaches. By accounting for the uncertainty and subjectivity associated with existing metrics, these approaches can significantly enhance the accuracy and reliability of individual age assignments (Schwarz and Runge 2009; D. H. Kerlin et al., unpubl. data), better inform our understanding of the influence of individual, species, sex and morphometric variability on age classifications, and improve overall age estimation accuracy.

We recommend that studies include a supplementary table, supplementary dataset or standalone open access dataset that provides the sampling date for each individual, along with their assigned age class, morphometric data and any other complementary data used to assign age. This should be combined with information on the timing of seasonal births or other seasonal events that contribute to age determination.

Recommendation 4: archive tissue samples (where feasible)

DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification that changes with age and can serve as a molecular marker for estimating age in wildlife populations. Recent studies have shown that DNA methylation patterns can be used to accurately estimate age in bats, providing a minimally invasive and reliable method for age determination (Wilkinson et al. 2021). These approaches are currently expensive, but are under ongoing development, and likely to become more accessible in the future, with the potential to be applied retrospectively to archived samples to provide key insights at a finer scale than broad age classes currently allow.

Where feasible, we recommend consideration of archiving tissue samples (such as wing punches in ethanol, or frozen blood cells or buccal swabs) from each individual, to allow later epigenetic ageing to be performed. This is particularly important for studies that include known-aged individuals.

In conclusion, age classifications are a subjective construct that aim to identify individuals at similar, biologically meaningful life stages, when precise chronological age is unknown. However, age class determination presents significant challenges. Across the sources reviewed here, we identified significant variability within terminology, the number of classes, chronological age representation and the use of morphometrics to define classes. Future methodological developments are likely to move away from strict cut-offs, which poorly account for intrinsic and extrinsic variability in growth and development. Additional studies assessing empirical data through mathematical modelling may elucidate the influence and predictive power of the variables discussed. In the meantime, our recommendations can help address these challenges and improve clarity about age-class assignment in flying-foxes and aid future cross-study comparisons.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere thanks to Lee McMichael, John Martin, Hume Field, Justin Welbergen and Jon Epstein for generously sharing insights gained from their flying-fox research endeavours. Furthermore, we are deeply grateful to Storm Stanford, Lib Ruytenberg, Kerryn Parry-Jones, Denise Wade, Dave Pinson and Linda Collins for their invaluable contributions regarding the development of flying-foxes in care.

References

Barrett J, Höger A, Agnihotri K, Oakey J, Skerratt LF, Field HE, Meers J, Smith C (2020) An unprecedented cluster of Australian bat lyssavirus in Pteropus conspicillatus indicates pre-flight flying fox pups are at risk of mass infection. Zoonoses Public Health 67(4), 435-442.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Breed AC, Breed MF, Meers J, Field HE (2011) Evidence of endemic hendra virus infection in flying-foxes (Pteropus conspicillatus) – implications for disease risk management. PLoS ONE 6(12), e28816.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brook CE, Ranaivoson HC, Andriafidison D, Ralisata M, Razafimanahaka J, Héraud J-M, Dobson AP, Metcalf CJ (2019) Population trends for two Malagasy fruit bats. Biological Conservation 234, 165-171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brunet-Rossinni AK, Austad SN (2004) Ageing studies on bats: a review. Biogerontology 5(4), 211-222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chapman A, Hall LS, Bennett MB (1994) Sexual dimorphism in the pelvic girdle of Australian flying foxes. Australian Journal of Zoology 42(2), 261-265.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cohen AA (2018) Aging across the tree of life: the importance of a comparative perspective for the use of animal models in aging. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 1864(9 Part A), 2680-2689.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cool SM, Bennet MB, Romaniuk K (1994) Age estimation of pteropodid bats (Megachiroptera) from hard tissue parameters. Wildlife Research 21(3), 353-363.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2008) Advice to the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendment to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). (Australian Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia) Avaiable at https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/env/pages/7df9ba95-9910-4d77-9308-6f5ee5a66a49/files/64801-listing-advice.pdf

Divljan A, Parry-Jones K, Wardle GM (2006) Age determination in the grey-headed flying fox. Journal of Wildlife Management 70(2), 607-611.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Divljan A, Parry-Jones K, Wardle GM (2011) One hundred and forty days in the life of a flying-fox tooth-fairy: estimating the age of pups using tooth eruption and replacement. In ‘The biology and conservation of Australasian bats’. (Eds B Law, P Eby, D Lunney, L Lumsden) pp. 97–105. (Royal Zoological Society of NSW: Sydney, NSW, Australia)

Eby P, Peel AJ, Hoegh A, Madden W, Giles JR, Hudson PJ, Plowright RK (2023) Pathogen spillover driven by rapid changes in bat ecology. Nature 613, 340-344.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Edson D, Field H, McMichael L, Vidgen M, Goldspink L, Broos A, Melville D, Kristoffersen J, de Jong C, McLaughlin A, Davis R, Kung N, Jordan D, Kirkland P, Smith C (2015) Routes of hendra virus excretion in naturally infected flying-foxes: implications for viral transmission and spillover risk. PLoS ONE 10(10), e0140670.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Edson D, Peel AJ, Huth L, Mayer DG, Vidgen ME, McMichael L, Broos A, Melville D, Kristoffersen J, de Jong C, McLaughlin A, Field HE (2019) Time of year, age class and body condition predict Hendra virus infection in Australian black flying foxes (Pteropus alecto). Epidemiology and Infection 147, e240.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Epstein JH, Prakash V, Smith C, Daszak P, McLaughlin AB, Meehan G, Field HE, Cunningham AA (2008) Henipavirus infection in Fruit Bats (Pteropus giganteus), India. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(8), 1309-1311.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fancy SG (1980) Preparation of mammalian teeth for age determination by cementum layers: a review. Wildlife Society Bulletin 8(3), 242-248.

| Google Scholar |

Fox S (2006) Population structure in the spectacled flying fox, Pteropus conspicillatus: a study of genetic and demographic factors. PhD thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia. Available at https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/8053/

Fox S, Luly J, Mitchell C, Maclean J, Westcott DA (2008) Demographic indications of decline in the spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus) on the Atherton Tablelands of northern Queensland. Wildlife Research 35(5), 417-424.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gonzale E, Close R (1999) The maternal behaviour and development of a little red flying-fox Pteropus scapulatus in captivity. Australian Zoologist 31(1), 175-180.

| Google Scholar |

Gonzáles-Suárez M, Gomez A, Revilla E (2013) Which intrinsic traits predict vulnerability to extinction depends on the actual threatening processes. Ecosphere 4(6), 76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hall LS (1987) Identification, distribution and taxonomy of Australian flying-foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae). Australian Mammalogy 10, 75-79.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayman DTS, Peel AJ (2016) Can survival analyses detect hunting pressure in a highly connected species? Lessons from straw-coloured fruit bats. Biological Conservation 200, 131-139.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hecht L (2021) The importance of considering age when quantifying wild animals’ welfare. Biological Reviews 96(6), 2602-2616.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Irving AT, Ng JHJ, Boyd V, Dutertre CA, Ginhoux F, Dekkers MH, Meers J, Field HE, Cameri G, Wang LF (2020) Optimizing dissection, sample collection and cell isolation protocols for frugivorous bats. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11, 150-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jackson SJ, Andrews N, Ball D, Bellantuono I, Gray J, Hachoumi L, Holmes A, Latcham J, Petrie A, Potter P, Rice A, Ritchie A, Stewart M, Strepka C, Yeoman M, Chapman K (2016) Does age matter? The impact of rodent age on study outcomes. Laboratory Animals 51(2), 160-169.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jeong J, McCallum H (2021) Effects of waning maternal immunity on infection dynamics in seasonally breeding wildlife. Ecohealth 18(2), 194-203.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kurdyukov S, Bullock M (2016) DNA methylation analysis: choosing the right method. Biology 5(1), 3.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Luly J, Buettner P, Parsons J, Thiriete D, Gyurisa E (2015) Tooth wear, body mass index and management options for edentulous black flying-foxes (Pteropus alecto Gould) in the Townsville district, north Queensland, Australia. Australian Veterinary Journal 93, 84-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Martin L, McIlwee AP (2002) The reproductive biology and intrinsic capacity for increase of the grey-headed flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus (Megachiroptera), and the implications of culling. In ‘Managing the Grey-headed Flying-fox: as a threatened species in NSW’. (Eds P Eby, D Lunney) pp. 91–108. (Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales: Sydney, NSW, Australia)

McGuckin MA, Blackshaw AW (1991) Seasonal changes in testicular size, plasma testosterone concentration and body weight in captive flying foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus and P. scapulatus). Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 92, 339-346.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McIlwee AP, Martin L (2002) On the intrinsic capacity for increase of Australian flying-foxes (Pteropus spp., Megachiroptera). Australian Zoologist The 32(1), 76-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mclean J, Johnson A, Woods D, Muller R, Blair D, Buettner PG (2019) Growth rates of, and milk feeding schedules for, juvenile spectacled flying-foxes (Pteropus conspicillatus) reared for release at a rehabilitation centre in north Queensland, Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology 66(3), 201-213.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McMichael L, Edson D, McLaughlin A, Mayer D, Kopp S, Meers J, Field H (2015) Haematology and plasma biochemistry of wild black flying-foxes, (Pteropus alecto) in Queensland, Australia. PLoS ONE 10(5), e0125741.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McNab BK, Armstrong MI (2001) Sexual dimorphism and scaling of energetics in flying foxes of the genus Pteropus. Journal of Mammology 82(3), 709-720.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mollentze N, Streicker DG (2020) Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117(17), 9423-9430.

| Google Scholar |

Morris P (1972) A review of mammalian age determination methods. Mammal Review 2(3), 69-104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nelson JE (1965) Behaviour of Australian pteropodidae (Megachiroptera). Animal Behaviour 13(4), 544-557.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

O’Brien GM, Curlewis JD, Martin L (1993) Effect of photoperiod on the annual cycle of testis growth in a tropical mammal, the little red flying fox, Pteropus scapulatus. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 98, 121-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

O’Brien GM, Curlewis JD, Martin L (1996) A heterologous assay for measuring prolactin in pituitary extracts and plasma from Australian flying foxes (genus Pteropus). General and Comparative Endocrinology 3(104), 304-311.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

O’Brien GM, McFarlane JR, Kearney PJ (2003) Pituitary content of luteinizing hormone reveals species differences in the reproductive synchrony between males and females in Australian flying-foxes (genus Pteropus). Reproduction Fertility and Development 15(4), 255-261.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Parry-Jones K (2011) “Diverse weights and diverse measures”: factors affecting the post-natal growth of the grey-headed flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus and implications for ageing juvenile flying-foxes. In ‘The biology and conservation of Australasian bats’. (Eds B Law, P Eby, D Lunney, L Lumsden) pp. 175–184. (Royal Zoological Society of NSW: Sydney, NSW, Australia)

Parsons JG, Robson SKA, Shilton LA (2011) Roost fidelity in spectacled flying-foxes Pteropus conspicillatus: implications for conservation and management. In ‘The biology and conservation of Australasian bats’. (Eds B Law, P Eby, D Lunney, L Lumsden) pp. 66–71. (Royal Zoological Society of NSW: Sydney, NSW, Australia)

Peel AJ, Baker KS, Hayman DTS, Suu-Ire R, Breed AC, Gembu G-C, Lembo T, Fernández-Loras A, Sargan DR, Fooks AR, Cunningham AA, Wood JLN (2016) Bat trait, genetic and pathogen data from large-scale investigations of African fruit bats, Eidolon helvum. Scientific Data 3(1), 160049.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peel AJ, Wood JLN, Baker KS, Breed AC, de Carvalho A, Fernández-Loras A, Gabrieli HS, Gembu G-C, Kakengi VA, Kaliba PM, Kityo RM, Lembo T, Mba FE, Ramos D, Rodriguez-Prieto I, Suu-Ire R, Cunningham AA, Hayman DTS (2017) How does africa’s most hunted bat vary across the continent? Population traits of the straw-coloured fruit bat (Eidolon helvu) and its interactions with humans. Acta Chiropterologica 19(1), 77-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peel AJ, Baker KS, Hayman DTS, Broder CC, Cunningham AA, Fooks AR, Garnier R, Wood JLN, Restif O (2018) Support for viral persistence in bats from age-specific serology and models of maternal immunity. Scientific Reports 8(1), 3859.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pierson ED, Rainey WE (1992) The biology of flying foxes of the genus Pteropus: a review. In ‘Pacific Island flying foxes: proceedings of an international conservation conference’, 1–2 February 1990, Honolulu, HI, USA. (Eds DE Wilson, GL Graham) Biological Report 90(23), pp. 1–17. (United States Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, DC, USA) Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA322812.pdf

Plowright RK, Field HE, Smith C, Divljan A, Palmer C, Tabor G, Daszak P, Foley JE (2008) Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London – B. Biological Sciences 275(1636), 861-869.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schwarz LK, Runge MC (2009) Hierarchical Bayesian analysis to incorporate age uncertainty in growth curve analysis and estimates of age from length: Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus) carcasses. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 66(10), 1775-1789.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Southerton SG, Birt P, Porter J, Ford HA (2004) Review of gene movement by bats and birds and its potential significance for eucalypt plantation forestry. Australian Forestry 67(1), 44-53.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Streicker DG, Gilbert AT (2020) Contextualizing bats as viral reservoirs. Science 370(6513), 172-173.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tait J, Perotto-Baldivieso HL, McKeown A, Westcott DA (2014) Are flying-foxes coming to town? Urbanisation of the spectacled flying-fox (Pteropus conspicillatus) in Australia. PLoS ONE 9(10), e109810.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tidemann CR, Nelson JE (2011) Life expectancy, causes of death and movements of the grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) inferred from banding. Acta Chiropterologica 13(2), 419-429.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Todd CM, Westcott DA, Rose K, Martin JM, Welbergen JA (2018) Slow growth and delayed maturation in a Critically Endangered insular flying fox (Pteropus natalis). Journal of Mammalogy 99(6), 1510-1521.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Vardon MJ, Tidemann CR (1998) Reproduction, growth and maturity in the black flying-fox, Pteropus alecto (Megachiroptera : Pteropodidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 46(4), 329-344.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vardon MJ, Tidemann CR (1999) Flying-foxes (Pteropus alecto and P. scapulatus) in the Darwin region, north Australia: patterns in camp size and structure. Australian Journal of Zoology 47(4), 411-423.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vardon MJ, Tidemann CR (2000) The black flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) in north Australia: juvenile mortality and longevity. Australian Journal of Zoology 48(1), 91-97.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Veiberg V, Nilsen EB, Rolandsen CM, Heim M, Andersen R, Holmstrøm F, Meisingset EL, Solberg EJ (2020) The accuracy and precision of age determination by dental cementum annuli in four northern cervids. European Journal of Wildlife Research 66, 91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Welbergen JA (2006) Timing of the evening emergence from day roosts of the grey-headed flying fox, Pteropus poliocephalus: the effects of predation risk, foraging needs, and social context. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 60(3), 311-322.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Welbergen JA (2010) Growth, bimaturation, and sexual size dimorphism in wild gray-headed flying foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus). Journal of Mammalogy 91(1), 38-47.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilkinson GS, Adams DM, Haghani A, Lu AT, Zoller J, Breeze CE, Arnold BD, Ball HC, Carter GG, Cooper LN, Dechmann DKN, Devanna P, Fasel NJ, Galazyuk AV, Günther L, Hurme E, Jones G, Knörnschild M, Lattenkamp EZ, Li CZ, Mayer F, Reinhardt JA, Medellin RA, Nagy M, Pope B, Power ML, Ransome RD, Teeling EC, Vernes SC, Zamora-Mejías D, Zhang J, Faure PA, Greville LJ, Herrera MLG, Flores-Martínez JJ, Horvath S (2021) DNA methylation predicts age and provides insight into exceptional longevity of bats. Nature Communications 12(1), 1615.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woon AP, Boyd V, Todd S, Smith I, Klein R, Woodhouse BI, Riddell S, Crameri G, Bingham J, Wang LF, Purcell AW, Middleton D, Baker ML (2020) Acute experimental infection of bats and ferrets with Hendra virus: Insights into the early host response of the reservoir host and susceptible model species. PLoS Pathogens 16(3), e1008412.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |