Potential threats and habitat of the night parrot on the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area

C I *

C I * A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

Abstract

The Endangered night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) is one of the rarest birds in Australia, with fewer than 20 known to occur in Queensland and, prior to 2020, only occasional detections from a handful of sites in Western Australia (WA). Here, we provide an introduction to night parrots on the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) in WA from the perspectives of both Indigenous rangers and scientists working together to understand their ecology.

We aimed to identify night parrot sites on the Ngururrpa IPA, compare habitat and likely threats with those in Queensland and identify appropriate management practices.

Between 2020 and 2023, we used songmeters (a type of acoustic recorder) to survey for the presence of night parrots at 31 sites (>2 km apart). At sites where parrots were detected, we used camera-traps to survey predators and collected predator scats for dietary analysis. Forty years of Landsat images were examined to assess the threat of fire to roosting habitat.

Night parrots were detected at 17 of the 31 sites surveyed on the Ngururrpa IPA. Positive detections were within an area that spanned 160 km from north to south and 90 km from east to west. Ten roosting areas were identified, and these occurred in habitat supporting the same species of spinifex (lanu lanu or bull spinifex, Triodia longiceps) used for roosting in Queensland. However, the surrounding landscapes differ in their vegetation types and inherent flammability, indicating that fire is likely to be a more significant threat to night parrots in the Great Sandy Desert than in Queensland. Dingoes (Canis dingo) were the predator species detected most frequently in night parrot roosting habitat and the feral cat was found to be a staple prey for dingoes at night parrot sites.

Our surveys indicated that there could be at least 50 night parrots on the Ngururrpa IPA, which is the largest known population in the world. Fire is a key threat to roosting habitat, occurring in the surrounding sandplain country every 6–10 years. Dingoes are common in night parrot habitat and regularly eat feral cats, which are only occasionally detected in roosting habitat.

We recommend management that focuses on strategic burning to reduce fuel loads in the surrounding landscape, and limiting predator control to methods that do not harm dingoes.

Keywords: applied ecology, conservation biology, conservation management, cross-cultural research, natural resources management, threatened species.

| Short summary and translation |

| This paper provides an introduction to night parrots in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia from the dual perspectives of Indigenous rangers and scientists working together to understand their ecology on the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area. We describe night parrot roosting habitat and use firescar mapping and predator surveys to develop recommendations for the protection of night parrots in this area. |

| Kukatja summary: Ngatjangkura inni kulu kulkurru ngaka ngurrupa IPA. Rangers kamu scientists paya warakuyarra kutjungka tjatuwana mangininpa. Kulkurruya Ngurra tjanapa nginaya mangalwana. Ngampurrpala tjana kangikuwa warukamarra wilpinpa murtitikirlpaya kamu murtika. |

| A short video describing our project can be seen here. |

Introduction

We the Ngururrpa Rangers have been looking for night parrots since 2019. First we thought they were only living in one area, on our neighbour’s country, but then we started checking in our area and ended up finding evidence that they are here. We are still looking for them, to make sure they are safe, and we are still finding them. [Clifford Sunfly, Ngururrpa ranger]

Nearly half the world’s bird species are in decline (BirdLife International 2022). More than 160 bird species have been lost in the past 500 years, and globally 13% of bird species are currently threatened with extinction. Invasive species have been the major driver of extinctions (Szabo et al. 2012), but the leading causes of bird population declines across the world are agriculture (including transforming habitats, use of machinery and chemicals) and deforestation (BirdLife International 2022). However, climate-change impacts are rapidly accelerating and in Australia the climate-driven threats of drought, fire and heat are believed to have surpassed invasive species to become the leading cause of recent bird population decline (Garnett et al. 2024).

On the Australian mainland, woodland communities have been devastated by clearing and other agricultural practices, and fires remove roosting, nesting and feeding resources (Ensbey et al. 2023). Cats (Felis catus) and European foxes (Vulpes vulpes) continue to wreak havoc on ground-nesting and ground-feeding species (Woinarski et al. 2017, 2022).

Fortunately, there remain large areas of Australia that have never been subject to vegetation clearance or agricultural use. Much of this country is under the stewardship of Indigenous Traditional Owners. Areas under Indigenous management, with low human pressure, are critical to the maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem services (O’Bryan et al. 2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up just 3.8% of the national population (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021), and yet are responsible for the 50% of the national conservation reserve system represented by Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2023). Fifty per cent of threatened vertebrate species in Australia occur in areas where Indigenous people have exclusive land rights and 32% of threatened vertebrate species are being managed on Indigenous lands under conservation co-management agreements (Renwick et al. 2017). Indigenous rangers are involved in projects to survey or manage 31% of threatened bird species in Australia (Leiper et al. 2018) making lands under Indigenous management integral to the protection of Australia’s declining species.

Indigenous rangers are a stable workforce, that have proved resilient and enduring, maintaining long-term management programs (Garnett et al. 2018). Indigenous knowledge is alive and well, guiding work programs, informing wildlife surveys, and connecting cultural obligations with land management. A key outcome of these programs has been the reinstatement, or in some cases, maintenance, of traditional Indigenous fire regimes. Broadscale fire management is conducted in many IPAs, reducing the extent of hot summer wildfires and improving the heterogeneity of fire age classes within the landscape (Ruscalleda-Alvarez et al. 2023), which benefits biodiversity (Bliege Bird et al. 2018).

Once distributed throughout Australia’s arid inland, the night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) underwent a significant decline in the late 19th century, which coincided with the arrival of feral predators and the spread of pastoralism (Leseberg et al. 2021a). There were no definite records of the species for more than 100 years until a small population was found in south-western Queensland in 2013 (Pyke and Ehrlich 2014). Night parrots have since been found at about seven locations in central and northern Western Australia, most of which are on Indigenous-managed lands (Lindsay et al., this issue). The known Australia-wide population is fewer than 100 birds, and the species is classified as Endangered under Commonwealth legislation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, see https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2014C00506), with a recent recommendation to uplist to Critically Endangered (Leseberg et al. 2021b).

Although the small population of night parrots in Queensland has been well studied over the past 10 years (Murphy et al. 2017a, 2017b, 2018; Leseberg et al. 2019, 2022) little information has been published about night parrots in Western Australia, where records are scattered across a large area of desert country. Here, Indigenous rangers have used their knowledge of habitats to choose survey areas and have discovered the majority of new locations in the state (Lindsay et al., this issue). There is some cultural knowledge of the species, including stories about how difficult the bird is to find, not revealing itself during fires, floods or hailstorms (Geoffrey Stewart, in Olsen 2018). There are also whispered stories about the night parrot’s call, typically heard at night, being used as a warning to children not to stray from the fire as it was the sound of an evil spirit (Anne Ovi, pers. comm., 19 October 2023). A local name for the night parrot in the Great Sandy Desert is listed as Kulkurru in the Kukatja dictionary (Valiquette 1993), but is yet to be confirmed by Traditional Owners. Even where direct knowledge of night parrots is scant, there is great depth of knowledge of the bird’s habitats and how to manage them, including the distribution of long-unburnt spinifex required for roosting and breeding, and seed and water resources required for foraging.

Why the night parrot has managed to persist in a few very limited locations has been the subject of previous research in Queensland. Murphy et al. (2018) concluded that a combination of low predation pressure from non-native predators (owing to absence of foxes and low prevalence of cats, perhaps owing to the presence of dingoes), long-term stable availability of mature spinifex because of absence of large fires, and a productive landscape that has had only moderate levels of grazing pressure may explain why night parrots have been able to persist in south-western Queensland.

Here, we describe the similarities and differences in habitat and likely threats between the location where night parrots have been found in Queensland, and where the birds have been found on country under the stewardship of the Ngururrpa rangers in the northern Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia. We provide an introduction to current knowledge about night parrot habitat and threats in this area from the dual perspectives of Indigenous rangers and scientists working together to understand the ecology of night parrots on the Ngururrpa IPA. On the basis of the model of Murphy et al. (2018), we predict that wildfire will not be a feature of the habitat where night parrots roost, dingoes will be the dominant predatory species with a low prevalence of cats and an absence of foxes, and there will be low grazing pressure from exotic herbivores.

Materials and methods

Study area

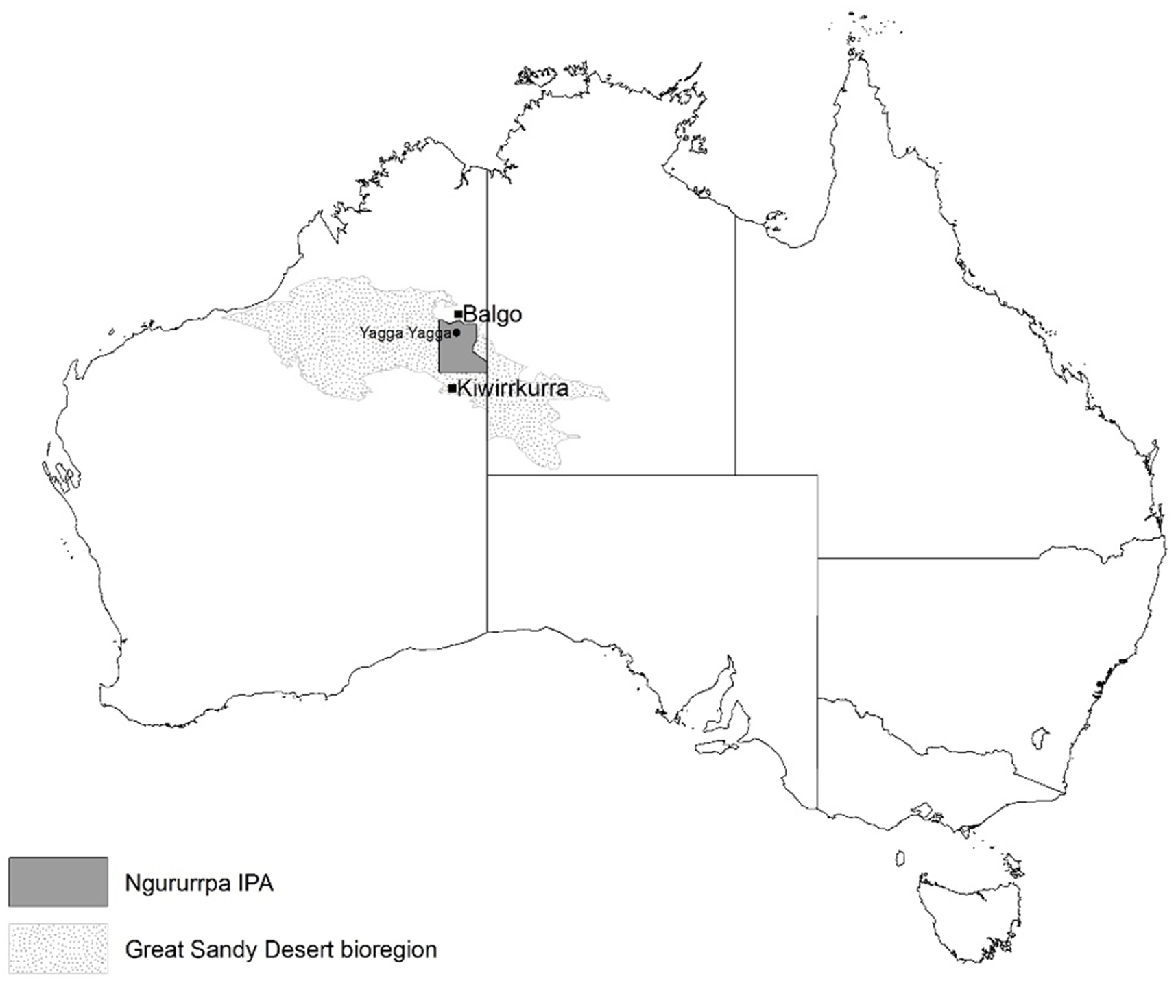

The study was conducted in the Great Sandy Desert, central eastern Western Australia, between the communities of Balgo and Kiwirrkurra (Fig. 1). Ngururrpa means ‘our country in the middle’ and is a place where many stories and people come together (Parna Ngururrpa Aboriginal Corporation 2020). Walmajarri, Kukatja, Ngarti and Wangkatjungka Traditional Owners maintained traditional nomadic lifestyles on Ngururrpa Country until the 1950s when they started moving to Balgo. They returned in 1985 when the community of Yagga Yagga was established, and other outstations followed. This resulted in a continual presence of people on Country until Yagga Yagga was closed in 2005 (Cane 2016). Planning for an IPA commenced in 2011 and culminated in the declaration of the Ngururrpa IPA in 2020 (Parna Ngururrpa Aboriginal Corporation 2020).

Map showing location of the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area within the Great Sandy Desert bioregion. Nearest inhabited Indigenous communities are shown, as well as the abandoned outstation within the IPA, Yagga yagga.

The Ngururrpa IPA comprises vast areas of sandplains and dunefields interrupted by a series of low ranges and mesas. The sandplains are vegetated with sparse Acacia shrubland over spinifex. Ephemeral lakes and claypans are scattered across the IPA, some retaining water for extended periods.

The area has a semi-arid climate with summer-dominated rainfall. Rainfall increases from south to north across the Ngururrpa IPA. For the known night parrot areas, mean annual rainfall based on ERA5 re-analysis data, from 1940 to 2023 (as recommended by Acharya et al. (2019) when actual rain gauge data is absent), varies from 310 mm in the south to 360 mm in the north, with median annual rainfall of 295–333 mm (Hersbach et al. 2023). Annual rainfall is highly variable, ranging from a minimum of 20 mm in 2019 to nearly 1000 mm in 2000.

Daily maximum temperatures at the nearest meteorological recording station at Balgo average 39°C during the hot season of wandaburru (October–December). Winters are mild, with average daily maximum and minimum temperatures in the cold season of yaltaburru (June–July) ranging between 25°C and 12°C.

Rainfall occurs mainly in the form of thunderstorms in warrgal, the wet season (late December–February), which can produce an abundance of water throughout the landscape in claypans, swamps, waterholes in creeks and rockholes. Some of these waters persist through yugari or green grass time (March–May) and the largest swamps may continue to hold water through yaltaburru. By the time the warm westerly winds arrive in ‘Goanna get up time’ or djintubalya (August–September), there are few surface waters remaining, and there may be only two long-lasting rockholes to access water by the end of wandaburru (information and Kukatja language names sourced from Ngururrpa Traditional Owners by Cane 1984).

Materials and methods

We as Rangers are working together with the scientists to learn two-ways – the science way and the traditional way.

For the traditional way, we read the country – by looking at the area and knowing where there could be water around, and looking at the plants they might eat and measuring the distance from where they could have their home to the water, to where they eat.

We are also using technology, science way, to look for nests, and protecting their area from cats, camels and bushfires. [Clifford Sunfly, Ngururrpa ranger]

We searched for night parrots during a series of surveys from 2020 to 2023. We used their distinctive calls and calling patterns (Leseberg et al. 2019, 2022) to detect the presence of night parrots by deploying acoustic recording units (ARUs, Model SM4 ‘songmeters’; Wildlife Acoustics, MA, USA) in potential roosting habitat for a minimum of 21 days per survey. The ARUs were programmed to record all night from 30 min after sunset to 30 min before sunrise.

To identify potential roosting habitat, we initially conducted a coarse vegetation assessment as we drove along a 250 km transect through the IPA, mapping all patches of lanu lanu (bull spinifex, Triodia longiceps), the species of spinifex used as a roost by night parrots in Queensland. We then identified the geological units corresponding with lanu lanu spinifex patches on the 1:250,000 Lake Mackay Geology mosaic (comprised of Stansmore Range, Lucas, Webb, Cornish, Helena and Wilson map sheets). Areas with suitable geology were then examined on high-resolution imagery (Sentinel, Landsat and Esri World Imagery) to map all areas of potential habitat on the IPA. Within each of these broad habitat areas, we zoomed into a scale of 1:2500 resolution on Esri World Imagery (date 2021) to manually map patches of old growth spinifex. At this resolution, individual mature spinifex hummocks could be seen.

Within the 20 broad areas of habitat on the IPA, we identified a total of 58 patches of mature T. longiceps habitat (>2 km apart) ranging in size from 10,000 m2 to 20 km2. During the 3-year period, 31 of these patches were visited and surveyed with an acoustic recording unit for a minimum of 21 days. Many of the patches were very remote from vehicle tracks and could be accessed only by helicopter. The subset of sites selected for survey each year was chosen by the rangers. Once in the field, the rangers chose the specific location to deploy the songmeters within the patch, usually on the basis of where the largest spinifex clumps were situated.

Some of these sites were important cultural sites where only men can go, or only women can go, that’s why we’ve got a mixed ranger team of men and women. [Clifford Sunfly]

Analysis of acoustic data was conducted using Kaleidoscope Pro Version 5 software (Wildlife Acoustics, MA, USA; see https://www.wildlifeacoustics.com/products/kaleidoscope-pro?gad_source=1) to identify all vocalisations in the frequency range of 1500–3500 Hz, within which all known night parrot calls are distributed (Leseberg et al. 2019). Search parameters were optimised using a random selection of 250 night parrot call examples manually detected from both Great Sandy Desert and East Murchison regions.

Potential night parrot calls detected during the analysis were manually verified by using a reference library comprising several thousand night parrot calls from Western Australia and Queensland. This library consists of calls recorded at sites where night parrots have been confirmed by using visual means and is therefore considered of high reliability. The library also includes multiple examples of all known call types from Western Australia and Queensland (Leseberg et al. 2019).

Night parrots are known to call predictably around their roost sites in the first hour after sunset and/or the last hour before sunrise (Murphy et al. 2017a; Leseberg et al. 2019). Accordingly, we classified sites as roosting areas where night parrots were frequently detected (i.e. on most nights of the survey) during this sunset/sunrise calling period. Night parrots also call occasionally when away from their roost sites, foraging, and will visit specific sites across multiple nights (Murphy et al. 2017a; Leseberg et al. 2019). Sites where night parrots were not detected during the sunset/sunrise calling period, but were detected calling regularly (6–50 detections) at other times of the night over multiple nights, were classified as non-roosting active areas (potentially feeding or drinking sites). Night parrots also call occasionally while transiting the landscape in flight (Leseberg et al. 2022). Sites where only occasional detections were recorded (<6 detections) outside the sunset/sunrise calling period were classified as transit areas.

Three sites classified as night parrot roosting areas were visited to document the plant species present.

The fire history of roosting areas was examined using Landsat imagery dating back 40 years to 1983, so as to assess age of spinifex and measure the impact of fires encroaching on roosting habitat. A 24-year fire history (2000–2023) was created for the project area (by Adaptive NRM), based on Landsat satellite imagery (Landsat 5, 7, 8 and 9) downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). An image library comprising an average of 6.7 images per year per scene was used to create difference images between consecutive captures to identify and map fire scars. To improve classification by reducing the spectral dimensionality of the full area under consideration, Landsat scenes were split into smaller non-overlapping regions and an unsupervised classification was performed in R (R Core Team 2021), using the R function cluster::clara (Maechler et al. 2013). This was an iterative process, with the performance of the initial classification heuristically assessed by comparison to the original, enhanced image. If improvements were needed, the analyst would repeat the process with a specific area of interest around problem scars, and/or adjust the number of clusters (usually between 6 and 35, which was set a priori by the analyst). Each region was manually inspected for fire activity and issues of commission and omission errors were identified and remapped manually before exporting the final burnt areas. To obtain additional information on frequency of fire occurrence, for the period 1983–1999, annual Landsat images were visually examined for fires occurring in close proximity to night parrot sites.

After an extensive wildfire, one roosting area was revisited to assess how much habitat remained unburnt within the patch, and whether lanu lanu spinifex was killed by the fire or able to resprout from lignotubers.

We investigated the prevalence of mammalian predators and large herbivores in the study area by using data collected during a previous track plot survey through the area, and camera-trap monitoring of roosting habitat prior to feral cat control. The track plot survey was conducted in 2016 and involved a team of rangers searching a series of 2 hectare plots for 30 person-minutes (e.g. 3 people searching for 10 min) and recording the presence of animal signs. Thirty-two 20,000 m2 plots, separated by at least 4 km, were surveyed along the 250 km length of the IPA. The camera survey involved the deployment of 10 Reconyx cameras for 176 nights within each of two 1 km2 areas of lanu lanu spinifex where night parrots had been detected. Camera images were processed manually and converted to the number of independent events per 100 trap-nights. An independent event was defined as a detection recorded at least 60 min after the previous event of the same type on the same camera.

Mammalian predator (dingo, fox, cat) scats were opportunistically collected at sites for dietary analysis. Scats were washed in nylon bags in a commercial washing machine and air dried before the contents were sorted under a dissecting microscope. Animal remains found in the scats were identified by comparing teeth, claws, scales, feathers and hair with reference material from the study area. Hairs were cross-sectioned and examined under a binocular microscope.

Results

Distribution and abundance of night parrots on the Ngururrpa IPA

At most of the sites we have found a lot of evidence of night parrot calls and nice spinifex for them to live in. [Clifford Sunfly]

Surveys of 31 sites (>2 km apart) between 2018 and 2023 showed positive detections of night parrots at 17 sites distributed across a distance of 160 km from north to south and 90 km from east to west on the Ngururrpa IPA.

Night parrots were initially detected in 2018, just inside the boundary of the Ngururrpa IPA by a neighbouring ranger group. In 2020, a collaborative survey between Agrimin mining company, Stantec Consultants and the Ngururrpa rangers successfully detected night parrots at two further sites on the IPA, 28 km apart. Later that year, Ngururrpa rangers independently recorded more calls at these sites, as well as a third site located halfway between the other two known locations. Simultaneous calls at the three sites indicated that multiple groups of birds were present, including immature birds.

In April 2021, thousands of night parrot calls were detected in two new survey areas approximately 50 and 100 km south of the previous detections. Calls were regularly recorded in the pre-sunrise and post-sunset periods, indicating that these were roosting sites.

Results of a subsequent survey in April 2022 showed that all five main sites were still occupied by night parrots. Although it is not possible to be certain of the number of birds present at a site on the basis of acoustic data only, long-term analysis of acoustic data coupled with field observations from roost sites in western Queensland suggested that estimates are possible (Nicholas Leseberg, unpubl. data). This research indicated that individual night parrots have a dominant call type. Using additional parameters available in acoustic data such as consistent differences in amplitude among calls detected during the same time period (suggesting different birds calling from different locations), and the occurrence of call and response events (suggesting a pair of birds), it is possible to build a picture of the identity and number of individuals regularly occupying a roosting area over time. Using this approach, we estimated that there were four to five birds at each of two sites separated by 50 km, and at least a pair with or without young at the other three sites. Three additional roosting areas and two non-roosting active areas (possible feeding sites) were discovered during a later survey of new sites accessed by helicopter in May 2022.

In 2023, three new roosting sites were found in an area that had not been previously surveyed. Analysis of the calling patterns at these three sites (which were all at least 5 km apart) suggested there were three to four individual birds at each site, and about 10 birds across this new area. In addition, a call was recorded at a site 35 km east of the nearest site, implying that there may be another roosting area in that direction.

Although acknowledging that population estimates using calling patterns alone are imprecise, our results suggested that up to 30 individuals have so far been detected on Ngururrpa IPA and the positive records in 17 of the 31 patches surveyed indicated a relatively high level of occupancy across mature lanu lanu habitat. Omitting sites that did not yield any calls in the hour after sunset or hour before sunrise (and thus less likely to be roosting sites) leaves 10 known roosting areas, or 33% of habitat patches surveyed. Extrapolating across the 58 patches of habitat present on Ngururrpa IPA suggests that 20 roosting areas may be currently occupied by night parrots. Assuming that at least two to four birds occur in each of these, we estimate that there could be at least 40–50 night parrots present on the Ngururrpa IPA.

Habitat

On the Ngururrpa IPA, known night parrot habitat occurs in two distinctive geological/landform settings that can occur near one another, namely, gently sloping gibber (ironstone or laterite) plains below breakaways or a laterised and deeply weathered plateau and areas of calcrete along former drainages. In both settings, all roost sites were in areas that include patches of lanu lanu spinifex more than 14 years old within the area of detection of the songmeter.

Lanu lanu spinifex was found to be associated mainly with weathered and eroded landscapes on sandstones, siltstones, and shale rock types. When these rocks are subject to deep weathering, extensive clay-loam or clayey flats can be formed, often with surface gibber (pieces of broken laterite/ferricrete duricrust formed through the weathering process). Less commonly, lanu lanu spinifex also occurs on areas of calcrete, although it appears that calcrete areas in the Ngururrpa IPA are more commonly occupied by gummy spinifex (Triodia pungens).

Trees are generally absent from the roosting habitat, but there are occasional shrubs, including acacias (A. bivenosa, A. cuthbertsonii, A. victoriae) and sennas (S. artemisioides, S. glutinosa, S. sericea).

Lanu lanu spinifex does not occur on the open sandplain and dune country, which covers the majority of the IPA and is dominated by other hummock grass species, particularly T. pungens, T. epactia, T. schinzii and T. basedowii.

Potential feeding areas occur on the alluvial soils of run-on areas and drainages originating in and adjacent to the low rocky and stony country where lanu lanu spinifex occurs. The clay-loam soils support tussock grasslands (comprising annual and perennial grasses (Eragrostis xerophila, Aristida contorta and A. latifolia, E. dielsii, Oxychloris scariosa, Dactyloctenium radulans, Iseilema membranaceum) and forbs (Rhynchosia minima, Goodenia fascicularis, Tephrosia sp. northern) with scattered shrubs (e.g. prickly acacia, A. victoriae). Some perennial grasses such as Eulalia aurea, Chrysopogan fallax, and Panicum decompositum are associated with fringes of the claypans, small watercourses and clay gilgai, which are a common feature of the habitat.

These alluvial grasslands support many species that provide important food resources for people (Cane 1984) and are potential seed resources for night parrots. Forty-two species of plants with edible seeds (including grasses, sedges and shrubs) were recorded from Ngururrpa Traditional Owners (Cane 1984). Ngururrpa people harvested seeds either directly from the plants or from ant’s nests, and processed them using wooden dishes and grinding stones to make seedcakes that would be cooked on the fire (Cane 1984). Grasses that produce an abundance of palatable seeds include burrandjarrig (button rass, D. radulans), miarr miarr (brown beetle grass, Diplachne fusca subsp. muelleri), willinggiri (Australian millet, Panicum decompositum) and rice grass (Xerochloa laniflora). Other potential night parrot food plants in this habitat are four species of Sclerolaena (S. bicornis, S. cornishiana, S. crenata, S. cuneata), two species of Trianthema (T. triquetra, T. glossostigma) and two species of Portulaca, bulyulari and wayali (P. fillifolia and P. oleracea).

Beyond the alluvial soils, other important seed resources for people that could be shared with night parrots include two grasses that rapidly emerge and seed after fire in sandplain habitat, namely, lugarra (Fimbristylis oxystachya) and yidagadji (Yakirra australiense). The samphire, mungil (Tecticornia verrucosa), grows on the occasional claypan. Seeds of all three plants were significant in the diets of Ngururrpa people (Cane 1984).

Impact of fire on night parrot habitat

We worry that when a fire starts it will keep going and destroy the night parrot’s home. [Clifford Sunfly]

Analysis of fire history showed that extensive large fires occurred on the Ngururrpa IPA in the mid-1970s, 2000–2002, 2011, 2017 and 2023. In all of these periods, fires encroached on areas of lanu lanu spinifex habitat. Considerable fire activity was also recorded in 2004, 2006, 2007, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2018, or whenever the previous 24-month rainfall exceeded 700 mm.

Fire frequency was highest in tussock grasslands on alluvial soils (more than four fires since 2000) and lowest on the gibber-covered slopes that support night parrot roosting habitat (unburnt or only one fire in the fire history period 2000–2023). Open spinifex sandplains and dune areas supporting other species of spinifex have an intermediate fire frequency (usually two or three fires occurring since 2000, with some areas in the north burning four or five times).

In the spinifex sandplain country, cumulative rainfall between fires was usually ~2000 mm minimum rainfall, enabling areas to regrow enough to reburn every 6–10 years.

In the lanu lanu spinifex habitat, fires mostly occurred when at least 2500 mm of rain had fallen since the previous fire (rainfall since fire, RSF), but more commonly fires occurred in areas that had received >3500 mm since the last fire. All locations where night parrots roosting sites were recorded contained habitat that was at least 4000 mm RSF (minimum age approximately 14 years), which we define as mature lanu lanu spinifex.

We examined the impact of fire on the extent of mature roosting habitat available in the largest known area of occupied night parrot habitat on the Ngururrpa IPA after the four most recent major fire events. Night parrots have been continuously present in this 52 km2 core area of lanu lanu spinifex since they were first detected in 2021 and multiple roosting sites have been found within the patch.

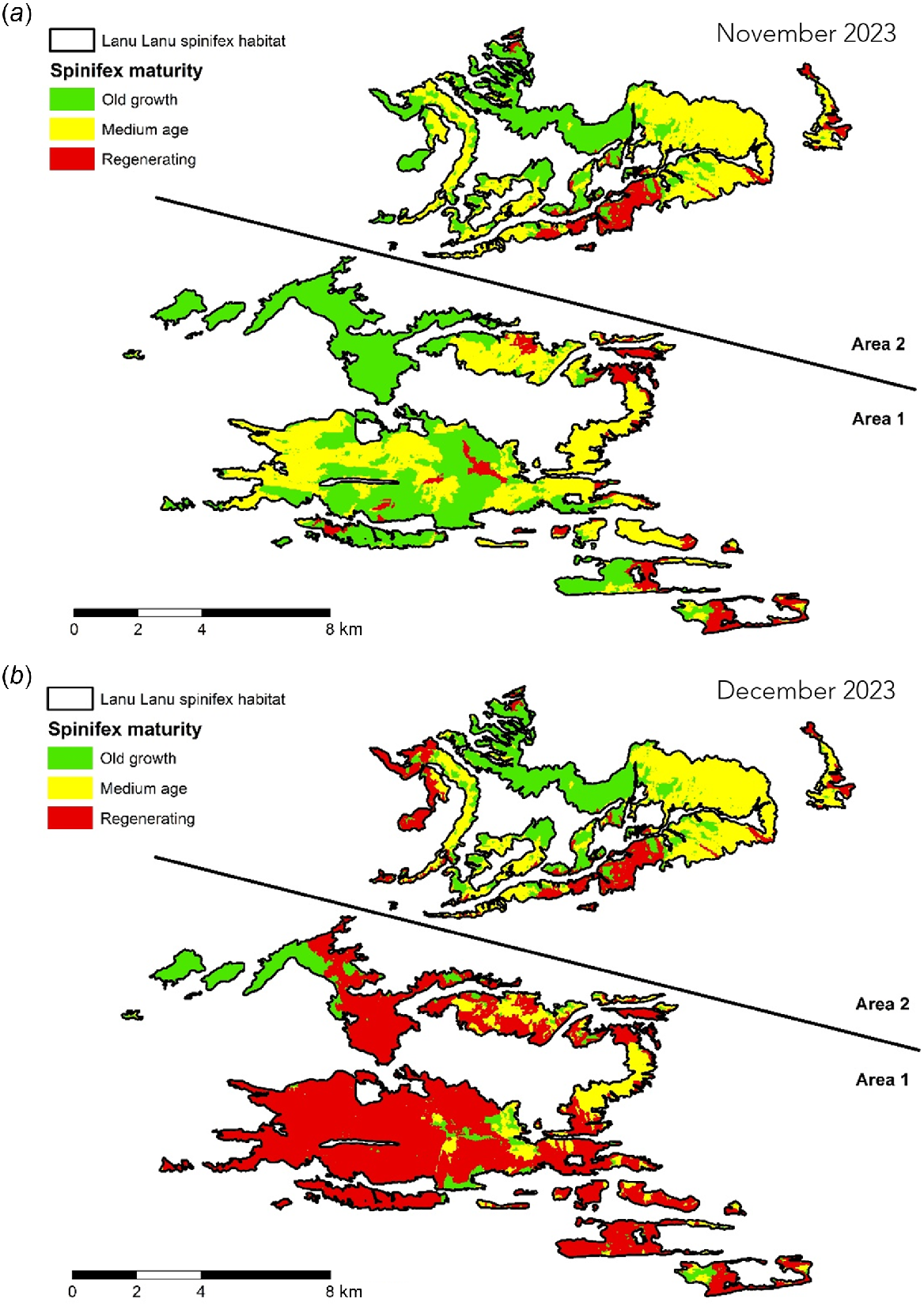

We found that fires affected significant areas of this core lanu lanu habitat in 2003, 2011 and 2017 (Table 1), but the most recent fire in 2023 resulted in the largest reduction of old growth habitat in this stand of spinifex in the 40 years that satellite imagery is available. Despite the presence of a series of claypans, creeklines, small linear 2019 firescars and a road dissecting the area, over 2 days in December 2023, a lightning-ignited wildfire reduced the areal extent of old growth habitat by 76%, from 27.96 km2 to 6.60 km2, leaving only scattered fragments of unburnt roosting habitat, with most patches smaller than 50,000 m2 (Fig. 2).

| Spinifex age | Area 1 (52 km2) | Area 2 (31 km2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2011 | 2017 | 2023 | 2003 | 2011 | 2017 | 2023 | ||

| Old growth | 22.4 | 22.6 | 38.7 | 12.2 | 66.6 | 36.2 | 39.5 | 35.5 | |

| Medium age | 0.0 | 42.8 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 13.9 | 0.1 | 47.5 | |

| Regenerating | 77.6 | 34.6 | 47.4 | 75.3 | 33.4 | 49.9 | 60.4 | 17.0 | |

Old growth spinifex, >4000 mm rainfall since the last fire; medium age, 2000–4000 mm rainfall since fire; and regenerating, <2000 mm rainfall since the last fire.

Impact of a hot summer wildfire on the extent of old-growth spinifex in two adjacent areas of night parrot roosting habitat. Multiple night parrot roosting sites had been recorded in Area 1 before the fire. Old-growth spinifex (>15 years old) suitable for roosting is shown in green (a) before the fire and (b) after the fire in December 2023.

Ground surveys conducted 2 months after the fire showed that there was no sign of the lanu lanu spinifex resprouting, whereas both the dominant tussock grass in the adjacent alluvial habitat (Eragrostis xerophila) and the other species of spinifex (Triodia pungens) in the neighbouring sandplains had rapidly resprouted after the fire.

Fortunately, an adjacent patch of lanu lanu habitat was less affected by the 2023 fire. This patch of spinifex comprised more medium-aged spinifex, but provided an additional 10 km2 of mature spinifex habitat within 10 km of the burnt roosting sites. Night parrots were not detected in this patch during the 2021 surveys; however, at least two birds were heard calling just after sunset in the previously surveyed area in February 2024.

Predators in night parrot habitat

Dingoes are the main predator out here. We see a lot on the cameras. We think the cats don’t want to travel much through here because of all the dingoes. We don’t think the dingoes would be a predator for the night parrots. Cats are more stealthier, dodging all the dingoes. [Clifford Sunfly]

Overall, cats and dingoes are common throughout the Ngururrpa IPA. Foxes are also present, but have a lower frequency of occurrence. The 2016 track-plot surveys of 32 2 hectare plots distributed along a 250 km transect through the IPA recorded cats in 53% of plots, dingoes in 32% of plots and foxes in 22% of plots.

However, within the night parrot roosting habitat, dingoes are the most frequently recorded predatory species. They were recorded on cameras at a rate of 5.7 detections per 100 trap-nights, more than 10 times the frequency that cats were recorded (Table 2). Pairs of dingoes were often captured on camera and a family of dingoes with three pups was photographed within 500 m of a songmeter that recorded frequent night parrot calls.

| Species | Detection rate (events/100 nights) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Queensland NP site | Ngururrpa | ||

| Cats | 0.42 | 0.51 | |

| Dogs/dingos | 0.84 | 5.73 | |

| Foxes | 0 | 0.10 | |

| Macropods | 4.60 | 0.03 | |

| Cattle | 0.73 | 0 | |

| One-humped camels | 0.05 | 7.75 | |

| Horses | 0.05 | 0 | |

| Night parrot | 0 | 0.03 | |

In contrast, cat and fox incursions into the night parrot habitat were rare. Only three fox detections were recorded, all at the southern study site. There were two detections 2 days apart in June, and a third 5 months later.

Another quiet one is the fox. We only saw one fox on the camera, dingoes are probably keeping them away too. [Clifford Sunfly]

Cats were also rarely recorded. There was only a single detection on each of 5 of the 10 cameras in 6 months at the northern study site, and 11 detections across 6 of the 10 cameras at the southern study site in 6 months of survey.

Predator diets

Goannas (Varanus spp.) and blue-tongued lizards (Tiliqua multifasciata) were the most consistently recorded prey for dingoes on the Ngururrpa IPA. More than half of the 59 dingo scats examined contained remains of goannas (Table 3). These were primarily ridge-tailed monitor (Varanus acanthurus), but some sand goannas (V. gouldii) were also detected. Other reptilian prey included thorny devil (Moloch horridus) and other smaller dragons and skinks.

| Prey type | August 2016 | November 2021 | February 2024 | Frequency of occurrence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 scats | 23 scats | 28 scats | |||

| Feral cat | 2 | 0 | 7 | 15 | |

| Rodent | 0 | 3 | 8 | 19 | |

| Macropod | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Camel | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Marsupial mole | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Bird | 1 | 2 | 8 | 19 | |

| Goanna | 4 | 15 | 15 | 58 | |

| Blue-tongue | 1 | 4 | 12 | 29 | |

| Other lizard | 3 | 5 | 2 | 17 |

Feral cat contributed the greatest biomass to dingo diet. Overall, cat remains were found in nine predator scats. Frequency of occurrence of cat in dingo diet peaked in the final survey in February 2024 when 25% of dingo scats contained cat remains (Table 3). On the basis of claw size, these included five adult cats and two kittens. Cat was represented in dingo diets at all three night parrot sites visited in February 2024 (across an area spanning 50 km). Furthermore, a photograph of a dingo carrying a cat in its mouth was captured on a camera at another night parrot site more than 50 km farther north in November 2023.

Both small rodents and birds (not including night parrot) were recorded in 19% of dingo scats. Other mammals including red kangaroo (Osphranter rufus), marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus) and one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius) were occasionally eaten.

Of the five fox scats collected from Ngururrpa in 2016, four contained rodent, one contained small dasyurid, one contained bird feathers (fairywren, Malurus spp.), three contained small reptile and one contained beetles.

Seven cat scats were analysed from 2016; five had small rodent, four had small bird, five had small reptile and three had invertebrates.

Feral herbivores

Our cameras have shown us what’s going on at our night parrot sites. Camels are everywhere in the night parrot habitat. We see them disturbing the spinifex. There’s that hidden highway for them. If you learn how to read the country you can see that hidden highway for them following around the claypans. [Clifford Sunfly]

The Ngururrpa IPA has never been used to graze stock. However, feral camels were frequently recorded in the night parrot roosting habitat, occurring at a rate of 7.8 detections per 100 camera-trap nights, usually in groups of at least six animals.

After the December 2023 fire, camels congregated in large numbers (approximately 100) in the regenerating grassy areas within the roosting habitat. We observed them grazing on the broad-leafed neverfail (Eragrostis setifolia) and saw regular evidence of browsing on the chenopodiaceous shrubs, including five species of Sclerolaena and one species of bluebush (Maireana georgei), with virtually every plant we observed being browsed almost to the base.

Discussion

We didn’t know about night parrots before but now we know about it we want to protect it. [Samuel Galova, Ngururrpa rangers]

Before we detected night parrot calls on the Ngururrpa IPA in 2020, there was little awareness that this cryptic, nocturnal bird was still persisting on Ngururrpa Country. Once the song of the bird was played, people recalled hearing its whistle as children, and being told that it was an evil spirit. Although we are yet to uncover further information about the cultural significance of night parrots on Ngururrpa Country, the Ngururrpa rangers have successfully combined their Traditional Knowledge of Country with science and technology to conduct extensive surveys for the species across the IPA, with an unprecedented level of success. Using their detailed knowledge of the distribution of habitats suitable for roosting and feeding and water resources, their capacity to navigate access to appropriate sites, their ability to read the country and pinpoint suitable survey points, and their willingness to share and learn from other night parrot experts, more night parrot sites have been detected on the Ngururrpa IPA than anywhere else in the world.

Although more than 1200 km apart, and separated by the Northern Territory, there are certain similarities between the habitats occupied by night parrots in south-western Queensland and the Ngururrpa IPA.

In both areas, night parrots were found to roost in long-unburnt stands of the same species of spinifex (lanu lanu or Triodia longiceps) growing on similar geological types comprising ironstone (laterite gibber) plains adjacent to breakaways or sandstone rises.

In both areas, the lanu lanu spinifex habitats are situated in close proximity to more productive grasslands occurring on the alluvial soils of run-on areas and drainages originating in low rocky country, which provide potential feeding areas. The seasonal availability of seed resources is well known to Ngururrpa Traditional Owners. As documented in Cane (1984), the samphire, mungil (Tecticornia verrucosa), is one of the only seeds that can be obtained in the hottest season, but after summer rains, there is a succession of seed resources, beginning with spinifex species, followed by the early succulents (Portulaca spp.) and then a great diversity of grass seeds from the end of yugari or green grass time (May–June) until the end of winter.

A major difference between the Queensland and Ngururrpa study areas is the flammability of the vegetation in the broader landscape surrounding the night parrot habitat. In Queensland, the relatively small pockets of lanu lanu spinifex are surrounded by either bare stony ground, sparse non-spinifex tussock grasslands or chenopodiaceous vegetation where plant biomass is kept low through grazing by stock and native herbivores. These areas of bare ground or very sparse vegetation limit the passage of any fires that do start (Murphy et al. 2018). In contrast, the lanu lanu habitat of the Great Sandy Desert is embedded within a landscape of highly flammable spinifex sandplains and dunefields that continue to accumulate fuel until they are inevitably burnt in large, hot wildfires every 6–10 years. These fires regularly encroach on night parrot feeding and roosting habitats, meaning that fire is a much more significant disturbance to night parrot habitat in Western Australia than it is in Queensland, where researchers found no evidence of fire within the two properties occupied by night parrots, on the basis of Landsat and aerial photographs, over a 60-year period (Murphy et al. 2018). Field-based observations of some small fires were made in the same area between 2013 and 2016; however, these were small in extent (less than 10,000 m2) and extinguished because of lack of contiguous fuel (S. Murphy, pers. comm.)

The observation that lanu lanu spinifex was unable to resprout after a hot summer wildfire suggests that regeneration of hummocks will be slow, relying on germination from seed. We are yet to confirm minimum size of hummocks that can be used for roosts, but early indications from fire ages at sites where night parrots have been detected at Ngururrpa suggest that at least 4000 mm of rainfall would be required to generate suitable habitat, which would take, on average, 14 years (much longer than the average fire-return time for the surrounding sandy spinifex habitats), but the largest hummocks were approximately 20 years post-fire. Although fires never entirely remove all available mature spinifex habitat in an area, when the extent of roosting habitat is reduced to tiny fragments, there is the potential for intense predation pressure on the small unburnt patches within a large firescar. Studies elsewhere have suggested that an increase in activity of cats (Moore et al. 2024) and/or foxes (Geyle et al. 2024) after fire led to a decline in bilby populations. Surveys are currently underway to determine the level of predation pressure on remnant patches of vegetation within the 2023 firescar and whether night parrots have persisted in this area.

There is no current knowledge on how far night parrots can disperse if their roosting habitat is destroyed by fire, and how easily they can create new tunnels into spinifex hummocks. The limited information on daily distances travelled from two tagged birds suggests that birds can fly up to 40 km in a night (Murphy et al. 2017b), and thus long-distance dispersals are possible. Birds may be vulnerable to predation during their long-distance flights and while constructing new tunnels.

Fires during nesting periods would be particularly devastating. If active nests were burnt, chicks would die. Even if the nesting hummocks remained unburnt within mostly burnt habitat, the distance the parents might have to travel to obtain food may be too great to provision the chicks in the nest.

Although large hot wildfires are likely to be a major threat to night parrots at Ngururrpa, there have been only relatively short periods of time where traditional fire management was not conducted, with the main absences of people being between 1955 and 1985 and between 2006 and 2011 (Cane 2016). While people were present, burning would have regularly occurred as part of food-harvesting activities. People used fire to promote food plants, and assist with hunting (Cane 1984). For example, people burn small patches of spinifex to promote the growth of guru (bush tomatoes, Solanum chippendalei), expose burrows where goannas are hibernating and to increase the chance of finding kipara (bush turkeys, Ardeotis australis), which are attracted to both smoke and recently burnt ground (Clifford Sunfly, pers. obs.).

Even in the period between the closure of Yagga Yagga and the commencement of broadscale fire management by Ngururrpa rangers in 2021, neighbouring community members conducted some burning along the main road that traverses the IPA. The combination of a relatively consistent presence of people, and the diversity of habitats on the IPA has resulted in a more benign regional fire regime than in adjacent areas of country with endless sandplains, where there is nothing to stop large wildfires.

Since regular ranger work commenced in 2020, younger rangers have been trained in both contemporary and traditional burning techniques. Cool-season burning is a priority action in the IPA annual workplan (Parna Ngururrpa Aboriginal Corporation 2020). In most years, rangers collaborate with neighbours and partners in landscape-scale aerial incendiary burning programs (coordinated by the Indigenous Desert Alliance) that aim to break up single-aged fuel loads to reduce the spread of hot summer wildfires ignited by lightning.

Before we knew about night parrots we used to burn everywhere, every hunting trip we would light fires, but now we are being more careful about where we are burning. We still need to do a lot of burning though. [Ryan Sunfly, Ngururrpa rangers]

As our information on the distribution of night parrots and their habitats on the Ngururrpa IPA continues to improve, burning programs can become more targeted in their protection of key night parrot roosting areas.

We’ve done all our training to know how to protect against these things. And we want to do more training. We need to do more work to find night parrots and make a fire break around all these areas. [Clifford Sunfly]

Although most anthropogenic fires are deliberately lit for hunting and land-management reasons, fire is also a vital means of communication for people travelling between local communities, when they need to alert families to the location of broken-down vehicles and the rangers worry that this could negatively affect night parrot roosting habitat.

We want to put up some signs telling people not to burn in certain areas, but not too close to the sites. We want to put out a warning to tourists and our local neighbours if they do have to make a smoke signal not to burn the night parrot spinifex. [Clifford Sunfly]

Dingoes are the dominant predator at both the Ngururrpa and Queensland night parrot sites. At the Queensland site, dingoes were recorded twice as frequently as cats, and foxes were absent. On Ngururrpa Country, dingoes were recorded 10 times more frequently than cats and foxes occurred at low densities.

The extent of dingo predation on cats is a significant feature of the Ngururrpa ecosystem. Although there was some evidence of dingo predation on cats at the Queensland night parrot site, macropods were the staple prey for dingoes in this environment (Murphy et al. 2018). In the extensive spinifex grasslands of the Great Sandy Desert where macropods are scarce, feral cat is the most abundant medium-sized mammal, and is a favoured food resource for dingoes, which are otherwise subsisting on reptiles, predominantly goannas and blue-tongues.

Regular consumption of cats by dingoes could be an important factor in the survival of threatened species on the Ngururrpa IPA. Cats are regarded as a significant threat to night parrots on the basis of historical accounts of cats bringing in remains of night parrots to the Alice Springs Telegraph Station (Ashby 1924), frequent movement of cats through habitats shared with night parrots in Queensland Murphy et al. 2022) and observations of cats visiting night parrot nesting areas (in Queensland) when nestlings become vocal just prior to fledging (N. Leseberg, unpubl. data). Controlling feral cats is considered the single most effective management strategy for the night parrot (Leseberg et al. 2023). Cats are also a known threat to other rare and declining species [greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis) and great desert skink (Liopholis kintorei)] that occur in close proximity to the night parrot sites (DCCEEW 2023; Indigenous Desert Alliance 2022), but if dingoes are applying constant predation pressure on the cat population, this threat may be ameliorated.

The presence of foxes at Ngururrpa is in contrast to the Queensland night parrot sites, where there has been no sign of foxes since night parrots were detected (Murphy et al. 2018). Foxes are a potential threat to nesting night parrots. In an experiment where artificial night parrot nests were created in spinifex hummocks in the Simpson Desert, foxes were the main predator to remove eggs from nests within spinifex (Spencer et al. 2021). Although fox is not commonly recorded in dingo diet, dingoes are known to kill foxes and not eat them (Moseby et al. 2012) and it is likely that foxes avoid areas with a heavy dingo presence. Thus, even though we cannot prove that dingoes play a key role in the ecosystem night parrots inhabit at Ngururrpa, we suggest that any actions that might disrupt dingo populations could be risky and should be avoided. For this reason, only target-specific predator control techniques are being considered for Ngururrpa (e.g. Felixer grooming traps for cats).

We as rangers are using traditional and modern ways of keeping the cat population down. We are using Felixers because they only kill cats and foxes. We are bringing together the knowledge we got from our cameras about the cats walking around the clay pans with our Traditional Knowledge and skills to read the country to choose a good spot to put the Felixers. [Clifford Sunfly]

An absence of grazing stock across the landscape is likely to be an important factor in the persistence of night parrots across so many patches of suitable habitat on the Ngururrpa IPA. Although night parrots do co-exist with cattle in south-western Queensland, it seems that grazing pressure at the sites where night parrots occur has been historically low (Murphy et al. 2018). Recent research in Queensland has shown that the removal of grazing has increased the availability of known night parrot food plants (N. Leseberg, unpubl. data), whereas other studies have found correlations between grazing pressure and declines of granivorous species (Franklin et al. 2005). Most of the surrounding habitat matrix on the Ngururrpa IPA is dominated by relatively unpalatable spinifex species; if grazing stock were introduced to the area, they would certainly focus on the small patches of more palatable productive vegetation that are likely to be key to the survival of night parrots.

Although camels are predominantly browsers, they may compete with night parrots for chenopodiaceous food resources. Night parrots in Queensland are known to consume species of Sclerolaena, but it is not known if the birds consume the seeds or fleshy leaves of the plant (S. Murphy, N. Leseberg, unpubl. data). High densities of camels may also cause significant disturbance to roosting night parrots, on the basis of historical references to night parrots being regularly flushed from the spinifex by horses and cattle (Whitlock 1924). Camels may also compete with night parrots for precious water resources in dry periods when free water is available only in a couple of permanent rockholes known on the IPA. Physiological modelling suggests that night parrots would need regular access to water in the hot summer months (Kearney et al. 2016). The rangers are also concerned about large herds of camels depleting other surface-water sources that could otherwise maintain dingo packs for longer.

Camels could be draining the water from the claypans. If there’s too many camels there might be less water for the dingoes. If there’s less dingoes there might be more cats and more predation on night parrots. [Clifford Sunfly]

Conclusions and recommendations

We would like to spend more time on Country to find where they are and understand what they are doing, and listen to their calls to try to work out what they are saying to each other.

We want those scientists to come and help us catch some night parrots and tag them. We want their expert advice. We also need more snake cams (inspection cameras) too and more songmeters. And a kit for collecting scats for DNA.

One day we would love to have our own research facility for doing our night parrot surveys. It could be a research station for all the endangered species. Maybe we could partner with a mining company or a conservation organisation. It would be our dream to have our own research base on Ngururrpa. [Clifford Sunfly]

We recommend establishing a long-term monitoring program for night parrots on Ngururrpa Country to investigate survivorship and recruitment of birds, and determine whether the population is stable, increasing or declining. This could be undertaken with a combination of long-term acoustic recording at key monitoring sites, and potentially eDNA analysis of scat or feather samples collected from roosting sites to determine the number of individuals present in areas. Knowledge of daily distances travelled, and seasonal movement patterns would also help us interpret results of our acoustic monitoring. DNA analysis of scats to study the diet of night parrots in this area would help us ensure we are protecting their feeding grounds.

To ensure this critically important population of night parrots continues to thrive, we recommend maintaining the remoteness and wildness of this intact landscape, with minimal disturbance from people and vehicles and continued exclusion of grazing stock and weeds such as buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris). Our results suggest that management should focus on strategic burning to reduce fuel loads in the landscape surrounding known and potential night parrot roost habitat, and that any predator-control methods are limited to those that do not harm dingoes. If future monitoring shows significant impacts of feral camels, culling may be required.

Finally, ‘If there’s any mining proposed we want to check out the area first, for sacred sites, night parrots, bilby sites and tjalapa sites. We need a chopper to get to the sites far from the road. We have to check properly before any mining – before, during and after.’ [Samuel Galova, Ngururrpa rangers].

Declaration of funding

This project was funded by the State NRM Community Stewardship grants and the Resilient Landscapes Hub of the National Environmental Science Program.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the Ngururrpa rangers and Traditional Owners who assisted with night parrot surveys and supported this work, particularly Samuel Galova, Gary Njamme, Kathryn Njamme, Bruce Njamme, Ryan Sunfly and Melissa Sunfly. We acknowledge the great work of Jamie Brown and the Paruku rangers and WWF scientists who first found night parrots next-door and inspired us to look for them on Ngururrpa. We thank Kate Crossing for managing the ranger programs and obtaining funding for the work. We appreciate advice from Steve Murphy and Simon Nally and are grateful for opportunities to share knowledge with the regional night parrot working group led by Malcolm Lindsay. We appreciate the detailed fire-mapping work conducted by Steve and Rachel Murphy from Adaptive NRM. Last, we acknowledge the work of the Stantec consultants and Agrimin staff who we worked with on some of the initial surveys that confirmed the presence of night parrots on Ngururrpa Country and thank the Thylation Foundation for providing the Felixers.

References

Acharya SC, Nathan R, Wang QJ, Su C-H, Eizenberg N (2019) An evaluation of daily precipitation from a regional atmospheric reanalysis over Australia. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 23, 3387-3403.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ashby E (1924) Notes on extinct or rare Australian birds, with suggestions as to some of the causes of their disappearance. Emu – Austral Ornithology 23, 178-183.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release [Accessed 14 April 2024]

Bliege Bird R, Bird DW, Fernandez LE, Taylor N, Taylor W, Nimmo D (2018) Aboriginal burning promotes fine-scale pyrodiversity and native predators in Australia’s Western Desert. Biological Conservation 219, 110-118.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ensbey M, Legge S, Jolly CJ, Garnett ST, Gallagher RV, Lintermans M, Nimmo DG, Rumpff L, Scheele BC, Whiterod NS, Woinarski JCZ, Ahyong ST, Blackmore CJ, Bower DS, Burbidge AH, Burns PA, Butler G, Catullo R, Chapple DG, Dickman CR, Doyle KE, Ferris J, Fisher DO, Geyle HM, Gillespie GR, Greenlees MJ, Hohnen R, Hoskin CJ, Kennard M, King AJ, Kuchinke D, Law B, Lawler I, Lawler S, Loyn R, Lunney D, Lyon J, MacHunter J, Mahony M, Mahony S, McCormack R, Melville J, Menkhorst P, Michael D, Mitchell N, Mulder E, Newell D, Pearce L, Raadik TA, Rowley JJL, Sitters H, Southwell DG, Spencer R, West M, Zukowski S (2023) Animal population decline and recovery after severe fire: relating ecological and life history traits with expert estimates of population impacts from the Australian 2019–20 megafires. Biological Conservation 283, 110021.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Franklin DC, Whitehead PJ, Pardon G, Matthews J, McMahon P, McIntyre D (2005) Geographic patterns and correlates of the decline of granivorous birds in northern Australia. Wildlife Research 32(5), 399-408.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Molnár Z, Robinson CJ, Watson JEM, Zander KK, Austin B, Brondizio ES, Collier NF, Duncan T, Ellis E, Geyle H, Jackson MV, Jonas H, Malmer P, McGowan B, Sivongxay A, Leiper I (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability 1(7), 369-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Garnett ST, Woinarski JCZ, Barry Baker G, Berryman AJ, Crates R, Legge SM, Lilleyman A, Luck L, Tulloch AIT, Verdon SJ, Ward M, Watson JEM, Zander KK, Geyle HM (2024) Monitoring threats to Australian threatened birds: climate change was the biggest threat in 2020 with minimal progress on its management. Emu – Austral Ornithology 124(1), 37-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Geyle HM, Schlesinger C, Banks S, Dixon K, Murphy BP, Paltridge R, Doolan L, Herbert M, North Tanami Rangers, Dickman CR (2024) Unravelling predator–prey interactions in response to planned fire: a case study from the Tanami Desert. Wildlife Research 51, WR24059.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hersbach H, Bell B, Berrisford P, Biavati G, Horányi A, Muñoz Sabater J, Nicolas J, Peubey C, Radu R, Rozum I, Schepers D, Simmons A, Soci C, Dee D, Thépaut J-N (2023) ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). Available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7 [Accessed 21 March 2024]

Indigenous Desert Alliance (2022) ‘Looking after Tjakura, Tjalapa, Mulyamiji, Warrarna. A National Recovery Plan for the Great Desert Skink (Liopholis kintorei).’ Available at http://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/biodiversity/threatened/recovery-plans

Kearney MR, Porter WP, Murphy SA (2016) An estimate of the water budget for the endangered night parrot of Australia under recent and future climates. Climate Change Responses 3, 14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leiper I, Zander KK, Robinson CJ, Carwadine J, Moggridge BJ, Garnett ST (2018) Quantifying current and potential contributions of Australian indigenous peoples to threatened species management. Conservation Biology 32, 1038-1047.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Leseberg NP, Murphy SA, Jackett NA, Greatwich BR, Brown J, Hamilton N, Joseph L, Watson JEM (2019) Descriptions of known vocalisations of the Night Parrot Pezoporus occidentalis. Australian Field Ornithology 36, 79-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leseberg NP, McAllan IAW, Murphy SA, Burbidge AH, Joseph L, Parker SA, Jackett NA, Fuller RA, Watson JEM (2021a) Using anecdotal reports to clarify the distribution and status of a near mythical species: Australia’s Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). Emu – Austral Ornithology 121(3), 239-249.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leseberg NP, Venables WN, Murphy SA, Jackett NA, Watson JEM (2022) Accounting for both automated recording unit detection space and signal recognition performance in acoustic surveys: a protocol applied to the cryptic and critically endangered Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). Austral Ecology 47(2), 440-455.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leseberg NP, Kutt A, Evans MC, Nou T, Spillias S, Stone Z, Walsh JC, Murphy SA, Bamford M, Burbidge AH, et al. (2023) Establishing effective conservation management strategies for a poorly known endangered species: a case study using Australia’s Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). Biodiversity and Conservation 32, 2869-2891.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindsay M, Paltridge RM, Leseberg NP, Jacket NA, Murphy SA, Karajarri Rangers, Ngurrara Rangers, Nyangumarta Rangers, Kija Rangers, Gooniyandi Rangers, Paruku Rangers, Ngurra Kayanta Rangers, Ngururrpa Rangers, Kiwirrkurra Rangers, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa Martu Rangers, Birriliburu Rangers, Wiluna Martu Rangers, Nharnuwangga Wajarri Ngarlawangga Warida Rangers (2024) How aboriginal rangers came to co-lead night parrot conservation: ranger survey effort in Western Australia 2017-2023. Wildlife Research 51, WR24094.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moore H, Yawuru Country Managers, Bardi Jawi Oorany Rangers, Nyul Nyul Rangers, Nykina Mangala Rangers, Gibson LA, Dziminski MA, Radford IJ, Corey B, Bettink K, Carpenter FM, McPhail R, Sonneman T, Greatwich B (2024) Where there’s smoke, there’s cats: long-unburnt habitat is crucial to mitigating the impacts of cats on the Ngarlgumirdi, greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis). Wildlife Research 51, WR23117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moseby KE, Neilly H, Read JL, Crisp HA (2012) Interactions between a top order predator and exotic mesopredators in the Australian rangelands. International Journal of Ecology 2012, 250352.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy SA, Austin JJ, Murphy RK, Silcock J, Joseph L, Garnett ST, Leseberg NP, Watson JEM, Burbidge AH (2017a) Observations on breeding Night Parrots (Pezoporus occidentalis) in western Queensland. Emu – Austral Ornithology 117(2), 107-113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy SA, Silcock J, Murphy R, Reid J, Austin JJ (2017b) Movements and habitat use of the night parrot Pezoporus occidentalis in south-western Queensland. Austral Ecology 42(7), 858-868.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy SA, Paltridge R, Silcock J, Murphy R, Kutt AS, Read J (2018) Understanding and managing the threats to Night Parrots in south-western Queensland. Emu – Austral Ornithology 118(1), 135-145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy SA, McGregor H, Leseberg NP, Watson J, Kutt AS (2022) Feral cat GPS tracking and simulation models to improve the conservation management of night parrots. Wildlife Research 50, 325-334.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

National Indigenous Australians Agency (2023) Indigenous protected areas. Available at https://www.niaa.gov.au/our-work/environment-and-land/indigenous-protected-areas-ipa [Accessed 14 April 2024]

O’Bryan CJ, Garnett ST, Fa JE, Leiper I, Rehbein JA, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Jackson MV, Jonas HD, Brondizio ES, Burgess ND, Robinson CJ, Zander KK, Molnár Z, Venter O, Watson JEM (2021) The importance of Indigenous Peoples’ lands for the conservation of terrestrial mammals. Conservation Biology 35, 1002-1008.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pyke GH, Ehrlich PR (2014) Conservation and the holy grail: the story of the night parrot. Pacific Conservation Biology 20(2), 221-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Renwick AR, Robinson CJ, Garnett ST, Leiper I, Possingham HP, Carwardine J (2017) Mapping Indigenous land management for threatened species conservation: an Australian case-study. PLoS ONE 12(3), e0173876.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ruscalleda-Alvarez J, Cliff H, Catt G, Holmes J, Burrows N, Paltridge R, Russell-Smith J, Schubert A, See P, Legge S (2023) Right-way fire in Australia’s spinifex deserts: an approach for measuring management success when fire activity varies substantially through space and time. Journal of Environmental Management 331, 117234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Spencer EE, Dickman CR, Greenville A, Crowther MS, Kutt A, Newsome TM (2021) Carcasses attract invasive species and increase artificial nest predation in a desert environment. Global Ecology and Conservation 27, e01588.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Szabo JK, Khwaja N, Garnett ST, Butchart SHM (2012) Global patterns and drivers of avian extinctions at the species and subspecies level. PLoS ONE 7, e47080.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whitlock FL (1924) Journey to Central Australia in search of the night parrot. Emu – Austral Ornithology 23(4), 248-281.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woinarski JCZ, Murphy BP, Legge SM, Garnett ST, Lawes MJ, Comer S, Dickman CR, Doherty TS, Edwards G, Nankivell A, Paton D, Palmer R, Woolley LA (2017) How many birds are killed by cats in Australia? Biological Conservation 214, 76-87.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woinarski JC, Stobo-Wilson AM, Crawford HM, Dawson SJ, Dickman CR, Doherty TS, Fleming PA, Garnett ST, Gentle MN, Legge SM, et al. (2022) Compounding and complementary carnivores: Australian bird species eaten by the introduced European red fox Vulpes vulpes and domestic cat Felis catus. Bird Conservation International 32(3), 506-522.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |