Establishing protocols to apply repellents while hazing crop pests: importance of habitat, flock size, and time on blackbird (Icteridae) responses to a drone capable of spraying

Mallory G. White A , Jessica L. Duttenhefner A and Page E. Klug B *

B *

A

B

Abstract

Drones can be used as frightening devices to resolve avian-agriculture conflicts. Blackbird (Icteridae) flocks respond to drones making them a suitable scare device to protect sunflower (Helianthus annuus), but with limited efficacy on large flocks. Integrating a non-lethal avian repellent on the same drone as used for hazing may increase efficacy, but responses of flocks towards drones with spraying capabilities need to be evaluated to inform application protocols.

We evaluated flock responses to a drone capable of spraying when first approached and with 10 min of hazing, to inform protocols for delivering repellents on agricultural landscapes.

We used eye-in-the-sky drones to video the drone with spraying capabilities and observed whether flocks took flight within 80 m (i.e. range of potential spray drift). We measured flight initiation distance (FID) when close approach occurred (i.e. drone ≤80 m from flock). While hazing, we piloted the drone to (1) repeatedly cut through a flock and create chaos or (2) move along the flock edge to herd birds out of target habitat (i.e. sunflower or cattail). We recorded abandonment, flock reduction, and return rate of birds in response to drone hazing.

The probability of a close approach was greater with birds in cattail than in sunflower, but habitat did not influence mean FID when the drone was within 80 m (FID = 40 m ± 14.3 s.d.), abandonment (31 of 60 flocks), or mean percentage flock reduction (50% ± 37 s.d.). FID was shorter with smaller flocks, later in the day, but abandonment increased with smaller flocks as the day progressed. Although 52% of flocks abandoned, 81% returned after the end of hazing. Flight path of the drone (i.e. chaotic or herding) did not affect abandonment or flock reduction.

Although blackbirds perceived the drone approach as riskier (>FID) while foraging in sunflower earlier in the day, increased abandonment that occurred later in the day was likely to be due to satiation and movement to night-time roosts, instead of hazing impacts. Birds in sunflower interspersed with cattail used local refugia until the threat passed, then resumed foraging.

If applying an avian repellent with a spraying drone, protocols should consider time of day, flock size, and habitat. When selecting a flight path, pilots need to be concerned only with optimizing spray drift to reach areas with foraging blackbirds.

Keywords: antipredator behavior, crop damage, deterrent tools, human–wildlife conflict, remotely-piloted aircraft systems, UAS, UAV, vertebrate pests, visual deterrent.

Introduction

In crop production, profit loss owing to bird damage is prevalent across the globe, affecting a variety of agricultural sectors, including viticulture, horticulture, and other cropping systems (Conover 2002; Tracey et al. 2006). The nuisance bird differs depending on region, location, and/or crop, but blackbirds (Icteridae) are known to damage crops across North America (Shwiff et al. 2017). In sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), direct production losses reach US$3.5 million annually in North Dakota (Klosterman et al. 2013), whereas the additive impacts of indirect loss extend to US$18 million when considering local economies (i.e. impact of change in one sector on regional revenue and jobs) and the labor and time spent managing the issue (Ernst et al. 2019).

At the same time, blackbirds are a protected, native family of birds facing overall population declines of ~1% annually. Although red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) populations vary geographically, some regions, such as the northern Great Plains, are experiencing 1.5% annual population increases (Rosenberg et al. 2019; Sauer et al. 2019), along with significant conflicts with agriculture. Landscapes with wetlands dominated by cattails are preferred by blackbirds during the breeding season and as roosting habitat during fall molt and migration (Linz et al. 2003; Forcey et al. 2015). Blackbirds can travel 8–10 km from their night-time roost to forage; thus, sunflower fields with cattail marshes nearby or imbedded within the field suffer higher crop damage (Dolbeer 1990; Homan et al. 2005; Dolbeer and Linz 2016). In North Dakota, cattail roosts can host >1 million migrating blackbirds in the fall, causing significant damage to nearby crops (Clark et al. 2020).

Methods to mitigate damage caused by blackbirds are implemented at multiple spatial scales, but tools at the field scale are the most accessible and most frequently used by farmers (White 2021). However, current field-scale options (e.g. exclusion methods, frightening devices, habitat manipulation, and chemical repellents) are limited in terms of efficacy, range, feasibility, or cost (Sausse et al. 2021; Klug et al. 2023; Duttenhefner and Klug 2024). In situations of commercial agriculture, stationary field-based tools (e.g. propane cannons or scarecrows) are not sufficient to move large flocks out of large fields and birds are often tolerant of the tools. Thus, dynamic, mobile tools are needed and may require the integration of multiple tools to increase efficacy (Klug 2017).

Drones are dynamic, highly mobile, and show promise for use in human–wildlife conflicts (Hahn et al. 2017; Penny et al. 2019; Chilvers 2024). Managers of small-scale agriculture systems such as vineyards, rice paddies (Oryza spp.), and aquaculture ponds have deployed drones to detect and harass nuisance birds (Burr et al. 2019; Rhoades et al. 2019; Mohamed et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). In controlled aviary settings, drones elicit antipredator alert and escape responses by individual male, red-winged blackbirds (Wandrie et al. 2019; Egan et al. 2020). However, there is proven difficulty in drones producing a consistent abandonment response when hazing blackbird flocks in open agricultural landscapes (i.e. flock and field size impact success; Egan et al. 2023). Increasing the negative stimulus associated with drones, to affect a greater proportion of the flock, may increase abandonment rates. Suggestions have included emitting frightening acoustics (Wang et al. 2019), coordinating a fleet of swarming drones (Paranjape et al. 2018), designing drones to resemble predators (Egan et al. 2020), and deploying an avian repellent from a spraying drone (Ampatzidis et al. 2015; Duttenhefner 2023).

A spraying drone could be used to haze birds, while simultaneously applying an avian repellent to spot-treat areas being actively damaged by birds. Non-lethal repellents are classified as primary repellents if the chemical irritates peripheral chemical senses to initiate a reflexive withdraw (e.g. methyl anthranilate), and as secondary repellents if ingestion results in gastrointestinal irritation and learned avoidance (e.g. anthranilate; DeLiberto and Werner 2024). Traditionally, avian repellents registered for foliar application are applied once a season, on entire fields, by using an airplane or high-boy sprayer, which is expensive, not responsive to the timing of bird damage, and subject to limits imposed by crop structure (Werner et al. 2005; Kaiser et al. 2021). Delivery of an avian repellent via drone may increase direct contact with the chemical owing to real-time application and allows fields to be spot-treated multiple times, effectively reducing chemical costs (Duttenhefner et al. 2024). Although not tested in this study, the application of an avian repellent may increase hazing efficacy.

Prior to conducting studies on the efficacy of hazing blackbird flocks with a drone that also sprays an avian repellent, we need to establish best practices for approaching flocks and how perceptions of risk and responses to drones vary in relation to flock characteristics, habitat, environmental conditions, and drone hazing paths. Flock responses to a drone capable of spraying an avian repellent inform future approach protocols by (1) indicating whether the spraying drone can approach within range of the spray drift, and if within range, how close; and (2) identifying the baseline capability of the spraying drone to elicit abandonment and flock reductions without chemicals. We can minimize variation in future research by selecting one hazing approach (i.e. herding or chaos), understanding implications of avoiding cattail areas while spraying, and identifying ecological factors that confound tool efficacy. With this knowledge, we can establish protocols to effectively deliver repellents by using the same drones as used for hazing. The blackbird–sunflower conflict in North Dakota, USA, is a case study for evaluating flock responses to drones capable of spraying avian repellents (Klug 2017).

We evaluated the probability of being able to approach flocks within 80 m (i.e. range of potential spray drift; Duttenhefner 2023) and, if a close approach occurred, the flight initiation distance (FID) of free-ranging, blackbird flocks to a drone with spraying capabilities. FID is the measurable distance between a bird and an approaching object at the moment the bird decides to take flight (Cooper and Blumstein 2015), and is often used as a behavioral metric to determine how threatened birds are by an approaching object. Many factors influence FID, including habitat, group size, hunting pressure, approach angle, and speed (Fernández-Juricic et al. 2002; Cooper and Blumstein 2015; Egan et al. 2020; Lunn et al. 2022). The flock, habitat, landscape, and environmental variables that influence FID may differ from those influencing behavior during extended hazing. FID is a snapshot of perceived risk of an approaching threat, whereas extended hazing affects risk perception over time.

We evaluated variables influencing FID of blackbird flocks in sunflower–cattail habitat complexes when approached directly by a drone and the probability of abandonment and flock reduction when hazed by a drone. We predicted that larger flocks would react to the approaching drone at greater distances (Egan et al. 2023), given this trend was also seen in waterbirds when approached on foot and by drone (Laursen et al. 2005; Jarrett et al. 2020). We predicted that greater distances between the flock and drone launch site would increase FID, given longer exposure times, and the continual monitoring of an approaching threat is a cost in many bird species (Blumstein 2003; Vas et al. 2015). As shown by Egan et al. (2023), we predicted that smaller field sizes and flock sizes would increase flock abandonment, given the proximity and accessibility of refugia surrounding smaller fields and the behavior of birds in larger flocks (i.e. safety in numbers). We thought pushing the flock may increase abandonment of the habitat, given that repeatedly cutting through the flock may not direct birds out of the sunflower field. Regardless of abandonment, we expected an overall reduction in flock size as a result of drone hazing, as seen in other commodities (i.e. vineyards; Bhusal et al. 2018).

We expected blackbirds to respond to drones differently depending on environmental conditions. Temperature can affect bird behavior, with cold temperatures causing increased metabolic needs; thus, a stronger commitment to food, or heat inducing a stress response (Fernández-Juricic et al. 2002). Wind speed affects drone performance (e.g. speed), but birds may also choose to conserve energy by not flushing or flying during higher winds (Egan et al. 2020). High ambient light reduces detection rates of birds towards an approaching threat, owing to sunlight causing glare effects (Fernández-Juricic et al. 2012). Both habitat types provide refugia through structural safety, but activities (e.g. foraging in sunflower and loafing in cattail) could affect detection and commitment to a location, as seen in the antipredator responses of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) changing with grass height (Devereux et al. 2008). We predicted that flocks located in cattail would have a lower FID and lower abandonment, owing to its function as refugia and the vast area of cattail marshes on the landscape (Bansal et al. 2019). Feeding rates are typically highest in the morning and decline in the afternoon for blackbirds, as foraging needs have been met for the day (Hintz and Dyer 1970); thus, we expected a lower probability of abandonment in the morning than in the afternoon or evening. Last, we included Julian day because it could indicate food availability on the landscape (i.e. increased harvest as season progresses) or a progression towards migration and subsequent caloric needs (Cooper and Blumstein 2015).

Materials and methods

Study design

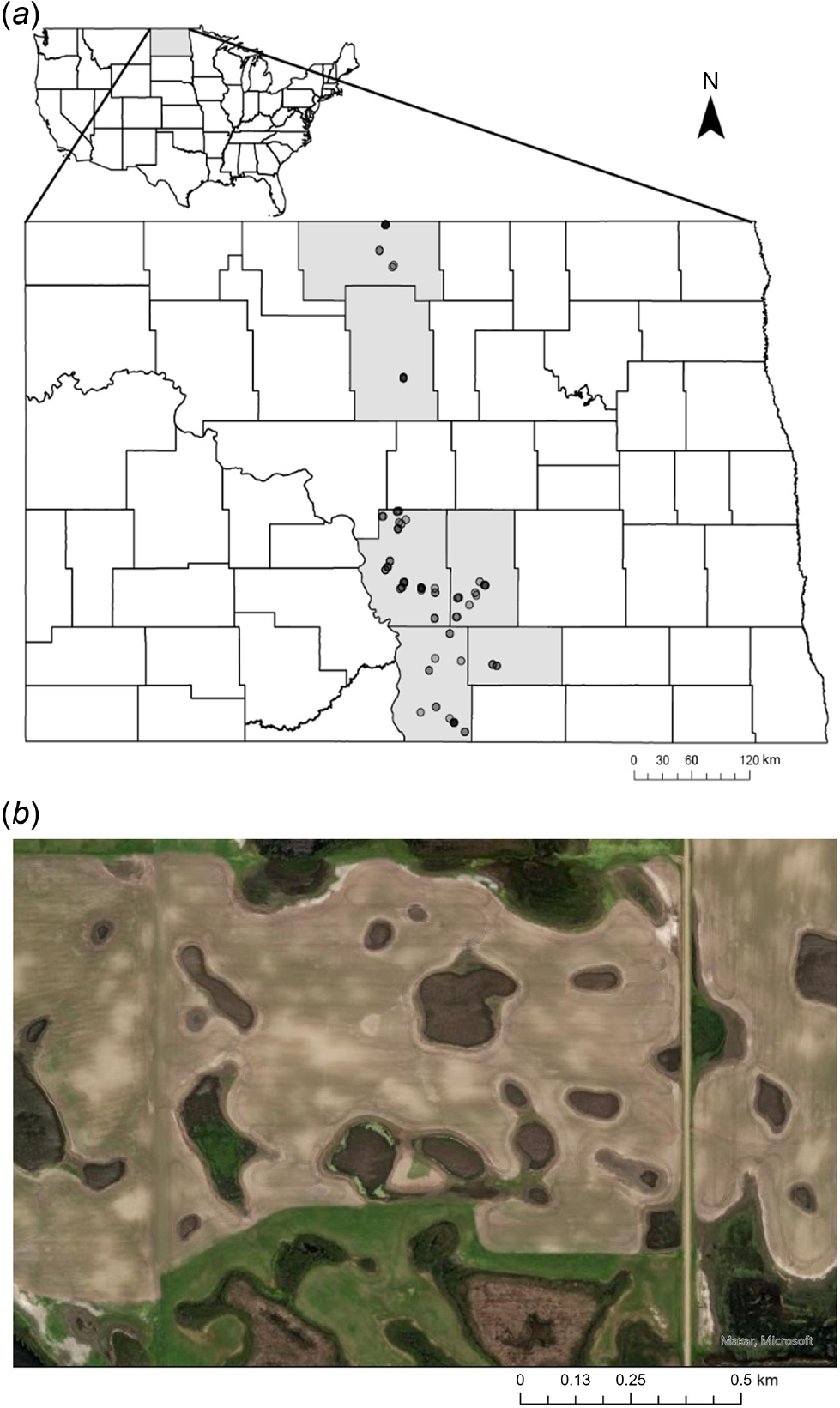

We conducted drone trials in commercial sunflower fields in North Dakota counties experiencing blackbird damage (Bottineau, Burleigh, Emmons, Kidder, Logan, and McHenry; Fig. 1). We targeted locations where blackbird flocks were either actively foraging on sunflower or roosting in cattails within or adjacent to commercial sunflower fields, from 4 September to 25 October in 2019 and 2020, between 07:30 hours and 19:00 hours. We conducted FID trials in both 2019 and 2020, but conducted only hazing trials in 2020.

(a) Trial locations in North Dakota, USA, where we approached and subsequently hazed mixed-species blackbird (Icteridae) flocks with a drone (DJI Agras MG-1P) in sunflower–cattail complexes where sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was being actively damaged, and cattail (Typha spp.) was used as daytime roosting habitat. We conducted 91 trials (2019: FID = 31; and 2020: combined FID and hazing = 60) by using the Agras from 4 September to 25 October (overlap occurs because of scale). (b) An example of a sunflower–cattail complex, where the dark brown and green, irregularly shaped wetlands are within and adjacent to the lighter brown agricultural field (Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community).

Large mixed-species flocks of blackbirds are mainly composed of red-winged blackbirds but also include yellow-headed blackbirds (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus), common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula), brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater), Brewer’s blackbirds (Euphagus cyanocephalus), and European starlings. Cattail marshes are often within or adjacent to sunflower fields in the Prairie Pothole Region of North Dakota, and are used as daytime loafing or refugia sites and night-time roosting sites (Fig. 1). Our study period coincided with the 8-week damage window (ray-petal drop of sunflower up until harvest) when blackbirds are undergoing fall molt and migration (Linz et al. 2017; Stonefish et al. 2021). We considered each blackbird flock as an independent experimental unit, given population turnover with incoming migrant birds and flock mixing at roosting sites resulting in no two flocks being the same over time (Linz et al. 1991). We did not mark flocks; thus, it is possible that individual blackbirds were approached multiple times. If we operated multiple trials at a single field, we allowed an average of 14 days (±9.1 s.d.) between trials in the same year. We conducted hazing trials at 30 fields (12 fields visited once, 11 fields visited twice, three fields visited three times, three fields visited four times, and one field visited five times). We conducted trials evaluating whether flight occurred within 80 m at 46 fields (16 fields visited once, 21 fields visited twice, four fields visited three times, four fields visited four times, and one field visited five times). Sunflower producers practice rotational agriculture; thus, no sunflower fields were repeated in 2019 (16 fields) and 2020 (30 fields). Egan et al. (2023) found that day did not explain significant variation in abandonment during drone hazing; thus, we did not include day as a random factor.

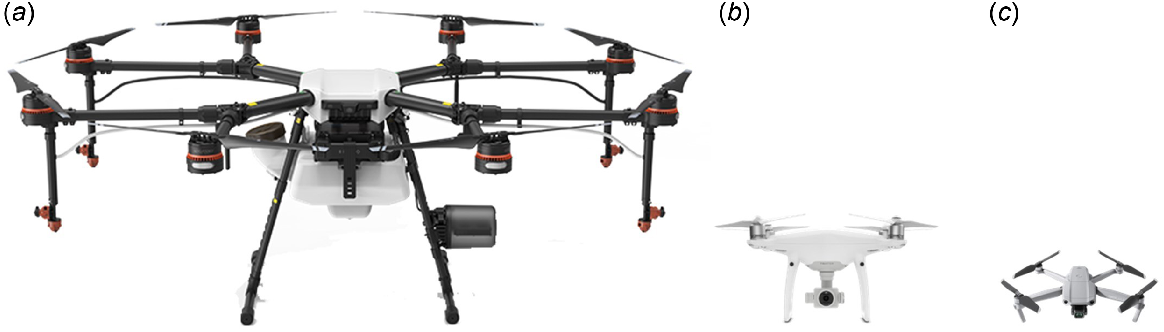

We used a precision agriculture spraying octocopter (DJI AGRAS MG-1P; DJI Shenzhen, China; hereafter, Agras) to approach and haze blackbird flocks (Fig. 2). We used smaller quadcopters (DJI Phantom 4 and DJI Mavic Air 2, DJI Shenzhen, China; Fig. 2) as the eye-in-the-sky drones to video blackbirds responding to the Agras. Wandrie et al. (2019) found no observable impact on flock behavior when flying a drone >60 m above ground level (AGL); thus, we flew the Phantom at 60 m AGL (2019) and the Mavic at 80 m AGL (2020) to increase the field of view. Both eye-in-the-sky drones captured 4K video, but the Mavic was 60 frames s−1 and Phantom 30 frames s−1.

We approached and subsequently hazed mixed-species flocks of blackbirds (Icteridae) with (a) the DJI Agras MG-1P, a drone with spraying capabilities, which has a diagonal length of 1500 mm, a max speed of 15 m s−1, a tank that can hold 10 kg (approximately 9.5 L) of liquid, and has a maximum hovering time of 20 min with an empty tank (9 min with a full tank). We recorded the close approach and flight initiation distance of the Agras by using eye-in-the-sky drones, (b) the DJI Phantom 4, which has a diagonal length of 350 mm, a max speed of 20 m s−1, and a max flight time of ~28 min, and (c) the DJI Mavic Air 2, which has a diagonal length of 302 mm, a max speed of 19 m s−1, a max flight time of ~34 min.

We recorded the habitat where the flock was located (i.e. cattail or sunflower), time of day, Julian day, ambient light (μmol m−2 s−1) with a Li-Cor LI-250 Light Meter and LI-190SA Quantum Sensor (Lincoln Nebraska, USA), temperature (°C) and wind speed (m s−1) with a Skymaster SM-28 weather meter (Speedtech Instruments, Great Falls, Virginia USA). We used Google Earth Pro (ver. 7.3.4.8248, image dates 2016–2020) to measure the area of sunflower and cattail marshes adjacent to or embedded in the crop fields to calculate the size of the sunflower–cattail complexes and the proportion of cattail (Fig. 1). The process for drone trials was (1) a pre-hazing observation period (15 min), (2) drone launch and initial approach (FID), (3) hazing period (10 min), (4) drone landing, and (5) post-hazing observation period (15 min).

FID trials

We began FID trials after the drones reached their designated heights (eye-in-the-sky = 60–80 m AGL; Agras = 5 m AGL). The pilot-in-command and an additional pilot flew both drones manually, with the Agras at the trailing edge of the field of view of the eye-in-the-sky drone. We flew the Agras at a consistent speed (4 m s−1) and height (5 m AGL) in a straightline direction towards the flock until the pilot-in-command visually established that the flock had initiated flight. We used video from the eye-in-the-sky drone to capture whether the flock took flight within 80 m of the drone. If so, we measured straight-line distances between the Agras and the leading edge of the blackbird flock at the moment flight occurred (FID) by using a still frame image in ImageJ (Schneider et al. 2012). We used the known width of the Agras body as the reference for pixel size to calculate distance. We combined the FID distance with the distance the Agras flew while initially approaching the flock to calculate launch distance.

Hazing trials

We began hazing with the Agras after our initial approach to record FID. We continued monitoring the hazing using the eye-in-the-sky drones. We hovered both drones at the FID location and set a stopwatch to assure that every flock received 10 min of hazing. We operated the Agras at variable speeds and altitudes during the hazing period, with the intent of motivating the flock to leave the habitat. We did not have the ability to monitor drone paths (i.e. length, tortuosity, altitude, and speed) because of the technology not being available at the time and scale of the field sites. We hazed flocks by using one of two flight paths, including (1) chaotic (i.e. paths cutting through the flock) or (2) herding (i.e. paths moving along the outer flock edge to move birds towards the nearest exit). We considered hazing successful if an entire flock abandoned the habitat they were occupying for another habitat (i.e. sunflower to any other habitat or cattail to any other habitat). If flocks abandoned the targeted habitat prior to 10 min, we flew the Agras within the habitat near where the flock exited until the end of the allotted time.

We bracketed the hazing period with pre- and post-hazing observation periods (15 min each) to assess percentage flock reduction (number of birds pre-hazing – number of birds post-hazing/number of birds pre-hazing) and whether flocks returned post-hazing. A single observer, who received training via flock estimation simulations and field testing with experts, visually estimated flock size and species composition by using block counting (100–1000 birds) and extrapolation to estimate the number of birds in an aggregation. Although visual estimates of large flocks by human observers are often inaccurate, repeatability of a single observer is moderate; thus, any effect of flock size is a true biological effect (Duttenhefner and Klug 2025). Flock estimates during hazing were not automated with artificial intelligence and machine learning because entire flocks, especially large flocks, were not consistently captured in the field-of-view of the eye-in-the-sky drone, and the difficulty in discerning overlapping, small birds at far distances on a complex vegetative background (Duttenhefner and Klug 2025).

Statistical analyses

We used linear models (LM) to evaluate the relationship between a suite of relevant covariates including flock characteristics (i.e. flock size, launch distance [distance between launch site and the flock], and initial habitat location [cattail or sunflower]), environmental conditions (i.e. wind speed, temperature, ambient light, Julian day, and time of day), and landscape (i.e. size of the sunflower–cattail complexes and proportion cattail; Fig. 1) per trial to model FID. We included the same variables in the arcsine-transformed percentage flock reduction model, and included flight path, (i.e. chaotic or herding), but not launch distance. If flock size increased, we considered it a 0% flock reduction. Although FID varies with launch distance (i.e. starting distance; Blumstein 2003), we did not use a standardized distance because of varied site logistics (e.g. land access, road locations, topography, and other obstacles). Thus, we included the launch distance in the FID model.

We used generalized linear models (GLM) to model the probability of a flock taking flight when the drone was within 80 m (logit link, binomial distribution, 0 = took flight when drone was ≤80 m, 1 = took flight when drone was >80 m) and probability of a flock abandoning the initial habitat location (0 = remained, 1 = abandoned) during hazing. We did not consider partial abandonment a success. We considered flock characteristics (i.e. flock size and initial habitat location [cattail or sunflower]), environmental conditions (i.e. wind speed, temperature, ambient light, Julian day, and time of day), and landscape (size of the sunflower–cattail complex and proportion cattail) per trial as covariates to model the probability of a flock taking flight when the drone was within the potential spraying distance (≤80 m) and probability of blackbirds abandoning the habitat where initially located. We also included flight path, (i.e. chaotic or herding) in the abandonment model.

We used the protocol outlined by Zuur et al. (2009) to apply systematic data exploration and assess model assumptions for the linear and generalized linear models. We began this process by assessing collinearity of continuous variables by using Spearman correlation coefficients, removing variables with a | r | ≥ 0.6. We dropped temperature from the FID linear model because of collinearity with Julian day (| r | = 0.64) and ambient light because of collinearity with time of day (| r | = 0.64). We dropped ambient light from the abandonment GLM because of collinearity with time of day (| r | = 0.76). We dropped ambient light from the percentage flock reduction linear model because of collinearity with time of day (| r | = 0.76). Because of the exploratory nature of this analysis, we selected optimal models by dropping explanatory variables one by one, by using a stepwise backwards selection based on Akaike’s information criterion (AIC; Table 1; Zuur et al. 2009). We evaluated the optimal model by using ΔAIC and selected the model with a score of 0.00. We retained variables of interest (e.g. drone flight path or habitat) even if they were not included in the optimal model. We applied model validation as outlined by Zuur et al. (2009) and evaluated optimal models to determine the effect of each variable (Table 2). We used Cook’s distance to identify overly influential observations but did not find any instances where Cook’s D score was >1 or altered the outcome of our optimal models. Measurements of distance and flock size were log transformed but results did not differ, so we report untransformed data. Finally, we assessed normality and homogeneity by plotting the residuals versus fitted models. We conducted all statistical analyses using RStudio software (ver. 4.3.1; RStudio Team 2020).

| Models | ΔAIC | K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized linear model – flight ≤80 m of approaching drone | |||

| H + JD + T + FS + C + W + TD + AL + SC | 12.78 | 10 | |

| H + JD + T + FS + C + W + TD + AL | 10.78 | 9 | |

| H + JD + T + FS + C + W + TD | 8.81 | 8 | |

| H + JD + T + FS + C + W | 6.87 | 7 | |

| H + JD + T + FS + C | 5.07 | 6 | |

| H + JD + T + FS | 3.40 | 5 | |

| H + JD + T | 1.93 | 4 | |

| H + JD | 0.54 | 3 | |

| H | 0.00 | 2 | |

| Linear model – flight initiation distance | |||

| TD + FS + LD + JD + H + C + SC + W | 7.83 | 10 | |

| TD + FS + LD + JD + H + C + SC | 5.86 | 9 | |

| TD + FS + LD + JD + H + C | 3.96 | 8 | |

| TD + FS + LD + JD + H | 2.44 | 7 | |

| TD + FS + LD + JD | 4.79 | 6 | |

| TD + FS + LD | 0.00 | 5 | |

| Generalized linear model – field abandonment | |||

| TD + FS + T + W + SC + H + C + FP + JD | 7.56 | 10 | |

| TD + FS + T + W + SC + H + C + FP | 5.58 | 9 | |

| TD + FS + T + W + SC + H + C | 3.62 | 8 | |

| TD + FS + T + W + SC + H | 1.78 | 7 | |

| TD + FS + T + W + SC | 1.45 | 6 | |

| TD + FS + T + W | 1.01 | 5 | |

| TD + FS + T | 0.00 | 4 | |

| Linear model – % flock reduction (arcsine) | |||

| C + T + W + FS + JD + H + TD + SC + FP | 12.99 | 11 | |

| C + T + W + FS + JD + H + TD + SC | 11.01 | 10 | |

| C + T + W + FS + JD + H + TD | 9.03 | 9 | |

| C + T + W + FS + JD + H | 7.04 | 8 | |

| C + T + W + FS + JD | 5.21 | 7 | |

| C + T + W + FS | 3.47 | 6 | |

| C + T + W | 2.17 | 5 | |

| C + T | 0.89 | 4 | |

| C | 0.00 | 3 | |

We applied a backwards selection based on Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) to arrive at optimal linear models (i.e. flight initiation distance [FID] and % flock reduction) and generalized linear models (i.e. probability of flocks taking flight within 80 m of an approaching drone [DJI Agras MG-1P] and flock abandonment of occupied habitat). Parameters are coded as follows: TD, time of day; FS, flock size; W, wind; T, temperature; AL, ambient light; SC, size of sunflower–cattail complex; C, proportion of cattail in complex; H, occupied habitat = cattail or sunflower; JD, (Julian day; LD, launch distance; and FP, flight path of drone = chaotic or herding. We dropped AL and T from the FID linear model, and AL from the flock reduction and field abandonment models because of collinearity. We included LD for the FID linear model. We added H to each optimal model and FP to field abandonment and flock reduction optimal models, given they were variables of interest.

| Parameter | Range | Mean | s.d. | Estimate | s.e. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Flight ≤80 m of approaching drone (n = 85) | |||||||

| Habitat (cattail or sunflower) | – | – | – | −2.177 | 0.78 | 0.005 | |

| (b) Flight initiation distance (n = 59) | |||||||

| Time of day | 7:30–17:45 | 11:07 | 2 h, 44 min | −2.077 | 0.69 | 0.004 | |

| Flock size | 40–6000 | 853 | 1370 | 0.004 | 1.45e−3 | 0.014 | |

| Launch distance (m) | 90–665 | 246 | 123 | −0.026 | 0.02 | 0.094 | |

| Habitat (cattail or sunflower) | – | – | – | −1.983 | 3.60 | 0.584 | |

| (c) Field abandonment (n = 60) | |||||||

| Time of day | 7:30–17:20 | 10:35 | 2 h, 33 min | 0.520 | 0.18 | 0.004 | |

| Flock size | 25–6000 | 960 | 1468 | −0.001 | 3.70e−4 | 0.005 | |

| Temperature (°C) | −3.0–28.4 | 10.4 | 6.6 | −0.089 | 0.05 | 0.099 | |

| Habitat (cattail or sunflower) | – | – | – | 0.639 | 0.68 | 0.344 | |

| Drone flight path (chaos or herding) | – | – | – | −0.041 | 0.65 | 0.949 | |

| (d) Percentage flock reduction (n = 60) | |||||||

| Cattail (proportion in field complex) | 0–1 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.602 | 0.41 | 0.150 | |

| Habitat (cattail or sunflower) | – | – | – | −0.021 | 0.17 | 0.898 | |

| Drone flight path (chaos or herding) | – | – | – | −0.012 | 0.15 | 0.935 | |

Results from (a) optimal generalized linear model for probability of flocks taking flight within 80 m of an approaching drone with spraying capabilities (0 = no, 1 = yes; DJI Agras MG-1P), (b) optimal linear model for flight initiation distance (FID ≤ 80 m, distance of potential spray drift) of flocks approached by the Agras, (c) optimal generalized linear model for probability of field abandonment by flocks, and (d) optimal linear model for percentage flock reduction (arcsine) in response to 10 min of hazing with the Agras. If the optimal model excluded variables of interest, such as drone flight path or habitat, they were retained because of research interest.

Results

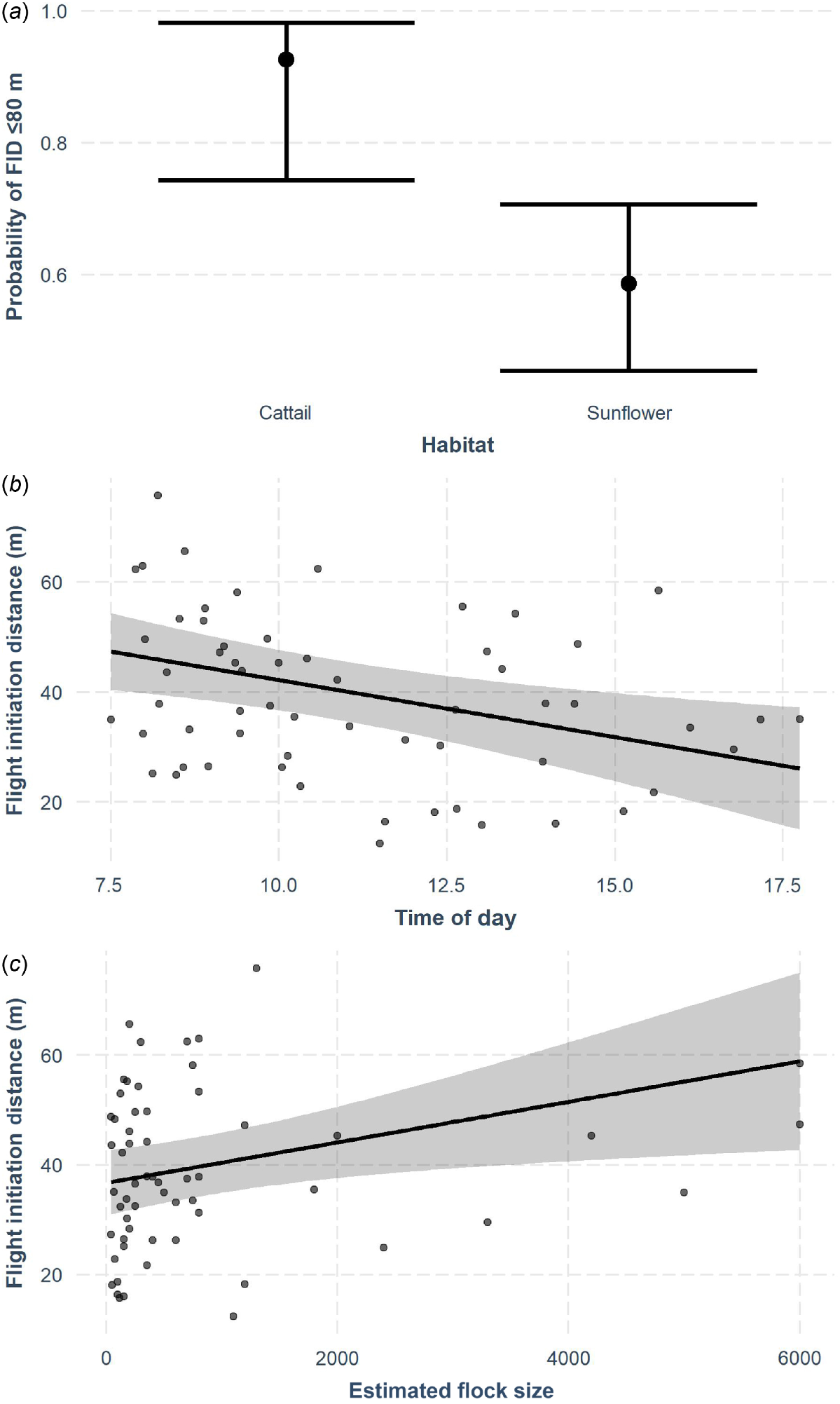

We approached 91 flocks (sunflower = 60, cattail = 31) to evaluate the probability of successful approach within the range of the potential spray drift (2019 = 31, 2020 = 60) and measured FID from the eye-in-the-sky drone video for 62 trials (2019 = 21, 2020 = 41) because of flocks taking flight beyond the potential spray drift (80 m) and sometimes outside of the field of view of the eye-in-the-sky. Of those 62 trials, we approached 36 flocks in sunflower and 26 in cattail adjacent to or within the sunflower field. The optimal model for probability of close approach (drone approached flock within 80 m) included habitat only (Tables 1, 2a, Fig. 3a). When we were able to closely approach flocks (≤80 m), average FID was 40 m ± 14.3 s.d. We combined years because we found no difference (t60 = 0.10, P = 0.92) between FID in 2019 (39 m ± 2.2 s.e.) and 2020 (39 m ± 2.5 s.e.). The optimal model for FID included time of day, flock size, and distance to launch (Tables 1, 2b, Fig. 3b, c). When the Agras was able to closely approach the flock (≤80 m), we found that FID was shorter with smaller flocks, later in the day (Table 2b, Fig. 3b, c).

Results of trials using a drone with spraying capabilities (DJI Agras MG-1P) from 4 September to 25 October (2019–2020) in sunflower–cattail complexes where sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was being actively damaged by mixed-species flocks of blackbirds (Icteridae) in North Dakota, USA. Cattail (Typha spp.) is used as daytime roosting habitat by blackbirds. (a) The probability of flocks taking flight within 80 m of the approaching Agras when located in cattail or sunflower. Model-based estimates of flight initiation distance (FID) for flocks responding to the approach of the Agras as a function of (b) time of day and (c) flock size. We held other model covariates at mean values. The shaded area shows 95% confidence intervals.

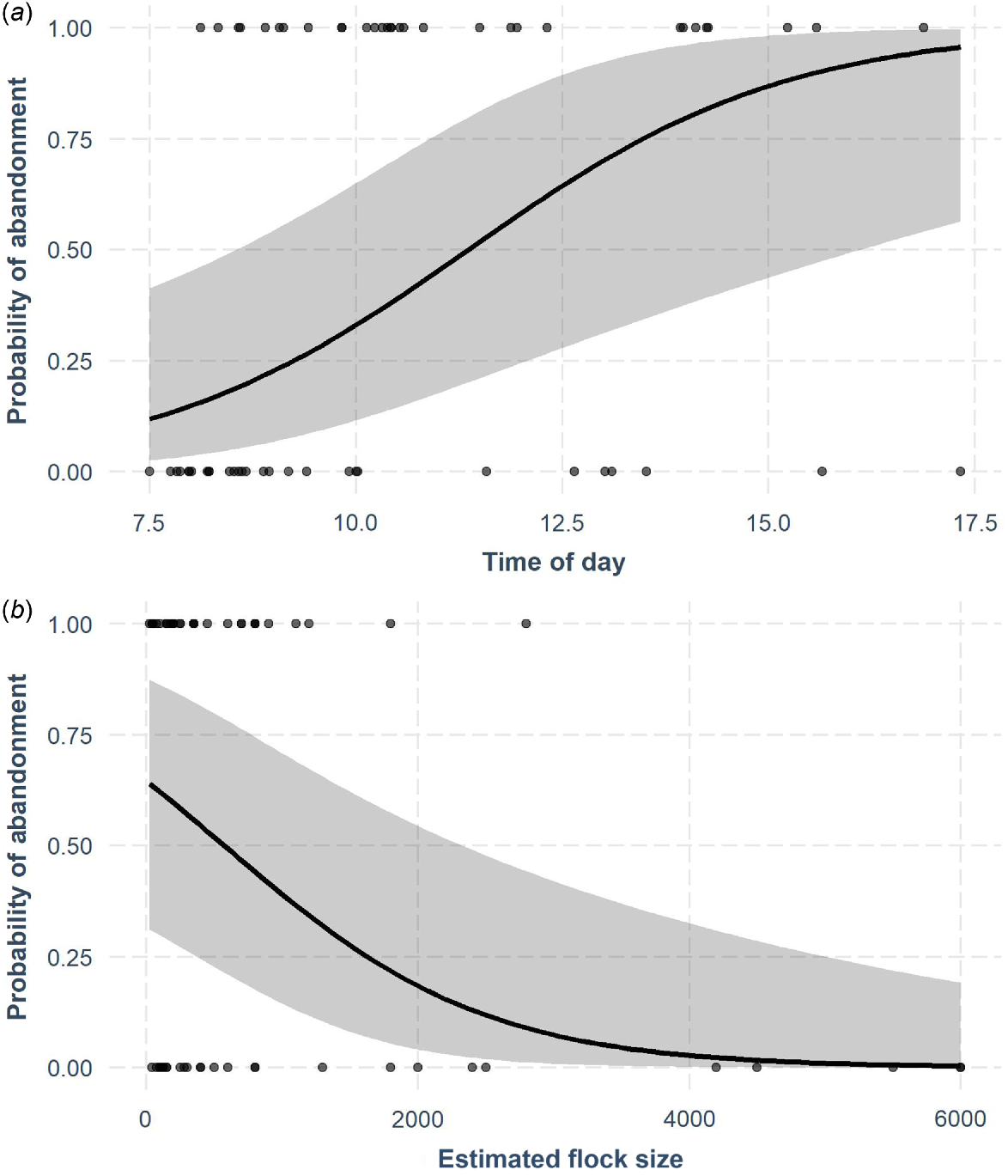

We conducted 60 hazing trials in 2020 (chaotic = 30 flocks, herding = 30 flocks) with 36 flocks being initially located in sunflower and 24 flocks in cattail within or adjacent to the sunflower field. Hazing trials resulted in 52% of flocks abandoning the targeted habitat within the 10-min hazing period (n = 31), whereas 37% of the flocks partially abandoned (n = 22), and 12% remained (n = 7). During the post-hazing period, 81% of flocks that completely abandoned during the hazing period returned to the same habitat (n = 25). The optimal model for abandonment included time of day, flock size, and temperature (Tables 1, 2c, Fig. 4). The probability of flock abandonment early in the morning was ~12% and increased as the day progressed (Fig. 4a), whereas the probability of abandonment for small flocks started at 65%, and decreased as flock size increased (Fig. 4b).

Results of drone hazing trials from 4 September to 25 October 2020 in sunflower–cattail complexes where sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was being actively damaged by mixed-species flocks of blackbirds (Icteridae) in North Dakota, USA. Cattail (Typha spp.) is used as daytime roosting habitat by blackbirds. The probability of flocks abandoning the starting habitat (i.e. sunflower or cattails) after 10 min of drone hazing as a function of (a) time of day and (b) flock size. We held other model covariates at mean values. The shaded area shows 95% confidence intervals.

Flock size increased (n = 14), stayed the same (n = 9), and decreased (n = 37; 100% decline: n = 6) in response to hazing. Excluding instances where flock size increased, flocks were, on average, reduced by 50% ± 36.8 s.d. (n = 46). We get an average reduction of 38% ± 38.6 s.d. (n = 60) if we include flock size increases as 0% declines. If we include instances where flock sizes increased (e.g. 40–600 birds is a 1400% increase), the average change was a 13% ± 2.2 s.d. (n = 60) increase in birds. Thus, when evaluating percentage decline, we included flock size increases as 0% declines to bound the percentage decline between 0 and 100% and arcsine transforming the response variable. Excluding flock size increases, flocks hazed in cattail (n = 21) were reduced by 49% ± 36.6 s.d., whereas flocks in sunflower (n = 25) were reduced by 51% ± 37.7 s.d. Flocks were reduced by 53% ± 38.7 s.d. when operating the drone with a chaotic path (n = 22), whereas a herding path (n = 24) reduced flocks by 47% ± 35.6 s.d. The optimal model for flock reduction included a positive relationship with proportion of cattail (Tables 1, 2d).

Discussion

Flock perceptions of risk appeared highest in the morning (i.e. larger FIDs earlier in the day), but the probability of abandonment from hazing increased as the day progressed, likely owing to energetic needs being met and birds moving to night-time roosting locations. Teräväinen (2022) found that graylag geese (Anser anser) were more likely to move to wetlands when scared out of crop fields in the morning and speculated that it was because of the beginning of mid-day loafing. Foraging by blackbirds also peaks in the morning and declines throughout the afternoon (Hintz and Dyer 1970). Although blackbirds are harder to move in the morning, the integration of spraying with hazing should be tested in the morning to understand the impact of the additional negative stimulus for successful hazing, especially on large flocks.

We also saw that larger flocks responded to the approaching drone sooner, but probability of abandonment was reduced with larger flocks, likely owing to increased vigilance combined with safety in numbers and how birds in large flocks collectively behave to avoid predation. Overall, 10 min of hazing by the Agras resulted in 52% of flocks abandoning the hazed area. However, 81% of flocks returned within 15 min post-hazing. This propensity to return to a resource has been seen in other studies attempting to disperse birds, including gulls from rooftops (Pfeiffer et al. 2023), vultures from landfills (Pfeiffer et al. 2021), and graylag geese from crop fields (Teräväinen 2022). It is likely that the limited alternative habitat (i.e. productive foraging areas ≥ sunflower fields) within a reasonable distance contributed to the high rate of return, a prediction illustrated by Gill et al. (2001) when discussing the ability of species to avoid disturbance. Pfeiffer et al. (2021) found that latency to return was negatively correlated with drone speed for turkey vultures and attributed it to slower drones spending more time in the area, increasing exposure time. Exposure time, resulting from greater launch distances, influences escape behavior (>FIDs) of blackbirds foraging in sunflower fields (Egan et al. 2023) and waterbirds on wetlands (Ryckman et al. 2022). Greater launch distances also affect the ability to aggressively maneuver a hazing drone across large fields and limits the ability to accurately observe flocks (Duttenhefner et al. 2024).

Flight initiation distance in flocks is the response of the birds located on the nearest edge of the flock seeking safety and moving towards the center of the flock (Ballerini et al. 2008). The collective movement of birds on the outer edge towards the center is an antipredator strategy that results in murmurations (Sumpter 2010). Flock size influenced when the flock took flight, and larger flocks flushed earlier to the approaching drone. Sociability within wildlife aggregations have been shown to influence flight distances of guanacos (Lama guanicoe; Schroeder and Panebianco 2021). Our study also supports research showing larger flock sizes have an earlier response time, because more eyes are watching for threats (Lima and Dill 1990; Jarrett et al. 2020; Egan et al. 2023). Flock size is known to affect perceptions of safety (Cooper and Blumstein 2015). Although larger flocks may attract more raptors, the likelihood of an individual being attacked is reduced in large flocks (Cresswell 1994).

Although the individual risk of predation is reduced in larger flocks, that risk could still be highest at certain times of day when predators are also in search of food (Lima and Dill 1990). Blackbird flocks took flight sooner in response to an approaching drone earlier in the day. We observed blackbird flocks refusing to abandon locations early in the morning, and the probability of abandonment increasing throughout the day. When flocks are initiating feeding early in the morning and a threat approaches, it creates a critical foraging decision, i.e. either remain at the valuable food source or leave and travel to another location with an unknown outcome (Abdulwahab et al. 2019). The agricultural landscape of this study, large monoculture fields, does not provide abundant alternative refugia or food resources (Whittingham and Evans 2004), which may have led birds to decide that the drone was not a sufficient threat to cause field abandonment. The probability of abandonment increased later in the afternoon, which is after most damage had occurred, owing to avian foraging occurring in the morning, and birds likely being on their way to night-time roosts in the late afternoon (Hintz and Dyer 1970). Future drone research should target flocks in the morning, to determine the best methods to reduce damage during an important feeding window when flocks are committed to the location.

Drone hazing has an immediate short-term impact on bird behavior as evidenced by reduced flock sizes. Wang et al. (2019) also found that flock activity was reduced immediately following drone hazing of silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis) in an Australian vineyard; however, the birds were hunkered down in the vines and did not necessarily abandon the area. Bhusal et al. (2018) reported reduced flock sizes as a result of drone hazing and increased flock sizes on days where no hazing took place. Reduced activity does not necessarily mean that the birds are not present in the hazed area during the observation period, but instead are likely to be less mobile immediately after drone hazing. Thus, a reduction in activity does not necessarily correlate to a reduction in crop damage. Depending on the crop, disturbing a flock could cause them to target different plants within a field, creating more damage. For example, any damage to sweet corn kernels affects the sale of the whole cob; thus, a hazing strategy that limits damage and the number of plants affected would be necessary (Carlson et al. 2013). Comparing flock activity before and after drone exposure or comparing flock behavior in response to a natural predator versus a drone would provide foundational understanding of how drones affect behavior (Duttenhefner 2023).

We did not find that wind speed or Julian day affected flock behavioral responses. Ambient light was highly correlated with time of day and dropped from most models; thus, ambient light may have also contributed to a flock’s ability to detect a threat, affecting FID and abandonment. The drone was not flown in wind speeds higher than 7 m s−1, which limited effects on drone speed and birds did not experience wind speeds that would have impeded flock movements. Wind speed may become more important when repellents are integrated on the hazing drone, given the impact on chemical spray drift. If we had not maintained a fairly constant drone speed, we likely would have seen shorter FIDs with an increased drone velocity similar to other mix-species bird flocks (Wilson et al. 2023). Julian day may not be impactful because of extreme climatological variation in the northern Great Plains during the trials, where direct weather measurements may be more informative.

Habitat can also have an impact on vigilance and alert to predators (Devereux et al. 2008; Jarrett et al. 2020). Studies evaluating FID have often looked at responses in open areas and distance to refugia habitat, such as nearby trees (Cooper and Blumstein 2015). Although birds can hide in both cattails and sunflower, cattails have denser leaf vegetation that could delay blackbird reactions by either reducing visibility or perceived risk, explaining why the drone could get closer to birds in cattail (Metcalfe 1984; Rodriguez-Prieto et al. 2008). Birds may perceive cattail as safer than sunflower, but detection of drones may also be delayed when birds are perched lower in the vegetation and occupying lower-lying parts of the field where cattail marshes are located. Although not statistically significant, flock reductions increased with the proportion of cattail, indicating that blackbirds were either harder to monitor in cattail or flocks sought refuge outside of the field complex on landscapes with abundant cattail. Avian repellents (e.g. methyl anthranilate) are applied to sunflower and not to areas with surface water. Although, we were able to closely approach flocks in cattail, future operations would need to cease spraying while moving birds out of cattail that is interspersed with sunflower.

Overall, 10 min of drone hazing in large sunflower fields was not likely to be sufficient to reduce crop damage, and future research should evaluate additional negative stimuli or the degree of continual hazing that is needed within a field to reduce yield loss. Smaller flocks are easier to move from a sunflower field, which highlights the importance of hazing early in the season prior to the formation of large flocks. Thus, early-season hazing, prior to sunflower maturity, may be beneficial to prevent establishment of foraging locations (Besser et al. 1979). Simultaneous damage estimates would benefit drone-hazing trials, because direct comparisons of tool efficacy would be possible. Drones are capable of aerially estimating damage in some scenarios (Barnas et al. 2019; Friesenhahn et al. 2023), but the structure of sunflower requires ground estimations of damage (Kaiser et al. 2021). Future research should evaluate increasing the duration or frequency of hazing, targeting the same fields over an entire season, or adding a negative stimulus, such as an avian repellent. If using a drone to apply an avian repellent, protocols should consider time of day, flock size, and habitat, but choice of flight path should mainly be concerned with optimizing spray drift to reach foraging blackbirds. There is promise for drone hazing in commercial agriculture, and additional research can use this study for a foundational understanding of the behavioral responses of blackbird flocks toward drones.

Data availability

Data and R Code are available upon request and are publicly available within US Forest Service’s Research Data Archive (White et al. 2024; https://doi.org/10.2737/NWRC-RDS-2024-006).

Declaration of funding

The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center (USDA-APHIS-WS-NWRC; 7438-0020-CA) and The National Sunflower Association (Project #20-P03) funded this research.

Acknowledgements

This paper forms part of the MS thesis of Mallory G. White (2021). We thank A. Schumacher, I. Carbajal, B. Clark, and M. Donaldson for fieldwork and assistance in data collection. We sincerely thank the farmers that gave us access to their sunflower fields. The North Dakota State University, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, #A20011), North Dakota Game and Fish Department (#GNF05044707, #GNF05151858), and the United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center (QA-3108) approved all data collection protocols. Drones were registered under the United States Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration (DJI Agras MG-1P, FA3E9WHATX; Phantom 4 Pro, FA37C3WEER; Mavic Air II, FA3PRTHX77) and flown under a Remote Pilot Certificate Part 107 (No. 4263743). Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purpose only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Government.

References

Abdulwahab UA, Osinubi ST, Abalaka J (2019) Risk of predation: A critical force driving habitat quality perception and foraging behavior of granivorous birds in a Nigerian forest reserve. Avian Research 10, 33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ampatzidis Y, Ward J, Samara O (2015) Autonomous system for pest bird control in specialty crops using unmanned aerial vehicles. In ‘Annual International Meeting, American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers’, ASABE Paper No. 152181748. (ASABE: St. Joseph, MI, USA). Available at https://doi.org/10.13031/aim.20152181748

Ballerini M, Cabibbo N, Candelier R, Cavagna A, Cisbani E, Giardina I, Orlandi A, Parisi G, Procaccini A, Viale M, Zdravkovic V (2008) Empirical investigation of starling flocks: A benchmark study in collective animal behaviour. Animal Behaviour 76, 201-215.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bansal S, Lishawa SC, Newman S, Tangen BA, Wilcox D, Albert D, Anteau MJ, Chimney MJ, Cressey RL, DeKeyser E, Elgersma KJ, Finkelstein SA, Freeland J, Grosshans R, Klug PE, Larkin DJ, Lawrence BA, Linz G, Marburger J, Noe G, Otto C, Reo N, Richards J, Richardson C, Rodgers L, Schrank AJ, Svedarsky D, Travis S, Tuchman N, Windham-Myers L (2019) Typha (cattail) invasion in North American wetlands: Biology, regional problems, impacts, ecosystem services, and management. Wetlands 39, 645-684.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barnas AF, Darby BJ, Vandeberg GS, Rockwell RF, Ellis-Felege SN (2019) A comparison of drone imagery and ground-based methods for estimating the extent of habitat destruction by lesser snow geese (Anser caerulescens caerulescens) in La Pérouse Bay. PLoS ONE 14, e0217049.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Besser JF, Berg WJ, Knittle CE (1979) Late-summer feeding patterns of red-winged blackbirds in a sunflower-growing area of North Dakota. In ‘Bird control seminars proceedings’. (Ed. WB Jackson) pp. 209–214. (Bowling Green University: Bowling Green, Ohio, USA). Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmbirdcontrol/27.

Bhusal S, Khanal K, Karkee M, Steensma KM, Taylor ME (2018) Unmanned aerial systems (UAS) for mitigating bird damage in wine grapes. In ‘Proceedings of the 14th international conference on precision agriculture’, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. (International Society of Precision Agriculture: Monticello, IL, USA)

Blumstein DT (2003) Flight-initiation distance in birds is dependent on intruder starting distance. The Journal of Wildlife Management 67, 852-857.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Burr PC, Samiappan S, Hathcock LA, Moorhead RJ, Dorr BS (2019) Estimating waterbird abundance on catfish aquaculture ponds using an unmanned aerial system. Human–Wildlife Interactions 13, 317-330 Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2302.

| Google Scholar |

Carlson JC, Tupper SK, Werner SJ, Pettit SE, Santer MM, Linz GM (2013) Laboratory efficacy of an anthraquinone-based repellent for reducing bird damage to ripening corn. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 145, 26-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chilvers BL (2024) Techniques for hazing and deterring birds during an oil spill. Marine Pollution Bulletin 201, 116276.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clark BA, Klug PE, Stepanian PM, Kelly JF (2020) Using bioenergetics and radar-derived bird abundance to assess the impact of a blackbird roost on seasonal sunflower damage. Human-Wildlife Interactions 14, 427-441.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cresswell W (1994) Flocking is an effective anti-predation strategy in redshanks, Tringa totanus. Animal Behaviour 47, 433-442.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DeLiberto ST, Werner SJ (2024) Applications of chemical bird repellents for crop and resource protection: A review and synthesis. Wildlife Research 51, WR23062.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Devereux CL, Fernández-Juricic E, Krebs JR, Whittingham MJ (2008) Habitat affects escape behaviour and alarm calling in common starlings Sturnus vulgaris. Ibis 150, 191-198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dolbeer RA (1990) Ornithology and integrated pest management: red-winged blackbirds Agelaius phoeniceus and corn. Ibis 132, 309-322.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dolbeer RA, Linz GM (2016) ‘Blackbirds.’ Wildlife damage management technical series. (US Department of Agriculture, Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services: Fort Collin, CO, USA). Available at http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrcwdmts/1

Duttenhefner JL, Klug PE (2024) Effective range of auditory frightening devices based on hearing capabilities and antipredator responses of nuisance blackbirds. Wildlife Society Bulletin 48, e1549.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Duttenhefner JL, Klug PE (2025) Observer estimation accuracy from drone-based imagery influenced by size of blackbird flocks foraging in sunflower. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Duttenhefner JL, Greives TJ, Klug PE (2024) Spraying drones: Efficacy of integrating an avian repellent with drone hazing to elicit blackbird flock dispersal and abandonment of sunflower fields. Wildlife Biology 2024, e01333.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Egan CC, Blackwell BF, Fernández-Juricic E, Klug PE (2020) Testing a key assumption of using drones as frightening devices: Do birds perceive drones as risky? The Condor 122, duaa014.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Egan CC, Blackwell BF, Fernández-Juricic E, Klug PE (2023) Dispersal of blackbird flocks from sunflower fields: Efficacy influenced by flock and field size but not drone platform. Wildlife Society Bulletin 47, e1478.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ernst K, Elser J, Linz G, Kandel H, Holderieath J, DeGroot S, Shwiff S, Shwiff S (2019) The economic impacts of blackbird (Icteridae) damage to sunflower in the USA. Pest Management Science 75, 2910-2915.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fernández-Juricic E, Jimenez MD, Lucas E (2002) Factors affecting intra- and inter-specific variations in the difference between alert distances and flight distances for birds in forested habitats. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80, 1212-1220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fernández-Juricic E, Deisher M, Stark AC, Randolet J (2012) Predator detection is limited in microhabitats with high light intensity: An experiment with brown-headed cowbirds. Ethology 118, 341-350.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forcey GM, Thogmartin WE, Linz GM, Mckann PC, Crimmins SM (2015) Spatially explicit modeling of blackbird abundance in the Prairie Pothole Region. The Journal of Wildlife Management 79, 1022-1033.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Friesenhahn BA, Massey LD, DeYoung RW, Cherry MJ, Fischer JW, Snow NP, VerCauteren KC, Perotto-Baldivieso HL (2023) Using drones to detect and quantify wild pig damage and yield loss in corn fields throughout plant growth stages. Wildlife Society Bulletin 47, e1437.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gill JA, Norris K, Sutherland WJ (2001) Why behavioural responses may not reflect the population consequences of human disturbance. Biological Conservation 97, 265-268.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hahn N, Mwakatobe A, Konuche J, de Souza N, Keyyu J, Goss M, Chang’a A, Palminteri S, Dinerstein E, Olson D (2017) Unmanned aerial vehicles mitigate human–elephant conflict on the borders of Tanzanian Parks: A case study. Oryx 51, 513-516.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hintz JV, Dyer MI (1970) Daily rhythm and seasonal change in the summer diet of adult red-winged blackbirds. The Journal of Wildlife Management 34, 789-799.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jarrett D, Calladine J, Cotton A, Wilson MW, Humphreys E (2020) Behavioural responses of non-breeding waterbirds to drone approach are associated with flock size and habitat. Bird Study 67, 190-196.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kaiser BA, Johnson BL, Ostlie MH, Werner SJ, Klug PE (2021) Inefficiency of anthraquinone-based avian repellents when applied to sunflower: The importance of crop vegetative and floral characteristics in field applications. Pest Management Science 77, 1502-1511.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Klosterman ME, Linz GM, Slowik AA, Homan HJ (2013) Comparisons between blackbird damage to corn and sunflower in North Dakota. Crop Protection 53, 1-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Klug PE, Shiels AB, Kluever BM, Anderson CJ, Hess SC, Ruell EW, Bukoski WP, Siers SR (2023) A review of nonlethal and lethal control tools for managing the damage of invasive birds to human assets and economic activities. Management of Biological Invasions 14, 1-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Laursen K, Kahlert J, Frikke J (2005) Factors affecting escape distances of staging waterbirds. Wildlife Biology 11, 13-19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lima SL, Dill LM (1990) Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: A review and prospectus. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68, 619-640.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Linz GM, Knittle CE, Cummings JL, Davis JE, Jr., Otis DL, Bergman DL (1991) Using aerial marking for assessing population dynamics of late summer roosting red-winged blackbirds. Prairie Naturalist 23, 117-126.

| Google Scholar |

Linz GM, Sawin RS, Lutman MW, Homan HJ, Penry LB, Bleier WJ (2003) Characteristics of spring and fall blackbird roosts in the northern Great Plains. In ‘Proceedings of the 10th wildlife damage management conference’. (Eds KA Fagerstone, GW Witmer) pp. 220–228 (USDA National Wildlife Research Center: Hot Springs, AR, USA). Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/242

Lunn RB, Blackwell BF, DeVault TL, Fernández-Juricic E (2022) Can we use antipredator behavior theory to predict wildlife responses to high-speed vehicles? PLoS ONE 17, e0267774.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Metcalfe NB (1984) The effects of habitat on the vigilance of shorebirds: is visibility important? Animal Behaviour 32, 981-985.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mohamed WMW, Naim MNM, Abdullah A (2020) The efficacy of visual and auditory bird scaring techniques using drone at paddy fields. In ‘IOP conference series: materials science and engineering’. p. 012072. (IOP Publishing). Available at https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/834/1/012072

Paranjape AA, Chung S-J, Kim K, Shim DH (2018) Robotic herding of a flock of birds using an unmanned aerial vehicle. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 34, 901-915.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Penny SG, White RL, Scott DM, MacTavish L, Pernetta AP (2019) Using drones and sirens to elicit avoidance behaviour in white rhinoceros as an anti-poaching tactic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286, 20191135.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pfeiffer MB, Blackwell BF, Seamans TW, Buckingham BN, Hoblet JL, Baumhardt PE, DeVault TL, Fernández-Juricic E (2021) Responses of turkey vultures to unmanned aircraft systems vary by platform. Scientific Reports 11, 21655.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pfeiffer MB, Pullins CK, Beckerman SF, Hoblet JL, Blackwell BF (2023) Investigating nocturnal UAS treatments in an applied context to prevent gulls from nesting on rooftops. Wildlife Society Bulletin 47, e1423.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rhoades CA, Allen PJ, King DT (2019) Using unmanned aerial vehicles for bird harassment on fish ponds. In ‘Proceedings of the 18th wildlife damage management conference’. (Eds JB Armstrong, GR Gallagher) pp. 13–23. (USDA National Wildlife Research Center: Starkville, MS, USA) Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2290

Rodriguez-Prieto I, Fernández-Juricic E, Martín J (2008) To run or to fly: Low cost versus low risk escape strategies in blackbirds. Behaviour 145, 1125-1138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rosenberg KV, Dokter AM, Blancher PJ, Sauer JR, Smith AC, Smith PA, Stanton JC, Panjabi A, Helft L, Parr M, Marra PP (2019) Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366, 120-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

RStudio Team (2020) RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA. Available at http://www.rstudio.com/

Ryckman MD, Kemink K, Felege CJ, Darby B, Vandeberg GS, Ellis-Felege SN (2022) Behavioral responses of blue-winged teal and northern shoveler to unmanned aerial vehicle surveys. PLoS ONE 17, e0262393.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sausse C, Baux A, Bertrand M, Bonnaud E, Canavelli S, Destrez A, Klug PE, Olivera L, Rodriguez E, Tellechea G, Zuil S (2021) Contemporary challenges and opportunities for the management of bird damage at field crop establishment. Crop Protection 148, 105736.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671-675.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schroeder NM, Panebianco A (2021) Sociability strongly affects the behavioural responses of wild guanacos to drones. Scientific Reports 11, 20901.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stonefish D, Eshleman MA, Linz GM, Jeffrey Homan H, Klug PE, Greives TJ, Gillam EH (2021) Migration routes and wintering areas of male Red-winged Blackbirds as determined using geolocators. Journal of Field Ornithology 92, 284-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vas E, Lescroël A, Duriez O, Boguszewski G, Grémillet D (2015) Approaching birds with drones: first experiments and ethical guidelines. Biology Letters 11, 20140754.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wandrie LJ, Klug PE, Clark ME (2019) Evaluation of two unmanned aircraft systems as tools for protecting crops from blackbird damage. Crop Protection 117, 15-19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wang Z, Griffin AS, Lucas A, Wong KC (2019) Psychological warfare in vineyard: using drones and bird psychology to control bird damage to wine grapes. Crop Protection 120, 163-170.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wang Z, Fahey D, Lucas A, Griffin AS, Chamitoff G, Wong KC (2020) Bird damage management in vineyards: Comparing efficacy of a bird psychology-incorporated unmanned aerial vehicle system with netting and visual scaring. Crop Protection 137, 105260.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Werner SJ, Homan HJ, Avery ML, Linz GM, Tillman EA, Slowik AA, Byrd RW, Primus TM, Goodall MJ (2005) Evaluation of Bird Shield™ as a blackbird repellent in ripening rice and sunflower fields. Wildlife Society Bulletin 33, 251-257.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Whittingham MJ, Evans KL (2004) The effects of habitat structure on predation risk of birds in agricultural landscapes. Ibis 146, 210-220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson JP, Amano T, Fuller RA (2023) Drone-induced flight initiation distances for shorebirds in mixed-species flocks. Journal of Applied Ecology 60, 1816-1827.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |