Traditional owner-led wartaji (dingo) research in Pirra Country (Great Sandy Desert): a case study from the Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area

Bradley P. Smith A * , Jacob Loughridge B ,

A * , Jacob Loughridge B , A

B

C

D

Abstract

This article may contain images, names of or references to deceased Aboriginal people.

The Nyangumarta people are the Traditional Owners of more than 33,000 km2 of land and sea in north-western Australia, encompassing Pirra Country (The Great Sandy Desert) and nearby coastal areas. They are also the custodians and managers of the Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area (IPA). The wartaji (or dingo) holds immense cultural significance for the Nyangumarta people and is a vital part of a healthy Country. This inspired the community and rangers to focus on the wartaji as a key part of the management objectives of the IPA. We detail the development of the resulting collaborative research project between the IPA rangers and university-based scientists. The project not only presented an opportunity for the Nyangumarta community to deepen their understanding of wartaji residing on their Country, but also upskilled the Nyangumarta rangers in wartaji monitoring and management. This project is a testament to the importance of First Nations groups developing and addressing their research priorities. IPA-managed lands and associated ranger programs offer the perfect opportunity, funding and support to make these conservation-related decisions and implement actions. The collaboration with academic and non-academic researchers promises to enhance this conservation effort through mutual learning.

Keywords: conservation management, dingo, Great Sandy Desert, Indigenous Protected Areas, Indigenous rangers, Nyangumarta Warrarn, Pirra Country, wartaji.

Introduction

Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) are areas of land and sea managed by First Nations groups to protect and conserve biodiversity and cultural values, in line with Traditional Owner objectives (see Smyth 2006; Ross et al. 2009; Godden and Cowell 2016). The IPA program is based on voluntary declarations of Aboriginal-owned land to Australia’s National Reserve System (NRS), where the Traditional Owners are compensated for continued land management per IUCN guidelines (Szabo and Smyth 2003). There are currently 85 dedicated IPAs protecting over 87 × 106 ha, representing more than 50% of the NRS (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water 2024). The program requires Traditional Owners to develop management plans that integrate traditional stewardship with current conservation efforts. This may include objectives and activities such as threatened species monitoring and protection, pest management, protection of cultural sites and knowledge, interpretive activities for visitors, and revegetation. In most cases, the IPA program is complemented by the ‘Working on Country’ and the ‘Indigenous Rangers Programs’ that offer stable, long-term resourcing for many initiatives, particularly the employment of Aboriginal rangers (Mackie and Meacheam 2016). IPAs are highly successful and often result in a raft of socio-cultural, political and ecological benefits (Tran et al. 2020).

In this paper, we focus on the work being conducted within the Nyangumarta Warrarn IPA in relation to research and management of the dingo (Canis dingo), a native free-ranging Australian canid of significant ecological and cultural importance to the Nyangumarta people. We describe the development and successful implementation of an Indigenous-led project focusing on the dingo (hereafter wartaji, the language name for the dingo) that involved a collaboration between rangers and university-based researchers. Such information is important for understanding the dingo’s role in the landscape and making informed dingo management and conservation actions that are culturally appropriate and foster a healthy Country.

The Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area

Nyangumarta Warrarn Country is in Western Australia’s north-western Pilbara and south-western Kimberly region. Nyangumarta people are the Traditional Owners of more than 33,843 km2 of native-title determined lands extending from ~110 km of coastline along Eighty Mile Beach and ~320 km deep into Pirra Country (or The Great Sandy Desert, GSD). Notably, this region holds significant importance for both conservation initiatives and Aboriginal cultural heritage, for example, sacred sites, stories, and songlines that cross the broader region (Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation 2022).

In 2015, Nyangumarta decided to declare an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) of ~28,000 km2 of country encompassing the GSD, including Walyarta Conservation Park, and Kujungurru Warrarn Conservation Park, Kujunguru Nature Reserve, and Eighty Mile Beach Marine Park Intertidal Park along the coastline. The biodiversity and cultural resources of the many habitats within the IPA are managed by the Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (NWAC). NWAC has worked closely with Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation (YMAC) for nearly 20 years, and the partnership continues with the ranger program and its management.

The Nyangumarta rangers are based out of Bidyadanga, a remote Aboriginal Community 180 km south of Broome. The rangers have six part-time staff and a casual pool of 40 rangers, cultural advisors and Elders. The rangers hold return-to-country trips annually for members of the Nyangumarta community who live in other areas, including Broome, Port Hedland, Marble Bar, Yandeyarra, and Warralong. These return to Country trips are integral for knowledge transfer and for the community to be on-Country and provide a cultural governance mechanism for the community to give direct input into management programs.

The current management plan for the IPA spans 2022–2032 (Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation 2022). Their annual work plans contain a component focusing on fauna and flora, whether through opportunistic data collection when rangers are working in the IPA or through specific surveys usually conducted in collaboration with Parks and Wildlife, environmental consulting firms, or conservation organisations.

A meeting of Nyangumarta Traditional Owners, including Nyangumarta rangers and Elders, was held in 2021 at the Bidyadanga ranger base to discuss the work plan of the following year. During this planning, the rangers and community members discussed what was important to learn to better understand the characteristics of a healthy Country. During the meeting, everyone enthusiastically agreed that a priority should be to learn more about the wartaji on Nyangumarta country. They then collectively identified the key areas they wanted to better understand. This included learning more about the wartaji’s behaviour and lifestyle, the role of wartaji in fostering a healthy Country, and how wartaji should be managed and monitored. Specific questions included finding out where on the IPA the wartaji lived, how many wartaji were there, what they ate (diet), and whether there were distinct populations between the west and east of the IPA. Another key question related to how wartaji interact with feral species such as foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and cats (Felis catus), which are present on the IPA and the subject of concern because of their impact on native fauna.

The historical, cultural, spiritual and ecological importance of the dingo

The dingo holds significant cultural and spiritual importance for First Nations peoples across Australia. According to Traditional beliefs, the relationship between dingoes and people has existed since the beginning of time (Creation), and according to science between 5 and 10,000 years (Cairns and Wilton 2016; Zhang et al. 2020). In some areas, the dingo is thought to have played a key role in human origins (Rose 1992). Dingoes regularly feature in Dreamtime, art, ceremony, and songlines as important figures, including as creators and protectors who help establish lore (Smith and Litchfield 2009; Costello et al. 2021). In fact, the dingo is among the most represented animals in the Dreamtime (Kolig 1973).

Dingoes are considered family or kin (Musharbash 2017; Costello et al. 2021), often receiving skin identities/names and burials in the same manner and place as human burials (Smith and Litchfield 2009; Koungoulos et al. 2023). There are several examples where the dingo is a sacred totem (Rose 1992; McIntosh 1999).

At various times, dingoes have served many practical roles, including aiding hunting activities (Koungoulos and Fillios 2020), assisting in finding water, particularly in desert landscapes (Philip 2021), as guardians and protectors (both in the living and spiritual world), campsite cleaners, as a source of warmth, and as loved companions (Smith and Litchfield 2009). A clear distinction was often given between dingoes that were free living (or wild) and those that were tame (or camp companions) (Smith 2015). The deep relationship continues today, with canids of all types being considered an important and positive part of many communities across Australia (Meehan et al. 1999; Musharbash 2017; Ma et al. 2020).

Despite the clear significance of dingoes to Aboriginal cultural heritage values, First Nations peoples are often excluded from their management and protection. The involvement of Aboriginal people in dingo management continues to be controversial and problematic (Carter et al. 2017; Costello et al. 2021). To begin changing this, a First Nations dingo forum was held in 2023 to discuss the dingo, its place in legislation and current management practices (Girringun Aboriginal Corporation 2023). The forum, a first of its kind, was organised by the Girringun Aboriginal Corporation and included representations of more than 20 First Nations groups, including the Nyangumarta rangers. An outcome of the forum included a strong declaration that reinforced (among other things) the importance of the dingo to First Nations peoples and for maintaining a healthy Country (where healthy Country requires the presence of dingoes, which in turn positively influences human health and wellbeing; see Cameron 2020), as well as their desire and right to maintain their cultural obligations to protect the dingo (Lu 2023). The need to work with all stakeholders to find management approaches that ‘strike a balance between safeguarding human interests, preserving the vital ecological role that dingoes perform, and respecting First Nations’ culture’ (Ritchie et al. 2023, see ‘Working and walking together’ section) was also recognised.

The relationship between the Nyangumarta people and wartaji mirrors that of First Nation peoples around Australia. The Nyangumarta people believe that the wartaji have always lived alongside them, and are deeply entwined with their people spiritually and practically as protectors, hunting assistants and companions. Wartaji are also considered environmental protectors, helping maintain ecological balance in the Great Sandy Desert region. Their presence is seen as integral to, and a symbol of a healthy Country. This relationship and connection were summarised by senior Nyangumarta ranger and co-author, Augustine Badal, as follows:

Dingo be here all the time in Australia. Had a relationship with Aboriginal people in Dreaming and is a spirit animal – a companion and a totem for people. The old people all say they had dingoes when they were living in the desert. They used dingo for hunting and as pets. Always together. They protect the land and watch it. Dingo is a sign of healthy Country. They can get rid of cats. They are a friend. They can protect people and warn a family group of other people coming and keeping other dingoes away. They can chase away spirits and beings. Old people used to feed them the same feed they ate.

The wartaji feature in many Nyangumarta Dreamtime stories, including the one provided below as told by a senior Nyangumarta man. This Dreamtime parable shows that wartaji were not just a companion and helpers (for finding food and water), but an intellectual leader and teacher, and showing how humans inherited their roles and knowledge from the wartaji. The story also emphasises the cultural responsibility of the Nyangumarta people to care for the wartaji and all their canine descendants and relatives.

A Nyangumarta wartaji story

One day, we decided to visit an old bloke in our community. We were having something to eat, and all these dogs were coming around begging for food. We began shooing them away giving them a hiding. Observing this, the old person said ‘Oh don’t do that, don’t do that. Treat them right way. That animal he was like you in the Dreamtime’.

Wartaji has always been an important animal. In earlier days when they were walking around, they always had wartaji with them. In those days, the wartaji was the master. Very important from the beginning. In general, wartaji was the one who gathered the food when people depended on wartaji for food and to find water. Wartaji always knew where the water was. The wartaji was smarter than the humans. The wartaji was the brains, and the human was the one who did the running, chasing, and gathering. The wartaji in that situation would give orders, such as to get some wood. And the human would take off and get some wood. Get a kangaroo, and the human would run off (fast) and return with a kangaroo. The human would obey the wartaji, and would share food, water, honey, and everything with them.

Humans and wartaji have always been together, but their roles have changed. The wartaji said ‘You have been loyal all this time, and you never disobeyed me. You did everything exactly as I told you. So now I will give you my brain, my knowledge, and you’ll become exactly like me’. The wartaji instructed the human to make a big fire. ‘You gotta kill me, and when you kill me, you gotta eat me’. The human agreed, and made a fire. The human got a big club and knocked the wartaji on the head. But before he did that, the wartaji advised: ‘When you cook me and eat me, you gotta eat me from the back end to the head. Because the head has the knowledge, you gotta eat that last. That is still there, and operating even though I might be dead’. And so, the human did just that.

And that’s how we came to be how we are. The human was the one doing the running around, gathering the food, and the dog was the master, ‘cracking the whip’ in the Dreamtime. That’s why the old man said don’t hit that dog. Because he was the one who was the boss, and when we were created, he made you to be become what you are now, today. So, when you see a stray dog down the road, give him something to eat.

Wartaji, contemporary IPA management, and the beginning of a collaboration

The region boasts a rich and diverse array of vertebrate fauna, particularly reptiles and birds (see van Etten 2020; Nou et al. 2021). A number of small-to-medium-sized mammal species have been lost since colonisation, and many, including the bilby (Macrotis lagotis) and black-footed rock wallaby (Petrogale lateralis) are considered threatened or vulnerable to extinction (Bastin and the ACRIS Management Committee 2008; van Etten 2020). The dingo is present across the region and is not considered threatened. Factors posing significant challenges to local biodiversity and ecosystem health include invasive predators such as feral cats, foxes, and feral camels (Camelus dromedarius), excessive grazing, and changes in fire regimes (Woinarski et al. 2015; van Etten 2020).

Within the IPA, wartaji are largely left unmanaged. Even though only ~7% of the GSD bioregion is grazed with cattle (Bastin and the ACRIS Management Committee 2008), the IPA shares boundaries with three pastoral stations (Anna Plains Station, Wallal Station and Mandora Station) that actively undertake lethal control of wartaji by poison-baiting and trapping. Wartaji are regularly observed within the Nyangumarta Warrarn IPA through ad hoc observations, and during regular fauna and flora surveys (e.g. 2-ha track plots and remote-sensor cameras) focused on species such as jirrartu (bilby) and karapulu (black-footed rock wallabies). However, no formal wartaji survey has been conducted. As a result, the status, population, distribution and behaviour of wartaji within the IPA are largely unknown.

A focus on wartaji fosters a greater understanding of its role in the landscape, aids in the understanding of a healthy Country, and upskills rangers in scientific approaches to studying wildlife. At the same time, it encourages discussions around the cultural importance of the wartaji. Such information is important for making informed management and conservation decisions that reflect many of the key Nyangumarta values relating to managing Country as outlined in the current IPA ‘Plan of Management’ (Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation 2022). Such values include preserving Marrngumili (Law and Culture), caring for Country, and applying and sharing their extensive knowledge and spiritual connection with Pirra Country.

The IPA ‘Plan of Management’ sets out the overarching values, strategies and programs, which are implemented through annual work plans. Each year, the rangers, with advice from their Elders and the IPA Advisory Committee, develop and then conduct this work plan. A wartaji-specific work plan was subsequently developed for the 2022/2023 season, which detailed the actions (‘to commence fieldwork with wartaji experts’), and the desired outcomes (‘to tabulate preliminary findings and investigate future steps for a long-term wartaji study’). This work plan relates to several programs outlined in the Plan of Management (Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation 2022). Primarily, wartaji-focused activities directly address Program 4 (Native Plants and Animals), which purports to ‘Continue to work with partners to build knowledge of threatened species and ecological communities over time in Pirra Country to ascertain the health of Country and impact of management regime (e.g. long-term biodiversity sites)’. However, it relates indirectly to several other programs, including Program 5, ‘Capability and capacity building’, where IPA rangers are developing specialised skills; Program 1, ‘Cultural and natural heritage management’, where the goal is to document language stories and songs in relation to wartaji; and Program 6, ‘Feral animal and weed management’, which explores the relationship between wartaji and cats.

Responding to the community-led discussions and priorities, the YMAC program manager invited researchers from Central Queensland University to collaborate and help establish a wartaji project. This partnership was sought as the rangers recognised the need to bridge their traditional ecological knowledge with modern scientific methods. This strategic engagement with university-based researchers not only empowered the rangers to enhance their conservation practices but also ensured that they played a central role in shaping the direction and objectives of the project. Early discussions between researchers and IPA management (program coordinators, IPA coordinator, and ranger coordinator) were used to develop the aims and scope of the program, which included taking into account the feasibility of such goals (e.g. budgets, timelines, and deliverables).

The final project involved a short camera-trapping-based survey to establish a baseline of information on which to build. After a proposal was agreed on, a memorandum of understanding and consultancy contract was developed and signed by all parties. The IPA covered much of the on-ground logistics (remote-sensor cameras, vehicles, fuel, food, ranger salaries) as part of their operations budget. Salaries from researchers were provided in-kind, and a small budget was agreed for project costs to cover researcher travel, research assistants, DNA and diet analysis, and consumables (batteries, memory cards etc.). The remainder of this paper presents the details and outcomes of this scoping study.

The wartaji project

The project aimed to begin developing an understanding of dingoes residing within the Nyangumarta Warrarn IPA. It focused on establishing indicators of dingo habitat use, population dynamics, ecology, genetics, and diet, and examining interactions with feral cats and foxes. To do this, a 12-month study was developed, focusing on a comprehensive array of remote-sensor cameras, combined with target searches for wartaji scats, observations of signs and traces, and collection of genetic material using hair traps and ad hoc collection of biological samples. This took place over three field trips, lasting ~3–4 days in duration, plus additional ad hoc activities conducted by the rangers across the year.

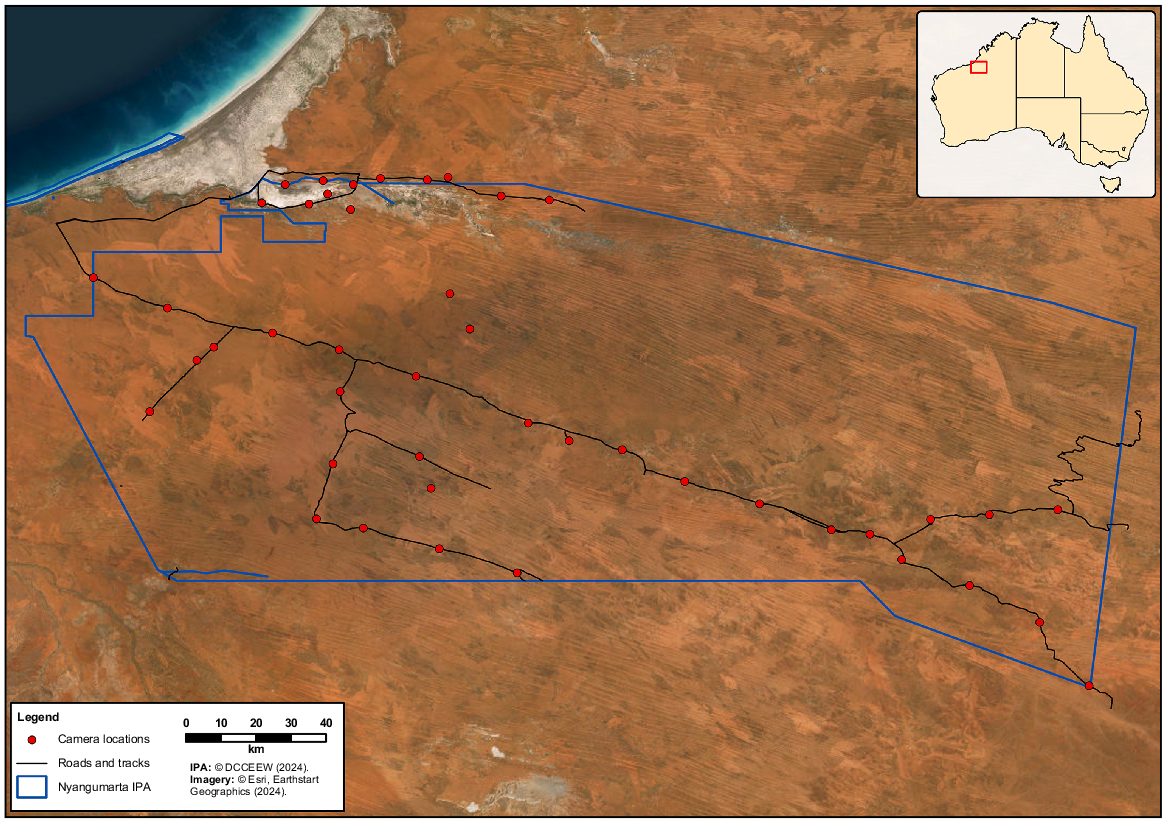

The placement of cameras and data-collection points (for audio recording, and scat collection) were pre-determined by the research team (see Fig. 1). Initial camera-trap arrays based on best practice, had to be modified during the planning stage after consultation with the rangers and IPA advisory committee, indicating several logistical issues (mostly concerning access and travel time to proposed sites). Approval to conduct the research was granted by the CQUniversity Animal Ethics Committee (number 23633), and a licence obtained to use animals for scientific purposes from the Government of Western Australia (licence number U227/ 2022-2024).

A satellite image of the Nyangumarta Warrarn IPA, detailing dirt tracks, and the location of data-collection points.

There were several challenges and factors that helped shape the scope and scale of the project. As mentioned, very little information about the Nyangumarta wartaji population was available. In fact, there have been few studies on wartaji conducted in similar desert habitats (Great Sandy Desert bioregion). A handful of research has been conducted in the surrounding area, but centred around anthropogenic activities such as mining operations (e.g. Smith and Vague 2017; Smith et al. 2019, 2020). A major exception is the impressive body of work conducted by Peter Thomson in Fortescue River (located south-west of the IPA in the Pilbara region) in the early 1990s (Thomson 1992a, 1992b, 1992c, 1992d; Thomson et al. 1992a, 1992b). This is why it was important to conduct a baseline covering a 12-month period to account for seasonal variations and to make as few assumptions as possible about the local wartaji and our approach to their study (e.g. home-range size, family group size, activity schedules, movement patterns). Such an approach enables the detection of any localised differences that may exist.

Accessing the IPA is challenging, owing to its size (it covers more than 28,000 km2), remoteness (located 4 h south of Broome, and 2 h from the nearest community of Bidyadanga), diverse habitats (Great Sandy Desert bioregion, Canning basin, and wetlands and freshwater springs), and limited infrastructure (limited water sources, and access tracks providing limited access to many parts of the IPA). The Nyangumarta Highway (previously referred to as Kidson Track and Wapet Road), is the only east–west unsealed access dissecting the IPA for ~310 km. Other key dirt roads provide limited access to other parts of the IPA, but most areas can be reached only by air (Fig. 1). Unpredictable and harsh weather presents a further challenge, with fieldwork being typically restricted to the period between April and November owing to the wet season. Logistics were further challenged when factoring in ranger rosters that are typically only four successive days (Monday–Thursday), including associated travel time to and from the IPA.

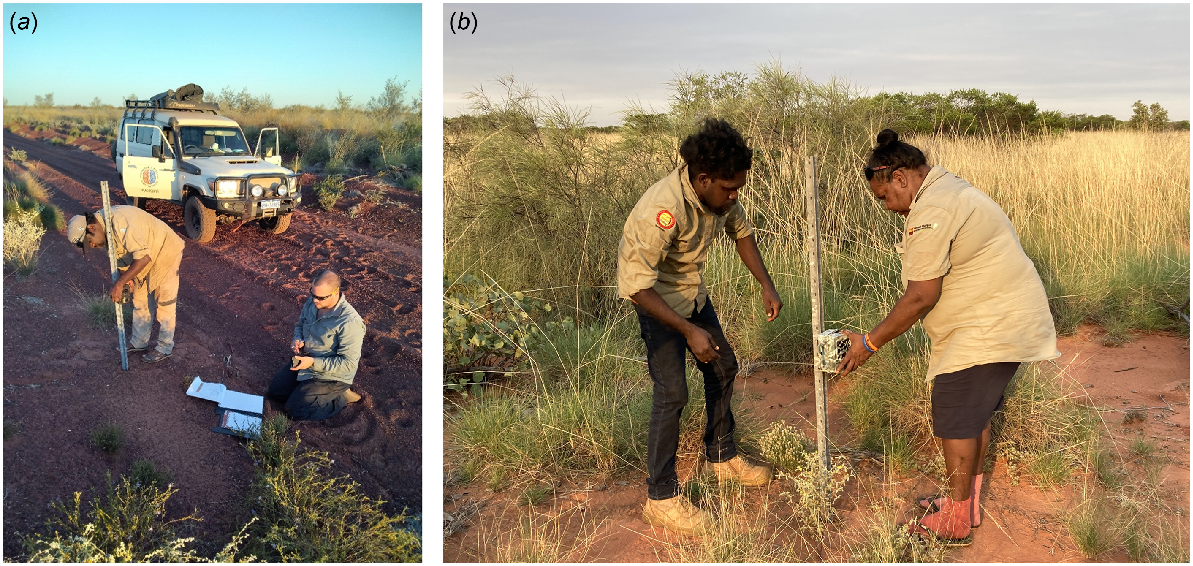

Key to the project was upskilling the Nyangumarta rangers, equipping them with the necessary tools and knowledge to undertake camera-trap surveys, audio recording, observational surveys, and DNA collection (Fig. 2). Additionally, the project facilitated two-way learning, merging cultural and scientific knowledge to inform wartaji management and conservation plans. Last, the project intended to establish a relationship among the research team, Nyangumarta IPA rangers and the community, so as to support an ongoing program focused on the wartaji.

Outcomes, future directions and opportunities

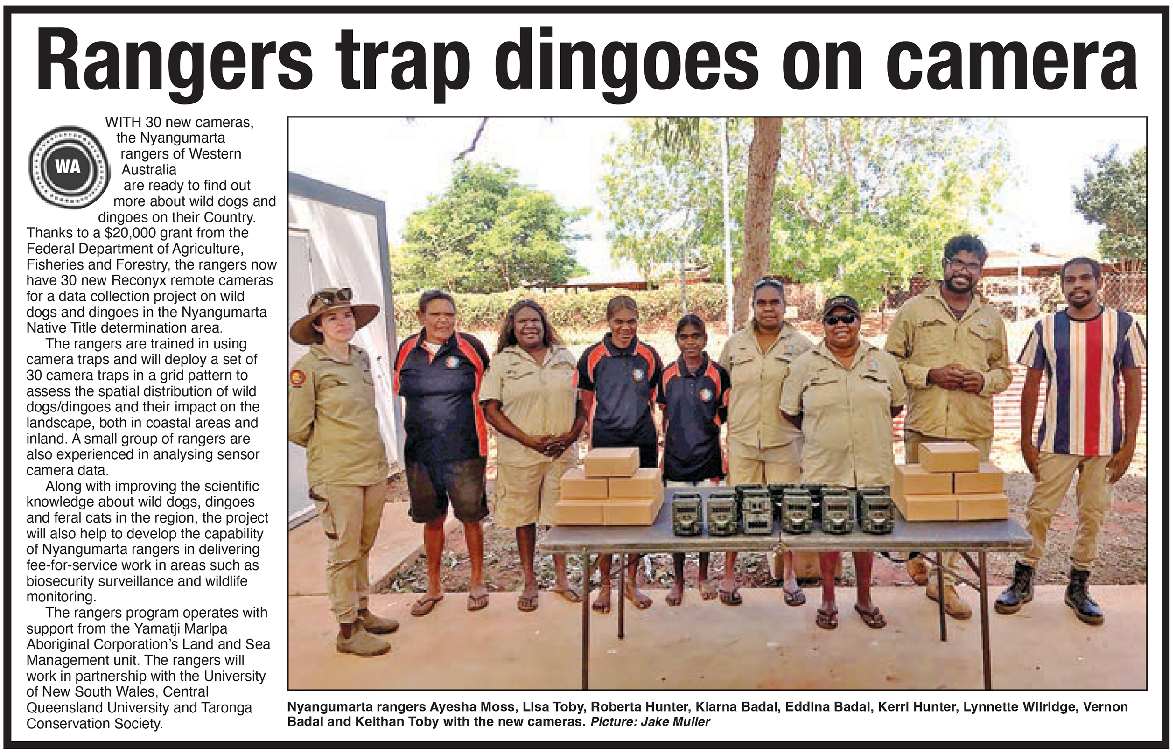

The wartaji project is still in its early stages, yet an intensive year of data collection has already yielded significant outcomes and met project goals and initial work-plan objectives (Fig. 3). Camera-trapping surveys present a suitable approach for baseline studies, given high detectability scores, and what data can be extracted from such detections (e.g. identification, location, activity). During the project, strong relationships have been established, and rangers have been upskilled in various methodologies, including setting up cameras and audio recorders, and enhancing record-keeping and management practices. Additionally, this initial phase has provided a solid baseline understanding of the wartaji population, diet and behaviour, which will serve as a foundation for future research and conservation efforts. Findings from the project will be reported elsewhere.

The wartaji project has received positive media attention in a national Indigenous newspaper (Koori Mail, 19 October 2022, p. 10).

The following quotations from an IPA ranger, ranger coordinator, and the Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation illustrate the success of the wartaji project and collaboration:

Was real good to go and see all of the IPA and check up and learn about dingoes. Great to work with the scientists and showing them Country. Showing them what rangers do. Good to go and try new areas with the cameras. To show them the sites and look for tracks and scats. Dingoes been around forever used for hunting, tracking all of that. When I see dingo on Country it makes me feel happy to see them. Hope to learn more about them and good to see they taking care of the cats. [Elliot Hunter, Nyangumarta Ranger]

Being involved in this ranger/community-led project has been fantastic. Seeing the ranger team take ownership as the project developed and to share their knowledge with other groups hopefully will lead to more Indigenous-led science projects and increase our collective knowledge about dingoes. [Jake Muller, Nyangumarta Ranger Coordinator]

In their ongoing commitment to studying and preserving wartaji, the Nyangumarta rangers will continue to systematically and opportunistically gather information, for example, by maintaining their extensive camera-trapping network, collecting wartaji scats for dietary analysis, and obtaining biological samples (e.g. bones, and DNA material) when possible. These activities, along with maintaining accurate records, are fundamental to building a comprehensive wartaji database, which is crucial for future research and for developing and evaluating management strategies. The rangers aim to disseminate their findings in culturally appropriate ways for the Nyangumarta community, other IPA ranger groups, and to the scientific community, to enhance awareness and understanding of wartaji and their work. The Nyangumarta people are well placed to contribute to our understanding of wartaji in this bioregion.

Looking ahead, the IPA has numerous opportunities to expand its research and collaborations. The rangers prioritise developing a long-term wartaji-monitoring framework. They seek to create evidence-based management and conservation plans that focus on the cultural significance of wartaji, assess the impact of invasive species, and protect threatened species. A major initiative planned for the near future involves equipping wartaji with GPS collars to monitor their movements and behaviours. Such activities will continue strengthening the ties between academic institutions and practical conservation efforts. Expanding this tracking to include interactions among wartaji, foxes, and cats could provide valuable insights essential for managing these species and protecting threatened local wildlife (Fig. 4).

A wartaji was captured holding a dead cat in its mouth. Insights such as these, and from diet analysis, are vital for understanding the dynamics between wartaji and introduced predators.

The IPA plans to extend its research network by partnering with neighbouring IPAs and engaging with local pastoralists. This expansion aims to broaden the scope of the study and foster cooperative wildlife management strategies, potentially reducing reliance on lethal control methods and towards the use of non-lethal approaches. Initiating discussions with local mining companies is also important, because this could lead to new employment opportunities for the community in areas such as wartaji management (e.g. mitigating wartaji–human conflict) and educational roles.

The rangers are particularly enthusiastic about involving their community more deeply in their conservation efforts. They encourage local schools to participate in ‘citizen science’ projects, which could include activities such as analysing camera-trap data, tracking wartaji using satellite collars, and participating in naming and studying individual dingoes. Local art competitions may encourage storytelling and the personal connection by the community towards wartaji. This approach not only encourages the recording of cultural knowledge and histories but also fosters a deeper connection between the community and wartaji.

To sustain these initiatives, the IPA will actively seek funding from a range of sources, including local mining companies and research grant opportunities. With the necessary financial support, they can continue integrating scientific research with traditional knowledge and practices, thereby enhancing the conservation of wartaji and the community’s engagement with this iconic culturally significant species.

Conclusions

The wartaji project exemplifies the effectiveness of Traditional owner-led conservation and ecological research, highlighting the cultural and ecological significance of wartaji. This initiative was designed to expand knowledge within the community and build the capacities of local rangers for long-term management. The collaboration with academic and non-academic researchers promise to enhance this conservation effort through mutual learning, showing the value of combining traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches. The success of such projects underscores the importance of IPAs and Indigenous Rangers Programs, which are vital for facilitating these effective partnerships and sustaining conservation efforts.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Declaration of funding

The project was funded by the Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation, with in-kind contributions from CQUniversity and Taronga Conservation Society.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Nyangumarta ranger coordinators Jake Muller, Ayesha Moss, and Jessica Bolton, as well as Dr Ben Pitcher from Taronga Conservation Society and Brendan Alting from the University of New South Wales, for assisting with the project logistics and fieldwork. We acknowledge the Nyangumarta People as the Traditional Owners of the land on which this research was conducted. We respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners and custodians throughout Western Australia, and on whose Country we work. We acknowledge and respect their deep connection to their lands and waterways. We honour and pay respect to Elders, and to their ancestors who survived and cared for Country. We recognise the continuing culture, traditions, stories and living cultures on these lands and commit to building a brighter future together.

References

Cairns KM, Wilton AN (2016) New insights on the history of canids in Oceania based on mitochondrial and nuclear data. Genetica 144(5), 553-565.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cameron L (2020) ‘Healthy Country, Healthy People’: Aboriginal Embodied Knowledge Systems in Human/Nature Interrelationships. The International Journal of Ecopsychology 1(1), 3 Available at https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/ije/vol1/iss1/3.

| Google Scholar |

Carter J, Wardell-Johnson A, Archer-Lean C (2017) Butchulla perspectives on dingo displacement and agency at K’gari–Fraser Island, Australia. Geoforum 85, 197-205.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Costello O, Webster N, Morgan D (2021) A statement on the cultural importance of the dingo. Australian Zoologist 41(3), 296-297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2024) Indigenous Protected Areas. Available at https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/land/indigenous-protected-areas#toc_0 [accessed 1 May]

Girringun Aboriginal Corporation (2023) National Inaugural First Nations Dingo Forum. Available at https://www.girringun.com/dingoforum2023 [accessed 15 May 2024]

Godden L, Cowell S (2016) Conservation planning and Indigenous governance in Australia’s Indigenous Protected Areas. Restoration Ecology 24(5), 692-697.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kolig E (1973) Aboriginal man’s best foe. Mankind 9, 122-124.

| Google Scholar |

Koungoulos L, Fillios M (2020) Hunting dogs down under? On the Aboriginal use of tame dingoes in dietary game acquisition and its relevance to Australian prehistory. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 58, 101146.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Koungoulos LG, Balme J, O’Connor S (2023) Dingoes, companions in life and death: the significance of archaeological canid burial practices in Australia. PLoS ONE 18(10), e0286576.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lu D (2023) First Nations groups demand immediate stop to killing dingoes as control method. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/18/first-nations-groups-demand-immediate-stop-to-killing-dingos-as-control-method

Ma GC, Ford J, Lucas L, Norris JM, Spencer J, Withers A-M, Ward MP (2020) ‘They Reckon They’re Man’s Best Friend and I Believe That.’ Understanding relationships with dogs in Australian Aboriginal communities to inform effective dog population management. Animals 10(5), 810.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mackie K, Meacheam D (2016) Working on country: a case study of unusual environmental program success. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 23(2), 157-174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McIntosh IS (1999) Why the dingo ate its master. Australian Folklore 14, 183-189.

| Google Scholar |

Meehan B, Jones R, Vincent A (1999) Gulu-kula: dogs in Anbarra Society, Arnhem Land. Aboriginal History 23, 83-106.

| Google Scholar |

Musharbash Y (2017) Telling Warlpiri dog stories. Anthropological Forum 27(2), 95-113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation (2022) ‘Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area, Plan of Management, 2022–2032.’ (YMAC, Inc.) Available at https://www.ymac.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Nyangumarta-Warrarn-IPA-2022-single-low-res-002.pdf

Philip J (2021) The waterfinders. A cultural history of the Australian dingo. Australian Zoologist 41(3), 593-607.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ritchie E, Smith B, Cairns K, Takau S, Rassip W (2023) ‘The boss of Country’, not wild dogs to kill: living with dingoes can unite communities. In The Conversation, 2 October 2023. Available at https://theconversation.com/the-boss-of-country-not-wild-dogs-to-kill-living-with-dingoes-can-unite-communities-214212

Ross H, Grant C, Robinson CJ, Izurieta A, Smyth D, Rist P (2009) Co-management and Indigenous protected areas in Australia: achievements and ways forward. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 16(4), 242-252.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith BP, Litchfield CA (2009) A review of the relationship between indigenous Australians, dingoes (Canis dingo) and domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Anthrozoös 22(2), 111-128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith B, Vague A-L (2017) The denning behaviour of dingoes (Canis dingo) living in a human-modified environment. Australian Mammalogy 39, 161-168.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith BP, Vague A-L, Appleby RG (2019) Attitudes towards dingoes (Canis dingo) and their management: a case study from a mining operation in the Great Sandy Desert, Western Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 25, 308-321.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith BP, Morrant DS, Vague A-L, Doherty TS (2020) High rates of cannibalism and food waste consumption by dingoes living at a remote mining operation in the Great Sandy Desert, Western Australia. Australian Mammalogy 42(2), 230-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smyth D (2006) Indigenous protected areas in Australia. Parks 16(1), 14-20.

| Google Scholar |

Szabo S, Smyth D (2003) Indigenous Protected Areas in Australia – Incorporating Indigenous owned land into Australia’s national system of protected areas. In ‘Innovative Governance – Indigenous peoples, local communities and protected areas’. (Eds H Jaireth, D Smyth) pp. 145–164. (Ane Books: New Delhi, India)

Thomson PC (1992a) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. I. The Fortescue River study area and details of captured dingoes. Wildlife Research 19, 509-518.

| Google Scholar |

Thomson PC (1992b) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. II. Activity patterns, breeding season and pup rearing. Wildlife Research 19, 519-530.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomson PC (1992c) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. III. Hunting and feeding behaviour, and diet. Wildlife Research 19, 531-542.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomson PC (1992d) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. IV. Social and spatial organisation, and movements. Wildlife Research 19, 543-564.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomson PC, Rose K, Kok NE (1992a) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. VI. Temporary extraterritorial movements and dispersal. Wildlife Research 19, 585-596.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomson PC, Rose K, Kok NE (1992b) The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia. V. Population dynamics and variation in the social system. Wildlife Research 19, 565-584.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tran TC, Ban NC, Bhattacharyya J (2020) A review of successes, challenges, and lessons from Indigenous protected and conserved areas. Biological Conservation 241, 108271.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

van Etten EJB (2020) The Gibson, Great Sandy, and Little Sandy Deserts of Australia. In ‘Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes’. (Eds MI Goldstein, DA DellaSala) pp. 152–162. (Elsevier) doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11967-0

Woinarski JCZ, Burbidge AA, Harrison PL (2015) Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(15), 4531-4540.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zhang S-J, Wang G-D, Ma P, Zhang L-L, Yin T-T, Liu Y-h, Otecko NO, Wang M, Ma Y-P, Wang L, Mao B, Savolainen P, Zhang Y-P (2020) Genomic regions under selection in the feralization of the dingoes. Nature Communications 11(1), 671.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |